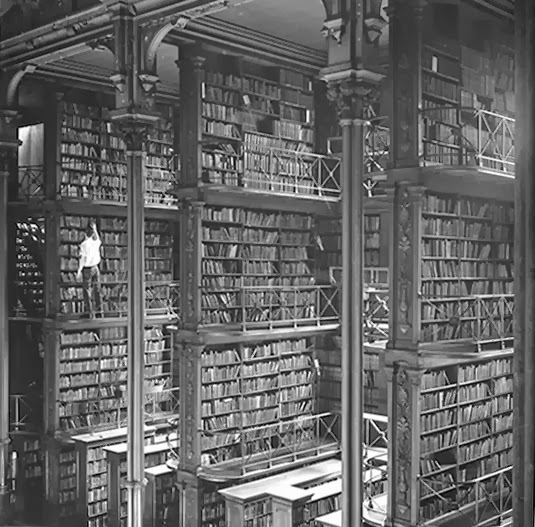

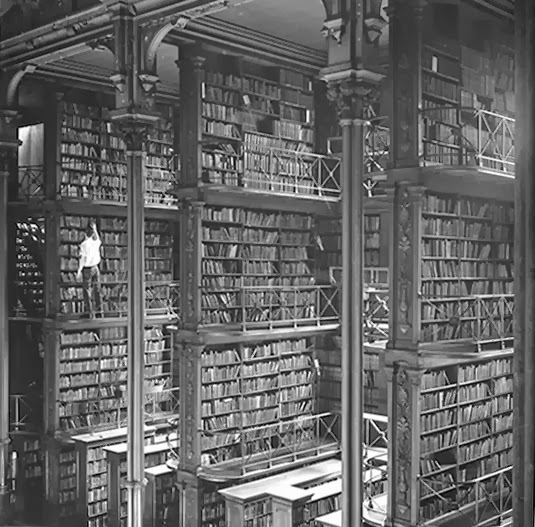

[Image: Cincinnati Public Library, 1870s; photo via Steve Silberman].

[Image: Cincinnati Public Library, 1870s; photo via Steve Silberman].

It’s that time of the year again, to take a look at the many, many books that have passed through the halls of BLDGBLOG the past season or two, ranging, as usual, from popular science to fiction, landscape history to the urban future of the refugee camp.

There are some great books included in this round-up, ones I’d love to help find a wider audience—however, as will be clear from a handful of descriptions below, and as is always the case with book round-ups here on BLDGBLOG, I have not read every book included in the following list and not all of them are necessarily new.

However, in all cases, these books are included for the interest of their approach or for their general subject matter, and the wide range of themes present should give anyone at least a few interesting titles to seek out for autumn reading.

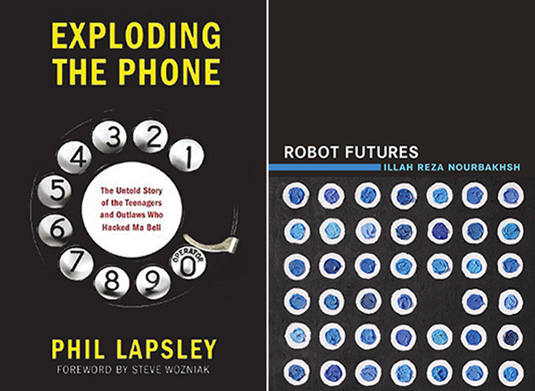

1) Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell by Phil Lapsley (Grove Press)

One of the most enjoyable books of my summer was Exploding the Phone by Phil Lapsley. Lapsley’s history of “phone phreaks,” or people who successfully hacked the early phone networks into giving them free calls to one another and around the world, would read, in a different context, like some strange occult thriller featuring disaffected teenagers tapping into a supernatural world. Weird boxes, unexplained dial tones, and disembodied voices at the end of the line pop up throughout the book, as do surprise cameos from a pre-Apple Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs.

Teenagers throwing frequencies and sounds at vast machines through telephone handsets managed to unlock another dimension of the phone network, Lapsley explains, a byzantine geography of remote switching centers and international operators. In the process, they helped pave the way for the hackers we know today. I have heard, anecdotally, from a few people who were around and part of these groups at the time, that Lapsley got some of his details wrong, but that didn’t take away from my enjoyment of—or inability to put down—his book. Recommended, and very fun.

2) Robot Futures by Illah Reza Nourbakhsh (MIT Press)

This pamphlet-length book by Carnegie Mellon University’s Illah Reza Nourbakhsh on the future of robotics pays admirable attention to the fundamental problem of even defining what “robotics” is. Better yet, Nourbakhsh prefaces each of his short chapters with fictional interludes exploring speculative scenarios of future robotics gone awry. There is a disturbing vignette in which flying robot toys programmed to recognize human eye contact swarm around and terrify anyone not hiding their gaze behind wearing sunglasses—something the toys’ manufacturer never predicted—as well as a memorable scenario in which new forms of robot-readable graffiti throw entire self-driving traffic systems into a tizzy, making car after car wrongly report that an impenetrable roadblock lies ahead. Call it traffic-hacking.

