[Image: Galaxy M101; full image credits].

[Image: Galaxy M101; full image credits].

In a talk delivered in Amsterdam a few years ago, science fiction writer Alastair Reynolds outlined an unnerving future scenario for the universe, something he had also recently used as the premise of a short story (collected here).

As the universe expands over hundreds of billions of years, Reynolds explained, there will be a point, in the very far future, at which all galaxies will be so far apart that they will no longer be visible from one another.

Upon reaching that moment, it will no longer be possible to understand the universe’s history—or perhaps even that it had one—as all evidence of a broader cosmos outside of one’s own galaxy will have forever disappeared. Cosmology itself will be impossible.

In such a radically expanded future universe, Reynolds continued, some of the most basic insights offered by today’s astronomy will be unavailable. After all, he points out, “you can’t measure the redshift of galaxies if you can’t see galaxies. And if you can’t see galaxies, how do you even know that the universe is expanding? How would you ever determine that the universe had had an origin?”

There would be no reason to theorize that other galaxies had ever existed in the first place. The universe, in effect, will have disappeared over its own horizon, into a state of irreversible amnesia.

[Image: The Tarantula Nebula, photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope, via the New York Times].

[Image: The Tarantula Nebula, photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope, via the New York Times].

It was an interesting talk that I had the pleasure to catch in person, and, for those interested, it includes Reynolds’s explanation of how he shaped this idea into a short story.

More to the point, however, Reynolds was originally inspired by an article published in Scientific American back in 2008 called “The End of Cosmology?” by Lawrence M. Krauss and Robert J. Scherrer.

That article’s sub-head suggests what’s at stake: “An accelerating universe,” we read, “wipes out traces of its own origins.”

[Image: A “Wolf–Rayet star… in the constellation of Carina (The Keel),” photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope].

[Image: A “Wolf–Rayet star… in the constellation of Carina (The Keel),” photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope].

As Krauss and Scherrer point out in their provocative essay, “We may be living in the only epoch in the history of the universe when scientists can achieve an accurate understanding of the true nature of the universe.”

“What will the scientists of the future see as they peer into the skies 100 billion years from now?” they ask. “Without telescopes, they will see pretty much what we see today: the stars of our galaxy… The big difference will occur when these future scientists build telescopes capable of detecting galaxies outside our own. They won’t see any! The nearby galaxies will have merged with the Milky Way to form one large galaxy, and essentially all the other galaxies will be long gone, having escaped beyond the event horizon.”

This won’t only mean fewer luminous objects to see in space; it will mean that, “as a result, Hubble’s crucial discovery of the expanding universe will become irreproducible.”

[Image: The “interacting galaxies” of Arp 273, photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope, via the New York Times].

[Image: The “interacting galaxies” of Arp 273, photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope, via the New York Times].

The authors go on to explain that even the chemical composition of this future universe will no longer allow for its history to be deduced, including the Big Bang.

“Astronomers and physicists who develop an understanding of nuclear physics,” they write, “will correctly conclude that stars burn nuclear fuel. If they then conclude (incorrectly) that all the helium they observe was produced in earlier generations of stars, they will be able to place an upper limit on the age of the universe. These scientists will thus correctly infer that their galactic universe is not eternal but has a finite age. Yet the origin of the matter they observe will remain shrouded in mystery.”

In other words, essentially no observational tool available to future astronomers will lead to an accurate understanding of the universe’s origins. The authors call this an “apocalypse of knowledge.”

[Image: “The Christianized constellation St. Sylvester (a.k.a. Bootes), from the 1627 edition of Schiller’s Coelum Stellatum Christianum.” Image (and caption) from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

[Image: “The Christianized constellation St. Sylvester (a.k.a. Bootes), from the 1627 edition of Schiller’s Coelum Stellatum Christianum.” Image (and caption) from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

There are many interesting things here, including the somewhat existentially horrifying possibility that any intelligent creatures alive in that distant era will have no way to know what is happening to them, where things came from, even where they currently are (an empty space? a dream?), or why.

Informed cosmology will, by necessity, be replaced with religious speculation—with myths, poetry, and folklore.

[Image: 12th-century astrolabe; from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

[Image: 12th-century astrolabe; from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

It is worth asking, however briefly and with multiple grains of salt, if something similar has perhaps already occurred in the universe we think we know today—if something has not already disappeared beyond the horizon of cosmic amnesia—making even our most well-structured, observation-based theories obsolete. For example, could even the widely accepted conclusion that there was a Big Bang be just an ironic side-effect of having lost some other form of cosmic evidence that long ago slipped eternally away from view?

Remember that these future astronomers will not know anything is missing. They will merrily forge ahead with their own complicated, internally convincing new theories and tests. It is not out of the question, then, to ask if we might be in a similarly ignorant situation.

In any case, what kinds of future devices and instruments might be invented to measure or explore a cosmic scenario such as this? What explanations and narratives would such devices be trying to prove?

[Image: “Woodcut illustration depicting the 7th day of Creation, from a page of the 1493 Latin edition of Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle. Note the Aristotelian cosmological system that was used in the Middle Ages, below, with God and His retinue of angels looking down on His creation from above.” Image (and caption) from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

[Image: “Woodcut illustration depicting the 7th day of Creation, from a page of the 1493 Latin edition of Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle. Note the Aristotelian cosmological system that was used in the Middle Ages, below, with God and His retinue of angels looking down on His creation from above.” Image (and caption) from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

Science writer Sarah Scoles looked at this same dilemma last year for PBS, interviewing astronomer Avi Loeb.

Scoles was able to find a small glimmer of light in this infinite future darkness, however: Loeb believes that there might actually be a way out of this universal amnesia.

“The center of our galaxy keeps ejecting stars at high enough speeds that they can exit the galaxy,” Loeb says. The intense and dynamic gravity near the black hole ejects them into space, where they will glide away forever like radiating rocket ships. The same thing should happen a trillion years from now.

“These stars that leave the galaxy will be carried away by the same cosmic acceleration,” Loeb says. Future astronomers can monitor them as they depart. They will see stars leave, become alone in extragalactic space, and begin rushing faster and faster toward nothingness. It would look like magic. But if those future people dig into that strangeness, they will catch a glimpse of the true nature of the universe.

There might yet be hope for cosmological discovery, in the other words, encoded in the trajectories of these bizarre, fleeing stars.

[Images: (top) “An illustration of the Aristotelian/Ptolemaic cosmological system that was used in the Middle Ages, from the 1579 edition of Piccolomini’s De la Sfera del Mondo.” (bottom) “An illustration (influenced by Peurbach’s Theoricae Planetarum Novae) explaining the retrograde motion of an outer planet in the sky, from the 1647 Leiden edition of Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera.” Images and captions from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

[Images: (top) “An illustration of the Aristotelian/Ptolemaic cosmological system that was used in the Middle Ages, from the 1579 edition of Piccolomini’s De la Sfera del Mondo.” (bottom) “An illustration (influenced by Peurbach’s Theoricae Planetarum Novae) explaining the retrograde motion of an outer planet in the sky, from the 1647 Leiden edition of Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera.” Images and captions from Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography by Nick Kanas].

There are at least two reasons why I have been thinking about this today. One was the publication of an article by Dennis Overbye earlier this week about the rate of the universe’s expansion.

“There is a crisis brewing in the cosmos,” Overbye writes, “or perhaps in the community of cosmologists. The universe seems to be expanding too fast, some astronomers say.”

Indeed, the universe might be more “virulent and controversial” than currently believed, he explains, caught-up in the long process of simply tearing itself apart.

[Image: A “starburst galaxy” photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope].

[Image: A “starburst galaxy” photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope].

One implication of this finding, Overbye adds, “is that the most popular version of dark energy—known as the cosmological constant, invented by Einstein 100 years ago and then rejected as a blunder—might have to be replaced in the cosmological model by a more virulent and controversial form known as phantom energy, which could cause the universe to eventually expand so fast that even atoms would be torn apart in a Big Rip billions of years from now.”

In the process, perhaps the far-future dark ages envisioned by Krauss and Scherrer will thus arrive a billion or two years earlier than expected.

[Image: Engraving by Gustave Doré from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri].

[Image: Engraving by Gustave Doré from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri].

The second thing that made me think of this, however, was a short essay called “Dante in Orbit,” originally published in 1963, that a friend sent to me last night. It is about stars, constellations, and the possibility of determining astronomical time in The Divine Comedy.

In that paper, Frederick A. Stebbins writes that Dante “seems far removed from the space age; yet we find him concerned with problems of astronomy that had no practical importance until man went into orbit. He had occasion to deal with local time, elapsed time, and the International Date Line. His solutions appear to be correct.”

Stebbins goes on to describe “numerous astronomical references in [Dante’s] chief work, The Divine Comedy”—albeit doing so in a way that remains unconvincing. He suggests, for example, that Dante’s descriptions of constellations, sunrises, full moons, and more will allow an astute reader to measure exactly how much time was meant to have passed in his mythic story, and even that Dante himself had somehow been aware of differential, or relativistic, time differences between far-flung locations. (Recall, on the other hand, that Dante’s work has been discussed elsewhere for its possible insights into physics.)

[Image: Diagrams from “Dante in Orbit” (1963) by Frederick A. Stebbins].

[Image: Diagrams from “Dante in Orbit” (1963) by Frederick A. Stebbins].

