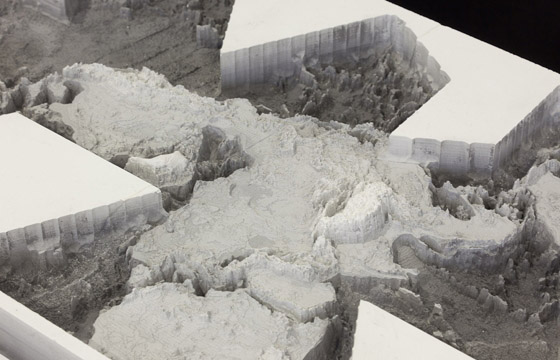

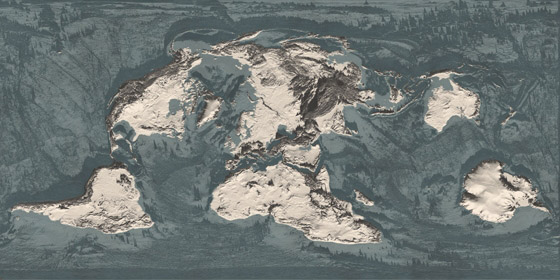

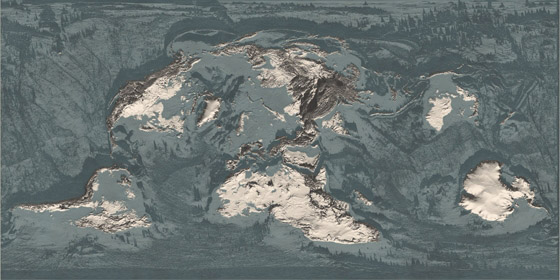

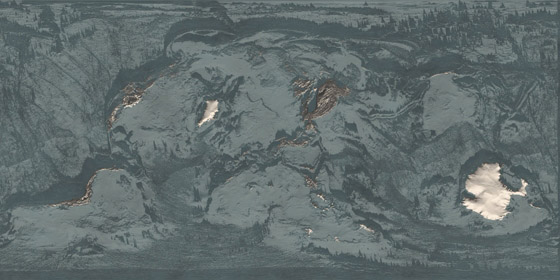

[Image: An only conceptually related photo from a volcano in Java, taken by Reuben Wu].

[Image: An only conceptually related photo from a volcano in Java, taken by Reuben Wu].

The invisibility of underground fires makes them particularly surreal and difficult to imagine: flames with no real room to flicker, moving slowly forward through the planet, relentlessly burning their way ever deeper into the landscape from below.

Whether that fire was caused by the ignition of a coal seam—as in Centralia or, my favorite example, in Australia’s Burning Mountain—or because subterranean strata of human-generated trash have caught fire, these events make for an especially spectral presence in the landscape. They remain entirely out of view except for the haze of their atmospheric effects, as they fill the air above with toxic gases.

This already strange phenomenon is hitting a whole new level of apocalyptic artificiality in a landfill outside St. Louis, Missouri. There, an underground fire is at risk of igniting old nuclear waste from U.S. weapons programs.

As the AP reports, “Beneath the surface of a St. Louis-area landfill lurk two things that should never meet: a slow-burning fire and a cache of Cold War-era nuclear waste, separated by no more than 1,200 feet.”

It’s worth pointing out that “the waste was illegally dumped in 1973 and includes material that dates back to the Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic bomb in the 1940s.” In many ways, then, this was an obvious problem just waiting to reassert itself.

An “emergency plan” has now kicked into gear to help fend off the potentially “catastrophic event” that would occur if these two things meet—the dormant deposit of nuclear waste and the respiring event of the underground fire.

