A landscape painting above Penny Boston’s living room entryway depicts astronauts exploring Mars.

A landscape painting above Penny Boston’s living room entryway depicts astronauts exploring Mars.

Penelope Boston is a speleo-biologist at New Mexico Tech, where she is also Director of Cave and Karst Science. Her work examines subterranean lifeforms, often found very deep within cave systems, including the larger subterranean ecosystems those creatures are connected to. Her research focuses primarily on what are known as extremophiles for their ability to survive in seemingly inhospitable micro-environments here on Earth; these bizarre forms of life, thriving in acidic, anoxic, or highly pressurized situations, offer compelling analogies for the sorts of lifeforms and ecosystems that might exist, undetected, on other planets.

But the flip side of her research are those environments themselves: the caves, tunnels, and other underground spaces inside of which unearthly life might thrive. As you’ll see, this is an interview obsessed with space: how to define space, how space is formed geologically, and what sorts of speculative underground spaces and structures can form under radically different gravitational regimes, deep inside the polar glaciers of distant moons, or even in the turbulent skies of gas giants.

Boston has worked with the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts program (NIAC) to develop protocols for both human extraterrestrial cave habitation and for subterranean life-detection missions on Mars, life which she believes is highly likely to exist.

On a hot summer afternoon, she graciously welcomed me and Nicola Twilley, traveling for our Venue project, into her home in Los Lunas, New Mexico, where we arrived with design futurist Stuart Candy in tow, en route to dropping him off at the Very Large Array later that day.

Over the course of our conversation, Boston told us about her experiences working at Mars analog sites; she explained why she believes there is a strong possibility for life below the surface of the Red Planet, perhaps inside billion-year-old networks of lava tubes; she detailed her own ongoing cave explorations beneath the U.S. Southwest; and we touched on some mind-blowing ideas seemingly straight out of science fiction, including extreme forms of extraterrestrial life (such as dormant life on comets, thawed and reawakened with every passage close to the sun) and the extraordinary potential for developing new pharmaceuticals out of cave microorganisms.

An edited transcript of our conversation appears below.

• • • The Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS) on Devon Island, courtesy of the Mars Society. Geoff Manaugh

The Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS) on Devon Island, courtesy of the Mars Society. Geoff Manaugh: As a graduate student, you co-founded the Mars Underground and then the

Mars Society. You’re a past President of the

Association of Mars Explorers, and you’re also now a member of the science team taking part in

Mars Arctic 365, a new one-year Mars surface simulation mission set to start in summer 2014 on Devon Island. How does this long-term interest in Mars exploration tie into your Earth-based research in speleobiology and subterranean microbial ecosystems?

Penelope Boston: Even though I do study surface things that have a microbial component, like desert varnish and travertines and so forth, I really think that it’s the subsurface of Mars where the greatest chance of extant life, or even preservation of extinct life, would be found.

Nicola Twilley: Is it part of NASA’s strategy to go subsurface at any point, to explore caves on Mars or the moon?

Boston: Well, yes and no. The “Strategy” and the strategy are two different things.

The Mars Curiosity rover is a very capable chemistry and physics machine and I am, of course, dying to hear the details of the geochemistry it samples. A friend of mine, for instance, with whom I’m also a collaborator, is the principal investigator of the SAM instrument. Friends of mine are also on the CheMin instrument. So I have a vested interest, both professionally and personally, in the Curiosity mission.

On the other hand, you know: here we go again with yet another mission on the surface. It’s fascinating, and we still have a lot to learn there, but I hope I will live long enough to see us do subsurface missions on Mars and even on other bodies in the solar system.

Unfortunately, right now, we are sort of in limbo. The downturn in the global economy and our national economy has essentially kicked NASA in the head. It’s very unclear where we are going, at this point. This is having profound, negative effects on the Agency itself and everyone associated with it, including those of us who are external fundees and sort of circum-NASA.

On the other hand, although we don’t have a clear plan, we do have clear interests, and we have been pursuing preliminary studies. NASA has sponsored a number of studies on deep drilling, for example. One of the most famous was probably about 15 years ago, and it really kicked things off. That was up in Santa Fe, and we were looking at different methodologies for getting into the subsurface.

I have done a lot of work, some of which has been NASA-funded, on the whole issue of lava tubes—that is, caves associated with volcanism on the surface. Now, Glenn Cushing and Tim Titus at the USGS facility in Flagstaff have done quite a bit of serious work on the high-res images coming back from Mars, and they have identified lava tubes much more clearly than we ever did in our earlier work over the past decade.

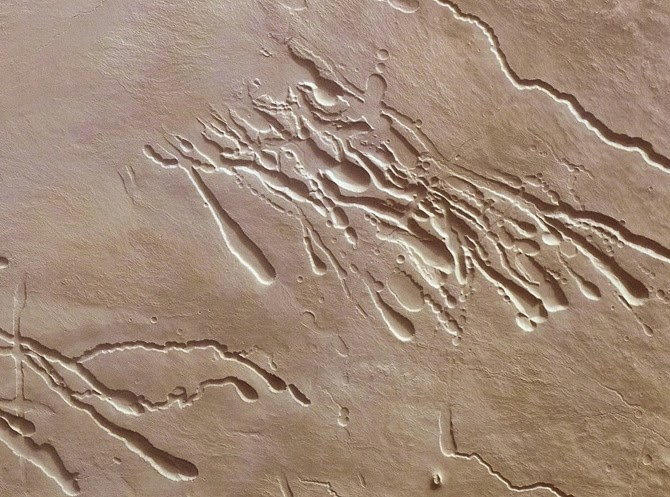

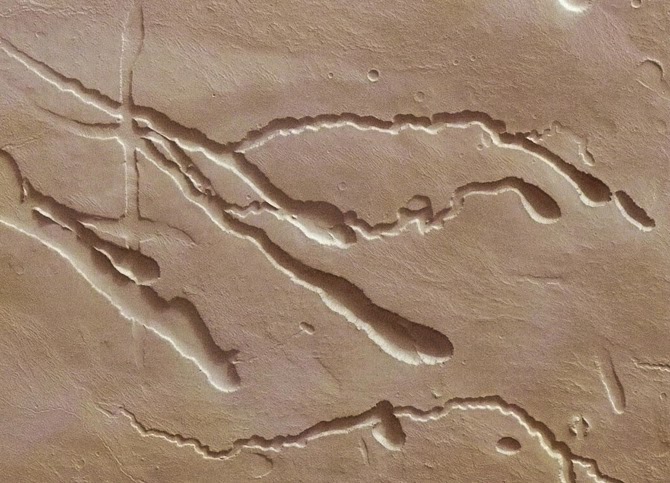

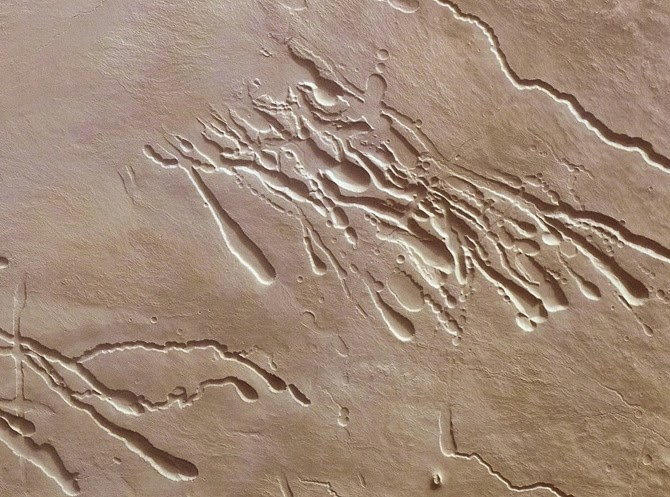

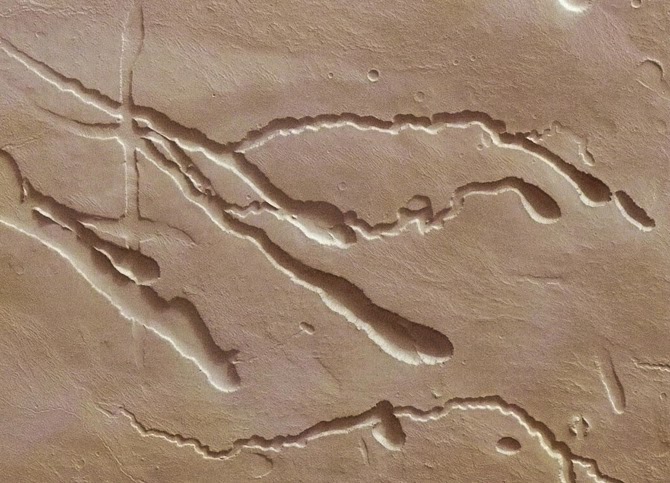

Surface features created by lava tubes on Mars; image via ESA

Surface features created by lava tubes on Mars; image via ESA

Twilley: Is it the expectation that caves as common on Mars as they are on Earth?

Boston: I’d say that lava tubes are large, prominent, and liberally distributed everywhere on Mars. I would guess that there are probably more lava tubes on Mars than there are here on Earth—because here they get destroyed. We have such a geologically and hydro-dynamically active planet that the weathering rates here are enormous.

But on Mars we have a lot of factors that push in the other direction. I’d expect to find tubes of exceeding antiquity—I suspect that billions-of-year-old tubes are quite liberally sprinkled over the planet. That’s because the tectonic regime on Mars is quiescent. There is probably low-level tectonism—there are, undoubtedly, Marsquakes and things like that—but it’s not a rock’n’roll plate tectonics like ours, with continents galloping all over the place, and giant oceans opening up across the planet.

That means the forces that break down lava tubes are probably at least an order of magnitude or more—maybe two, maybe three—less likely to destroy lava tubes over geological time. You will have a lot of caves on Mars, and a lot of those caves will be very old.

Plus, remember that you also have .38 G. The intrinsic tensile strength of the lava itself, or whatever the bedrock is, is also going to allow those tubes to be much more resistant to the weaker gravity there.

Surface features of lava tubes on Mars; images via ESA

Surface features of lava tubes on Mars; images via ESA

Manaugh: I’d imagine that, because the gravity is so much lower, the rocks might also behave differently, forming different types of arches, domes, and other formations underground. For instance, large spans and open spaces would be shaped according to different gravitational strains. Would that be a fair expectation?

Boston: Well, it’s harder to speculate on that because we don’t know what the exact composition of the lava is—which is why, someday, we would love to get a Mars sample-return mission, which is no longer on the books right now. [sighs] It’s been pushed off.

In fact, I just finished, for the seventh time in my career, working on a panel on that whole issue. This was the E2E—or End-to-End—group convened by Dave Beatty, who is head of the Mars Program at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory [PDF].

About a year ago, we finished doing some intensive international work with our European Space Agency partners on Mars sample-return—but now it’s all been pushed off again. The first one of those that I worked on was when I was an undergraduate, almost ready to graduate at Boulder, and that was 1979. It just keeps getting pushed off.

I’d say that we are very frustrated within the planetary and astrobiology communities. We can use all these wonderful instruments that we load onto vehicles like Curiosity and we can send them there. We can do all this fabulous orbital stuff. But, frankly speaking, as a person with at least one foot in Earth science, until you’ve got the stuff in your hands—actual physical samples returned from Mars—there is a lot you can’t do.

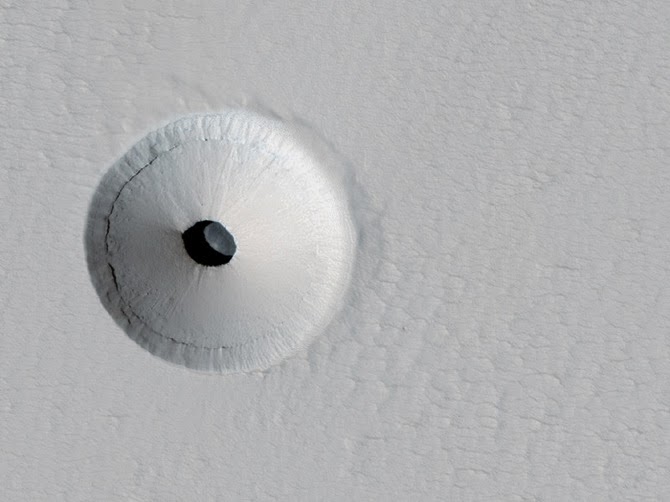

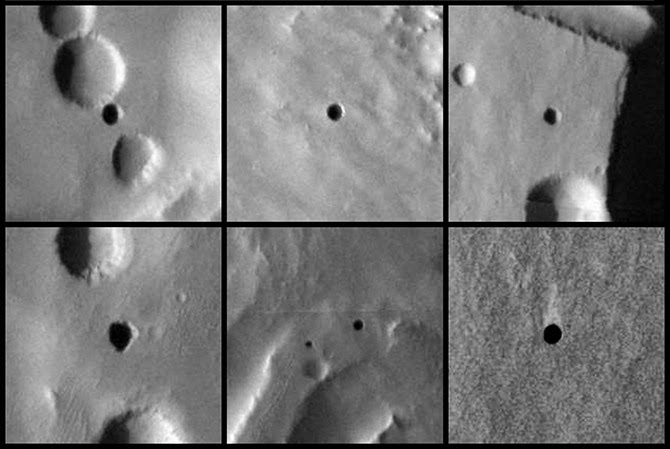

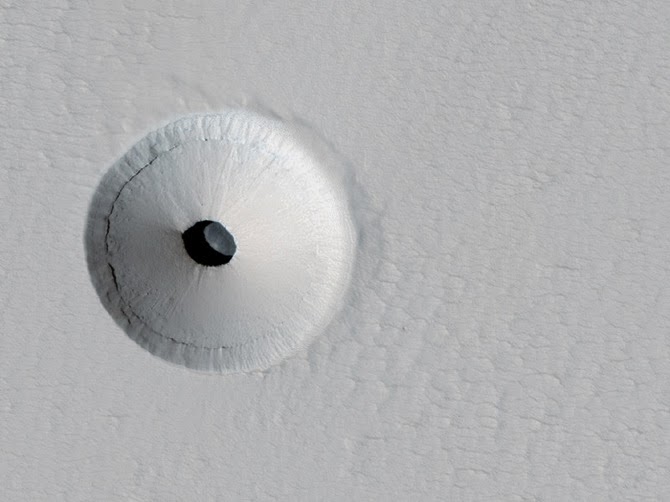

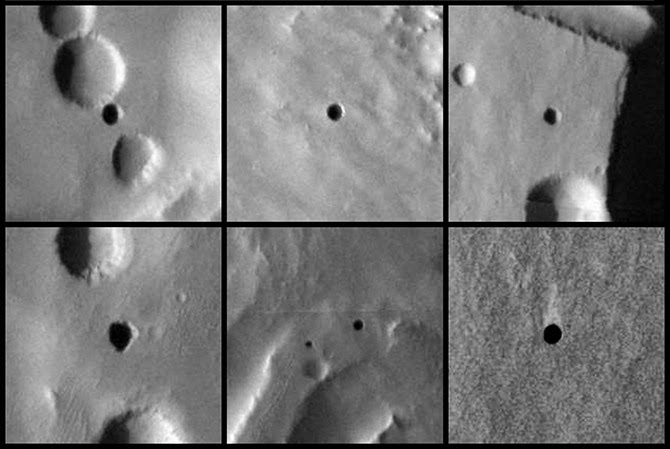

Looking down through a “skylight” on Mars and into a Martian sinkhole; images via NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Looking down through a “skylight” on Mars and into a Martian sinkhole; images via NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Twilley: Could you talk a bit about your work with exoplanetary research, including what you’re looking for and how you might find it?

