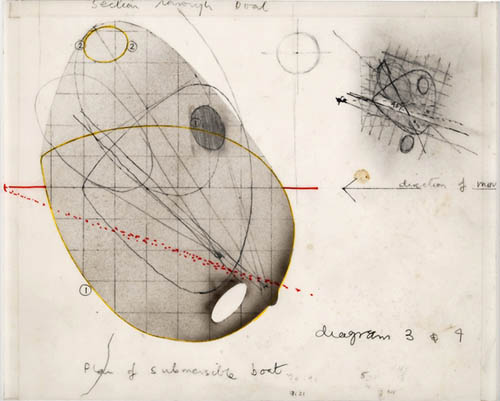

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal exploring the implications of cones of vision and their interaction with an existing neoclassical ‘temple’ on the River Thames in Henley, Berkshire,” by Archigram/Michael Webb].

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal exploring the implications of cones of vision and their interaction with an existing neoclassical ‘temple’ on the River Thames in Henley, Berkshire,” by Archigram/Michael Webb].

As of roughly 16 hours ago, the Archigram Archival Project is finally online and ready to for browsing, courtesy of the University of Westminster: the archive “makes the work of the seminal architectural group Archigram available free online for public viewing and academic study.”

The newly launched site includes more than 200 projects; “this comprises projects done by members before they met, the Archigram magazines (grouped together at no. 100), the projects done by Archigram as a group between 1961 and 1974, and some later projects.” There are also brief biographies of each participating member of the collaborative group: Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Michael Webb.

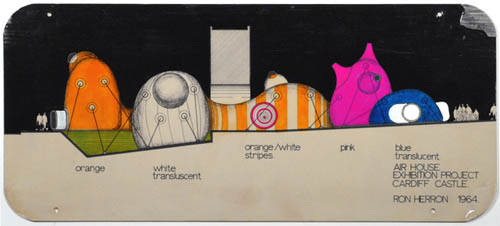

[Image: “Proposal for a series of inflatable dwellings as part of an exhibition for the Commonwealth Festival, located in the lodge of Cardiff Castle,” by Archigram/Ron Herron].

[Image: “Proposal for a series of inflatable dwellings as part of an exhibition for the Commonwealth Festival, located in the lodge of Cardiff Castle,” by Archigram/Ron Herron].

Even at their most surreal, it feels as if Archigram did, in fact, accurately foresee what the architectural world was coming to. After all, if Chalk & Co. had built the things around us, there would be electricity supplies in the middle of nowhere and drive-in housing amidst the sprawl; for good or for bad, we’d all be playing with gadgets like the Electronic Tomato, that perhaps would not have given the iPhone a run for its money but was a “mobile sensory stimulation device,” nonetheless. We might even live together on the outer fringes of “extreme suburbs,” constructed like concentric halos around minor airports, such as Peter Cook’s “Crater City,” an “earth sheltered hotel-type city around central park,” or “Hedgerow Village,” tiny clusters of houses like North Face tents “hidden in hedgerow strips.”

There would be temporary, inflatable additions to whole towns and cities; pyramidal diagrid megastructures squatting over dead neighborhoods like malls; dream cities like Rorschach blots stretched across the sky, toothed and angular Montreal Towers looming in the distance; plug-in universities and capsule homes in a computer-controlled city of automatic switches and micro-pneumatic infrastructure.

At its more bizarre, there would have been things like the Fabergram castle, as if the Teutonic Knights became an over-chimneyed race of factory-builders in an era of cheap LSD, reading Gormenghast in Disneyworld, or this proposal “for technology enabling underwater farming by scuba divers, including chambers, floats and tubes for walking and farm control.” After all, Archigram asked, why live in a house at all when you can live in a submarine? Why use airplanes when you can ride a magic carpet constructed from shining looms in a “‘reverse hovercraft’ facility where a body can be held at an adjustable point in space through the use of jets of air”?

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a kit of architectural parts for ‘tuning-up’ existing buildings, applied to an invented suburb,” by Archigram/Ron Herron].

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a kit of architectural parts for ‘tuning-up’ existing buildings, applied to an invented suburb,” by Archigram/Ron Herron].

It might not be architects who have realized much of this fever dream of the world to come, but that doesn’t mean that these ideas have not, in many cases, been constructed. Archigram spoke of instant cities and easily deployed, reconfigurable megastructures—but the people more likely to own and operate such spaces today are Big Box retailers, with their clip-on ornaments, infinitely exchangeable modular shelving, and fleeting themes-of-the-week. Archigram’s flexible, just-in-time, climate-controlled interiors are not a sign of impending utopia, in other words, but of the reach of your neighborhood shopping mall—and the people airdropping instant cities into the middle of nowhere today are less likely to be algorithmically trained Rhino enthusiasts from architecture school, but the logistics support teams behind Bechtel and the U.S. military.

Another way of saying this is that Archigram’s ideas seem unbuilt—even unbuildable—but those ideas actually lend themselves surprisingly well to the environment in which we now live, full of “extreme suburbs,” drive-in everything, KFC-supplied army bases in the middle of foreign deserts, robot bank tellers, and huge, HVAC-dependent wonderlands on the exurban fringe.