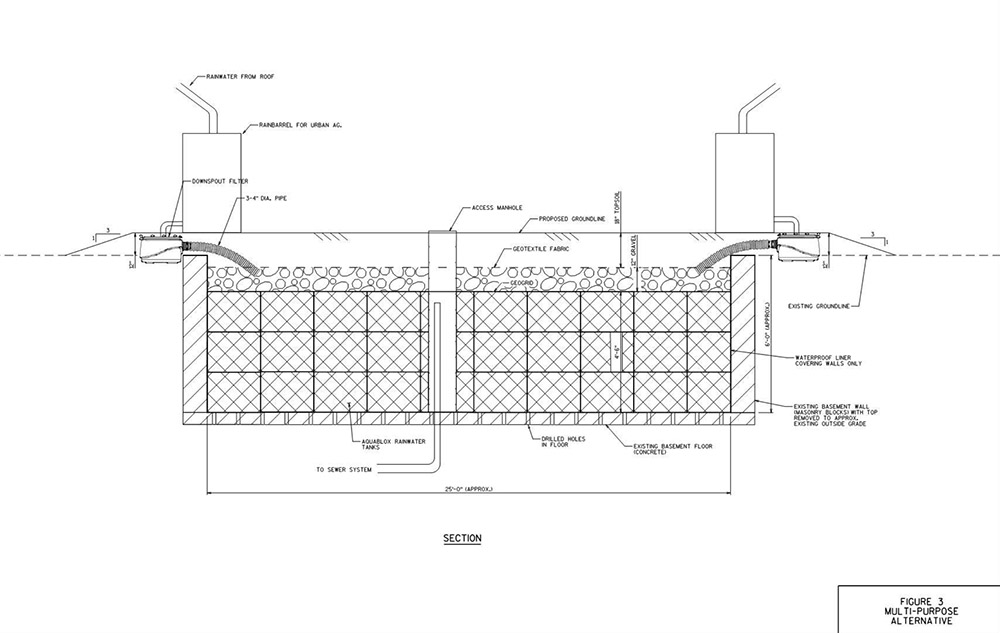

In effect, this plan is a massive undertaking of design: it is landscape architecture as a tool against crisis.

New structures called “interceptor wells” are being constructed, for example, to maintain a kind of thermal quarantine line between the fire and the nuclear waste—however, the fire already appears to have circumvented these buffers, at least according to the AP. For example, some safety reports from the site have allegedly “found radiological contamination in trees outside the landfill’s perimeter,” implying that the nuclear waste has already, in at least some capacity, entered the biosphere, and “another showed evidence that the fire has moved past two rows of interceptor wells and closer to the nuclear waste.”

Yet another report ominously claims that the management company in charge of the landfill simply “does not have this site under control.”

This slow-burning apocalypse brings to mind our earlier look at writer Robert Macfarlane’s recent work on the vocabulary we use for certain landscapes, how words come and go over time and how spatial atmospheres can be verbally communicated.

Is there a proper landscape term for a subterranean catastrophe ready to burst through the surface of the world and forever change things for the worse in its immediate vicinity?

(Thanks to Ben Brockert and Kevin Iris for the tip!)

