Despite taking a strong public stance against modern climate science, oil firms such as Mobil and Shell have calculated the effects of climate change-induced sea-level rise into the construction of their drilling platforms and coastal facilities, the Los Angeles Times reports.

Tag: Architecture

Bonus Levels

Over at AVANT, Lawrence Lek explores the spatial metaphor of “bonus levels,” or what he calls “the continuation of architecture through other means: an ongoing series of fictitious, utopian landscapes conceived as site-specific simulations.”

Whale Song Bunker

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the BBC].

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the BBC].

This is the most awesomely surreal architectural proposal of 2015: an extremely remote Cold War-era submarine surveillance station on the Isle of Lewis in the Scottish Outer Hebrides might soon be transformed into a kind of benthic concert hall for listening to whale song.

“A community buy-out could see a former Cold War surveillance station turned into a place where tourists can listen to the sound of whales singing,” the BBC reports.

During the Cold War, we read, “the site was part of NATO’s early warning system against Soviet submarines and aircraft, but the Ministry of Defence has no further use for the derelict buildings on the clifftop site.”

“It is now hoped a hydrophone could be placed in the sea to pick up the sound of whales.”

The idea of “derelict buildings on [a] clifftop site” resonating with the artificially amplified sounds of distant whales is amazing, like some fantasy acoustic variation on the “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm.

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm].

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm].

I couldn’t find any further word on whether or not this plan is actually moving forward, but, if not, we should totally Kickstart this thing—and, if not there, then perhaps reusing the old abandoned bunkers of the Marin Headlands.

Your own private whale song bunker, reverberating with the inhuman chorus of the deep sea.

(Story originally spotted via Subterranea, the journal of Subterranea Britannica).

Howl

I watched this video with the typical ennui of your average internet user—expecting to hear nothing at all, really, before going back to other forms of online procrastination—but holy Hannah. This is a pretty loud building.

Although I would be making surreptitious ambient field recordings—and rhapsodizing to my sleepless friends about the unrealized acoustic dimensions of contemporary architecture—I have to say I’d be pretty unenthused to have this thing howling all day, everyday, in my neighborhood.

It’s Manchester’s Beetham Tower. It cost £150 million to build, and its accidental sounds are apparently now “the stuff of legend.”

(Spotted via Justin Davidson. This actually reminds me of when my housemate in college taught himself to play the saw and I had no idea what was happening).

When those who it was built for are not present

[Image: Photo by Kai Caemmerer].

[Image: Photo by Kai Caemmerer].

I’ve got a new article up over at New Scientist looking at the so-called “ghost cities” of China, and where exactly they can be found. This is not as straightforward as it might seem:

It seems hard to lose track of an entire city. But that appears to be what’s taken place—and not just once, but over and over again. The infamous “ghost cities” of China have become a favorite internet meme of the past half-decade. These ghost cities are meant to be sprawling wastelands of empty streets and uninhabited megastructures, without a human being in sight. But for all the discussion, do these places really exist?

The rest of the piece looks at various strategies put to use not only for quantifying but for simply locating these developments in the first place. This includes data analysis and satellite photography—but, just as compellingly, on-the-ground firsthand exploration.

[Image: Photo by Kai Caemmerer].

[Image: Photo by Kai Caemmerer].

Here, I talked to photographer Kai Caemmerer who has recently undertaken a series of photos exploring what he calls “unborn cities,” or cities not dead and expired—that is, not ghost cities—but cities that are incomplete and still awaiting their future populations.

“Unlike many Western cities that begin as small developments and grow in accordance with local industries, gathering community and history as they age,” Caemmerer explains, “these areas are built to the point of near completion before introducing people.”

Because of this, there is an interim period between the final phases of development and when the areas become noticeably populated, when many of the buildings stand empty, occasionally still cloaked in scrim. During this phase of development, sensationalist Western media often describe them as defunct “ghost cities,” which fails to recognize that they are built on an urban model, timeline, and scale that is simply unfamiliar to the methods of Western urbanization.

Caemmerer continued, pointing out that his interest in ostensibly empty urban environments is not about shaming China, or implying that unused architectural space is somehow only a non-Western problem. In fact, in another series—a few example of which I hope to post here in the near-future—Caemmerer turns his lens on his own home city of Chicago.

“I’m interested in what happens to the urban landscape when those who it was built for are not present,” he explained to me. “More specifically, I’m interested in what can be revealed by the architecture when it appears vacant. ”

Read more over at New Scientist.

(Thanks to Richard Mosse for putting me in touch with Caemmerer).

