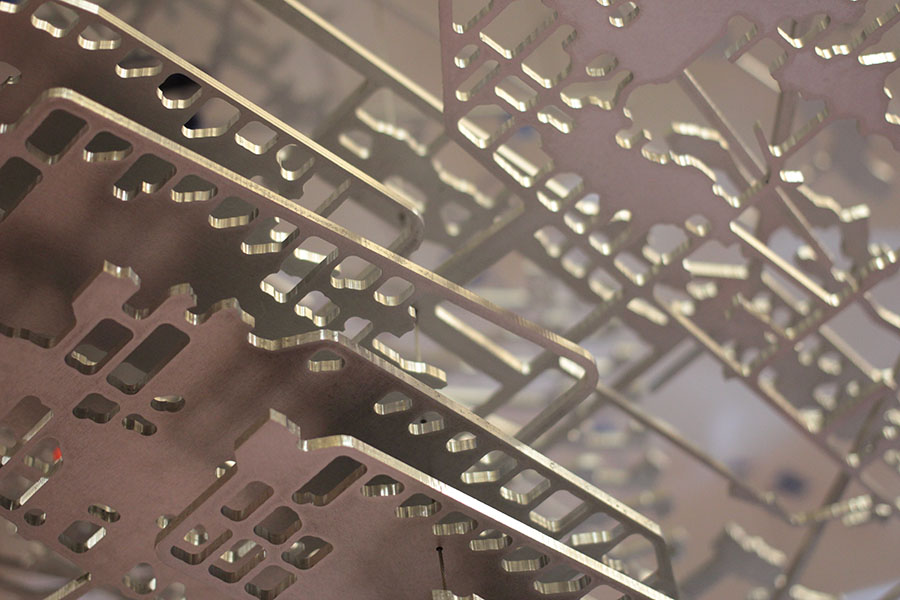

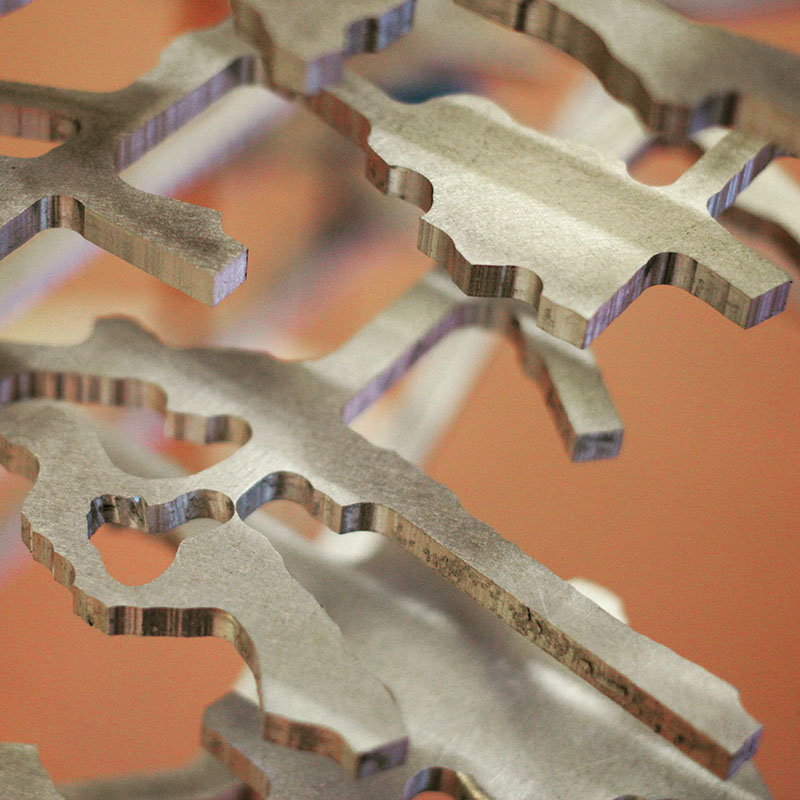

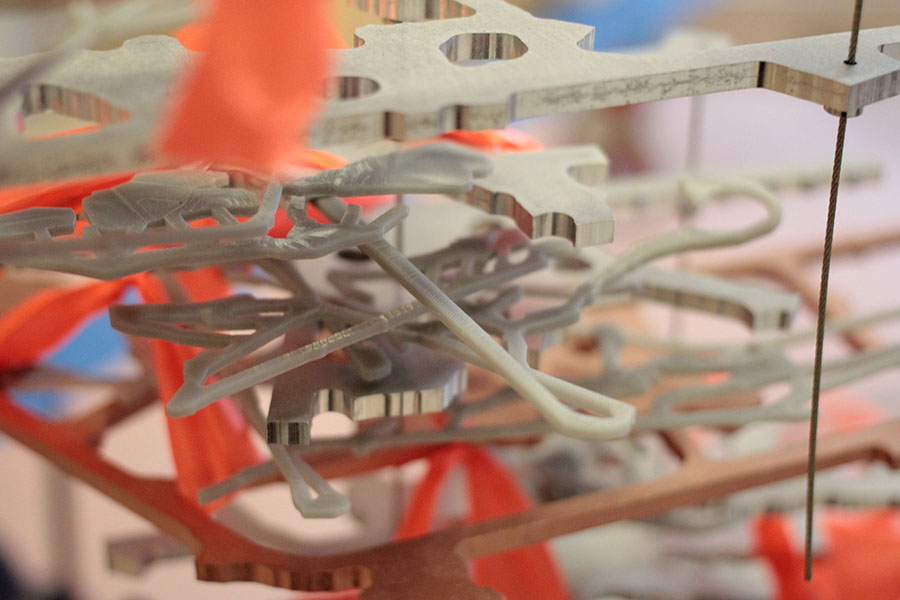

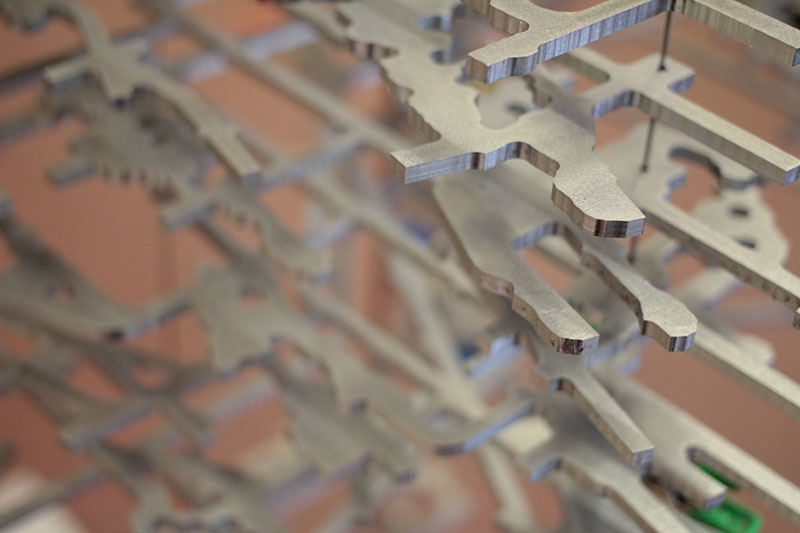

[Image: Close-up of the 2010 State Geologic Map of California].

[Image: Close-up of the 2010 State Geologic Map of California].

An interesting story published last month in the L.A. Times explored the so-called “sweet spot” for digging tunnels along the California/Mexico border.

“Go too far west,” reporter Jason Song explained, “and the ground will be sandy and potentially soggy from the water of the Pacific Ocean. That could lead to flooding, which wouldn’t be good for the drug business. Too far east and you’ll hit a dead end of hard mountain rock.”

However, Song continues, “in a strip of land that runs between roughly the Tijuana airport and the Otay Mesa neighborhood in San Diego, there’s a sweet spot of sandstone and volcanic ash that isn’t as damp as the oceanic earth and not as unyielding as stone.”

More accurately speaking, then, it is less a sweet spot than it is a soft one, a location of potential porosity where two nations await subterranean connection. It is all a question of geology, in other words—or the drug tunnel as landscape design operation.

[Image: Nogales/Nogales, via Google Maps].

[Image: Nogales/Nogales, via Google Maps].

With the very obvious caveat that this next article is set along the Arizona/Mexico border, and not in the San Diego neighborhood of Otay Mesa, it is nonetheless worth drawing attention back to an interesting article by Adam Higginbotham, written in 2012 for Bloomberg, called “The Narco Tunnels of Nogales.”

There, Higginbotham describes a world of abandoned hotel rooms in Mexico linked, by tunnel, to parking spots in the United States; of streets subsiding into otherwise unknown narco-excavations running beneath; and of an entire apartment building on the U.S. side of the border whose strategic value is only revealed later once drug tunnels begin to converge in the ground beneath it.

Here, too, though, Higginbotham also refers to “a peculiar alignment of geography and geology,” noting that the ground conditions themselves are particularly amenable to the production of cross-border subterranea.

However, the article also suggests that “the shared infrastructure of a city”—that is, Nogales, Arizona, and its international counterpart, Nogales, Mexico—already, in a sense, implies this sort of otherwise illicit connectivity. It is literally built into the fabric of each metropolis:

When the monsoons begin each summer, the rain that falls on Mexico is funneled downhill, gathering speed and force as it reaches the U.S. In the 1930s, in an attempt to control the torrent of water, U.S. engineers converted the natural arroyos in Nogales into a pair of culverts that now lie beneath two of the city’s main downtown streets, Morley Avenue and Grand Avenue. Beginning in Mexico, and running beneath the border before emerging a mile into the U.S., the huge tunnels—large enough to drive a car through—created an underground link between the two cities, and access to a network of subterranean passages beneath both that has never been fully mapped.