Boston: [laughs] The two big questions!

But, yes. We are working on a project at Socorro now to atmospherically characterize exoplanets. It’s called NESSI, the New Mexico Exoplanet Spectroscopic Survey Instrument. Our partner is Mark Swain, over at JPL. They are doing it using things like Kepler, and they have a new mission they’re proposing, called FINESSE. FINESSE will be a dedicated exoplanet atmospheric characterizer.

We are also trying to do that, in conjunction with them, but from a ground-based instrument, in order to make it more publicly accessible to students and even to amateur astronomers.

That reminds me—one of the other people you might be interested in talking to is a young woman named Lisa Messeri, who just recently finished her PhD in Anthropology at MIT. She’s at the University of Pennsylvania now. Her focus is on how scientists like me to think about other planets as other worlds, rather than as mere scientific targets—how we bring an abstract scientific goal into the familiar mental space where we also have recognizable concepts of landscape.

I’ve been obsessed with that my entire life: the concept of space, and the human scaling of these vastly scaled phenomena, is central, I think, to my emotional core, not just the intellectual core.

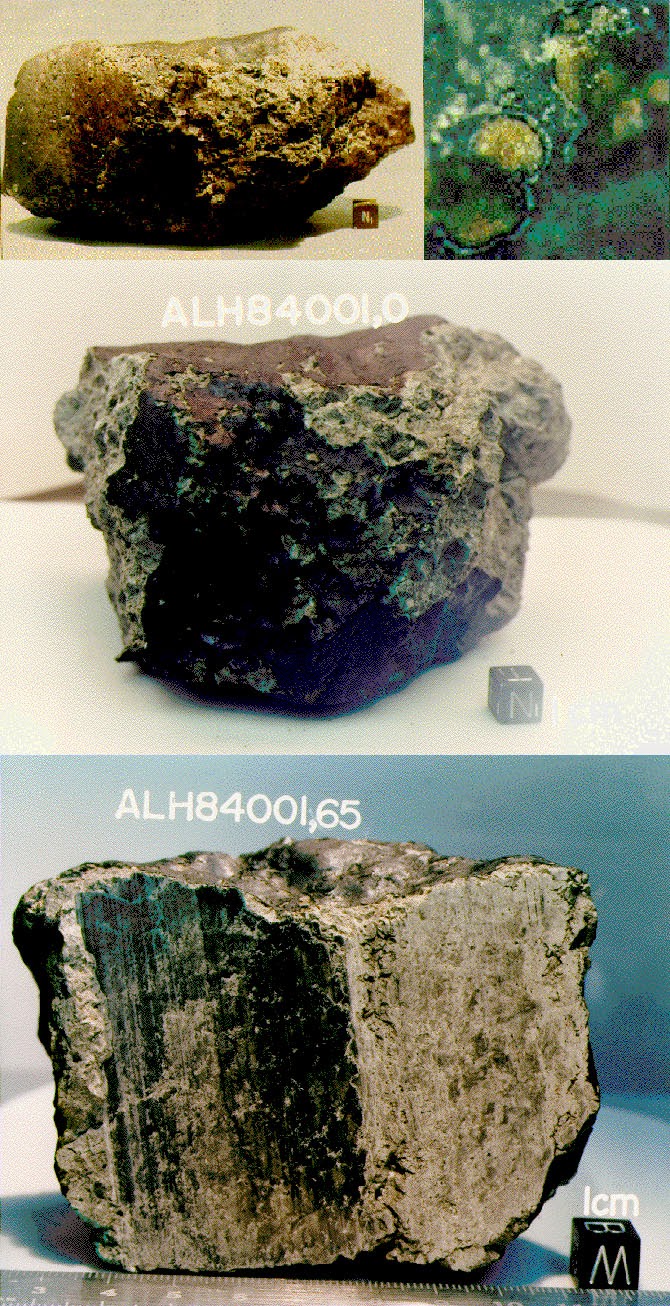

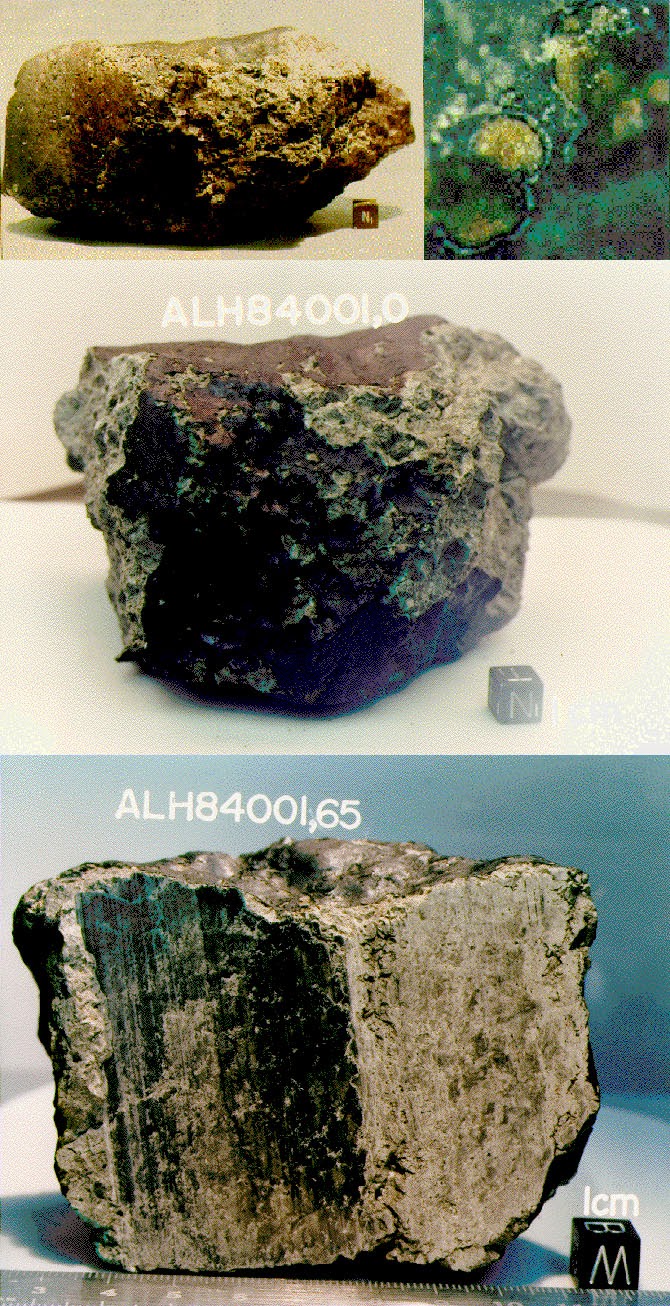

The Allan Hills Meteorite (ALH84001); courtesy of NASA.

The Allan Hills Meteorite (ALH84001); courtesy of NASA.

Manaugh: While we’re on the topic of scale, I’m curious about the idea of astrobiological life inhabiting a radically, undetectably nonhuman scale. For example, one of the things you’ve written and lectured about is the incredible slowness it takes for some organisms to form, metabolize, and articulate themselves in the underground environments you study. Could there be forms of astrobiological life that exist on an unbelievably different timescale, whether it’s a billion-year hibernation cycle that we might discover at just the wrong time and mistake, say, for a mineral? Or might we find something on a very different spatial scale—for example, a species that is more like a network, like an aspen tree or a fungus?

Boston: You know, Paul Davies is very interested in this idea—the concept of a shadow biosphere. Of course, I had also thought about this question for many years, long before I read about Davies or before he gave it a name.

The conundrum you face is: how would you know—how you would study or even conceptualize—these other biospheres? It’s outside of your normal spatial and temporal comfort zone, in which all of your training and experience has guided you to look, and inside of which all of your instruments are designed to function. If it’s outside all of that, how will you know it when you see it?

Imagine comets. With every perihelion passage, volatile gases escape. You are whipping around the solar system. Your body comes to life for that brief period of time only. Now apply that to icy bodies in very elliptical orbits in other solar systems, hosting life with very long periods of dormancy.

There are actually some wonderful early episodes of The Twilight Zone that tap into that theme, in a very poetic and literary way. [laughs] Of course, it’s also the central idea of some of the earliest science fiction; I suppose Gulliver’s Travels is probably the earliest exploration of that concept.

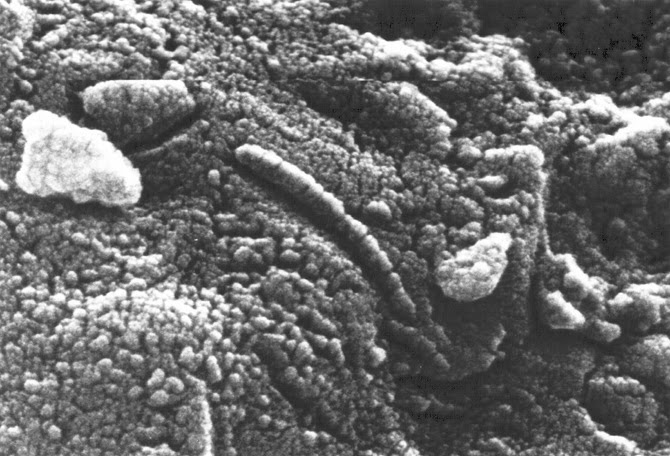

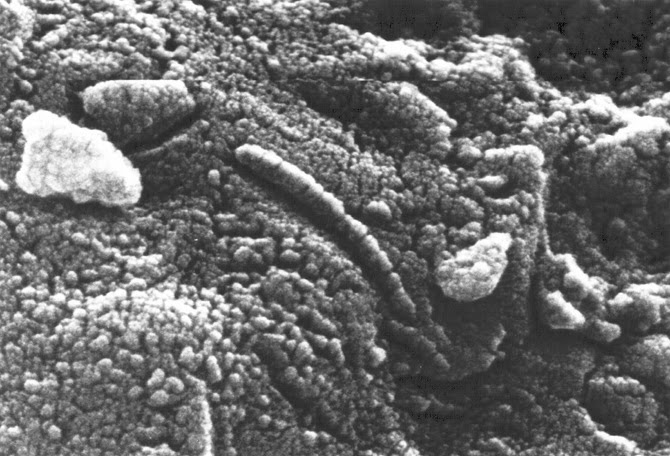

In the microbial realm—to stick with what we do know, and what we can study—we are already dealing with itsy-bitsy, teeny-weeny things that are devilishly difficult to understand. We have a lot of tools now that enable us to approach those, but, very regularly, we’ll see things in electron microscopy that we simply can’t identify and they are very clearly structured. And I don’t think that they are all artifacts of the preparation—things that get put there accidentally during prep.

A lot of the organisms that we actually grow, and with which we work, are clearly nanobacteria. I don’t know how familiar you are with that concept, but it has been extremely controversial. There are many artifacts out there that can mislead us, but we do regularly see organisms that are very small. So how small can they be—what’s the limit?

A few of the early attempts at figuring this out were just childish. That’s a mean thing to say, because a lot of my former mentors have written some of those papers, but they would say things like: “Well, we need to conduct X, Y, and Z metabolic pathways, so, of course, we need all this genetic machinery.” I mean, come on, you know that early cells weren’t like that! The early cells—who knows what they were or what they required?

To take the famous case of the ALH84001 meteorite: are all those little doobobs that you can see in the images actually critters? I don’t know. I think we’ll never know, at least until we go to Mars and bring back stuff.

I have relatively big microbes in my lab that regularly feature little knobs and bobs and little furry things, that I am actually convinced are probably either viruses or prions or something similar. I can’t get a virologist to tell me yes. They are used to looking at viruses that they can isolate in some fashion. I don’t know how to get these little knobby bobs off my guys for them to look at.