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

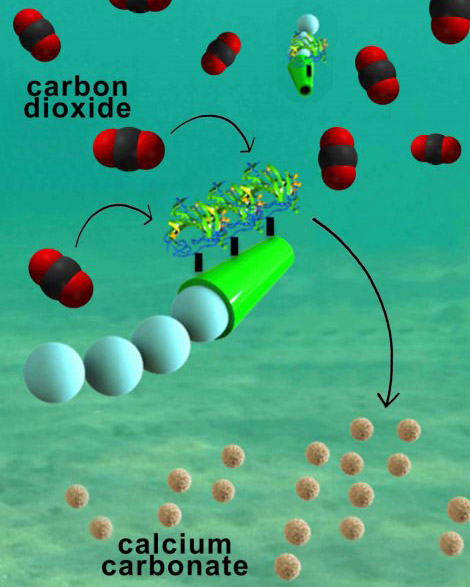

[Image: Micromotors at work, via

[Image: Micromotors at work, via  [Image: A Maltese limestone quarry, via

[Image: A Maltese limestone quarry, via

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photos by

[Image: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

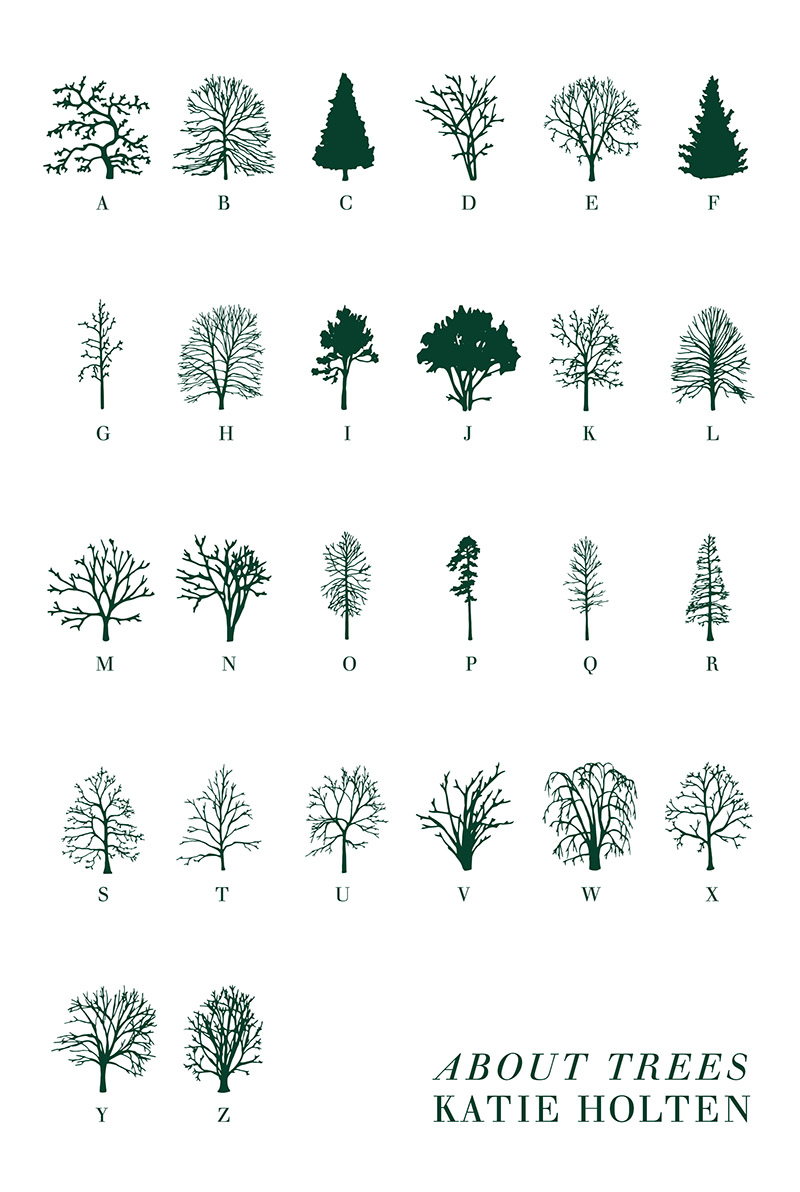

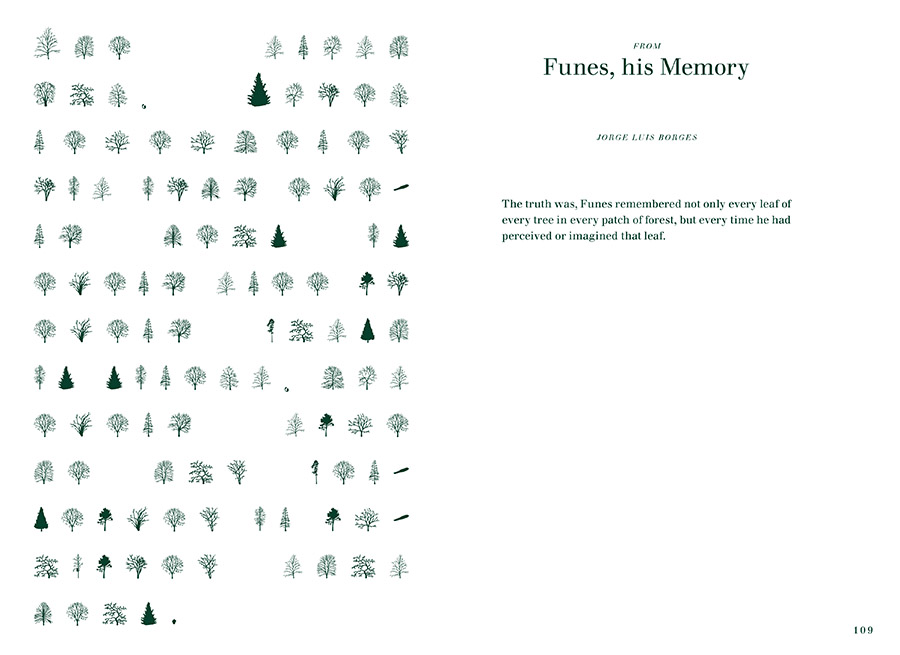

[Image: The cover for

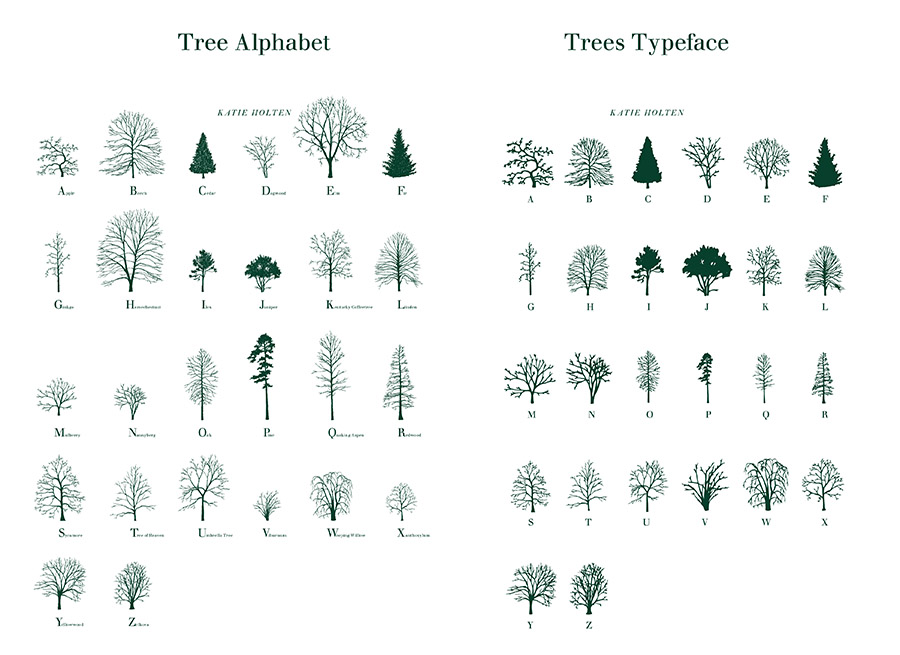

