[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists—co-sponsored by BLDGBLOG, Filmmaker Magazine, and Studio-X NYC—continued last week with Cool Hand Luke (1967), directed by Stuart Rosenberg.

The film tells the story of Luke Jackson, imprisoned for “maliciously destroying municipal property” by cutting the heads off parking meters. The very first word and image of the film is VIOLATION.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

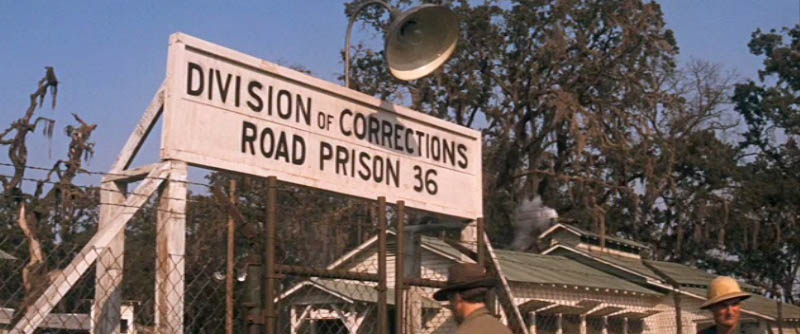

Luke is thus arrested and sent to a work camp in Florida, where he becomes, in effect, part of the country’s emerging national transportation infrastructure, paving rural roads through the Florida swamp.

He is immediately introduced to a new set of limitations. “We got all kinds,” the camp warden announces, referring to the prisoners kept behind fences there in the subtropical heat; but all of them have had to learn how to stay put. To this, the warden adds, “in case you get rabbit in your blood and you decide to take off for home,” you’ll be rewarded with more time in prison and a “set of leg chains to keep you slowed down just a little bit, for your own good. You’ll learn the rules.”

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Later, Luke meets the camp’s “floorwalker,” a man who keeps watch over the prisoners’ boarding house; the floorwalker unloads an absurd and seemingly endless monologue about how the prisoners can avoid spending “a night in the box,” a small building the size of an outhouse with no pretenses of comfort or hygiene. The list of steps by which to avoid this fate—involving everything from laundry to yard tools—is mind-numbing and absolutely impossible to remember.

When the rest of the camp comes back inside to shower and meet these newly arrived state captives, tension between Luke and the existing group’s ostensible leader, nicknamed Dragline, is established immediately. “You don’t listen much—do you, boy?” Dragline growls, mistaking his own corpulence for an ability to intimidate. Luke barely looks at him in return. “I ain’t heard that much worth listening to,” he mutters. “Just a lot of guys laying down a lot of rules and regulations.”

[Image: The camp; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: The camp; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

As such, the film offers an interesting mix of, on the one hand, the surreal impossibility of reasoning with the state and its hired representatives (similar, say, to the writings of Franz Kafka); and, on the other, what seems to be a particularly American breed of libertarianism, one in which even parking meters can be interpreted as “just a lot of guys laying down a lot of rules and regulations,” where all instances of authority are meant to be, if not resisted, than at least publicly mocked and undercut.

[Images: Lucas Jackson meets the blinding lights of the state; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: Lucas Jackson meets the blinding lights of the state; from Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

As we’ll see—and this post contains spoilers, for those of you who haven’t seen the film yet—Cool Hand Luke becomes a kind of Trial-like cautionary tale, suggesting that the end result of playfully antagonizing the state can often be repression or death.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

So Luke, a nonviolent offender, is sent off to pave roads in the heat, clearing weeds and snakes, and otherwise maintaining national infrastructure alongside others in his imprisoned crew. They are, in a sense, tragically ensnared in the geographic project of the state, which seeks to expand ceaselessly into underserved rural areas by means of convict-facilitated construction projects. And thus the nation—brutally, physically, literally—is made.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

This relentless growth of the well-policed roadway is perhaps the film’s central motif—even above the film’s admittedly more entertaining scenes, such as Luke living up to his own challenge of eating 50 hard-boiled eggs. For instance, in one scene where a particularly manic Luke successfully challenges the rest of his crew to treat the day’s road-paving assignment like a race, they’re left confused and dumbfounded when the tar truck drives away. The inmates are left staring at a STOP sign. “Where’d the road go?” an exasperated Dragline asks, as if they’re now faced with doing nothing.

But that’s precisely it: the only thing left to do is nothing. This recalls how Luke gets his nickname—”Cool Hand Luke”—by bluffing his way to victory in a poker game, holding a hand “full of nothing.”

In any case, Luke responds by laughing at the idiocy of the entire situation. They ran a race against nothing and no one won.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

For those of you who have seen the film, there is clearly much more in it to discuss that is not spatial or architectural, and I would hope that such a conversation could still take place, either here in the comments or someday with friends; but, given the thematic emphasis of the Breaking Out and Breaking In film series, I’ll focus on just a few more things.

Luke, of course, escapes—three times—but not once, in any long term sense, is he successful, getting hauled back to camp twice in chains.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Luke’s various punishments for these attempted escapes grow in severity, suggesting a dark answer to the question proposed by a commenter on an earlier BLDGBLOG post: “How do you design a space to break someone’s spirit? A horrible and unimaginable commission.”

Specifically, Luke first spends “a night in the box” and is then forced—inverting all of the power implications associated with digging, tunneling, and moving dirt that we’ve seen so far in the Breaking Out series—to dig and refill a hole in the prison yard, several times over, effectively breaking his will. At one point he is even pushed back into the hole, as if he has, all along, been digging his own grave.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

After witnessing Luke’s very audible collapse, his fellow inmates refuse to speak with him after he stumbles back to the bunkhouse, as if Luke’s aura of indefatigability has been permanently smudged by this performance of desperate weakness. The “horrible and unimaginable commission” of breaking his spirit has, it seems, been accomplished.

However, Luke has one more escape in him, driving off unexpectedly in a road-servicing truck and disappearing into the parched landscape seen reflected in the mirrored sunglasses of the silent “boss” (and sharpshooter) who watches over him.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

This, then, will be my final point about the film: in what is otherwise an obvious—even hackneyed—scene, played for all its poetic and metaphoric power, Luke finds himself alone in an empty church at night, unsure of where to run to next. In many ways, this is where the film’s Kafka-esque themes are most clearly foregrounded, as Luke, addressing God for the second time in the film, finds himself simply speaking to empty rafters.

The church is silent, just a bunch of a wood and darkness, and Luke realizes, once and for all, that no one will be answering.

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Again, this is far from dramatically original, but the scene strongly benefits from its proximity to Luke’s earlier solicitations of authority. In other words, Luke rattles the doors of the divine only to find no response—he finds an empty room and silence. But, when he rattles the doors of the state, an altogether different and more mundane body of authority, it responds by crashing down upon him, relentlessly and absolutely, ultimately leading to his death by sharpshooter (inside the door of a church, no less).

What began as a nonviolent prank, cutting the heads off parking meters, ends, in effect, with a death sentence, as Luke’s ongoing antagonism of the state is seen not as a playful engagement with arbitrary authority, but as an offense so grave—a bluff with an empty hand, holding nothing—that Luke’s very existence is, we might say, reneged or cancelled out. And when he calls up to God, he hears nothing.

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Briefly, I’m reminded of the extraordinary film The Story of Qiu Ju, in which a Chinese villager calls upon the machinations of the state in order to solve a matter of local justice, only to find, to her growing dismay, that she has set into motion something incoherent, lumbering, deaf, and unstoppable.

Only, here, Luke is at the receiving end of something Qiu Ju only witnesses—as if he has snapped the trip-wire of the state, becoming lethally ensnared in a system from which escapes are punishable by death, no matter how trivial the initial offense might be.

[Image: Luke’s apotheosis, ascending above the cross of the roadway; Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: Luke’s apotheosis, ascending above the cross of the roadway; Cool Hand Luke, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

In any case, Cool Hand Luke is, in the end, a strangely affecting film, seemingly more tragic each time I see it; but I’m sure there’s much more to discuss, so feel free to jump in with any thoughts or comments.

(Up next: Breaking Out and Breaking In continues with Cube. Complete schedule available here).

What…are you kidding me? This is a story of a Jesus figure. That's all. He's a leader but he leads without brutality. He leads with a smile and an inner strength.

Notice in the egg scene…besides that it's really funny, he eats 50 eggs – there are fifty prisoners. He's saving, protecting them from persecution. Notice the color white and where it appears. Notice the scene where the other prisoners come and eat the rice from his plate – it's The Last Supper!

This movie is a Christ parable with a cooler lead.

This has nothing to do with bucking the system. And as much as I'm not a fan of the concept, in the final scene, as Luke (Christ figure) is questioning God's/his place in the universe and he's summarily shot. Is that the director's final statement upon God? Well, that's your call.

