[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

I somewhat randomly found myself reading back through the irregularly updated blog of the British Museum earlier today when I learned about a project by Bristol-based artist Heidi Hinder called Financial Growth.

Financial Growth, Hinder explains in her guest post for the blog, is a still-ongoing “series of petri dish experiments.” It “reveals the bacteria present on coins and suggests that each time we make a cash transaction, we are exchanging more than just the monetary value and some tangible tokens. Hard currency could become a point of contagion.”

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

While Hinder develops this train of thought into a lengthy and provocative look at other means by which human beings could exchange microbes and bacteria for the purposes of financial interaction, I was actually unable to go much beyond than sheer awe at the basic premise of the project.

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

By culturing individual coins, Hinder has revealed a vibrant ecosystem of microscopic lifeforms thriving, garden-like, on every monetary token in our pockets; these are landscapes-in-waiting that we carry around with us every day.

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

[Image: From Financial Growth by Heidi Hinder; photo by Jonathan Rowley].

I was reminded of the famous shot of “the bacteria that grew when an 8-year-old boy who had been playing outside pressed his hand onto a large Petri dish,” posted to Microbe World last autumn.

[Image: Via Microbe World].

[Image: Via Microbe World].

We’re surrounded by the unexpected side-effects of these portable microbial communities.

We leave our traces everywhere—but we bear the traces of innumerable others, in turn, trafficking amongst microbiomes that are content to remain invisible until we force them to reveal themselves.

[Image: Via Microbe World].

[Image: Via Microbe World].

Think of artist Maria Thereza Alves’s project, Seeds of Change, for example, a “ballast seed garden” that explored the hidden landscapes unwittingly carried along by ships of European maritime trade, with seeds unceremoniously dumped as part of their ballast, often centuries old.

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

These were seeds left behind specifically from the ballast of ships—yet isn’t that exactly what Hinder’s project also explores, the portable, everyday ballast of bacteria left behind on our cash, our coins, our hands, our bodies?

After all, 94% of the money we handle every day has human feces on it. Put it in a petri dish and be wary of what begins to grow.

While Hinder’s larger point is that perhaps we could design a microbe-exchange economy based on the already-existing trade in bacteria we are all currently engaged in, whether we know it or not, the brute-force power of revelation makes Financial Growth grotesquely compelling.

We bring with us nearly infinite potential landscapes, carrying them in our wallets, purses, and pockets—on our hands, in the random waste left behind by ships and even airplanes—forming new, erratic ecosystems, a pop-up micro-wilderness we’re unable to control.

