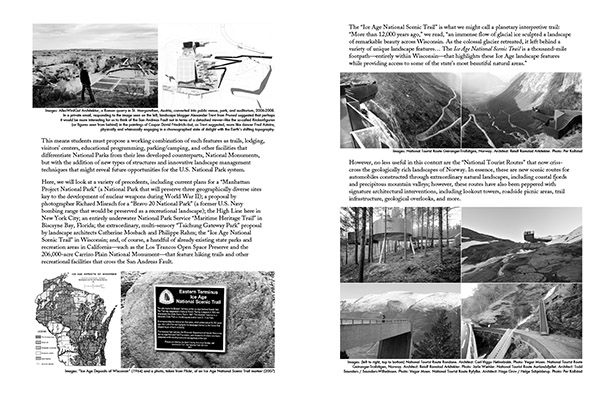

Many of today’s most original and bizarre visions of alternative worlds and landscapes come from the workshops of Hollywood effects studios. Behind the scenes of nondescript San Fernando Valley offices and warehouse spaces (if not outside California altogether, in many of the other nodes in the ever-expanding global network of cinematic effects production, from suburban London to Wellington, New Zealand), lurk the multidisciplinary teams whose job it is to create tomorrow’s monsters.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion applies make-up to actor Ron Perlman, as Hellboy.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion applies make-up to actor Ron Perlman, as Hellboy.

Spectral Motion, the effects house responsible for some of the most technically intricate and physically stunning animatronic creatures seen in feature film today, is no exception. Based in a small strip of anonymous one-story warehouse spaces squeezed in between a freeway and rail tracks, and overshadowed by a gargantuan Home Depot, Spectral Motion has developed monsters, effects, and other mechanical grotesqueries that have since become household nightmares, if not names.

Since its founding, by Mike & Mary Elizalde in 1994, the firm has worked on such films as Hellboy & Hellboy II: The Golden Army, Looper, Attack the Block, Blade 2 & Blade: Trinity, X-Men: First Class, The Watch, and this summer’s highly anticipated Pacific Rim.

This winter, while out in Los Angeles on a trip for Venue, I had the enormous pleasure of stopping by Spectral Motion with Nicola Twilley in order to interview Mike Elizalde, CEO of Spectral Motion, on a cloudy day in Glendale to talk all things monstrous and disturbing. To a certain extent, this interview thus forms the second part in a series with BLDGBLOG’s earlier interview with Hellboy creator Mike Mignola, and the present conversation, reproduced below, pairs well with Mignola’s thoughts on what we might call landscapes of monstrosity.

Our conversation with Elizalde ranged from the fine line that separates the grotesque and the alien to the possibility of planetary-scale creatures made using tweaked geotextiles, via the price of yak hair and John Carpenter’s now-legendary Antarctic thriller, The Thing.

Mike Elizalde behind his desk at Spectral Motion.

Mike Elizalde behind his desk at Spectral Motion.

Elizalde, a good-humored conversationalist, not only patiently answered our many questions—with a head cold, no less—but then took us on a tour through Spectral Motion‘s surprisingly large workshop. We saw miniature zombie heads emerging from latex molds (destined for a film project by Elizalde’s own son), costumes being sewn by a technician named Claire Flewin for an upcoming attraction at Disneyland, and a bewildering variety of body parts—heads, torsos, claws, and even a very hairy rubber chest once worn by footballer Vinnie Jones in X-Men: The Last Stand—that were either awaiting, or had already performed, their celluloid magic.

The visit ended with a screening of Spectral Motion‘s greatest hits, so to speak, with in-house photographer and archivist Kevin McTurk—a chance to see the company’s creations in their natural habitat. We walked back out into the flat light and beige parking lots of the Valley, a landscape enlivened by our heightened sense of the combination of close observation and inspired distortion required to transform the everyday into the grotesque.

Geoff Manaugh: I’d love to start with the most basic question of all: how would you describe Spectral Motion and what the company does?

Mike Elizalde: We are principally a prosthetics, animatronics, and special effects creature studio, but we are also a multifaceted design studio. We do a lot of different kinds of work. Most recently, for example, in partnership with one of my long-time colleagues, Mark Setrakian, we built anthropomorphic bipedal hydraulic robots that engage in battle, for a reality show for Syfy. It’s called RCL—Robot Combat League. It’s pretty astounding what these machines can do, including what they can do to each other.

Battling it out in Robot Combat League with two robots—”eight-feet tall, state-of-the-art humanoid robots controlled by human ‘robo-jockeys,'” in the words of Syfy—designed by Mark Setrakian of Spectral Motion.

Battling it out in Robot Combat League with two robots—”eight-feet tall, state-of-the-art humanoid robots controlled by human ‘robo-jockeys,'” in the words of Syfy—designed by Mark Setrakian of Spectral Motion.

Nicola Twilley: Are the robot battles choreographed, or do you genuinely not know which robot will win?

Elizalde: Oh, no, absolutely—it’s a contest. It really is about which robot will emerge as the victorious contender.

RCL is not only one of our most recent projects, but it also shows that, here at the studio, we can do everything from a very delicate prosthetic application on an actor, to an animatronic character in a film, to something that’s completely out of our comfort zone—like building battling robots.

I always tell people that, if they come in here with a drawing of a car, we could build that car. It is a very diverse group that we work with: artists, technicians, and, of course, we use all the available or cutting-edge technologies out there in the world to realize whatever it is that we are required to make.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion shows us a creature.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion shows us a creature.

Manaugh: What kind of design briefs come to you? Also, when a client comes to you, typically how detailed or amorphous is their request?

Elizalde: Sometimes it is very vague. But, typically, what happens is we’re approached with a script for a project. Our job is to go through the script and create a breakdown and, ultimately, a budget based on those breakdowns. We take whatever we think we should build for that script and we make suggestions as to how each thing should look—what should move, what the design should be, and so on.

Other times, we’ll be working with a director who’s very involved and who maybe even has some technical knowledge of what we do—especially someone like Guillermo del Toro. He’s completely savvy about what we do because he used to own a creature shop of his own, so working with someone like him is much more collaborative; he comes to us with a much more clear idea of what he wants to see in his films. Lots of times, he’ll even show us an illustration he’s done. He’s the first one to say, “I’m not an artist!” But he really is. He’s quite gifted.

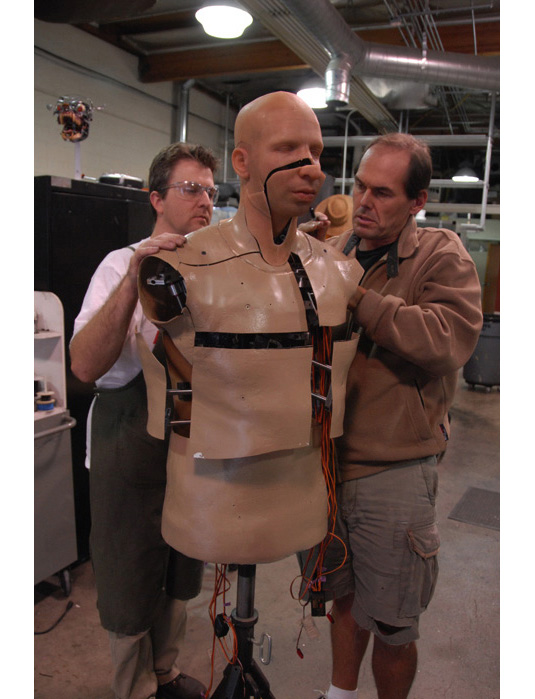

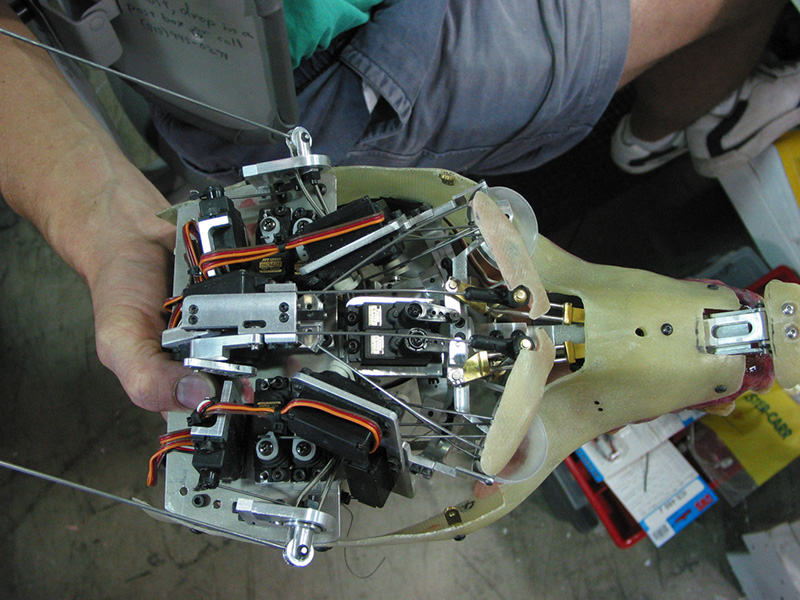

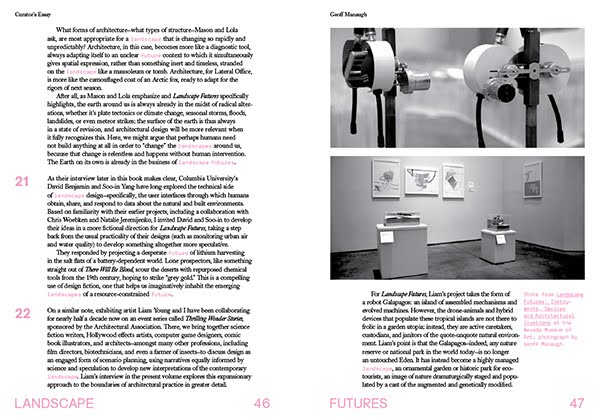

The creature known as Wink from Hellboy II: The Golden Army, designed by Spectral Motion, including a shot of the mechanical understructure used inside Wink’s left hand.

The creature known as Wink from Hellboy II: The Golden Army, designed by Spectral Motion, including a shot of the mechanical understructure used inside Wink’s left hand.

So he’ll bring us his illustrations and say, you know, “You tell me if it’s going to be a puppet, an animatronic puppet, or a creature suit that an actor can wear.” And that’s where our knowhow comes in. That’s how it evolves.

There are also times—with the robot show, for example—where they know exactly what they need but they don’t know how to achieve it. In those cases, they come to us to do that for them.

Twilley: Can you talk us through one of the projects you’ve worked on where you had to create your vision based solely on what’s in the script, rather than more collaborative work with the director? What’s that process like?

Elizalde: Well, I’d actually say that ninety percent of our work is that way. For most of the projects we work on, we do, in fact, just get a script and the director says, “Show me what this looks like.” But we love that challenge. It’s really fun for us to get into the artistic side of developing what the appearance of something will end up looking like.