The Allan Hills Meteorite (ALH84001); courtesy of NASA.

The Allan Hills Meteorite (ALH84001); courtesy of NASA.

Twilley: In your paper on the human utilization of subsurface extraterrestrial environments [PDF], you discuss the idea of a “Field Guide to Unknown Organisms,” and how to plan to find life when you don’t necessarily know what it looks like. What might go into such a guide?

Boston: The analogy I often use with graduate students when I teach astrobiology is that, in some ways, it’s as if we are scientists on a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri and we are trying to write a field guide to the birds of Earth. Where do you start? Well, you start with whatever template you have. Then you have to deeply analyze every feature of that template and ask whether each feature is really necessary and which are just a happenstance of what can occur.

I think there are fundamental principles. You can’t beat thermodynamics. The need for input and outgoing energy is critical. You have to be delicately poised, so that the chemistry is active enough to produce something that would be a life-like process, but not so active that it outstrips any ability to have cohesion, to actually keep the life process together. Water is great as a solvent for that. It’s probably not the only solvent, but it’s a good one. So you can look for water—but do you really need to look for water?

I think you have to pick apart the fundamental assumptions. I suspect that predation is a relatively universal process. I suspect that parasitism is a universal process. I think that, with the mathematical work being done on complex, evolving systems, you see all these emerging properties.

Now, with all of that said, the details—the sizes, the scale, the pace, getting back to what we were just talking about—I think there is huge variability in there.

Caves on Mars; images courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/USGS.

Caves on Mars; images courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/USGS.

Twilley: How do you train people to look for unrecognizable life?

Boston: I think everybody—all biologists—should take astrobiology. It would smack you on the side of the head and say, “You have to rethink some of these fundamental assumptions! You can’t just coast on them.”

The organisms that we study in the subsurface are so different from the microbes that we have on the surface. They don’t have any predators—so, ecologically, they don’t have to outgrow any predators—and they live in an environment where energy is exceedingly scarce. In that context, why would you bother having a metabolic rate that is as high as some of your compatriots on the surface? You can afford to just hang out for a really long time.

We have recently isolated a lot of strains from these fluid inclusions in the Naica caves—the one with those gigantic crystals. It’s pretty clear that these guys have been trapped in these bubbles between 10,000 and 15,000 years. We’ve got fluid inclusions in even older materials—in materials that are a few million years old, even, in a case we just got some dates for, as much as 40 million years.

Naica Caves, image from the official website. The caves are so hot that explorers have to wear special ice-jackets to survive.

Naica Caves, image from the official website. The caves are so hot that explorers have to wear special ice-jackets to survive.

One of the caveats, of course, is that, when you go down some distance, the overlying lithostatic pressure of all of that rock makes space impossible. Microbes can’t live in zero space. Further, they have to have at least inter-grain spaces or microporosity—there has to be some kind of interconnectivity. If you have organisms completely trapped in tiny pockets, and they never interact, then that doesn’t constitute a biosphere. At some point, you also reach temperatures that are incompatible with life, because of the geothermal gradient. Where exactly that spot is, I don’t know, but I’m actually working on a lot of theoretical ideas to do with that.

In fact, I’m starting a book for MIT Press that will explore some of these ideas. They wanted me to write a book on the cool, weird, difficult, dangerous places I go to and the cool, weird, difficult bugs I find. That’s fine—I’m going to do that. But, really, what I want to do is put what we have been working on for the last thirty years into a theoretical context that doesn’t just apply to Earth but can apply broadly, not only to other planets in our solar system, but to one my other great passions, of course, which is exoplanets—planets outside the solar system.

One of the central questions that I want to explore further in my book, and that I have been writing and talking about a lot, is: what is the long-term geological persistence of organisms and geological materials? I think this is another long-term, evolutionary repository for living organisms—not just fossils—that we have not tapped into before. I think that life gets recycled over significant geological periods of time, even on Earth.

That’s a powerful concept if we then apply it to somewhere like Mars, for example, because Mars does these obliquity swings. It has super-seasonal cycles. It has these little dimpled moons that don’t stabilize it, whereas our moon stabilizes the Earth’s obliquity level. That means that Mars is going through these super cold and dry periods of time, followed by periods of time where it’s probably more clement.

Now, clearly, if organisms can persist for tens of thousands of years—let alone hundreds of thousands of years, and possibly even millions of years—then maybe they are reawakenable. Maybe you have this very different biosphere.

Manaugh: Like a biosphere in waiting.

Boston: Yes—a biosphere in waiting, at a much lower level.

Recently, I have started writing a conceptual paper that really tries to explore those ideas. The genome that we see active on the surface of any planet might be of two types. If you have a planet like Earth, which is photosynthetically driven, you’re going to have a planet that is much more biological in terms of the total amount of biomass and the rates at which this can be produced. But that might not be the only way to run a biosphere.

You might also have a much more low-key biosphere that could actually be driven by geochemical and thermal energy from the inside of the planet. This was the model that we—myself, Chris McKay, and Michael Ivanoff, one of our colleagues from what was the Soviet Union at the time—published more than twenty years ago for Mars. We suggested that there would be chemically reduced gases coming from the interior of the planet.

That 1992 paper was what got us started on caves. I had never been in a wild cave in my life before. We were looking for a way to get into that subsurface space. The Department of Energy was supporting a few investigators, but they weren’t about to share their resources. Drilling is expensive. But caves are just there; you can go inside them.

Penelope Boston caving, image courtesy of V. Hildreth-Werker, from “Extraterrestrial Caves: Science, Habitat, Resources,” NIAC Phase I Study Final Report, 2001.

Penelope Boston caving, image courtesy of V. Hildreth-Werker, from “Extraterrestrial Caves: Science, Habitat, Resources,” NIAC Phase I Study Final Report, 2001.

So that’s really what got us into caving. It was at that point where I discovered caves are so variable and fascinating, and I really refocused my career on that for the last 20 years.

The first time I did any serious caving was actually in Lechuguilla Cave. It was completely nuts to make that one’s first wild cave. We trained for about three hours, then we launched into a five-day expedition into Lechuguilla that nearly killed us! Chris McKay came out with a terrible infection. I had a blob of gypsum in my eye and an infection that swelled it shut. I twisted my ankle. I popped a rib. Larry Lemke had a massive migraine. We were not prepared for this. The people taking us in should have known better. But one of them is a USGS guide and a super caving jock, so it didn’t even occur to him—it didn’t occur to him that we were learning instantaneously to operate in a completely alien landscape with totally inadequate skills.

Lechuguilla Cave, photograph by Dave Bunnell.

Lechuguilla Cave, photograph by Dave Bunnell.

All I knew was that I was beaten to a pulp. I could almost not get across these chasms. I’m a short person. Everybody else was six feet tall. I felt like I was just hanging on long enough so I could get out and live. I’ve been in jams before, including in Antarctica, but that’s all I thought of the whole five days: I just have to live through this.

But, when I got out, I realized that what the other part of my brain had retained was everything I had seen. The bruises faded. My eye stopped being infected. In fact, I got the infection from looking up at the ceiling and having some of those gooey blobs drip down into my eye—but, I was like, “Oh my God. This is biological. I just know it is.” So it was a clue. And, when, I got out, I knew I had to learn how to do this. I wanted to get back in there.

ESA astronauts on a “cave spacewalk” during a 2011 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy of the ESA.

ESA astronauts on a “cave spacewalk” during a 2011 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy of the ESA.

Manaugh: You have spoken about the possibility of entire new types of caves that are not possible on Earth but that might be present elsewhere. What are some of these other cave types you think might exist, and what sort of conditions would be required to form them? You’ve used some great phrases to describe those processes—things like “volatile labyrinths” and “ice volcanism” that create strange cave types that aren’t possible on Earth.

Boston: Well, in terms of ice, I’ll bet there are all sorts of Lake Vostok-like things out there on other moons and planets.

The thing with Lake Vostok is that it’s not a “lake.” It’s a cave: a cave in ice. The ice, in this case, acts as bedrock, so it’s not a lake at all. It’s a closed system.

Manaugh: It’s more like a blister: an enclosed space full of fluid.

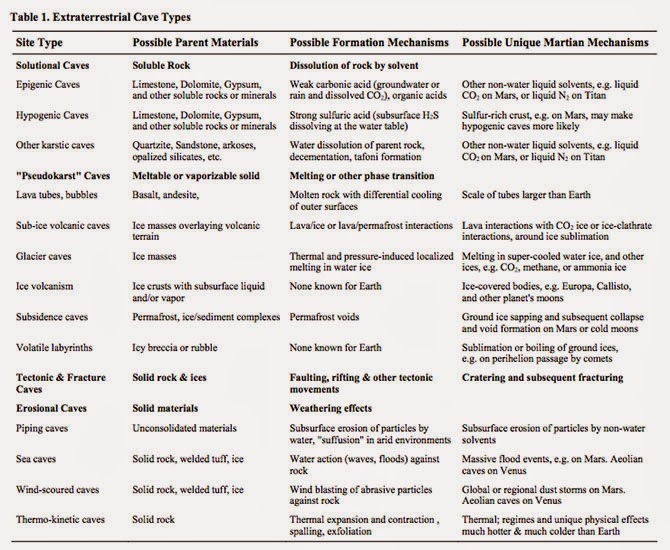

Boston: Exactly. In terms of speculating on the kinds of caves that might exist elsewhere in the universe, we are actually working on a special issue for the Journal of Astrobiology right now, based on the extraterrestrial planetary caves meeting that we did last October. We brought people from all over the place. This is a collaboration between my Institute—the National Cave and Karst Research Institute in Carlsbad, where we have our headquarters—and the Lunar and Planetary Institute.

The meeting was an attempt to explore these ideas. Karl Mitchell from JPL, who I had not met previously, works on Titan; he’s on the Cassini Huygens mission. He thinks he is seeing karst-like features on Titan. Just imagine that! Hydrocarbon fluids producing karst-like features in water-ice bedrock—what could be more exotic than that?

That also shows that the planetary physics dominates in creating these environments. I used to think that the chemistry dominated. I don’t think so anymore. I think that the physics dominates. You have to step away from the chemistry at first and ask: what are the fundamental physics that govern the system? Then you can ask: what are the fundamental chemical potentials that govern the system that could produce life? It’s the same exercise with imagining what kind of caves you can get—and I have a lurid imagination.

