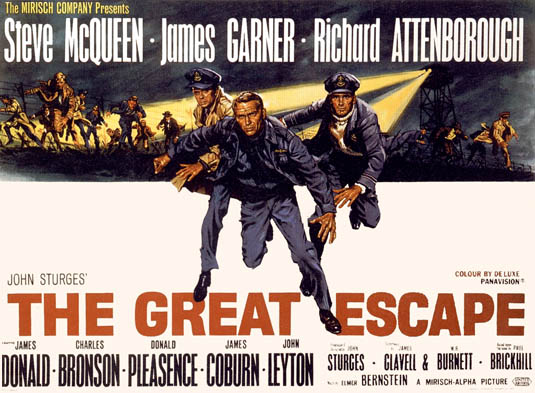

[Image: The Great Escape from MGM].

[Image: The Great Escape from MGM].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley, written as part of Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists.

Alongside The Dam Busters and The Wooden Horse, The Great Escape was shown on British TV at least once a month when I was growing up. It is such familiar, comforting fare that, in a 2006 poll, Britons voted The Great Escape their third choice for a film worth watching on Christmas Day (It’s A Wonderful Life and The Wizard of Oz were first and second choice, respectively).

A large part of its appeal, at least for me, lies in the Boy’s Own adventure-style spirit and Heath Robinson-esque ingenuity of the Allied POWs.

The movie begins with the most experienced and determined Allied escapologists arriving at the newly constructed, supposedly escape-proof Stalag Luft III. Its resistance to casual, opportunistic break outs is demonstrated in the first few minutes, as POWs unsuccessfully attempt to slip out hidden under tree branches, disguised as Russian laborers, and in the blind spots of the guard towers.

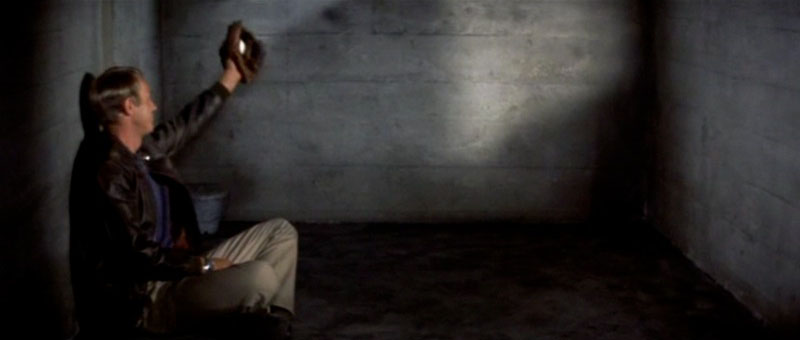

[Image: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Image: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

An altogether more rigorous approach is required, and, under the direction of Richard Attenborough’s Squadron Leader Bartlett, the entire camp is organized into a tunnel-digging machine, with a strict division of labor, assembly-line document- and clothing-production techniques, and a suite of redundant underground infrastructure (tunnels “Tom,” “Dick,” and the ultimately successful “Harry”).

As in A Man Escaped, breaking out requires “the strategic dismantling and reassembly of all designed objects that aren’t architecture”: powdered milk cans, socks, and bunk bed slats are transformed into tunnel ventilation pumps, supports, and trouser-mounted soil disposal devices.

And, as in Grand Illusion, there is a distinct sense that tunneling is a codified sport, bound to be played in prison camps. Certainly, the Allied POWs seem to be motivated as much by a boyish delight in outwitting the Germans through their own ingenuity and teamwork as by a sense of duty or passionate desire to return home. Stalag Luft III, in this view, is something like a game level, challenging seasoned players to apply their existing tunneling techniques in innovative new ways. (Intriguingly, the camp was used as the basis for Dulag IIIA in the first installment of Call of Duty).

If the design of prison camps and the sport of tunneling have co-evolved from World War I’s Grand Illusion to World War II’s Great Escape, then so, too, has the theater of war, from the defined battlefield of the trenches to a total war embedded into and dispersed throughout civilian landscapes.

The second half of The Great Escape, following the trajectories of those who successfully tunneled out of Stalag Luft III, reveals that, in fact, most of the European continent is a prison camp of sorts, booby-trapped with English-speaking Gestapo, and with its safe havens (Switzerland and Spain) ring-fenced with barbed wire and mountain ranges.

[Images: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Images: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

Finally, Steve McQueen, the “Cooler King,” provides future generations of filmmakers with an iconic image of the spatial and temporal experience of solitary confinement: a rubber ball, repetitively bounced off cell walls as if both defining and testing the limits those walls pose to free motion. From The Shining to The Simpsons to Ryan Reynolds in Safe House, the endlessly bouncing ball has since become visual shorthand, indicating that a character is trapped, whether their prison is mental, physical, or both.

(Nicola Twilley is the author of Edible Geography).

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

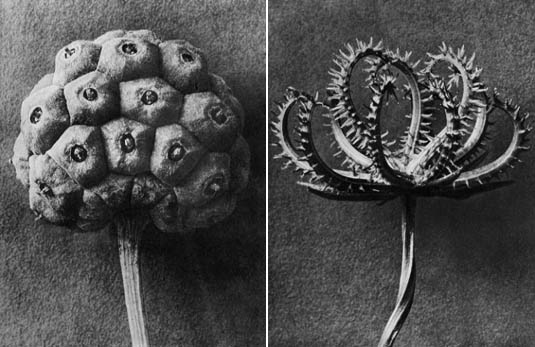

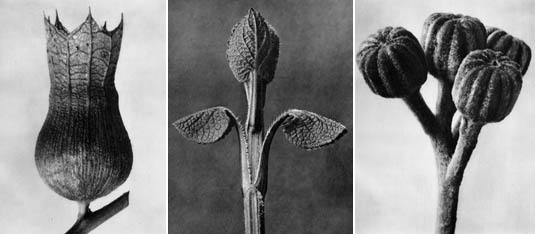

[Images: Botanical photogravures by

[Images: Botanical photogravures by  [Images: More extraordinary photogravures by

[Images: More extraordinary photogravures by  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: Dye-tracing cave systems; note that the chemical used is supposedly non-toxic].

[Images: Dye-tracing cave systems; note that the chemical used is supposedly non-toxic]. [Images: Dye-tracing caves].

[Images: Dye-tracing caves].

[Image: An unrelated photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: An unrelated photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

