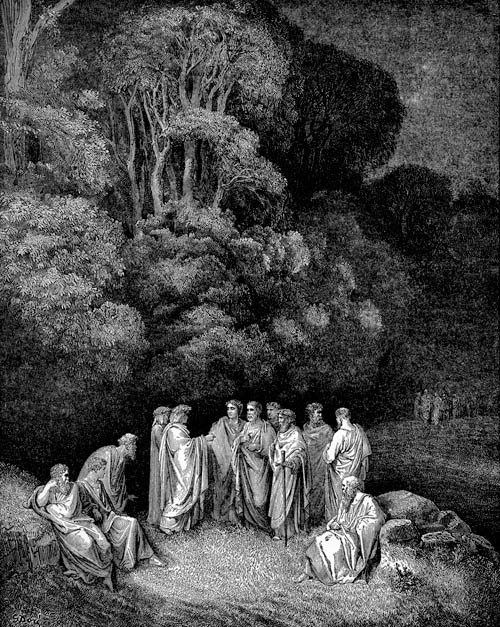

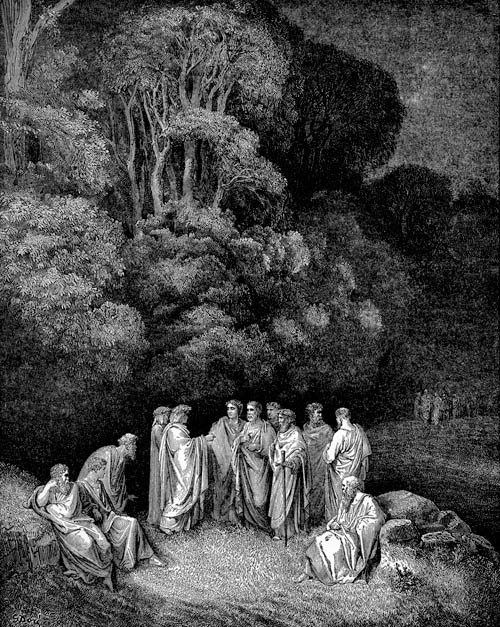

[Image: “Homer, the Classic Poets,” by Gustave Doré, from Canto IV of The Inferno].

[Image: “Homer, the Classic Poets,” by Gustave Doré, from Canto IV of The Inferno].

Novelist Zachary Mason’s Lost Books of the Odyssey has been described by The New York Times as “dazzling… an ingeniously Borgesian novel that’s witty, playful, moving and tirelessly inventive.”

As Slate’s John Swansburg describes it, the book is a fictional anthology of “Homeric apochrypha—versions of the Odysseus story that circulated in the time before Homer but were left out of the epic as we came to know it.” Yet “Mason’s enterprise never devolves into a mere high-concept exercise,” Swansburg adds. And I agree: the book’s constantly shifting short narratives offer a kind of stratigraphic road-cut straight to the contested origins of Western mythology, where a storm-wracked, war-torn archipelago is ceaselessly crossed by a homesick husband fighting to return to his family—only Mason has taken these elements and cross-wired them, creating a dreamlike, parallel landscape of new heroic sequences, echoes, and myths.

In the following interview, Zachary Mason speaks to BLDGBLOG about his book; its use of the archipelagic landscapes of ancient Greece for new, combinatorial ends; the algorithmic templates underlying much of his fiction; his current work on Artificial Intelligence; the future of automated construction technologies, including 3D-printing, a theme explored in Mason’s most recent work; other possible narrative directions for further rewritings of The Odyssey (including a version set in the Caucausus Mountains, with, as Mason describes it below, “a huge system of unreliable, unmapped and essentially creaky rope-bridges strung up between the peaks”); and much more. We spoke by phone.