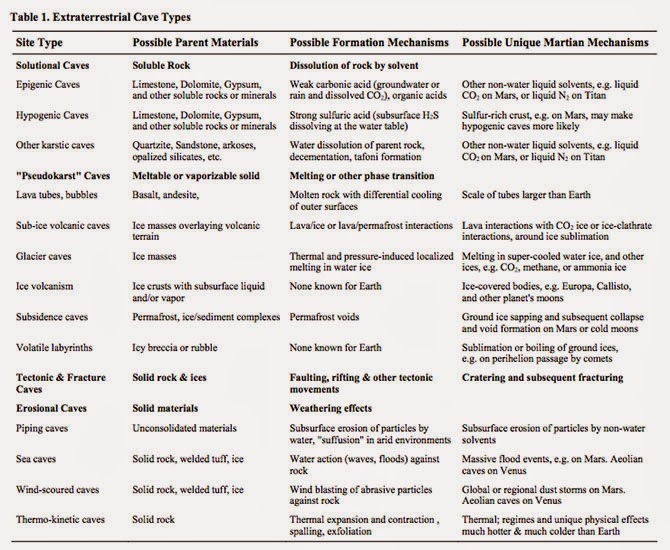

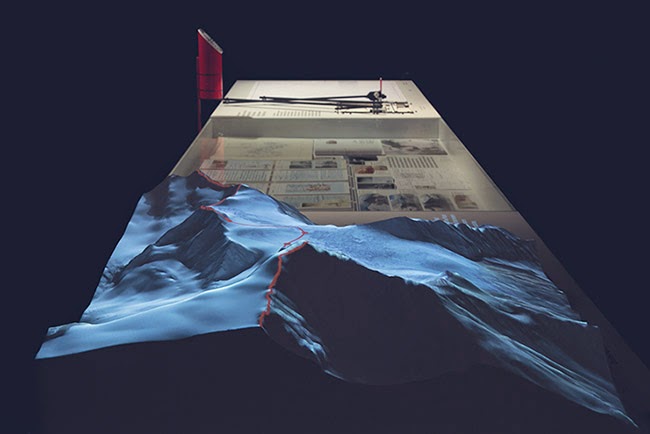

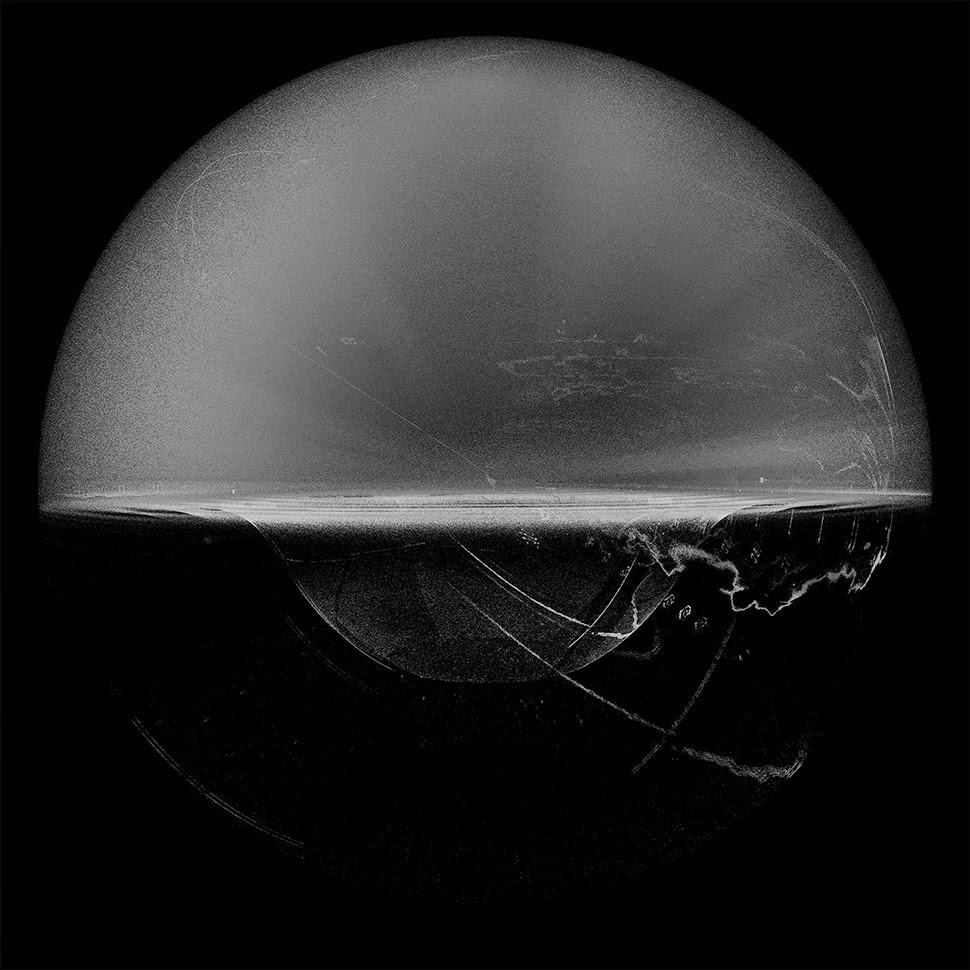

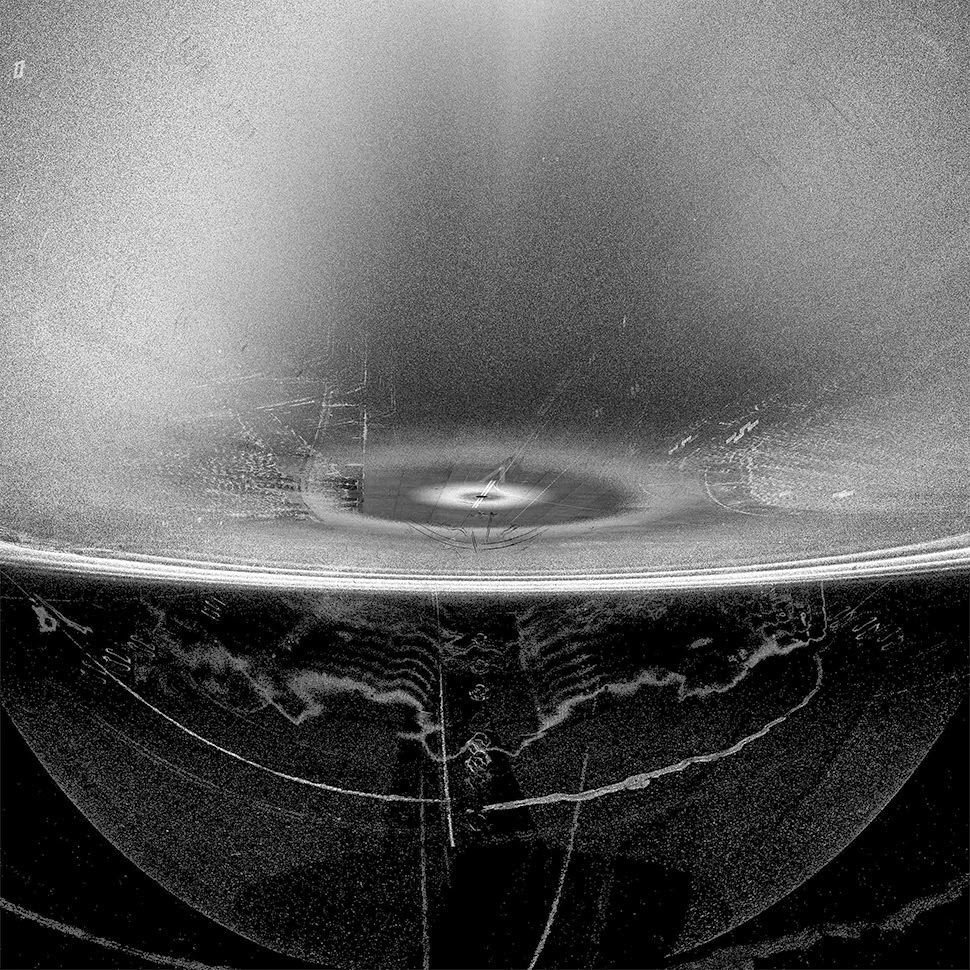

From “Human Utilization of Subsurface Extraterrestrial Environments,” P. J. Boston, R. D. Frederick, S. M. Welch, J. Werker, T. R. Meyer, B. Sprungman, V. Hildreth-Werker, S. L. Thompson, and D. L. Murphy, Gravitational and Space Biology Bulletin 16(2), June 2003.

From “Human Utilization of Subsurface Extraterrestrial Environments,” P. J. Boston, R. D. Frederick, S. M. Welch, J. Werker, T. R. Meyer, B. Sprungman, V. Hildreth-Werker, S. L. Thompson, and D. L. Murphy, Gravitational and Space Biology Bulletin 16(2), June 2003.

One of the fun things I do in my astrobiology class every couple of years is the capstone project. The students break down into groups of four or five, hopefully well-mixed in terms of biologists, engineers, chemists, geologists, physicists, and other backgrounds.

Then they have to design their own solar system, including the fundamental, broad-scale properties of its star. They have to invent a bunch of planets to go around it. And they have to inhabit at least one of those planets with some form of life. Then they have to design a mission—either telescopic or landed—that could study it. They work on this all semester, and they are so creative. It’s wonderful. There is so much value in imagining the biospheres of other planetary bodies.

You just have to think: “What are the governing equations that you have on this planet or in this system?” You look at the gravitational value of a particular body, its temperature regime, and the dominant geochemistry. Does it have an atmosphere? Is it tectonic? One of the very first papers I did—it appeared in one of these obscure NASA special publications, of which they print about 100 and nobody can ever find a copy—was called “Bubbles in the Rocks.” It was entirely devoted to speculation about the properties of natural and artificial caves as life-support structures. A few years later, I published a little encyclopedia article, expanding on it, and I’m now working on another expansion, actually.

I think that, either internally, externally, or both, planetary bodies that form cracks are great places to start. If you have some sort of fluid—even episodically—within that system, then you have a whole new set of cave-forming processes. Then, if you have a material that can exist not only in a solid phase, but also as a liquid or, in some cases, even in a vapor phase on the same planetary body, then you have two more sets of potential cave-forming processes. You just pick it apart from those fundamentals, and keep building things up as you think about these other cave-forming systems and landscapes.

ESA astronauts practice “cavewalking”; image courtesy ESA-V. Corbu.

ESA astronauts practice “cavewalking”; image courtesy ESA-V. Corbu.

Manaugh: One of my favorite quotations is from a William S. Burroughs novel, where he describes what he calls “a vast mineral consciousness at absolute zero, thinking in slow formations of crystal.”

Boston: Oh, wow.

Manaugh: I mention that because I’m curious about how the search for “extraterrestrial life” always tends to be terrestrial, in the sense that it’s geological and it involves solid planetary formations. But what about the search for life on a gaseous planet, for example—would life be utterly different there, chemically speaking, or would it simply be sort of dispersed, or even aerosolized? I suppose I’m also curious if there could be a “cave” on a gaseous planet and, if so, would it really just be a weather system? Is a “cave” on a gaseous planet actually just a storm? Or, to put it more abstractly, can there be caves without geology?

Boston: Hmm. Yes, I think there could be. If it was enclosed or self-perpetuating.

Manaugh: Like a self-perpetuating thermal condition in the sky. It would be a sort of atmospheric “cave.”

Twilley: It would be a bubble.

ESA astronauts explore caves in Sardinia; image courtesy ESA–R. Bresnik.

ESA astronauts explore caves in Sardinia; image courtesy ESA–R. Bresnik.

Boston: In terms of life that could exist in a permanent, fluid medium that was gaseous—rather than a compressed fluid, like water—Carl Sagan and Edwin Salpeter made an attempt at that, back in 1975. In fact, I use their “Jovian Gasbags” paper as a foundational text in my astrobiology classes.

But an atmospheric system like Jupiter is dominated—just like an ocean is—by currents. It’s driven by thermal convection cells, which are the weather system, but it’s at a density that gives it more in common with our oceans than with our sky. And we are already familiar with the fact that our oceans, even though they are a big blob of water, are spatially organized into currents, and they are controlled by density, temperature, and salinity. The ocean has a massively complex three-dimensional structure; so, too, does the Jovian atmosphere. So a gas giant is really more like a gaseous ocean I think.

Now, the interior machinations that go on in inside a planet like Jupiter are driving these gas motions. There is a direct analogy here to the fact that, on our rocky terrestrial planet, which we think of as a solid Earth, the truth is that the mantle is plastic—in fact, the Earth’s lower crust is a very different substance from what we experience up here on this crusty, crunchy top, this thing that we consider solid geology. Whether we’re talking about a gas giant like Jupiter or the mantle of a rocky planet like Earth, we are really just dealing with different regimes of density—and, here again, it’s driven by the physics.

ESA astronauts set up an experimental wind-speed monitoring station in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy ESA/V. Crobu.

ESA astronauts set up an experimental wind-speed monitoring station in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy ESA/V. Crobu.

A couple of years ago, I sat in on a tectonics class that one of my colleagues at New Mexico Tech was giving, which was a lot of fun for me. Everybody else was thinking about Earth, and I was thinking about everything but Earth. For my little presentation in class, what I tried to do was think about analogies to things on icy bodies: to look at Europa, Titan, Enceledus, Ganymede, and so forth, and to see how they are being driven by the same tectonic processes, producing the same kind of brittle-to-ductile mantle transition, but in ice rather than rock.

I think that, as we go further and further in the direction of having to explain what we think is going on in exoplanets, it’s going to push some of the geophysics in that direction, as well. There is amazingly little out there. I was stunned, because I know a lot of planetary scientists who are thinking about this kind of stuff, but there is a big gulf between Earth geophysics and applying those lessons to exoplanets.

ESA astronauts prepare for their 2013 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy ESA-V. Crobu.

ESA astronauts prepare for their 2013 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy ESA-V. Crobu.

Manaugh: We need classes in speculative geophysics.

Boston: Yeah—come on, geophysicists! [laughs] Why shouldn’t they get in the game? We’ve been doing it in astrobiology for a long time.

In fact, when I’ve asked my colleagues certain questions like, “Would we even get orogeny on a three Earth-mass planet?” They are like, “Um… We don’t know.” But you know what? I bet we have the equations to figure that out.

It starts with something as simple as that: in different or more extreme gravitational regimes, could you have mountains? Could you have caves? How could you calculate that? I don’t know the answer to that—but you have to ask it.

ESA astronauts take microbiological samples during a 2011 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy of the ESA.

ESA astronauts take microbiological samples during a 2011 training mission in the caves of Sardinia; image courtesy of the ESA.

Twilley: You’re a member of NASA’s Planetary Protection Subcommittee. Could you talk a little about what that means? I’m curious whether the same sorts of planetary protection protocols we might use on other planets, like Mars, should also be applied to the Earth’s subsurface. How do we protect these deeper ecosystems? How do we protect deeper ecosystems on Mars, assuming there are any?

Boston: That’s a great question. We are working extremely hard to do that, actually.

Planetary protection is the idea that we must protect Earth from off-world contaminants. And, of course, vice versa: we don’t want to contaminate other planets—both for scientific reasons and, at least in my case, for ethical reasons—with biological material from Earth.

In other words, I think we owe it to our fellow bodies in the solar system to give them a chance to prove their biogenicity or not, before humans start casually shedding our skin cells or transporting microbes there.

That’s planetary protection, and it works both ways.

One thing I have used as a sales pitch in some of my proposals is the idea that we are attempting to become more and more noninvasive in our cave exploration, which is very hard to do. For example, we have pushed all of our methods in the direction of using miniscule quantities of sample. Most Earth scientists can just go out and collect huge chunks of rock. Most biologists do that, too. You grow E. coli in the lab and you harvest tons of it. But I have to take just a couple grams of material—on a lucky day—sometimes even just milligrams of material, with very sparse bio density in there. I have to work with that.

What this means is that the work we are doing also lends itself really well to developing methods that would be useful on extraterrestrial missions.

In fact, we are pushing in the direction of not sampling at all, if we can. We are trying to see what we can learn about something before we even poke it. So, in our terrestrial caving work, we are actually living the planetary protection protocol.

We are also working in tremendously sensitive wilderness areas and we are often privileged enough to be the only people to get in there. We want to minimize the potential contamination.

That said, of course, we are contaminant sources. We risk changing the environment we’re trying to study. We struggle with this. I struggle with it physically and methodologically. I struggle with it ethically. You don’t want to screw up your science and inadvertently test your own skin bugs.

I’d say this is one of those cases where it’s not unacceptable to have a nonzero risk—to use a double negative again. There are few things in life that I would say that about. Even in our ridiculous risk-averse culture, we understand that for most things, there is a nonzero risk of basically anything. There is a nonzero risk that we’ll be hit by a meteorite now, before we are even done with this interview. But it’s pretty unlikely.