But what’s interesting about this is not whether or not Stebbins was correct in his conclusions. What’s interesting is the very idea that a medieval cosmology might have been soft-wired, so to speak, into Dante’s poetic universe and that the stars and constellations he referred to would have had clear narrative significance for contemporary readers. It was part of their era’s shared understanding of how the world was structured.

Now, though, imagine some new Dante of a hundred billion years from now—some new Divine Comedy published in a trillion years—and how it might come to grips with the universal isolation and darkness of Krauss and Scherrer. What cycles of time might be perceived in the lonely, shining bulk of the Milky Way, a dying glow with no neighbor; what shared folklore about the growing darkness might be communicated to readers who don’t know, who cannot know, how incorrect their model of the cosmos truly is?

(Thanks to Wayne Chambliss for the Dante paper).

[Image: Test-crash from “

[Image: Test-crash from “ [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “FOGBAE.TWR4” by

[Image: “FOGBAE.TWR4” by  [Image: “reopot seven-ten” by

[Image: “reopot seven-ten” by  [Image: “pxil.two” by

[Image: “pxil.two” by  [Image: “OB TANK” by

[Image: “OB TANK” by  [Image: “FRIED GOBO” by

[Image: “FRIED GOBO” by  [Image: “MCD 2087” by

[Image: “MCD 2087” by  [Image: “orangetooth gutrot” by

[Image: “orangetooth gutrot” by  [Image: “BOXXX-3VV” by

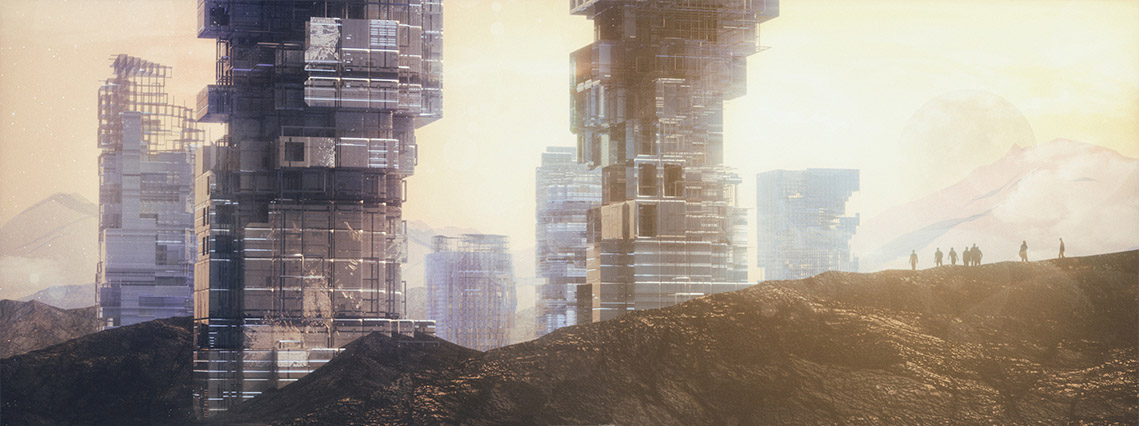

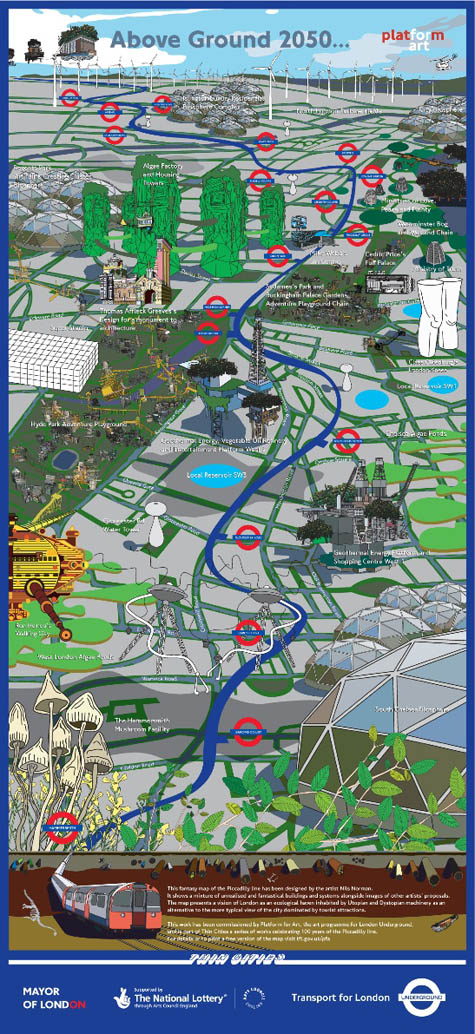

[Image: “BOXXX-3VV” by  [Image: “Above Ground” by

[Image: “Above Ground” by