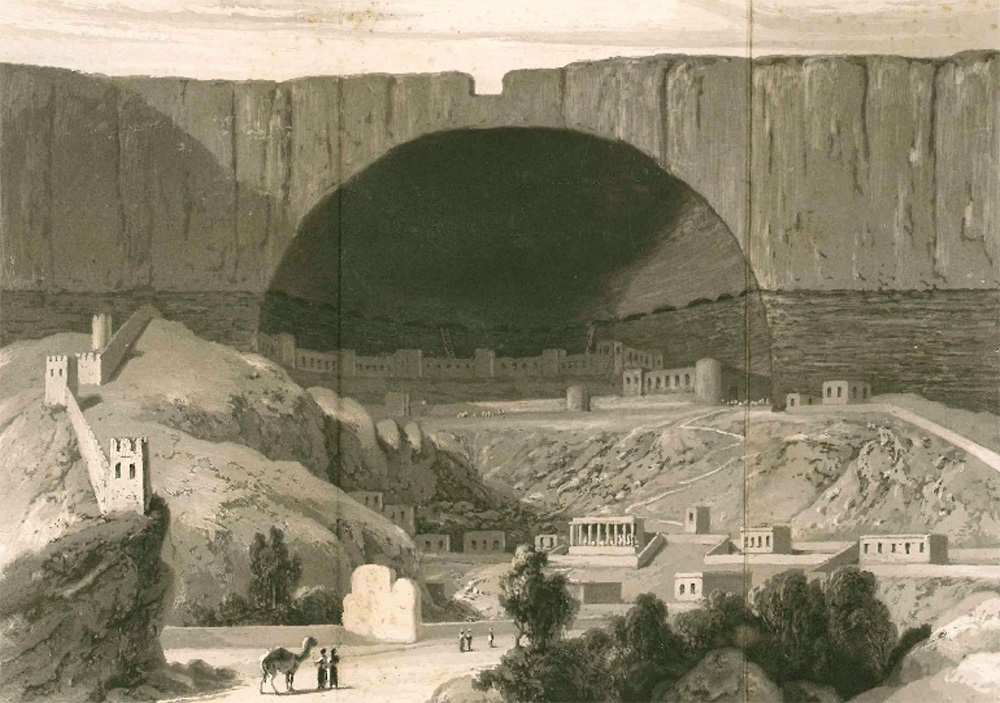

[Image: Here’s another image from the same French rare-book seller seen in an earlier post; this one comes from Thomas Alcock’s Travels in Russia, Persia, Turkey and Greece, printed in 1831. The scene depicted here equally resembles some strange act of theatrical scenography—a geologic backdrop shaded to resemble urban space—and a horizon-spanning speculative megastructure by Étienne Louis-Boullée (previously)].

[Image: Here’s another image from the same French rare-book seller seen in an earlier post; this one comes from Thomas Alcock’s Travels in Russia, Persia, Turkey and Greece, printed in 1831. The scene depicted here equally resembles some strange act of theatrical scenography—a geologic backdrop shaded to resemble urban space—and a horizon-spanning speculative megastructure by Étienne Louis-Boullée (previously)].

Tag: Landscape

A Well-Tailored Landscape

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of Kit Up!].

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of Kit Up!].

Earlier this summer, packaging and apparel manufacturing firm ReadyOne Industries debuted a new line of products: “moldable camouflage kits that can be customized to mimic virtually any type of rock formation or similar type of terrain.”

The sewn geological forms seen here—in photos taken by Matthew Cox of Kit Up!—use a multi-spectral concealment system called “VATEC,” further described by ReadyOne as a “Portable Battlefield Cryptic Signature and Concealment” system.

In the process, they give the word “geotextile” a new level of literality.

[Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of Kit Up!].

[Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of Kit Up!].

While you can read a tiny bit more about the product over at both Kit Up! and ReadyOne, what interests me here is the sheer surreality of portable artificial geology made by a garment manufacturing firm, or pieces of clothing blown up to the scale of landscape.

The unexpected implication is that those rocks you see all around you might not only be fake—they might also be pieces of clothing: camouflage garments that already mimicked natural forms simply taken to their obvious end point in the form of pop-up rocks and well-tailored geology.

Village Design as Magnetic Storage Media

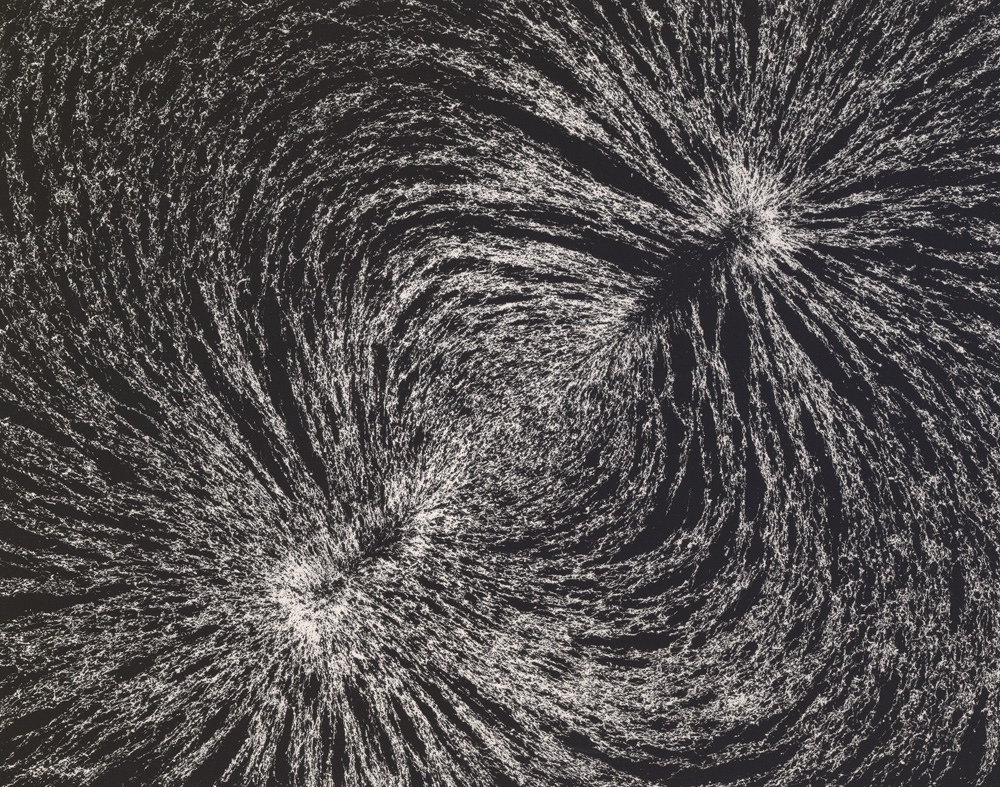

[Image: “Magnetic Field” by Berenice Abbott, from The Science Pictures (1958-1961)].

[Image: “Magnetic Field” by Berenice Abbott, from The Science Pictures (1958-1961)].

An interesting new paper suggests that the ritual practice of burning parts of villages to the ground in southern Africa had an unanticipated side-effect: resetting the ground’s magnetic data storage potential.

As a University of Rochester press release explains, the “villages were cleansed by burning down huts and grain bins. The burning clay floors reached a temperature in excess of 1000ºC, hot enough to erase the magnetic information stored in the magnetite and create a new record of the magnetic field strength and direction at the time of the burning.”

What this meant was that scientists could then study how the Earth’s magnetic field had changed over centuries by comparing more recent, post-fire alignments of magnetite in the ground beneath these charred building sites with older, pre-fire clay surrounding the villages.

The ground, then, is actually an archive of the Earth’s magnetic field.

If you picture this from above—perhaps illustrated as a map or floor plan—you can imagine seeing the footprint of the village itself, with little huts, buildings, and grain bins appearing simply as the outlines of open shapes.

However, within these shapes, like little windows in the surface of the planet, new magnetic alignments would begin to appear over decades as minerals in the ground slowly re-orient themselves with longterm shifts in the Earth’s magnetic field, like differently tiled geometries contrasting with the ground around them.

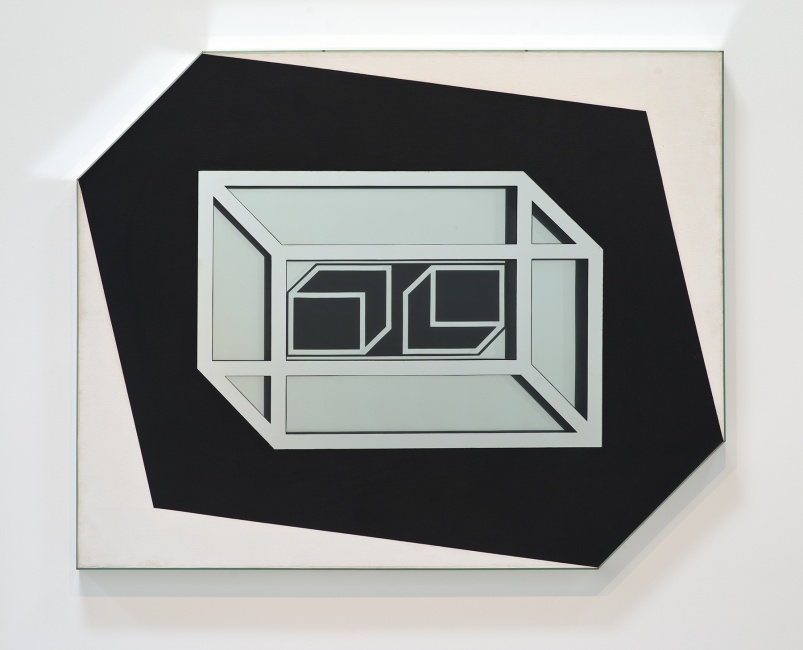

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the L.A. Times].

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the L.A. Times].

What really blows me away here, though, is the much more abstract idea that the ground itself is a kind of reformattable magnetic data storage system. It can be reformatted and overwritten, its data wiped like a terrestrial harddrive.