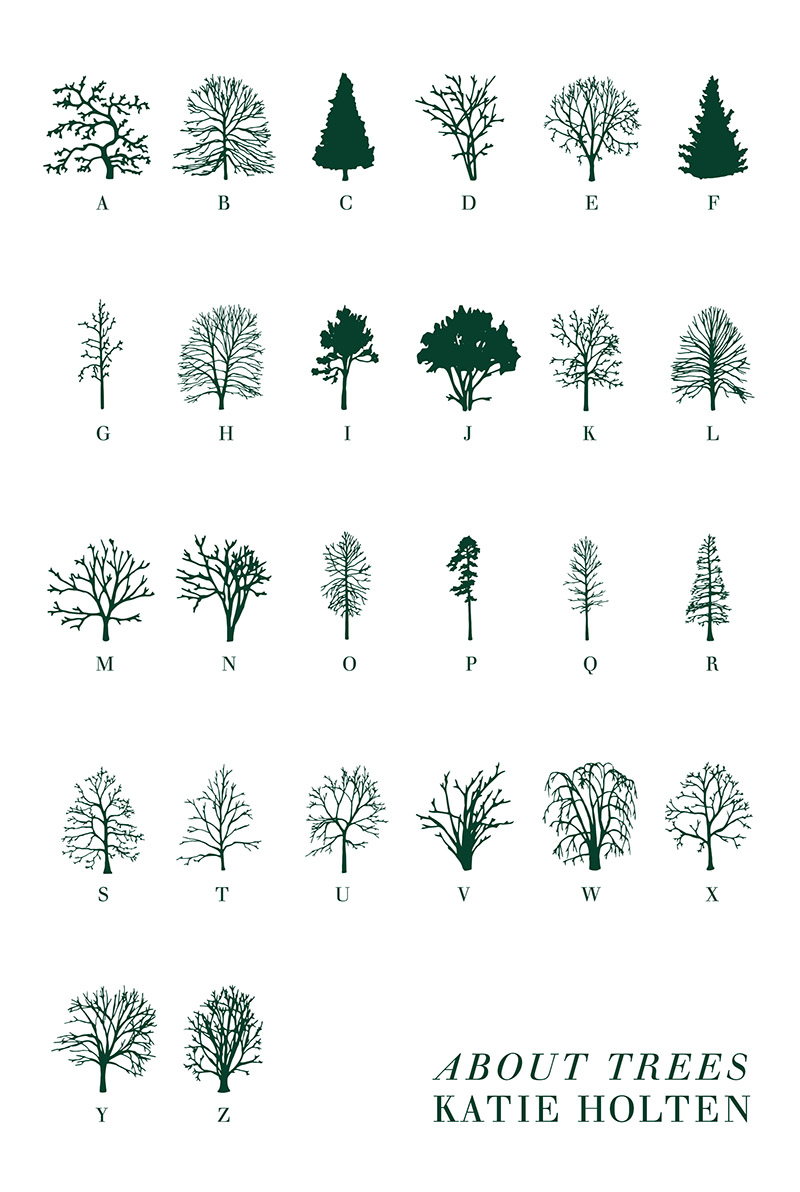

[Image: The cover for

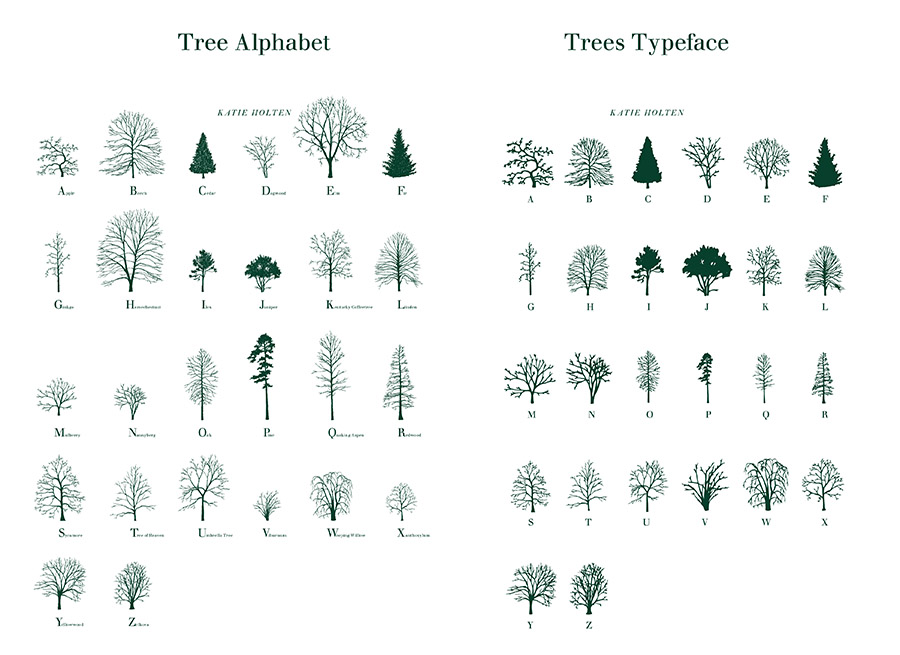

[Image: The cover for  [Image: The tree typeface from

[Image: The tree typeface from

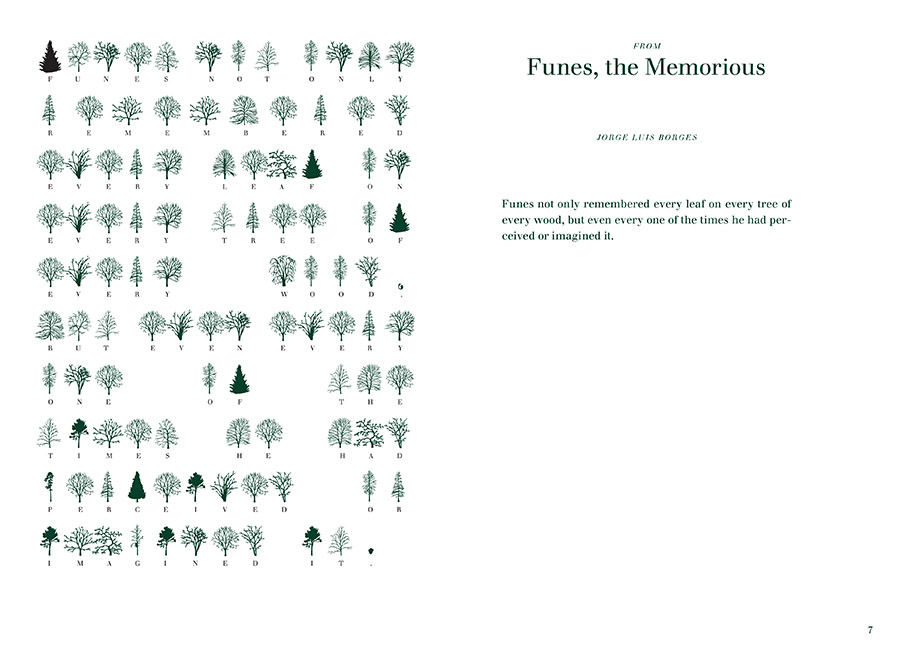