In this case, I think it’s completely unacceptable to run much of a risk at all.

That said, the truth is that pathogens co-evolve with their hosts. Pathogenesis is a very delicately poised ecological relationship, much more so than predation. If you are made out of the same biochemistry I’m made of, the chances are good that I can probably eat you, assuming that I have the capability of doing that. But the chances that I, as a pathogen, could infect you are miniscule. So there are different degrees of danger.

There is also the alien effect, which is well known in microbiology. That is that there is a certain dose of microbes that you typically need to get in order for them to take hold, because they are coming into an area where there’s not much ecological space. They either have to be highly pre-adapted for whatever the environment is that they land in, or they have to be sufficiently numerous so that, when they do get introduced, they can actually get a toehold.

We don’t really understand some of the fine points of how that occurs. Maybe it’s quorum sensing. Maybe it’s because organisms don’t really exist as single strains at the microbial level and they really have to be in consortia—in communities—to take care of all of the functions of the whole community.

We have a very skewed view of microbiology, because our knowledge comes from a medical and pathogenesis history, where we focus on single strains. But nobody lives like that. There are no organisms that do that. The complexity of the communal nature of microorganisms may be responsible for the alien effect.

So, given all of that, do I think that we are likely to be able to contaminate Mars? Honestly, no. On the surface, no. Do I act as if we can? Yes—absolutely, because the stakes are too high.

Now, do I think we could contaminate the subsurface? Yes. You are out of the high ultraviolet light and out of the ionizing radiation zone. You would be in an environment much more likely to have liquid water, and much more likely to be in a thermal regime that was compatible with Earth life.

So you also have to ask what part of Mars you are worried about contaminating.

ESA teams perform bacterial sampling and examine a freshwater supply; top photo courtesy ESA–V. Crobu; bottom courtesy ESA/T. Peake.

ESA teams perform bacterial sampling and examine a freshwater supply; top photo courtesy ESA–V. Crobu; bottom courtesy ESA/T. Peake.

Manaugh: There’s been some interesting research into the possibility of developing new pharmaceuticals from these subterranean biospheres—or even developing new industrial materials, like new adhesives. I’d love to know more about your research into speleo-pharmacology or speleo-antibiotics—drugs developed from underground microbes.

Boston: It’s just waiting to be exploited. The reasons that it has not yet been done have nothing to do with science and nothing to do with the tremendous potential of these ecosystems, and everything to do with the bizarre and not very healthy economics of the global drug industry. In fact, I just heard that someone I know is leaving the pharmaceutical industry, because he can’t stand it anymore, and he’s actually going in the direction of astrobiology.

Really, there is a de-emphasis on drug discovery today and more of an emphasis on drug packaging. It is entirely profit-driven motive, which is distasteful, I think, and extremely sad. I see a real niche here for someone who doesn’t want to become just a cog in a giant pharmaceutical company, someone who wants to do a small start-up and actually do drug discovery in an environment that is astonishingly promising.

It’s not my bag; I don’t want to develop drugs. But I see our organisms producing antibiotics all the time. When we grow them in culture, I can see where some of them are oozing stuff—pink stuff and yellow stuff and clear stuff. And you can see it in nature. If you go to a lava tube cave, here in New Mexico, you see they are doing it all the time.

A lot of these chemistry tests screen for mutagenic activity, chemogenic activity, and all of the other things that are indications of cancer-fighting drugs and so on, and we have orders of magnitude more hits from cave stuff than we do from soils. So where is everybody looking? In soils. Dudes! I’ve got whole ecosystems in one pool that are different from an ecosystem in another pool that are less than a hundred feet apart in Lechuguilla Cave! The variability—the non-homogeneity of the subsurface—vastly exceeds the surface, because it’s not well mixed.

ESA astronauts prepare their experiments and gear for a 2013 CAVES (“Cooperative Adventure for Valuing and Exercising human behaviour and performance Skills”) mission in Sardinia; image courtesy ESA–V. Crobu

ESA astronauts prepare their experiments and gear for a 2013 CAVES (“Cooperative Adventure for Valuing and Exercising human behaviour and performance Skills”) mission in Sardinia; image courtesy ESA–V. Crobu

Twilley: In your TED talk, you actually say that the biodiversity in caves on Earth may well exceed the entire terrestrial biosphere.

Boston: Oh, yes—certainly the subsurface. There is a heck of a lot of real estate down there, when you add all those rock-fracture surface areas up. And each one of these little pockets is going off on its own evolutionary track. So the total diversity scales with that. It’s astonishing to me that speleo-bioprospecting hasn’t taken off already. I keep writing about it, because I can’t believe that there aren’t twenty-somethings out there who don’t want to go work for big pharma, who are fascinated by this potential for human use.

There is a young faculty member at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, whose graduate student is one of our friends and cavers, and they are starting to look at some of these. I’m like, “Go for it! I can supply you with endless cultures.”

Twilley: In your “Human Mission to Inner Space” experiment, you trialed several possible Martian cave habitat technologies in a one-week mission to a closed cave with a poisonous atmosphere in Arizona. As part of that, you looked into Martian agriculture, and grew what you called “flat crops.” What were they?

Boston: We grew great duckweed and waterfern. We made duckweed cookies. Gus made a rice and duckweed dish. It was quite tasty. [laughs] We actually fed two mice on it exclusively for a trial period, but although duckweed has more protein than soybeans, there weren’t enough carbohydrates to sustain them calorically.

But the duckweed idea was really just to prove a point. A great deal of NASA’s agricultural research has been devoted to trying to grow things for astronauts to make them happier on the long, outbound trips—which is very important. It is a very alien environment and I think people underestimate that. People who have not been in really difficult field circumstances have no apparent understanding of the profound impact of habitat on the human psyche and our ability to perform. Those of us who have lived in mock Mars habitats, or who have gone into places like caves, or even just people who have traveled a lot, outside of their comfort zone, know that. Your circumstances affect you.

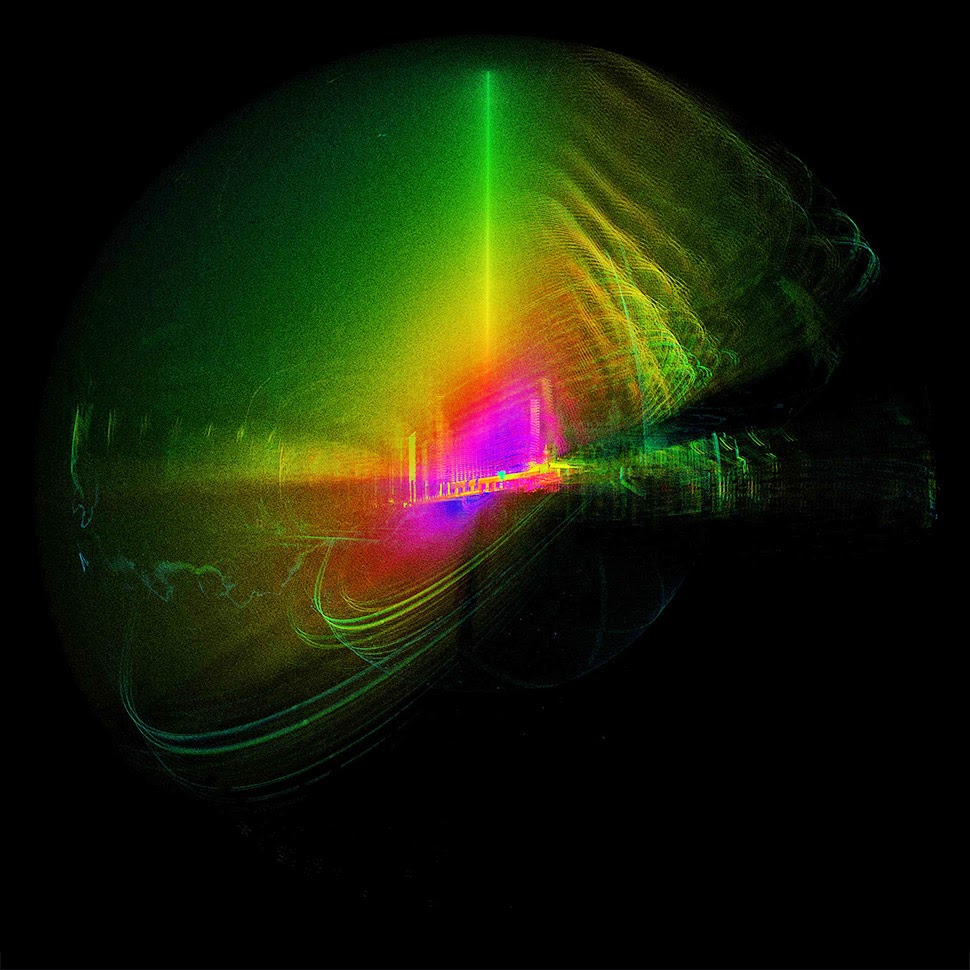

One of the things we designed, for example, was a way to illuminate an interior subsurface space by projecting a light through fluid systems—because you’d do two things. You’d get photosynthetic activity of these crops, but you’d also get a significant amount of very soothing light into the interior space.

We had such a fabulous time doing that project. We just ran with the idea of: what you can do to make the space that a planet has provided for you into actual, livable space.

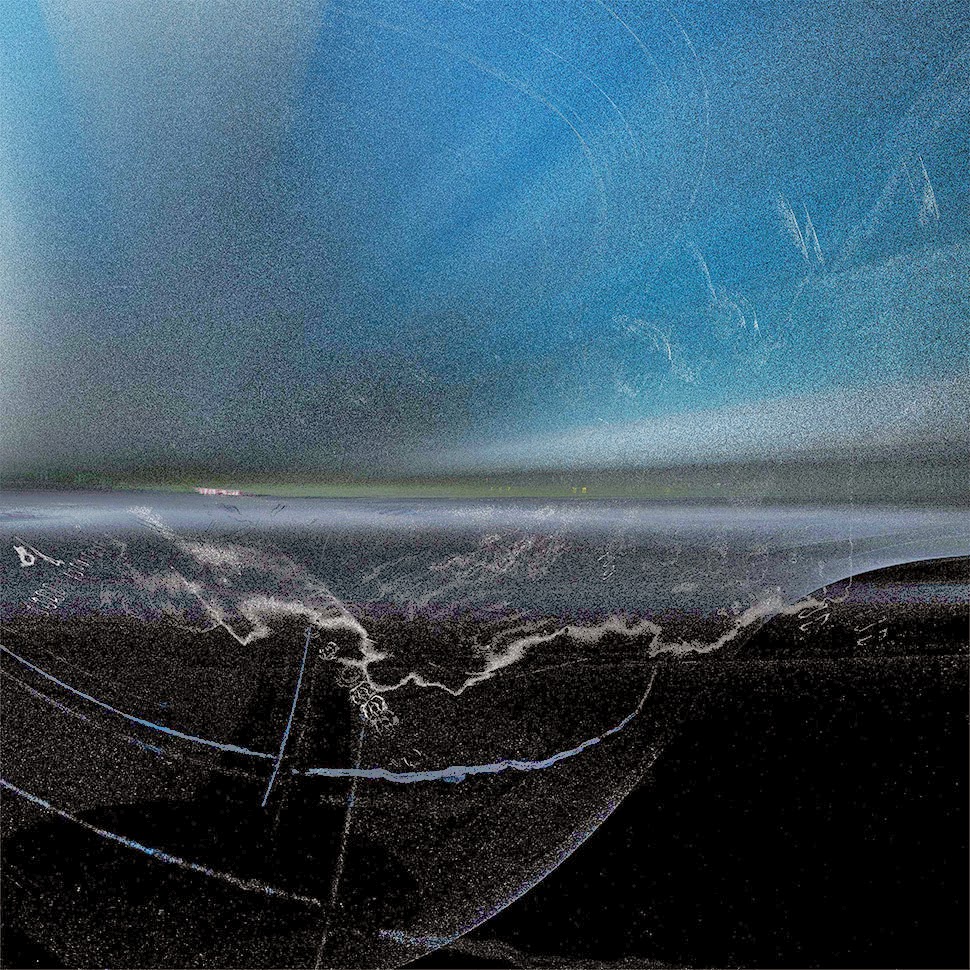

From Boston’s presentation report on the Human Utilization of Subsurface Extraterrestrial Environments, NIAC Phase II study (PDF).

From Boston’s presentation report on the Human Utilization of Subsurface Extraterrestrial Environments, NIAC Phase II study (PDF).

Twilley: Earlier on our Venue travels, we actually drove through Hanksville, Utah, where many of the Mars analog environment studies are done.

Boston: I’ve actually done two crews there. It’s incredibly effective, considering how low-fidelity it is.

Twilley: What makes it so effective?

Boston: Simple things are the most critical. The fact that you have to don a spacesuit and the incredible cumbersomeness of that—how it restricts your physical space in everything from how you turn your head to how your visual field is limited. Turning your head doesn’t work anymore, because you just look inside your helmet; your whole body has to turn, and it can feel very claustrophobic.

Then there are the gloves, where you’ve got your astronaut gloves on and you’re trying to manipulate the external environment without your normal dexterity. And there’s the cumbersomeness and, really, the psychological burden of having to simulate going through an airlock cycle. It’s tremendously effective. Being constrained with the same group of people, it is surprisingly easy to buy into the simulation. It’s not as if you don’t know you’re not on Mars, but it doesn’t take much to make a convincing simulation if you get those details right.

The Mars Desert Research Station, Hanksville, Utah; image courtesy of bandgirl807/Wikipedia.

The Mars Desert Research Station, Hanksville, Utah; image courtesy of bandgirl807/Wikipedia.