This rhizomatic tangle of pipes, tubes, and tunnels—only some of which are official parts of the region’s hydrological infrastructure—results in surreal events of opportunistic spelunking whereby “kids would materialize suddenly from the drainage grates,” or “you would see a sewer plate come up in the middle of the street, and five people would come up and run.”

Briefly, I’m reminded of a great anecdote from Jon Calame’s and Esther Charlesworth’s book Divided Cities, where the split metropolis of Nicosia, Cyprus, is revealed to be connected from below, served by a shared sewage plant “where all the sewage from both sides of the city is treated.” The authors interview the a local waste manager, who jokes that “the city is divided above ground but unified below.”

In any case, the full article is worth a read, but a tactical geological map revealing sites of likely future tunneling would be a genuinely fascinating artifact to see. I have to assume that ICE or Homeland Security—let alone the cartels—already have such a thing.

(L.A. Times article originally spotted via Nate Berg).

[Image: Drone footage of a Cornwall garden sinkhole, via the

[Image: Drone footage of a Cornwall garden sinkhole, via the  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy

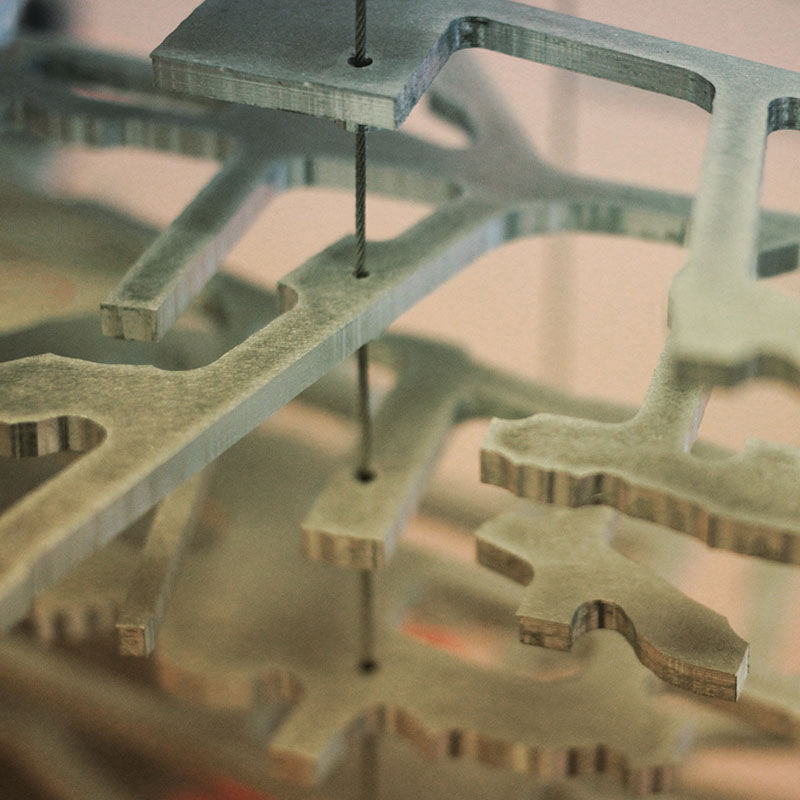

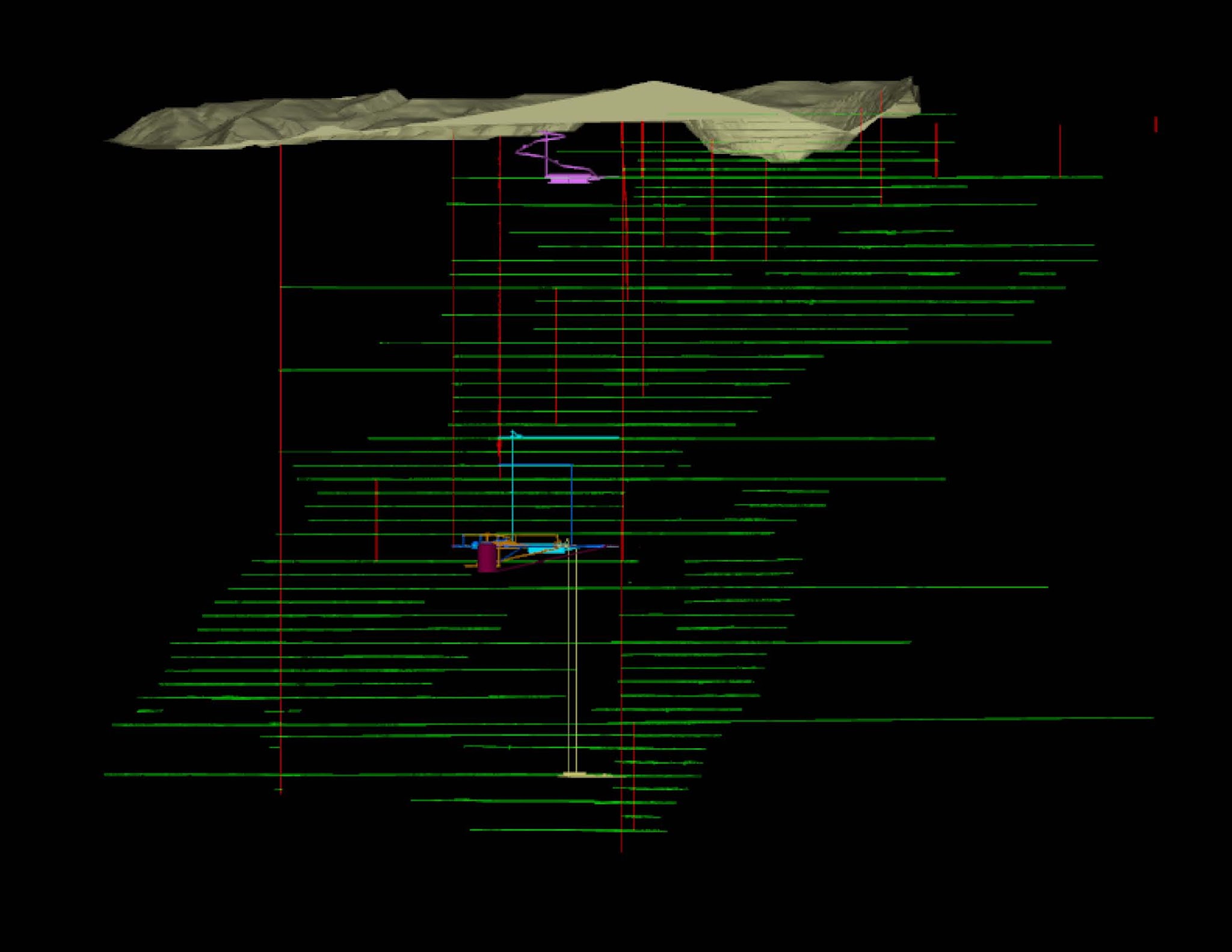

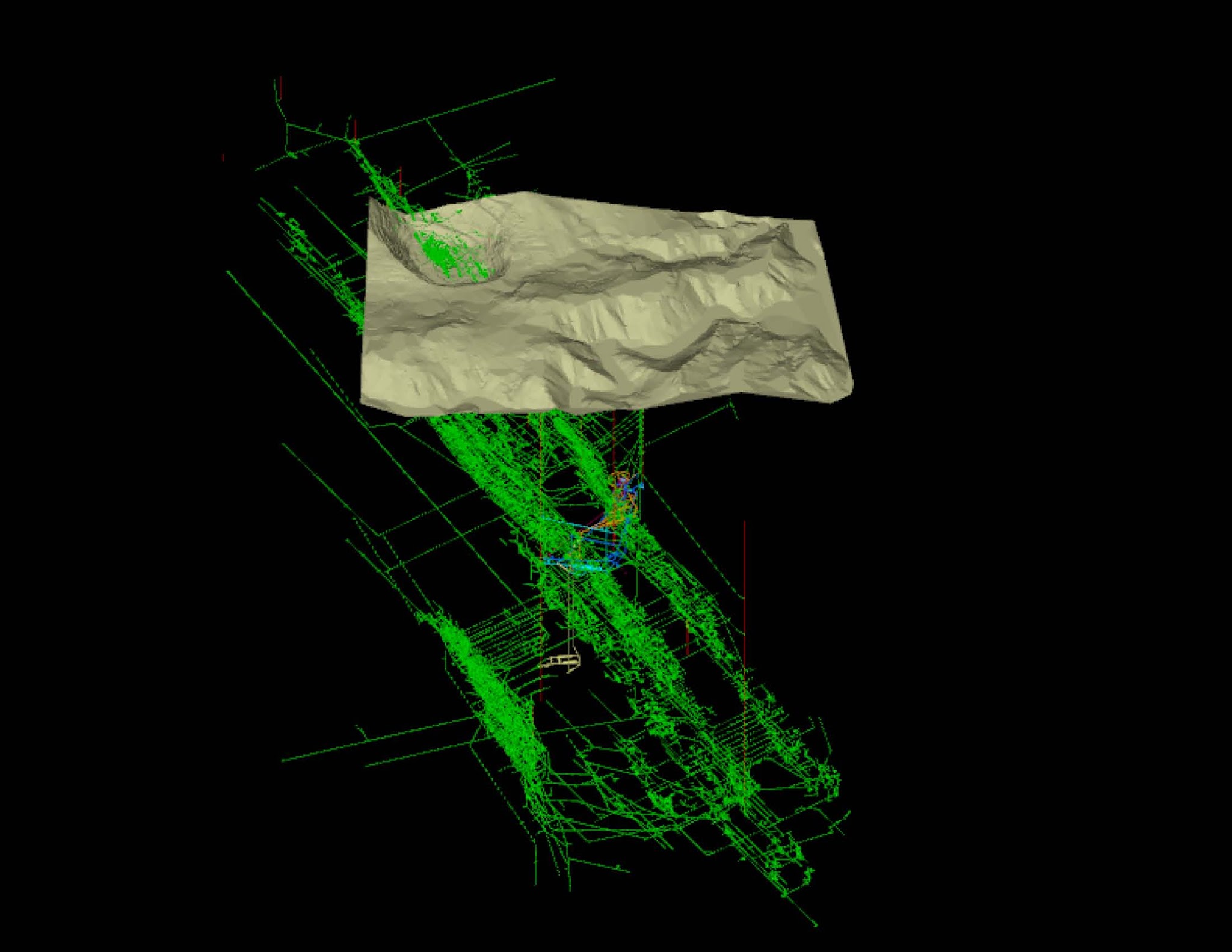

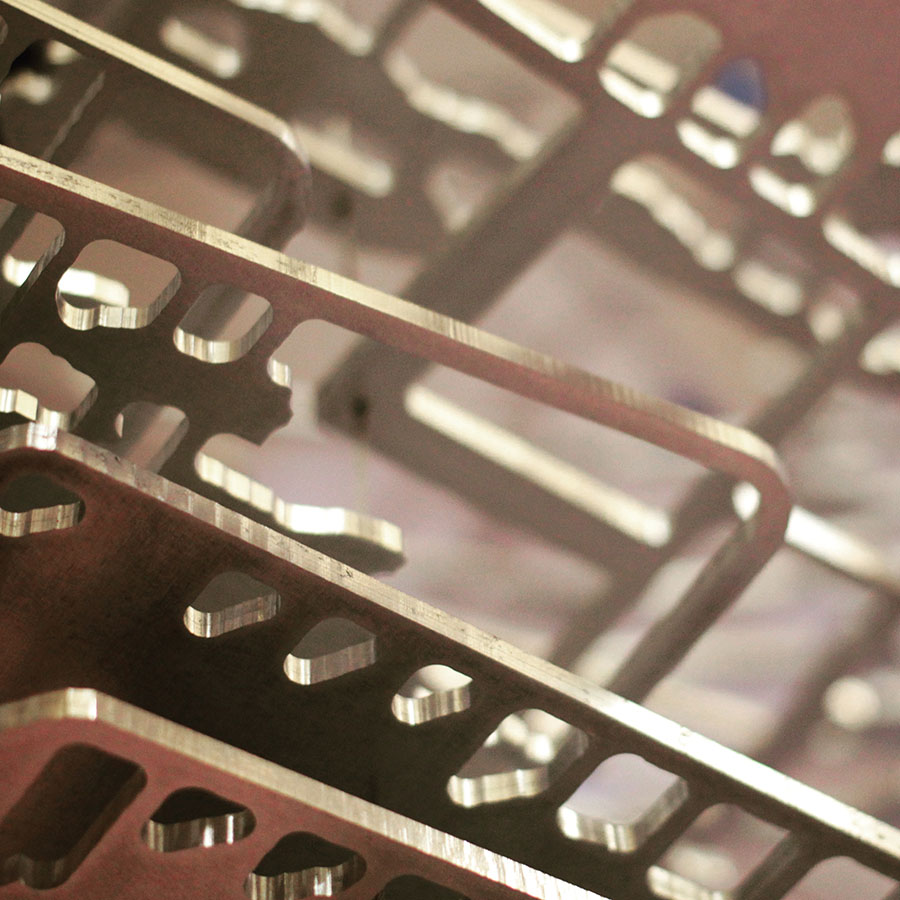

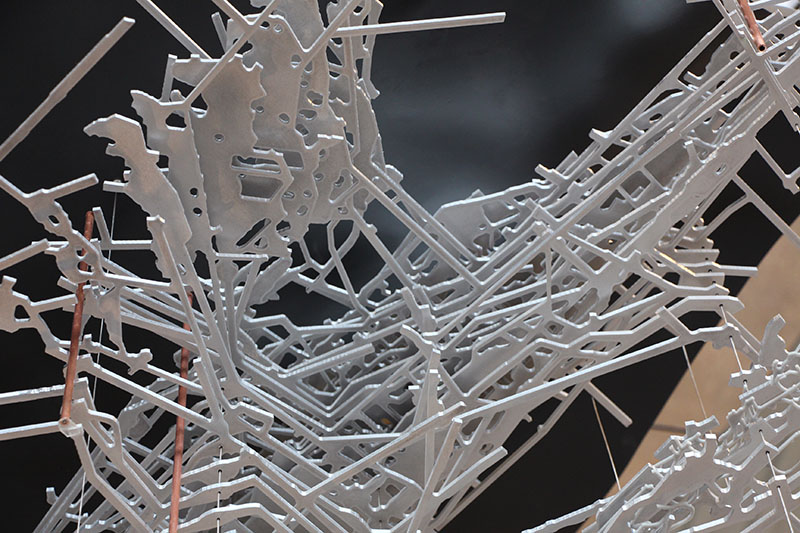

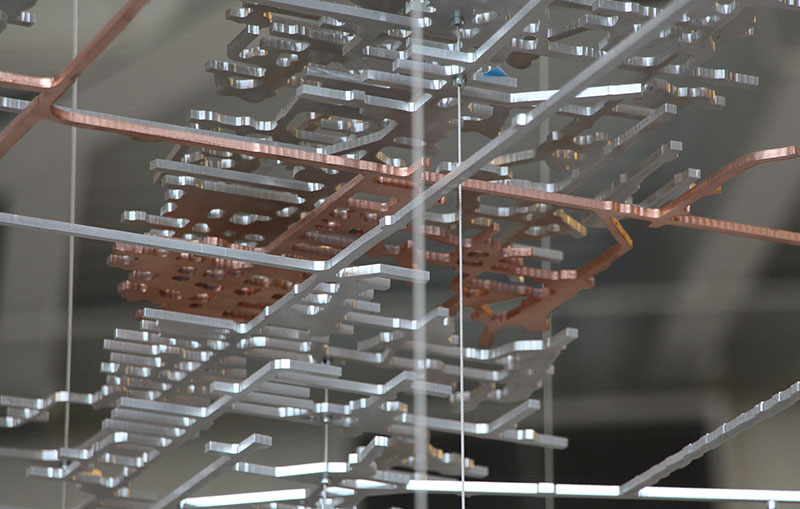

[Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via  [Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Assembly of the model by

[Image: Assembly of the model by

[Images: Model by

[Images: Model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by  [Image: Assembly of the model by