We had a lot of fun working with a director named Tommy Wirkola, for example, who directed Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters. He was the director of Dead Snow, a really strange Norwegian film that involved this group of young kids who go off to a cabin where they’re hunted down by a hoard of horrifying zombie Nazi monsters. It’s really grisly.

Anyway, although Tommy did have really good ideas about what he wanted his characters to look like for Hansel & Gretel, there were certain characters whose descriptions were much more vague—also because there was such a broad scope of characters in the film. So they did rely on us to come up with a lot of different looks based on loose descriptions. In the end, the principal characters in the film were total collaborations between Tommy, myself, and Kevin Messick, the producer, and the rest of my team here at Spectral Motion, of course.

I’d say that’s a good example of both worlds, where you have some clear ideas about a few characters, but, for another group of characters, there really isn’t a whole lot of information or a detailed description. You have to fill in a lot of blanks.

Mark Setrakian, Thom Floutz , and Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion pose with Sammael from Hellboy.

Mark Setrakian, Thom Floutz , and Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion pose with Sammael from Hellboy.

Twilley: What kinds of things do you look for in a script to give you a clue about how a character might work—or is that something that simply comes out when you’re sketching or modeling?

Elizalde: In a script, we basically know what we’re looking for: “Enter a monster.” We know that’s what we’re going be doing, so we look for those moments in the script. Sometimes there’s a brief description—something like, “the monster’s leathery hide covered in tentacles.” That kind of stuff gives us an immediate visual as to what we want to create. Then we explore it with both two-dimensional artwork and three-dimensional artwork, and both digital and physical.

In fact [gestures at desk], these are some examples of two-dimensional artwork that we’ve created to show what a character will look like. This [points to statuette above desk] is a maquette for one of the characters in Hellboy II—the Angel of Death. This was realized at this scale so that del Toro could see it and say, “That’s it. That’s what I want. Build that.” This actually began as an illustration that Guillermo did in his sketchbook, a very meticulous and beautiful illustration that he came to us with.

The Angel of Death from Hellboy II: The Golden Army.

The Angel of Death from Hellboy II: The Golden Army.

But that’s the process: illustration and then maquette. Sometimes, though, we’ll do a 3D illustration in the computer before we go to the next stage, just to be able to look at something virtually, in three dimensions, and to examine it a little bit more before we invest the energy into creating a full-blown maquette.

The maquette, as a tool, can be very essential for us, because it allows us to work out any bugs that might be happening on a larger scale, design-wise. Practically speaking, it doesn’t give us a lot of information as to how the wings are going to work, or how it’s going to function; but it does tell us that a human being could actually be inside of it and that it could actually work as a full-scale creature. It’s essential for those reasons.

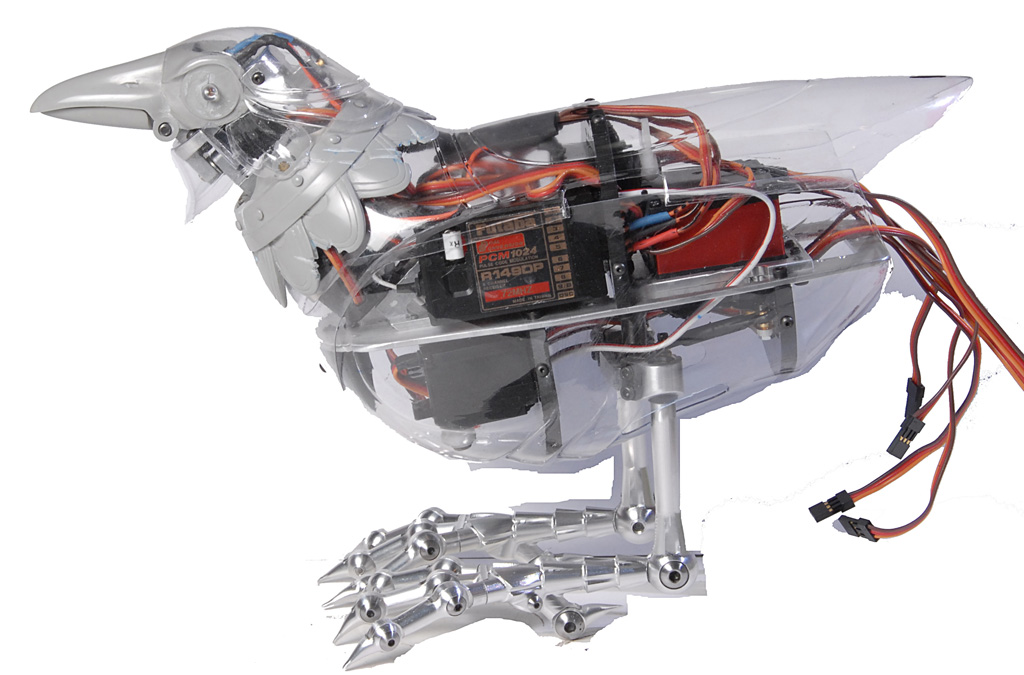

Simon, the mechanical bird from Your Highness, before paint has been applied, revealing the internal workings.

Simon, the mechanical bird from Your Highness, before paint has been applied, revealing the internal workings.

Because you can show a director a drawing, and it might look really terrific—but, when it comes to actually making it, in a practical application at scale, sometimes the drawing just doesn’t translate. Sometimes you need the maquette to help describe what the finished piece will look like.

Manaugh: You mentioned animatronics and puppeteering. We were just up at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena yesterday afternoon, talking to them about how they program certain amounts of autonomy into their instruments, especially if it’s something that they’re putting on Mars. It has to be able to act on its own, at times, because it doesn’t have enough time to wait for the command signal from us back on Earth. I’m curious, especially with something like the robot combat show, how much autonomy you can build into a piece. Can you create something that you just switch on and let go, so that it functions as a kind of autonomous or even artificially intelligent film prop?

Elizalde: It really depends on the application. For example, when we’re filming something, a lot of times there’s a spontaneity that’s required. Sometimes actors like to ad lib a little bit. If we need to react to something that an actor is saying via a puppet—an animatronic puppet—then that live performance really is required. But we always have the option of going to a programmable setup, one where we can have a specific set of parameters, performance-wise, to create a specific scene.

For live performances on a stage, we’d probably want to program that with the ability to switch over to manual, if required. But, if it’s scripted—if it’s a beat-by-beat performance—then we know that can be programmable. We can turn on the switch and let it go. In the middle of that, you can then stop it, and have a live show, with puppeteers in the background filling in the blanks of whatever that performance is, and then you can continue with the recorded or programmed performance.

It really goes back and forth, depending on what it is the people who are putting on the production need.

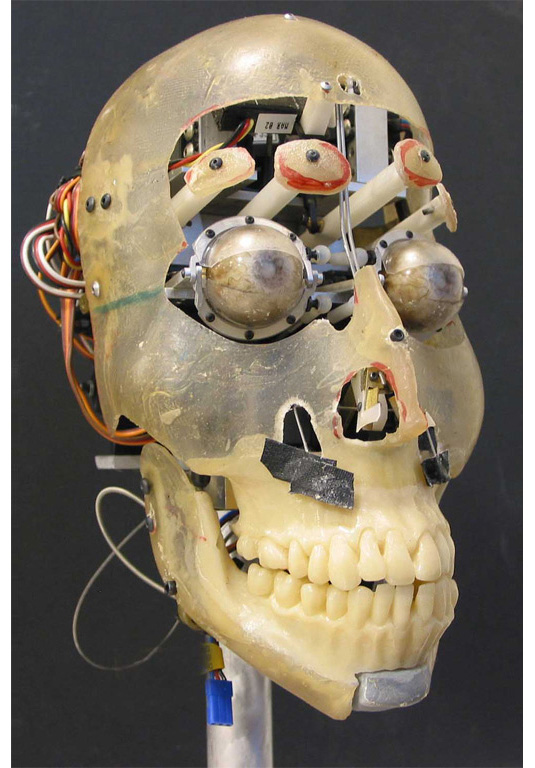

The mechanical skull under structure of the Ivan the Corpse from Hellboy.

The mechanical skull under structure of the Ivan the Corpse from Hellboy.

Twilley: That’s an interesting point—the idea of how a live actor responds to your creatures. Have there been any surprises in how an actor has responded, or do they all tend to know what they’re getting into by the time you’re filming?

Elizalde: They do know what they’re getting into, but it’s always rewarding to have an actor go over to the thing that you built, and stare at it, and say, “Oh, my God! Look at that thing!” They can feed off of that. I think they are able to create a more layered performance, with a lot more depth in their reactions to something if it’s actually there—if it’s present, if it has life to it, and it’s tactile.

A lot of times people turn to digital solutions. That’s also good, if the application is correct. But, you know, a lot of directors that we talk to are of the mind that a practical effect is far better for exactly that reason—because the actor does have a co-actor to work with, to play off of, and to have feelings about.

That’s one of the things that keeps us going. And, the fact is, with this business, no matter what walks through that door we know that it’s going to be a completely different set of challenges from the last thing that we did.

Mechanical puppet of Drake from a Sprite commercial. Scott Millenbaugh and Jurgen Heimann of Spectral Motion are seen here making mechanical adjustments.

Mechanical puppet of Drake from a Sprite commercial. Scott Millenbaugh and Jurgen Heimann of Spectral Motion are seen here making mechanical adjustments.

Manaugh: About six years ago, I interviewed a guy who did concept art for the Star Wars prequels, and he had a kind of pet obsession with building upside-down skyscrapers—that is, skyscrapers that grew downwards like stalactites. He kept trying to get them into a movie. He would build all of these amazing 3D models and show them to the director, and the director was always excited—but then he’d turn the model upside-down and say, “Let’s do it like this!” So all the upside-down skyscrapers would just be right-side up again. In any case, this artist was then working on the recent Star Trek reboot, and there’s a brief moment where you see upside-down skyscrapers on the planet Vulcan. It’s only on screen for about a second and a half, but he finally did it—he got his upside-down skyscrapers into a film.

Elizalde: [laughs] But, ohhh! For half-a-second! [laughter]

Manaugh: Exactly. Anyway, in the context of what you do here at Spectral Motion, I’m curious if there is something like that, that you’ve been trying to get into a movie for the last few years but that just never quite makes it. A specific monster, or a new material, or even a particular way of moving, that keeps getting rejected.

Elizalde: That’s an interesting question. [pauses] You know, I’d have to say no. I’d say it seems like the more freely we think, the better the result is. So it’s quite the contrary: most of the stuff we suggest actually does make it into the film, because it’s something that someone else didn’t think about. Or perhaps we’ve added some movement to a character, or we’ve brought something that will elicit a more visceral reaction from the audience—bubbly skin, for instance, or cilia that wiggle around.

I don’t think I’ve really encountered a situation where I thought something would look great, but, when I brought it to a director, they said, “Nah—I don’t think that’s going to go. Let’s not try that.” They always seem to say, “Let’s try it! It sounds cool!”

Mike Elizalde applies some last-minute touch-ups to actor Ron Perlman on the set of Hellboy.

Mike Elizalde applies some last-minute touch-ups to actor Ron Perlman on the set of Hellboy.

We really haven’t had a whole lot of frustration—maybe only when it turns into a very large committee making a decision on the film. Then, I suppose, a certain degree of frustration is more typical. But that happens in every industry, not just ours: the more people are involved in deciding something, the more difficult it is to get a clear image of what it is we’re supposed to do.

Manaugh: When we first spoke to set-up this interview, I mentioned that we’d be touring the landfill over at Puente Hills this morning, on our way here to meet you—it’s the biggest active landfill in the United States. What’s interesting is that it’s not only absolutely massive, it’s also semi-robotic, in the sense that the entire facility—the entire landscape—is a kind of mechanical device made from methane vents and sensors and geotextiles, and it grows everyday by what they call a “cell.” A “cell” is one square-acre, compacted twenty feet deep with trash. Everyday!

But I mention this because, during our visit there, I almost had the feeling of standing on top of a mountain-sized creature designed by Spectral Motion—a strange, half-living, half-mechanical monstrosity in the heart of the city, growing new “cells” every day of its existence. It’s like something out of Hellboy II. So I’m curious about the possibilities of a kind of landscape-scale creature—how big these things can get before you need to rely on CGI. Is it possible to go up to that scale, or what are the technical or budgetary limitations?

A Tyrannosaurus rex in a bathtub in the back prep rooms of Spectral Motion.

A Tyrannosaurus rex in a bathtub in the back prep rooms of Spectral Motion.

Elizalde: We can’t build mountains yet but, absolutely, we can go way up in scale! Many times, of course, we have to rely, at least to some degree, on digital effects—but that just makes our job easier, by extending what is possible, practically, and completing it cinematically, on screen, at a much larger scale.

For example, on Pacific Rim, Guillermo del Toro’s new film that comes out this summer, we designed what are called Jaegers. They’re basically just giant robots. And we also designed the Kaiju, the monsters in the film. First, we created maquettes, just like the ones here, and we made several versions of each to reflect the final designs you’ll see in the film. Those were taken and re-created digitally so they could be realized at a much larger scale.

To that degree, we can create something enormous. There’s a maquette around here somewhere of a character we designed for the first Hellboy movie—actually, there are two of them. One of those characters is massive—about the size of a ten-story building—and the other one is much, much bigger. It’s the size of… I don’t know, a small asteroid. There really is no limit to the scale, provided we can rely on a visual effects company to help us realize our ultimate goal.

The animatronic jaws and bioluminescent teeth (top) of the alien creature (bottom) designed by Spectral Motion for Attack the Block.

The animatronic jaws and bioluminescent teeth (top) of the alien creature (bottom) designed by Spectral Motion for Attack the Block.

But going the opposite direction, scale-wise, is also something that interests us. We can make something incredibly tiny, depending on what the film requires. There is no limit in one direction or the other as to what can be achieved, especially with the power of extension through digital effects.

Manaugh: Just to continue, briefly, with the Puente Hills reference, something that we’ve been interested in for the past few years is the design of geotextiles, where companies like TenCate in the Netherlands are producing what are, effectively, landscape-scale blankets made from high-quality mesh, used to stabilize levees or to add support to the sides of landfills. But some of these geotextiles are even now getting electromagnetic sensors embedded in them, and there’s even the possibility of a geotextile someday being given mechanical motion—so it’s just fascinating, I think, to imagine what you guys could do with a kind of monstrous or demonic geotextile, as if the surface of the earth could rise up as a monster in Hellboy III.

Elizalde: [laughs] Well, now that I know about it, I’ll start looking into it!

Twilley: Aside from scale, we’re also curious about the nature of monsters in general. This is a pretty huge question, but what is a monster? What makes something monstrous or grotesque? There seems to be such a fine line between something that is alien—and thus frightening—and something that is so alienating it’s basically unrecognizable, and thus not threatening at all.

Elizalde: Exactly. Right, right.

Twilley: So how do you find that sweet spot—and, also, how has that sweet spot changed over time, at least since you’ve been in the business? Are new things becoming monstrous?

Elizalde: Well, I think my definition of a monster is simply a distortion: something that maybe looks close to a human being, for example, but there’s something wrong. It can be something slight, something subtle—like an eye that’s just slightly out of place—that makes a monster. Even a little, disturbing thing like that can frighten you.

So it doesn’t take a lot to push things to the limit of what I would consider the grotesque or the monstrous. At that point, it runs the gamut from the most bizarre and unimaginable things that you might read in an H. P. Lovecraft story to something simple, like a tarantula with a human head. Now there’s something to make me scream! I think there’s a very broad range. But you’re right: it’s a huge question.

Mark Setrakian of Spectral Motion working on the animatronic head of Edward the Troll from Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters.

Mark Setrakian of Spectral Motion working on the animatronic head of Edward the Troll from Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters.

And sometimes the monstrous defies definition. I guess it’s more of a primal reaction—something you can’t quite put your finger on or describe, but something that makes you feel uneasy. It makes you feel uncomfortable or frightened. A distortion of what is natural, or what you perceive as natural, something outside what you think is the order of things—or outside what you think is acceptable within what we’ve come to recognize as natural things—then that’s a monster. That’s a monstrous thing.

Do you recall seeing John Carpenter’s The Thing?

Manaugh: It’s one of my favorite movies.

Elizalde: My goodness, the stuff in that film is the stuff of nightmares. It really is brilliantly executed, and it’s a great inspiration to all of the people in our industry who love monsters, and to all the fans all over the world who love monstrous things.

Actor Ron Perlman gets make-up applied for his role as Hellboy, as director Guillermo del Toro and Mike Elizalde from Spectral Motion stop in for a visit.

Actor Ron Perlman gets make-up applied for his role as Hellboy, as director Guillermo del Toro and Mike Elizalde from Spectral Motion stop in for a visit.

Twilley: Have there been trends over time? In other words, do you find directors look for a particular kind of monster at a particular moment in time?

Elizalde: I do think there are trends—although I think it’s mainly that there’s a tendency here in Hollywood where somebody hears a rumor that someone down the street is building a film around this particular creature, so that guy’s now got to write a similar script to compete. But sometimes the trends are set by something groundbreaking, like The Thing. Once that movie was released, everybody paid attention and a whole new area of exploration became available to create amazing moments in cinema.

Those are the real trends, you know. It’s a symbiosis that happens between the artistic community and the technological community, and it’s how it keeps advancing. It’s how it keeps growing. And it keeps us excited about what we do. We feed off of each other.

Technician Claire Flewin uses her hand to demonstrate how yak hair looks stretched over a mold.

Technician Claire Flewin uses her hand to demonstrate how yak hair looks stretched over a mold.

Manaugh: Speaking of that symbiosis, every once in a while, you’ll see articles in a magazine like New Scientist or you’ll read a press release coming out of a school like Harvard, saying that they’ve developed, for instance, little soft robots or other transformable, remote-control creatures for post-disaster reconnaissance—things like that. I mention this because I could imagine that you might have multiple reactions to something like that: one reaction might be excitement—excitement to discover a new material or a new technique that you could bring into a film someday—but the other reaction might be something almost more like, “Huh. We did that ten years ago.” I’m curious as to whether you feel, because of the nature of the movies that you work on, that the technical innovations you come up with don’t get the attention or professional recognition that they deserve.

Elizalde: I think your assessment is accurate on both counts. There are times when we see an innovation, or a scientific development, that we think could be beneficial to our industry; in fact, that happens all the time. There’s cross-pollination like that going on constantly, where we borrow from other industries. We borrow from the medical industry. We borrow from the aerospace industry. We borrow, really, from whatever scientific developments there are out there. We seek them out and we do employ some of those methods in our own routines and systems.

In fact, one of our main designers, and a very dear friend of mine whom I’ve worked side by side with for years now, is Mark Setrakian. When he’s not working here with us, he is a designer at one of the labs you just described.

So there is a lot of crossover there.

The mechanical skull of the scrunt from Lady in the Water.

The mechanical skull of the scrunt from Lady in the Water.

Manaugh: That’s interesting—do the people who work for you tend to come from scientific or engineering backgrounds, like Mark, or are they more often from arts schools? What kinds of backgrounds do they tend to have?

Elizalde: Generally speaking, I think they’re people like myself who just have a love for monsters. That’s honestly where a lot of people in our industry come from. There are people who started their careers as dental technicians and people who started out as mold-makers in a foundry. In all of those cases, people from those sorts of technical fields gravitate toward this work because of, first of all, a love for monsters and creatures, and, secondly, a technical ability that isn’t necessarily described as an art form per se. Electronics people love to work for us. People who design algorithms love to work for us. Even people with a background in dentistry, like I say, love to work for us.

There’s really no limit to the fields that bring people to this industry—they come from everywhere. The common thread is that we all love movies and we all love creatures. We love making rubber monsters for a living.

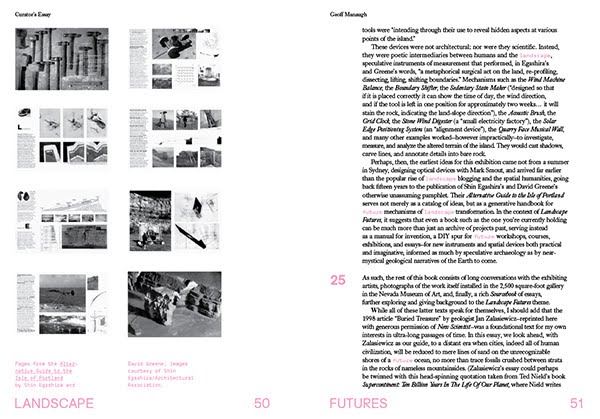

The shelves at Spectral Motion gives a good sense of the workshop’s range of reference. Highlights include the Third Edition of the Atlas of Clinical Dermatology (in color), The National Audubon Society: Speaking for Nature, Marvel’s Fantastic Four, The Graphic Works of Odilon Redon, and a Treasury of Fantastic and Mythological Creatures.

The shelves at Spectral Motion gives a good sense of the workshop’s range of reference. Highlights include the Third Edition of the Atlas of Clinical Dermatology (in color), The National Audubon Society: Speaking for Nature, Marvel’s Fantastic Four, The Graphic Works of Odilon Redon, and a Treasury of Fantastic and Mythological Creatures.

To go back to your previous question, there are definitely times when I think we don’t get a lot of exposure for what we do, but there is also, at some level, a kind of “don’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain” thing going on, where we don’t really want people to look backstage at what makes a movie work. We are creating a living creature for film, and that’s what we want to put across to the audience. In some ways, it’s actually better if there isn’t too much exposure as to how something was created; it’s like exposing a magic trick. Once you know the secret, it’s not that big a deal.

So we do live in a little bit of a shroud of secrecy—but that’s okay. After a film is released, it’s not unusual for more of what we did on that film to be exposed. Then, we do like to have our technicians, our artists, and what we’ve developed internally here to be recognized and shown to the public, just so that people can see how cool it all is.

I think, though, that my response to those kinds of news stories is really more of a happiness to see new technologies being developed elsewhere, and an eagerness to get my hands on it so I can see what we could do with it in a movie. And, of course, sometimes we develop our very own things here that maybe someone hadn’t thought of, and that could be of use in other fields, like robotics. And that’s kind of cool, too.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion sculpting an old age Nosferatu as a personal project.

Mike Elizalde of Spectral Motion sculpting an old age Nosferatu as a personal project.

Manaugh: Finally, to bring things full circle, we’re just curious as to how Spectral Motion got started.

Elizalde: Well, I became involved in the effects industry back in 1987. It sort of just dawned on me one day that I wanted to do this for a living. I had been in the Navy for eight years when it really started getting to me—when I realized I wasn’t doing what I wanted to do with my life.

I decided that I’d come back to my home, which is Los Angeles, California, and look into becoming a creature effects guy. I was totally enamored of Frankenstein’s Monster when I was a kid. I grew up watching all the horror movies that I could see—a steady diet of Godzilla, Frankenstein, you name it. All the Universal monsters, and even more modern things like An American Werewolf in London. They just really fascinated me. That was a real catalyst for me to start exploring how to do this myself.

I also learned from books. I collected books and started using my friends as guinea pigs, creating very rudimentary makeup effects on them. And, eventually, I landed my first job in Hollywood.

Cut to fifteen years later, and I had my first experience on set with Guillermo del Toro. I was working with him on Blade II. I had done an animatronic device for the characters he was using in his film, and I was also on set puppeteering. We became very good friends. That’s when he offered me the script for Hellboy and that’s how we started Spectral Motion. I became independent. Prior to that I had worked for Rick Baker, and Stan Winston, and all the other big names in town. But this was our opportunity to make our own names—and here we are, today.

You know, this is one of those industries where you can come in with a desire and some ability, and people around you will instruct you and nurture you. That’s how it happened for me. I was taught by my peers. And it really is a great way to learn. There are schools where you can learn this stuff, as well, but my experience proved to me that the self-taught/mentored method is a very good way to go.

This interview was simultaneously published on Venue, where a long list of other interviews discussing the human relationship to the virtual, built, and natural landscapes can be found.

