I was thinking about this whale song bunker idea the other week after reading about the potential for whale song to be used as a form of deep-sea seismic sensing. That original project—with no actual connection to the following news story—proposed using a derelict submarine surveillance station on the coast of Scotland as a site for eavesdropping on the songs of whales.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of whales, courtesy Public Domain Review.]

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image of whales, courtesy Public Domain Review.]

In a paper published in Science last month, researchers found that “fin whale songs can also be used as a seismic source for determining crustal structure. Fin whale vocalizations can be as loud as large ships and occur at frequencies useful for traveling through the ocean floor. These properties allow fin whale songs to be used for mapping out the density of ocean crust, a vital part of exploring the seafloor.”

The team noticed not only that these whale songs could be picked up on deep-sea seismometers, but that “the song recordings also contain signals reflected and refracted from crustal interfaces beneath the stations.” It could be a comic book: marine geologists teaming up with animal familiars to map undiscovered faults through tectonic sound recordings of the sea.

There’s something incredibly beautiful about the prospect of fin whales swimming around together through the darkness of the sea, following geological structures, perhaps clued in to emerging tectonic features—giant, immersive ambient soundscapes—playfully enjoying the distorted reflections of each other’s songs as they echo back off buried mineral forms in the mud below.

I’m reminded of seemingly prescient lyrics from Coil’s song “The Sea Priestess”: “I was woken three times in the night / and asked to watch whales listen for earthquakes in the sea / I had never seen such a strange sight before.”

Someday, perhaps, long after the pandemic has passed, we’ll gather together in derelict bunkers on the ocean shore to tune into the sounds of whales mapping submerged faults, a cross-species geological survey in which songs serve as seismic media.

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the  [Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

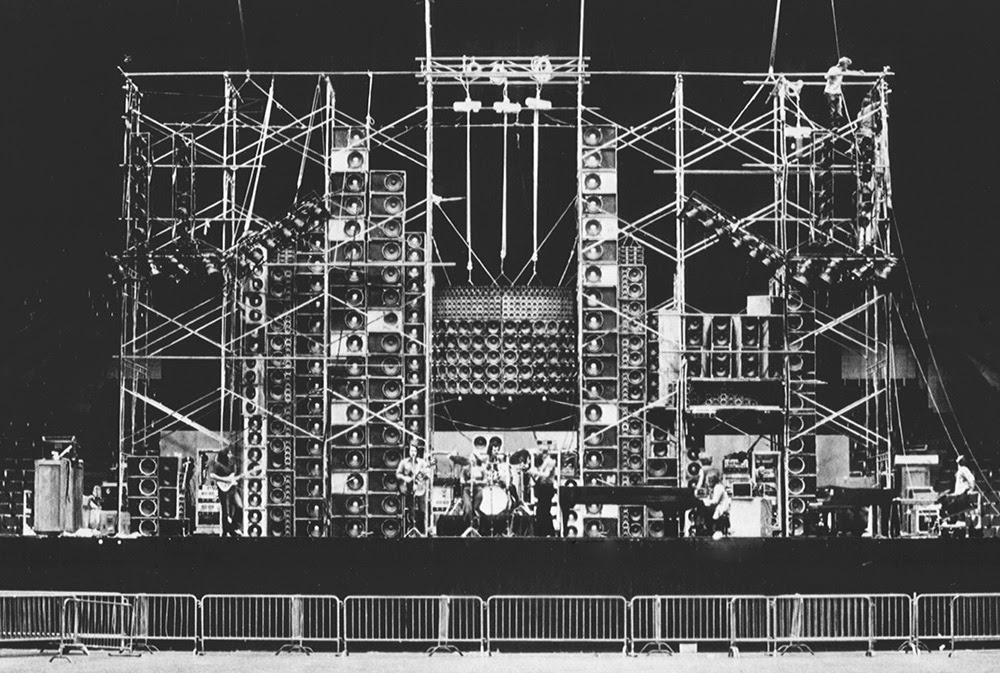

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: A representative

[Image: A representative