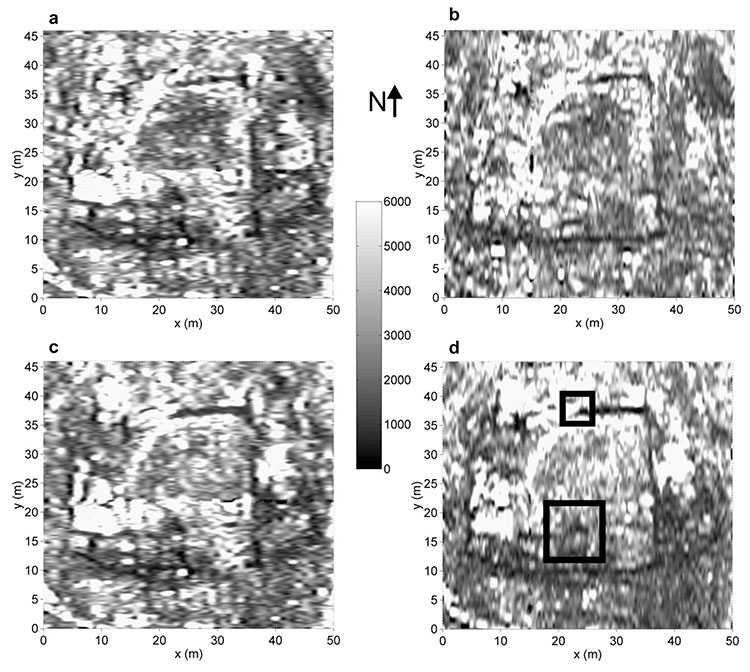

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the Journal of Archaeological Science, “Detecting and mapping buried buildings with Ground-Penetrating Radar at an ancient village in northwestern Argentina,” by Néstor Bonomo, Ana Osella, and Norma Ratto].

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the Journal of Archaeological Science, “Detecting and mapping buried buildings with Ground-Penetrating Radar at an ancient village in northwestern Argentina,” by Néstor Bonomo, Ana Osella, and Norma Ratto].

While reading The Losers last night for the first time—a graphic novel about a team of ex-CIA members now executing a series of elaborate heists against their former employer—I was pleasantly surprised to see that one of the final scenarios involves a small volcanic island featuring an abandoned village that had very recently been buried by ash and pumice.

In a nutshell, the buildings beneath all that rock and ash are still intact—and one of them contains a locked safe that our eponymous group of “losers” is searching for. So begins an unfortunately quite short scene of vertical archaeology: locating the proper building amidst the featureless landscape of ash, blasting a hole down through the building’s roof, stabilizing the ceiling from within so that heavy-lifting equipment can be installed on the rooftop, and then descending into the hallways and staircases below by way of mountaineering ropes to find the safe.

For whatever reason, there are few things I find more exciting to read about than high-risk descents into buried cities, especially one that, as in the case of The Losers, remains otherwise indistinguishable from the surface of the earth, only gradually revealing itself to be an extraordinary honeycomb of connected rooms and passages—and this brief moment in the book was made even more interesting when I remembered a handful of articles I’d saved last year, one of which also involves a lost village, buried by volcanic ash.