[Image: Assembly of the model by  [Image: Assembling the model by

[Image: Assembling the model by  [Image: Model by

[Image: Model by

[Images: The model seen in situ, by

[Images: The model seen in situ, by  [Image: The model by

[Image: The model by

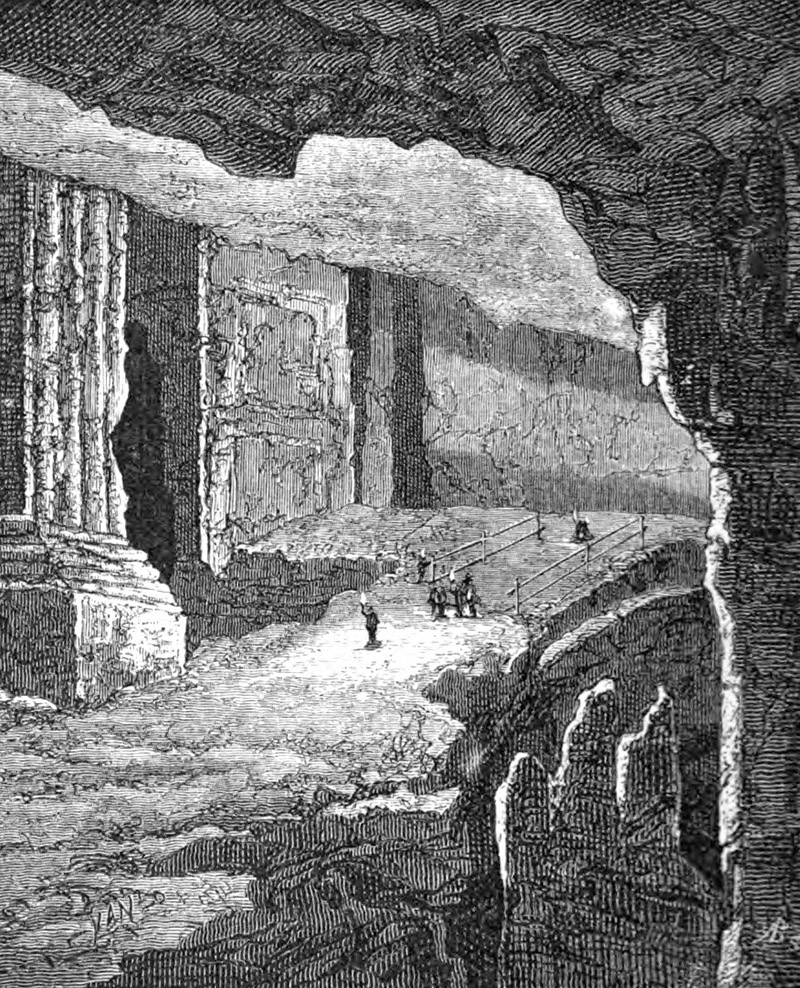