While this obviously brings to mind the notion of the planetary harddrive we explored a few years ago—for what it’s worth, one of my favorite posts here—it also suggests something quite strange, which is that landscape architecture (that is, the tactical and aesthetic redesign of terrain) and strategies of data management (archiving, cryptography, inscription) might someday go hand in hand.

(Via Archaeology).

Driving on Mars and the Theater of Machines

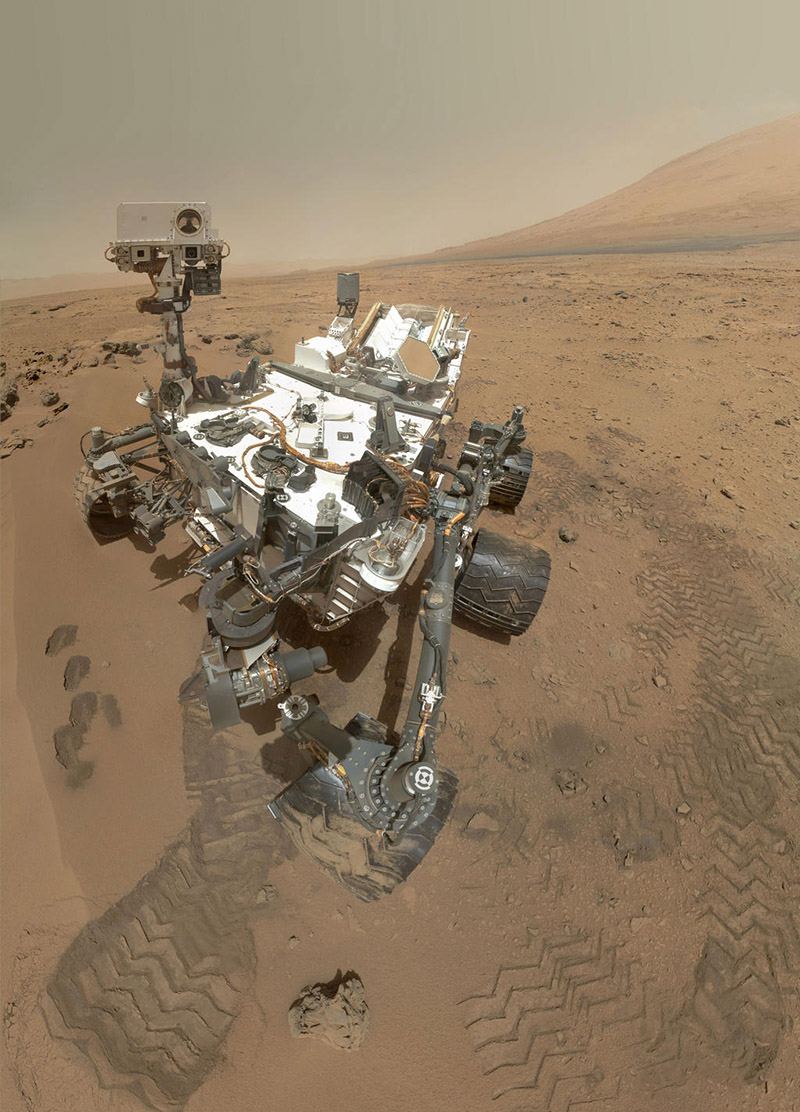

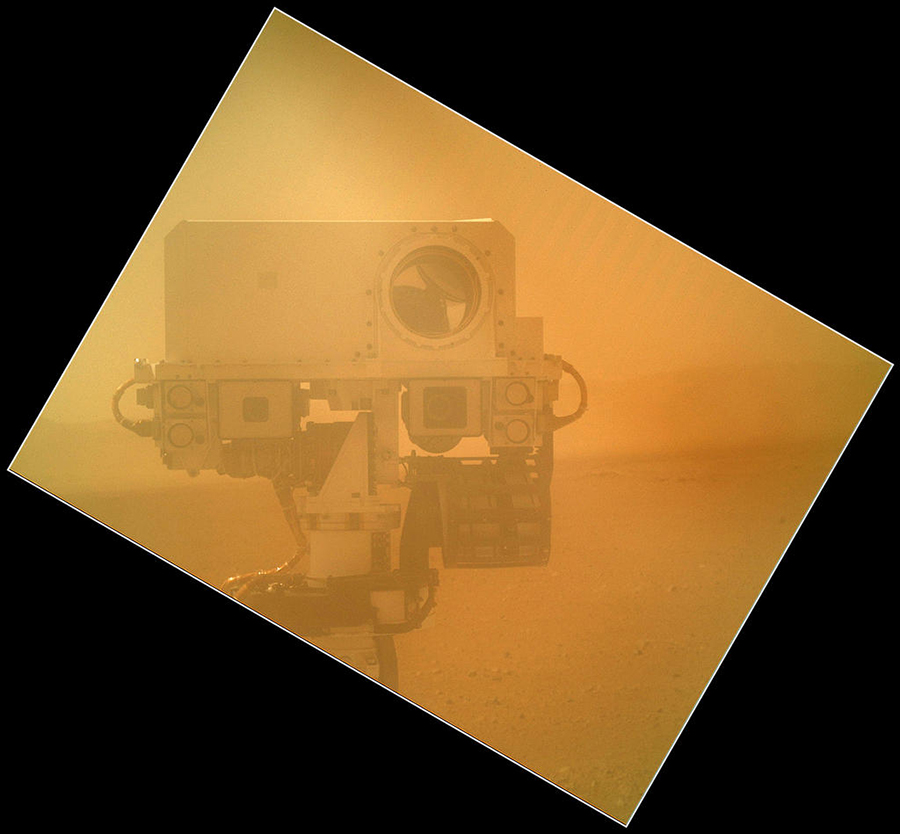

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via NASA].

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via NASA].

Science has published a short profile of a woman named Vandi Verma. She is “one of the few people in the world who is qualified to drive a vehicle on Mars.”

Vera has driven a series of remote vehicles on another planet over the years, including, most recently, the Curiosity rover.

[Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via NASA].

[Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via NASA].

Driving it involves a strange sequence of simulations, projections, and virtual maps that are eventually beamed out from planet to planet, the robot at the other end acting like a kind of wheeled marionette as it then spins forward along its new route. Here is a long description of the process from Science:

Each day, before the rover shuts down for the frigid martian night, it calls home, Verma says. Besides relaying scientific data and images it gathered during the day, it sends its precise coordinates. They are downloaded into simulation software Verma helped write. The software helps drivers plan the rover’s route for the next day, simulating tricky maneuvers. Operators may even perform a dry run with a duplicate rover on a sandy replica of the planet’s surface in JPL’s Mars Yard. Then the full day’s itinerary is beamed to the rover so that it can set off purposefully each dawn.

What’s interesting here is not just the notion of an interplanetary driver’s license—a qualification that allows one to control wheeled machines on other planets—but the fact that there is still such a clear human focus at the center of the control process.

The fact that Science‘s profile of Verma begins with her driving agricultural equipment on her family farm in India, an experience that quite rapidly scaled up to the point of guiding rovers across the surface of another world entirely, only reinforces the sense of surprise here—that farm equipment in India and NASA’s Mars rover program bear technical similarities.

They are, in a sense, interplanetary cousins, simultaneously conjoined and air-gapped across two worlds..

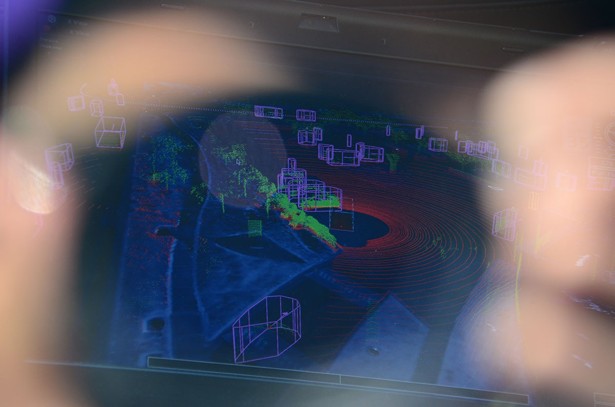

[Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by Alexis Madrigal, courtesy of The Atlantic].

[Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by Alexis Madrigal, courtesy of The Atlantic].

Compare this to the complex process of programming and manufacturing a driverless vehicle. In an interesting piece published last summer, Alexis Madrigal explained that Google’s self-driving cars operate inside a Borgesian 1:1 map of the physical world, a “virtual track” coextensive with the landscape you and I stand upon and inhabit.

“Google has created a virtual world out of the streets their engineers have driven,” Madrigal writes. And, like the Mars rover program we just read about, “They pre-load the data for the route into the car’s memory before it sets off, so that as it drives, the software knows what to expect.”

The software knows what to expect because the vehicle, in a sense, is not really driving on the streets outside Google’s Mountain View campus; it is driving in a seamlessly parallel simulation of those streets, never leaving the world of the map so precisely programmed into its software.

Like Christopher Walken’s character in the 1983 film Brainstorm, Google’s self-driving cars are operating inside a topographical dream state, we might say, seeing only what the headpiece allows them to see.

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from Brainstorm; (bottom) a Google self-driving car, via Google and re:form].

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from Brainstorm; (bottom) a Google self-driving car, via Google and re:form].

Briefly, recall a recent essay by Karen Levy and Tim Hwang called “Back Stage at the Machine Theater.” That piece looked at the atavistic holdover of old control technologies—such as steering wheels—in vehicles that are actually computer-controlled.

There is no need for a human-manipulated steering wheel, in other words, other than to offer a psychological point of focus for the vehicle’s passengers, to give them the feeling that they can still take over.

This is the “machine theater” that the title of their essay refers to: a dramaturgy made entirely of technical interfaces that deliberately produce a misleading illusion of human control. These interfaces are “placebo buttons,” they write, that transform all but autonomous technical systems into “theaters of volition” that still appear to be under manual guidance.

I mention this essay here because the Science piece with which this post began also explains that NASA’s rover program is being pushed toward a state of greater autonomy.

“One of Verma’s key research goals,” we read, “has been to give rovers greater autonomy to decide on a course of action. She is now working on a software upgrade that will let Curiosity be true to its name. It will allow the rover to autonomously select interesting rocks, stopping in the middle of a long drive to take high-resolution images or analyze a rock with its laser, without any prompting from Earth.”

[Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via NASA].

[Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via NASA].

The implication here is that, as the Mars rover program becomes “self-driving,” it will also be transformed into a vast “theater of volition,” in Levy’s and Hwang’s formulation: that Earth-bound “drivers” might soon find themselves reporting to work simply to flip placebo levers and push placebo buttons as these vehicles go about their own business far away.

It will become more ritual than science, more icon than instrument—a strangely passive experience, watching a distant machine navigate simulated terrain models and software packages coextensive with the surface of Mars.

Touring the Gruen Transfer

[Image: Gruen Day 2015].

[Image: Gruen Day 2015].

One of the most interestingly sinister things I studied a million years ago while writing an undergraduate thesis about shopping and agoraphobia is the so-called “Gruen transfer.”

Named after Victor Gruen, pioneer of American shopping mall design, the Gruen transfer is the moment at which, confronted by an unexpected array of choices—other products, rival goods, similar services, different options—a shopper loses sight of what he or she originally came out to purchase. That shopper originally just wanted new socks; now he wants jeans, a t-shirt, and, oh, that coffee place across the hall is looking mighty tempting right now…

The shopper’s desire has been transferred, against their will, onto another item altogether—and this transfer is a deliberately cultivated, if not entirely predictable, side-effect of how the shopping space itself has been designed.

I say “shopping space” rather than “shopping mall,” because the Gruen transfer is clearly alive and well and living online: speaking only from personal experience, the amount of random add-ons I’ve thrown into an Amazon cart at the last minute over the years, or even the extra songs I’ve bought on Bandcamp, is testament to how easy it can be to convince oneself that something you had no idea you were searching for is suddenly a must-have.

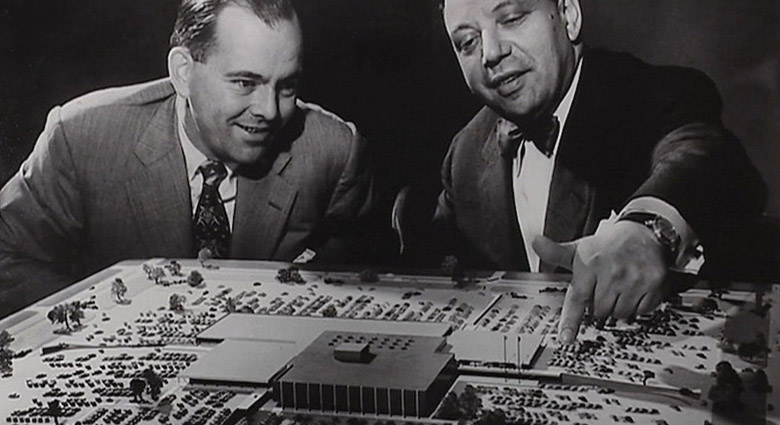

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

What was infinitely more interesting to me, however, was the fact that, when taken to an interpretive extreme, becoming hyper-aware of the possibility that the Gruen transfer might be influencing you can lead to a strange, not particularly enjoyable state of paranoia, in which every decision you make—after all, you went to the mall to buy socks, but perhaps even wanting socks was the result of a Gruen transfer, one that began in the peace of your own home, for example, when you first noticed that you would need new shoes in another month or two, only to realize that, hey, a new pair of socks right now would be awesome… You’ve been transferred.

This can be true whether or not it even involves a purchase. Making the decision to move to a new city, or going to a museum there with a new friend, or even having that new friend in your life in the first place—these all might actually be the end results of multiple, cultivated mis-steps, a much more sinister and far-reaching Gruen transfer as you were silently but comprehensively duped by the world around you.

Pushed to this level, the Gruen transfer takes on a weird, paranoid ubiquity, a disturbing omnipresence that appears to be coextensive with desire in the first place. We are, in a sense, always and already being Gruen transferred, making decisions in a state of otherwise undetectable distraction.

In any case, Victor Gruen’s spatial contribution to the American landscape—how he influenced urban form and set a multi-generational path for the design of retail environments—is the subject of a new tour hosted by the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory. July 18, 2015, is Gruen Day 2015:

Victor Gruen (July 18, 1903–Feb 14, 1980) was an Austrian-born visionary architect most remembered for his pioneering work popularizing the enclosed, climate-controlled shopping center in the United States.

On July 18, the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory (BAIO) invites you to celebrate the lofty aspirations and historical legacy of the suburban shopping center at Gruen Day 2015.

Festivities will include an afternoon of talks, tours, and hanging out in the food court at Bay Fair Center, which opened in 1957 as one of the first Gruen designed shopping centers in the country.

Tickets are $30—but the first ten people to email event co-organizer Tim Hwang saying that you read about the tour on BLDGBLOG will get a free ticket. Email him at tim (at) infraobservatory (dot) com, and tell him I said hey.

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via The Fox is Black].

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via The Fox is Black].

This is technically irrelevant, meanwhile, but it is nonetheless worth remembering that science fiction author Ray Bradbury—whose house of half a century was torn down by, of all people, architect Thom Mayne of Morphosis— claimed to have invented the indoor shopping mall.

Indeed, Bradbury recommended “giant malls as the cure to American urban decay,” Steve Rose explains in The Guardian. “‘Malls are substitute cities,’ [Bradbury] said at the time, ‘substitutes for the possible imagination of mayors, city councilmen and other people who don’t know what a city is while living right in the center of one. So it is up to corporations, creative corporations, to recreate the city.'”

In an essay posthumously published by The Paris Review, Bradbury anecdotally recounted a conversation he once had with architect Jon Jerde. Jerde asked Bradbury if he had ever visited a mall called the Glendale Galleria:

I said, “Yes, I have.” “Did you like it?” he asked. I said, “Yes.” He said, “That’s your Galleria. It’s based on the plans that you put in your article in the essay in the Los Angeles Times.” I was stunned. I said, “Are you telling me the truth? I created the Glendale Galleria?” “Yes, you did,” he said. “Thank you for that article that you wrote about rebuilding L.A. We based our building of the Glendale Galleria completely on what you wrote in that article.”

What Bradbury wrote in that article was the idea that the vast interiors of future shopping malls would supply ersatz urban landscapes “where people could spend an afternoon, getting safely lost, just wandering about.”

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

It was a psychogeography of the interior, as weary shoppers tracked whatever down-market dérive they could find amidst the mirrored escalators and mannequins.

Who knows if Ray Bradbury will come up during Gruen Day 2015, but be sure report back if you take the tour; be sure to email Tim Hwang if you’d like a free ticket.