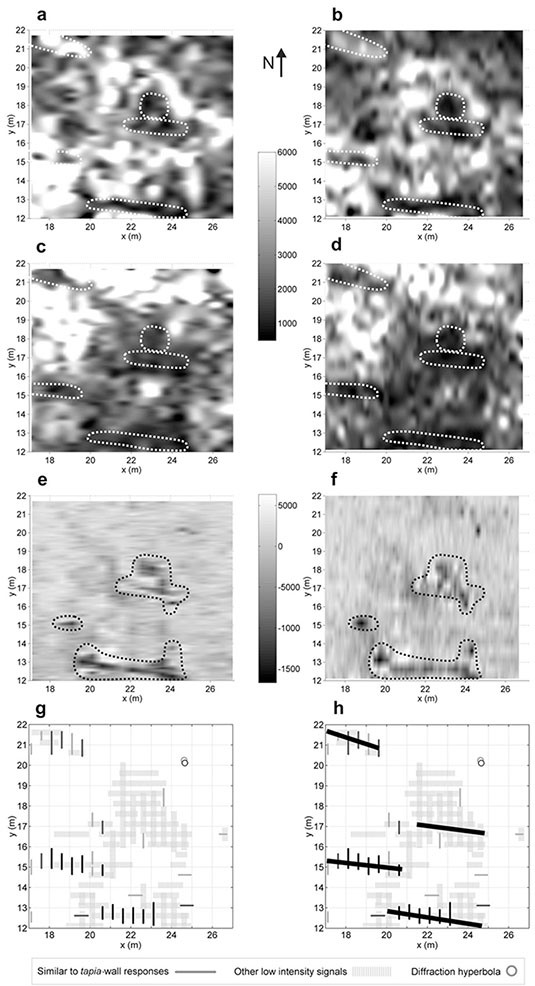

[Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the Journal of Archaeological Science, “Detecting and mapping buried buildings with Ground-Penetrating Radar at an ancient village in northwestern Argentina,” by Néstor Bonomo, Ana Osella, and Norma Ratto].

[Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the Journal of Archaeological Science, “Detecting and mapping buried buildings with Ground-Penetrating Radar at an ancient village in northwestern Argentina,” by Néstor Bonomo, Ana Osella, and Norma Ratto].

In a 1998 paper from the Journal of Applied Geophysics, called “The use of ground penetrating radar to map an ancient village buried by volcanic eruptions,” we read about a village in Japan called Komochi-mura, in Gunma prefecture: “The entire area surrounding the village is covered by a thick deposit of pumice derived from the eruption of Futatsudake volcano of Mt. Haruna, approximately 10km to the southwest of the village.”

Beneath the modern village, its predecessor from the middle of the 6th century is buried by the pumice deposits. Since these were laid down over a very short period, the ancient village should survive in a high state of preservation and will therefore contain much significant archaeological information. Ground penetrating radar (GPR) has been used to investigate this site over a period of 10 years. As a result, the plan of the ancient village can be accurately mapped… In this paper, the authors demonstrate how GPR was able to map the structural remains of the ancient village under a deposit of pumice.

In addition to various buildings, “pit-dwellings,” and other destroyed structures preserved but invisibly buried beneath today’s village, “traces of brushwood hedges, paths and other slight features have also been identified by the survey.”

These types of articles—on the remote-sensing of buried architectural remains, using technologies that “can detect and map buried structures without disturbing them,” in the words of the paper I am about to cite—are increasingly easy to find, but no less interesting because of their ubiquity.

