I’ve been reading Christopher P. Heuer’s book Into the White. It looks at how the landscape and climate of the far North—the Arctic—threw the European imagination into a bit of a tailspin, presenting a kind of non-configurable problem that shut the operating system down, often leaving ship-bound humans bereft of words and struggling to create comprehensible images.

Early on in the book, Heuer describes journeys of Arctic exploration as “a confrontation with conditions that simply did not fit into European schemes of pictorial composition, space, selfhood, and communication.” Indeed, what Europeans saw there could not even be described in terms of similar landscapes back home—because there were none, Heuer writes: “being like nothing else, the Arctic regions confounded literary strategies of analogy.”

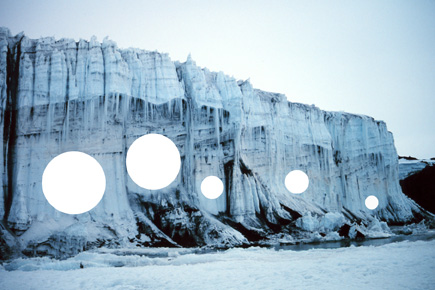

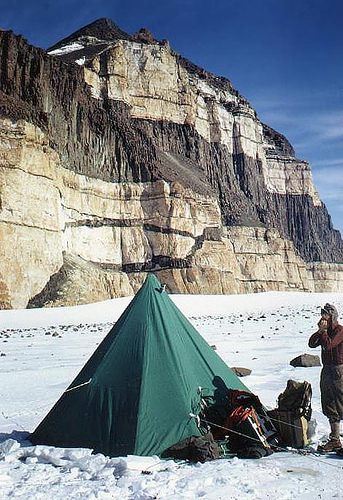

Frigid seas with no permanent land forms; drifting icebergs without clear shape or scale, constantly fragmenting into smaller masses and thus resisting the most basic concepts of counting and quantification; vast snow fields in places like Greenland and Canada where techniques of mapping and surveying broke down, and where—lacking visual features beyond sheer, endless whiteness—the burgeoning art of perspectival representation became impossible. Fathomless expanses of open water where alien hulks of ice, obscured by fog, drift through.

[Image: “The Sea of Ice” (1823-1824), Caspar David Friedrich.]

[Image: “The Sea of Ice” (1823-1824), Caspar David Friedrich.]

Often unable to sketch, describe, or explain what they saw there, European crews often left these bizarre and frightening experiences undocumented—as if an experience or situation can be so otherworldly, you cannot even describe it. No coordinate points, no baselines, no solid ground. (Of interest here would also be the work of expeditionary art historian William L. Fox, who has suggested that the Antarctic is equally challenging to human representational practices to the point of resisting human cognition itself.)

One of the most provocative aspects of the whole book for me is its implication that interstellar navigation, beyond planetary bodies, will pose similar—though certainly far more intense—challenges to human cognition, mapping, language, and measurement. This difficulty would presumably not be limited to the European imagination, of course, but to the terrestrial one. (Although it does raise the strange prospect that humans from Arctic regions could be the savviest interstellar navigators.)

In any case, Heuer’s book also points out that European expansion into vast new terrestrial regions, such as the Arctic and the South Atlantic, not just for scientific documentation but for “corporate resource exploitation,” as Heuer describes it, began just as perspectival representation was being developed in Renaissance Italy. That is, just as Europeans were attempting to conquer the infinite void of abstract architectural space through a series of mathematical grids and vanishing points, other Europeans were sailing off into novel terrestrial environments that resisted those same techniques, where the concept of scale itself broke down.

Hidden within this is perhaps a comment on art and commerce as equally concerned, in their own very different ways, with describing quantities beyond calculation—sheer plenty, limitless reserve, infinite exchange.

This leads to another of Heuer’s historical points—albeit one that, to me, reads more like coincidence than causation, but is nevertheless stunning in its visual power.

[Image: “Interior of Saint Bavo, Haarlem” (1631), Pieter Jansz, Saenredam; courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.]

[Image: “Interior of Saint Bavo, Haarlem” (1631), Pieter Jansz, Saenredam; courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.]

Heuer writes, at some length, about how iconoclasm was surging through Western European churches at the time, with the effect that the same nations that were sending mariners out to map and exploit distant environments were also convulsing at home with the widespread destruction of religious imagery. He draws a wonderfully surreal comparison here between white-washed church interiors, denuded of their statues and ornamentation by iconoclasts, and the huge, featureless super-objects of the Arctic, the vaulted spans of icebergs loose on the waves, the looming glacial cliffs of Greenland, the apparently empty wastes of northeastern Canada.

This seems to suggest that iconoclasts painting church interiors white were psychologically of a pair with distant ships’ crews landing in all-white lands, sailing into all-white fog banks, gazing fearfully upon all-white ice, as if the interiors of European churches had become their own sort of Arctic but also that the Arctic had taken on the terrible, sublime dimensions of a religious experience, a theological encounter with the iconoclastic void. A fathomless void, an immeasurable drift.