Lost Highways

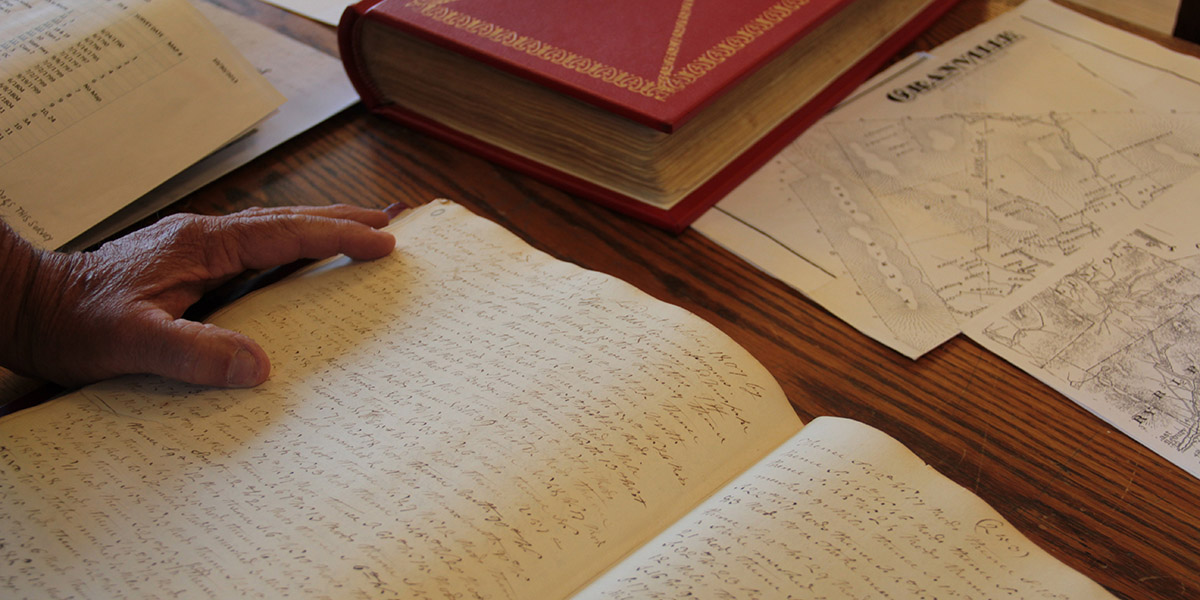

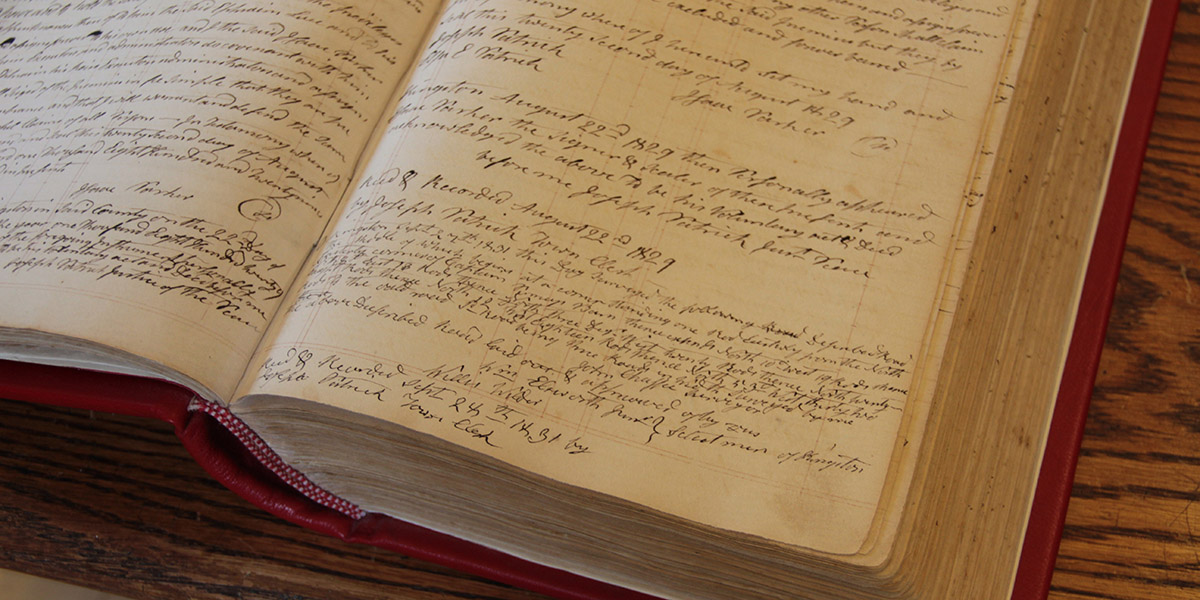

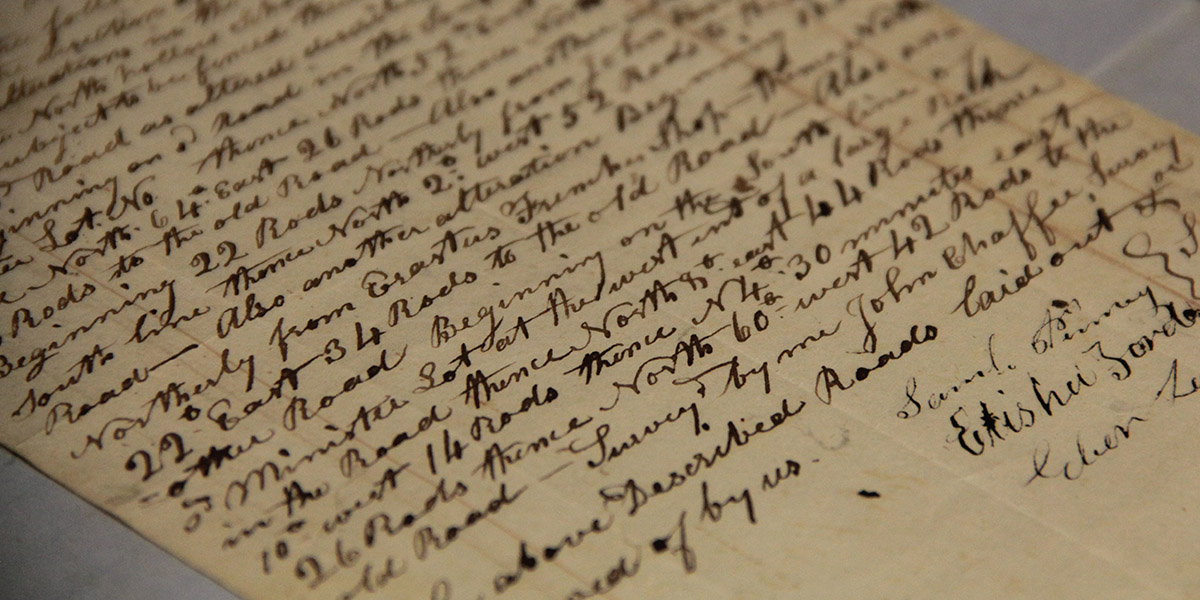

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

A story I’ve been obsessed with since first learning about it back in 2008 is the problem of “ancient roads” in Vermont.

Vermont is unusual in that, if a road has been officially surveyed and, thus, added to town record books—even if that road was never physically constructed—it will remain legally recognized unless it has been explicitly discontinued.

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

This means that roads surveyed as far back as the 1790s remain present in the landscape as legal rights of way—with the effect that, even if you cannot see this ancient road cutting across your property, it nonetheless persists, undercutting your claims to private ownership (the public, after all, has the right to use the road) and making it difficult, if not impossible, to obtain title insurance.

Faced with a rising number of legal disputes from homeowners, Vermont passed Act 178 back in 2006. Act 178 was the state’s attempt to scrub Vermont’s geography of these dead roads.

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

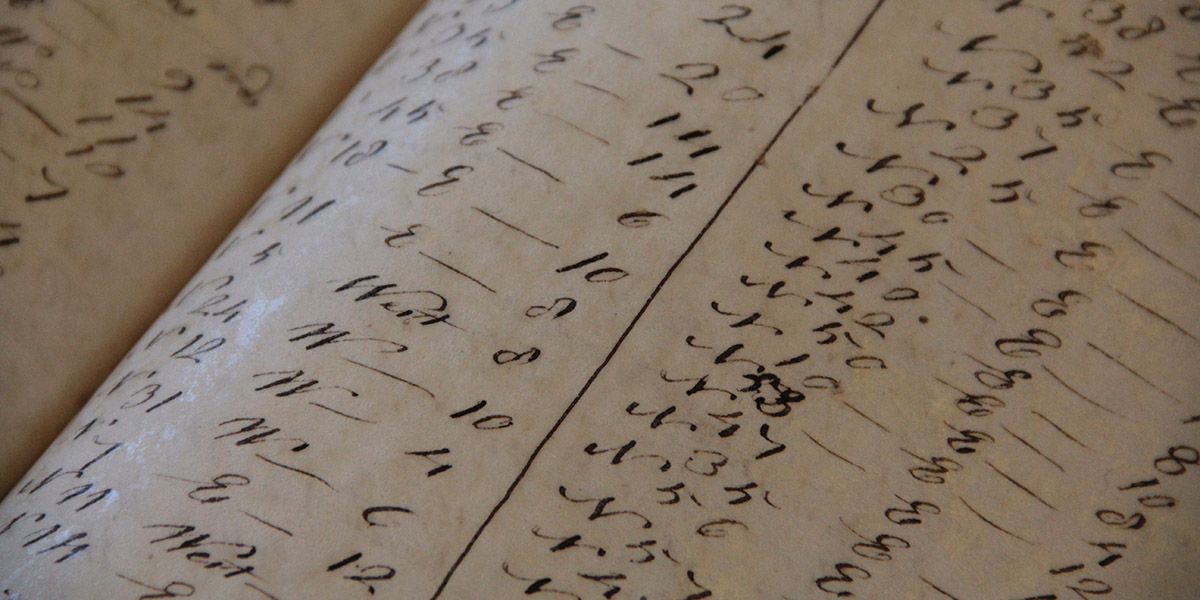

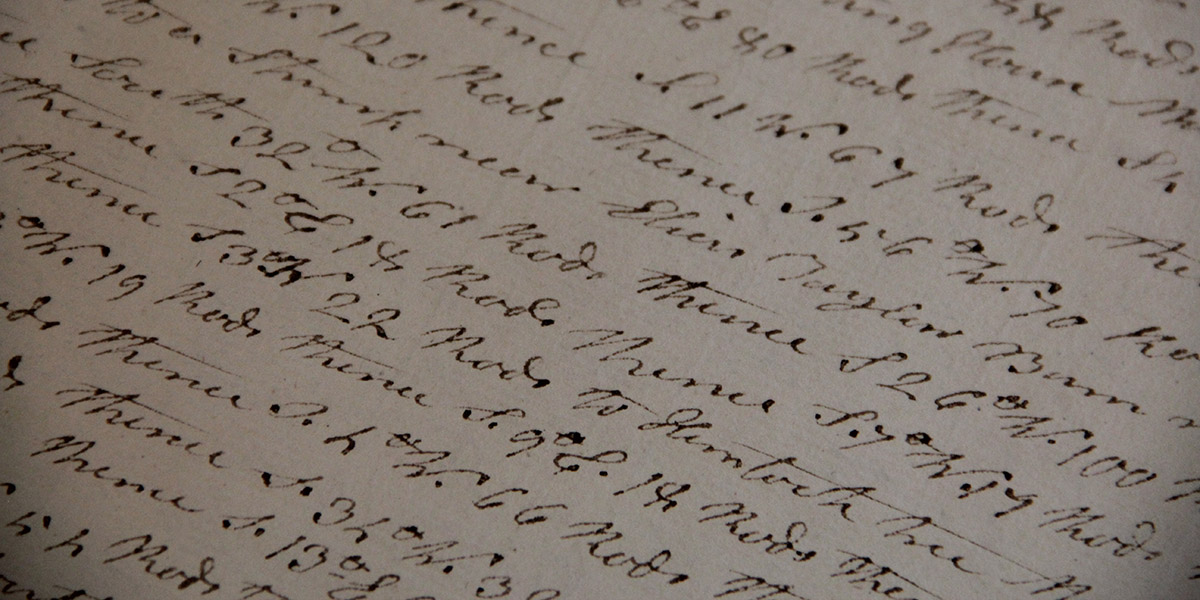

The Act’s immediate effects, however, were to kick off a rush of new research into the state’s lost roadways.

This meant going back through property deeds and mortgage records, dating back to the late 18th-century, deciphering old handwriting, making sense of otherwise location-less survey coordinates, and then reconciling all this with on-the-ground geologic features or local landmarks.

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

Not every town was enthusiastic about finding them, hoping instead that the old roads would simply disappear.

Other towns—and specific townspeople—responded with far more enthusiasm, as if finding an excuse to rediscover their own histories, the region’s past, and the lives of the other families or settlers who once lived there.

Anything they found and officially submitted for inclusion on Vermont’s state highway map would continue to exist as a state-recognized throughway; anything left undocumented, or specifically called out for discontinuance, would disappear, losings its status as a road and becoming mere landscape.

July 1, 2015, was the deadline, after which anything left undiscovered is meant to remain undiscovered.

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

I had an amazing opportunity to visit the tiny town of Granville, Vermont, ten days ago, where I met with a retired forester and self-enlisted local historian named Norman Arseneault.

Arseneault became so involved in the search for Granville’s ancient roads that he is not only self-publishing an entire book documenting his quest, but he was also pointed out to me as an exemplar of rigor and organization by Johnathan Croft, chief of the Mapping Section at the Vermont Agency of Transportation (where there is an entire page dedicated to “Ancient Roads“).

His hunt for old roads seems to fall somewhere between Robert Macfarlane’s recent work and the old Western trail research of Glenn R. Scott.

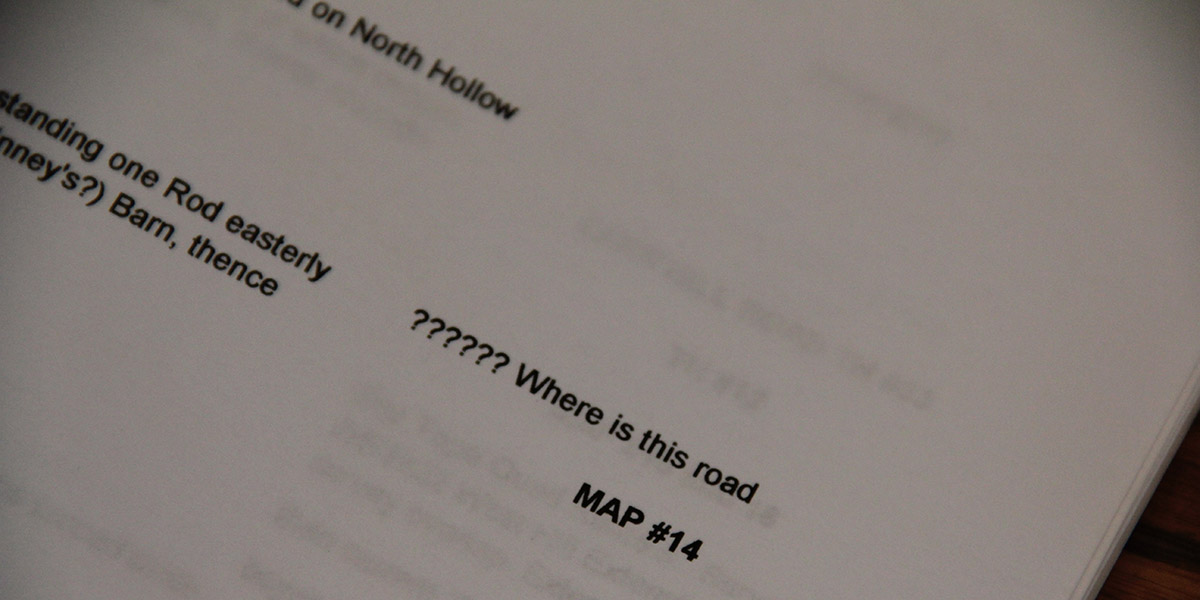

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

While I was there in Granville, Arseneault took me into the town vault, flipping back through nearly 225 years of local property deeds. We then hit the old forest roads in his pick-up truck, to hike many of the “ancient roads” his research had uncovered.

I wrote up the whole experience for The New Yorker, and I have to say it was one of the more interesting article research processes I’ve ever been involved with; check it out, if any of this sounds of interest.

It’s worth pointing out, meanwhile, that the problem of “ancient roads” is not, in fact, likely to go away; the recent introduction of LiDAR data, on top of some confusingly written legal addenda, make it all but certain that other property owners will yet find long-forgotten public routes crossing their land, or that a future private development count still find its unbuilt plots placed squarely atop invisible roads made newly available to town use.

The hows and whys of this are, I hope, explained a bit more over at The New Yorker.

A Vast Array of Props

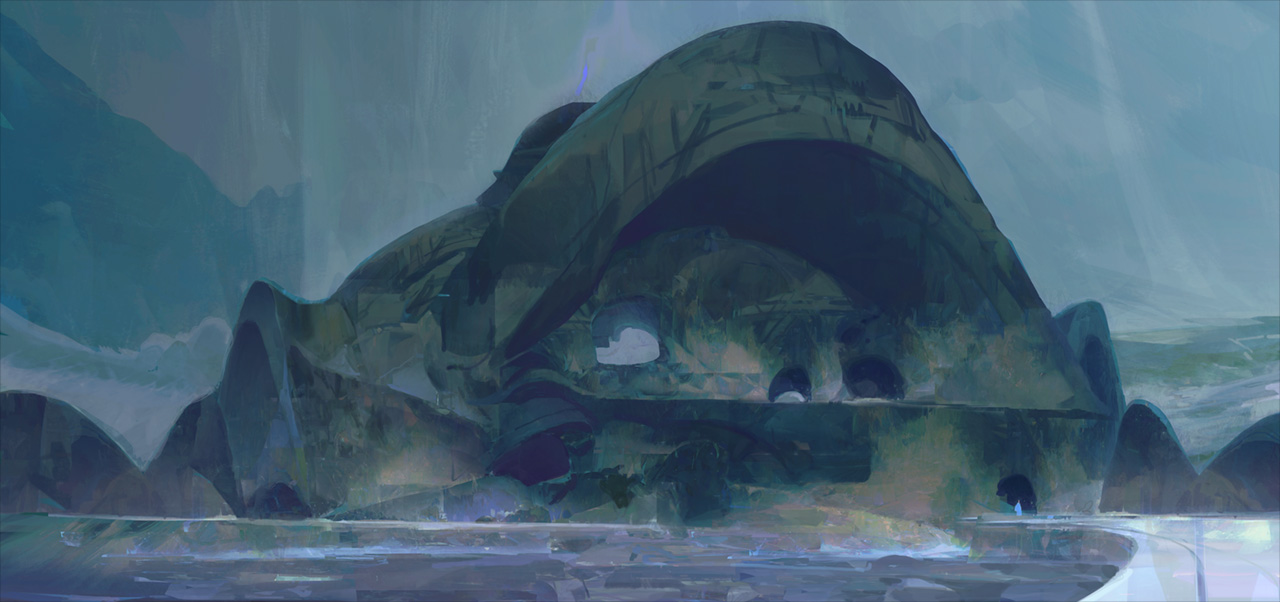

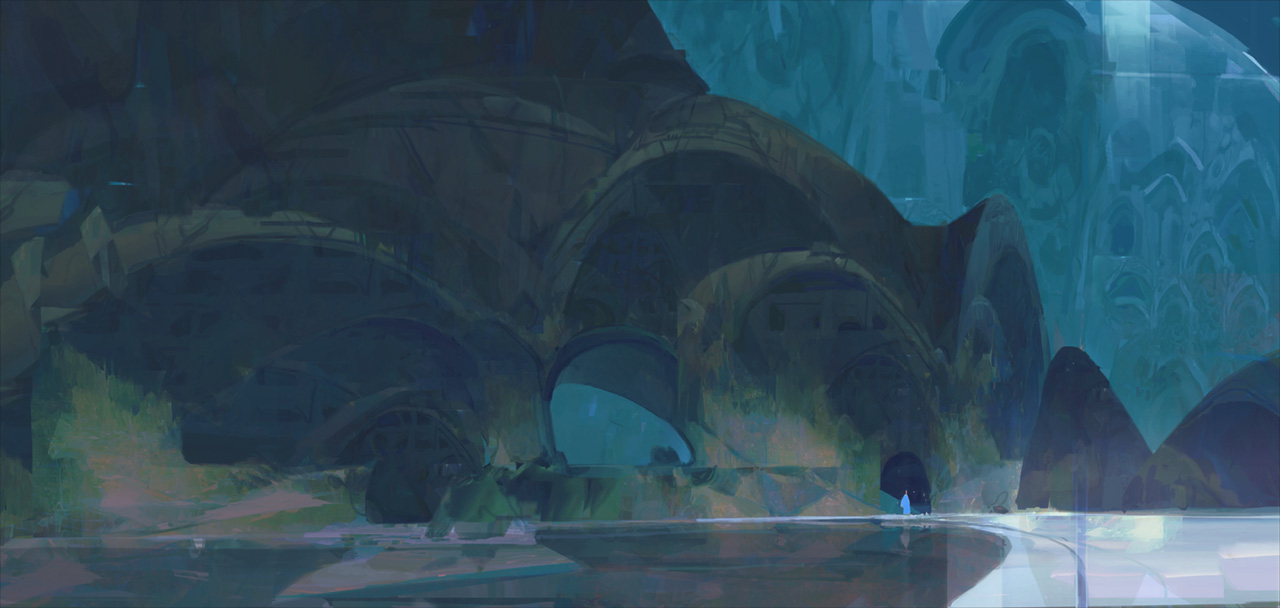

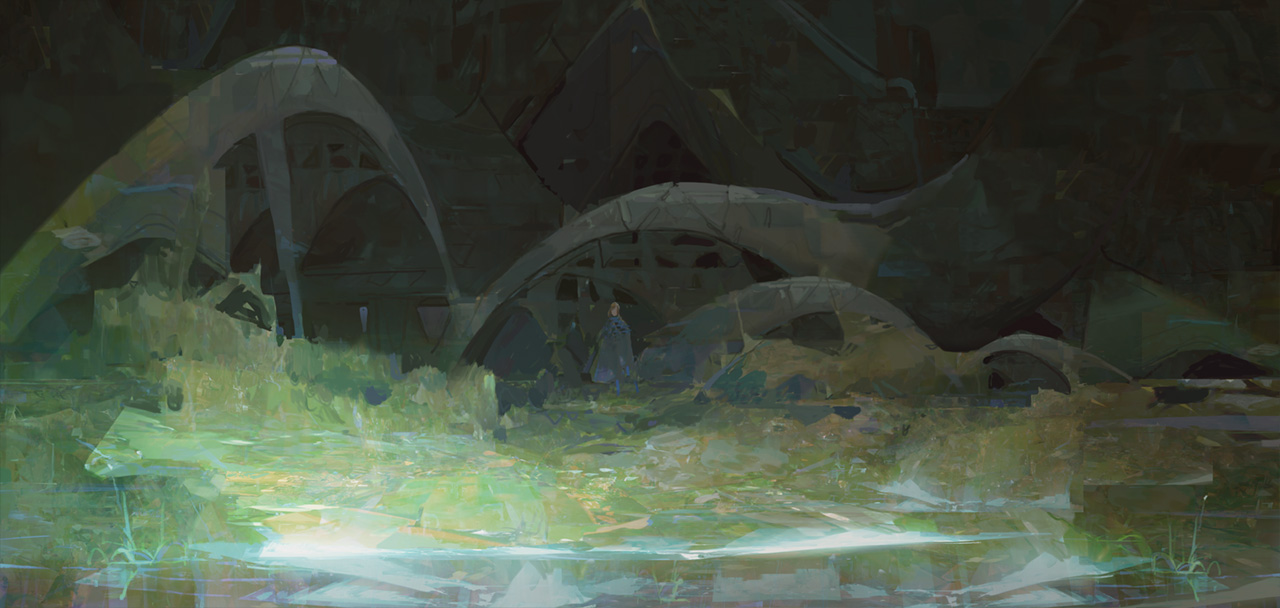

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

Rock, Paper, Shotgun has posted an interview with artist Thomas Scholes about “how concept art is made.”

Scholes refers to himself as “an environment specialist,” and he describes how he develops the architecture and landscapes for games such as Guild Wars 2, Halo 4, Gigantic, and many others.

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

One of his many strategies is to develop what RPS calls “a vast array of props”: Scholes, we read, has “constructed huge asset sets from which he can plunder. A previous month-long project of his was to create a vast array of props, which he can now deposit in his images and rework to give a sense of clutter.”

These include architectural motifs—arches, walls, stone monoliths, ruins—that are often just reworked from previous backgrounds. For these, he will “repurpose bits of previous paintings, manipulating their shape to suggest a receding wall, ceiling or floor.”

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, Sketch a Day series; view larger].

Scholes recently embarked on a “sketch a day” project that produced the images you see here. The sketches are left rough, or, as RPS suggest, they “resist the instinct to over-define, to steer them away from pedantic perfectionism.”

This often makes his images both impressionistic and painterly, emotive explorations of gothic terrains and environments.

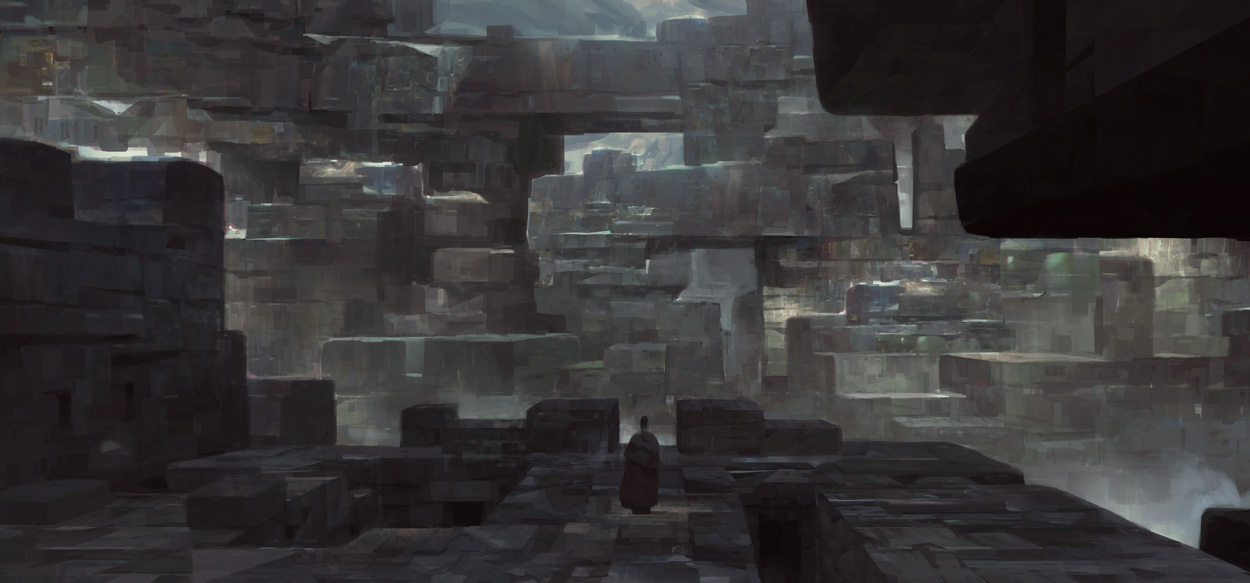

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

Many of these images are frankly gorgeous, including vibrant forest landscapes that would not look out of place in an exhibition of 18th-century landscape painting—or even alongside examples from the Hudson River School or the work of Caspar David Friedrich.

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

These being games, of course, rather than the Rückenfigur of Friedrich, you’ve got cloaked figures peering into hostile and mysterious landscapes, looking not for aesthetic solace but for hidden strategic advantages, ready for combat.

[Images: Thomas Scholes, Oppidum; view larger].

[Images: Thomas Scholes, Oppidum; view larger].

In any case, check out the interview over at Rock, Paper, Shotgun or, even better, click around Scholes’s website for a lot more images like these.

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

[Image: Thomas Scholes, miscellaneous work; view larger].

[Previously on BLDGBLOG: Game/Space: An Interview with Daniel Dociu].

The Town That Creep Built

[Image: A curb in Hayward reveals how much the ground is drifting due to “fault creep”: the red-painted part is slowly, but relentlessly, moving north. Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A curb in Hayward reveals how much the ground is drifting due to “fault creep”: the red-painted part is slowly, but relentlessly, moving north. Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

South of San Francisco, a whole town is being deformed by plate tectonics. These are the slow but relentless landscape effects known as “fault creep.”

The signs that something’s not right aren’t immediately obvious, but, once you see them, they’re hard to tune out.

Curbs at nearly the exact same spot on opposite sides of the street are popped out of alignment. Houses too young to show this level of wear stand oddly warped, torqued out of synch with their own foundations, their once strong frames off-kilter. The double yellow lines guiding traffic down a busy street suddenly bulge northward—as if the printing crew came to work drunk that day—before snapping back to their proper place a few feet later.

This is Hollister, California, a town being broken in two slowly, relentlessly, and in real time by an effect known as “fault creep.” A surreal tide of deformation has appeared throughout the city.

[Image: “Fault creep” bends the curbs in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “Fault creep” bends the curbs in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

As if its grid of streets and single-family homes was actually built on an ice floe, the entire west half of Hollister is moving north along the Calaveras Fault, leaving its eastern streets behind.

In some cases, doors no longer fully close and many windows now open only at the risk of getting stuck (some no longer really close at all).

Walking through the center of town near Dunne Park offers keen observers a hidden funfair of skewed geometry.

[Image: 359 Locust Avenue, Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: 359 Locust Avenue, Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

For example, go to the house at 359 Locust Avenue.

The house itself stands on a different side of the Calaveras Fault than its own front walkway. As if trapped on a slow conveyor built sliding beneath the street, the walk is being pulled inexorably north, with the effect that the path is now nearly two feet off-center from the porch it still (for the time being) leads to.

[Image: The walkway is slowly creeping north, no longer centered with the house it leads to; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: The walkway is slowly creeping north, no longer centered with the house it leads to; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

In another generation, if it’s not fixed, this front path will be utterly useless, leading visitors straight into a pillar.

Or walk past the cute Victorian on 5th Street. Strangely askew, it seems frozen at the start of an unexpected metamorphosis.

[Image: Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Photo by Geoff Manaugh].

Geometrically, it’s a cube being forced to become a rhomboid by the movements of the fault it was unknowingly built upon, an architectural dervish interrupted before it could complete its first whirl.

Now look down at your feet at the ridged crack spreading through the asphalt behind you, perfectly aligned with the broken curbs and twisted homes on either side.

This is the actual Calaveras Fault, a slow shockwave of distortion forcing its way through town, bringing architectural mutation along with it.

[Images: The Calaveras Fault pushes its way through Hollister; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: The Calaveras Fault pushes its way through Hollister; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

The ceaseless geometric tumult roiling just beneath the surface of Hollister brings to mind the New Orleans of John McPhee, as described in his legendary piece for The New Yorker, “Atchafalaya.”

There, too, the ground is active and constantly shifting—only, in New Orleans, it’s not north or south. It’s up or down. The ground, McPhee explains, is subsiding.

“Many houses are built on slabs that firmly rest on pilings,” he writes. “As the turf around a house gradually subsides, the slab seems to rise.” This leads to the surreal appearance of carnivalesque spatial side-effects, with houses entirely detached from their own front porches and stairways now leading to nowhere:

Where the driveway was once flush with the floor of the carport, a bump appears. The front walk sags like a hammock. The sidewalk sags. The bump up to the carport, growing, becomes high enough to knock the front wheels out of alignment. Sakrete appears, like putty beside a windowpane, to ease the bump. The property sinks another foot. The house stays where it is, on its slab and pilings. A ramp is built to get the car into the carport. The ramp rises three feet. But the yard, before long, has subsided four. The carport becomes a porch, with hanging plants and steep wooden steps. A carport that is not firmly anchored may dangle from the side of a house like a third of a drop-leaf table. Under the house, daylight appears. You can see under the slab and out the other side. More landfill or more concrete is packed around the edges to hide the ugly scene.

Like McPhee’s New Orleans, Hollister is an inhabitable catalog of misalignment and disorientation, bulging, bending, and blistering as it splits right down the middle.

And there’s more. Stop at the north end of 6th Street, for example, just across from Dunne Park, and look back at the half-collapsed retaining wall hanging on for dear life in front of number 558.

It looks like someone once backed a truck into it—but it’s just evidence of plate tectonics, the ground bulging northward without regard for bricks or concrete.

[Images: A fault-buckled wall and sidewalk bearing traces of planetary forces below; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A fault-buckled wall and sidewalk bearing traces of planetary forces below; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

In fact, follow this north on Google Maps and you’ll find a clean line connecting this broken wall to the jagged rupture crossing the street in the photographs above, to the paper-thin fault dividing the house from its own front walk on Locust Avenue.

So what’s happening to Hollister?

“Fault creep” is a condition that results when the underlying geology is too soft to get stuck or to accumulate tectonic stress: in other words, the deep rocks beneath Hollister are slippery, more pliable, and behave a bit like talc. Wonderfully but unsurprisingly, the mechanism used to study creep is called a creepmeter.

The ground sort of oozes past itself, in other words, a slow-motion landslide at a pace that would be all but imperceptible if it weren’t for the gridded streets and property lines being bent out of shape above it.