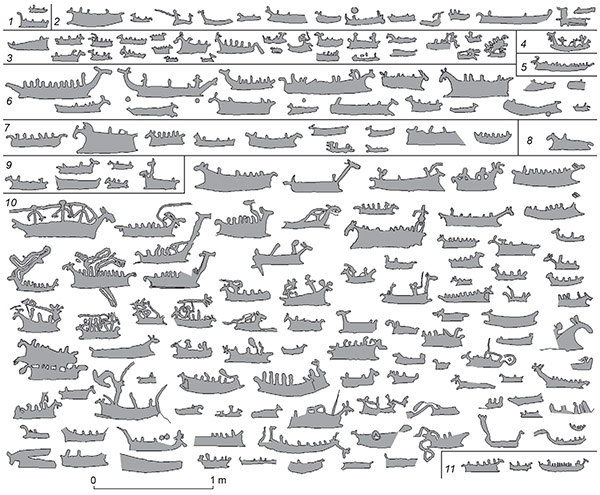

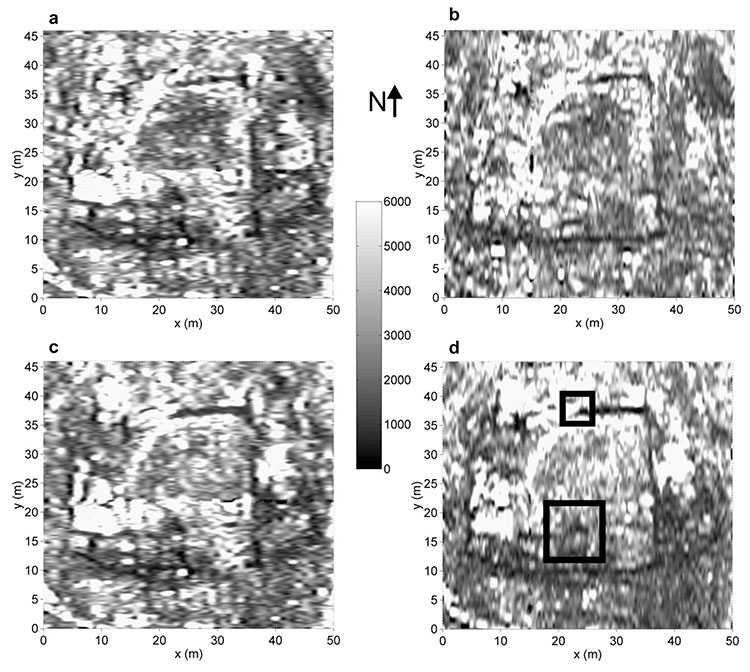

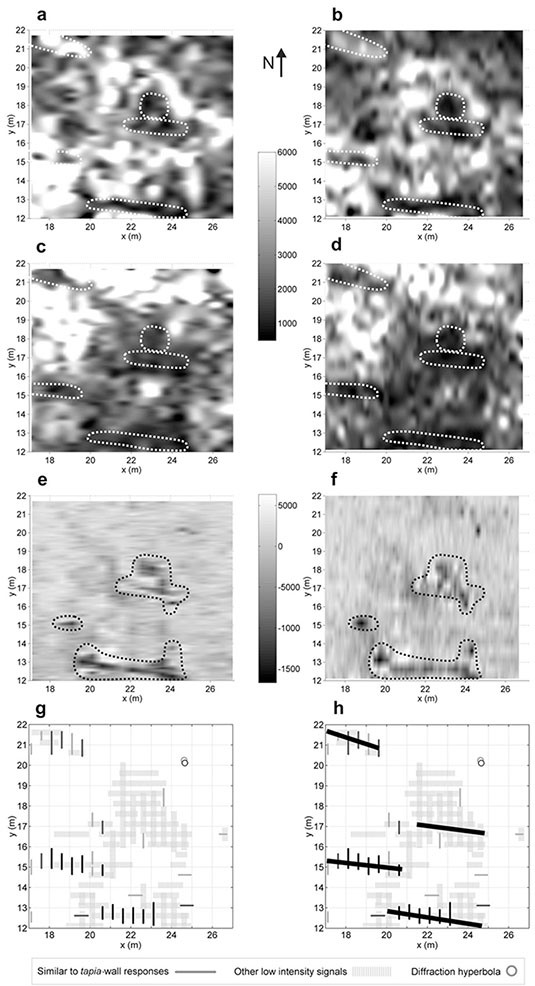

Another paper, then, called “Detecting and mapping buried buildings with Ground-Penetrating Radar at an ancient village in northwestern Argentina,” published in 2010 in the Journal of Archaeological Science, describes an archaeological survey in which ground-penetrating radar was used “in order to detect new buildings,” including a system of “complex wall distribution and a number of unknown enclosures.” These “new buildings,” however, were just signals from the earth awaiting spatial interpretation:

The exploration showed signals of mud-walls in a sector that was located relatively far from the previously known buildings. A detailed survey was performed in this sector, and the results showed that the walls belonged to a large dwelling with several rooms. The discovery of this dwelling has considerably extended the size of the site, showing that the dwellings occupied at least twice the originally assumed area. High-density GPR surveys were acquired at different parts of the discovered building in order to resolve complex structures. Interpreted maps of the building were obtained.

“From the joint analysis of the transverse sections, time slices and volume slices of the data and their time averaged intensity,” the authors explain, “we have obtained a final map for the new building”—where the “new” building, of course, is a much older, forgotten one, a structure interpretively remade and refreshed through this newfound legibility.

