[Image: Diagram from The Stones of Venice by John Ruskin.]

[Image: Diagram from The Stones of Venice by John Ruskin.]

There are at least two interesting moments in John Ruskin’s book The Stones of Venice.

One is his description of buttresses.

Buttresses, Ruskin writes, are structures against pressure: a cathedral’s walls want to fall outward, for example, pushed aside by the relentless weight of the roof. But this gravitational pressure can be stabilized by an exoskeleton: a sequence of buttresses that will prevent those walls from collapsing outward.

However, Ruskin points out, there is a similar kind of pressure from the waves of the sea. Think of the curved hull of a ship, he writes, which is internally buttressed against the “crushing force” of the ocean around it. It is a kind of inside-out cathedral.

Consider other high-pressure environments where architecture can thrive—resting in the benthic abyss or twirling through the vacuum of outer space, where offworld stations rotate and spin through exotic gravitational scenarios—and you’ve perhaps envisioned what John Ruskin would be writing about today. Ship-buildings, buttressed against the void.

In any case, for Ruskin, buttresses perform a kind of gravitational judo: he describes “buttresses of peculiar forms, cunning buttresses, which do not attempt to sustain the weight, but parry it, and throw it off in directions clear of the wall.” They shed the load, so to speak, flipping it elsewhere, as if taking advantage of an opponent’s slow and graceless momentum.

…as science advances, the weight to be borne is designedly and decisively thrown upon certain points; the direction and degree of the forces which are then received are exactly calculated, and met by conducting buttresses of the smallest possible dimensions; themselves, in their turn, supported by vertical buttresses acting by weight, and these perhaps, in their turn, by another set of conducting buttresses: so that, in the best examples of such arrangements, the weight to be borne may be considered as the shock of an electric fluid, which, by a hundred different rods and channels, is divided and carried away into the ground.

It’s buttresses buttressing buttresses—or buttresses all the way down.

Ruskin reminds his readers, however, that a buttress’s function can even be seen outdoors, where he specifically cites Swiss landscape defenses. There, Ruskin writes, horizontal buttresses like defensive walls “are often built round churches, heading up hill, to divide and throw off the avalanches.” Again, it’s a question of parrying an oppositional force, deflecting it elsewhere.

[Image: “Profile of a buttress with vertical internal line, when the line of thrust coincides with the axis of the buttress,” taken from a paper called “Milankovitch’s Theorie der Druckkurven: Good mechanics for masonry architecture” by Federico Foce, in Nexus Network Journal.]

[Image: “Profile of a buttress with vertical internal line, when the line of thrust coincides with the axis of the buttress,” taken from a paper called “Milankovitch’s Theorie der Druckkurven: Good mechanics for masonry architecture” by Federico Foce, in Nexus Network Journal.]

From an architectural point of view, you might say that a landscape is stationary until it buckles, shudders, or moves, becoming oceanic, heaving like the sea.

Or, to be pretentious and quote myself from an op-ed in the New York Times, “the ground itself is a kind of ocean in waiting. We might say that [the Earth] is a marine landscape, not a terrestrial one, a slow ocean buffeted by underground waves occasionally strong enough to flatten whole cities. We do not, in fact, live on solid ground: We are mariners, rolling on the peaks and troughs of a planet we’re still learning to navigate. This is both deeply vertiginous and oddly invigorating.”

For Ruskin, the buttress is an architectural technology—a spatial tool—that can be built to anticipate this act of marine transformation, a device that can prepare our buildings and cities to resist violent events in the landscape they are built upon.

With this in mind, it’s worth recalling a recent experiment that showed buildings can be partially shielded from the effects of earthquakes. An “invisibility cloak,” as researchers somewhat hyperbolically described it back in 2013, would use a “regular grid of cylindrical and empty boreholes” drilled into the earth to absorb and deflect seismic waves and thus protect certain structures from damage.

They would “parry it,” as Ruskin once wrote, “and throw it off in directions clear” of the city. In Ruskin’s terms, in other words, they would be buttresses: empty void-silos in the earth that nevertheless function like the exoskeletal cage of a cathedral or the internal ribs of a ship at sea.

[Image: Glacial logics diagrammed in The Stones of Venice by John Ruskin.]

[Image: Glacial logics diagrammed in The Stones of Venice by John Ruskin.]