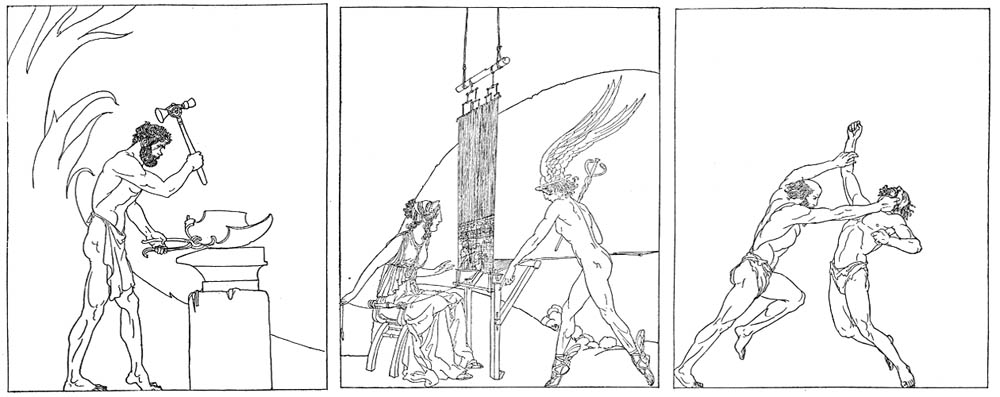

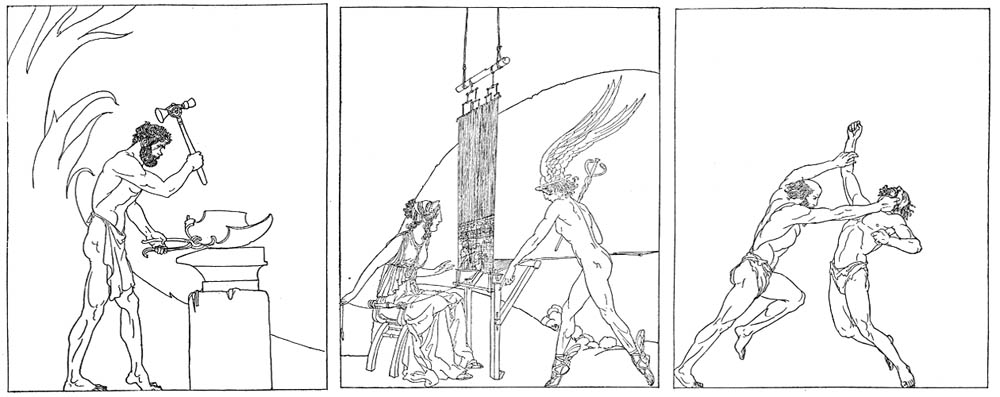

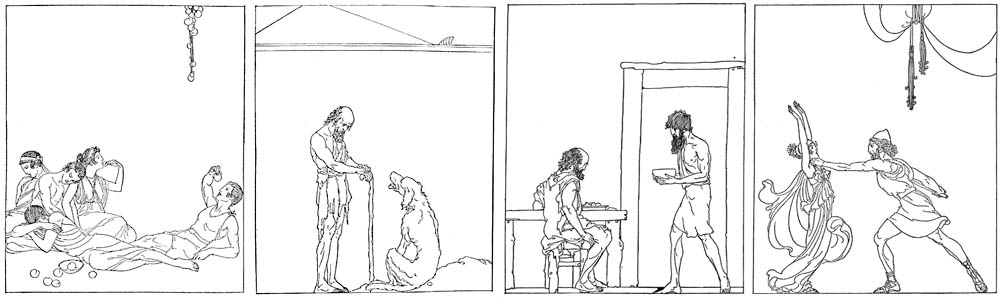

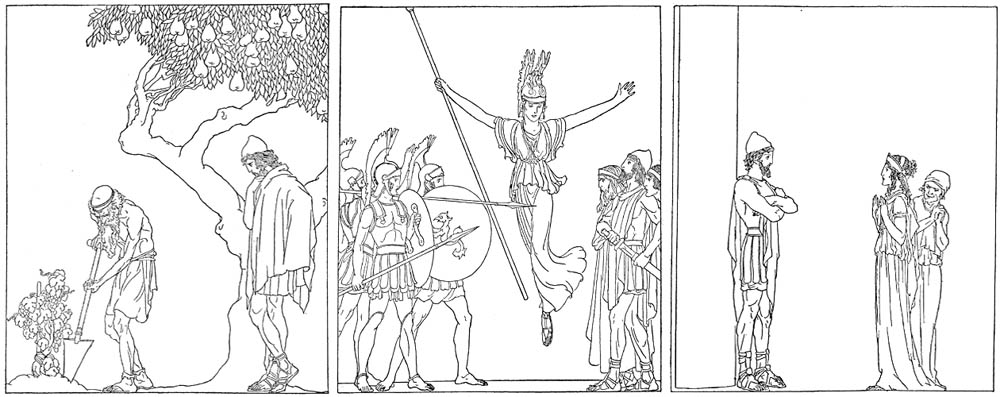

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s own retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s own retelling of The Odyssey].

• • •BLDGBLOG: I’d like to start with one of the most memorable images in the book, that of “

Agamemnon’s Fortress.” Could you describe that briefly?

Zachary Mason: In that chapter, the Greeks, having no building materials except for the timbers of their ships, and expecting the siege to last a long time, have excavated their forward base in the sand in front of Troy.

This chapter has the structure of a fairy tale, or something out of the Arabian Nights. It starts with Agamemnon’s sense of helplessness; for all his armies and his heroes he can’t take a single city, which leads him also to reflect on the extent of his ignorance, so he calls together his three wisest counselors and, not being one for half-measures, asks them to explain, essentially, everything in the world. Three times he asks them, and each time they come back with a denser and perhaps pithier solution, and with each iteration more time passes.

The underground base becomes first a city, then a network of cities, that keep getting deeper as the old cities crumble and are used only for storage chambers and secret passages, and, all this time, Troy is only about half a mile away. By the end of the story Troy has been abandoned, so there’s no further reason for the Greeks to be there, but they still are, and they’re still digging deeper.

Part of what I was doing was taking the structure of a fairy tale—often there are three questions, animals, obstacles or what have you—and making the progression between the iterations exponential, rather than constant, so there’s a drastic acceleration.

Also, there’s something fascinating about this improvised, temporary, and quite uncomfortable underground base becoming permanent and entrenched, and going ever deeper, starting to dominate the lives of the residents with its deranged logic. It’s reminiscent of an ants’ nest, or the World War II eras quonset huts still in use at SRI.

BLDGBLOG: Or Kafka’s “Burrow“, another story of tunneling. What I like about the image is its dichotomy between the aboveground walled fortress of Troy, with its stone walls and permanent streets and houses, and its long-term sense of history, compared to the underground maze of the invading Greeks, constantly turning this way and that and digging deeper into the earth. It’s a nice juxtaposition.

Mason: Troy is the absence of possibilities, in a sense; it’s just there and the Greeks can’t do anything about it, no matter how much they try. In the sand, though, there are infinite possibilities, all of them fairly useless.