In the end, Nourbakhsh suggests, robots will prove to be fundamentally different from human beings, and we should be prepared for his. “A robot moving down the street will see in all directions, not simply in front of it like humans,” he writes. “If that robot is connected to a network of video cameras along the street, it will see everywhere on the street, from all angles, the entire time it walks. Imagine this scenario. A not-very-clever robot walking down the street will have access to entire synthesized views of the street—up and down, behind you, down the alley, around the corner—and be able to scroll back through time with perfect fidelity. As you approach this robot, it might be cognitively much dumber than you, but it knows far more about its surroundings than you do. It stops suddenly. What do you do? There is no common ground established between you and this robot, just the fact that you occupy the same sidewalk.”

3) Beyond The Blue Horizon: How The Earliest Mariners Unlocked The Secrets Of The Oceans by Brian Fagan (Bloomsbury Press)

Brian Fagan, an environmental historian known for his books on climate change and civilization, has written a great example of what might be called adventure-history. Beyond the Blue Horizon takes us through roughly twenty thousand—even potentially, depending on how you interpret the archaeological evidence, more than one hundred thousand—years of human seafaring. Every few pages, amidst tales of people sailing in small groups, even drifting, seemingly lost, for days at a time across vast expanses of open water, Fagan makes arresting observations, such as the fact that early Pacific navigators, laden down with seeds and plants, “literally carried their own landscape with them,” he writes.

The importance of the coast in supporting human settlement, and the absolute centrality of the sea—rather than continental interiors—in shaping human history, gives Fagan multiple opportunities to refocus our sense of our own remote past. We are not landed creatures of roads and automobiles, Fagan argues, but a maritime species whose entire childhood and adolescence was spent paddling past unknown coastlines, searching for freshwater rivers and streams—a “world of ceaseless movement,” as he calls it, including now lost islands, deltas, and coasts. Fagan’s brilliance at describing landscapes as they undergo both seasonal changes and variations in climate also applies to his depictions of Earthly geography when sea levels were, for most of the eras described in his book, more than 300 feet lower than it is today. It was another planet—a maritime world—one that humans seem to have lost sight of and forgotten.

4) The Human Shore: Seacoasts in History by John R. Gillis (University of Chicago Press)

John R. Gillis’s look at “seacoasts in history” proves to be compulsively readable, sustaining many long subway rides for me here in New York, although the final few chapters fall off into unnecessarily long quotations from what seems like any random academic source he could find that mentioned the sea. This is too bad, because a shorter, more tightly edited version of this book would be a dream. Gillis is not shy about making outsized claims for revising the history of human civilization. The shore is “the true home of humankind,” he writes, “the original Eden.” He wants Westerners to forget the “terracentric history” they’ve been taught, which is, he points out, simply a historical misunderstanding of where humans actually spent 95%—the number Gillis uses—of their development: on shorelines and coastal islands.

“The book of Genesis would have us believe that our beginnings were wholly landlocked,” he writes, “but it was written at the time that the Hebrews were settling down to an agrarian existence.” Gillis quotes the words of writer Steve Mentz here, who argued that we need “fewer gardens, and more shipwrecks” in our narrative understanding of human prehistory.

Gillis allows his book some intriguing political subthemes. He writes, for example, that “it would be a very long time, almost three hundred years, before Europeans realized the full extent of the Americas’ continental character and grasped the fact that they might have to abandon the ways of seaborne empires for those of territorial states.” He adds, “for the first century or more [of their habitation in the Americas], northern Europeans showed more interest in navigational rights to certain waterways and sea tenures than in territorial possession as such.” Rivers and lakes were the key to ruling North America, for a time; and, seemingly since the interior land rush of U.S. history, the “seaborne” ways of humans, with or without a state to back them, have been forgotten.

As a brief side note, it’s interesting here to look at the Somali pirates so often mythologized in Western media, including the forthcoming Paul Greengrass film Captain Phillips—that stateless, seaborne groups of humans still exist and are the rogue scourge of landed empires (see also The Enemy of All by Daniel Heller-Roazan, etc.).

5) The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush by Davig Igler (Oxford University Press)

David Igler’s own book on all things anthropologically oceanic focuses solely on the Pacific Ocean, from the first wave of European exploration to early-modern sea trade. Igler, too, finds the land-locked nature of traditional history both claustrophobic and incorrect. “The ‘places’ usually subjected to historical analysis—nations, regions, and localities—have fixed borders enclosing land and thus constitute terrestrial history,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “Historians have far less experience imagining the ways that oceanic space connects people and polities, rather than separating them.” Igler’s larger point—that tides, currents, and winds, even specific ships, are also, in a sense, “places” deserving of historical recognition—animates the rest of the book.