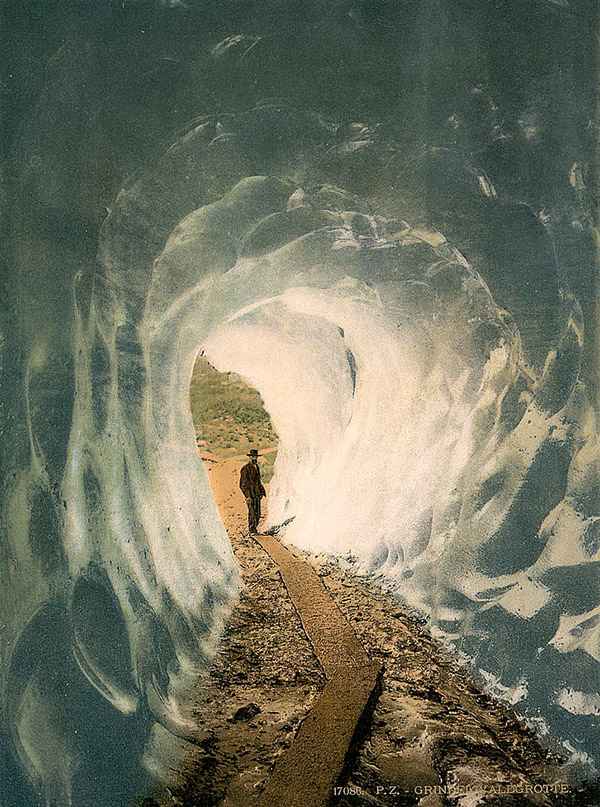

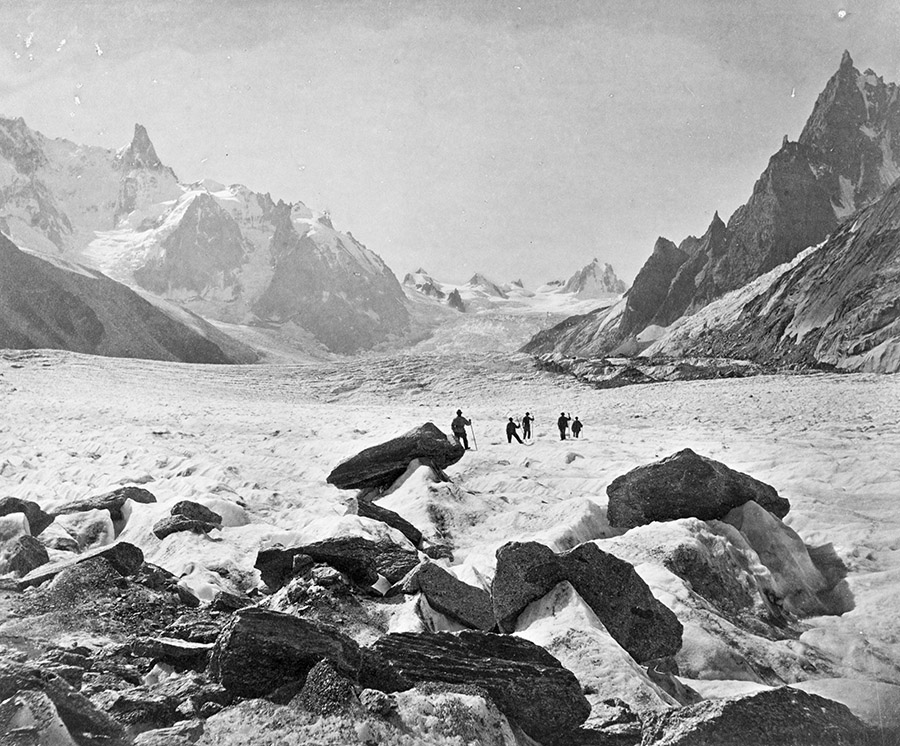

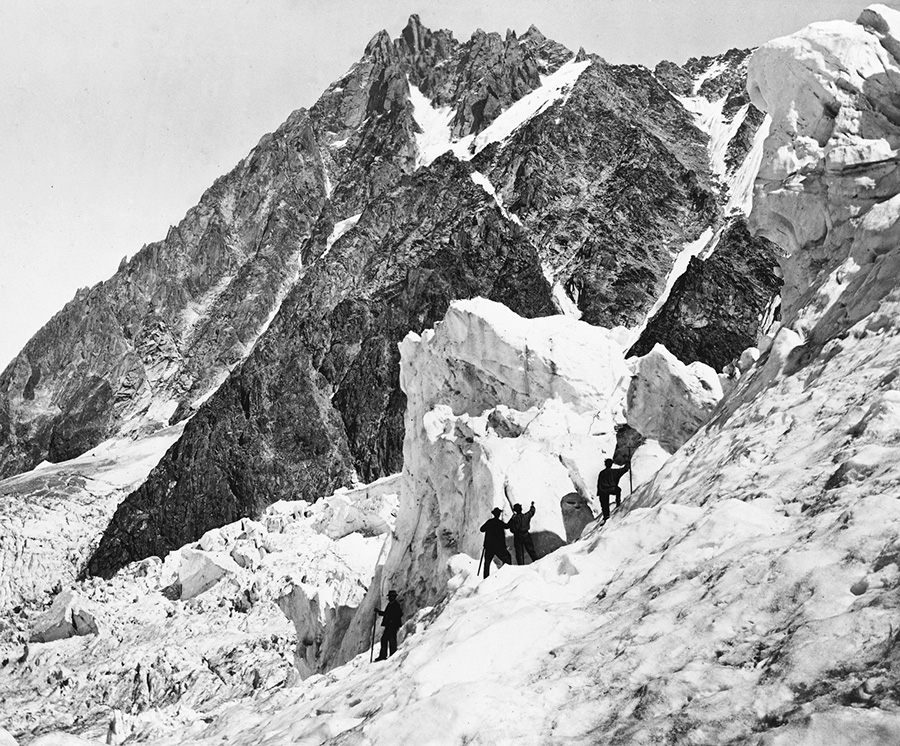

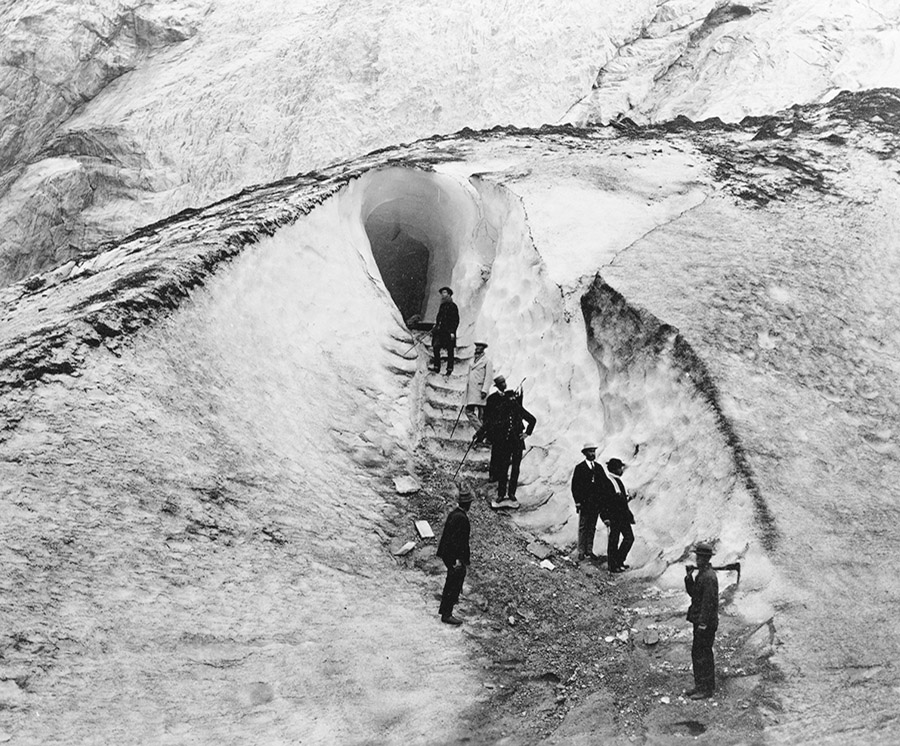

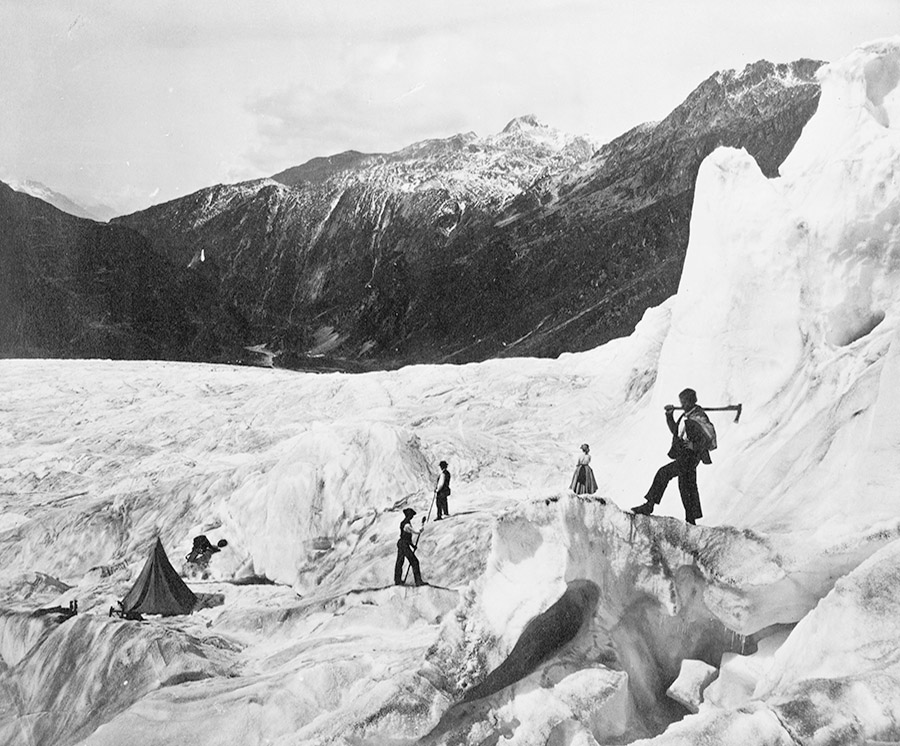

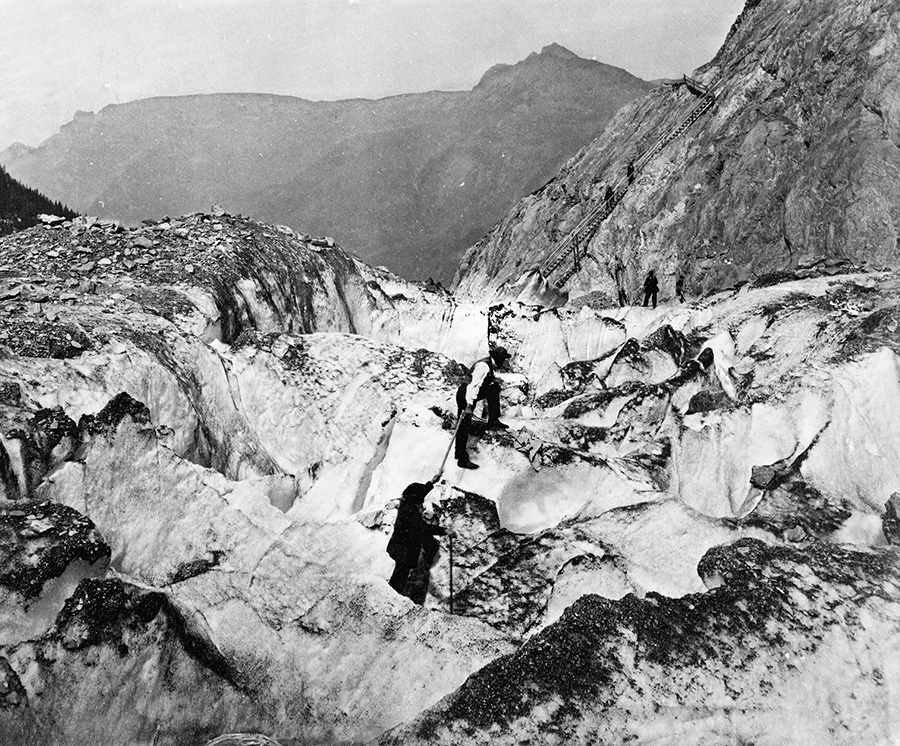

The second interesting thing from The Stones of Venice—among many others, to be sure, but I will only focus on two here—is that, amazingly, for a book published back in 1853, Ruskin scales his analysis up to the point of suggesting that glaciers should be considered as complex architectural objects.

Ruskin describes “a curve about three quarters of a mile long,” for example, “formed by the surface of a small glacier of the second order.” This curve, he writes, is “the most beautiful simple curve I have ever seen in my life.” So, he wonders, how could it be applied to architecture? How could we learn from glaciers?

