[Image: A rendering of the “Timeship” cryogenic facility by architect Stephen Valentine, via New Scientist].

The primary setting of Don DeLillo’s new novel, Zero K, is a cryogenic medical facility in the mountainous deserts of Central Asia. There we meet a family that is, in effect, freezing itself, one by one, for reawakening in a speculative second life, in some immortally self-continuous version of the future.

First the mother goes; then the father, far before his time, willfully and preemptively ending things out of loneliness; next would be the son, the book’s ostensible protagonist, if he didn’t arrive with so many reservations about the procedure. Either way, it’s a question of what it means to delay one thing while prolonging another—to preserve one state as a means of preventing another from setting in. One is a refusal to let go of something you already possess; the other is a refusal to accept something you don’t yet have. An addiction to comfort vs. a fear of the new.

Without getting into too many of the book’s admittedly sparse details, it suffices to say that Zero K continues many of DeLillo’s most consistent themes—finance (Cosmopolis), apocalyptic religion (Mao II), the symbolic allure of mathematical analysis (Ratner’s Star).

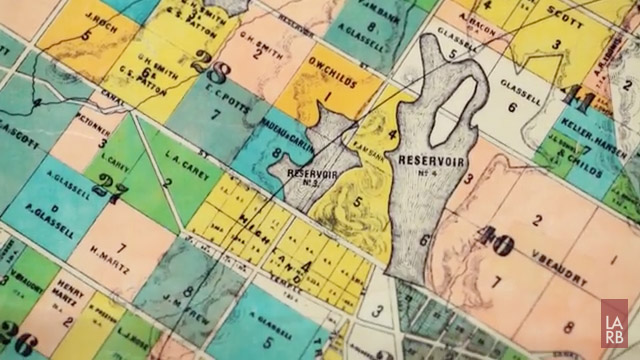

What makes the book worth a mention here are some of the odder details of this cryogenic compound. It is a monumental space, described with references both to grand scientific and medical facilities—think the Salk Institute, perhaps—as well as to postmodern religious centers, this desert megachurch of the secular afterlife.

Yet its strangest details come from the site’s peripheral ornamentation: there are artificial gardens, for example, filled with resin-based and plastic plant life, and there is a surreal distribution of lifeless mannequins throughout the grounds, standing in penitential silence amongst the fake greenery. Unliving, they cannot die.

These stylized representations of biology, or replicant life forms that come across more like mockery than mimicry, expand the novel’s central conceit of frozen life—life reduced to absolute stillness, placed on pause, in hibernation, in temporal limbo, preserved—out into the landscape itself. It is an obvious symbolism, which is one of the book’s shortcomings; these deathless gardens with their plastic guards remain creepily poetic, nonetheless. These can also be seen as fittingly cynical flourishes for a facility founded on loose talk of singularities, medical resurrection, and quote-unquote human consciousness, as if even the designers themselves were in on the joke.

Briefly, despite my lukewarm feelings about the actual novel, I should say that I really love the title, Zero K. It is, of course, a thermal description—or zero K, zero kelvin, absolute zero, cryogenic perfection. Yet it is also refers to an empty digital file—zero k, zero kb—or, perhaps more accurately, a file saved with nothing in it, thus seemingly a quiet authorial nod to the idea that absolutely nothing about these characters is being saved, or preserved, in their quest for immortality. And it is also a nicely cross-literary reference to Frank Kafka’s existential navigator of European political absurdity, Josef K. or just K. From Josef K. to Zero K, his postmodern replacement.

The title, then, is brilliant—and the mannequins and the plastic plant life found at an end-times cryogenic facility in Central Asia make for an amazing set-up—but it’s certainly not one of DeLillo’s strongest books. In fact, I have been joking to people that, if you really want to read a novel this summer written by an aging white male cultural figure known for his avant-garde aesthetics, consider picking up Consumed, David Cronenberg’s strange, possibly too-Ballardian novel about murder, 3D printing, North Korean kidnapping squads, and more, rather than Zero K (or, of course, read both).

In any case, believe it or not, this all came out of the fact that I was about to tweet a link to a long New Scientist article about a cryogenic facility under construction in Texas when I realized that I had more to say than just 140 characters (Twitter, I have found, is actually a competitor to your writing masquerading as an enabler of it—alas, something I consistently re-forget).

