[Image: The “former constellation” Argo Navis, via Wikipedia].

[Image: The “former constellation” Argo Navis, via Wikipedia].

Taps mic… Is this thing still on…

1. Hidden Charms was a conference on “the magical protection of buildings,” organized by Brian Hoggard. The one-day symposium looked at everything from ritual “protection marks” to dead cats stored in glass jars, put there “to keep the witches away.”

2. Amazon wants to put robots in every home. “The retail and cloud computing giant has embarked on an ambitious, top-secret plan to build a domestic robot, according to people familiar with the plans. Codenamed ‘Vesta,’ after the Roman goddess of the hearth, home and family,” the robot “could be a sort of mobile Alexa,” Businessweek speculates, “accompanying customers in parts of their home where they don’t have Echo devices. Prototypes of the robots have advanced cameras and computer vision software and can navigate through homes like a self-driving car.”

3. A woman in Austin, Texas, went missing in 2015. Without monthly payments, her house was eventually seized and sold by the bank—but the home’s new owners found the skeletal remains of a body inside one of the walls back in March. It was the missing woman. “In the attic, there was a broken board that led down to the space” where the skeleton was found, a coroner’s spokesperson explained. “Law enforcement thinks she may have been up in the attic and fell through the attic floor.” Horrifically, whether she was killed by the fall or remained alive, trapped inside the wall, is unclear.

4. At an event here in Los Angeles a few weeks ago, artist and writer Julia Christensen drew my attention to officially recognized “former constellations,” or named star groups that are no longer considered referentially viable.

5. The Roman monetary system left a planetary-archaeological trace in Greenland’s ice sheet, according to Rob Meyer of The Atlantic. “A team of archaeologists, historians, and climate scientists have constructed a history of Rome’s lead pollution,” Meyer explains, “which allows them to approximate Mediterranean economic activity from 1,100 b.c. to 800 a.d. They found it hiding thousands of miles from the Roman Forum: deep in the Greenland Ice Sheet, the enormous, miles-thick plate of ice that entombs the North Atlantic island.” With this data, they have “reconstructed year-by-year economic data documenting the rise and fall of the Roman Republic and Empire.” Oddly enough, this means the Greenland Ice Sheet is a landscape-scale archive of Roman financial data.

6. Speaking of economic data mined from indirect sources, “satellite imagery that tracks changes in the level of nighttime lighting within and between countries over time” might also reveal whether countries are lying about the strengths of their economies. According to researcher Luis R. Martinez, “increases in nighttime lighting generally track with increases in GDP,” and this becomes of interest when lighting levels don’t correspond with officially given numbers. Of course, this is not the first time that satellite imagery has been used to estimate economic data.

7. “Today our experience of the night differs significantly from that of our ancestors,” Nancy Gonlin and April Nowell write for Sapiens. “Before they mastered fire, early humans lived roughly half their lives in the dark.” Cue the rise of “archaeological inquiries into the night,” or what Gonlin and Nowell have evocatively named the “archaeology of night.”

8. There was an amazing article by Jake Halpern published in The New Yorker two years ago about Nazi gold fever in Poland and the incredible amount of amateur detective operations there dedicated to finding an alleged buried fortune. It’s a wild mix of abandoned WWII bunkers, secret underground cities in the forest, and urban legends of untold wealth. It turns out, however, there is a (vaguely) similar obsession with lost or buried gold in northwestern Pennsylvania: “For decades, treasure hunters in Pennsylvania have suspected that there is a trove of Civil War gold lost in a rural forest in the northwestern part of the state,” the New York Times reports. “The story of the gold bars was pieced together from old documents, a map and even a mysterious note found decades ago in a hiding place on the back of a bed post in Caledonia,” the paper explains.

9. People are drawn to forests for all sorts of reasons. As Alex Mar wrote last autumn for the Virginia Quarterly Review, the Slender Man phenomenon—that inspired two young girls to try to murder a classmate—also had a forest element. “Girls lured out into the dark woods—this is the stuff of folk tales from so many countries,” Mar writes, “a New World fear of the Puritans, an image at the heart of witchcraft and the occult, timeless.” Mar points out that, after the attempted murder, the two girls began heading “to Wisconsin’s Nicolet National Forest on foot, nearly 200 miles north. They were convinced that, once there, if they pushed farther and farther into the nearly 700,000-acre forest, they would find the mansion in which their monster [Slender Man] dwells and he would welcome them.” The whole article is an interesting look at childhood, folklore, and the sometimes dark allure of the wild.

10. More treasure hunts: is there a cache of buried armaments, stolen from a National Guard armory in 1970, hidden somewhere in Amesbury, Massachusetts? According to a commenter on the Cast Boolits forum, William Gilday, who once “led an assault on a National Guard armory in Newburyport” and who spent nearly half of his life in prison for killing a police officer, confessed on his death bed that he buried guns and ammunition stolen from the armory somewhere in his hometown of Amesbury. “It’s one of those ‘what if’ things,” the commenter continues. “I’ve known about the confession for years, and I walk my dog in the ‘suspected’ vicinity just about every day. The problem is that the ‘authorities’ claim that everything that was stolen was recovered. But, a few weeks ago, I emailed a local radio talk show host who was involved in the death bed confession and I asked her if she thought that stolen items really had been buried in my town and she replied, ‘Yes…do you know where they are?’”