At this point, Ruskin draws a diagram—the one I’ve scanned, above—to highlight a variety of nested curves that he believes are hiding inside a particular glacier. These are organizational systems that extend for many miles at a time through the ice and that allegedly entail geometric lessons for architects.

The idea here—that Ruskin was trying to extract architectural lessons from glaciers nearly two centuries ago—is incredible to me.

After all, if the Gothic is an architectural language that, as writers such as Lars Spuybroek have compellingly shown, draws from the natural vocabulary of leaves, plants, tree roots, and so on, then this means that Ruskin is suggesting—in 1853!—a kind of Glacial Gothic, an architectural lesson drawn from continent-spanning masses of ice.

[Image: “A Crack in an Antarctic Ice Shelf Is 8 Miles From Creating an Iceberg the Size of Delaware”; image via Ohio State University.]

[Image: “A Crack in an Antarctic Ice Shelf Is 8 Miles From Creating an Iceberg the Size of Delaware”; image via Ohio State University.]

I’m reminded of an old t-shirt produced by the band Godflesh that described their music as an “Avalanche On Pause.”

This is a very Ruskinian description, we might say in the present context.

An avalanche on pause brings together Ruskin’s interests in landscape-scale structural events—such as glaciers and landslides—with his attention to the mechanics of cathedrals built to resist such imposing pressures. To freeze them in place. To press pause.

(Thanks to Marc Weidenbaum for reminding me of that Godflesh shirt many years ago.)

[Images: Muons beneath the Alps;

[Images: Muons beneath the Alps;  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy

[Images: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: From India’s

[Image: From India’s  [Image: Pluto, via

[Image: Pluto, via

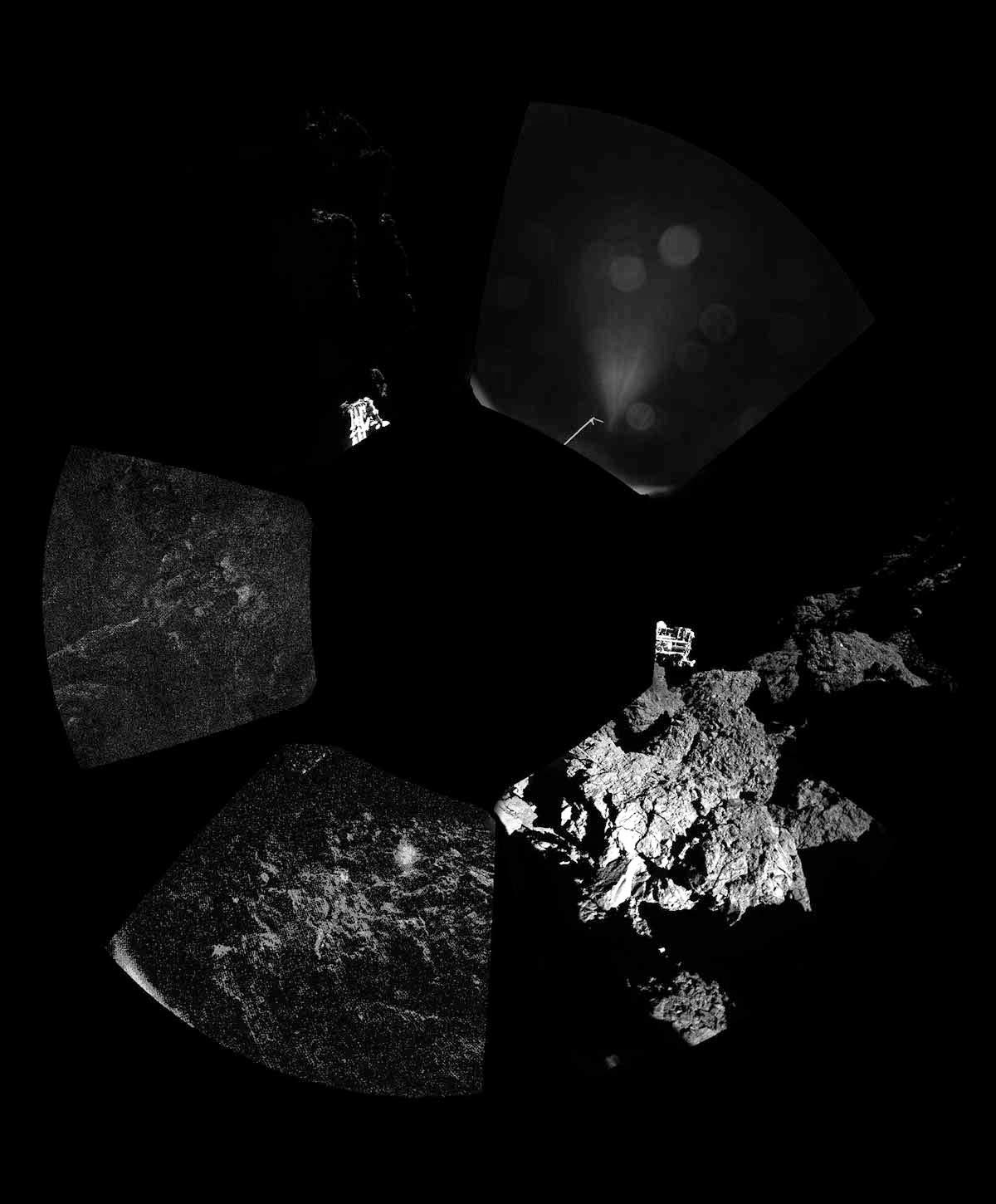

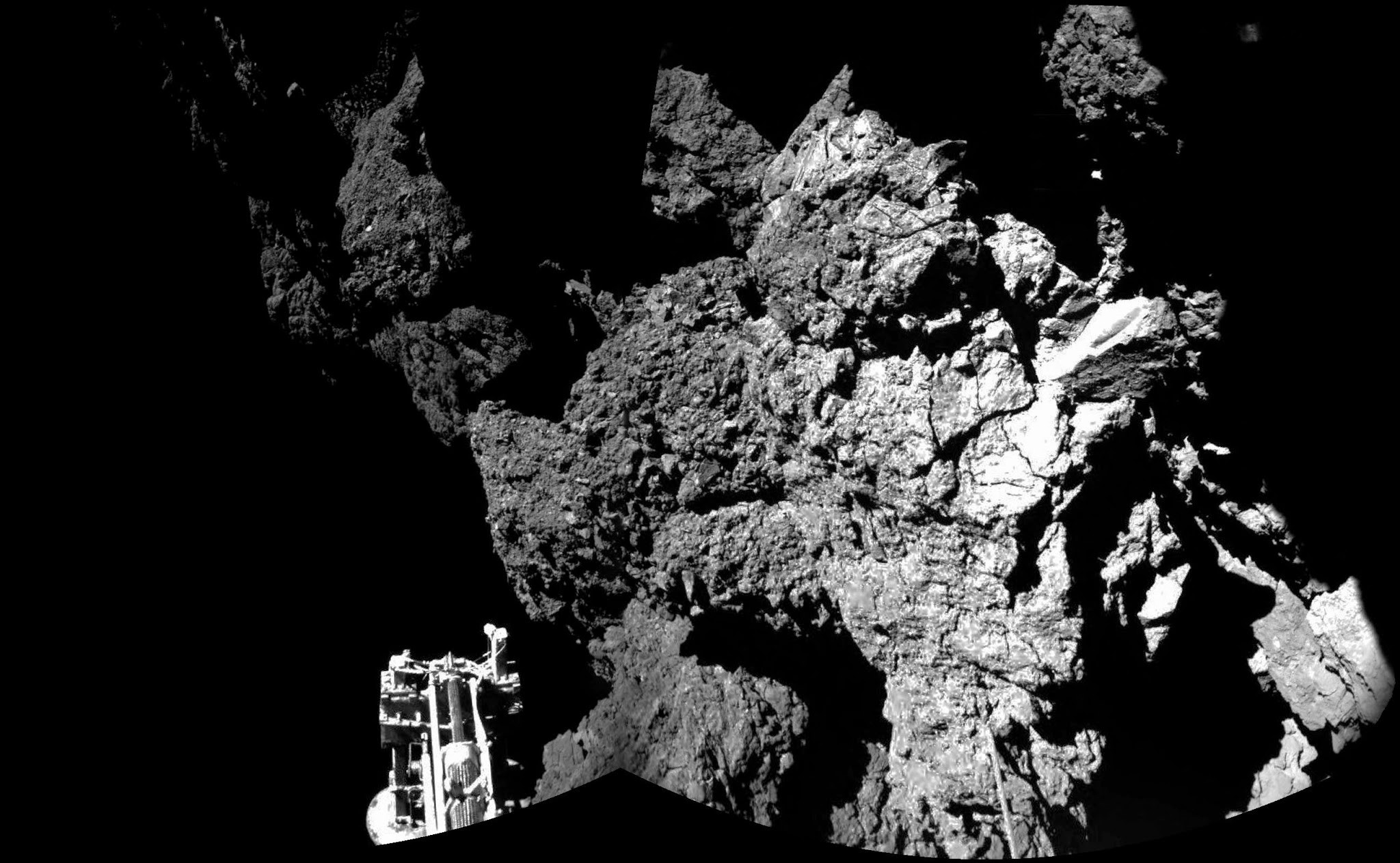

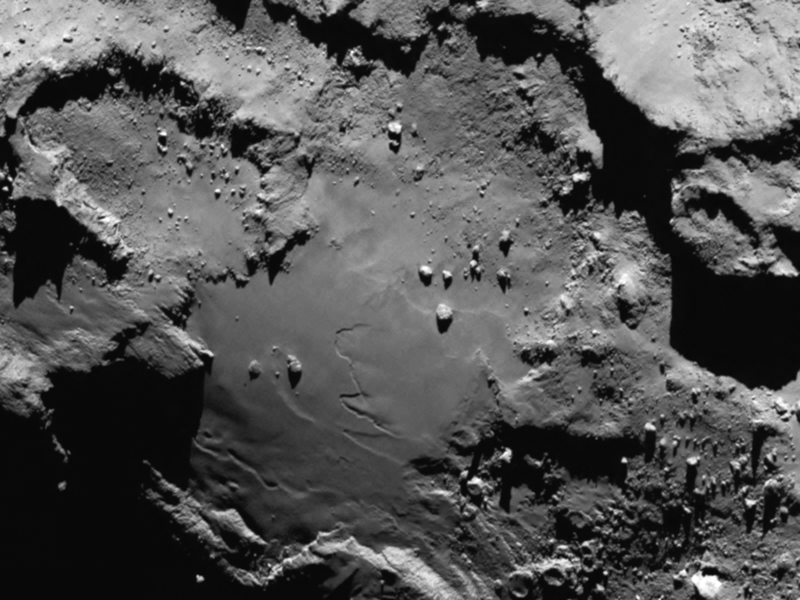

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

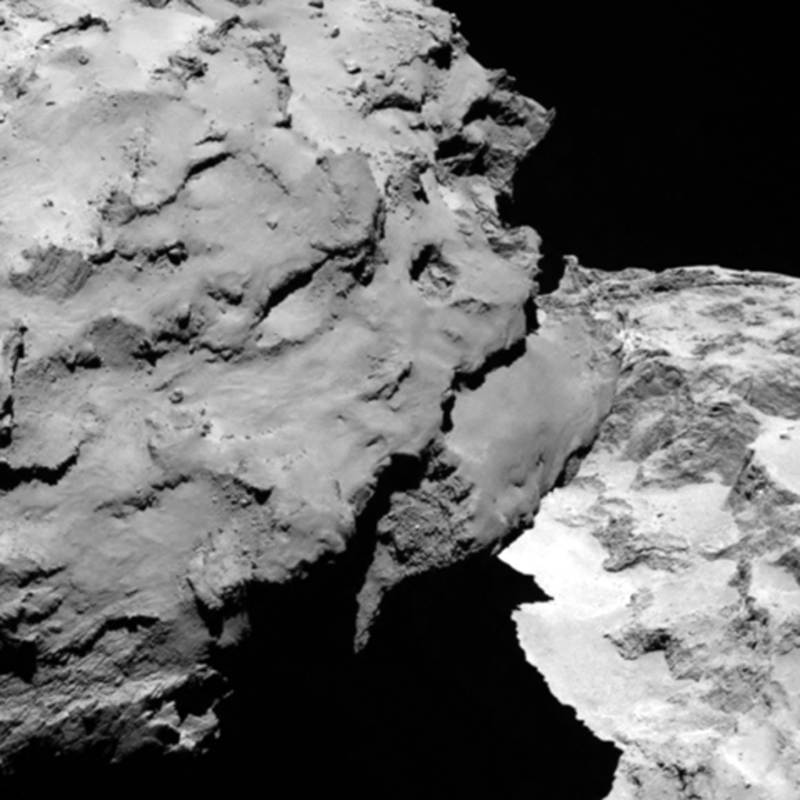