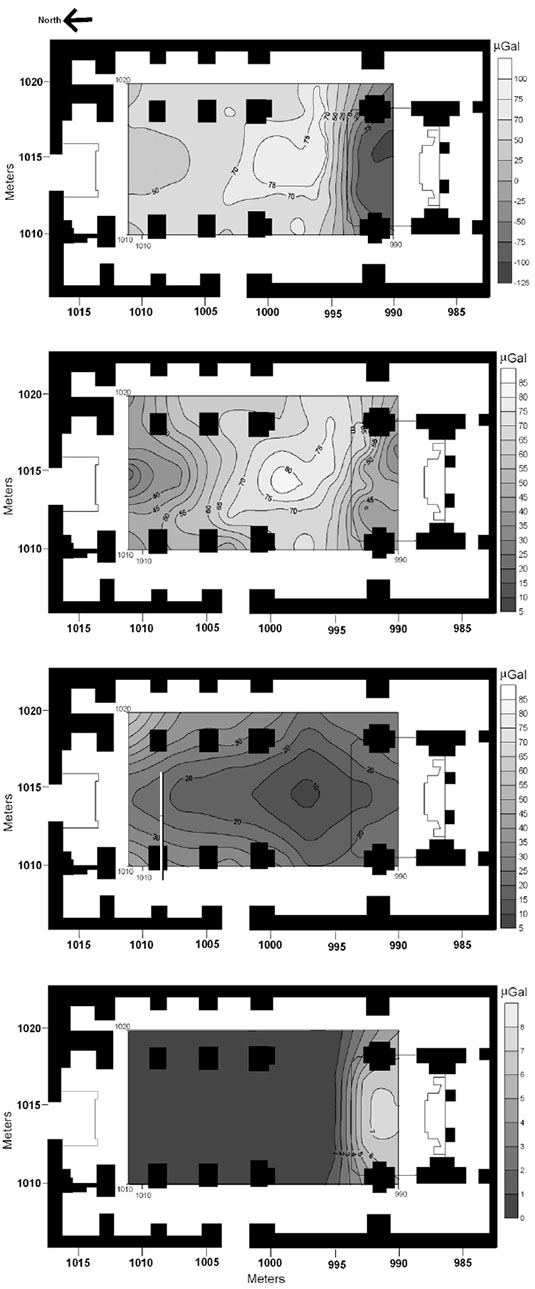

[Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science].

[Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science].

Architecture, in this context, comes to our attention first as a series of “intensity blots continued through consecutive slices,” an almost impossibly abstract geometry of signals and reflections, of patterned “electromagnetic responses” hidden in the landscape.

In all of these cases, it’d be interesting to propose a kind of archaeological discovery park the size of a football stadium, whose interior is simply a massive, open-span paved landscape on which small devices like floor-waxing machines or lawnmowers have been parked. Paying visitors can walk out onto this vast, continuous monument of bare concrete where they will begin moving the machines around, cautiously at first but then much more ambitiously, revealing as they do so the underground perimeters and outlines of entire villages buried deep in the mud and gravel beneath the building. The “park” is thus really a kind of terrestrial TV show of invisible architecture previously lost to history but beautifully preserved—that is, entombed—in the geology below.