[Image: A curb and street drain popped far out of alignment in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A curb and street drain popped far out of alignment in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

In a sense, Hollister is an urban-scale device for tracking tectonic deformation: attach rulers to its porches and curbs, and you could even take measurements.

The good news is that the large and damaging earthquakes otherwise associated with fault movement—when the ground suddenly breaks free every hundred years or so in a catastrophic surge—are not nearly as common here.

Instead, half a town can move north by more than an inch every five years and all that most residents will ever feel is an occasional flutter.

[Images: Crossing onto the Pacific Plate (heading west) in Parkfield; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: Crossing onto the Pacific Plate (heading west) in Parkfield; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

I spoke with Andy Snyder from the U.S. Geological Survey about the phenomenon.

Snyder works on an experiment known as the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth, or SAFOD, which has actually drilled down through the San Andreas Fault to monitor what’s really happening down there, studying the landscape from below through sensitive probes installed deep in the active scar tissue between tectonic plates.

On Snyder’s advice, I made my way out to one of the greatest but most thoroughly mundane monuments to fault creep in the state of California. This was in Parkfield, a remote town with a stated population of 18 where Snyder and SAFOD are both based, and where fault creep is particularly active.

In Parkfield there is a remarkable road bridge: a steel structure that has been anchored to either side of the San Andreas Fault like a giant, doomed staple. Anyone who crosses it in either direction is welcomed onto a new tectonic plate by friendly road signs—but the bridge itself is curiously bent, warped like a bow as its western anchorage moves north toward San Francisco.

It distorts more and more every day of the month, every year, due to the slow effects of fault creep. Built straight, it is already becoming a graceful curve.

[Image: Looking east at the North American Plate in Parkfield; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Looking east at the North American Plate in Parkfield; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

Parkfield is also approximately where fault creep begins in the state, Snyder explained, marking the southern edge of a zone of tectonic mobility that extends up roughly to Hollister and then begins again on a brief stretch of the Hayward Fault in the East Bay.

Indeed, another suggestion of Snyder’s was that I go up to visit a very specific corner in the city of Hayward, where the curb at the intersection of Rose and Prospect Streets has long since been shifted out of alignment.

Over the past decade—most recently, in 2011—someone has actually been drawing little black arrows on the concrete to help visualize how far the city has drifted in that time.

The result is something like an alternative orientation point for the city, a kind of seismic meridian—or perhaps doomsday clock—by which Hayward’s ceaseless cleaving can be measured.

[Images: A moving curb becomes an inadvertent compass for measuring seismic energy in Hayward; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

[Images: A moving curb becomes an inadvertent compass for measuring seismic energy in Hayward; photos by Geoff Manaugh].

Attempting to visualize earthquakes on a thousand-year time span, or to imagine the pure abstraction of seismic energy, can be rather daunting; this makes it all the more surprising to realize that even the tiniest details hidden in plain sight, such as cracks in the sidewalk, black sharpie marks on curbs, or lazily tilting front porches, can actually be real-time evidence that California is on the move.

But it is exactly these types of signs that function as minor landmarks for the seismic tourist—and, for all their near-invisibility, visiting them can still provide a mind-altering experience.

Back in Hollister, Snyder warned, many of these already easily missed signs through which fault creep is made visible are becoming more and more hard to find.

The town is rapidly gentrifying, he pointed out, and Hollister’s population is beginning to grow as its quiet and leafy streets fill up with commuters who can no longer afford to live closer to Silicon Valley or the Bay. This means that the city’s residents are now just a bit faster to repair things, just a bit quicker to tear down structurally unsound houses.

One of the most famous examples of fault creep, for example—a twisted and misshapen home formerly leaning every which way at a bend in Locust Avenue—is gone. But whatever replaces it will face the same fate.

After all, the creep is still there, like a poltergeist disfiguring things from below, a malign spirit struggling to make itself visible.

Beneath the painted eaves and the wheels of new BMWs, the landscape is still on the move; the deformation is just well hidden, a denied monstrosity reappearing millimeter by millimeter despite the quick satisfaction of weekend repair jobs. Tumid and unstoppable, there is little that new wallpaper or re-poured driveways can do to disguise it.

[Image: Haphazard concrete patchwork in a formerly straight sidewalk betrays the slow action of fault creep; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Haphazard concrete patchwork in a formerly straight sidewalk betrays the slow action of fault creep; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

Snyder remembered one more site in Hollister that he urged me to visit on my way out of town.

In the very center of Hollister’s Dunne Park, a nice and gentle swale “like a chaise longue,” in his words, has been developing.

Expecting to find just a small bump running through the park, I was instead surprised to see that there is actually a rather large grassy knoll forming there, a rolling and bucolic hill that few people would otherwise realize is an active tectonic fault.

[Image: A fault-caused grassy knoll rises in the center of Dunne Park in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: A fault-caused grassy knoll rises in the center of Dunne Park in Hollister; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

In fact, he said, residents have been entirely unperturbed by this mysterious appearance of a brand new landform in the middle of their city, seeing it instead as an opportunity for better sunbathing. Fault creep is not without its benefits, he joked.

Snyder laughed as he described the sight of a dozen people and their beach towels, all angling themselves upward toward the sun, getting tan in a mobile city with the help of plate tectonics.

[Note: An earlier version of this piece was first published on The Daily Beast (where I did not choose the original headline). I owe a huge thanks to Andy Snyder for the phone conversation in which we discussed fault creep; and the book Finding Fault in California: An Earthquake Tourist’s Guide by Susan Elizabeth Hough was also extremely useful. Finally, please also note that, if you do go to Hollister or Hayward to photograph these sites, be mindful of the people who actually live there, as they do not necessarily want crowds of strangers gathering outside their homes].

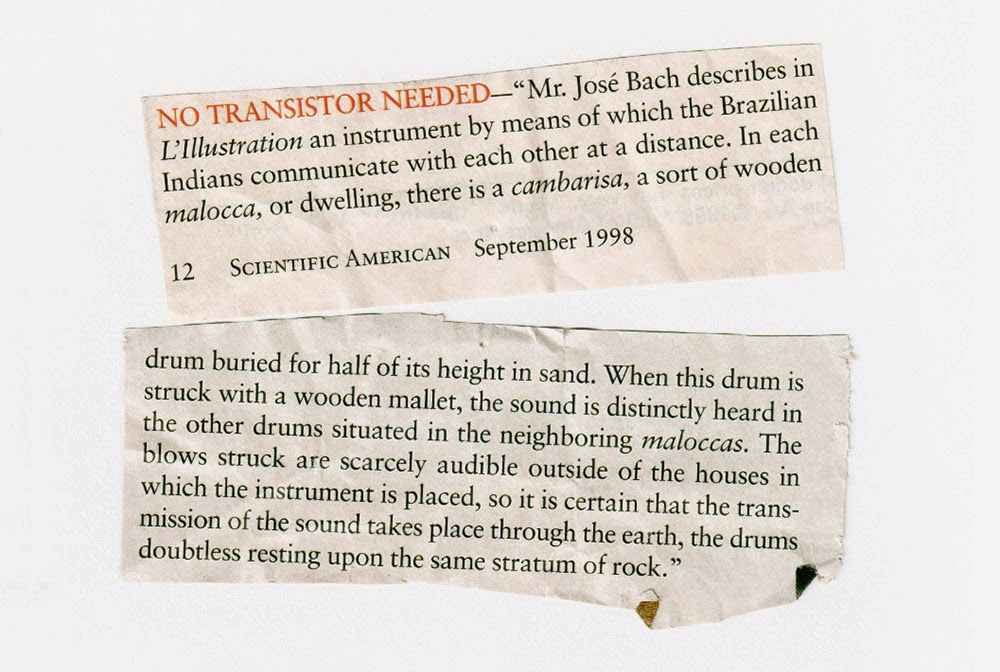

Terrestrial Sonar

I found this thing in my desk again last night, and, as you can tell from the date in the image, below, it’s been following me around since 1998 (!). However, after seventeen years of carrying random clippings like this around in files, folders, drawers, and envelopes—after all, this is only one of many dozens—I decided it was time to get rid of it.

But not before writing a quick post.

[Image: From Scientific American, September 1998].

[Image: From Scientific American, September 1998].

The original article actually appeared in Scientific American way back in their 1898 issue, making the fragment, scanned above, just a snippet published 100 years later.

The original was called “A Brazilian Indian Telephone,” and you can read it over at Archive.org. Here’s the bulk of the story:

Mr. Jose Bach, in a narrative of his travels among the Indians of the regions of the Amazon, describes in L’lllustration an instrument by means of which these people communicate with each other at a distance.

These natives live in groups of from one hundred to two hundred persons, and in dwellings called “maloccas,” which are usually situated at a distance of half a mile or a mile apart. In each malocca there is an instrument called a “cambarisa,” which consists essentially of a sort of wooden drum that is buried for half of its height in sand mixed with fragments of wood, bone, and mica, and is closed with a triple diaphragm of leather, wood, and India rubber.

When this drum is struck with a wooden mallet, the sound is transmitted to a long distance, and is distinctly heard in the other drums situated in the neighboring maloccas. It is certain that the transmission of the sound takes place through the earth, since the blows struck are scarcely audible outside of the houses in which the instruments are placed.

After the attention of the neighboring maloccas has been attracted by a call blow, a conversation may be carried on between the cambarisas designated.

According to Mr. Bach, the communication is facilitated by the nature of the ground, the drums doubtless resting upon one and the same stratum of rock, since transmission through ordinary alluvial earth could not be depended upon.

While, in and of itself, this is pretty awesome, there are at least two quick things that really captivate me here:

1) One is the simple idea that the geology of the forest itself can be instrumentalized and turned into a “telephone” network, in the most literal, etymological sense of that word (voices [-phone] at a distance [tele-]). The landscape itself becomes a percussive grid of underground communication, pounding out messages and warnings from home to home, like submarine captains pinging Morse code to one another in the deep.

It’s fascinating and, in fact, deeply strange to imagine that little rumblings or booms in the soil are actually homes corresponding to one another—and that, given the context, they might actually be talking about you.