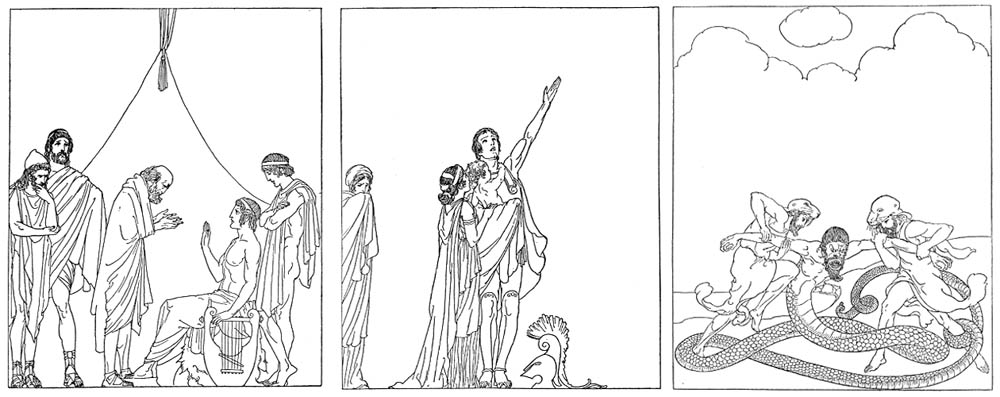

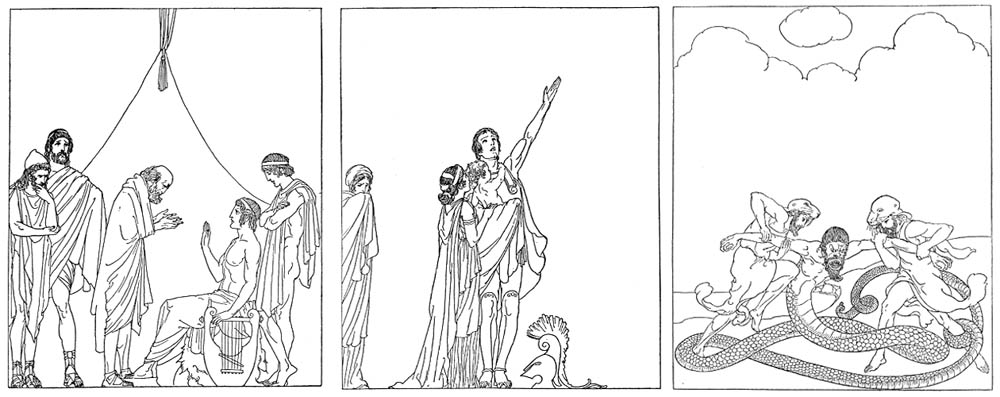

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: You also describe how, when the sand walls collapse, the Greeks implement laws that say the soldiers can’t excavate or uncover things that have been buried. They’re forced to avoid their own past, in a sense, and keep digger new tunnels. It’s like a legislatively enforced amnesia, or a living archive that refuses to excavate itself.

Mason: I liked the idea that they would become trapped by their own superstitions: prevented from doing the rational thing—as far as planning went—and obliged by this unfortunate belief to keep digging themselves in deeper.

In a way, it’s the opposite of amnesia, if you think of the collapsed chambers as preserved. As though we were forbidden to repair collapsed or damaged buildings on the surface, and cities become theme-parks of stratified decay.

BLDGBLOG: There’s another image in the book that really caught me: Ilium, “death’s city,” full of “uncountable mausoleums” and constructed from bones. “The high walls of Death’s city became the ubiquitous background of the Greek’s dreams,” you write.

Mason: In that chapter Troy has become Death’s city, and it is implied that all of Hades is contained within its walls. I imagined Death’s city as a place of levels, reaching down forever; it goes so deep, that not even its inhabitants have seen all of it, which somehow seems to gel with the way the representation of Death as an object of obsessive focus.

In this story, Menelaus eventually defeats and overthrows Death, and though he intends to destroy his city, but he end up doing no more than taking Death’s place, and adding new levels to the already infinite levels of the city.

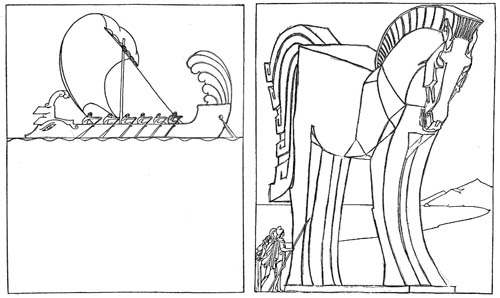

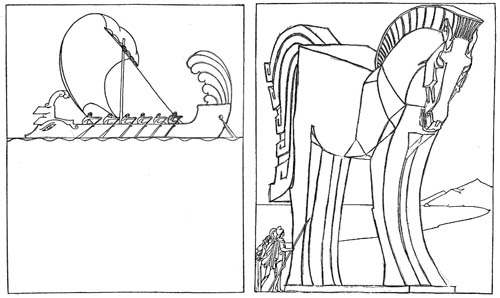

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious, pulling back a level, how a particularly evocative city description or landscape description can, in and of itself, achieve something on a narrative level that other rhetorical devices often aren’t able to or have a harder time accomplishing. It interests me, for instance, that if your book was set in a very different place or geography—in central Illinois, say, wandering from town to town—those facts alone, before characterization even kicks in, would hugely affect the mood or tone of the story. Part of the imaginative appeal of The Odyssey itself, I would say, has a lot to do with the archipelagic landscape it takes place within; if Odysseus had just wandered around the Caucasus Mountains, from peak to peak, instead of island to island, then the story’s cosmic overtones—wherein each island is its own micro-cosmic world, with its own sequences of experience—would have been achieved only in a quite different rhetorical way.

Mason: [laughs] I’m imagining The Odyssey set in Illinois—how the Trojan War would be a fight for one particular bit of plain amidst otherwise completely identical expanses of plain, and how that would add a sense of futility to Odysseus’s homeward journey—he weeps when he finally sets foot on Ithaca, which is fifty hectares of absolutely undistinguished farmland.

Here’s an idea: set The Odyssey in the Caucasus, but with a huge system of unreliable, unmapped and essentially creaky rope-bridges strung up between the peaks. The valleys are full of bandits, and hardship, and take a long time to navigate—but, though the ropes are faster, no one knows quite why they’re there, or their connectivity. Then you’d have something that feels at least a little like The Odyssey.

A nice thing about islands, as opposed to regular old landscape, is that they seem completely knowable. With an island, one could have a clear view of all of the elements in play in whatever narrative, and of the island’s history, and of the full significance of everything. One’s understanding of a continent is necessarily hand-wavey, and things are probably changing faster than one can keep track of them.

There was an older version of the Lost Books—or, at any rate, another book that ended up getting folded into what eventually became the Lost Books—which was going to be much more explicitly geographical. Every story was going correspond to an island, and the elements of those islands would be specified by a combinatoric system. I made up a table of elements, and I was duly working my way through the possible combinations, but it turned out to be very, very difficult to make this work; I couldn’t finish it, though you can still see echoes from time to time.

I think art tends to turn out best under moderate constraint; the combinatoric system was probably a little too strong. But I kind of like the way the character of the old, never-quite finished book shows up in the Lost Books (there’s actually more than one unfinished ghost-book lurking in the Lost Books), because its interesting when there are multiple patterns that partially describe, in this case, a book, but where none of them completely describe it. Its a little like complexity theory—too much order and you get banal rigidity, but too little and you get chaos, and the interesting things are on the boundary between the two.

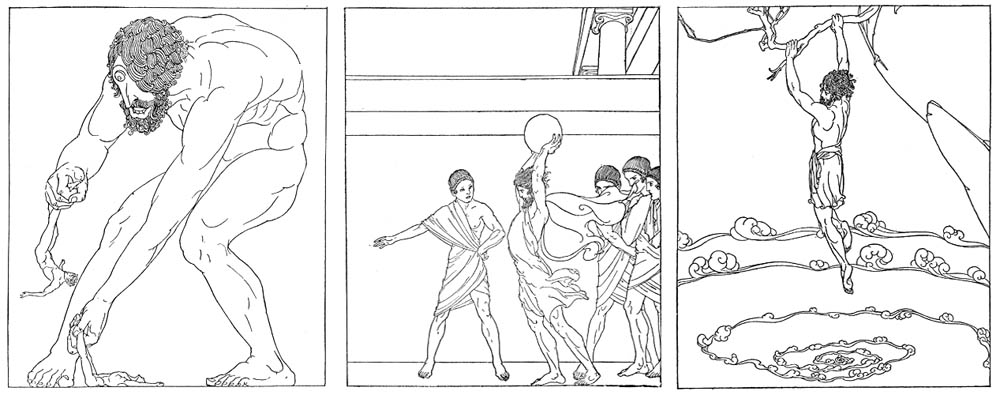

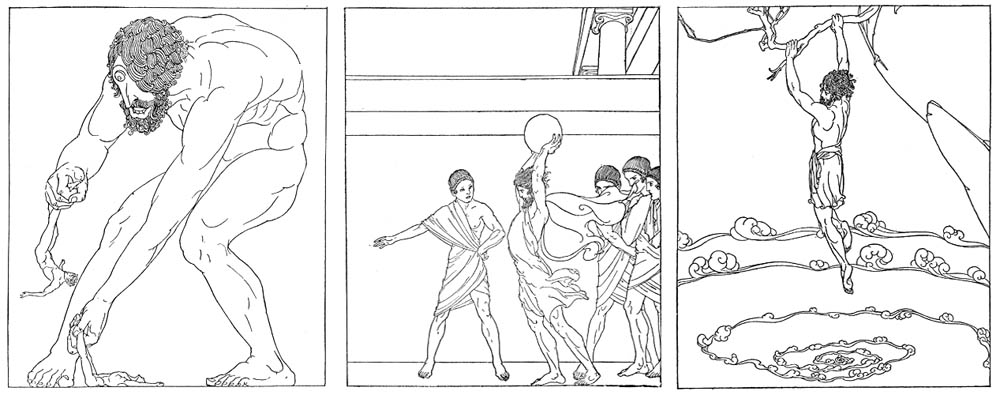

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Are you drawn to things like the Oulipo, or other sorts of literary games?

Mason: I’ve always been drawn to Oulipo. I have one life in math and science, and another in literature, so Oulipo is compelling as the intersection between the two. On the other hand, Oulipan games don’t always work. There are a few products of Oulipo that are brilliant, and some that are interesting, and more that are the literary equivalent of musical scales.

The book was, in its original conception, intensely Oulipan, but I couldn’t get it work that way, so I ended up relaxing the constraints I had imposed on myself, lest I end up with something that felt like a sterile exercise rather than an organic whole.

So you might say that, for me, Oulipo is a good starting point but not a good finishing point.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Is the final sequence of chapters arranged for narrative effect, then, or is it based on some other sort of underlying structure or combinatorial path?

Mason: In an early version of the book I did use an algorithm to order the chapters. In those days, each chapter was associated with a handful of keys—broad themes like “time” and “the gods” and “revenge” and so forth. I wrote a program that used simulated annealing to order the book in a more-or-less optimal way, where optimality was defined as maximizing the number of overlapping keys between adjacent chapters. The intent was to produce an ordering where there was always a strong sense of continuity between chapters, but where the nature of that continuity varied with every boundary.

In the end, I didn’t like the ordering the algorithm produced, and realized that there were actually other rules I wanted to follow, some of which didn’t lend themselves to formalization, so I ended up arranging the chapters by hand. I try to alternate long and short chapters, and its good when adjacent chapters rhyme, thematically; also, the book now starts off by establishing the kind of recombinatoric game I’m playing with The Odyssey, and then, as you get toward the end, that pattern breaks down, and you get all sorts of strange things—The Odyssey interpreted as a chess manual, for instance.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: The chess manual chapter—“Record of a Game”—is fantastic. Could you describe that chapter briefly and explain its conceit?

Mason: “Record of a Game” is a chapter that explains how The Iliad is not, in fact, an epic, but an ancient chess manual. This chapter explains that chess radiated out from India and took on locally idiosyncratic forms in most Indo-European cultures; in ancient Greece, it assumed a form in which the pieces, rather than being faceless icons, are strongly individuated. There were a few particular games that were considered to embody everything that was worth knowing about the game, and chess masters had to memorize those games precisely. Various mnemonics were added to make this task easier and eventually, to the uninitiated, the records of these games came to seem like heroic narratives, which was aided when the mnemonics were misinterpreted as epic clichés—Thetis being “trim-ankled,” Achilles “fleet-footed” and so forth.

A lot of the book is about interpreting The Odyssey as a code, so that Homer’s text is understood as a distortion of some underlying signal, and it is that signal, under various assumptions, that one is trying to infer. “Record of a Game” is perhaps the most extreme example of this, in that it explains away almost everything about The Iliad.

The coda to this chapter explains that The Odyssey is a sort of fictive chess manual, describing the motion of the pieces after the game has finished and the players have departed, in which the Odysseus piece is trying to get back to its home square. So it a sort of second-order game.

BLDGBLOG: Interpretation, here, becomes a form of paranoia—more an act of invention than one of reading.

Mason: There are some aspects of The Iliad that lend themselves almost eerily to this kind of interpretation—like the famous catalog of ships, which is also famously boring. In “Record of a Game,” it’s explained that the catalog of ships is properly understood as a description of the opening in a chess game.

Then there are all the lists of killing—this warrior slew that warrior, and that warrior slew this other warrior—which is not, I think, hugely interesting in itself, but, if you look at it as a series of exchanges in the middle game, begins to make sense sense.

On the other hand, Homer has been what one might call exhaustively interpreted. You can sit alone in your living room and make up the craziest, most implausible theory about Homer that you can, and then go to Google, you’ll find that some serious person with solid academic credentials has dedicated his career to espousing your preposterous theory.

BLDGBLOG: [laughs] Like Shakespeare wrote Homer.

Mason: Exactly.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: If that’s the case, do you see your own book as participating in, and thus continuing, this sort of interpretive culture? Or is it more of a parody?

Mason: It’s a bit of both. I was certainly aware of the exhaustive interpretation of Homer, and I guess I thought of the Lost Books as enabled by that, and somehow setting a cap on it, by being the logical culmination and maximum expression of this tendency. It’s as though I was saying, “You call that interpretive chaos? I’ll show you interpretive chaos!”

That said, I wasn’t trying to put Homeric interpretation out of business or make any big, stomping academic points. It just seemed like this tradition both suggested and licensed a really fun thing to do with the book.

And then, The Odyssey seems to lend itself uniquely to this kind of remixing, in that it’s compelling at almost any granularity. The way its written is compelling in the details, but, at a coarser level, what one might call its language of imagery is powerful. The Odyssey retains considerable power even when reduced to a plot synopsis, which isn’t true of many books—a plot synopsis of The Inferno or Lolita is unlikely to be hugely interesting. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road might come close, but, really, it just has a single image. As I say this, it occurs to me that many Borges stories would still be compelling as a single paragraph precis.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: Stepping back a bit, your author bio refers to you as an Artificial Intelligence researcher, but I’m curious what that actually means.

Mason: The first thing to notice about AI is that there isn’t any; in some sense, there’s been no real progress in the field. We don’t know much more about the computational character of cognition than we did in 1950. So I, like a number of people, am interested in trying new ways of approaching the problem. New kinds of computational models of perception and language are, I think, one promising path.

A particular interest of mine is computational models of design. Design problems are kind of a sweet spot, insofar as they offer deep domain richness, but they don’t too much background knowledge, which is very difficult to handle, computationally. You just need models of artifacts, and the way those artifacts are interpreted.

One of the problems with A.I. is that interacting with the world is really tough. Both sensing the world and manipulating it via robotics are very hard problems, and solved only for highly stripped-down special cases. Unmanned aerial vehicles, for instance, work well because maneuvering in a big, empty, three-dimensional void is easy—your GPS tells you exactly where you are, and there’s nothing to bump into except the odd migratory bird. Walking across a desert, though—or, heaven help us, negotiating one’s way through a room full of furniture in changing lighting conditions—is vastly more difficult.

BLDGBLOG: Saying this purely as a dilettante, it seems like there are at least two models of Artificial Intelligence. One of them is about spatial navigation, as you say, but another is more textual, or language-based. This latter version touches on things like the Turing Test, of course, but also on things like the text-mining industry, where they’ve developed intelligent software programs that can read through hundreds of thousands of pages in a flash and find the keywords or phrases that you’re looking for—which is different from a Google search.

Mason: Text-mining is well and good, but there’s a sense in which it’s not A.I. The programs don’t understand the text in any meaningful way. They manipulate it statistically, and, in that way, they’re able to accomplish things that appear intelligent—but there’s no actual comprehension.

You can take text analytics and that sort of thing up to a certain point, and you can get some pretty impressive results—Google works well—but there’s a hard boundary that you’re not going to be able to cross if you don’t have a full-fledged model of cognition.

Nobody’s figured out how to make that model, so there are hard limits on how far things like Google and text analytics can go. This is tacitly understood, for the most part (though I’ve spoken with some Googlers who have seemed guilty both of hubris and of not understanding A.I.’s history), but it’s bad business to admit it. So, when they say their algorithms are intelligent, or that their algorithms understand the text and so forth, its just fatuous marketing-speak.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious how all this comes together in The Lost Books of the Odyssey. So far, we’ve talked about combinatorics, allegories, Artificial Intelligence, and the Oulipo, and I know that, for me, there were moments while reading the book when it felt almost as if a program had been fed certain narrative parameters—cave, cyclops, Odysseus, boat—and the remixed results became the Lost Books, as if it were the output of a demented A.I. program. Were you hoping to use the book itself as a model for computational literature?

Mason: There was a time in my life when I would have been very happy to have it suggested that my work was the output of a demented A.I. program—

BLDGBLOG: I meant that in a positive way!

Mason: A counter-question for you is: do you think you would have thought that if my bio hadn’t said that I worked with A.I.?

BLDGBLOG: Perhaps not. But, on another level, especially with a book like yours, doesn’t the author bio become a deliberate way to frame the book’s contents? It helps to flavor how a book is received and interpreted.

Mason: That’s a fair point. In fact, in the first edition of the book, I used a fake author bio. I claimed to be an archaeo-cartographer and paleo-mathematician at Magdalen College, Oxford, the holder of the John Shade Chair. Note that archaeo-cryptography and paleo-mathematics don’t exist as disciplines, and John Shade is a character in a Nabokov novel. I was perhaps unreasonably pleased with this trick, not least because much of the book is about endless recursions of false and manipulative identity—so it seemed to fit, rather than being arbitrary hijinks.

I was persuaded to use a real biography for the FSG edition, and have since regretted it. My author-bio says I do A.I., because I thought it was an interesting hook, but it seems to color the way people approach the book now, and not necessarily in desirable ways. On the whole, I’d like the book to be read without reference to my biography. Perhaps I should really have gone beyond the bounds of the plausible and claimed to be a graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, and that I now teach creative writing at a small Midwestern liberal arts school.

I’ve been sufficiently cranky about this that I’ve considered saying that, in fact, I’m just a writer, but there’s another guy with the same name as me who is a computer scientist specializing in A.I. We met because we have similar gmail addresses, and sometimes get each other’s mail. He was kind enough to read an early draft of my book, and, being a Borges fan, like disproportionately many well-read scientists, wondered how differently the book would read if it had been written by an A.I. guy. I thought that sounded like a good hook, and ran with it.

But, to answer your question more directly, I certainly wasn’t going for anything overtly combinatoric, or at least not after the book’s very earliest days.

It sounds like you’re reacting to my preoccupation with what I might call the primes of the story. There are aspects of the Odyssey that seem essential, and these are few in number, just a handful of images. There’s a man lost at sea, an interminable war a long way behind him, and a home that’s infinitely desirable and infinitely far away. There’s the man-eating ogre in his cave; there are the Sirens with their irresistible song; there’s the certain misery of Scylla and Charybdis.

I feel like these images are responsible for the enduring power of the story, and its survival, more than the particular details of, say, dialogue among the suitors, or what have you. I wanted to work directly with these primes, to present them in as powerful and stripped-down a way as possible, and to explore how they could interact, and how they could combine to make new forms. I suppose this kind of minimalist, reductive aesthetic does has a mathematical flavor.

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for The Adventure of Odysseus and the Tale of Troy, Padraic Colum’s retelling of The Odyssey].

BLDGBLOG: In the more recent fiction that you sent me, you’ve been exploring quite strong architectural and urban imagery. I’m curious to hear more about how urban imagery, in particular, features in your more recent fiction, and other ways that urban and architectural descriptions are being foregrounded in your work.

Mason: I sent you some fragments of a book, tentatively titled Void Star, in which architecture does feature rather prominently.

The book is set in the murkily indefinite future. Technology has improved, and robotics works much better, so much so that it has become a cheap, boring technology, and construction robots, in particular, are ubiquitous—they’re essentially 3D printers scuttling around on insect-like legs. Right now, researchers are taking the first steps toward building robots where you can set them loose and they’ll assemble complicated structures—often, interestingly, mimicking the control principles used by social insects—and I thought how interesting it would be, and how different the world would look, if these things ever actually work.

Today, anybody can go to Home Depot or its equivalent and buy the materials to build a shed; but construction, on a large scale, is very expensive and reserved for wealthy organizations. It’s a rare privilege to actually get to build something. If these robots exist, then architecture is democratized: anyone with a few bucks can build a structure to whatever specifications they like.

Once you have that, cities start to metastasize and grow. Favelas and other improvised and illegal shadow cities become marvelous, growing layer upon layer, like coral reefs.

Another architecturally salient aspect of Void Star is that, in the book, A.I.s exist, but they’re not like anyone expected. They’re intelligent but not human; in fact, their minds and perspective and languages are so different that people can’t really talk to them—they’re much more like Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris than Commander Data, the Terminator, Agent Smith, or HAL. Despite this, they can still be useful—in design tasks, for instance. They write most of the world’s software, and do it very quickly—the amount of code in the world increases by many orders of magnitude, but nobody knows how it works. Software development becomes a process less of hacking code than establishing some sort of shared understanding with these strange, essentially foreign intelligences.

The A.I.s also design buildings, and they think so fast, and with such breadth, that their designs are more complete than is otherwise possible. Buildings become much more complicated, and better thought-out—in a sense, absolutely thought-out. The A.I. might consider, say, the light and the acoustics at every spot in the building at every time of day and every day of the year, and the kinds of relationships that you could then create between the experiences at these different locations. Also, because the machines have such fine-tuned control of the way buildings are constructed, they can implement design motifs that go down almost to the molecular level. In buildings as they are, there is, inevitably, unarticulated matter—a girder is just a girder, concrete is just concrete—but the machines could make their artifacts fractally ornate at every level. They would, in some sense, be complete artifacts.

It will be an interesting world.

• • •Thanks again to Zachary Mason for taking the time to have this conversation. Pick up a copy of

The Lost Books of the Odyssey, meanwhile, which came out in paperback last month, and see what you think.

[Images: Hiking in Joshua Tree National Park; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: Hiking in Joshua Tree National Park; photos by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Joshua Tree National Park; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Illustration by

[Image: Illustration by  [Image: Wiring the ENIAC; via

[Image: Wiring the ENIAC; via  [Image: Wiring the ENIAC; via

[Image: Wiring the ENIAC; via  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Replicants in

[Image: Replicants in  [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté].

[Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté]. [Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté].

[Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté].