A Model Descent

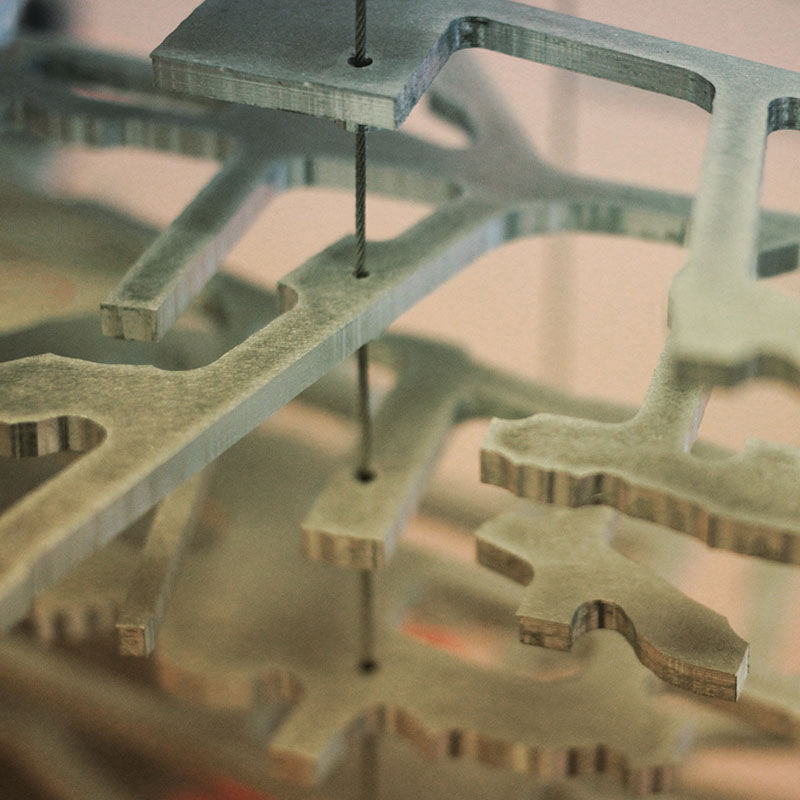

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota, was once “the largest, deepest and most productive gold mine in North America,” featuring nearly 370 miles’ worth of tunnels.

Although active mining operations ceased there more than a decade ago, the vast subterranean labyrinth not only remains intact, it has also found a second life as host for a number of underground physics experiments.