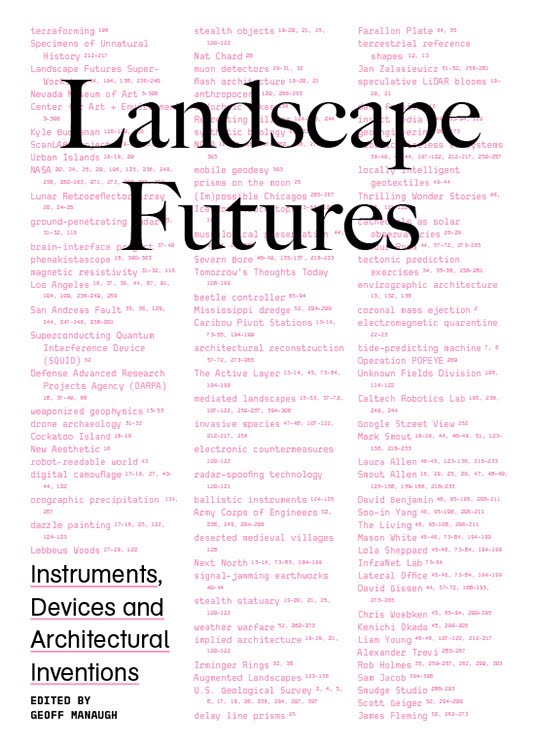

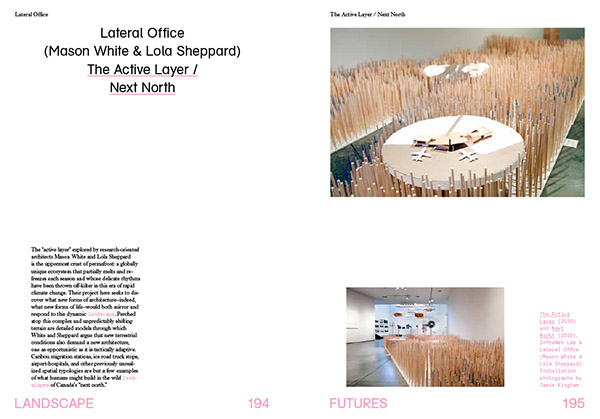

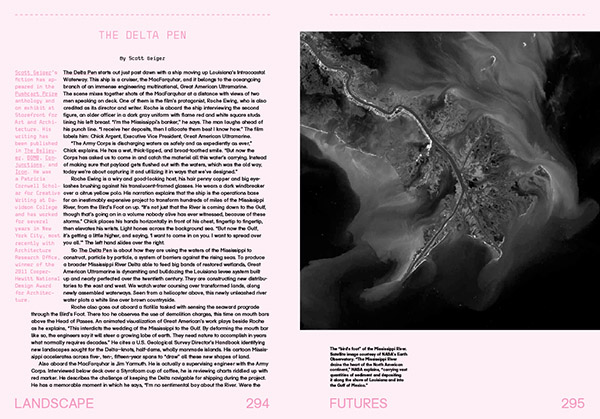

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The cover of

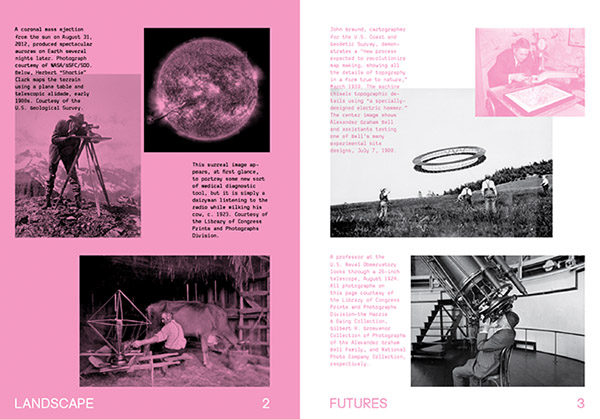

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: The opening spreads of

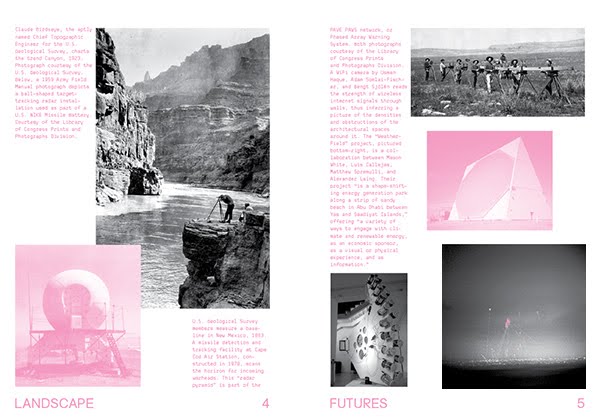

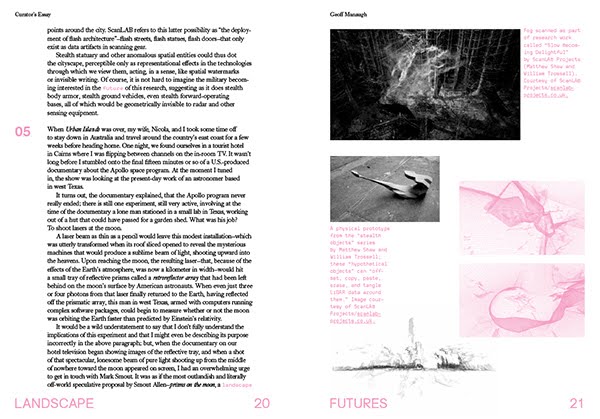

[Images: More spreads from

[Images: More spreads from

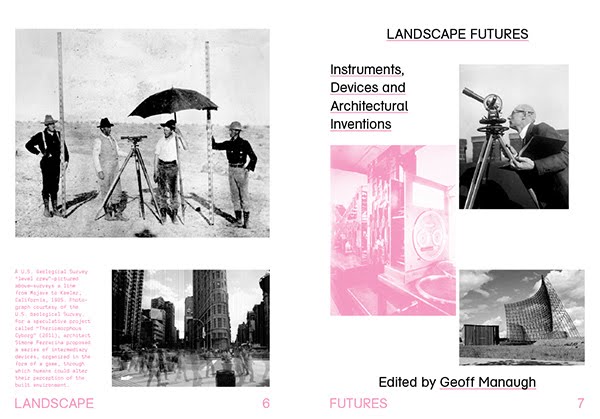

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

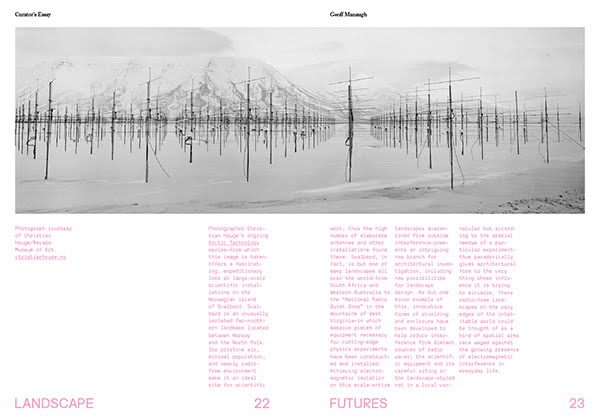

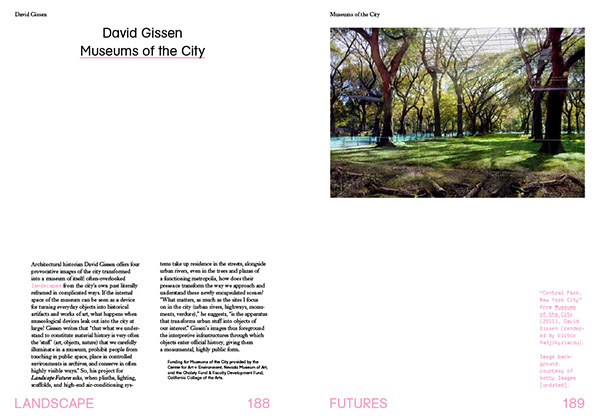

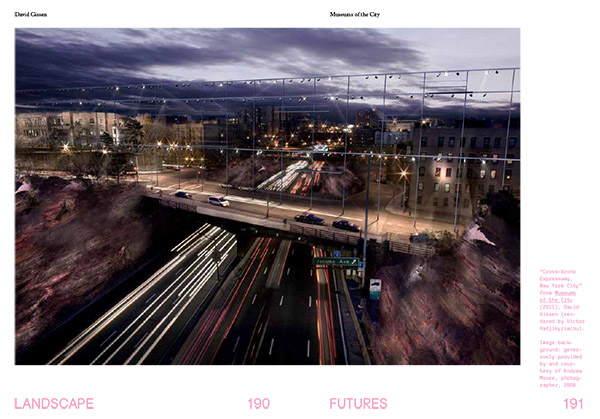

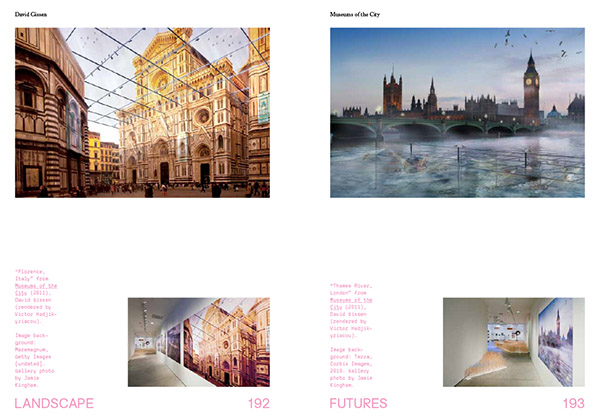

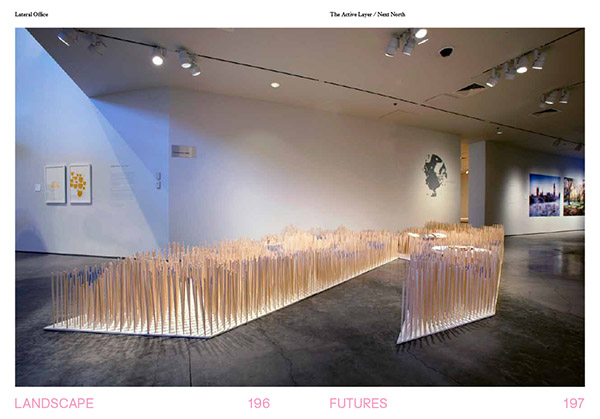

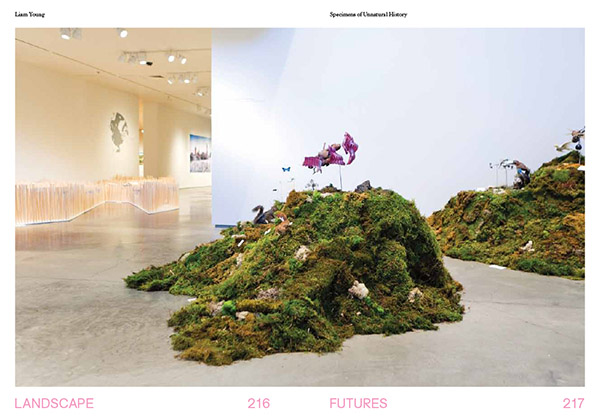

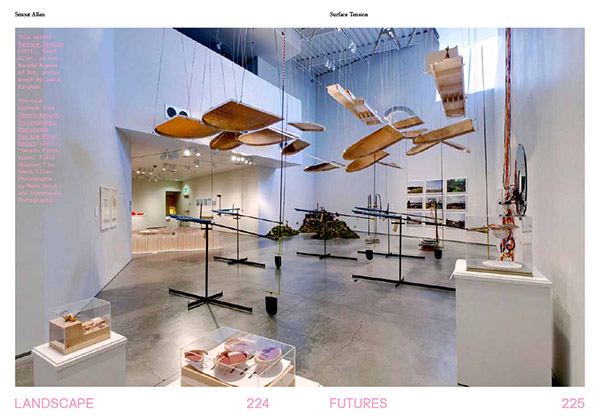

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

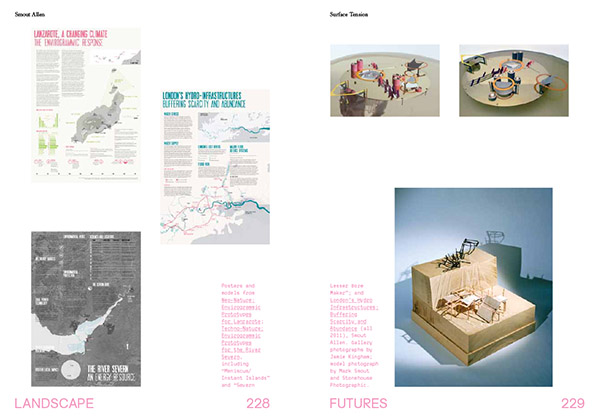

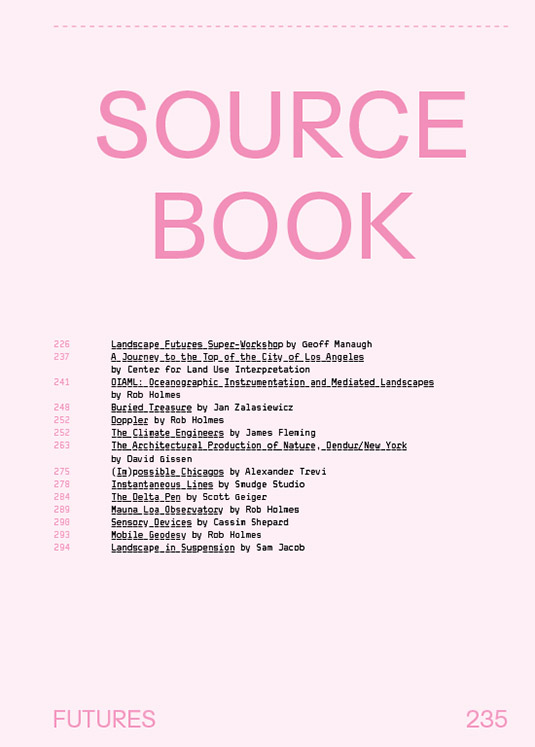

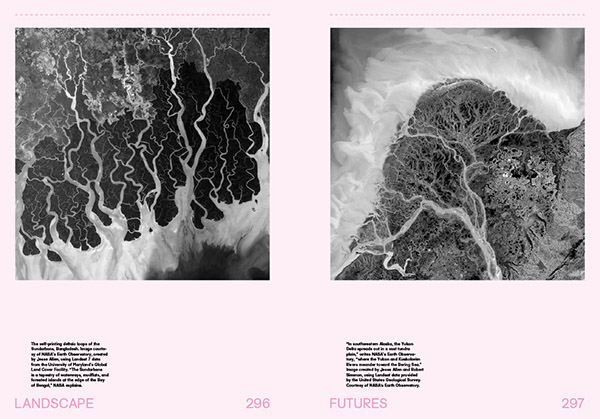

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

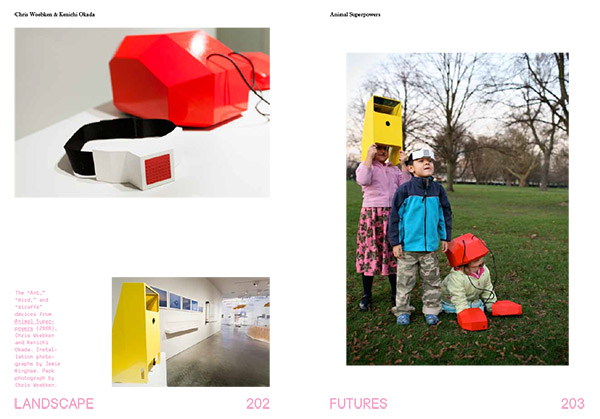

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

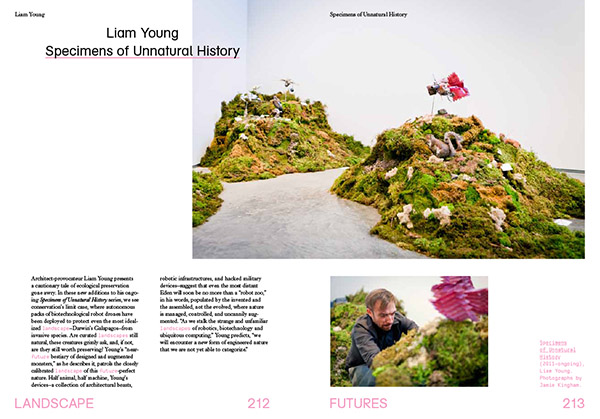

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “

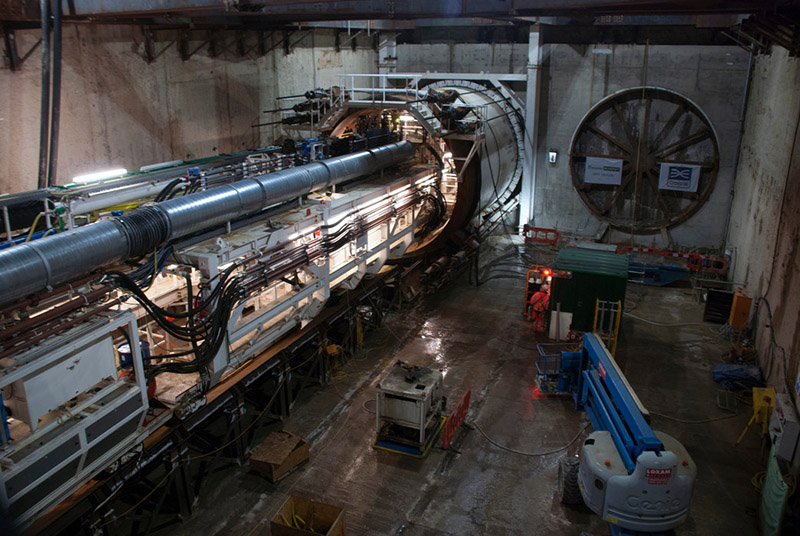

[Image: Machines slide beneath the streets, via

[Image: Machines slide beneath the streets, via

[Image: Looking down through shafts into the subcity, via

[Image: Looking down through shafts into the subcity, via  [Image: Phyllis, via

[Image: Phyllis, via

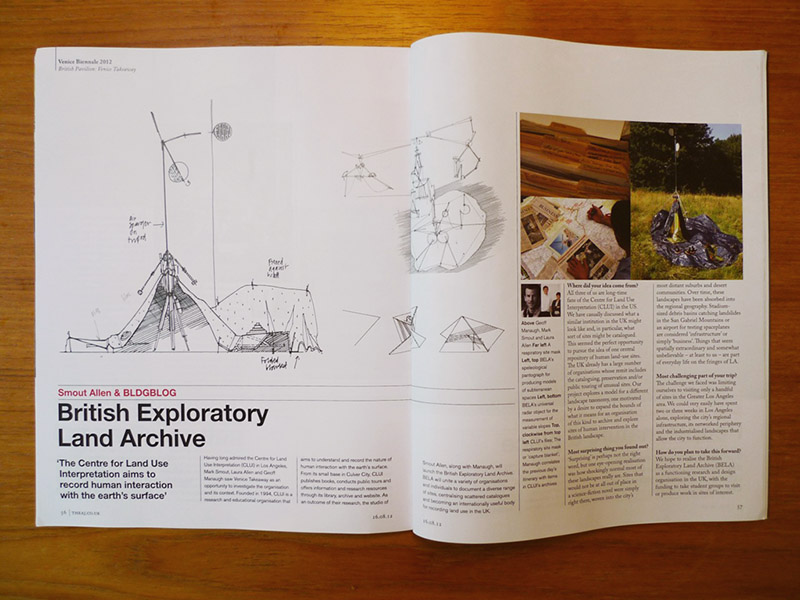

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

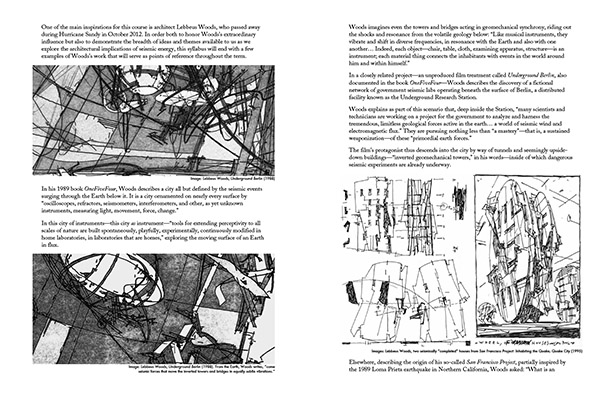

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995)]. [Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″].