Mankind Beyond Earth: The History, Science, And Future Of Human Space Exploration by Claude A. Piantadosi (Columbia University Press)

6) This book is admittedly quite hampered by its extraordinary practicality: there is very little poetry here, mostly straight talk of musculoskeletal disorders in low gravity and heat-loss from warm bodies in space. We begin on the ground floor, not only with a short and perhaps unnecessary history of the U.S. space program, but with the very basics of human physiology and the mechanics of flight. I suspect, however, that most readers are perfectly willing to jump into the deep end and read what’s on offer in the book’s later chapters: human visits to Mars, to asteroids, to “big planets, dwarf planets, and small bodies,” in Piantadosi’s words, to the “moons of the ice giants” and beyond. Ultimately, though, the book is simply too dry to feel like these later glimpses of “mankind beyond Earth,” as the title teasingly—and, for the most part, misleadingly—promises, are a worthy reward. If you must, one to look for in the local library.

7) Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction by Annalee Newitz (Doubleday)

Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of io9 and thus, now, a colleague of mine, has exceeded all expectations with the research, depth, and range of this quirkily enthusiastic look at planetary mass extinction. Her early chapters on dinosaurs, plagues, extremophiles, world-altering volcanic eruptions, long geological eras when the Earth was locked in ice, possible human/Neanderthal guerrilla warfare (not to mention inter-breeding), and much more, are like a New Scientist article you hope never ends. It’s an exciting read.

Oddly, though, the central premise of the book—that, through urbanization, human beings will find ways to avoid their own extinction—feels tacked on and unconvincingly developed. If I’m being honest, it feels like Newitz is trying to make more of an ideological point about the political value and cultural centrality of cities today, rather than actually arguing rationally for the possibility that cities will save the human species. This is especially the case if we’re talking about—as, in this book, we are—catastrophic asteroid impacts or the outbreak of a super-virus. This otherwise gripping book thus has a bit of an are-you-serious? feel as it wraps up its final fifty pages or so. While advancing a theory of safety achieved through collective living, urban farming, and social cooperation, Newitz also inadvertently seems to contradict the first command of her book’s title: to scatter. That is, to fling ourselves to the far edges of the universe—to explore, survive, and mutate with the cosmos—not to band together, urbanize, and cooperate.

As such, it seems possible to imagine an identical version of this book—identical, that is, for 200 pages or so—but with a radically differnet ending: one in which truly scattering, adapting ourselves, isolating ourselves, and differentiating our civilizational pursuits—even differentiating our very DNA through evolution in separation—would be the most effective way to avoid human extinction. But that argument, it seems, is ideologically impermissible; it makes you an anti-state survivalist, a cosmic redneck, building bunkers in the Utah desert or on the moons of another world, more Ted Nugent than Stewart Brand.

In any case, putting political arguments like these aside, the book ends with a mind-popper of a quotation. In a conversation with Randii Wessen at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, Wessen tells Newitz: “Our kids are the last generation who will see no city lights on the Moon.” This is both wonderful and terrible, and as concise a statement as I’ve read anywhere to show the human future rolling on.

8) Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars by Lee Billings (Current)

Gifted science writer Lee Billings takes us on a search for other Earths—or, more accurately, for habitable “exoplanets” where life like us may or may not have a chance of existing. The book starts off with quite a coup. Billings treats us to a long, at-home visit with astronomer Frank Drake of Drake’s Equation fame: the abstract but reasonable calculation used for decades now to determine whether or not intelligent civilizations might exist elsewhere (and, by extension, how likely it is that humans will find them).

The book is not hard science, it is easy to follow, and Billings is a great writer; his tendency, however, veers toward the humanistic, following the life stories of individual astronomers or physicists here on Earth as they search the outer reaches of the detectable universe for signs of exoplanets.

A sizable diversion late in the book, for example, takes us on a canoe trip far into the Canadian north, past lakes and rivers, with a wary eye on approaching storms, to tell the story of how physicist Sara Seager met and fell in love with one of her colleagues. It is not a short diversion, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that Seager’s canoe trip has little to do with the search for “life among the stars,” as the book’s subtitle suggests. It is at moments like this, as Seager and her partner paddle from one portage to another, that I found myself wondering if the only stories to tell are of other human beings—whether scientists or NASA administrators—then why, in a sense, are we looking for exoplanets at all?