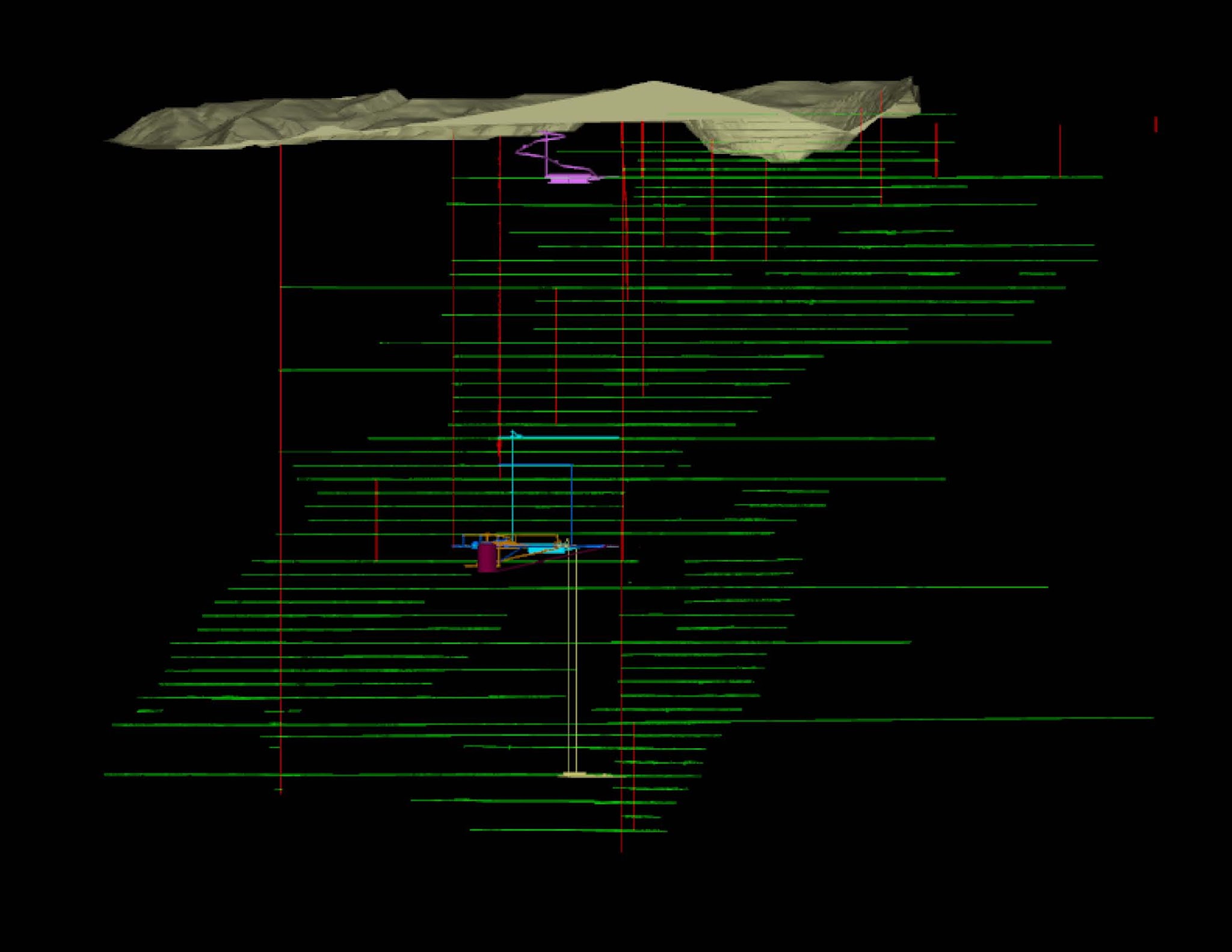

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

These include a lab known as the Sanford Underground Research Facility, as well as a related project, the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory (or DUSEL).

Had DUSEL not recently run into some potentially fatal funding problems, it “would have been the deepest underground science facility in the world.” For now, it is on hold.

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Digital model of the old mine tunnels beneath Lead, South Dakota; via SITU Fabrication].

There is already much to read about the experiments going on there, but one of the key projects underway is a search for dark matter. As Popular Science explained back in 2010:

Now a team of physicists and former miners has converted Homestake’s shipping warehouse into a new surface-level laboratory at the Sanford Underground Laboratory. They’ve painted the walls and baseboards white and added yellow floor lines to steer visitors around giant nitrogen tanks, locker-size computers and plastic-shrouded machine parts. Soon they will gather many of these components into the lab’s clean room and combine them into LUX, the Large Underground Xenon dark-matter detector, which they will then lower halfway down the mine, where—if all goes well—it will eventually detect the presence of a few particles of dark matter, the as-yet-undetected invisible substance that may well be what holds the universe together.

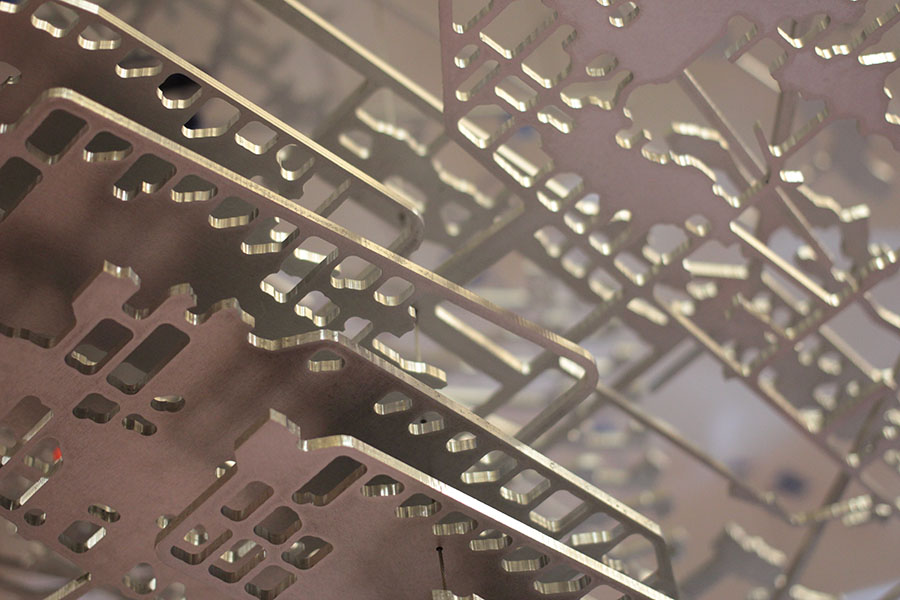

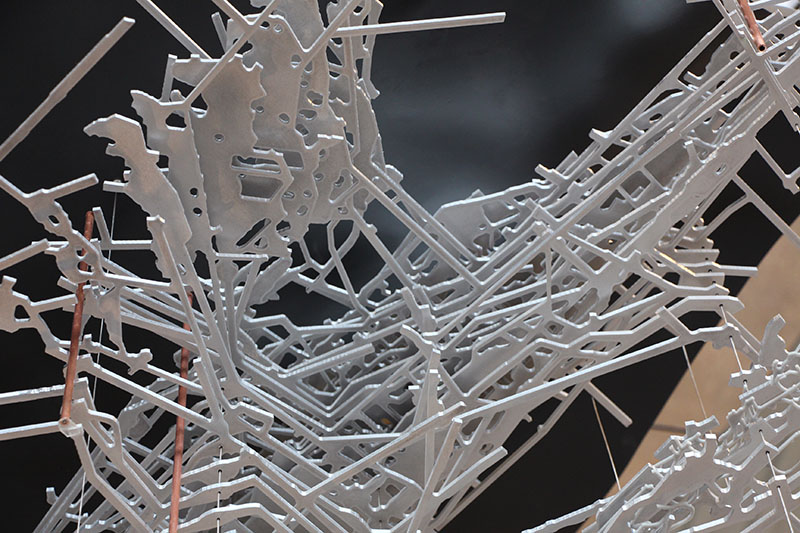

Earlier this year, I was scrolling through my Instagram feed when I noticed some cool photos popping up from a Brooklyn-based firm called SITU Fabrication. The images showed what appeared to be a maze of strangely angled metal parts and wires, hanging from one another in space.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by SITU Fabrication].