The irony, for me, is that Archigram’s ideas have, in many ways, actually been constructed—but in most cases it was for the wrong reasons, in the wrong ways, and by the wrong people.

[Image: Proposal “fusing alternative and changing Archigram structures, amenities and facilities with traditional and nostalgic structures,” by Archigram/Peter Cook].

[Image: Proposal “fusing alternative and changing Archigram structures, amenities and facilities with traditional and nostalgic structures,” by Archigram/Peter Cook].

In any case, what was it about Archigram that promised on-demand self-transformation in an urban strobe of flashing lights but then got so easily realized as a kind of down-market Times Square? How did Archigram simply become the plug-in units of discount retail—or the Fun Palaces of forty years ago downgraded to Barnes & Noble outlets in the suburbs? How did the Walking City become Bremer Walls and Forward Operating Bases, where the Instant City meets Camp Bondsteel?

Archigram predicted a modular future propelled by cheap fuel, petrodollars, and a billion easy tons of unrecycled plastic—but, beneath that seamless gleam of artificial surfacing and extraterrestrial color combinations was a fizzy-lifting drink of human ideas—as many ideas as you could think of, sometimes imperfectly illustrated but illustrated nonetheless, and, thus, now canonical—all of it wrapped up in a dossier of new forms of planetary civilization. Archigram wasn’t just out on the prowl for better escalators or to make our buildings look like giant orchids and Venus Flytraps, where today’s avant-bust software formalism has unfortunately so far been mired; it wasn’t just bigger bank towers and the Burj Dubai.

Instead, Archigram suggested, we could all act differently if we had the right spaces in which to meet, love, and live, and what matters to me less here is whether or not they were right, or even if they were the only people saying such things (they weren’t)—what matters to me is the idea that architecture can reframe and inspire whole new anthropologies, new ways of being human on earth, new chances to do something more fun tomorrow (and later today). Architecture can reshape how we inhabit continents, the planet, and the solar system at large. Whether or not you even want inflatable attics, flying carpets, and underwater eel farms, the overwhelming impulse here is that if you don’t like the world you’ve been dropped into, then you should build the one you want.

In any case, the entire Archigram Archival Project is worth a look; even treated simply as an historical resource, its presence corrects what had been a sorely missing feature of online architecture culture: we can now finally link to, and see, Archigram’s work.

(Note: Part of the latter half of this post includes some re-edited bits from a comment I posted several months ago).

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via  [Image: The mineral library, via

[Image: The mineral library, via  [Image: One of the pots; photo by

[Image: One of the pots; photo by  [Image: One of the pots; photo by

[Image: One of the pots; photo by  [Image: Photo by James DiLoreto/Smithsonian Institution, via the

[Image: Photo by James DiLoreto/Smithsonian Institution, via the  [Image: Behind the scenes of the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by

[Image: Behind the scenes of the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by  [Image: Amongst the fish of the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by

[Image: Amongst the fish of the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by  [Image: Piscine preservation at the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by

[Image: Piscine preservation at the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Instagram by  [Image: An otherwise unrelated seed x-ray from the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated seed x-ray from the  [Image: “Higashiyama III” (1989) by

[Image: “Higashiyama III” (1989) by

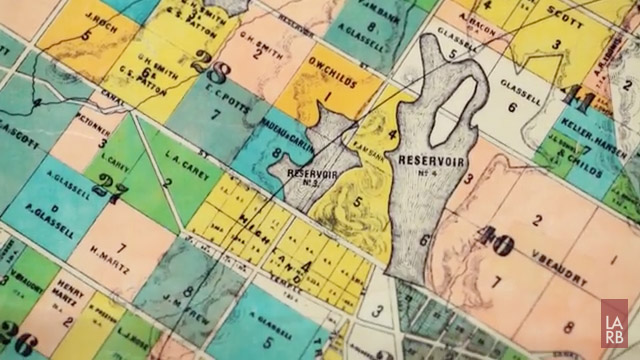

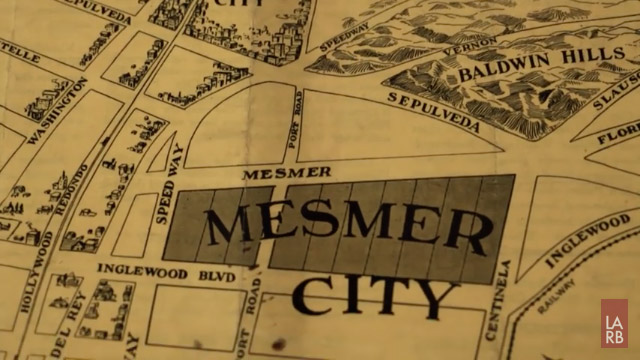

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal

[Image: From an “ongoing speculative proposal  [Image: “Proposal for a

[Image: “Proposal for a  [Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a

[Image: “Speculative proposal showing use of the ‘Popular Pak’, a  [Image: Proposal “

[Image: Proposal “