2) The other thing is how this could be updated or, as it were, urbanized for today. You go down into the basement to get away from your family, bored of your life, trapped in a house you want to leave, wondering if you’ll ever meet true friends, and you start randomly tapping away on the sump pump, when—lo!—someone actually answers back, skittling out a little rhythm for you from another cellar just up the street. A whole suburb of feral children, drumming messages to each other in the dark, hammering on their basement floors.

It’s like those scenes in old prison flicks, where two men tap back and forth all night on their cell walls, only, here, it’s people banging on cellar floors in New York City high rises or hitting sump pumps with mallets in the wilds of suburbia, speaking back and forth through their own “Brazilian Indian Telephone,” a kind of terrestrial sonar.

(See also: using barbed-wire fences as rural telephones).

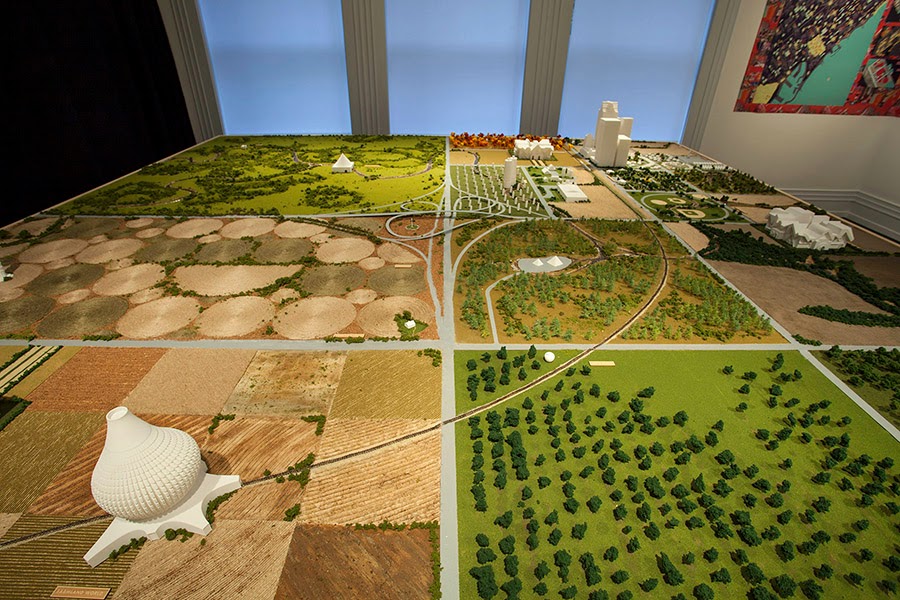

Mathematical Averages and the Landscape of the American Midwest

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

Alas, I did not have a chance to write about this project while it was still on public display last month at the Graham Foundation in Chicago, but Design With Co.—an interesting firm previously featured here for their “Farmland World” proposal—has put together an analytic landscape model called the “Midwestern Culture Sampler.”

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

The idea behind the model was to use “a fictional institutional entity called the Institute for Quantities, Scale and Image” in order to illustrate patterns of land use across the United States.

The resulting model, at ten-and-a-half square-feet, thus showed “a full square mile of the average geography and settlement patterns of the United States in their representative proportions.”

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

In other words, if 27% forest cover, 11% asphalt, 53% agricultural, or any other possible mathematical combination—including number of sports fields, schools, roads, or even hospitals—was the average American use of a given square-acreage of land, then that is how it would be modeled by Design With Co.

This would result in a perfectly calibrated but, for that very reason, utterly absurd representation of the ideal countryside.

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

In fact, the designers’ quest for exact calibration also extended to the architecture itself, which became a cartoonish, postmodern exaggeration of midwestern building styles.

Further, the designers explain, “Within this territory are various landmarks and attractions that are relocated in ways that enhance or challenge their architectural metaphors.”

These include, for example, the “Leaning Tower of Pisa” as rebuilt in Niles, Illinois.

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

An accompanying guidebook, which I have not yet seen, called Mis-Guided Tactics for Propriety Calibration, apparently offers a history of their fictional institution, but perhaps also, as its title suggests, includes a series of instructions for how one’s own land use patterns could brought into mathematical alignment with the national average.

Build another baseball diamond!

[Image: A ghost of “Farmland World” slips into the model… From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

[Image: A ghost of “Farmland World” slips into the model… From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by Design With Co.; photo by Matthew Messner].

Their overall intention, according to the designers, was “to reframe the familiar in a way that begins to feel like a hyper-real fairy tale,” a landscape of exaggerated relationships and distorted terrains that, nonetheless, are mathematically accurate reflections of the country.

I believe the model is now traveling to other venues, so keep your eye out for the American average landscape popping up in a gallery near you.

The Los Angeles County Department of Ambient Music vs. The Superfires of Tomorrow

You might have seen the news last month that two students from George Mason University developed a way to put out fires using sound.

“It happens so quickly you almost don’t believe it,” the Washington Post reported at the time. “Seth Robertson and Viet Tran ignite a fire, snap on their low-rumbling bass frequency generator and extinguish the flames in seconds.”

Indeed, it seems to work so well that “they think the concept could replace the toxic and messy chemicals involved in fire extinguishers.”

There are about a million interesting things here, but I was totally captivated by two points, in particular.

At one point in the video, co-inventor Viet Tran suggests that the device could be used in “swarm robotics” where it would be “attached to a drone” and then used to put out fires, whether wildfires or large buildings such as the recent skyscraper fire in Dubai. But consider how this is accomplished; from the Washington Post:

The basic concept, Tran said, is that sound waves are also “pressure waves, and they displace some of the oxygen” as they travel through the air. Oxygen, we all recall from high school chemistry, fuels fire. At a certain frequency, the sound waves “separate the oxygen [in the fire] from the fuel. The pressure wave is going back and forth, and that agitates where the air is. That specific space is enough to keep the fire from reigniting.”

While I’m aware that it’s a little strange this would be the first thing to cross my mind, surely this same effect could be weaponized, used to thin the air of oxygen and cause targeted asphyxiation wherever these robot swarms are sent next. After all, even something as simple as an over-loud bass line in your car can physically collapse your lungs: “One man was driving when he experienced a pneumothorax, characterised by breathlessness and chest pain,” the BBC reported back in 2004. “Doctors linked it to a 1,000 watt ‘bass box’ fitted to his car to boost the power of his stereo.”

In other words, motivated by a large enough defense budget—or simply by unadulterated misanthropy—you could thus suffocate whole cities with an oxygen-thinning swarm of robot sound systems in the sky. Those “Ride of the Valkyries”-blaring speakers mounted on Robert Duvall’s helicopter in Apocalypse Now might be playing something far more sinister over the battlefields of tomorrow.

However, the other, more ethically acceptable point of interest here is the possible landscape effect such an invention might have—that is, the possibility that this could be scaled-up to fight forest fires. There are a lot of problems with this, of course, including the fact that, even if you deplete a fire of oxygen, if the temperature remains high, it will simply flicker back to life and keep burning.

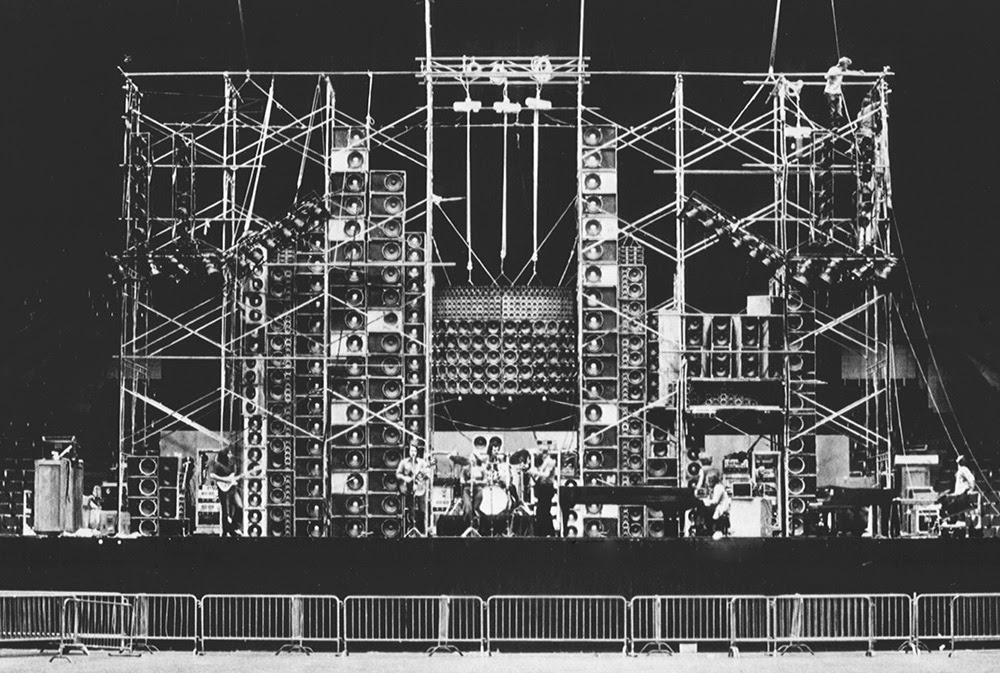

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via audioheritage.org].

[Image: The Grateful Dead “wall of sound,” via audioheritage.org].

Nonetheless, there is something awesomely compelling in the idea that a wildfire burning in the woods somewhere in the mountains of Arizona might be put out by a wall of speakers playing ultra-low bass lines, rolling specially designed patterns of sound across the landscape, so quiet you almost can’t hear it.

A hum rumbles across the roots and branches of burning trees; there is a moment of violent trembling, as if an unseen burst of wind has blown through; and then the flames go out, leaving nothing but tendrils of smoke and this strange acoustic presence buzzing further into the fires up ahead.

Instead of emergency amphibious aircraft dropping lake water on remote conflagrations, we’d have mobile concerts of abstract sound—the world’s largest ambient raves—broadcast through National Parks and on the edges of desert cities.

Desperate, Los Angeles County hires a Department of Ambient Music to save the city from a wave of drought-augmented superfires; equipped with keyboards and effects pedals, wearing trucker hats and plaid, these heroes of the drone wander forth to face the inferno, extinguishing flames with lush carpets of anoxic sound.

(Spotted via New York Magazine).