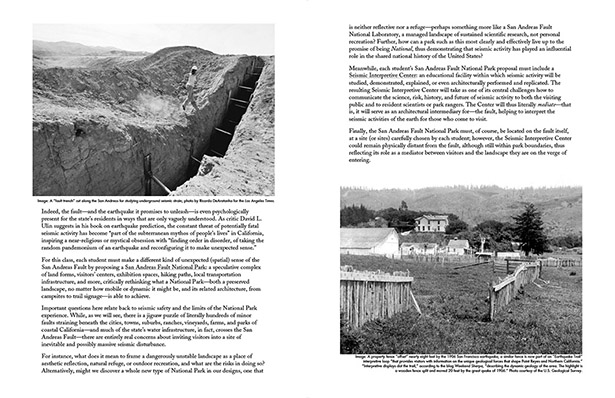

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, from San Francisco Project: Inhabiting the Quake, Quake City (1995) and an aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, looking south across the Carrizo Plain at approximately +35° 6′ 49.81″, -119° 38′ 40.98″]. [Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “

[Images: (left) A “fault trench” cut along the San Andreas for studying underground seismic strain; photo by Ricardo DeAratanha for the Los Angeles Times. (right) A property fence “offset” nearly eight feet by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; a similar fence is now part of an “ [Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?].

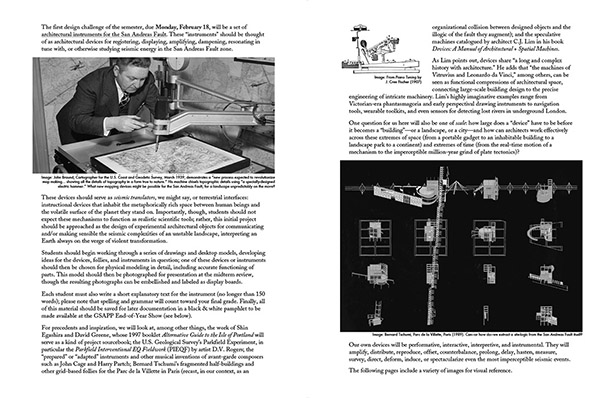

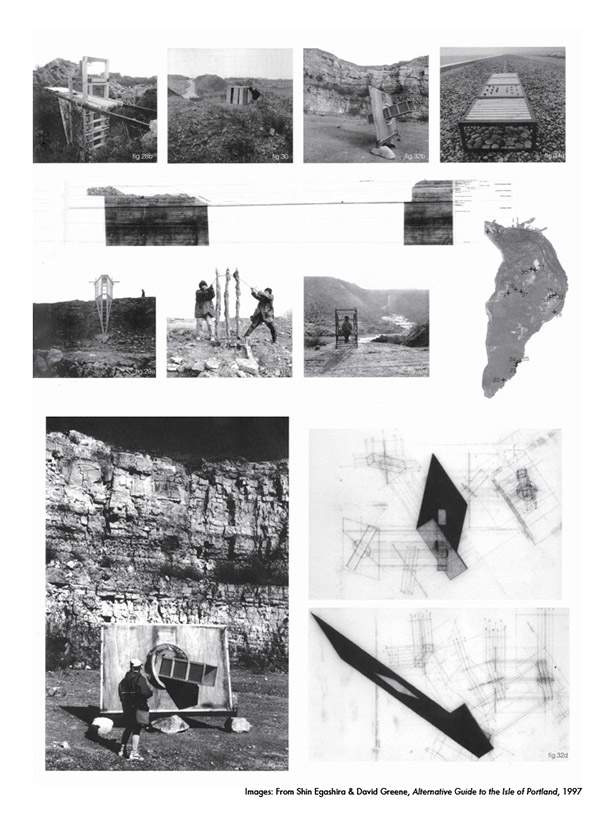

[Images: (left) John Braund, Cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, March 1939, demonstrates a “new process expected to revolutionize map making… showing all the details of topography in a form true to nature.” His machine chisels topographic details using “a specially-designed electric hammer.” What new mapping devices might be possible for the San Andreas Fault, for a landscape unpredictably on the move? (right top) From Piano Tuning by J. Cree Fischer (1907). (right bottom) Bernard Tschumi, Parc de la Villette, Paris (1989). Can—or how do—we extract a site-logic from the San Andreas Fault itself?]. [Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

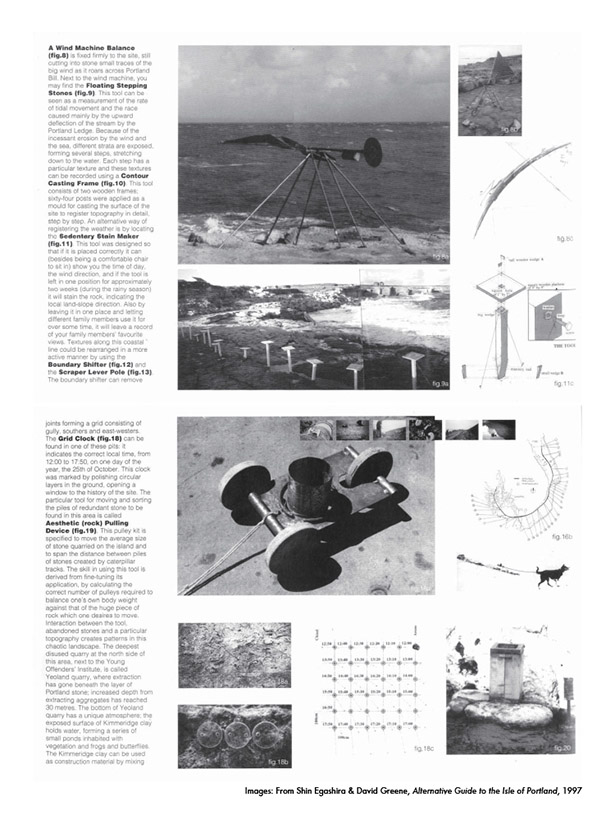

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)]. [Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)].

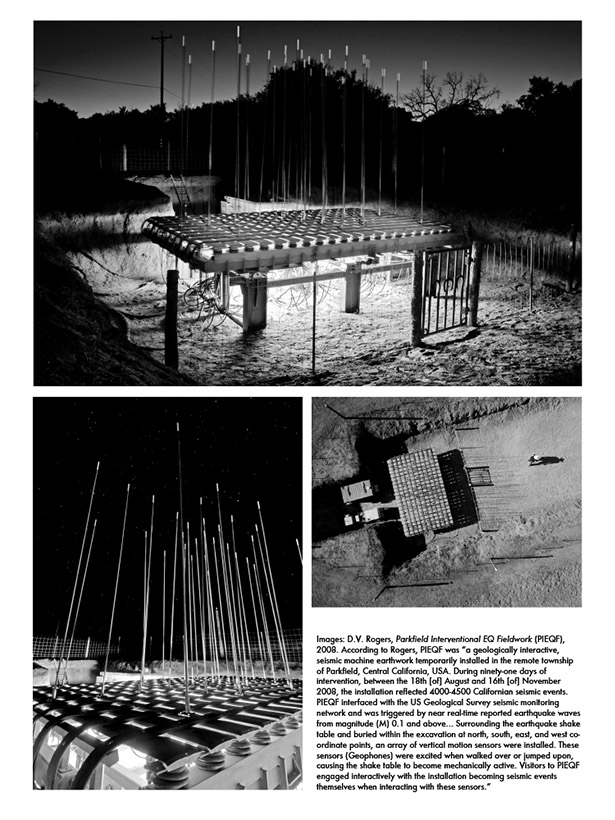

[Images: From Shin Egashira & David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (1997)]. [Images: D.V. Rogers,