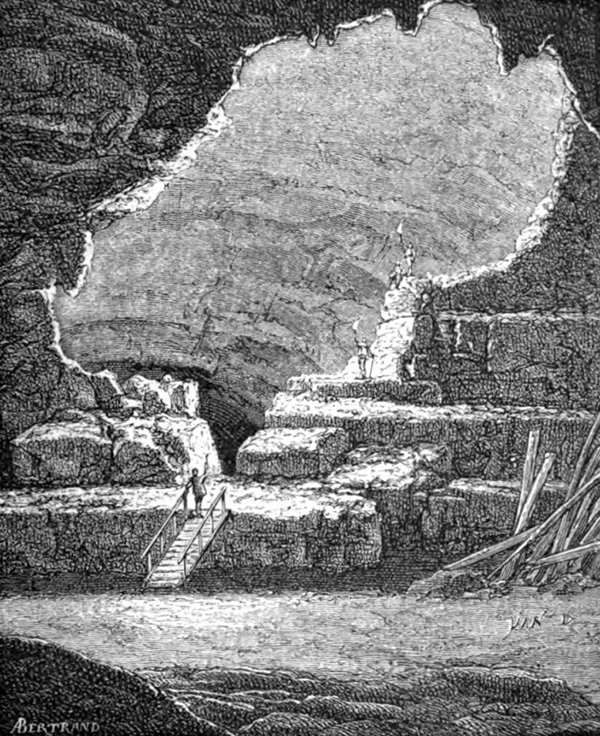

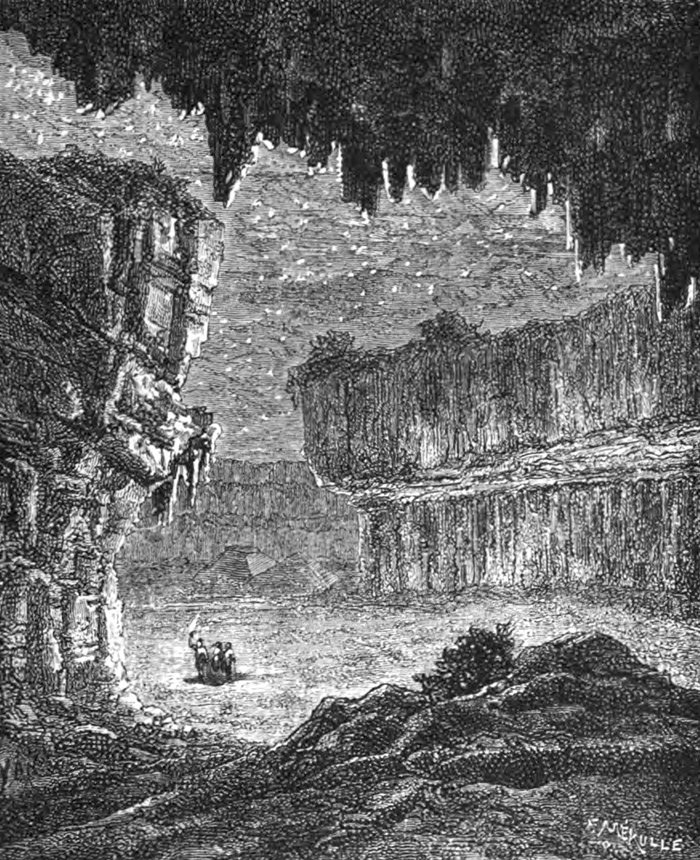

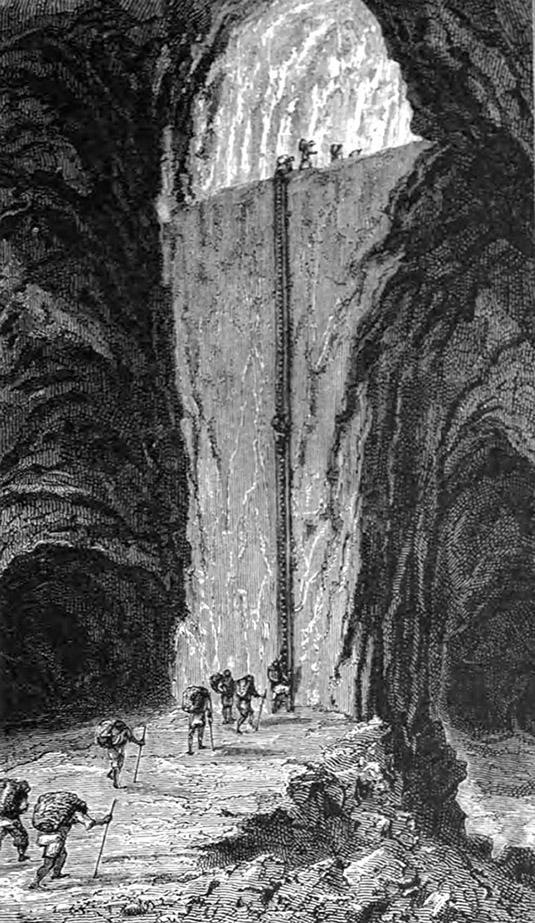

[Image: Descending into Mammoth Cave, from

[Image: Descending into Mammoth Cave, from  [Image: A room in Mammoth Cave known as “The Maelstrom,” from