I guess that’s what was really surprising to me, the first time I did it: how little it took to be transform your human experience and to really cause you to rethink what you have to do. Because everything is a gigantic pain in the butt. Everything you know is wrong. Everything you think in advance that you can cope with fails in the field. It is a humbling experience, and an antidote to hubris. I would like to take every engineer I know that works on space stuff—

Twilley: —and put them in Hanksville! [laughter]

Boston: Yes—seriously! I have sort of done that, by taking these loafer-wearing engineers—most of whom are not outdoorsy people in any way, who haunt the halls of MIT and have absorbed the universe as a built environment—out to something as simple as the lava tubes. I could not believe how hard it was for them. Lava tubes are not exactly rigorous caving. Most of these are walk-in, with only a little bit of scrambling, but you would have thought we’d just landed on Mars. It was amazing for some of them, how totally urban they are and how little experience they have of coping with a natural space. I was amazed.

I actually took a journalist out to a lava tube one time. I think this lady had never left her house before! There’s a little bit of a rigorous walk over the rocks—but it was as if she had never walked on anything that was not flat before.

From Venue’s own visit to a lava tube outside Flagstaff, AZ.

From Venue’s own visit to a lava tube outside Flagstaff, AZ.

It’s just amazing what one’s human experience does. This is why I think engineers should be forced to go out into nature and see if the systems they are designing can actually work. It’s one of the best ways for them to challenge their assumptions, and even to change the types of questions they might be asking in the first place.

(This interview was previously published on Venue).

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via Der Spiegel].

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via Der Spiegel]. [Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via Der Spiegel].

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via Der Spiegel].

[Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via  [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via  [Image: The abandoned streets of

[Image: The abandoned streets of  [Image: Midland, California, via

[Image: Midland, California, via

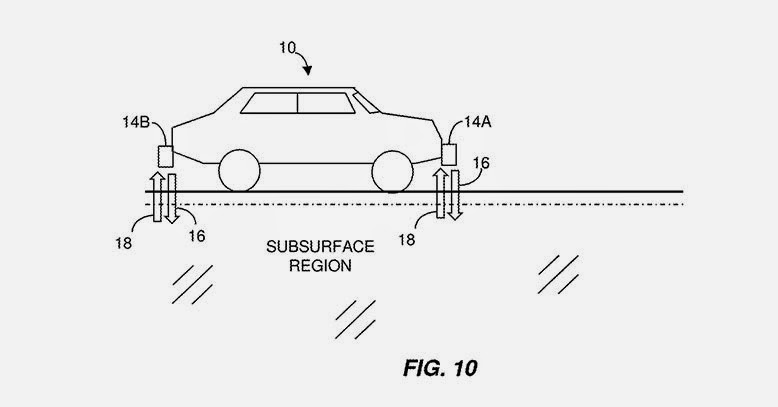

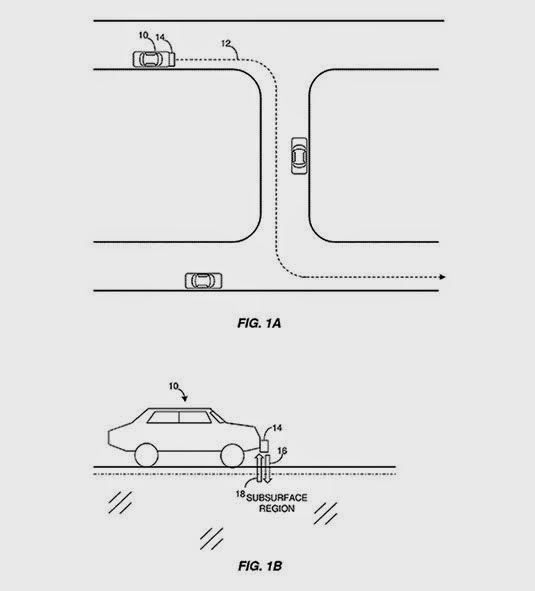

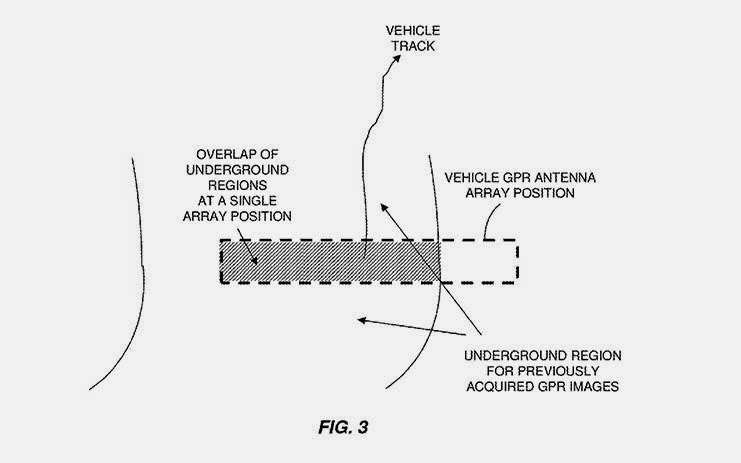

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy  [Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy  [Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: From a patent filed by MIT, courtesy

