[Image: The Heathen Gate at Carnuntum, outside Vienna; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: The Heathen Gate at Carnuntum, outside Vienna; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

Last summer, a geophysicist at the University of Vienna named Immo Trinks proposed the creation of an EU-funded “International Subsurface Exploration Agency.” Modeled after NASA or the ESA, this new institute would spend its time, in his words, “looking downward instead of up.”

The group’s main goal would be archaeological: to map, and thus help preserve, sites of human settlement before they are lost to development, natural decay, climate change, and war.

Archaeologist Stefano Campana, at the University of Siena, has launched a comparable project called Sotto Siena, or “Under Siena”—abbreviated as SOS—intended to survey all accessible land in the city of Siena.

[Image: A few of Siena’s innumerable arches; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: A few of Siena’s innumerable arches; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

That project’s goal is primarily to catalog the region’s millennia of human habitation and cultural artifacts, but, like Immo Trinks and his proposed ISEA, is also serving to document modern-day infrastructure, such as pipes, utilities, sewers, and more. (When I met Campana in Siena last year, I was interested to learn that a man who had walked over to say hello, who was introduced to me as an enthusiastic supporter of Campana’s work, was actually Siena’s chief of police—it’s not just archaeologists who want to know what’s going on beneath the streets.)

I had the pleasure of tagging along with both Trinks and Campana last year as part of my Graham Foundation grant, “Invisible Cities,” and a brief write-up of that experience is now online over at WIRED.

The article begins in Siena, where I joined Campana and two technicians from the Livorno-based firm GeoStudi Astier for a multi-hour scan of parks, piazzas, and streets, using a ground-penetrating radar rig attached to a 4WD utility vehicle.

[Images: The GPR rig we rode in that day, owned and operated by GeoStudi Astier; photos by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Images: The GPR rig we rode in that day, owned and operated by GeoStudi Astier; photos by Geoff Manaugh.]

We stayed out well past midnight, at one point scanning a piazza in front of the world’s oldest bank, an experience that brought back positive memories from my days reporting A Burglar’s Guide to the City (alas, we didn’t discover a secret route into or out of the vault, but just some fountain drains).

In Vienna, meanwhile, Trinks drove me out to see an abandoned Roman frontier-city and military base called Carnuntum, near the banks of the Danube, where he walked me through apparently empty fields and meadows while narrating all the buildings and streets we were allegedly passing through—an invisible architecture mapped to extraordinary detail by a combination of ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry.

“We want to map it all—that’s the message,” Trinks explained to me. “You’re not just mapping a Roman villa. You’re not mapping an individual building. You are mapping an entire city. You are mapping an entire landscape—and beyond.”

An estimated 99% of Carnuntum remains unexcavated, which means that our knowledge of its urban layout is almost entirely mediated by electromagnetic technology. This, of course, presents all sorts of questions—about data, machine error, interpretation, and more—that were explained to me on a third leg of that trip, when I traveled to Croatia to meet Lawrence B. Conyers.

[Image: A gorge leading away behind the archaeological site I visited on the island of Brač, Croatia; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: A gorge leading away behind the archaeological site I visited on the island of Brač, Croatia; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

Conyers is an American ground-penetrating radar expert who, when we met, was spending a couple of weeks out on the island of Brač, near the city of Split. He had traveled there to scan a hilltop site, looking for the radar signatures of architectural remains, in support of a project sponsored by the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Conyers supplies a voice of caution in the WIRED piece, advising against over-relying on expensive machines for large-scale data collection if the people hoarding that data don’t necessarily know how to filter or interpret it.

[Image: Lawrence Conyers supervises two grad students using his ground-penetrating radar gear; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: Lawrence Conyers supervises two grad students using his ground-penetrating radar gear; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

The goal of an International Subsurface Exploration Agency could rise or fall, in other words, not just on questions of funding or public support, but on the limits of software analysis and human interpretation: are we sure that what we see on the screens of our machines is actually there, underground?

When we spoke in Siena, Campana used the metaphor of a medical biopsy, insisting that archaeologists and geophysicists will always need to excavate, not just for the recovery of historical artifacts and materials, but for verifying their own hypotheses, literally testing the ground for things they think they’ve seen there.

Archaeologist Eileen Ernenwein, co-editor of the journal Archaeological Prospection, also emphasized this to me when I interviewed her for WIRED, adding a personal anecdote that has stuck with me. During her graduate thesis research, Ernenwein explained, she found magnetic evidence of severely eroded house walls at an indigenous site in New Mexico, but, after excavating to study them, realized that the structure was only visible in the electromagnetic data. It was no less physically real for only being visible magnetically—yet excavation alone would have almost certainly have missed the site altogether. She called it “the invisible house.”

In any case, many things have drawn me to this material, but the long-term electromagnetic traces of our built environment get very little discussion in architectural circles, and I would love this sort of legacy to be more prominently considered. What’s more, our cultural obsession with ruins will likely soon begin to absorb new sorts of images—such as radar blurs and magnetic signatures of invisible buildings—signaling an art historical shift in our representation of the architectural past.

For now, check out the WIRED article, if you get a chance.

(Thanks again to the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts for supporting this research. Related: Through This Building Shines The Cosmos.)

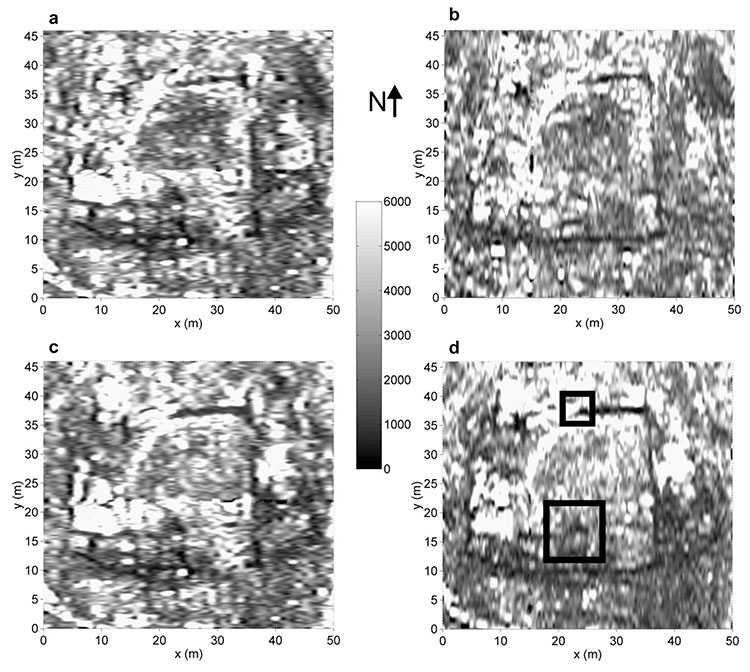

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

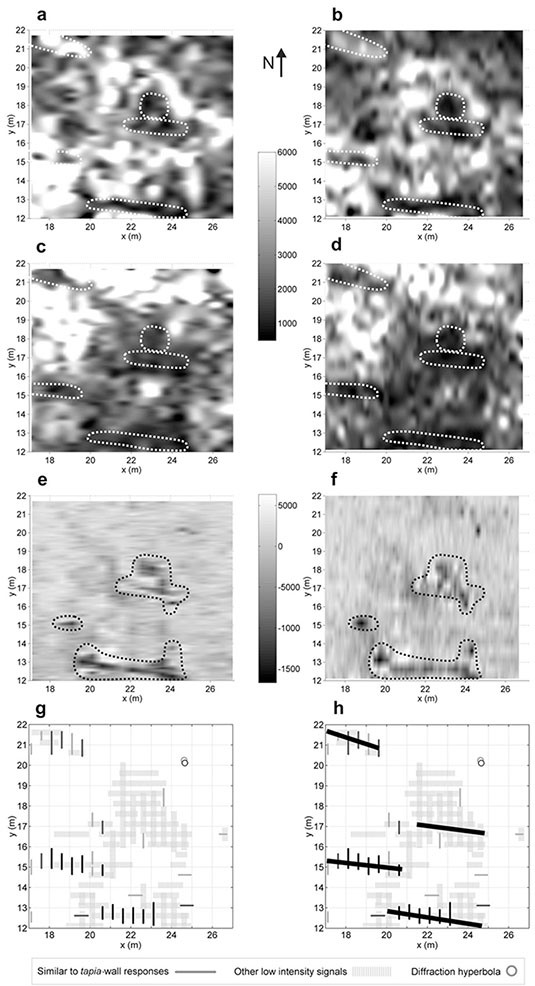

[Image: “Constant time slices” reveal buildings buried in northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the

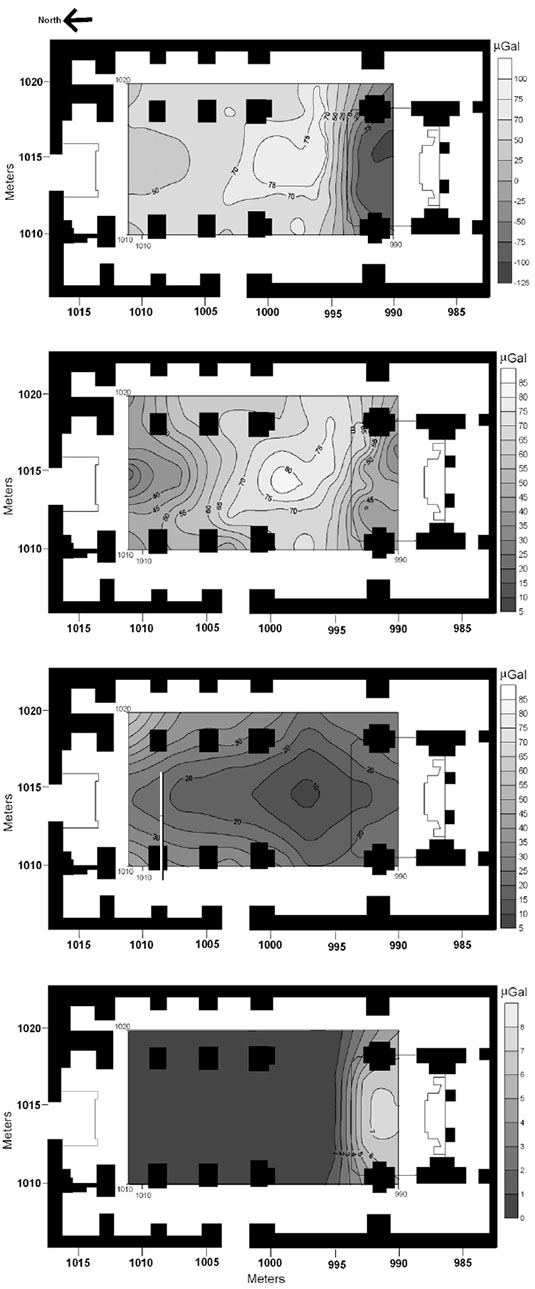

[Image: A selection of “time slices” from the buried buildings of northwestern Argentina; image from, and courtesy of, the  [Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the

[Image: From “Archaeological microgravimetric prospection inside don church (Valencia, Spain),” by Jorge Padín, Angel Martín, Ana Belén Anquela, in a 2012 issue of the  [Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the

[Image: The church of San Sebastiano in Catania, Sicily, courtesy of the