Of course, the book jacket never promised us surreal descriptions of other worlds. But it’s hard not to hope for exactly that: that Billings would focus his considerable rhetorical powers away from our world for a few more chapters and offer those evocative glimpses of Earth-like planets I suspect so many readers will come to his book to find—visions of worlds like ours but magically, cosmically different—and thus communicate the beautiful, poetically irresistible urge to discover them. His introductory descriptions of the formation of our solar system, for instance, are breathtaking, clear, and poetic, and similar passages elsewhere show the pull of the exoplanetary; the narrative structure of the scientist profile seems inadvertently to have focused the bulk of the book’s attention here on Earth, where we are already bound, rather than to let the strange light of the universe shine through more frequently.

But this is like complaining about dessert after a delicious meal. I’ll simply hope that Billings’s next book concentrates more on the inhuman allure so peculiar to astronomy, a field astonishingly rich with worlds mortal humans long to see.

9) Are We Being Watched?: The Search for Life in the Cosmos by Paul Murdin (Thames & Hudson)

The off-putting and sensationalistic title of Paul Murdin’s new book is, thankfully, not a sign of things to come in the text itself. Murdin’s sober yet thrilling look at the history and future of astrobiology is a bright spot in a recent spate of books about the possibility of extraterrestrial life. “The twenty-first century is the century of astrobiology,” he writes in the first sentence of chapter one; indeed, he adds with extraordinary confidence, “this is the era in which we will discover life on other worlds, and learn from it.”

Amidst many interesting tidbits, one worth repeating here actually comes from Murdin’s quotation of paleontologist Simon Conway-Morris. Conway-Morris, referring to the possibility of discovering truly alien life, rightly suggests that we could very well have no idea what we’re looking at. Indeed, he memorably says, these other life forms could be “constructions so unfamiliar that they are only brought home by accident and then inadvertently handed over for curation in a department of mineralogy.” The idea that rocks sitting quietly in a Natural History museum somewhere are actually alien life forms is mind-blowing and but one take-away from this thought-provoking book.

Over the course of Are We Being Watched?, Murdin enjoyably goes all over the place, from amino acids to plate tectonics, to radio-stimulated organic molecules in the atmosphere of Titan. As if channeling H.P. Lovecraft, Murdin at one point writes that, on Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa, scientists have seen the same churning processes as witnessed in Antarctica, but, on Europa, “we see the results of this churning as colored stains on ridges of ice at the boundaries of ice floes. Perhaps in these colored stains lie dead creatures, brought up from the depths of the ocean and exposed to view by orbiting spacecraft or landers that can rove over the surface.”

10) Frankenstein’s Cat: Cuddling Up to Biotech’s Brave New Beasts by Emily Anthes (FSG)

Frankenstein’s Cat follows the 21st-century quest to re-engineer biology, to design “the fauna of the future,” as the book promises, or “biotech’s brave new beasts,” where resurrected species, pets with prostheses, and militarized insects crawl through forests of genetically modified trees. At once terrifying and thrilling, and animated in all cases by the gonzo enthusiasm of any science operating at seemingly unstoppable speed, Emily Anthes’s book shows the weird biological breakthroughs that will ultimately create the landscapes of tomorrow: the cities, gardens, parks, oceans, and backyards our descendants will inevitably mistake for nature (and then, eventually, dismiss as mundane).

11) Sweet & Salt: Water And The Dutch by Tracy Metz and Maartje van den Heuvel (NAi Publishers)

Journalist Tracy Metz and art historian Maartje van den Heuvel have teamed up for this collaborative look at “environmental planning” in the Netherlands, with a focus on all things aquatic. While Metz visits the country’s numerous megaprojects and anti-flooding infrastructure to speak with water engineers, “dike wardens,” and other stewards of Holland’s relationship with rain and the sea, van den Heuvel assembles a spectacular catalog featuring visual depictions of waterworks throughout Dutch art history. This is “the visualization of water in art,” as she calls it, revealing “anxieties about flooding” and a deep-rooted infrastructural patriotism inspired by the technical means for controlling that flooding.

Ultimately, the book’s goal is to show how Dutch water management is changing in the face of rising sea levels and climate change, and how “water is coming back into the city,” as Metz writes, changing the nature of contemporary urban design.

12) Dutch New Worlds: Scenarios in Physical Planning and Design in the Netherlands, 1970-2000 by Christian Salewski (010 Publishers)

This well-illustrated history and catalog of large-scale hydrological projects in the Netherlands—and the “Dutch new worlds” those projects helped generate—offers a provocative look at the very idea of infrastructure. Salewski suggests that a nation’s infrastructure is like literature or mythology, a built narrative in which a much larger constellation of dreams and aspirations can be read. “There is no Dutch Hollywood,” Salewski writes, “no cinematic dream machine that constantly processes the current view of the future into easily digestible, mass-consumed science fiction movies. Dutch views into the future are probably best found not in cultural works of literature and art, but in physical planning designs.” That is, in the dams, dikes, levees, and polders the rest of the book goes on to so interestingly describe. Infrastructure, Salewski offers, is one of many ways in which a nation dreams.