One of them—seen above, and resembling some sort of exploded psychogeographic map of Dante’s Inferno—was simply captioned, “#CNC milled aluminum plates for model of underground tunnel network in #SouthDakota.”

Living within walking distance of the company’s DUMBO fabrication facility, I quickly got in touch and, a few days later, stopped by to learn more.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

SITU’s Wes Rozen met me for a tour of the workshop and a firsthand introduction to the Homestake project.

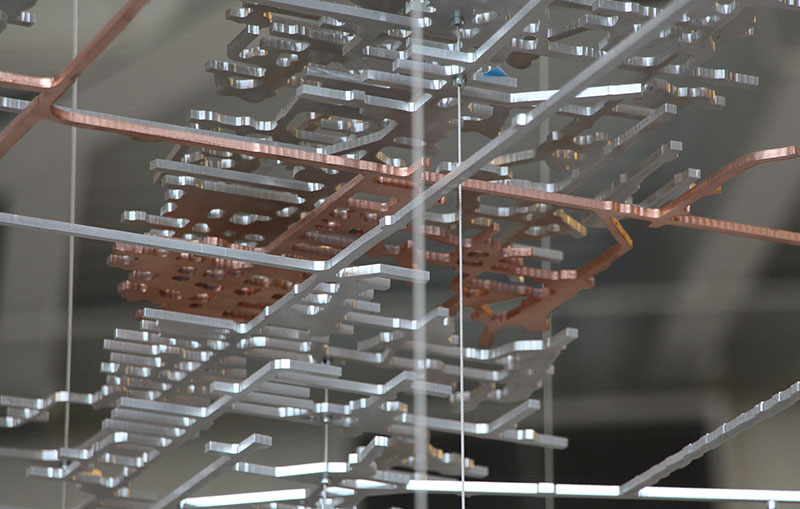

The firm, he explained, already widely known for its work on complex fabrication jobs for architects and artists alike, had recently been hired to produce a 3D model of the complete Homestake tunnel network, a model that would later be installed in a visitors’ center for the mine itself.

Visitors would thus encounter this microcosm of the old mine, in lieu of physically entering the deep tunnels beneath their feet.

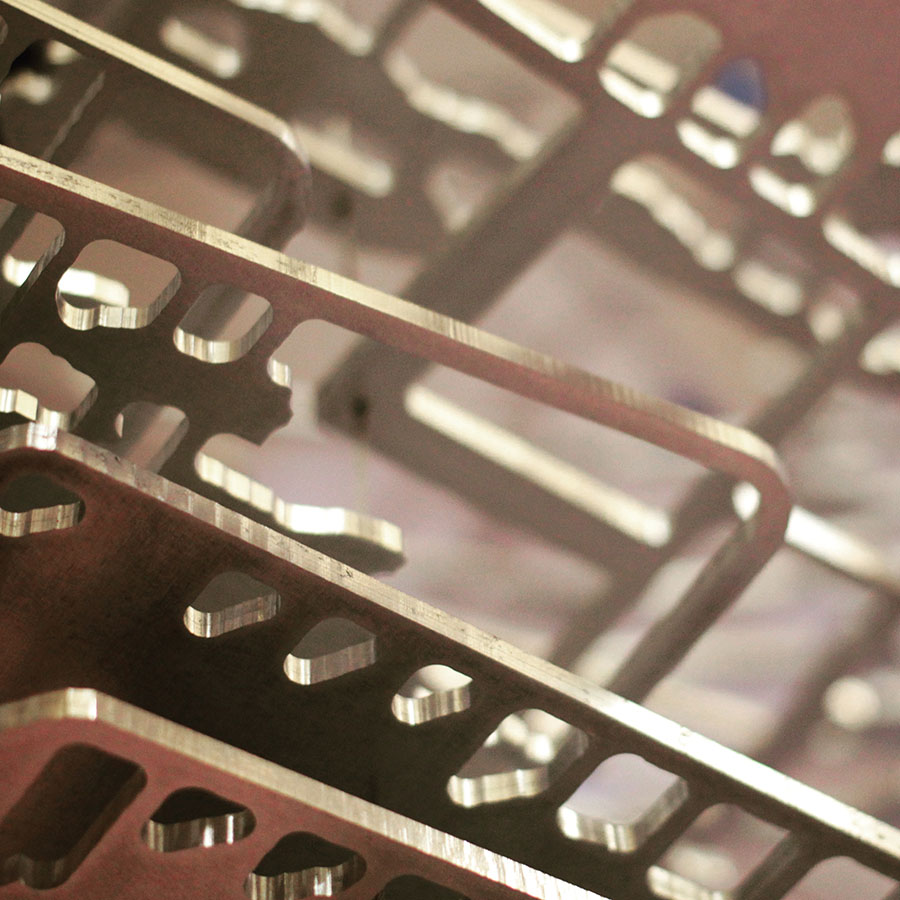

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

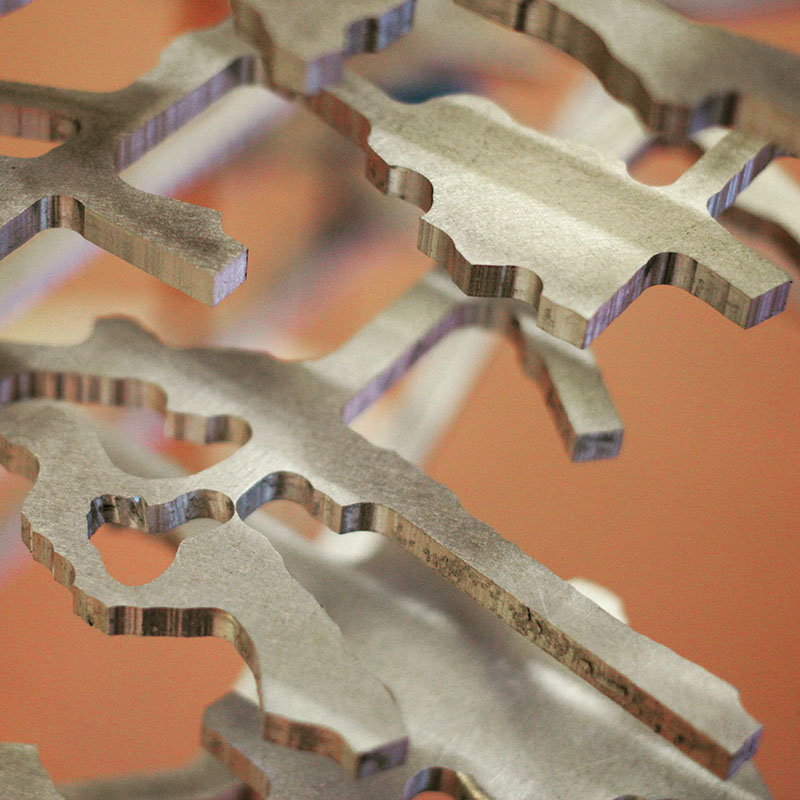

Individual levels of the mine, Rozen pointed out, had been milled from aluminum sheets to a high degree of accuracy; even small side-bays and dead ends were included in the metalwork.

Negative space became positive, and the effect was like looking through lace.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

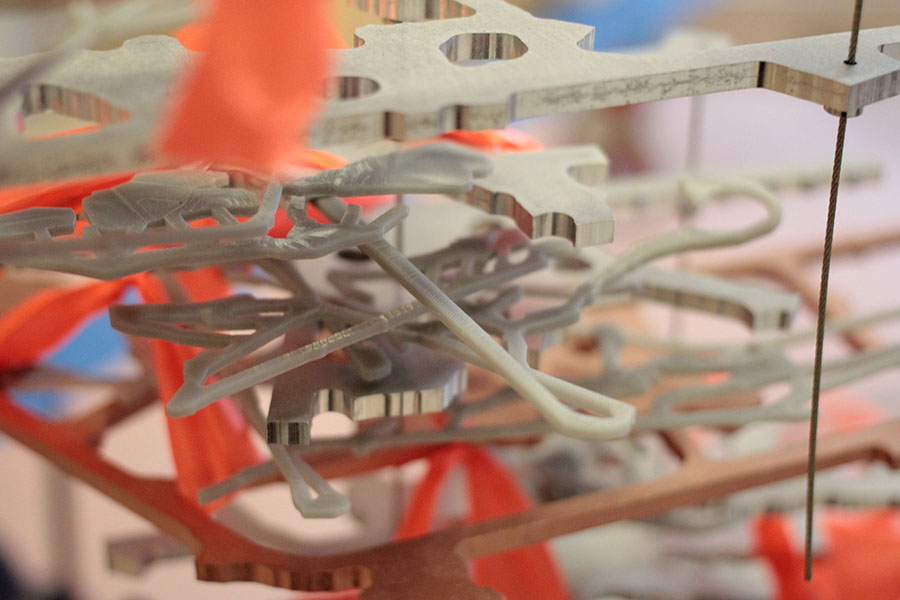

Further, tiny 3D-printed parts—visible in some photographs, further below—had also been made to connect each level to the next, forming arabesques and curlicues that spiraled out and back again, representing truck ramps.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; Instagram by BLDGBLOG].

The whole thing was then suspended on wires, hanging like a chandelier from the underworld, to form a cloud or curtain of subtly reflective metal.

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

When I showed up that day, the pieces were still being assembled; small knots of orange ribbon and pieces of blue painter’s tape marked spots that required further polish or balancing, and metal clamps held many of the wires in place.

[Images: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos by BLDGBLOG].

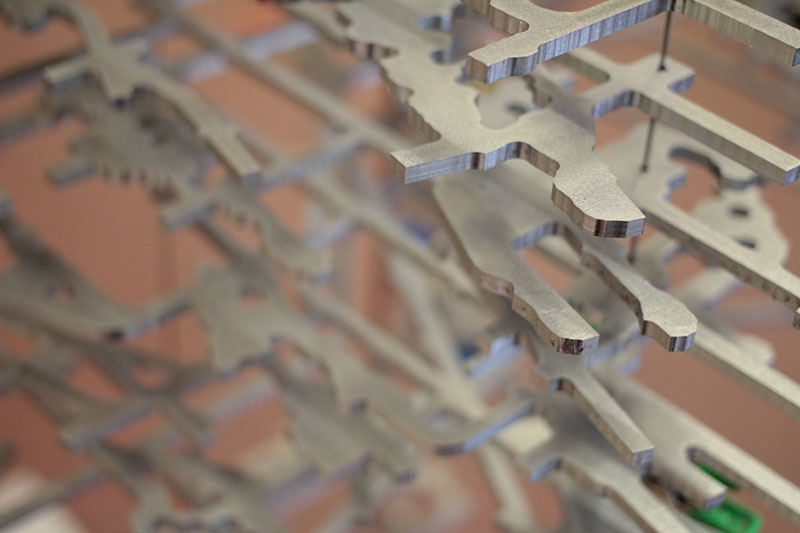

Seen in person, the piece is astonishingly complex, as well as physically imposing—in photographs, unfortunately, this can be difficult to capture.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

However, the sheer density of the metalwork and the often impossibly minute differences from one level of the mine to the next—not to mention, at the other extreme, the sudden outward spikes of one-off, exploratory mine shafts, shooting away from the model like blades—can still be seen here, especially in photos supplied by SITU themselves.

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembly of the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

A few of the photos look more like humans tinkering in the undercarriage of some insectile aluminum engine, a machine from a David Cronenberg movie.

[Image: Assembling the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: Assembling the model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Which seems fitting, I suppose, as the other appropriate analogy to make here would be to the metal skeleton of a previously unknown creature, pinned up and put together again by the staff of an unnatural history museum.

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo by BLDGBLOG].

The model is now complete and no longer in Brooklyn: it is instead on display at the Homestake visitors’ center in South Dakota, where it greets the general public from its perch above a mirror. As above, so below.

[Images: The model seen in situ, by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Images: The model seen in situ, by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photos courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Again, it’s funny how hard the piece can be to photograph in full, and how quick it is to blend into its background.

This is a shame, as the intricacies of the model are both stunning and worth one’s patient attention; perhaps it would be better served hanging against a solid white background, or even just more strategically lit.

[Image: The model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

[Image: The model by SITU Studio with C&G Partners; photo courtesy of SITU Fabrication].

Or, as the case may be, perhaps it’s just worth going out of your way to see the model in person.

Indeed, following the milled aluminum of one level, then down the ramps to the next, heading further out along the honeycomb of secondary shafts and galleries, and down again to the next level, and so on, ad infinitum, was an awesome and semi-hypnotic way to engage with the piece when I was able to see it up close in SITU’s Brooklyn facility.

I imagine that seeing it in its complete state in South Dakota would be no less stimulating.

(Vaguely related: Mine Machine).

Extract

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

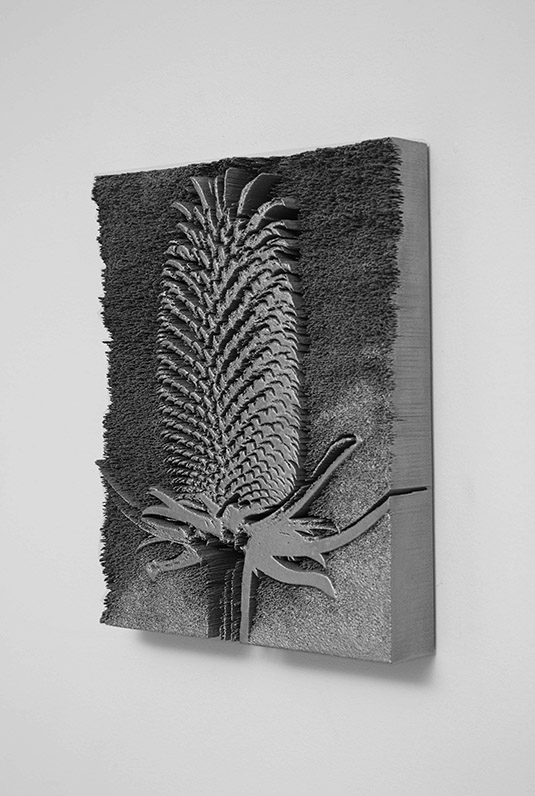

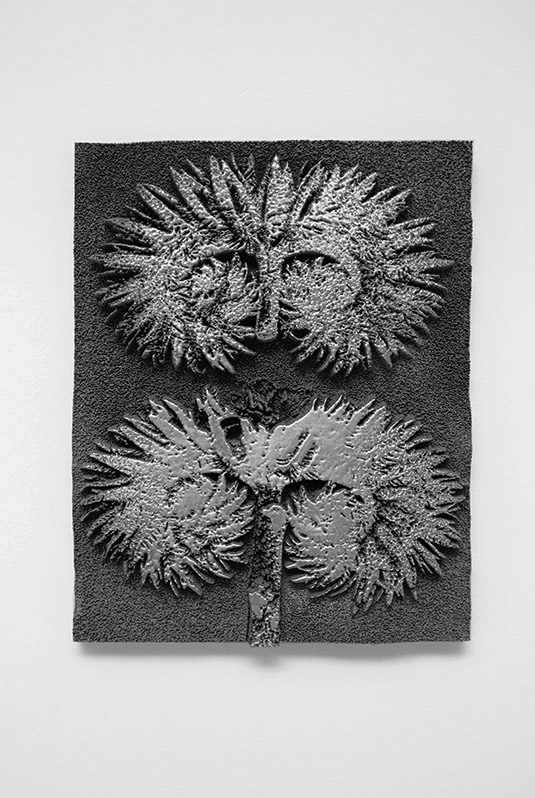

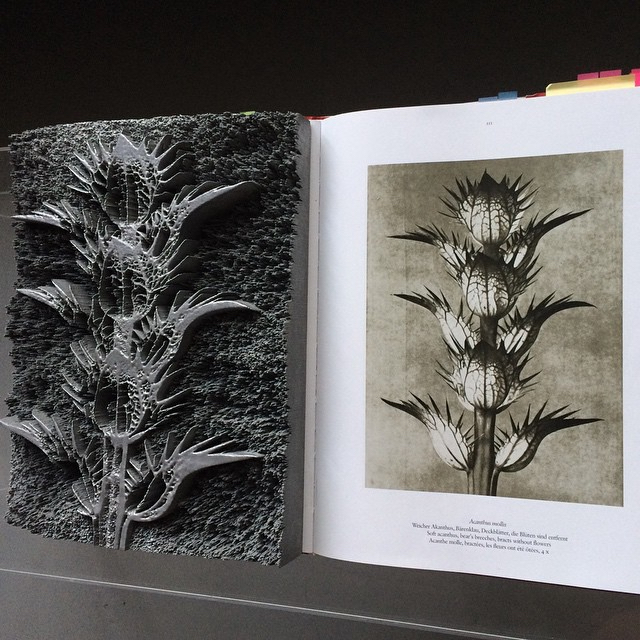

Artist Spiros Hadjidjanos has been using an interesting technique in his recent work, where he scans old photographs, turns their color or shading intensity into depth information, and then 3D-prints objects extracted from this. The effect is like pulling objects out of wormholes.

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

His experiments appear to have begun with a project focused specifically on Karl Blossfeldt’s classic book Urformen der Kunst; there, Blossfeldt published beautifully realized botanical photographs that fell somewhere between scientific taxonomy and human portraiture.

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Stylemag].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Stylemag].

As Hi-Fructose explained earlier this summer, Hadjidjanos’s approach was to scan Blossfeldt’s images, then, “using complex information algorithms to add depth, [they] were printed as objects composed of hundreds of sharp needle-like aluminum-nylon points. Despite their space-age methods, the plants appear fossilized. Each node and vein is perfectly preserved for posterity.”

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

The results are pretty awesome—but I was especially drawn to this when I saw, on Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed, that he had started to apply this to architectural motifs.

2D architectural images—scanned and translated into operable depth information—can then be realized as blurred and imperfect 3D objects, spectral secondary reproductions that are almost like digitally compressed, 3D versions of the original photograph.

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

It’s a deliberately lo-fi, representationally imperfect way of bringing architectural fragments back to life, as if unpeeling partial buildings from the crumbling pages of a library, a digital wizardry of extracting space from surface.

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

There are many, many interesting things to discuss here—including three-dimensional data loss, object translations, and emerging aesthetics unique to scanning technology—but what particularly stands out to me is the implication that this is, in effect, photography pursued by other means.

In other words, through a combination of digital scanning and 3D-printing, these strange metallized nylon hybrids, depicting plinths, entablatures, finials, and other spatial details, are just a kind of depth photography, object-photographs that, when hung on a wall, become functionally indistinct from architecture.

Shell

[Image: “Vaulted Chamber” by Matthew Simmonds].