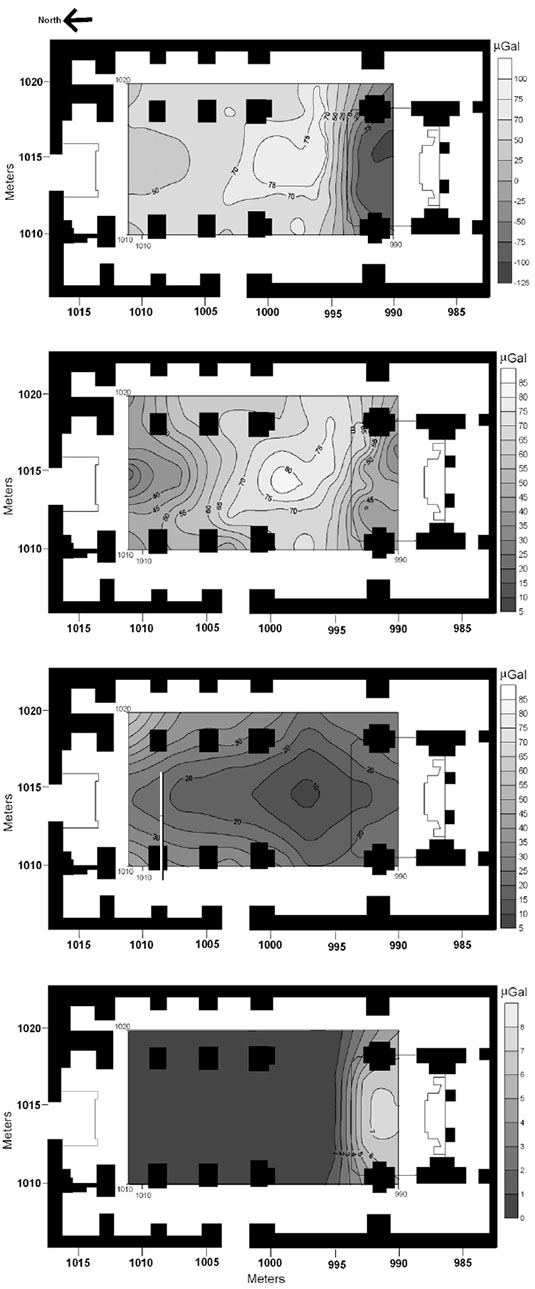

In any case, in writing this post I’ve realized that I’ve accumulated over the past two years or so several gigabytes’ worth of PDFs about these and other archaeological technologies—from mapping ancient ships buried in the Egyptian pyramids and micro-gravity detection of “shallow subsurface structures” in a church in Italy (“indicating,” in the authors’ words, “that the actual church was constructed above another one”) to “archaeomagnetic data” taken from Roman sites in Tunisia—but here’s at least one more reference for good measure.

In a paper called “Ground penetrating radar (G.P.R.) surveys applied to the research of crypts in San Sebastiano’s church in Catania (Sicily),” from a 2007 issue of the Journal of Cultural Heritage, a team of Italian geophysicists explored “natural or anthropic buried cavities” under a church in Sicily—that is, both architectural chambers and caves physically inaccessible in the foundations of the building. Soon enough, the authors write, “the existence of hidden structures was revealed.”

“In fact,” they add, “a crypt with a barrel vault, under the central aisle of the church, and a room of small dimensions next to this crypt were identified. Moreover, near the altar, the presence of a quadrangular crypt with a cross-vault was revealed. The presence of such buried masonries confirms that the church, rebuilt on previous building rests, has been subjected along the centuries to repeated repairs.”

[Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the regional tourism council].

[Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the regional tourism council].

There is something particularly awesome—that is, it is a story that lends itself particularly to metaphor—about envisioning a squad of well-equipped scientists setting up shop in a church in Sicily, using radar and rigs of strange antennae to scan the structure around them for secret rooms, heavenly nooks and crannies out of human reach. A kind of electromagnetic baroque.

The paper cited in a caption above—”Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, from a 2012 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science—even includes such strangely resonant lines as calculating against “residual gravity anomalies” in a “microgravimetric correction for the altar,” as if the high science of geophysical investigation has been rhetorically wed with theological speculation.

In the words of a paper by N. Farnoosh et al., published in a 2008 issue of NDT & E International, analyzing a given architectural space becomes a question of “buried target detection” using high-tech means—that is, establishing a sustained and coordinated “electromagnetic interaction among the radar antennas, ground, and buried objects.”

Here, the study of architectural history can very, very loosely be compared to astronomy: using tools of remote-sensing, including antennae, but targeted downward, into the earth, to reveal the flickering, gossamer traces of something that, for a variety of reasons, humans can’t yet physically reach. Like astronomy, then, archaeology and architectural history become a case of interpreting signals from afar, not of stars and supernovae but of lost rooms and buildings beneath our feet.

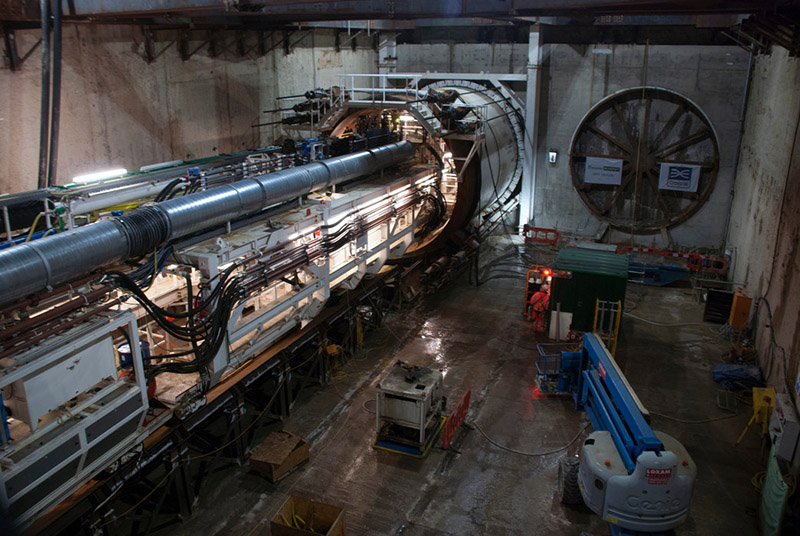

[Image: Machines slide beneath the streets, via Crossrail].

[Image: Machines slide beneath the streets, via Crossrail].

[Image: Looking down through shafts into the subcity, via Crossrail].

[Image: Looking down through shafts into the subcity, via Crossrail]. [Image: Phyllis, via Crossrail].

[Image: Phyllis, via Crossrail].

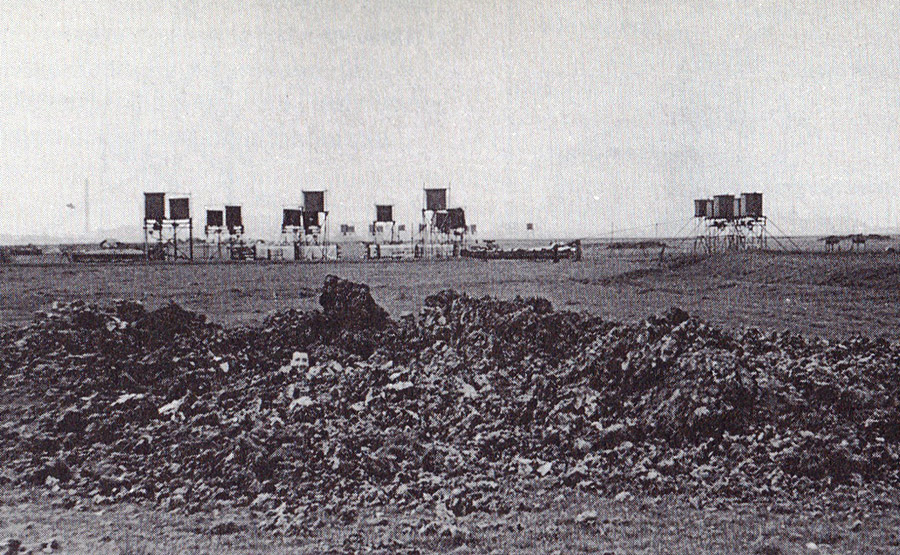

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of early night-vision technology used during the Vietnam War; courtesy of the

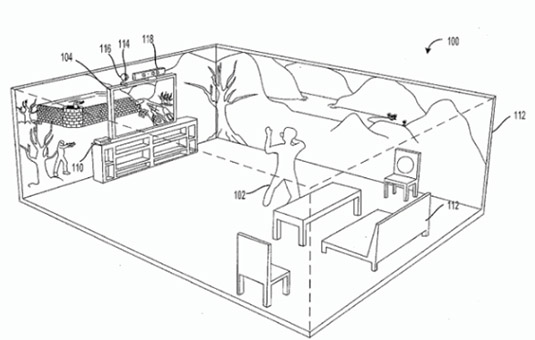

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of early night-vision technology used during the Vietnam War; courtesy of the  [Image: Microsoft’s

[Image: Microsoft’s

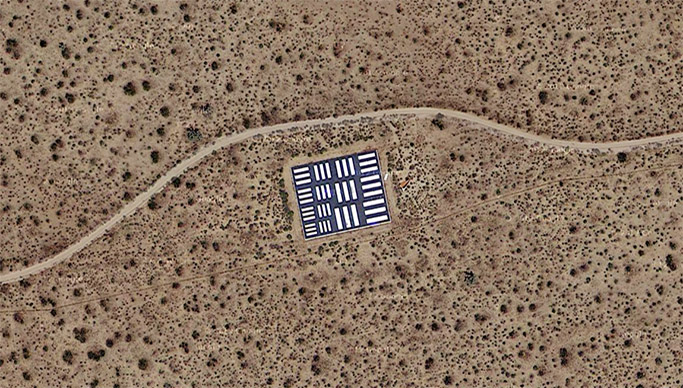

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of  [Image: A Starfish site burning, via the

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the  [Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the