13) Bird On Fire: Lessons From The World’s Least Sustainable City by Andrew Ross (Oxford University Press)

Andrew Ross takes a critical look at Phoenix, Arizona, a desert city “sprawling over a thousand square miles, with a population of four and a half million, minimal rainfall, scorching heat, and an insatiable appetite for unrestrained growth and unrestricted property rights.” As the city tries to “green” itself through boosts in public transportation and a more sensible water management strategy—among other things—Ross asks if an urban transformation, something that might save Phoenix from its current parched fate, is even possible.

14) Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters by Kate Brown (Oxford University Press)

Kate Brown’s Plutopia creates a horrifying set of conjoined urban twins, so to speak, by both comparing and contrasting the purpose-built plutonium production towns of Richland, Washington, and Ozersk, Russia. These were fully planned and state-supported facilities, yet both were also highly delicate, secret cities—in Ozersk’s case, literally off the map—constantly at risk of nuclear disaster. And disaster, of course, eventually comes.

Brown points out how, between the two of them, Richland and Ozersk released four times the amount of radiation into the environment as the meltdown at Chernobyl, and she tracks the disturbing long-term health and environmental effects in the surrounding regions. In both cases, perhaps cynically, perhaps inspiringly, these polluted regions have become nature reserves.

In a particularly troubling anecdote from the final chapter, referring to the experience of Richland, Brown points out that “periodically deer and rabbits wander from the preserve and leave radioactive droppings on Richland’s lawns,” but also, more seriously, that multiple wineries have sprung up perilously close to the hazard zone, “near the mothballed plutonium plant.” While sipping wine at one of those very vineyards, Brown tries to talk to the locals about the potential for radiation in the soil—and, thus, in the wine—but, unsurprisingly, they react to her questions “testily.”

These carefully manicured utopian towns, like scenes from The Truman Show crossed with Silkwood, with their dark role in the state production of plutonium, give us the “Plutopia” of the book’s title. Ozersk and Richland are “citadels of plutonium,” she writes, instant cities of the atomic age.

15) From Camp To City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara by Manuel Herz (Lars Müller Publishers)

Based on original research from a studio taught at the ETH in Zurich, architect Manuel Herz has assembled this fascinating and important guide to the urban and quasi-urban structures of refugee camps. Focusing specifically on camps in extreme southwest Algeria, populated by people fleeing from conflict in the Western Sahara, these camps are, Herz suggests, Western instant urbanism stripped bare, the city shown at its factory presets, revealing the infrastructural defaults and basic political conditions of the modern metropolis. They are “the spatial manifestation of the state of exception,” he writes, citing Giorgio Agamben, mere “holding areas” in which urban forms slowly take shape and crystallize. The camps are where, Herz writes, “Architecture and planning becomes [sic] a replacement for a political solution.”

From the architecture of the tents themselves to the delivery infrastructures that bring water, food, and other vital goods to their inhabitants, to culturally specific spatial accouterments, like carpets and curtains, Herz shows how the camps manage to become cities almost in spite of themselves, and how these cities then offer something like training grounds for future nations to come. In Herz’s own words, “the camps act also as a training phase, during which the Sahrawi society [of the Western Sahara] can develop ideas and concepts of what system of education they want to establish, and learn about public health and medical service provision. The camps become a space where nation-building can be learned and performed, to be later transferred to their original homeland, if it becomes available in the future.”

This idea of the state-in-waiting—and its ongoing spatial rehearsal in the form of emergency camps—runs throughout the book, which is also a detailed, full-color catalog of almost every conceivable spatial detail of life in these refugee camps. In the process, Herz and his team have assembled a highly readable and deeply fascinating look at urbanism in its most exposed or raw condition. “In the blazing sun of the Sahara Desert,” he concludes, “we can observe the birth of the urban condition with a clarity and crispness almost unlike anywhere else in the world.”

16) Roman Disasters by Jerry Toner (Polity)

Cambridge Classicist Jerry Toner had described his wide range of interests as being centered on the notion of “history from below.” He has written prolifically about ancient Rome, in particular, from several unexpected points of view, including popular culture in antiquity, the smellscape of early Christianity, and an currently in-progress work on crime in the ancient metropolis.

Roman Disasters looks specifically at imperial disaster-response, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, catastrophic fires, warfare, and disease. Toner describes how the abstract notion of risk was first formulated and understood; the role of religious prophecy in “imagining future disaster”; and halting, ultimately unsuccessful attempts to construct a fireproof metropolis, such as the widening of city streets and the creation of a semi-permanent Roman fire brigade.