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

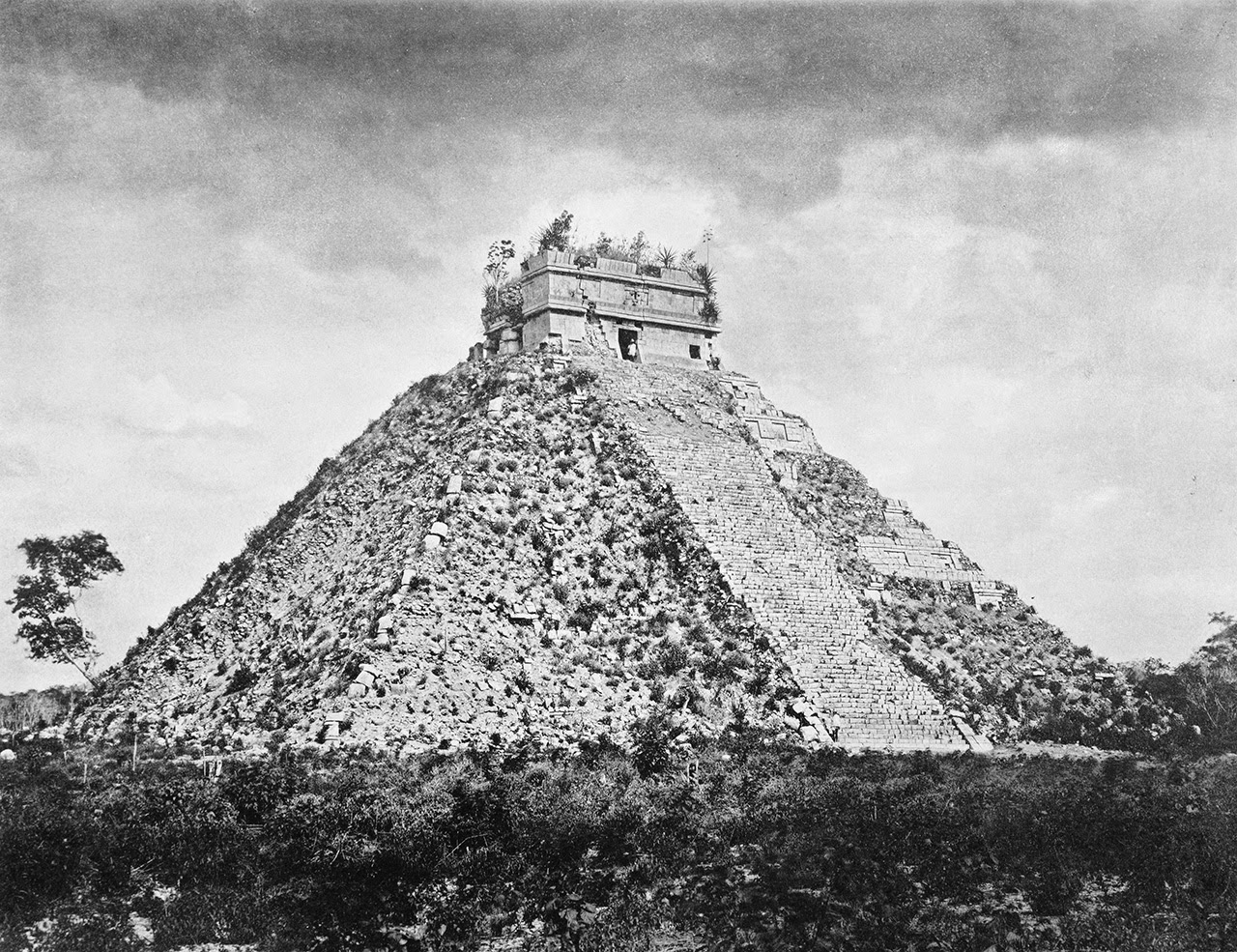

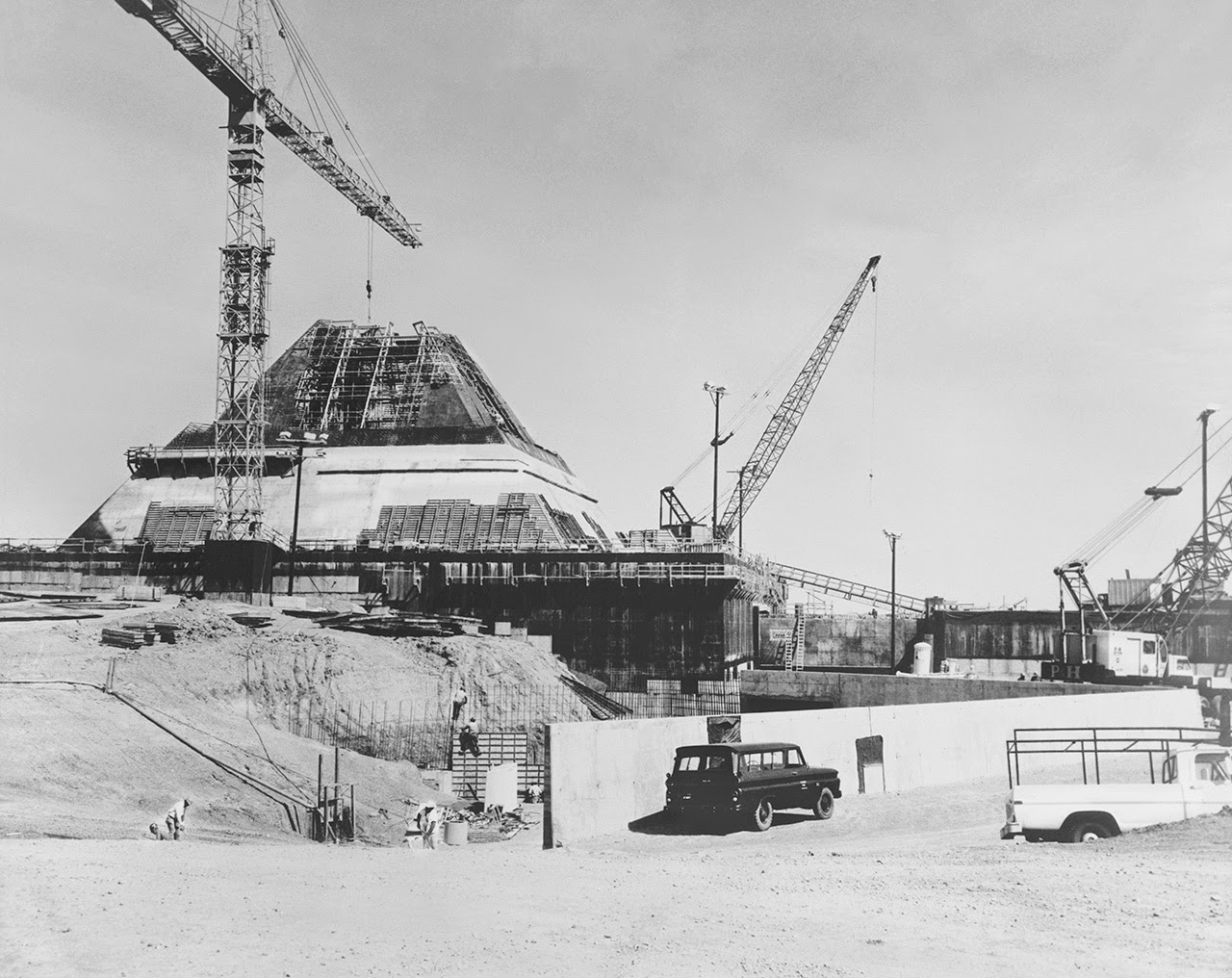

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

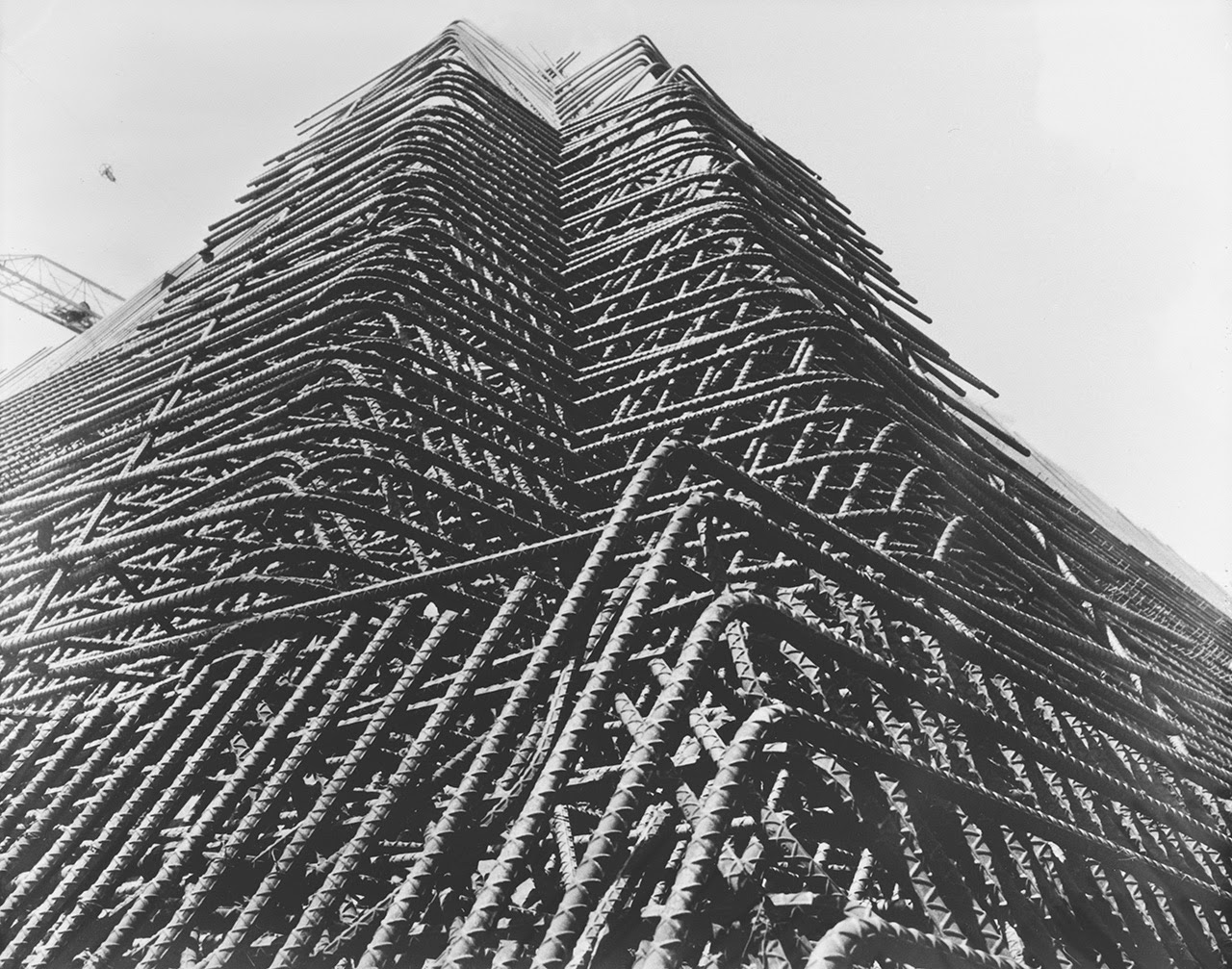

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

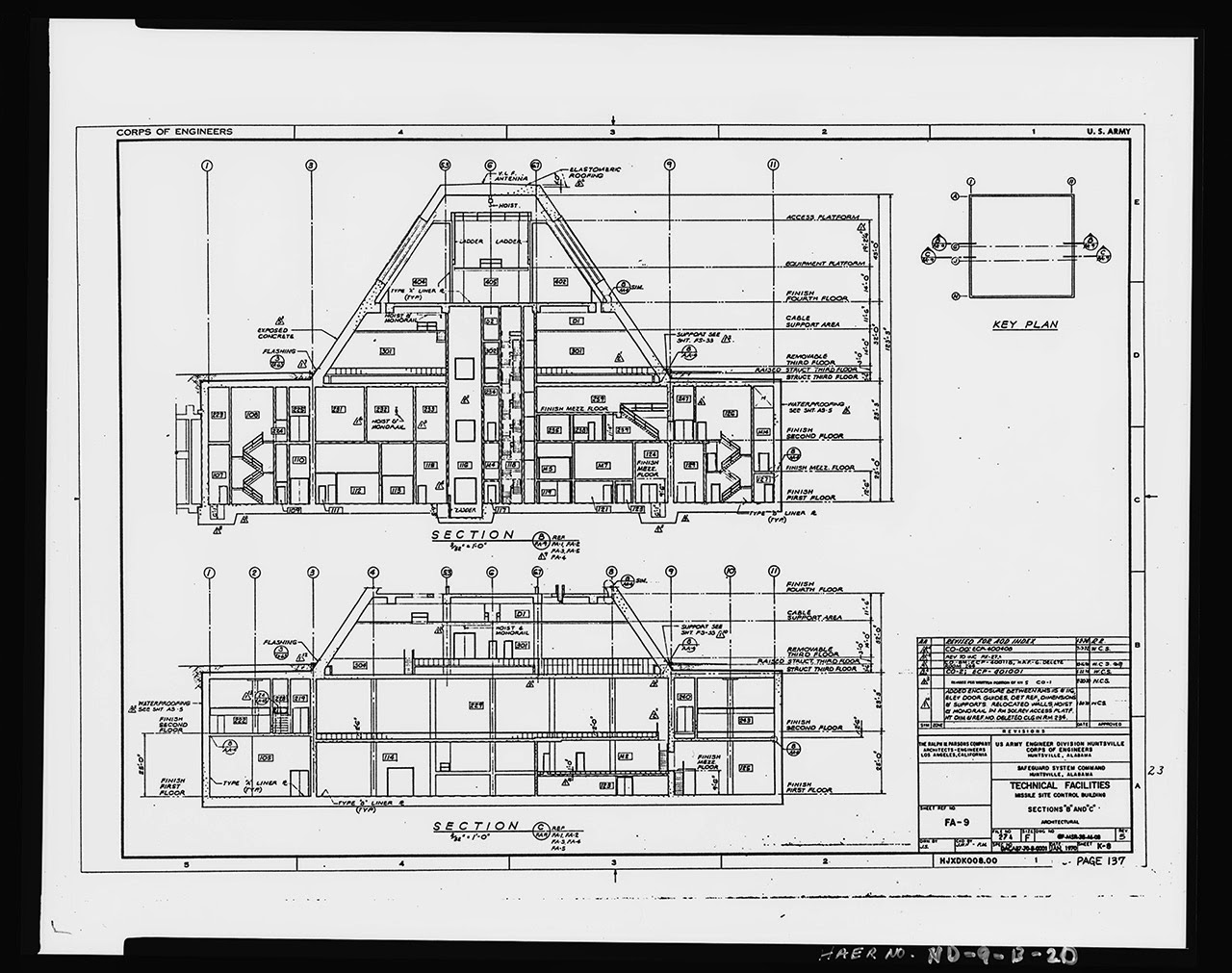

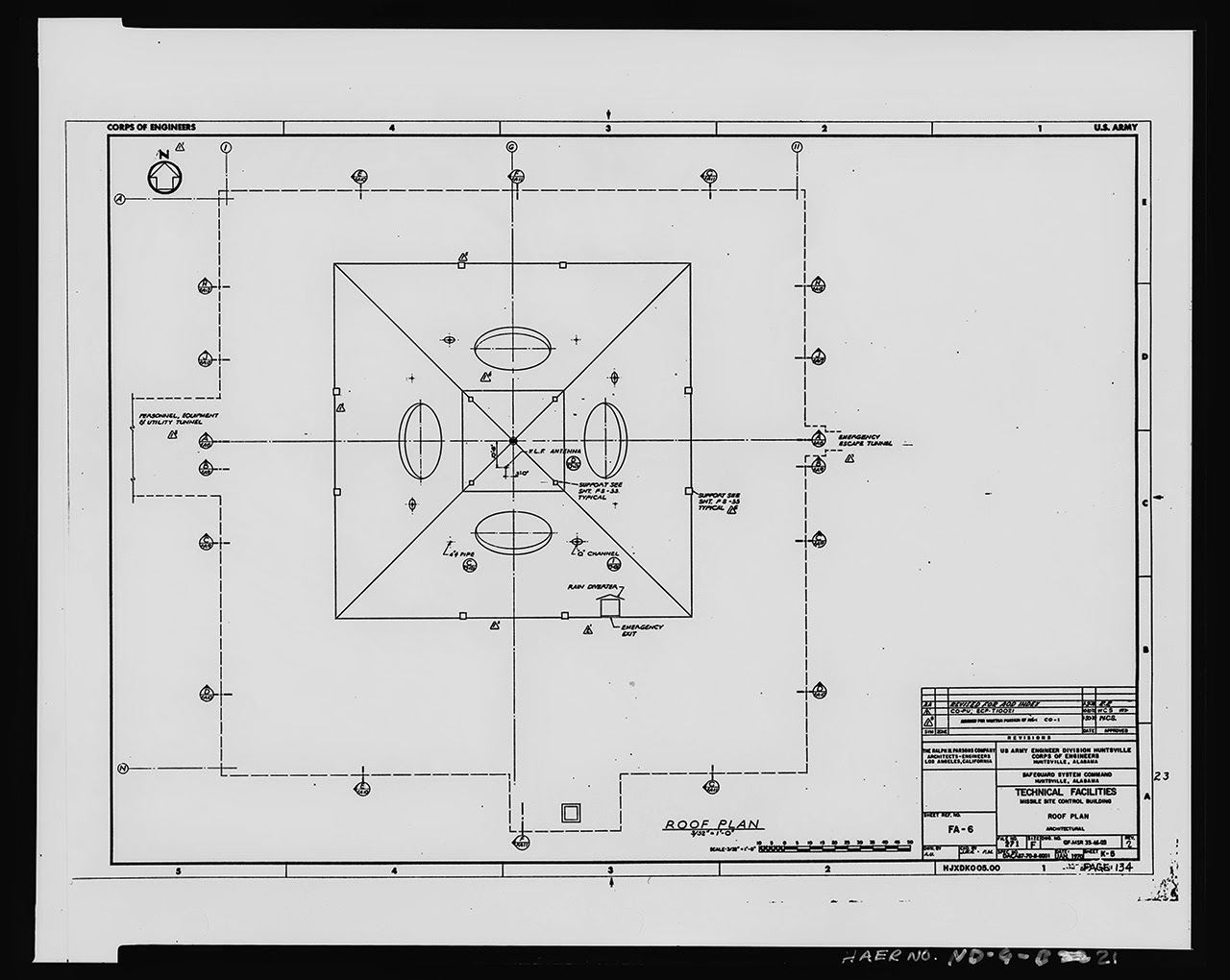

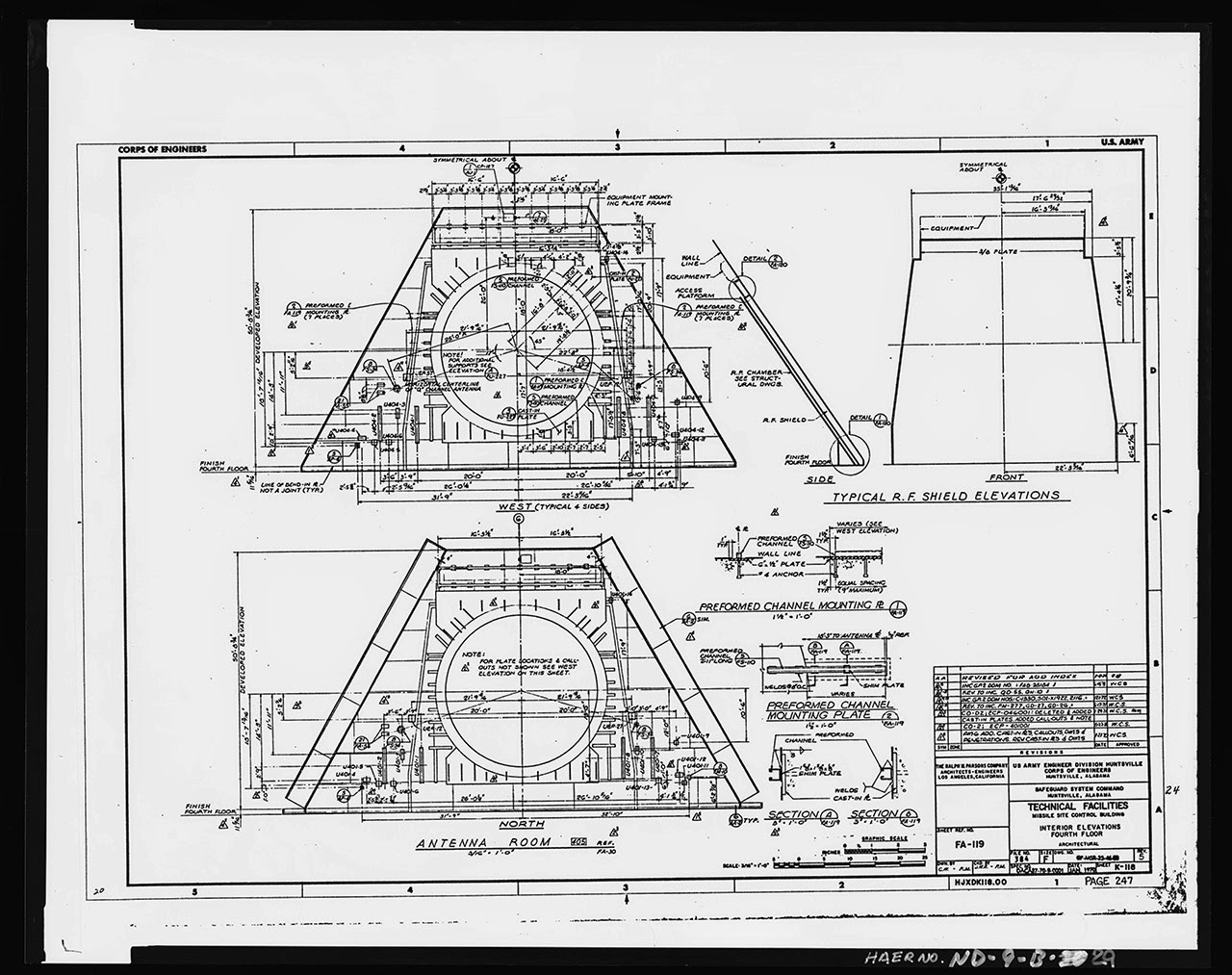

[Image: From

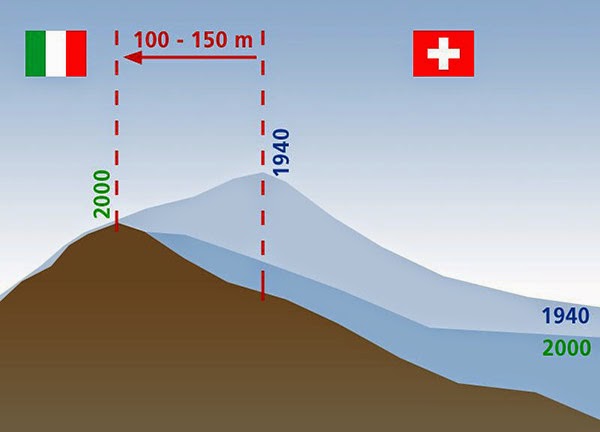

[Image: From  [Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

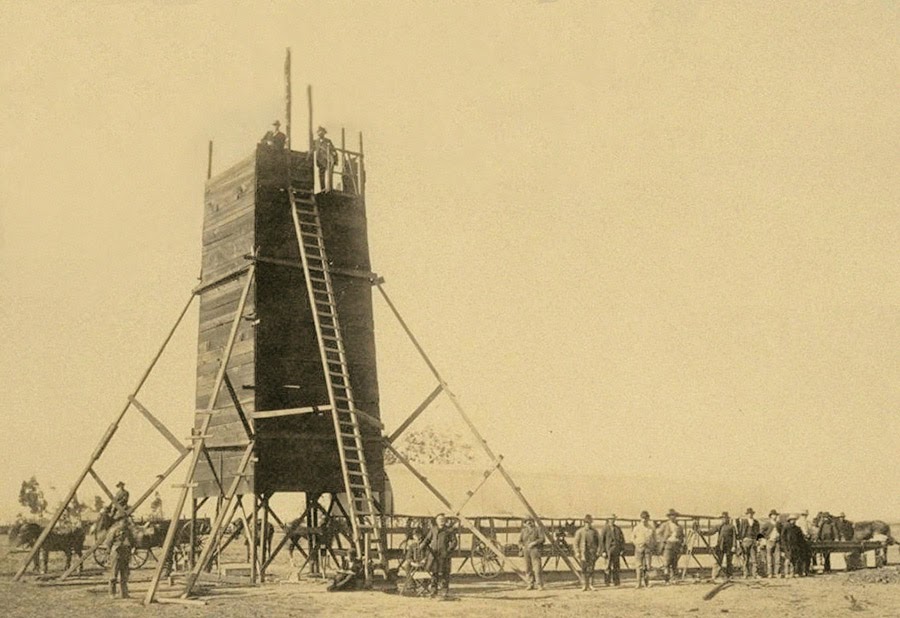

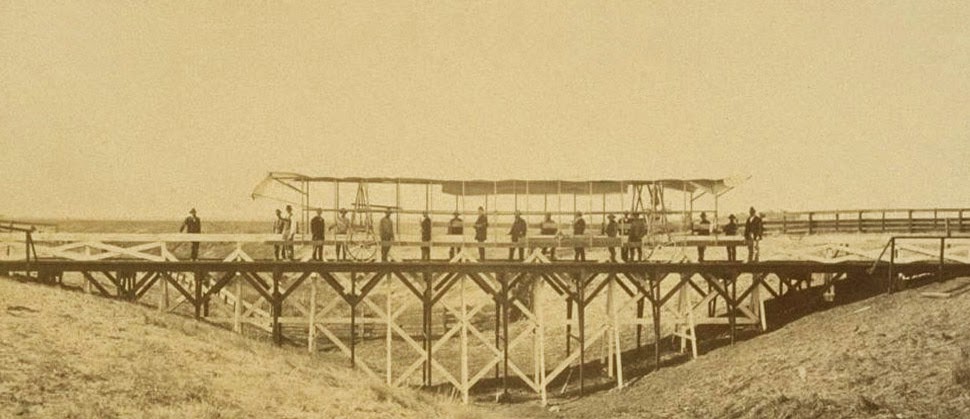