[Image: Photo: The “cemetery and church at

[Image: Photo: The “cemetery and church at

[Image: (top) The “

[Image: (top) The “ [Image: Photo: The (

[Image: Photo: The ( [Image: Photo: The “remains of the lazy beds and enclosures at

[Image: Photo: The “remains of the lazy beds and enclosures at  [Images: Aerial view of

[Images: Aerial view of

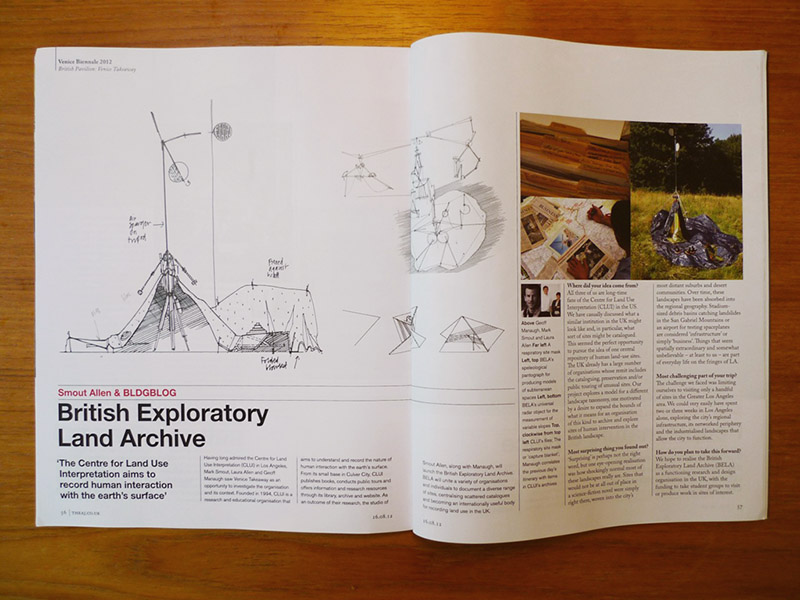

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: Green screen; image via

[Image: Green screen; image via

[Image: “Three tri-bar targets remaining at

[Image: “Three tri-bar targets remaining at  [Image: A tri-bar array at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; via

[Image: A tri-bar array at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; via  [Image: A “standard tri-bar test pattern on the Photo Resolution Range at Edwards that has been greatly expanded,”

[Image: A “standard tri-bar test pattern on the Photo Resolution Range at Edwards that has been greatly expanded,”  [Image: An “especially exotic” expanded tri-bar array at Fort Huachuca, Arizona; via

[Image: An “especially exotic” expanded tri-bar array at Fort Huachuca, Arizona; via

[Image: Calibration targets from the photo resolution range, Edwards Air Force Base; from

[Image: Calibration targets from the photo resolution range, Edwards Air Force Base; from

[Image: Hadrian’s Wall (not the wall described below) on the Whin Sill, via

[Image: Hadrian’s Wall (not the wall described below) on the Whin Sill, via

[Image: Recording a landscape; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via

[Image: Recording a landscape; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via  [Image: The team looks down at the earth they will soon record; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via

[Image: The team looks down at the earth they will soon record; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via  [Image: The petroglyphs; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via

[Image: The petroglyphs; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via  [Image: Boat glyphs from Lake Kanozero, courtesy of

[Image: Boat glyphs from Lake Kanozero, courtesy of  [Image: The petroglyphs and their tracing paper; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via

[Image: The petroglyphs and their tracing paper; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via  [Image: Field scaffolding set up to study rock art in Egypt; photo ©RMAH, Brussels, courtesy of

[Image: Field scaffolding set up to study rock art in Egypt; photo ©RMAH, Brussels, courtesy of

[Image: A piece of milled plexiglass acting as a projecting lens; via the

[Image: A piece of milled plexiglass acting as a projecting lens; via the  [Image: Reflections off glass or other polished surfaces could be controlled—that is, manipulated into producing recognizable images or specific shapes—by way of “caustic engineering”; Creative Commons photo by Flickr user

[Image: Reflections off glass or other polished surfaces could be controlled—that is, manipulated into producing recognizable images or specific shapes—by way of “caustic engineering”; Creative Commons photo by Flickr user

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

[Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the

[Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the  [Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the

[Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the