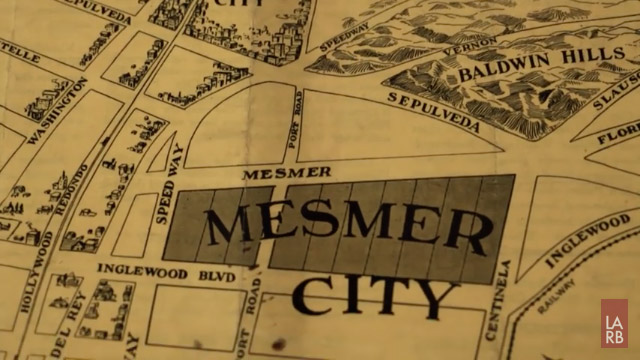

There, Helen Thompson takes us to a place called Comfort, Texas.

[Image: Rendering of the “Timeship” facility by architect Stephen Valentine].

“The scene from here is surreal,” Thompson writes. “A lake with a newly restored wooden gazebo sits empty, waiting to be filled. A pregnant zebra strolls across a nearby field. And out in the distance some men in cowboy hats are starting to clear a huge area of shrub land. Soon the first few bricks will be laid here, marking the start of a scientific endeavour like no other.” A “monolithic building” is under construction in Comfort, and it will soon be “the new Mecca of cryogenics.”

Called Timeship, the monolithic building will become the world’s largest structure devoted to cryopreservation, and will be home to thousands of people who are neither dead nor alive, frozen in time in the hope that one day technology will be able to bring them back to life. And last month, building work began.

The resulting facility will include “a building that would house research laboratories, DNA from near-extinct species, the world’s largest human organ biobank, and 50,000 cryogenically frozen bodies.”

The design of the compound is not free of the sort of symbolic details we saw in DeLillo’s novel. Indeed, Thompson explains, “Parts of the project are somewhat theatrical—backup liquid nitrogen storage tanks are covered overhead by a glass-floored plaza on which you can walk surrounded by a fine mist of clouds—others are purely functional, like the three wind turbines that will provide year-round back-up energy.” And then there’s that pregnant zebra.

[Image: An otherwise totally unrelated photo of a circuit, chosen simply for its visual resemblance to the mandala/temple/resurrection facility in Texas; via DARPA].

It’s a long feature, worth reading in full—so click over to New Scientist to check it out—but what captivates me here is the notion that a sufficiently advanced scientific facility could require an architectural design that leans more toward religious symbolism.

What are the criteria, in other words, by which an otherwise rational scientific undertaking—conquering death? achieving resurrection? simulating the birth of the universe?—can shade off into mysticism and poetry, into ritual and symbolism, into what Zero K refers to as “faith-based technology,” and what architectural forms are thus most appropriate for housing it?

In fact, DeLillo presents a political variation on this question in Zero K. At one point, the book’s narrator explains, looking out over the cryogenic facility, “I wondered if I was looking at the controlled future, men and women being subordinated, willingly or not, to some form of centralized command. Mannequined lives. Was this a facile logic? I thought about local matters, the disk on my wristband that tells [the facility’s administrators], in theory, where I am at all times. I thought about my room, small and tight but embodying an odd totalness. Other things here, the halls, the veers, the fabricated garden, the food units, the unidentifiable food, or when does utilitarian become totalitarian.” When does utilitarian become totalitarian.

When do scientific undertakings become religious movements? When does minimalism become a form of political control?

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of whales, courtesy Public Domain Review.]

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of whales, courtesy Public Domain Review.] [Image: Brainglass, via the

[Image: Brainglass, via the  [Image: Carbonized papyrii on display at

[Image: Carbonized papyrii on display at  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Chelly, courtesy Albin-Michel/

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Chelly, courtesy Albin-Michel/ [Image: Lincoln Cathedral, via

[Image: Lincoln Cathedral, via  [Image: The “former constellation”

[Image: The “former constellation”

[Images: Muons beneath the Alps;

[Images: Muons beneath the Alps;  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy  [Image: Screen grab from

[Image: Screen grab from  [Image: Screen grab from

[Image: Screen grab from  [Image: Screen grab from

[Image: Screen grab from  [Image: Screen grab from

[Image: Screen grab from

[Images: The sarcophagus of King Seti I; courtesy

[Images: The sarcophagus of King Seti I; courtesy

[Image: Screen grab from a

[Image: Screen grab from a  [Image: Screen grab from a

[Image: Screen grab from a  [Image: Screen grab from a

[Image: Screen grab from a  [Image: Screen grab from a

[Image: Screen grab from a  [Image: Smartphone shot in non-ideal lighting conditions].

[Image: Smartphone shot in non-ideal lighting conditions]. [Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the  [Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From