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.

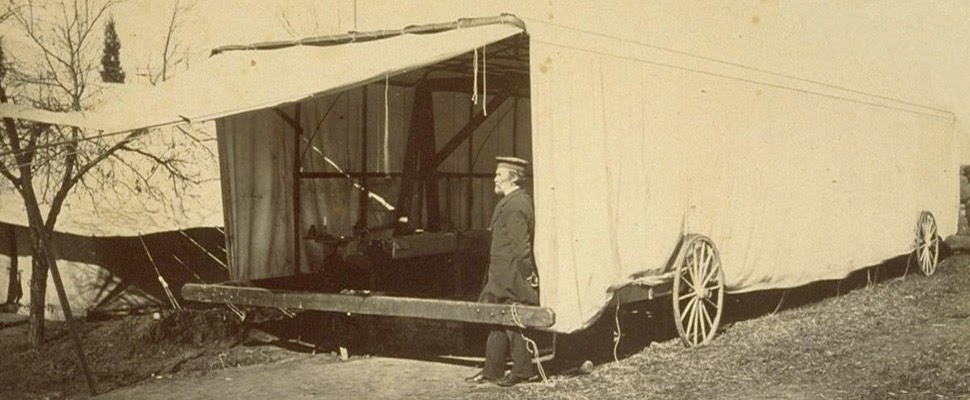

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county.  The “moveable tent or ‘

The “moveable tent or ‘ The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the

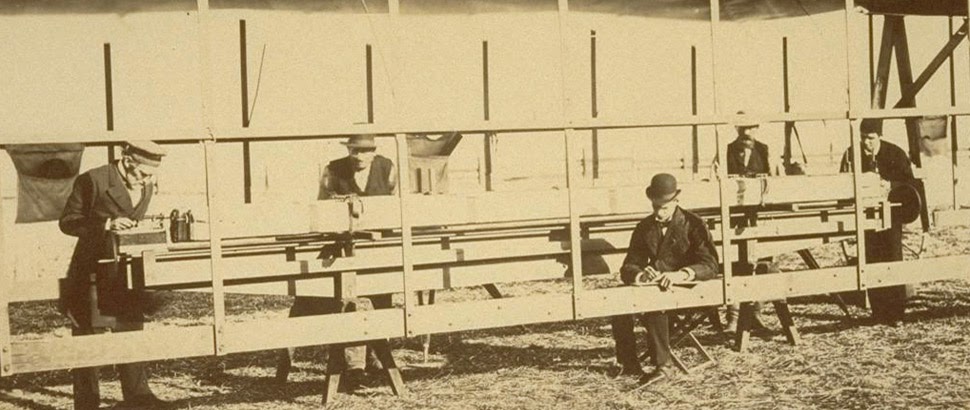

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the  In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.  That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land. Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

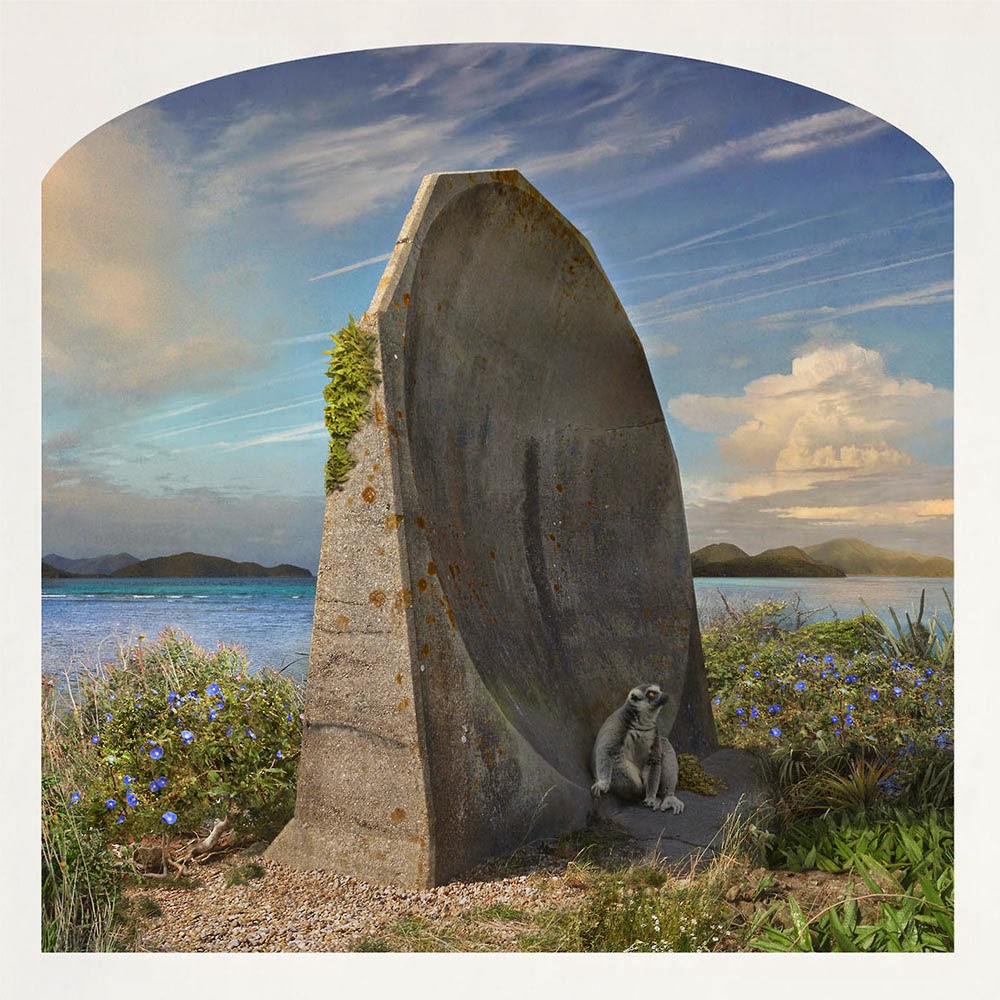

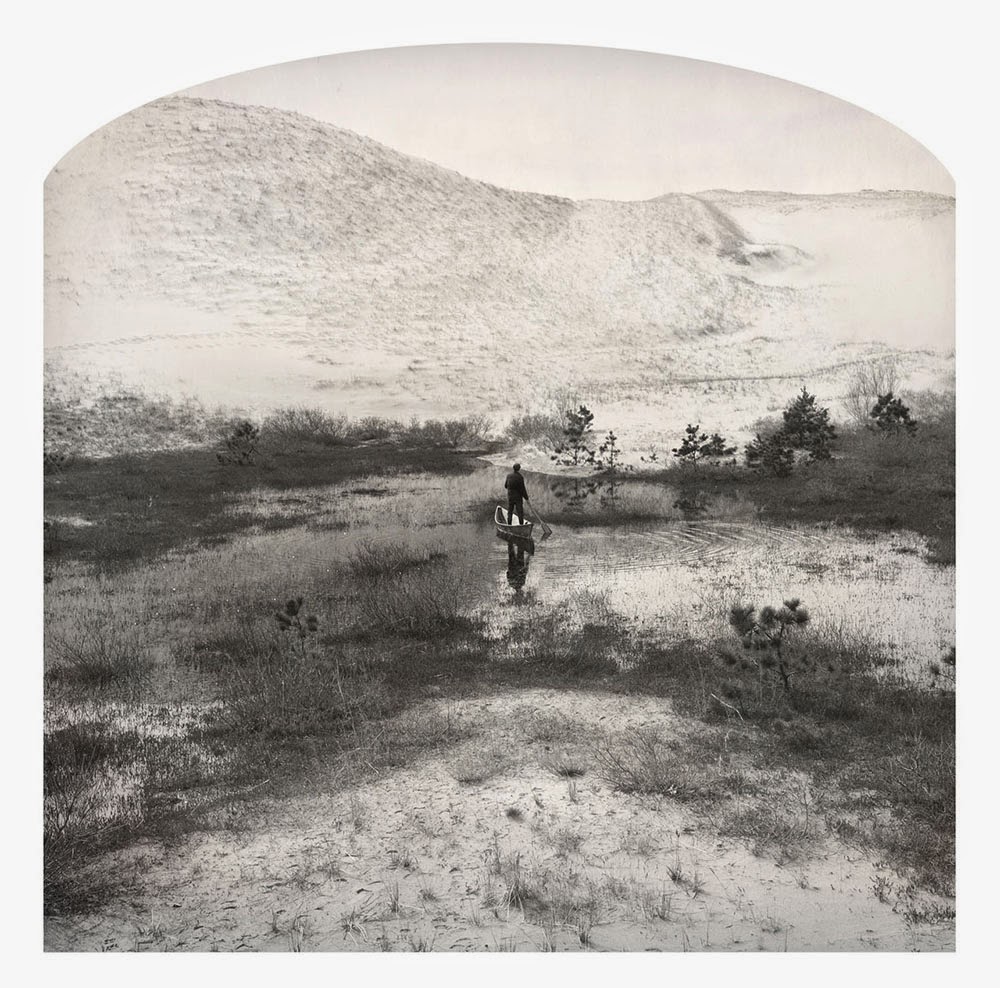

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: