[Image: The Wiederin bookshop in Innsbruck, Austria; photo by Lukas Schaller, courtesy of A10].

[Image: The Wiederin bookshop in Innsbruck, Austria; photo by Lukas Schaller, courtesy of A10].

Barely in time for the holidays, here is a quick look at some of the many new or recent books that have passed through the home office here at BLDGBLOG.

As usual, I have not read all of the books listed here, but this will be pretty clear from the ensuing descriptions; those that I have read, and enjoyed, I will not hesitate to recommend.

And, as always, all of these books are included for the interest of their approach or subject matter as it relates to landscape, spatial sciences, and the built environment more generally.

1) Map of a Nation: A Biography Of The Ordnance Survey by Rachel Hewitt (Granta).

1) Map of a Nation: A Biography Of The Ordnance Survey by Rachel Hewitt (Granta).

2) The Measure of Manhattan: The Tumultuous Career and Surprising Legacy of John Randel, Jr., Cartographer, Surveyor, Inventor by Marguerite Holloway (W.W. Norton).

These two fantastic books form a nice, if coincidental, duo, looking at the early days of scientific cartography and the innovative devices and mathematical techniques that made modern mapping possible. In Rachel Hewitt’s case—a book I found very hard to put down, up reading it till nearly 2am several nights in a row—we trace the origins of the UK’s Ordnance Survey by way of the devices, tools, precision instruments, and imperialist geopolitical initiatives of the time.

Similarly, Marguerite Holloway introduces us to, among many other things, the first measured imposition of the Manhattan grid. I mentioned Holloway’s book the other day here on BLDGBLOG, and am also very happy to have been asked to blurb it. Here’s my description: “This outstanding history of the Manhattan grid offers us a strange archaeology: part spatial adventure, part technical expedition into the heart of measurement itself, starring teams of 19th-century gentlemen striding across the island’s eroded mountains and wild streams, implementing a grid that would soon enough sprout skyscrapers and flatirons, Central Park and 5th Avenue. Marguerite Holloway’s engaging survey takes us step by step through the challenges of obsolete land laws and outdated maps of an earlier metropolis, looking for—and finding—the future shape of this immeasurable city.”

For anyone at all interested in cartography, these make an excellent and intellectually stimulating pair.

3) The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot by Robert Macfarlane (Viking).

3) The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot by Robert Macfarlane (Viking).

4) Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants by Richard Mabey (Ecco).

I’ve spoken highly of Robert Macfarlane’s writing before, and will continue to do so. His Wild Places remains one of my favorite books of the last few years, and I was thus thrilled to hear of his newest: a series of long walks (and a boat ride) through the British landscape, from coastal mudflats to chalk hills and peat bogs, following various kinds of well-worn routes and paths, the “old ways” of his book’s title. Macfarlane’s writing can occasionally strain for rapture when, in fact, it is precisely the mundane—nondescript earthen paths and overlooked back woods—that makes his “journeys on foot” so compelling; but this is an otherwise minor flaw in a highly readable and worthwhile new book.

Meanwhile, Richard Mabey has written an almost impossibly captivating history of weeds, “nature’s most unloved plants.” Covering invasive species, overgrown bomb sites in WWII London, and abandoned buildings, and relating stories from medieval poetry and 21st-century agribusiness to botanical science fiction, Mabey’s book is an awesome sweep through the world of out-of-place plant life.

5) The Maximum of Wilderness: The Jungle in the American Imagination by Kelly Enright (University of Virginia Press).

5) The Maximum of Wilderness: The Jungle in the American Imagination by Kelly Enright (University of Virginia Press).

6) In Search of First Contact: The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo-American Anxiety of Discovery by Annette Kolodny (Duke University Press).

7) The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise by Michael Grunwald (Simon & Schuster).

These three books variously describe encounters with the alien wilderness of a new world. Kelly Enright’s look at “the jungle in American imagination” reads a bit too much like a revised Ph.D. thesis, but its central premise is fascinating, looking not only at the complex differences between the meaning of a jungle and that of a rain forest, but exploring, as she phrases it, “some of the consequences of expanding an American image and ideology of wilderness beyond American shores,” from Theodore Roosevelt to the early days of tropical anthropology.

Annette Kolodny’s review of what can more or less be summarized as the Viking discovery of North America is incredibly rich. Quoting from the cover, Kolodny “offers a radically new interpretation of two medieval Icelandic tales, known as the Vinland Sagas. She contends that they are the first known European narratives about contact with North America.” However, in addition to these tales of “first contact,” Kolodny examines rock carvings in Maine and Canada, as well as Native American folktales, to try to geographically and historically locate the moment when Europeans first arrived in North America, sailing up the small coastal rivers and setting foot on foreign land. Kolodny convincingly demonstrates, in the process, that the Viking discovery of North America was more or less widely accepted by 19th-century historians, but that, she argues, following a large influx of Italian immigrants toward the end of that century and into the 20th, the national importance of Christopher Columbus—an Italian—began to grow. From this emerged, she shows, a kind of narrative contest in which rugged northerners from a stoic, military culture (the Norse) were pitted against royalist Catholic Mediterranean family men as the true cultural progenitors of the United States. It is also interesting here to note that Kolodny assigned these early Icelandic contact narratives to her English literature class, asking students “to consider the possibility that American literature really began in these early ‘contact’ narratives that constructed a so-called New World and its peoples through and for the contemporary cultural understandings of the European imagination.”

I read Michael Grunwald’s The Swamp under particular circumstances—traveling around Florida as part of Venue, along with Smout Allen and a group of students from the Bartlett School of Architecture (photos of that trip can be seen here and here)—which might have added to its appeal. But, either way, I was riveted. Grunwald’s book presents, in effect, all of Florida south of Orlando as a massive series of ecologically misguided—but, from an economic perspective, often highly successful—terraforming projects. Speaking only for myself, the book made it impossible not to notice waterworks everywhere, on all sides and at every scale: every canal, storm sewer, water retention basin, highway overpass, levee, reservoir, drainage ditch, coastal inlet, and flood gate, all parts of an artificially engineered peninsula that wants to—and should—be swamp. Environmentally sensitive without being a screed, and written at the pace of a good New Yorker article, The Swamp was easily one of my favorite discoveries this year, a book I’d place up there with Marc Reisner’s classic Cadillac Desert; it deserves the comparison for, if nothing else, its clear-eyed refocusing of attention onto a region’s hydrology and onto civilization’s larger attempts to manage wild lands (and waters), from the Seminole Wars to George W. Bush. Grunwald also makes clear something that I had barely even considered before, which is that south Florida is actually one of the most recently settled regions of the United States, far younger than the new states of the American West. South Florida, in many senses, is an event that only just recently happened—and Grunwald shows both how and why.

8) Petrochemical America by Richard Misrach and Kate Orff (Aperture Foundation).

8) Petrochemical America by Richard Misrach and Kate Orff (Aperture Foundation).

9) Gateway: Visions for an Urban National Park edited by Alexander Brash, Jamie Hand, and Kate Orff (Princeton Architectural Press/Van Alen Institute).

Here are two new books, each connected to the work of landscape architect and Columbia GSAPP urban planner, Kate Orff.

The first is a split project with photographer Richard Misrach, looking both directly and indirectly at petrochemical infrastructure and the landscapes it passes through in the state of Louisiana. Misrach’s photos open the book with nearly 100 pages’ worth of views into the rapidly transforming nature of Louisiana’s so-called Cancer Alley, “showcasing the immediate plight of embattled local communities and surrounding industries.” Orff’s work follows in the second half of the book with what she calls an “Ecological Atlas” of the same region, mapping what currently exists, more thoroughly annotating Misrach’s photos, and proposing new interventions for ecologically remediating the spoiled landscapes of the region.

The second book is an edited collection of essays and proposals for New York’s Gateway National Recreational Area. Gateway is a strange combination of protected lands and artificial dredgescapes, at the border between ocean and land at the very edge of New York City. Photographs by Laura McPhee join essays by Ethan Carr, Christopher Hawthorne, and others to suggest a new role for parks in American urban life, and a new type of park in general, one that is distributed over discontinuous parcels of marginal land and includes large expanses of active waters.

10) Cities Without Ground: A Hong Kong Guidebook by Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wong (ORO Editions).

10) Cities Without Ground: A Hong Kong Guidebook by Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wong (ORO Editions).

11) Oblique Drawing: A History of Anti-Perspective by Massimo Scolari (MIT Press).

12) Bulwark & Bastion: A Look at Musket Era Fortifications with a Glance at Period Siegecraft by James R. Hinds and Edmund Fitzgerald (Pioneer Press).

13) On the Making of Islands by Nick Sowers (self-published).

Cities Without Ground: A Hong Kong Guidebook was inspired by the revelation that a person can navigate the city of Hong Kong over great distances without ever leaving architecture behind, meandering through complex networks of internal space, from walkways and shopping malls to escalators and covered footbridges. Indeed, one can explore Hong Kong without really setting foot on the surface of the earth at all, making it a “city without ground.” The resulting labyrinthine spatial condition—consisting of “seemingly inescapable and thoroughly disorienting sequences” that cut through, around, between, and under nominally separate megastructures—has led the book’s authors to produce a series of visually dense maps dissecting the various routes a pedestrian can take through the city. A particular highlight comes toward the end, where they focus solely on the city’s air-conditioning, suggesting a kind of thermal cartography of indoor space and implying that temperature control and even humidity are better metrics for evaluating the success of a given project than mere visual or aesthetic concerns.

Massimo Scolari’s Oblique Drawing also pursues the idea that there are other, less well-explored methods for representing the built environment. Although I was disappointed to find that the chapters are, in effect, separate, not always related papers that happen to share a common interest in architectural representation, the book manages to tie together everything from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to the military drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, from medieval Christian landscapes to Chinese painting techniques and the Tower of Babel. Scolari’s book was also mentioned here on the blog last week in the context of architectural espionage.

I was actually given a copy of Bulwark & Bastion while out at the surreal and extremely remote site of Fort Jefferson, in the Dry Tortugas of Florida, and I read it on the 2-hour boat ride back to Key West. No more than a stapled pamphlet, like something you’d make at Kinko’s, it is, nonetheless, an extremely interesting look at built landscapes of warfare and defense. Unsurprisingly, it includes a history of walled cities and forts from Europe; but—and this topic alone deserves a full-length book from a publisher like Princeton Architectural Press—it discusses in detail the landscape defenses of the American Civil War, including massive brick citadels in Alabama, Maryland, South Carolina, and New York City. Star forts, bastions, casements, field works, and other geometries of assault and counter-attack are all illustrated and diagrammed, and they’re followed by a glossary of architectural defensive terms. Thoroughly enjoyable, in particular for anyone interested in military history.

Many of you will know Nick Sowers from his blogging at Archinect, where he explored the niche field of military landscapes and sound recordings. Nick was a deserving recipient of UC-Berkeley’s generous Branner Fellowship, which gave him the resources to travel the world for nearly a year, visiting overseas military bases, old battlefields, and urban fortresses from Japan and the South Pacific to Western Europe, including even the legendary Maunsell Towers in London’s Thames Estuary. At all of these sites, he made field recordings. Nick and I first met, in fact, down in Sydney, Australia, as part of Urban Islands back in 2009. This self-published book tells the story of those travels, including sketches and models from Nick’s own final thesis project at Berkeley, black & white photos from his long circumambulations of closed U.S. bases overseas, and a consistently interesting series of observations on the spatial implications of sound in landscape design. Weird visions of limestone caves being vibrated into existence by the tropical sonic booms of military aircraft give the book a dream-like feel as it comes to a close. Congrats to Nick not only for putting this book together, but for organizing such an interesting, planet-spanning trip in the first place.

14) Architecture for Astronauts: An Activity-based Approach by Sandra Häuplik-Meusburger (Springer Praxis).

14) Architecture for Astronauts: An Activity-based Approach by Sandra Häuplik-Meusburger (Springer Praxis).

15) The Textual Life of Airports: Reading the Culture of Flight by Christopher Schaberg (Continuum).

16) Urban Maps: Instruments of Narrative and Interpretation in the City by Richard Brook and Nick Dunn (Ashgate).

Sandra Häuplik-Meusburger’s Architecture for Astronauts has an accompanying website where we read that a “number of extra-terrestrial habitats have been occupied over the last 40 years of space exploration by varied users over long periods of time. This experience offers a fascinating field to investigate the relationship between the built environment and its users.” Häuplik-Meusburger goes on to definite extra-terrestrial habitat as “the ‘houses and vehicles’ where people live and work beyond Earth: non-planetary habitats such as a spacecraft or space station; and planetary habitats such as a base or vehicle on the Moon or Mars. These building types are set up in environments different from the one on Earth and can be characterized as ‘extreme environments.’ Multiple requirements arise for the architecture and design of such a habitat.” These requirements include different lines of sight, a shifted posture for humans in low-gravity, and different needs for visual clarity and even thermal insulation—a very different architecture, indeed. Her book is thus organized as an activity guide for thinking through things like sleep, food, and hygiene, and how architects can reimagine the spatial requirements of each for the “extreme environments” into which these houses and vehicles might go.