[Image: A room in Mammoth Cave known as “The Maelstrom,” from  [Image: A vast underground room filled with “a silent, terrible solitude,” from

[Image: A vast underground room filled with “a silent, terrible solitude,” from  [Image: An unfortunately rather low-res image from

[Image: An unfortunately rather low-res image from

[Image: An only conceptually related photo

[Image: An only conceptually related photo

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

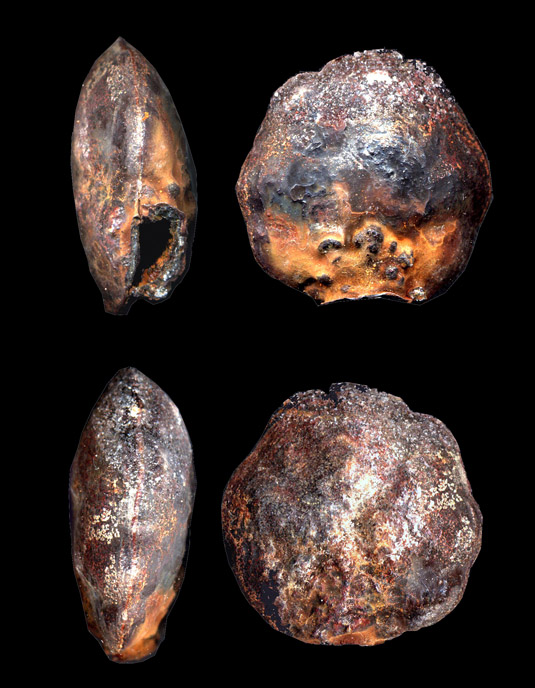

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by  [Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by

[Image: Metal shells growing in the darkness of abandoned mines; photo by  [Image: An “

[Image: An “

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

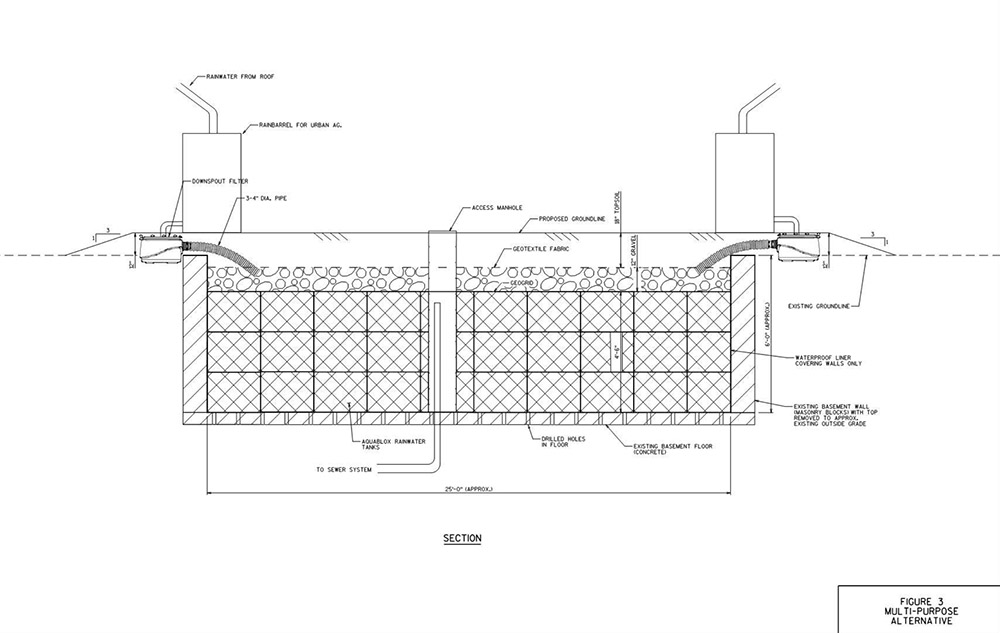

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the

[Image: “Riggers install a lightning rod” atop the Empire State Building “in preparation for an investigation into lightning by scientists of the General Electric Company” (1947), via the  [Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via

[Image: Lightning storm over Boston; via  [Image: Lightning via

[Image: Lightning via