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via

[Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

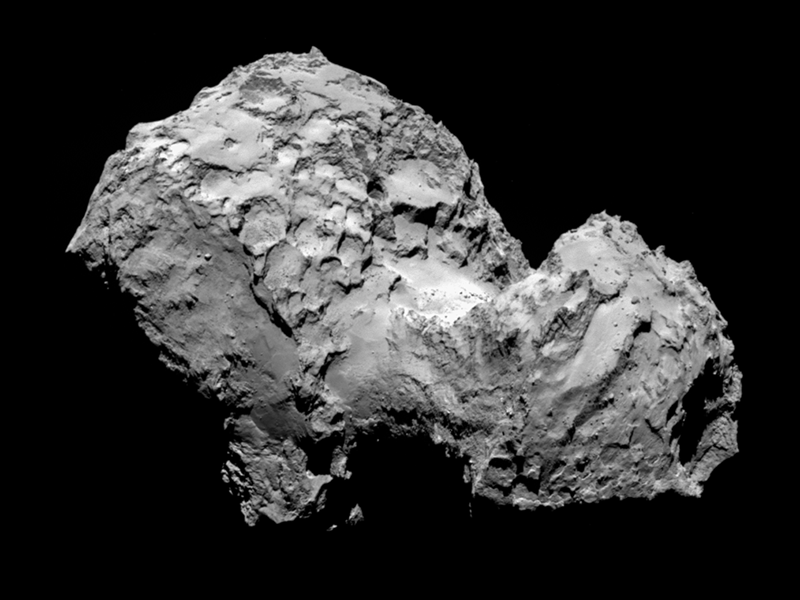

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: From

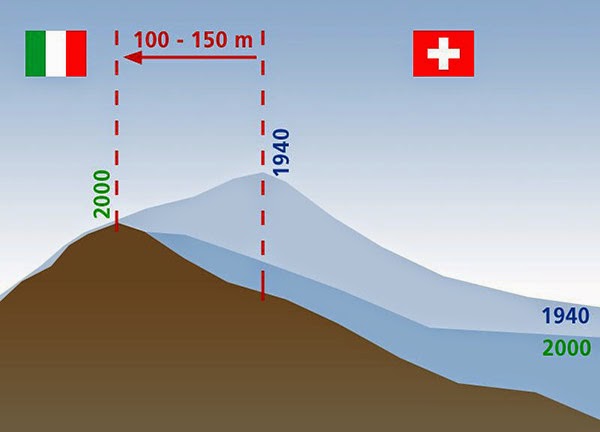

[Image: From  [Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

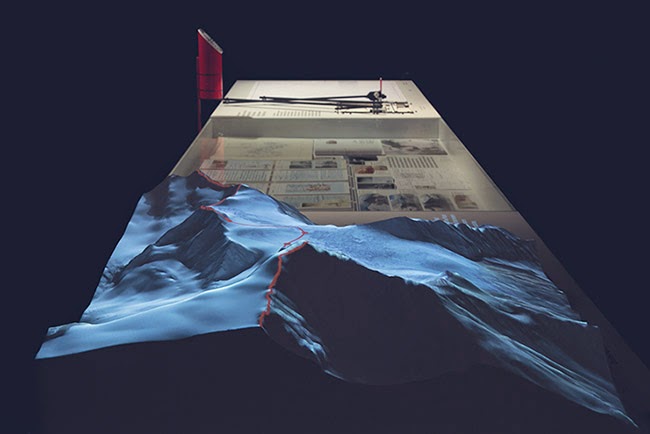

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Walking into a glacier: “

[Image: Walking into a glacier: “

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

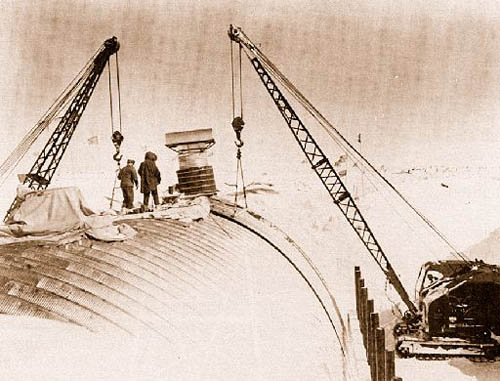

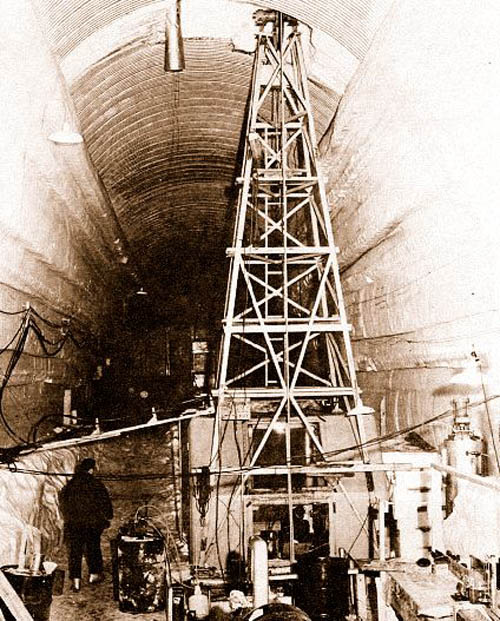

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

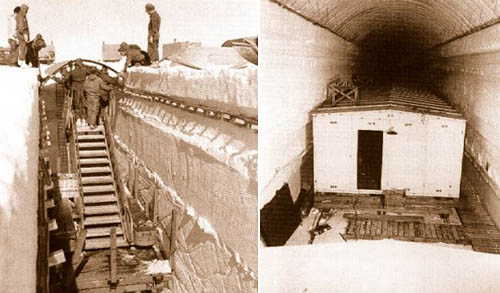