Very much a history, rather than a page-turner directed at a popular audience, Roman Disasters nonetheless offers a compelling and unexpected look at the ancient world, one peppered with refugee camps, tent cities, and displaced populations all looking for—and not necessarily finding—imperial beneficence.

17) Picking Up: On the Streets and Behind the Trucks with the Sanitation Workers of New York City by Robin Nagle (FSG)

Robin Nagle is an “anthropologist-in-residence” at the NYC Department Sanitation. Picking Up is her document of that incredible—and strange—backstage pass to the afterlife of the city, where all that we discard or undervalue simply gets tossed to the curb. Nagle tags along with, interviews, and reveals the “garbage faeries” who rid our streets of the unwanted detritus of everyday life, whether trash or snow. In the process, she’s written a kind of narrative map or oral history of another New York, one with its own flows and infrastructure, and one that exists all but invisibly alongside the one we inhabit everyday.

18) Factory Towns of South China: An Illustrated Guidebook edited by Stefan Al (Hong Kong University Press)

Architect Stefan Al, currently teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, leads a team of researchers to the Pearl River Delta, the “factory of the world,” to explore how people live and—even more—how they work in the region. A fascinating glimpse at the “self-contained world” of what amounts to corporate-industrial urbanism, the book nonetheless feels very much like a book assembled by architects who had a grant for producing a publication: it is heavy on comparative infographics, layered images, pie charts, and small-print introductory essays, all on coated paper resistant to underlining. The subject matter is fascinating, but the book is ultimately of less use than, say, sending Robin Nagle to visit these “factory towns of south China,” reporting back about the complicated lives and material cultures found there.

19) Ruin Nation: Destruction And The American Civil War by Megan Kate Nelson (University of Georgia Press)

Megan Kate Nelson’s Ruin Nation is a kind of Piranesian guide to the Civil War ruins of American cities of the 19th century. The book is a bit slow and overly cautious in its descriptions, but it is remarkable for a specific focus on architectural ruins following the Civil War. “Architectural ruins—cities and houses—dominated the stories that soldiers and civilians told about the Civil War,” she writes in the book’s introduction, a time when whole cities were reduced to “lone chimneys” amidst the smoke and obliteration of urban warfare. We often hear—especially post-9/11—that Americans have never really experienced war and destruction on their own soil, but Nelson’s book convincingly and devastatingly shows how inaccurate a statement that is.

20) Line In The Sand: A History Of The U.S.-Mexico Border by Rachel St. John (Princeton University Press)

Heading west from the Gulf Coast, the U.S.-Mexico border takes an unexpected turn when you get past El Paso, Texas—that is, by not really turning at all. The border instead becomes a series of abnormally, mathematically straight lines, cutting, with only a few diversions north and south, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. It thus no longer follows any natural feature, such as the Rio Grande River.

But why is the border exactly here, and why the rigid, linear path that it takes? Rachel St. John’s “history of the western U.S.-Mexico border” looks at sovereignty, surveying, geography, diplomacy, war, conquest, and private property to piece together the tangled story of this “line in the sand” and the people (and economies) it has divided. Line in the Sand—which often has the ungainly feel of a Ph.D. thesis later edited into a book—ends with a critical look at the “operational security” falsely promised by a border fence, and a more hopeful look at mutations of the border region yet to come.

21) The Earthquake Observers: Disaster Science From Lisbon To Richter by Deborah R. Coen (University of Chicago Press)

Deborah Coen’s Earthquake Observers looks at the history of seismology—or the study of earthquakes—but, more specifically, seismology’s transition from something like a folk art of human observation to an instrumented science. It is a consistently interesting book, so much so that I invited Coen to speak to my class at Columbia last semester.

The book includes a great deal worth mentioning here, from the gender of early earthquake observers—writing, for example, specifically in reference to early-modern domesticity, that “a quiet, housebound lifestyle and close attention to the arrangement of domestic objects put many bourgeois women in an excellent position to detect tremors”—to the literally geopolitical effects of earthquakes. In the latter case, a state of emergency following catastrophic seismic events helped to influence 20th-century legal theory as well as to challenge accepted hierarchies of what it means for a state to respond. “Particularly in the Balkans,” she writes, “earthquakes called into question the political framework that tied the monarchy’s fringes to its two capitals: which level of the state’s intricate web of governance would respond?”

John Muir, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, and the study of earthquake-related traumas, or “seismopathology,” all make their appearance in Coen’s study of how seismology became both modern and scientific.

22) From Roof To Table: Photographs By Rob Stephenson by Rob Stephenson (Design Trust for Public Space)

This magazine-style pamphlet of images by photographer Rob Stephenson documents urban farming efforts—not necessarily limited to roofs—across New York City. Plots of land beside empty brick warehouses, backyards, and even university labs bloom with fruits and vegetables in Stephenson’s full-color shots. “With the influx of people to cities and a continuing rise in the financial and environmental costs of shipping food, the widespread and large-scale adoption of urban agriculture seems inevitable,” Stephenson writes in an accompanying project description. “New York City, with its network of backyard vegetable plots, community gardens and rooftop farms, is at the forefront of this transformation.”