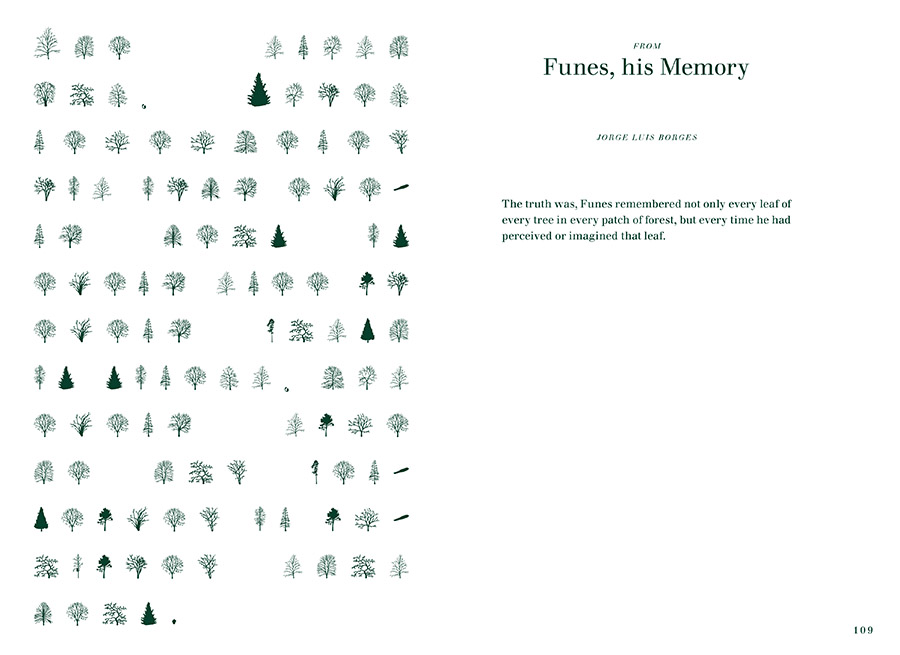

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: My own “crypto-forest of Utrecht,” via Google Maps].

[Image: My own “crypto-forest of Utrecht,” via Google Maps].