A few examples of landscapes waking up after long periods of time lying dormant have been in the news recently.

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

First, there is artist Maria Thereza Alves’s “ballast seed garden” project, called Seeds of Change, which arose from a moment of revelation:

Between 1680 and the early 1900s, ships’ ballast—earth, stones and gravel from trade boats from all over the world used to weigh down the vessel as it docked—was offloaded into the river at Bristol. This ballast contained the seeds of plants from wherever the ship had sailed. Maria Thereza Alves discovered that these ballast seeds can lie dormant for hundreds of years, but that, by excavating the river bed, it is possible to germinate and grow these seeds into flourishing plants.

While Alves seems not to have literally dug down into the old layers of the river in order to harvest her seeds—instead sourcing contemporary examples of species known to have sprouted from mounds of ballast over the last few hundred years—her project nonetheless has the character of a long-lost landscape waking up, popping up like a refugee amidst the rubble in a return to visibility.

[Images: The ballast garden, via Facebook].

[Images: The ballast garden, via Facebook].

This idea of accidental ballast gardens—heavily detoured landscapes-to-come lying patiently in wait before springing back to life several centuries after their initial transportation—is incredible; I might even suggest parallels here with such 21st-century problems as how we might sterilize spacecraft before sending them offworld, to places like Mars, lest we, in a sense, bring along our own bacterial “ballast” and thus unwittingly terraform those distant locations with escaped landscapes from Earth. Might we someday culture “ballast gardens” on other planets from the tiniest of remnant organic compounds found on our own ancient and dismantled ships?

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via Facebook].

Meanwhile, in a headline that reads like something straight out of Stanislaw Lem or H.P. Lovecraft, we read that “Nunavut’s Mysterious Ancient Life Could Return by 2100 as Arctic Warms.” In other words, forests that thrived in the hostile conditions of “Canada’s extreme north” nearly three million years ago might return to re-colonize the landscape as the region dramatically warms over the next century due to climate change.

This is a relatively mundane resurrection—after all, it is just a forest—but even the suggestion that future climate conditions on Earth might re-awaken ancient ecosystems, dormant environments in which humans might find it less than easy to survive, is an incredible cautionary tale for the future of the planet. That, and this story offers the awesomely mythic image of human explorers wandering across the thawing earth of the far north as strange and ancient things bloom from cracks in the ground around them.

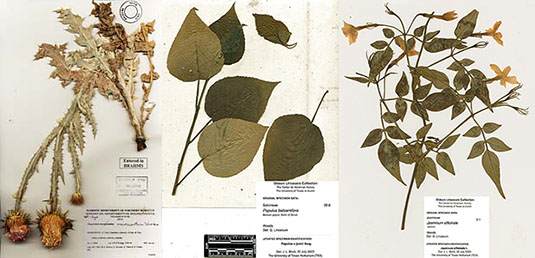

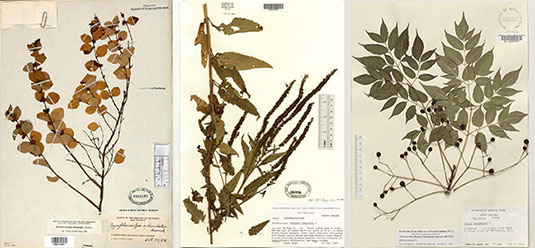

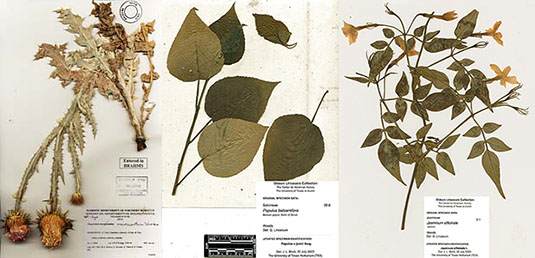

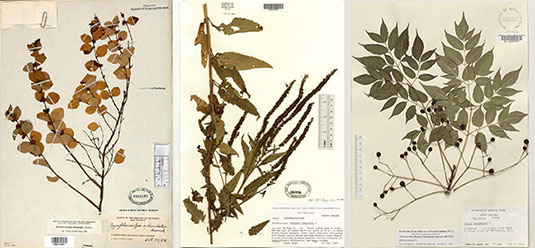

[Images: Various herbaria pages].

[Images: Various herbaria pages].

In both cases, I’m reminded of an essay published in Lapham’s Quarterly a few years ago, by novelist Daniel Mason. There, Mason writes about “nature’s return,” a scenario in which dormant and waylaid seeds thrive on the rubble of the present-day landscape. “In the dusty cracks between the concrete, seedlings would germinate, grow,” Mason writes, heralding unpredictable landscapes to come.

[Images: More herbaria pages].

[Images: More herbaria pages].

However, referring to these remnant seeds left over from older landscapes, Mason writes that “most would not germinate straight away,” even if given free rein over an empty field or cracked streetscape. “Rather,” he adds, these seeds “would lodge in microscopic nooks and crannies, some to be eaten or crushed, others to be paved over, but most, simply, to wait. A square meter of urban soil can contain tens of thousands of seeds persisting in a state of suspended animation, waiting to be woken from their slumber. After the fire brigades rescued the London Natural History Museum from German incendiaries, Albizia silk-tree seeds bloomed on their herbarium sheets, liberated from two hundred years of dormancy by the precise combination of flame and water.”

A square meter of urban soil can contain tens of thousands of seeds persisting in a state of suspended animation, waiting to be woken from their slumber. In Mason’s words, this return of dormant life “suggests the parallel existence of a hidden world, fully formed, simply awaiting the opportunity for expression.”

Whether dredging up old riverbeds full of ballast from previous centuries, or watching new storms form over the Arctic, bringing back climates unseen for millions of years, what might yet wake up from the ground around us, return from dormancy, resurrect, as it were, and make itself at home again on a planet that thought it had since moved on?

(Ballast garden link spotted via Katie Holten).

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via Wikimedia.]

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via Wikimedia.] [Image: From episode 9 of

[Image: From episode 9 of  [Image: From episode 9 of

[Image: From episode 9 of  [Image: From the “

[Image: From the “ [Image: Veduta dell’Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo (1776), by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; courtesy

[Image: Veduta dell’Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo (1776), by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; courtesy  [Image: An example of Periplaneta japonica, via

[Image: An example of Periplaneta japonica, via  [Image: Buddleia; photo by Steven Mulvey via the

[Image: Buddleia; photo by Steven Mulvey via the  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Images: The ballast garden, via

[Images: The ballast garden, via  [Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via  [Images: Various herbaria pages].

[Images: Various herbaria pages]. [Images: More herbaria pages].

[Images: More herbaria pages].