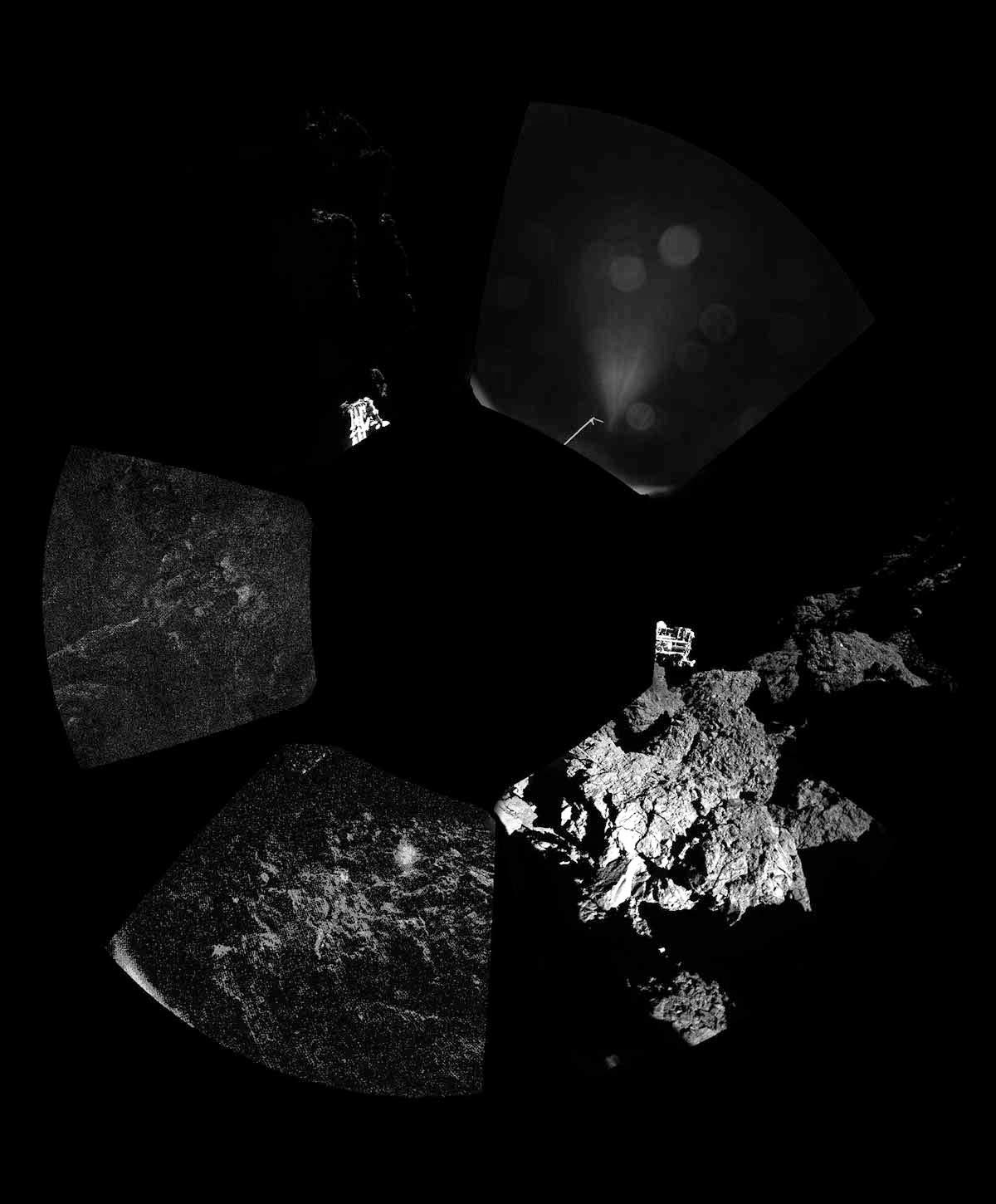

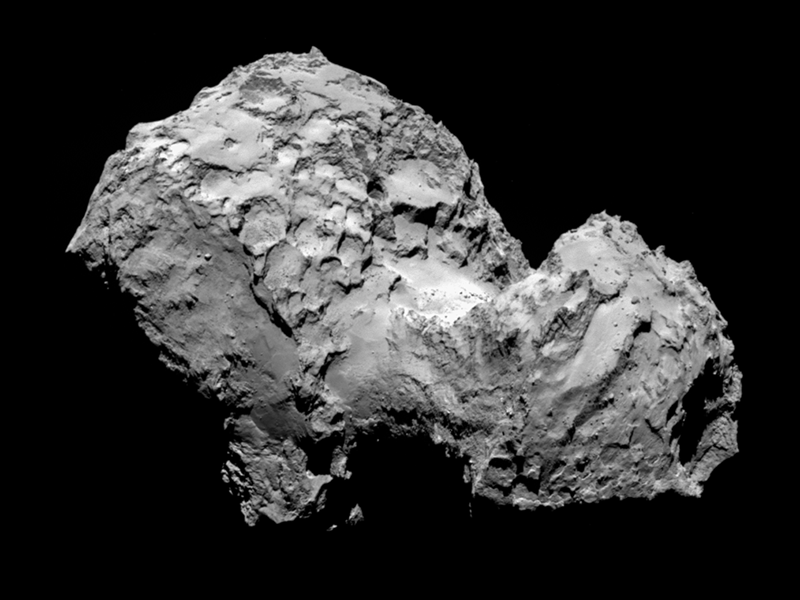

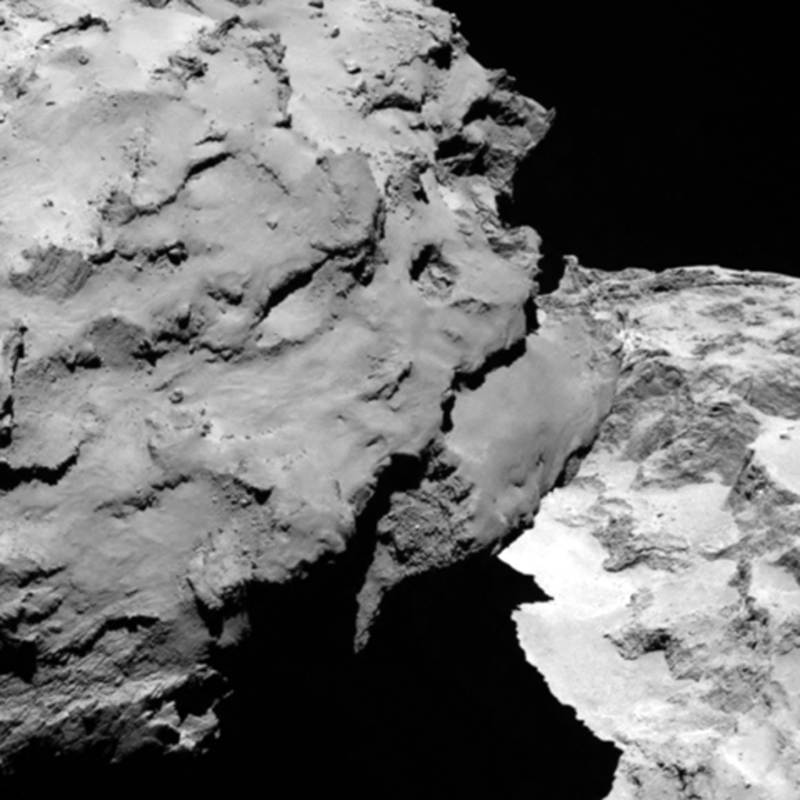

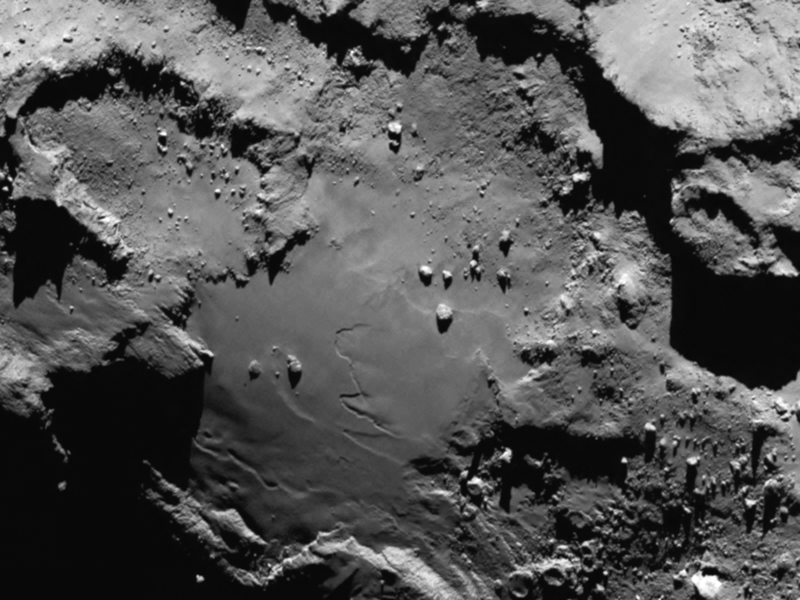

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