[Image: “Vaulted Chamber” by Matthew Simmonds].

While writing the previous post, I remembered the work of Matthew Simmonds, a British stonemason turned sculptor who carves beautifully finished, miniature architectural scenes into otherwise rough chunks of rock.

[Image: “Sinan: Study” by Matthew Simmonds].

[Image: “Sinan: Study” by Matthew Simmonds].

Simmonds seems primarily to use sandstone, marble, and limestone in his work, and focuses on producing architectural forms either reminiscent of the ancient world or of a broadly “sacred” character, including temples, church naves, and basilicas.

[Image: “Basilica III” by Matthew Simmonds].

[Image: “Basilica III” by Matthew Simmonds].

You can see many more photos on his own website or over at Yatzer, where you, too, might very well have seen these last year.

[Image: “Fragment IV” by Matthew Simmonds].

[Image: “Fragment IV” by Matthew Simmonds].

Someone should commission Simmonds someday soon to carve, in effect, a reverse architectural Mt. Rushmore: an entire hard rock mountain somewhere sculpted over decades into a warren of semi-exposed rooms, cracked open like a skylight looking down into a deeper world, where Simmonds’s skills can be revealed at a truly inhabitable spatial scale.

(Previously: Emerge).

Emerge

[Image: Originally an ad for the Cité de l’Architecture in Paris].

[Image: Originally an ad for the Cité de l’Architecture in Paris].

I originally spotted this image a while back via the Tumblr Architectural Models, but it appears actually to have been created as part of an ad campaign for the Cité de l’Architecture in Paris.

Whatever its actual provenance might be, I love the idea of leaving in place the partially excavated backdrop out of which an architectural model emerges, the rough material matrix—be it wood, rock, or 3D-misprinted plastic—whose precise spatial shaping becomes all the more clear when you can compare a form with its formless origins.

Ghosting

[Image: From Pierre Huyghe, “Les grandes ensembles” (2001)].

[Image: From Pierre Huyghe, “Les grandes ensembles” (2001)].

A short news items in New Scientist this week describes the work of University of Michigan engineers who have developed a way to, in effect, synchronize architectural structures at a distance. They refer to this as “ghosting”:

When someone turns the lights on in one kitchen, they automatically switch on in the connected house. Sounds are picked up and relayed, too. Engineers at the University of Michigan successfully linked an apartment in Michigan with one in Maryland. The work was presented at the IoT-App conference in Seoul, South Korea, last week.

I haven’t found any more details about the project—including why, exactly, one would want to do this, other than perhaps to create some strange new electrical variation on “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” where a secret reference-apartment is kept burning away somewhere in the American night—but no doubt more info will come to light soon.*

*Update: Such as right now: here is the original paper. There, we read the following:

Ghosting synchronizes audio and lighting between two homes on a room-by-room basis. Microphones in each room transmit audio to the corresponding room in the other home, unifying the ambient sound domains of the two homes. For example, a user cooking in their kitchen transmits sounds out of speakers in the other user’s own kitchen. The lighting context in corresponding rooms is also synchronized. A light toggled in one house toggles the lights in the other house in real time. We claim that this system allows for casual interactions that feel natural and intimate because they share context and require less social effort than a teleconference or phone call.

Thanks to Nick Arvin, both for finding the paper and for highlighting that particular quotation.

Shelter

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

These gorgeous timber pods are a series of “asymmetric nature shelters” designed by LUMO Architects for the Danish South Fyn islands.

According to a write-up over on designboom, they function a bit like traditional Japanese moon-viewing platforms: “clad with large wood chips treated with black-pigmented wood tar oil,” we read, “the randomly displaced openings look out and frame the surrounding nature and at night, the lunar orbit across the night sky can be observed.”

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

It will be interesting to see how they weather and fade over time, of course—and, in the bottommost images seen here, you can already see them transitioning to grey—but, for now, these look spectacular.

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

The black exterior shell creates a particularly eye-popping juxtaposition with the unstained interior, almost like cracking open a timber geode to reveal a world of light burning inside.

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

[Image: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photo by Jesper Balleby].

Here’s some more information, from the all-lowercase designboom:

five different volumes have been established, each varying in size and function, while maintaining a consistent spatial relationship. the asymmetric forms are reminiscent of the various shelter types originating from the traditional huts used by fishermen to store their catch, and thus, influencing the names of each one: ‘monkfish’—containing 3 levels and integrated bird-watching platform; ‘garfish’—a 6-7 person overnight shelter that doubles as picnic space for school classes; ‘lumpfish’—a 3-5 person overnight shelter with stay and sauna space; the ‘flounder’—a 2 person overnight shelter; and finally the ‘eelpout’—which functions as the lavatory.

You can see many of those variant types here, but click through to the architects’ website or to designboom for more.

[Images: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photos by Jesper Balleby].

[Images: Shelters by LUMO Architects; photos by Jesper Balleby].

(Via designboom).