23) The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome by Gordon Campbell (Oxford University Press)

Gordon Campbell’s history of the garden hermit attempts to discover why the phenomenon of the live-in hermit—an actual human being, installed in a landscaped garden, acting as a form of living ornament—arose at all. Along the way, he explores what architectural structures these hermits required and the cultural motifs their strange roles kicked off. “Who were these people?” Campbell asks. “Why did landowners think it appropriate to have them in their gardens? What function did they serve?”

24) Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla by David Killcullen (Oxford University Press)

Military strategist David Kilcullen takes on the urban future of war, arguing that armed conflict will occur more often, and with increasingly devastating effects, in cities. If the future is such that, in his words, “all aspects of human life—including, but not only, conflict, crime and violence—will be crowded, urban, networked and coastal,” then it only makes sense to attempt to make sense of this, both sociologically and from the perspective of the military.

Citing everything from Richard Norton’s revolutionary notion of the “feral city” to Mike Davis’s Planet of Slums—Davis, in fact, blurbs the book—Kilcullen has written a must-read for anyone unconvinced by the rosy take on cities and their triumphant future currently dominating the best-seller list.

25) Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces by Radley Balko (PublicAffairs)

Radley Blako’s libertarian take on the “militarization of America’s police forces” is more Rand Paul than ACLU, if you will, but it’s a worthy read for all sides of the political debate. It opens with the jarring rhetorical question, “Are cops constitutional?” And it goes on from there to discuss legal debates on federal power and the 3rd and 4th Amendments, a short history of military tactics creeping into the U.S. police arsenal following urban riots in Watts, the rise of reality TV shows seemingly encouraging police belligerence, the War on Drugs, the Occupy Movement, today’s all but ubiquitous Taser (and its abuse), no-knock raids, and more.

If you’re interested in cities, you should also be interested in how those cities are policed, and this is as interesting a place as any to start digging.

26) Manhunts: A Philosophical History by Grégoire Chamayou (Princeton University Press)

I picked up a copy of this book after an interesting, albeit brief, email exchange with L.A. Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, who described a shift from the high-speed chase (that is, a large amount of space covered at high speed) to the manhunt (or a limited space studied with incredible intensity).

I’ve written about Hawthorne’s observation at greater length in my own forthcoming book about crime and architecture, and, while researching that book, I thought Grégoire Chamayou’s Manhunts would be a helpful reference. It was not, if I’m being honest, but it is, nonetheless, a striking work on its own terms: a history of what it means to hunt human beings, from runaway slaves and “illegal aliens” to Jews in World War II. He calls this an “anthropology of the predator”—“a history and a philosophy of hunting powers and their technologies of capture”—wherein the prey subject to destruction is a banished or shunned human being, terrifyingly relegated to the status of animal.

27) Rogue Male by Geoffrey Household (New York Review of Books Classics)

This strange, quite short, and very readable novel, recently brought back into print by the New York Review of Books, tells the story of a British political agent who fails in his attempt to assassinate an unnamed German political leader (who is, clearly, Adolf Hitler). The man flees Germany for the comparative safety of England, only to be relentlessly—and, as it happens, successfully—hunted by German agents intent on revenge.

It both does and does not spoil the rest of the book to reveal that the hunted man literally goes to ground, terrestrializing himself by digging a burrow in the Earth and hiding out there amidst the mud, the exposed tree roots, the darkness, and his own waste, sleeping unwashed in a humiliating cave of his own making, his clothes rotten, his feet swollen by rain, living underground at the side of a small lane in Britain’s agrarian hinterland. When he is found—and he is found—what could descend into a Rambo-like scene of violence and retaliation instead offers something that is still violent but far stranger, as this nearly worldchanging political actor, a failed assassin who could have changed the 20th century, finds a way to escape his grotesque and feral state.

Have a good autumn, and enjoy the books.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

(Thanks to Dan Bergevin for my copy of Out of the Mountains).