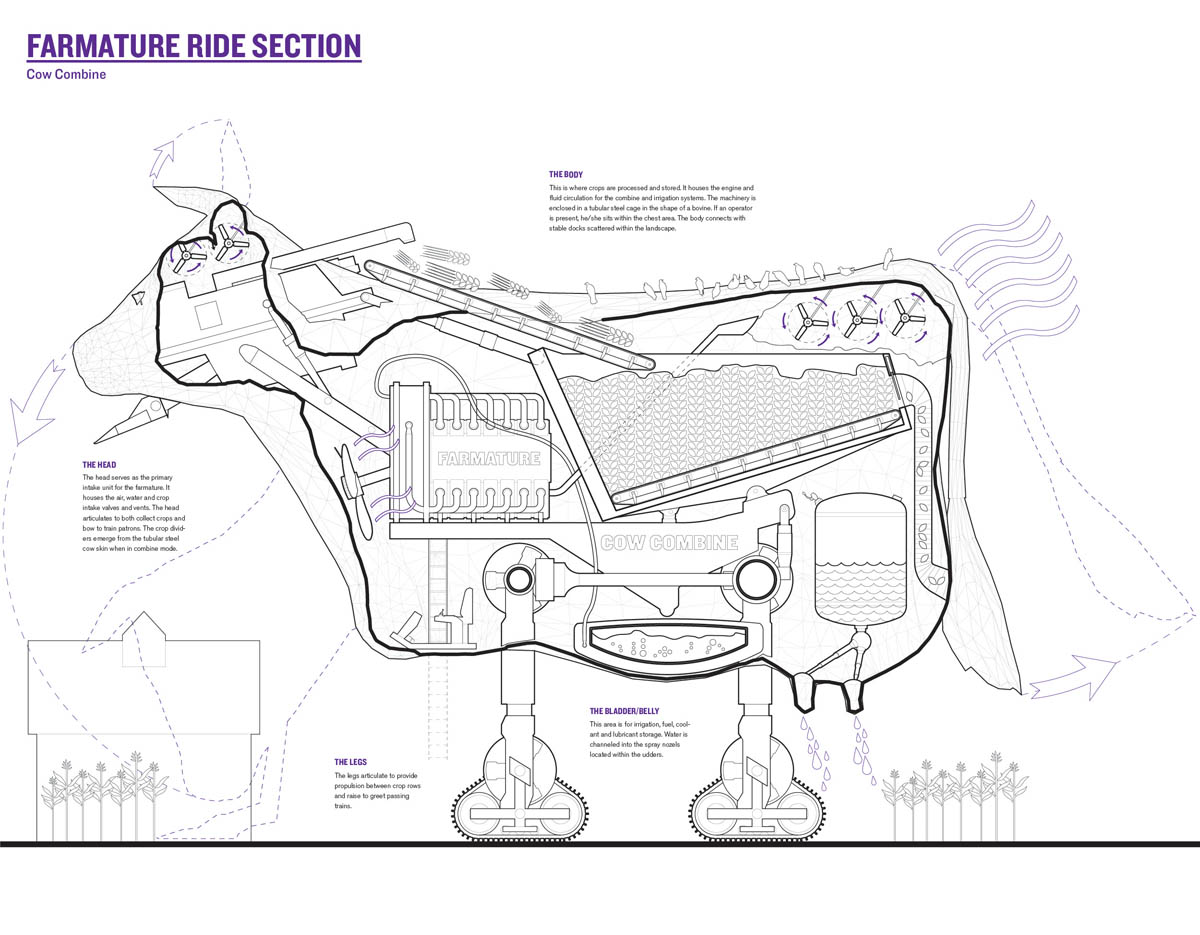

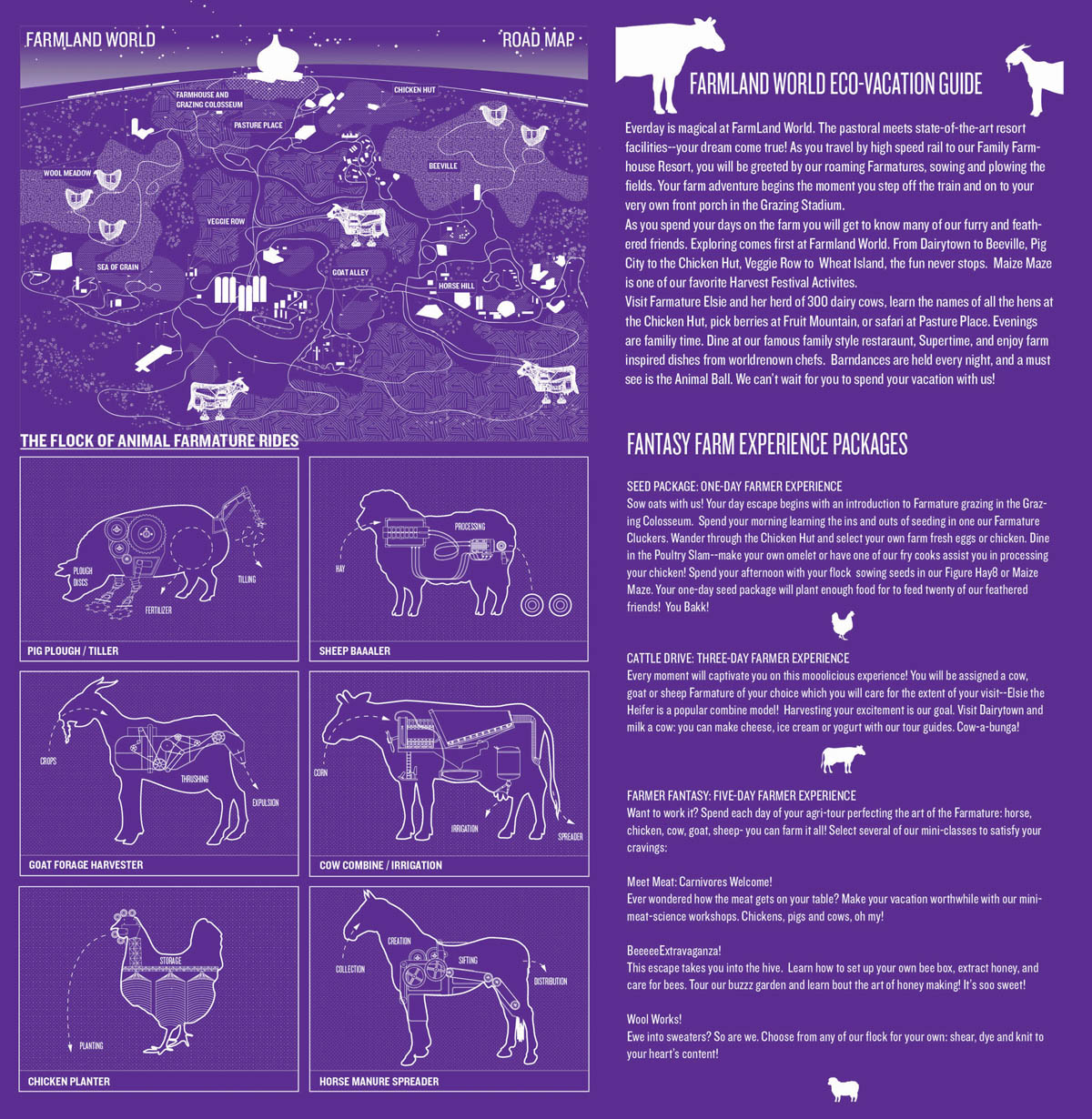

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “

[Images: The robotic super-cows of “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

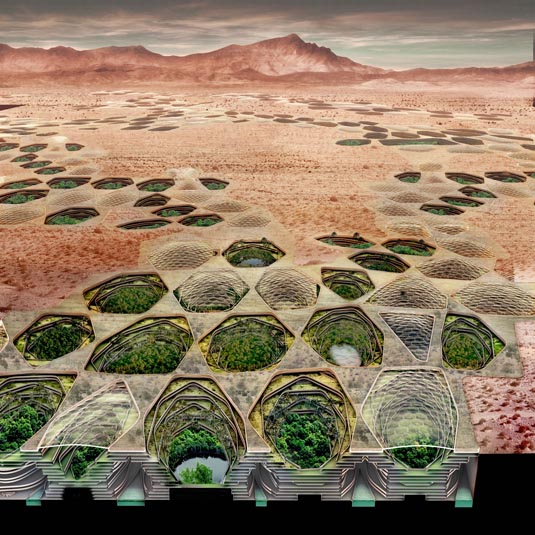

[Image: The weather bowl at Moray, Peru; photo by Ian Wood/Alamy, courtesy of

[Image: The weather bowl at Moray, Peru; photo by Ian Wood/Alamy, courtesy of  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “

[Image: “ 2) For its new

2) For its new  3) The Architectural League wants to give New York the