11. “A dispute between Serbia and Kosovo has disrupted the electric power grid for most of the Continent, making certain kinds of clocks—many of those on ovens, in heating systems and on radios—run up to six minutes slow,” the New York Times reported back in March. “The fluctuation in the power supply is infinitesimally small—not nearly enough to make a meaningful difference for most powered devices—and if it were a brief disturbance, the effect on clocks might be too little to worry about.” But this six-minute lag is enough to cause subtle effects in people’s lives. A bad first novel could be written about slow clocks, distant political disputes, and some sort of disastrous event—a missed train, a skipped meeting—in the narrator’s personal life.

12. The above story reminds me of the suspicion last year that Russia was using some sort of large-scale GPS jamming device in the Black Sea. “Reports of satellite navigation problems in the Black Sea suggest that Russia may be testing a new system for spoofing GPS,” David Hambling reported for New Scientist. “This could be the first hint of a new form of electronic warfare available to everyone from rogue nation states to petty criminals.” The reason I say this is because you can easily imagine a scenario where someone is driving around, totally lost, receiving contradictory if not frankly nonsensical navigation instructions, and it’s because they are an unwitting, long-distance victim of geographic weaponry being used in a war zone far away.

13. The legendary music fest Sónar has been sending music to “a potentially habitable exoplanet” called GJ273b, attempting to contact alien intelligence with transmissions of electronic music. Transmission 1 was sent back in October; Transmission 2 ended today. The transmissions should arrive at the planet in November 2030.

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via  [Image: Stackin’ it at the

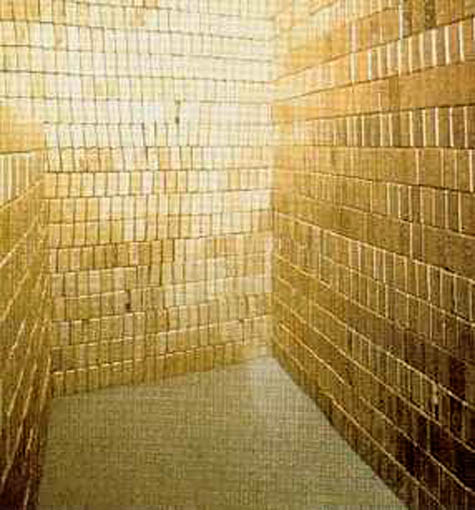

[Image: Stackin’ it at the  [Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at

[Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at

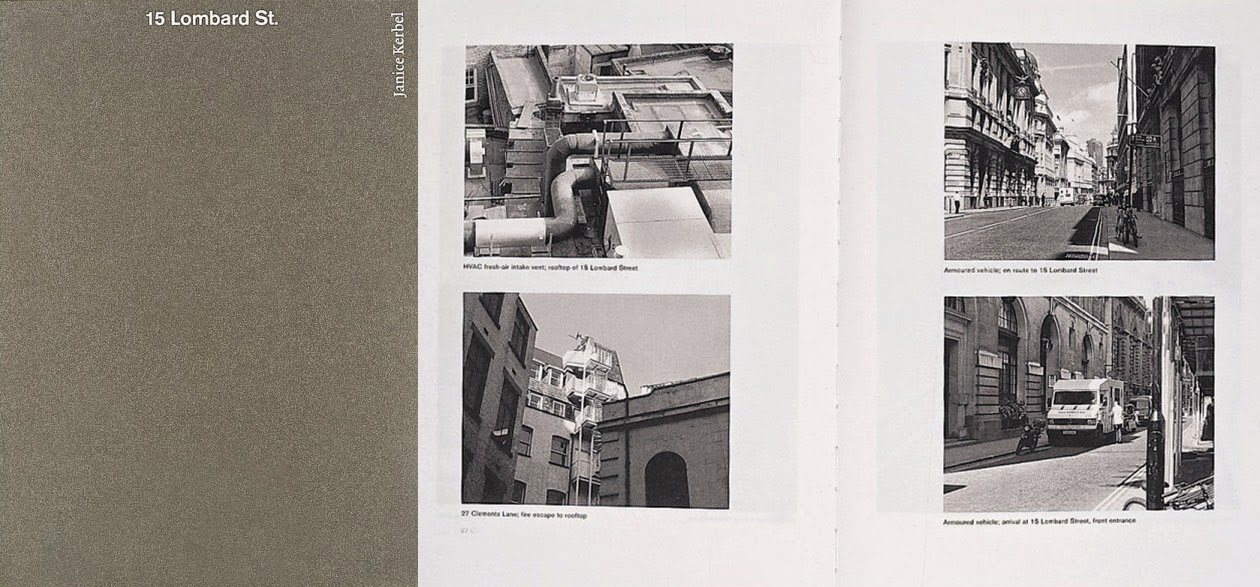

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: The cover and a spread from