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: GPS satellites, via

[Image: GPS satellites, via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: From

[Image: From

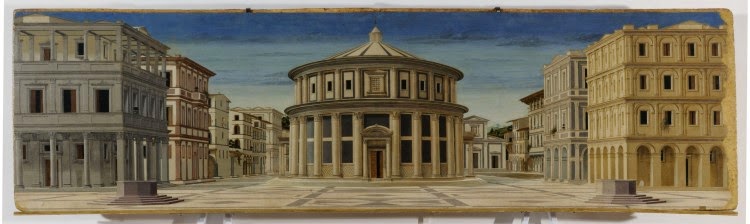

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: A perspectival representation of the “ideal city,” artist unknown]. [Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of

[Image: Jeff Bezos as perspectival historian. Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

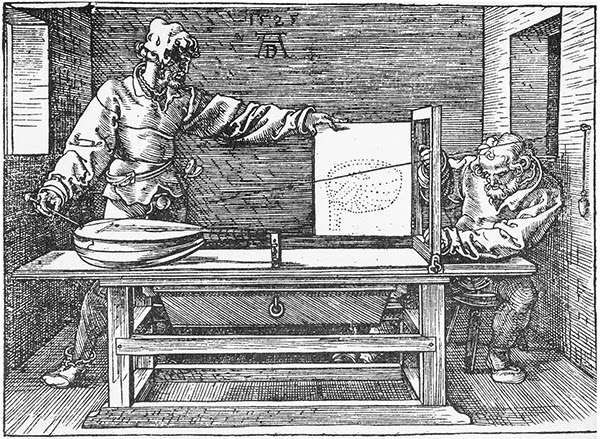

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer].

[Image: One of several perspectival objects—contraptions for producing spatially accurate drawings—by Albrecht Dürer]. [Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

[Image: Another “ideal city,” artist unknown].

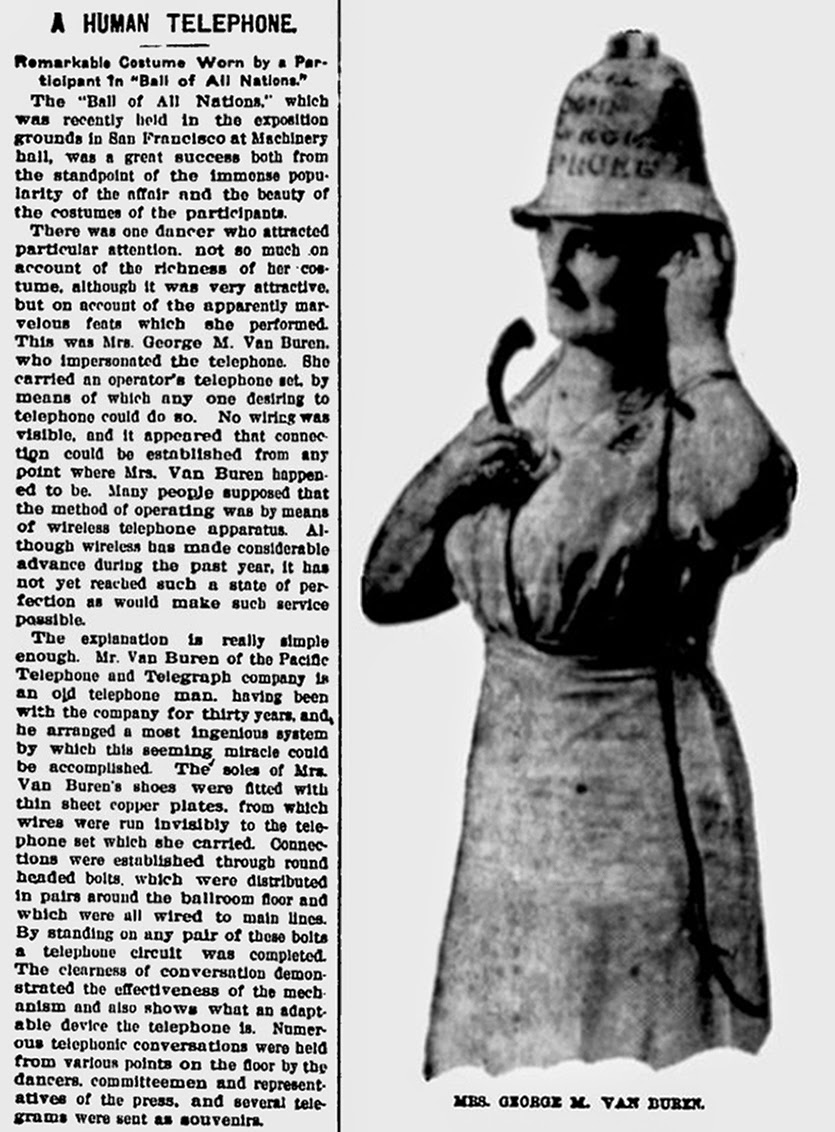

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914].

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914]. [Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via  [Image: Cincinnati Public Library, 1870s; photo via

[Image: Cincinnati Public Library, 1870s; photo via

[Image: Barbed wire, via

[Image: Barbed wire, via  [Image: From a June 1902 issue of

[Image: From a June 1902 issue of  [Image: The original fire house from

[Image: The original fire house from  [Image: 33 Thomas Street, via

[Image: 33 Thomas Street, via