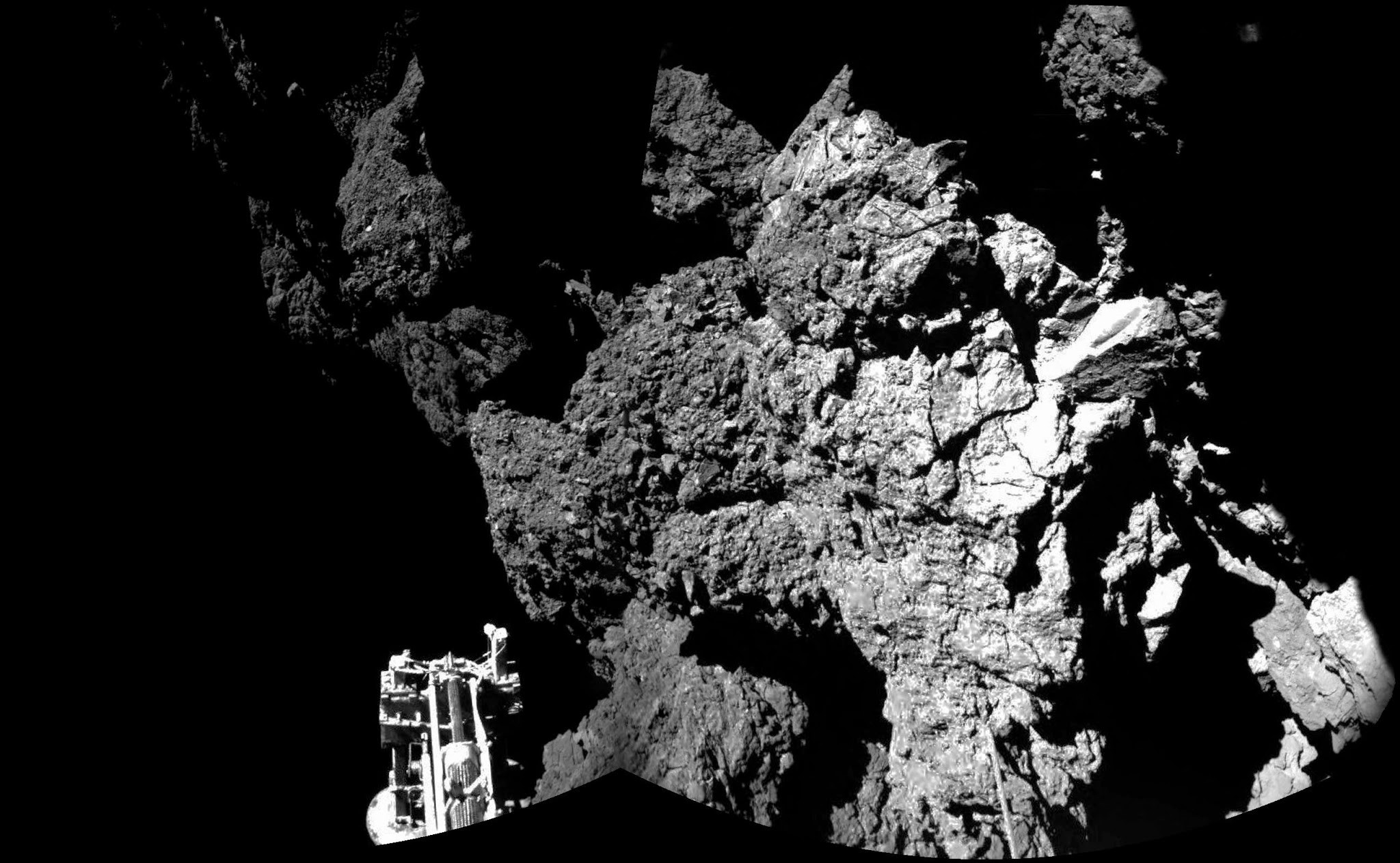

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via

[Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for  [Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for

[Images: Illustrations by Willy Pogány for