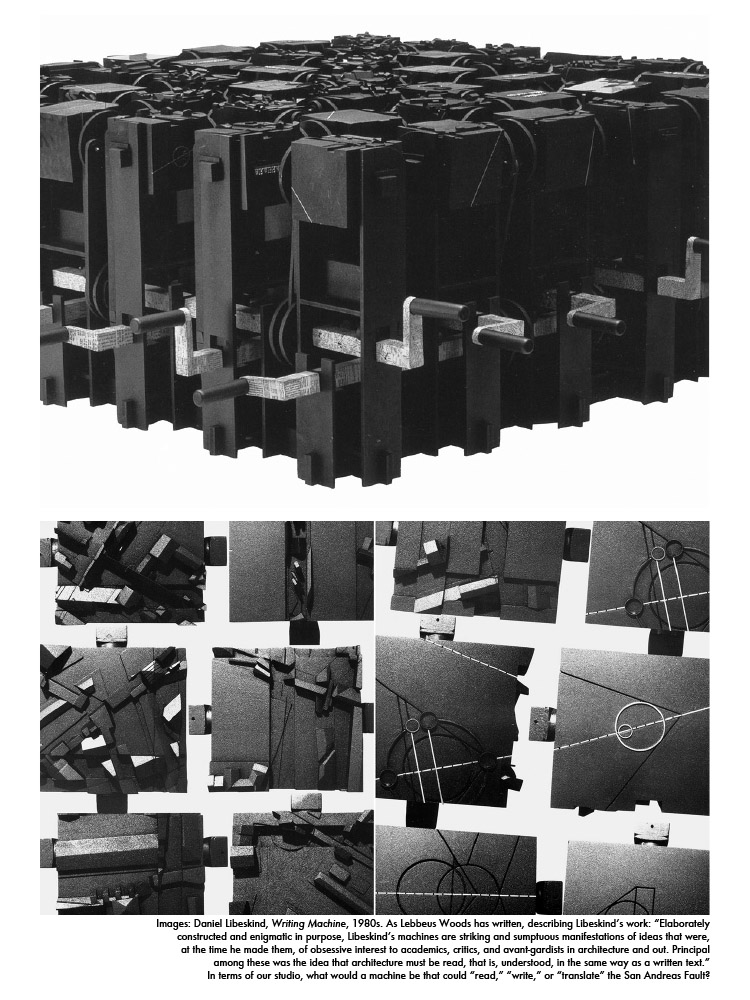

[Images: D.V. Rogers,  [Images: Daniel Libeskind,

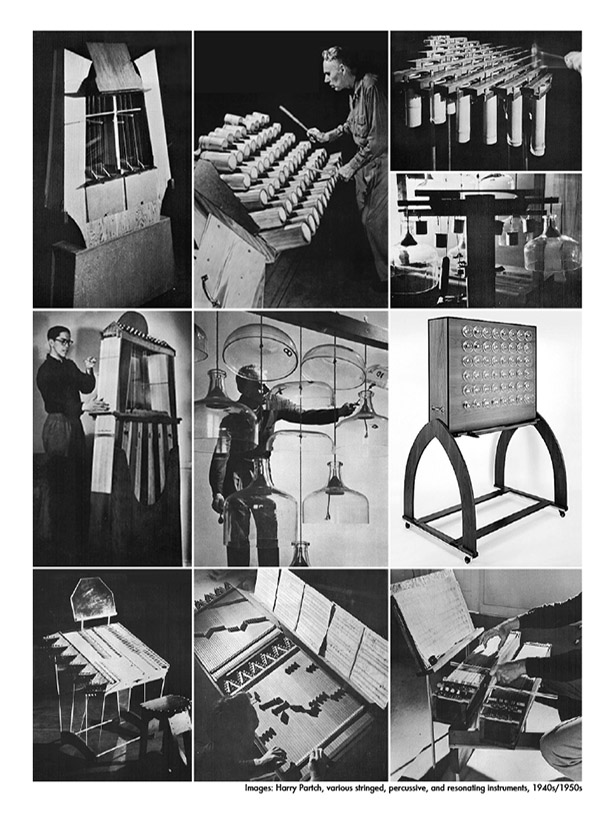

[Images: Daniel Libeskind,  [Images:

[Images:  [Images: (left)

[Images: (left)  [Images: (left top)

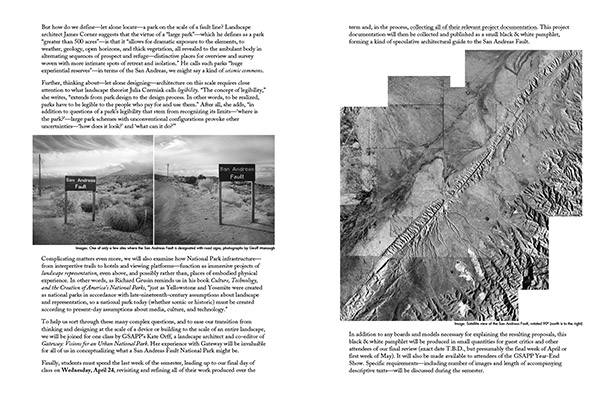

[Images: (left top)  [Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

[Images: (left) One of only a few sites where the San Andreas Fault is designated with road signs; photographs by Geoff Manaugh. (right) Satellite view of the San Andreas Fault, rotated 90º (north is to the right)]. [Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from

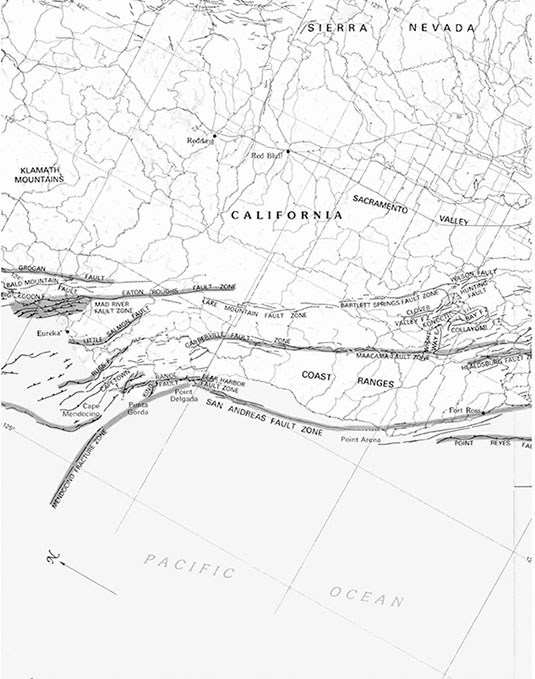

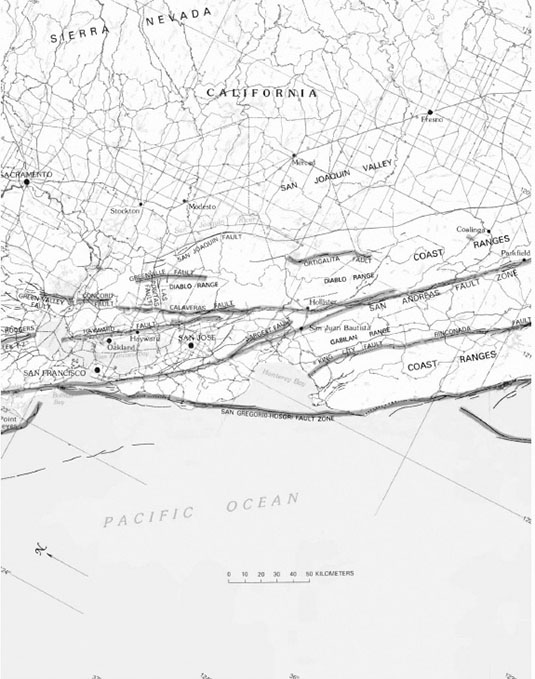

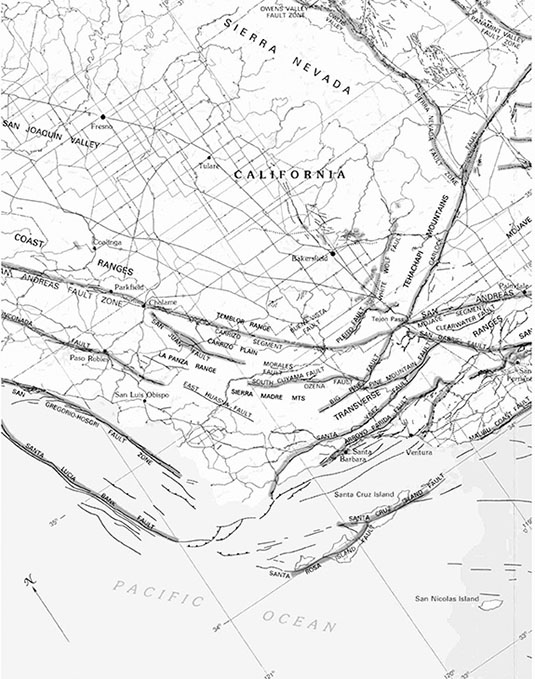

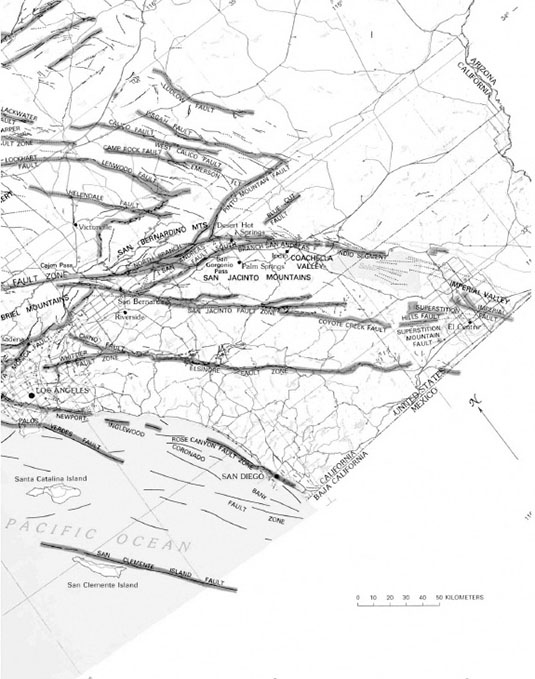

[Images: (left top and bottom) Lebbeus Woods, from  [Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in

[Image: A map in four sections (see below three images) shows the San Andreas Fault stretching from northern to southern California. The San Andreas “is just one of several faults that make up a complex of potential catastrophes,” paleontologist Richard Fortey writes in  [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 (

[Image: Map courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, from The San Andreas Fault System, U.S.G.S. Professional Paper 1515 ( [Image: (left) A

[Image: (left) A

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via  [Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

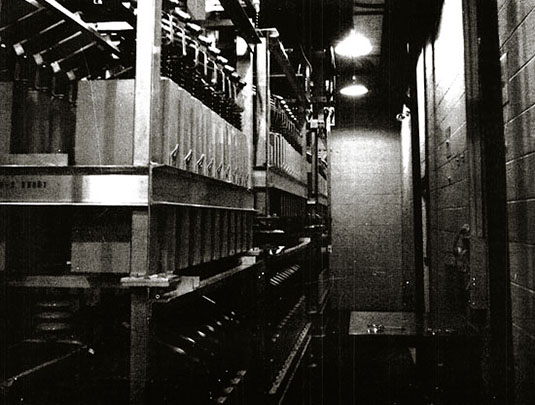

[Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)]. [Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna].