3) The Architectural League wants to give New York the  4) A new

4) A new  5) The California Architectural Foundation, in partnership with the

5) The California Architectural Foundation, in partnership with the

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by

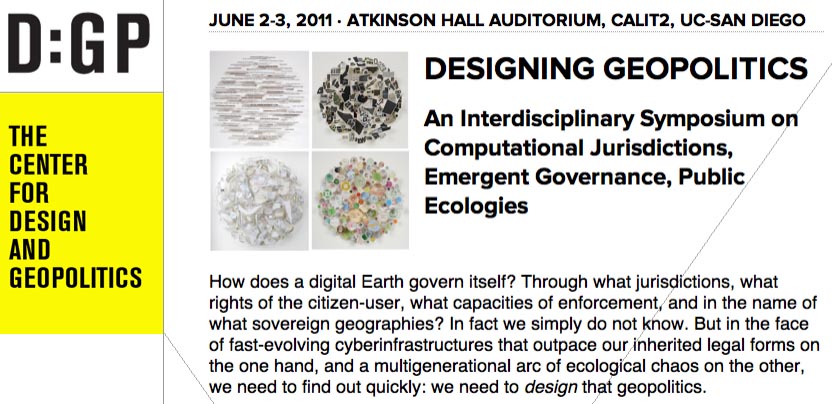

[Image: The “Electric Aurora,” from Specimens of Unnatural History, by  Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on

Finally, Nicola and I will fall out of the car in a state of semi-delirium in La Jolla, California, where I’ll be presenting at a 2-day symposium on

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From