[Image: The cover for  [Image: The tree typeface from

[Image: The tree typeface from

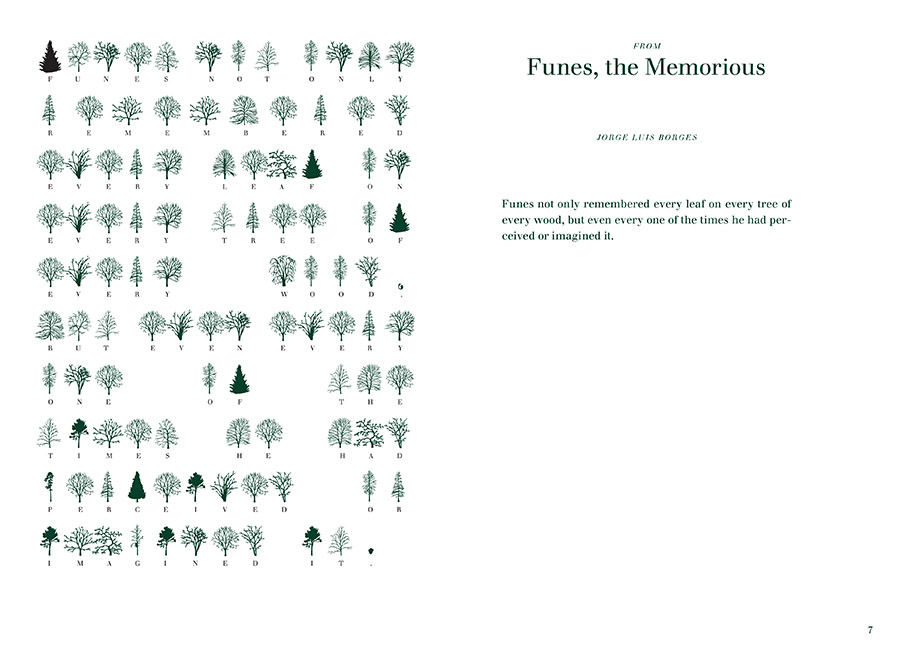

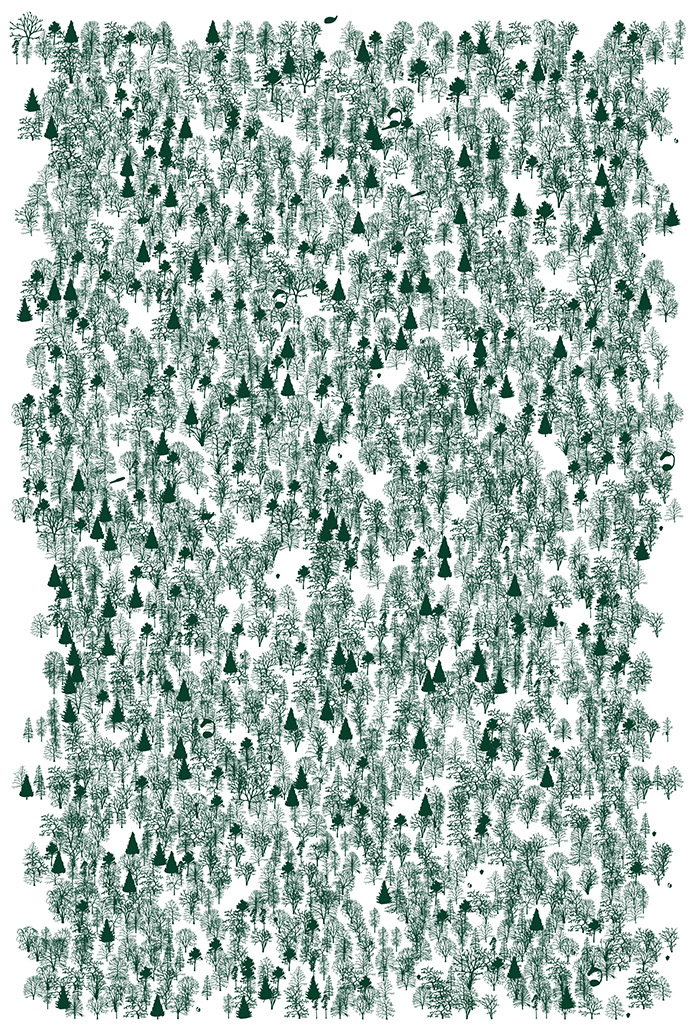

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from  [Image: From

[Image: From

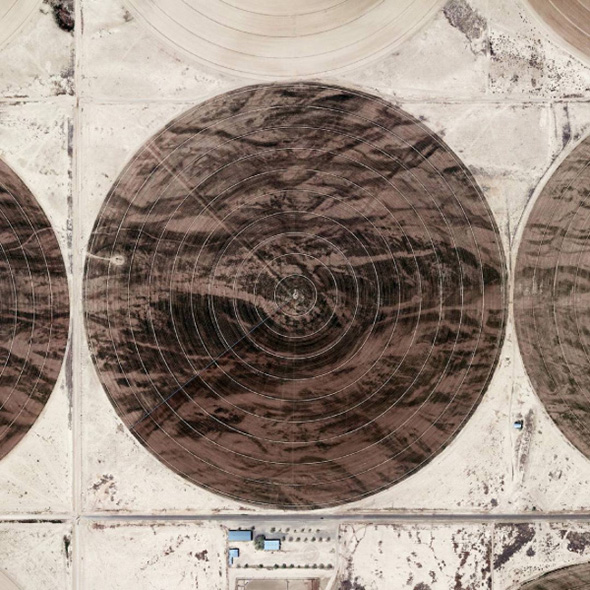

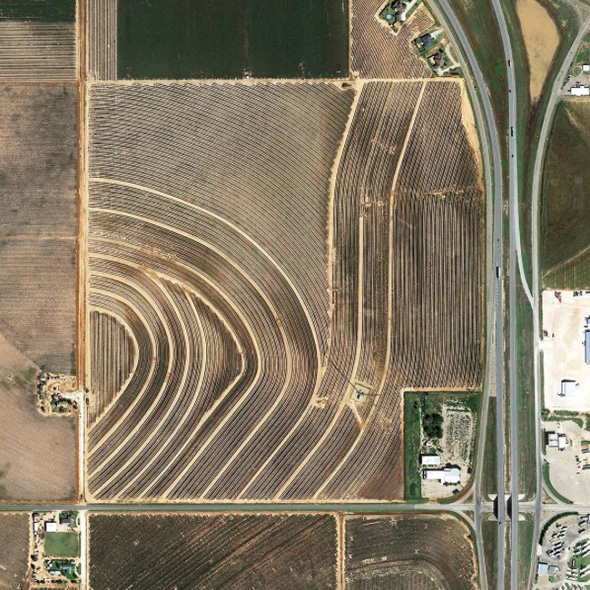

[Images: I’ve been enjoying a new Instagram feed called

[Images: I’ve been enjoying a new Instagram feed called

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Image: Snow-making equipment via

[Image: Snow-making equipment via  [Image: Snow-making equipment via

[Image: Snow-making equipment via  [Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via

[Image: Ski jumping in summer at Chicago’s Soldier Field (1954); via  [Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via

[Image: Making snow for It’s A Wonderful Life, via

[Image: Illustration by

[Image: Illustration by  [Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via

[Image: Hand-painted radiation sign at Chernobyl, via

[Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the