Christopher Schaberg’s Textual Life of Airports looks at the airport as a new kind of cultural space, one with its own emerging literature and its own untold stories, including what he calls “the secret stories of airports—the disturbing, uncomfortable, or smoothed over tales that lie just beneath the surface of these sites.” Citing Marc Augé and ambient music, the “airport screening complex” and Steven Spielberg, his book tries to clarify some of the “spatial ambivalence” travelers feel in an airport’s interconnected spaces. In the context of Häuplik-Meusburger’s book, one wonders what future literatures will emerge for the transitional sites of offworld infrastructure, the spaceports and gravity-free hotels that may or may not be forthcoming for the human future.

For Urban Maps, Richard Brook and Nick Dunn “use the term ‘map’ loosely to describe any form of representation that reveals unseen space, latent conditions or narratives in and of the city.” Their examples come from Google Street View, the photographs of urban explorers, advertisements, contemporary film, surveillance, and the art world, to name but a few.

17) Belgrade, Formal/Informal: A Research on Urban Transformation by ETH Studio Basel Contemporary City Institute (Scheidegger & Spiess).

17) Belgrade, Formal/Informal: A Research on Urban Transformation by ETH Studio Basel Contemporary City Institute (Scheidegger & Spiess).

18) The Waters of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the Baroque City by Katherine Wentworth Rinne (Yale University Press).

Using an awesome font called Warsaw Book/Poster, Belgrade, Formal/Informal zeroes in on “a city that was isolated on the European periphery, a city a long history that was as significant as it was turbulent,” to find what parts of a metropolis with such locally specific circumstances have managed to stay more or less the same, through both war and economic estrangement, and what parts were fundamentally transformed by larger, pan-European events and processes. Further, within this, and as the book’s title suggests, they break the city into formal and informal sectors, the generic and the specific. The book is extensively illustrated, and attractively designed by Ludovic Balland.

Katherine Rinne teaches architecture at the CCA in Oakland, though her online project on the waters of Rome is hosted by the University of Virginia. Her book, The Waters of Rome, coalesces much of that work into a detailed study of the city’s hydrological infrastructures, from the ancient to the nearly modern, with a particular emphasis on the city in its Baroque age. Her approach is “largely topographic,” she explains in the book’s introduction, tying even the innermost fountains and waterworks to the landscapes of hills and rivers outside the city. As she writes, “Rome’s fountains are so dazzling that it is easy for even dedicated to overlook the profound changes that their construction initiated in the social, cultural, and physical life of the city. The transformation was systematic and structural, reaching from ancient springs outside the city walls to include aqueducts, fountains, conduits, drains, sewers, streets, and the Tiber. Because of gravity, which dictated distribution, the water’s flow was constrained or encouraged by the existing topography, which influenced in part how the water was displayed or made available for use, who controlled it and who was served by it, what it cost, and obligations that attached to the people who were allowed to access it.” The book is a vital addition to any syllabus or library on hydraulic urbanism.

19) Foodprint Papers, Volume 1 by Nicola Twilley & Sarah Rich (Foodprint Project).

19) Foodprint Papers, Volume 1 by Nicola Twilley & Sarah Rich (Foodprint Project).

Last not but least, the Foodprint Papers, Volume 1 have been released, edited by Nicola Twilley (my wife) and Sarah Rich, documenting Foodprint NYC from back in 2010, “the first in [a] series of international conversations about food and the city.”

From a cluster analysis of bodega inventories to the cultural impact of the ice-box, and from food deserts to peak phosphorus, panelists examined the hidden corsetry that gives shape to urban foodscapes, and collaboratively speculated on how to feed New York in the future. The free afternoon program included designers, policy-makers, flavor scientists, culinary historians, food retailers, and others, for a wide-ranging discussion of New York’s food systems, past and present, as well as opportunities to transform our edible landscape through technology, architecture, legislation, and education.