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

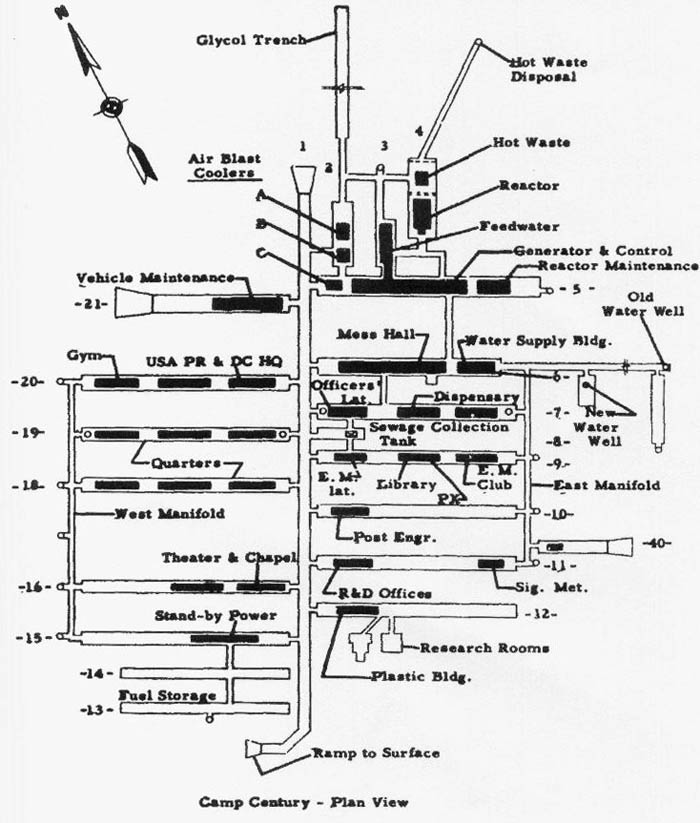

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via  [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

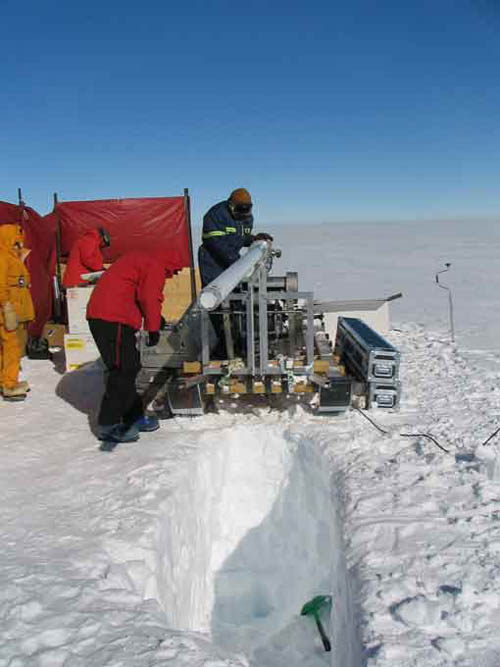

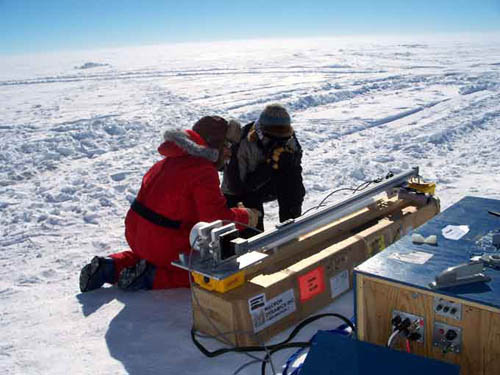

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From