But, please…it has nothing to do with 60's revolt against "the man". It's a retelling of a biblical story.

I disagree w this premise, much more man vs state film

Thanks, JBH; what a productive way to open up new discussions of the film.

My spatially-related mental note while watching the film came during the escape scene. Fascinating how Luke had to understand the space of his escape not only in terms of (1) where he's running away from; (2) where he might be running to; and perhaps most interestingly (3) from the perspective of those who will pursue him.

To evade the dogs, he obviously considers how the dogs will track him (by scent) and how they move through space (tethered to the guards). He tries to circumvent leaving a trail by running through water and leaving the ground whenever possible. He frustrates the dogs and the guards they are tied to by hoping back and forth over a fence – delaying the pursuit by forcing the dogs to weave in and around through the fence entangling themselves with the guards.

Of course the issue of solitary confinement carries into this film. But I think I will hold further comments until Papillon.

I love this movie and have seen it many times, but the significance of the road has never struck me before.

The road was then promising America "freedom," but here it's built on the backs of literal slave labor and prisoners. Luke, meanwhile, deliberately plants himself "inside" (ironically enough by "freeing" the parking spaces), perhaps to prove to himself that the human spirit can be free regardless of walls or ownership.

The religious overlay is unmistakable, but Luke is ultimately all too human. It is perhaps in this that the movie is its most radical.

Thanks for getting me thinking. I will have to watch this again with more consciousness of the spatial issues.

Will, thanks for the comment; I like the irony you mention about the (highly stationary) parking spaces and their liberation resulting in Luke's own immobilization.

Sarah, thanks for this and your earlier comment, as well. I love the notion—and wish I had been the one to notice!—Luke's "leaving the ground whenever possible" in his escape attempts. I look forward to your comments on Papillon!

We're in a moment when such a film can't be made, except as a parody of itself. Viz: 'Harold and Kumar go to Guantanamo.'

The Christ parallels are obvious, but sorry JBH… Christ was playing the same kind of game with authority that Luke is.

Also, this film is the essence of Americanism, especially American masculinity. It's a film that surely always existed in the American aether and was simply made manifest at just the right time.

Americans love to see themselves as Cool Hand Luke, playfully pushing the boundaries of acceptability. Americans also love to see themselves as the corpulent authority figure, able to bully others into compliance.

We choose not to see ourselves as the other prisoners or minor guards, despite the sad fact that we really do occupy those roles. We want to be the badass, but we never step up quite enough to follow through. And we don't, because we know we'd become either the dead Luke or the monsters that killed him.

Anon – the masculinity of the movies is something I've been thinking about. It's pretty dominant in the genre. Obviously lots that could be discussed. Anyone have thoughts specifically on the spatial implications?

Great point about the Americanism. Freedom seems to be tied to ownership/control/dominance over land and claiming control from the oppressors.

Also interesting to consider the individual hero's quest for freedom in contrast to the group effort of the Great Escape. For Luke it's a personal pursuit. For the prisoners in the Great Escape it is duty to their country. Though this may just be a reflection of the very different reasons for their imprisonment in the two cases – personal crime vs. POW.

I'm not convinced about Luke's "masculinity." He is certainly stuck in an incredibly "masculine" environment, but he himself is awfully "sensitive" to be a typical macho stereotype (this was 50 years ago…we need to read it in that light). The most poignant moment of the whole movie is him nearly crying over his mother, and it's pointed that he sings the "plastic Jesus" song — a song about a statue on a dashboard — free on the road — when he is denied the chance to move. And when he "wins" the fistfight, it's not through superior strength, but from being willing to suffer more. It's akin to non-violent resistance. "Stay down," I recall the big guy (George Kennedy?) telling him–keep your proper place–your low spot. He is shamed into stopping.

Anyway, I think authority is represented here as male because that's the world he lives in. (And it's still the world most of us live in, for all intents and purposes.)

I do think you're right on about the prison being a microcosmos of America. I think the movie is also bigger than that, but that's definitely its setting. America is far more stratified and class-based than anyone likes to think.

Anonymous, I would take issue, briefly, with your notion that U.S. audiences uniquely "choose not to see ourselves as the other prisoners or minor guards" when watching a film such as this, implying that viewers in other countries might see Cool Hand Luke and, bucking dramatic conventions, decide to identify with an undeveloped character in the background who only gets one line.

In other words, I think audience identification with either the protagonist or the antagonist is simply part of a film's (or a novel's) dramatic structure; and I suppose, following your point, the real question would be about why U.S. films so consistently feature a recognizable hero and a recognizable villain, surrounded by minor characters, as opposed to the kind of ensemble casts with no lead actor that are much more common in, say, British film and television today.

My point is simply that I don't think U.S. viewers are alone in, or should be pathologized for, watching a movie such as Cool Hand Luke and identifying—or at least paying more attention to—the film's dramatic lead. In a sense, that's what the film is made for. The question, in a way, would be: what sort of movie would result if Cool Hand Luke could be remade without a main character, instead following a fully developed ensemble cast around the prison yard? Then you could ask which character U.S. viewers most consistently seem to identify with; and from that information you could perhaps begin to generalize about the 300 million people or so, of very diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds, who make up the "Americans" to whom you refer in your comment.

This movie has one of the greatest scenes about digging and one of the best lines to use when you start someone excavating for a project, 'This here's your dirt, what's your dirt doing in my ditch.' Nothing quite like a reference to prison labor to get a crew in the right mind for some construction.

Thanks for the post and the comments (got here via Metafilter). One of the joys of parenthood is turning your kids on to great movies, and I just screened this with my 14-yr old a few weeks ago. It's a testament to the film that it can appeal to viewers of different ages and eras so well, on many different levels. I had been aware of the religious themes that run throughout the movie, and I–like at least one other commenter–view Luke as an all-too-human Jesus figure, of the mold which was popular in the 60's; i.e., anti-authoritarian to the core. I don't think the film asserts an atheist or a theist position, but intentionally leaves open the question as to whether Luke is really 'just talkin' to himself' This makes the film a good example of existential philosophy, wherein the free will of man must ultimately face the harsh realities of existence.

I would disagree with this comment: "In other words, Luke rattles the doors of the divine only to find no response—he finds an empty room and silence."

I'd say that the silence IS God's response. Luke shoots back with something along the lines of "Have it your way Old Man." In fact don't his pursuers show up right after he asks God for a response?

Anon: I definitely see the movie as coming from a theist perspective, because there is so much Luke-as-Jesus imagery.

I am definitely going to watch that now, thank you! 🙂

In all this discussion of the Christ parallel no has mentioned the very overt crucifixion imagery when Luke lays on the table after eating the 50 eggs. Pretty blatant:

http://sheepnoir.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/large-cool-hand-luke-blu-ray73.jpg

There's no question the parallel with Jesus is there, though it's also just as obvious it's not "…has nothing to do with 60's revolt against "the man". It's a retelling of a biblical story."

Please. Luke isn't Jesus. He's not preaching. He's not sure of anything he's doing. He's a lost soul simply trying to survive. If anything it's a fatalistic treatise of existentialism as told through the malaise of PTSD (Luke is a decorated solider).

The movie's Jesus nods are done for dramatic commentary, not to insinuate that they're the same person.

Stop trying to rope the ‘devine’ into the theme of this film. If anything God dealt Luke a bad hand in life. Nothing to be thankfull for. But a hand Luke learns how to play with consummate skill. The lowest point for Luke is when his mother dies and he has to spend several days in ‘the box’. Simply because the captain thinks it’s best for him. I believe it’s at that point in the film that Luke decides he’s had enough of camp life and he’s going to bust out at

all cost. All the while under the watchfull eye of the man in

sunglasses,,,who seems to be paying special attention to Luke.

He has no dialogue in the film at all. Just this stone cold stare, thru a pair of mirror sunglasses,that could freeze hell over in a minute. And a guy who

could shoot a fly at 100 feet with his bolt action rifle. Oddly, at the

end of the film, Dragline tackles him and beats the crap out of him when he shoots and kills Luke.

And we catch a brief glimpse of a weakened and more vulnerable ruthless boss man. It is worth noting the debut of several budding actors in this film who later became stars in their own.

Dennis Hopper, Ralph Waite, Harry Dean Stanton, and that guy who played original Haweye in MASH (sorry, his name eludes me) among others. George Kennedy was already a well known at the time IMO.

‘Go get the bolt gun Luke.’ Did the an with no eyes say this? I sort of remember him pulling the rifle’s bolt from his belt.

Man with no eyes, the road boss with the mirror RayBans.

My elder brothers called my dad “Luke” for as long as I could remember when growing up…I was born in 1960. It was not until I was in my teens that I saw the movie and then realized where they got the nickname….not for the main character but the man with no eyes, my father had achieved the marksman medal/badge in WWII and none of us ever saw him miss a target when hunting on our farms we grew up on…