The pamphlet is self-published through Lulu, and all purchases help Nicola & Sarah throw more such events in the future. And, while we’re on the subject of food, don’t miss Sarah’s own recent book, Urban Farms.

Happy reading!

All Books Received: August 2015, September 2013, December 2012, June 2012, December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”), May 2010, May 2009, and March 2009.

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: Courtesy of Getty Images/

[Image: Courtesy of Getty Images/ [Image: From

[Image: From

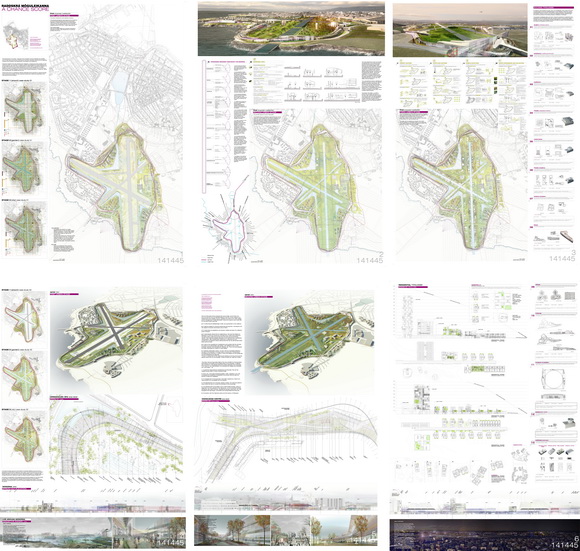

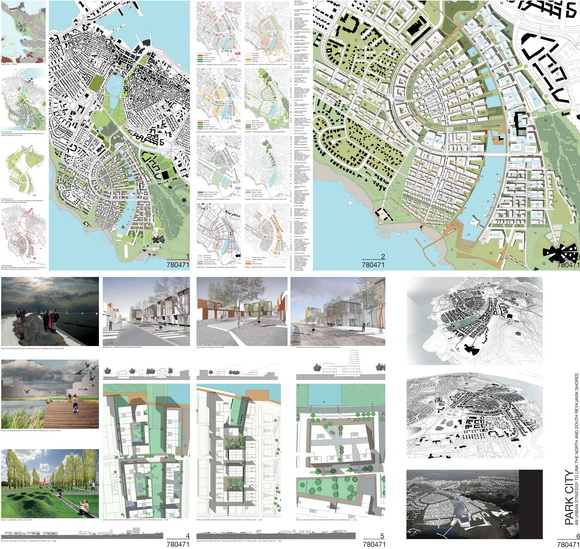

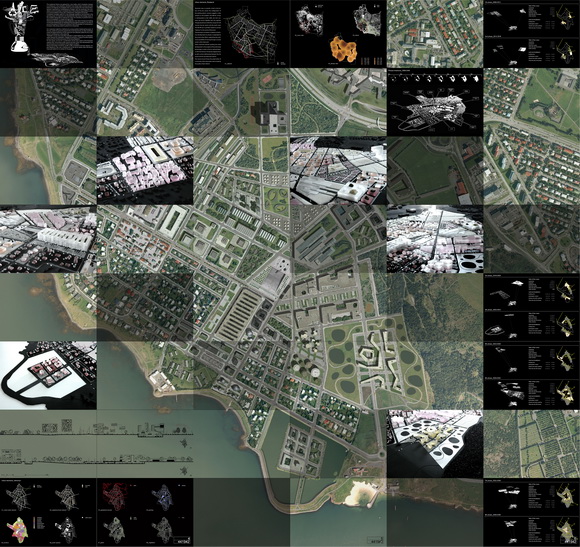

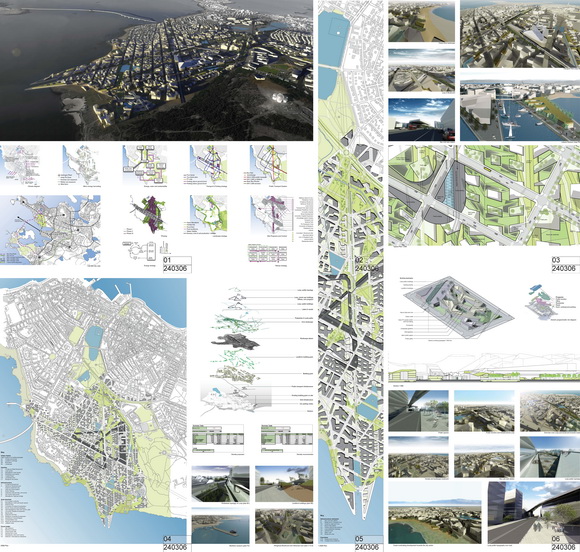

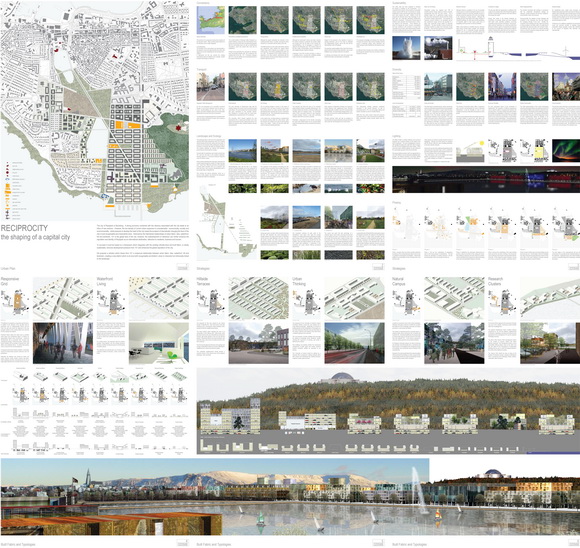

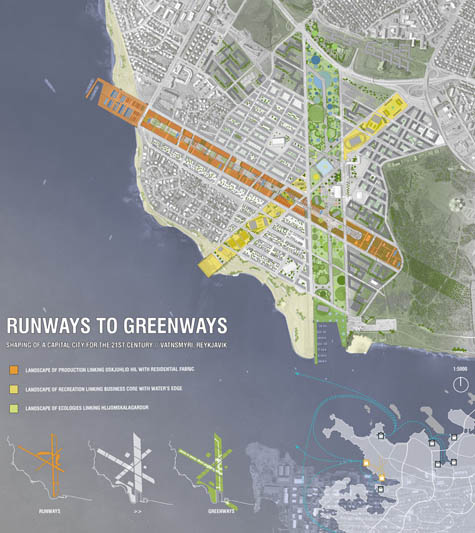

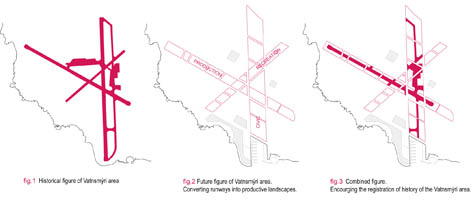

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the  [Image: By