So, contrary to Heuer’s own claim of Arctic landscapes “being like nothing else,” they were, in fact, like iconoclastic church interiors.

Nevertheless, again, this seems more like a historical coincidence to me—albeit a highly provocative one—than anything like cause and effect.

In fact, it might be fruitful to reimagine Heuer’s observation as the basis of a novel—or, for that matter, as the structure of a Terrence Malick film. A father, consumed with rage against the church, rallies with his compatriots to raid the interiors of cathedrals, stripping them of anything that represents the divine, decapitating statues, shattering windows, painting frescos white, endless white, everything white; even as his son, a mercantilist, perhaps angry with the world itself, on a quest for life-affirming capitalist novelty, sets sail into the Arctic, discovering—instead of abundance and plenty—a world exactly like that created, in acts of rage, by his father. Endless white, lacking in features, silenced of music. A void.

We are left, as our story comes to an end, staring into an expanse that suggests almost no visual difference between cataracts of ice looming over the son’s ship, lost in the Arctic, doomed, and the eerie, seemingly immeasurable interior of a church brutally whitewashed by a God-obsessed father.

Of course, these characters should probably be reversed: it is the parent who is mercantilist, looking for a life of material improvement and capitalist profit, setting sail in the name of imperial, corporate exploitation, while the child stays at home, consumed with new fundamentalisms, painting over images of the past out of a mistaken belief that negation itself is enough for societal rebirth and personal self-discovery.

Either way, both characters are left not cataloging new forms of significance or abundance, but in a world devastatingly whitewashed of meaning.

Anyway, Heuer’s book is interesting and worth a read. It has also achieved the seemingly impossible, which is that it has made me genuinely excited to read Erwin Panofksy again.

[Image: Tar pushes up through cracks in the sidewalk on Wilshire Boulevard, near the La Brea Tar Pits; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Tar pushes up through cracks in the sidewalk on Wilshire Boulevard, near the La Brea Tar Pits; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: A makeshift system for capturing the near-constant tar and liquid asphalt leaking up from below a building near Lafayette Park; photo by

[Image: A makeshift system for capturing the near-constant tar and liquid asphalt leaking up from below a building near Lafayette Park; photo by  [Image: Liquid asphalt leaking upward into the parking lot of a Los Angeles karaoke club; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Liquid asphalt leaking upward into the parking lot of a Los Angeles karaoke club; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: The Baldwin Hills old field; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: The Baldwin Hills old field; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Screen grab from

[Image: Screen grab from  [Image: Flames burn through cracks in the sidewalk; screen grab from