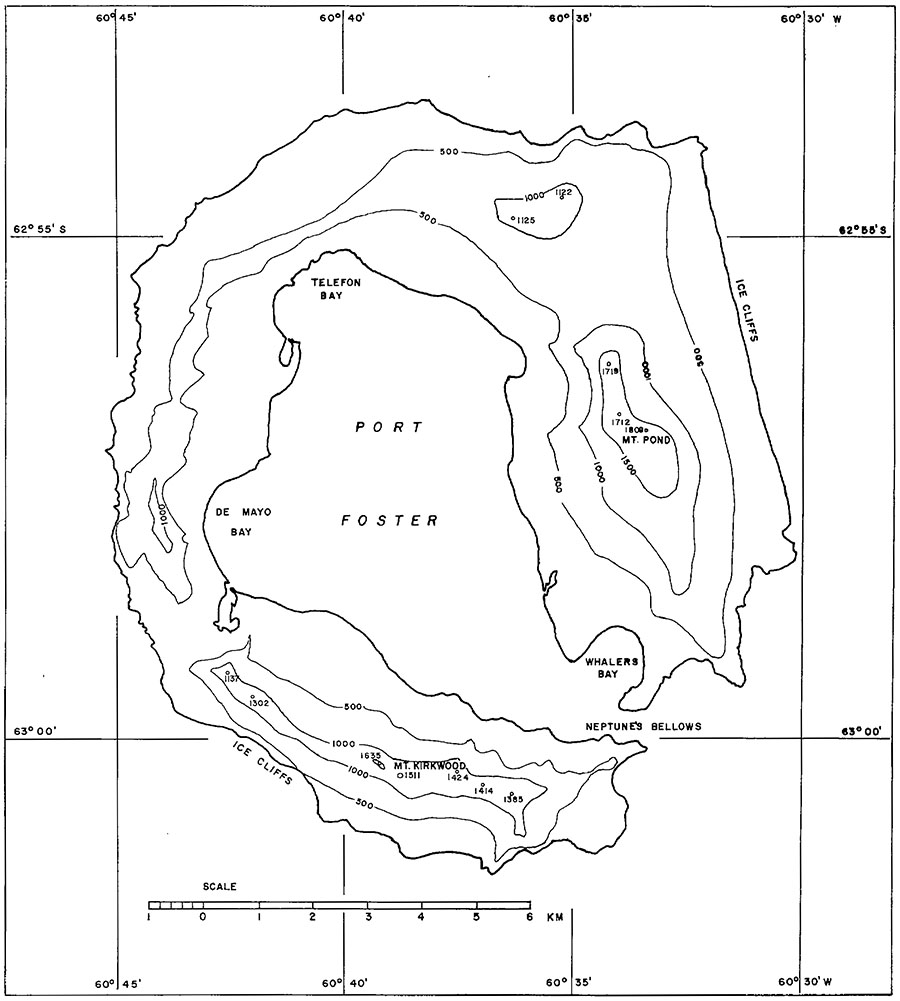

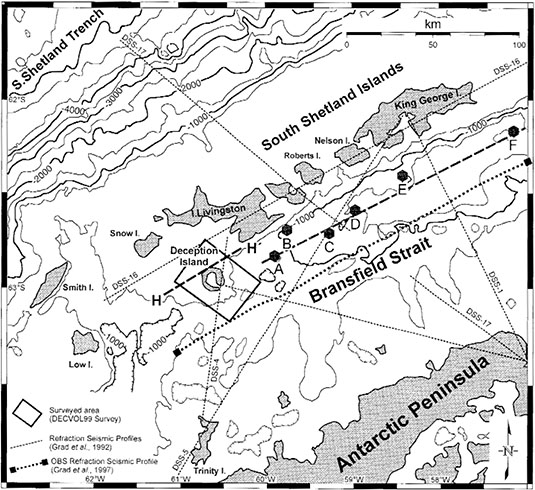

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna]. [Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)].

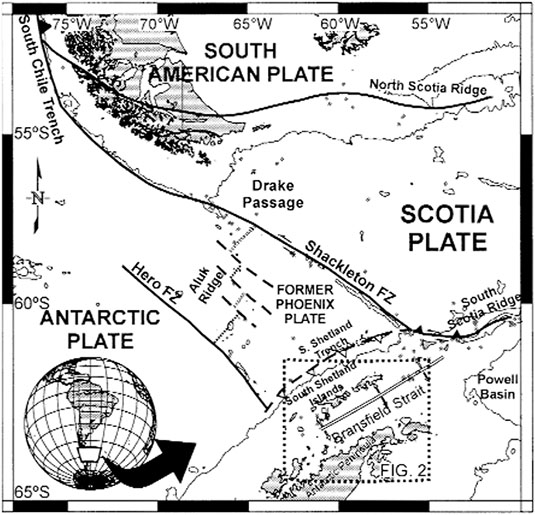

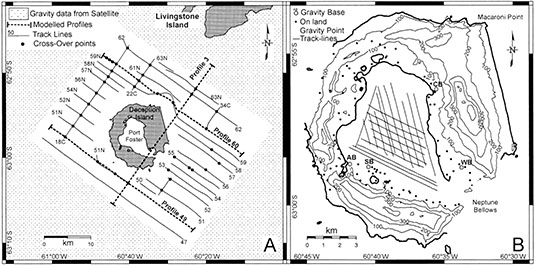

[Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

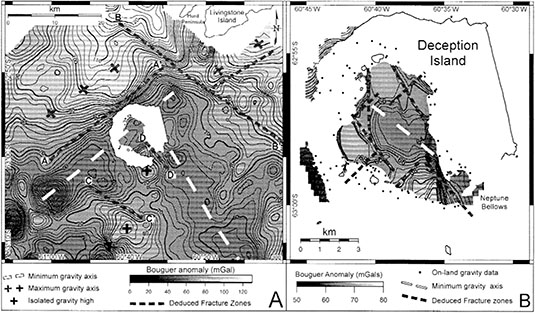

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

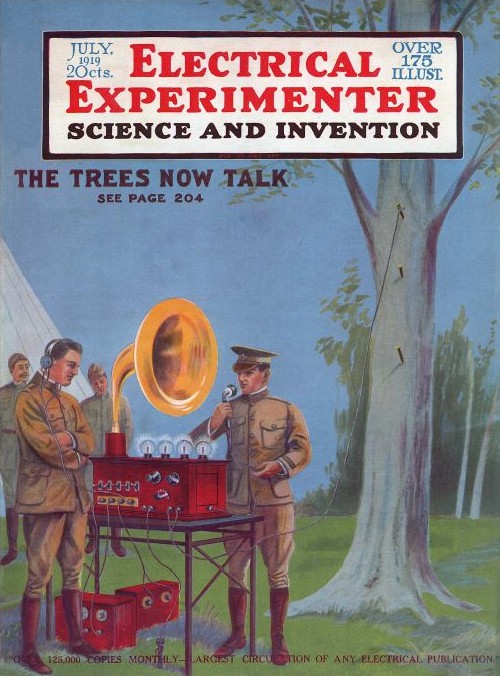

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

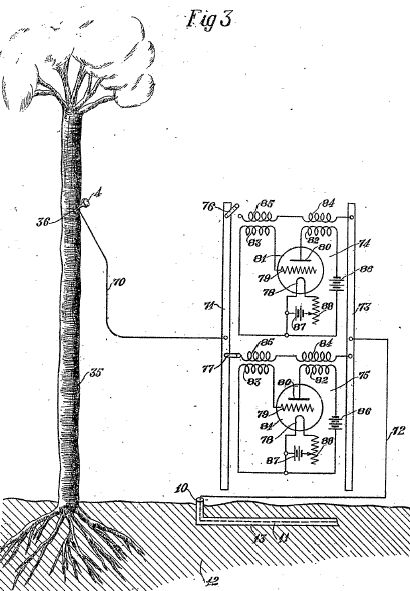

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via  [Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

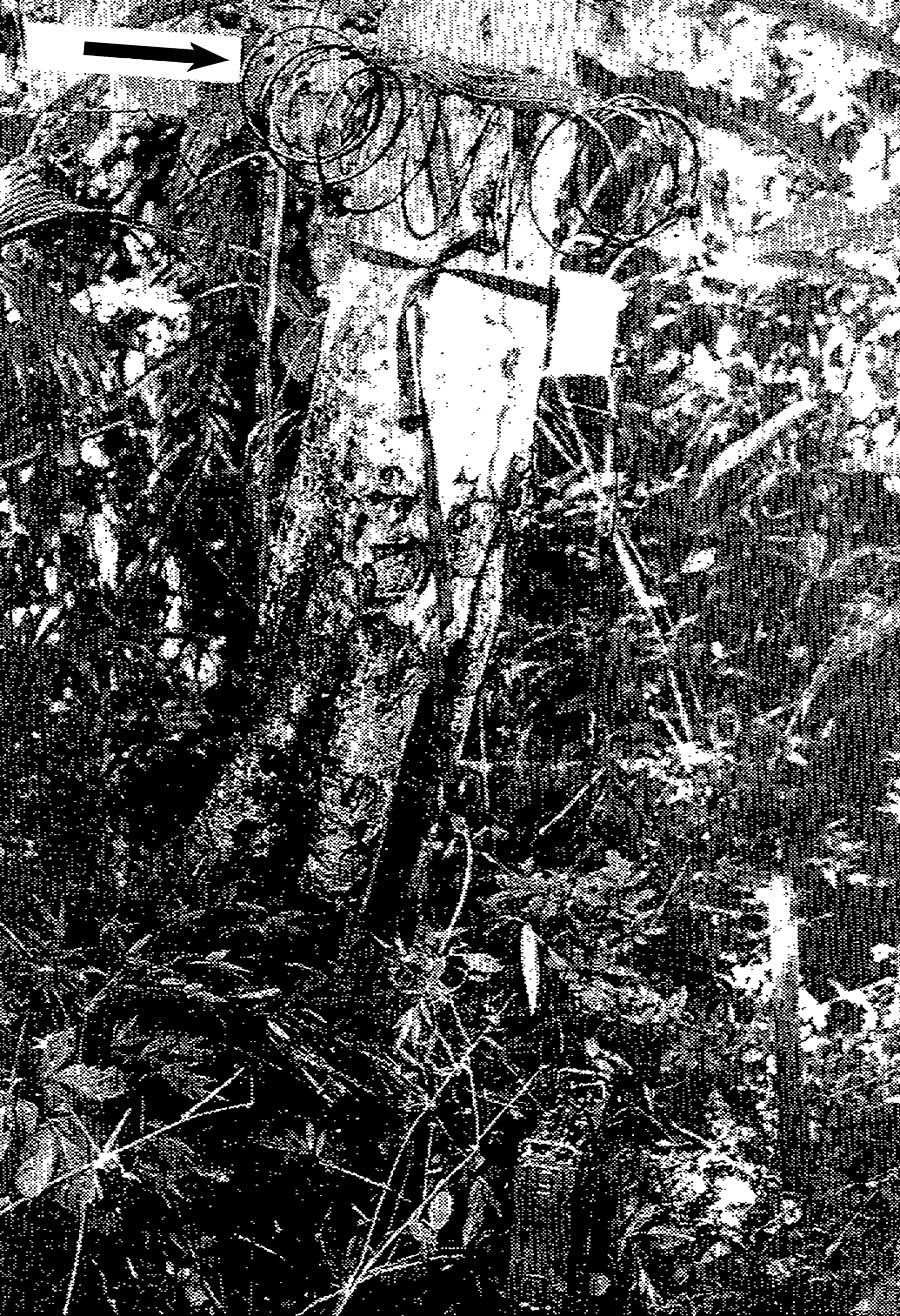

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: The Wiederin bookshop in Innsbruck, Austria; photo by

[Image: The Wiederin bookshop in Innsbruck, Austria; photo by  1)

1)  3)

3)  5)

5)  8)

8)  10)

10)  14)

14)  17)

17)  19)

19)