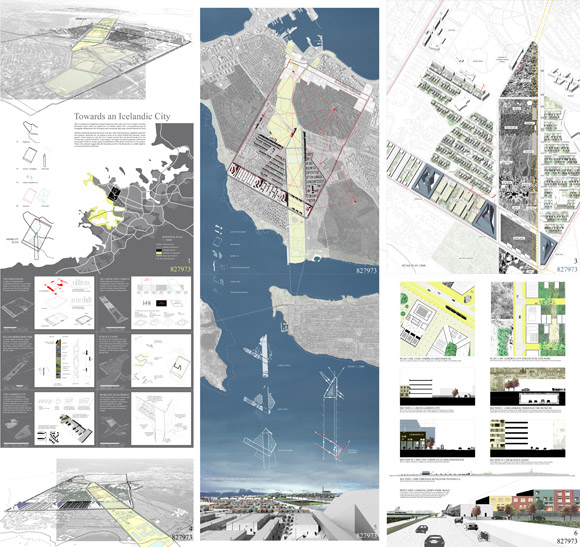

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

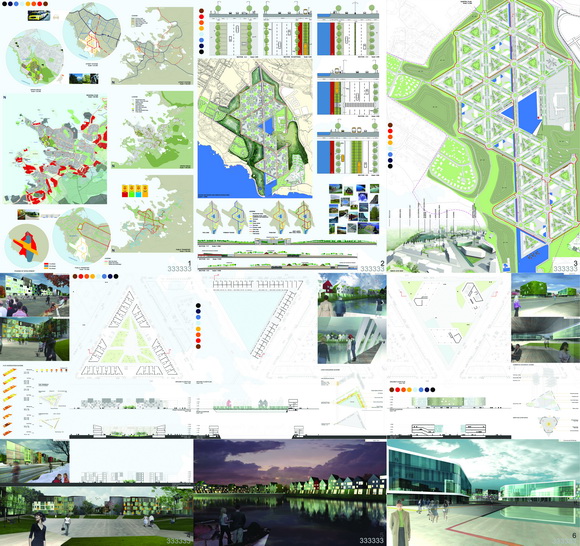

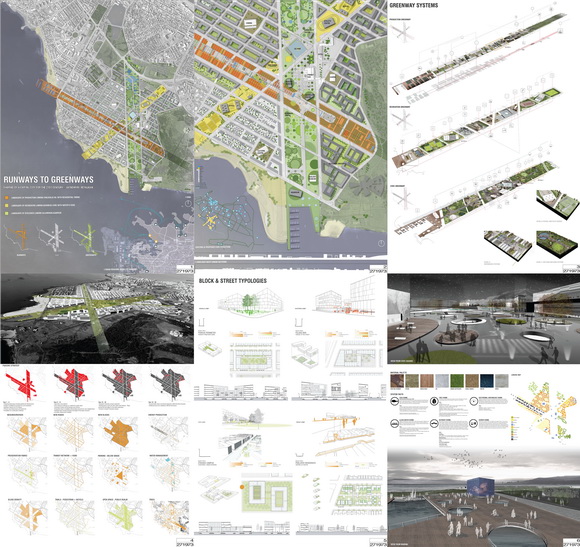

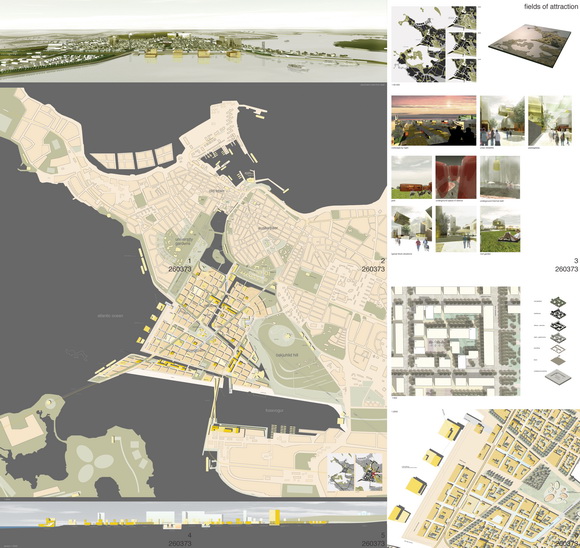

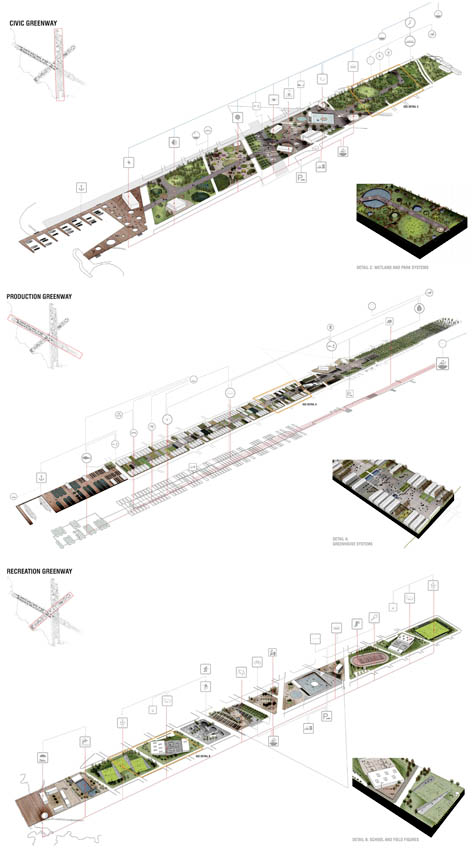

[Images: By

[Images: By

[Images: By

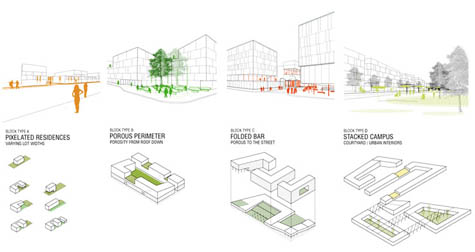

[Images: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By