[Image: Flames burn through cracks in the sidewalk; screen grab from

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

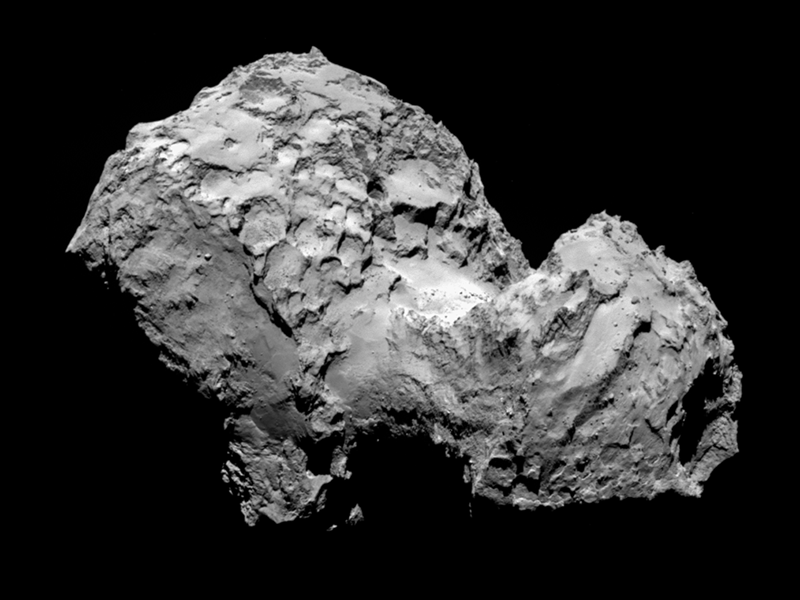

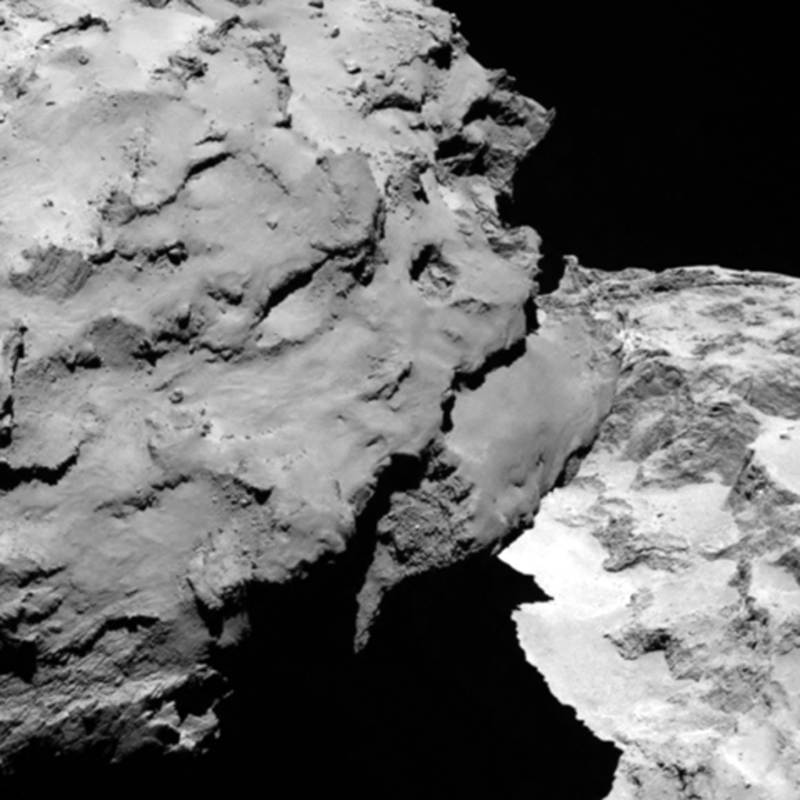

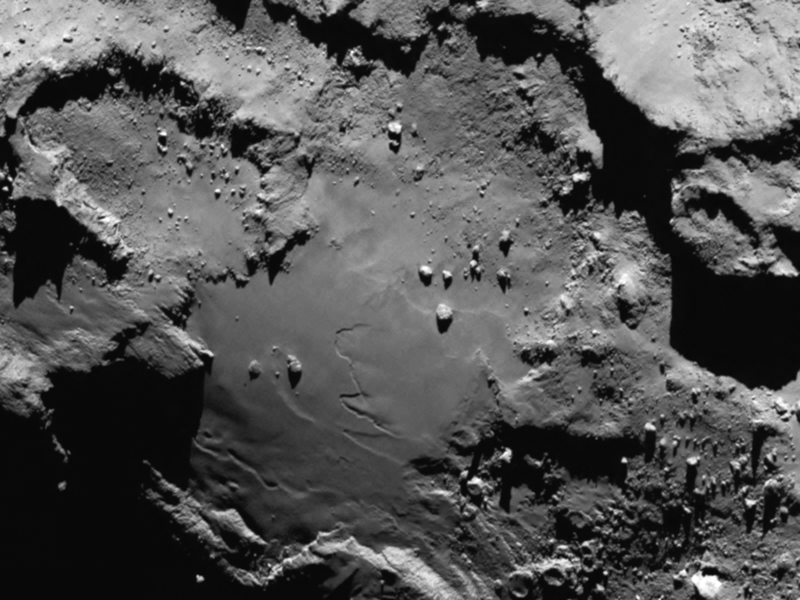

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

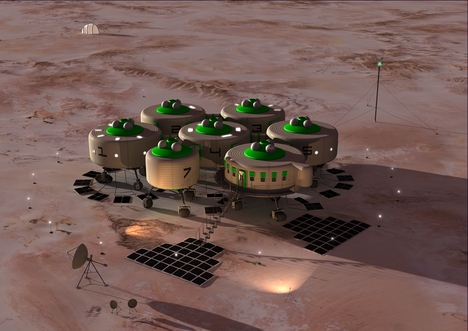

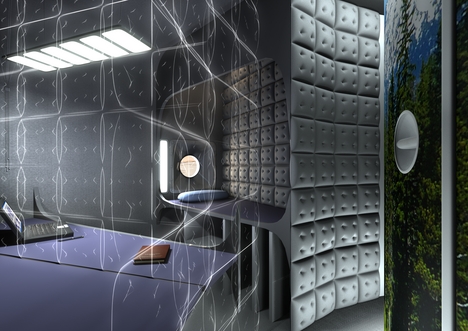

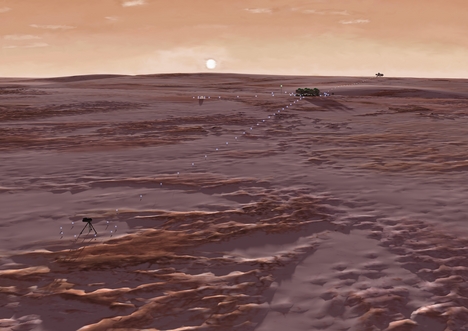

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the  [Image: ANY Design Studios, via

[Image: ANY Design Studios, via  [Image: ANY Design Studios, via

[Image: ANY Design Studios, via  [Image: ANY Design Studios, via

[Image: ANY Design Studios, via

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via  [Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via

[Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via  [Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from

[Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at  [Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at