[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

[Image: A Starfish site, like a pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

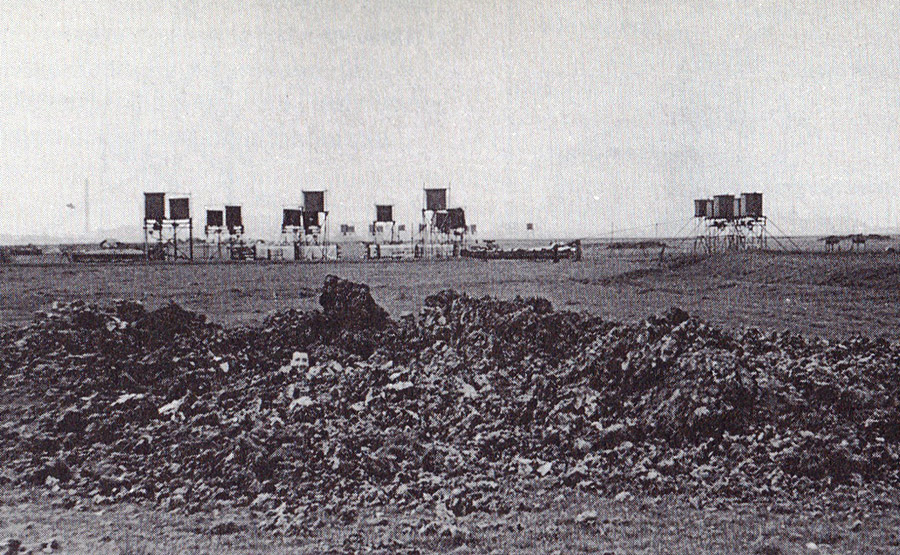

A few other things that will probably come up this evening at the Architectural Association, in the context of the British Exploratory Land Archive project, are the so-called “Starfish sites” of World War II Britain. Starfish sites “were large-scale night-time decoys created during The Blitz to simulate burning British cities.”

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

[Image: A Starfish site burning, via the St. Margaret’s Community Website; view larger].

Their nickname, “Starfish,” comes from the initials they were given by their designer, Colonel John Turner, for “Special Fire” sites or “SF.”

As English Heritage explains, in their list of “airfield bombing decoys,” these misleading proto-cities were “operated by lighting a series of controlled fires during an air raid to replicate an urban area targeted by bombs.” They would thus be set ablaze to lead German pilots further astray, as the bombers would, at least in theory, fly several miles off-course to obliterate nothing but empty fields camouflaged as urban cores.

They were like optical distant cousins of the camouflaged factories of Southern California during World War II.

Being in a hotel without my books, and thus relying entirely on the infallible historical resource of Wikipedia for the following quotation, the Starfish sites “consisted of elaborate light arrays and fires, controlled from a nearby bunker, laid out to simulate a fire-bombed town. By the end of the war there were 237 decoys protecting 81 towns and cities around the country.”

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the St. Margaret’s Community Website].

[Image: Zooming-in on the Starfish site, seen above; image via the St. Margaret’s Community Website].

The specific system of visual camouflage used at the sites consisted of various special effects, including “fire baskets,” “glow boxes,” reflecting pools, and long trenches that could be set alight in a controlled sequence so as to replicate the streets and buildings of particular towns—1:1 urban models built almost entirely with light.

In fact, in some cases, these dissimulating light shows for visiting Germans were subtractively augmented, we might say, with entire lakes being “drained during the war to prevent them being used as navigational aids by enemy aircraft.”

Operational “instructions” for turning on—that is, setting ablaze—”Minor Starfish sites” can be read, courtesy of the Arborfield Local History Society, where we also learn how such sites were meant to be decommissioned after the war. Disconcertingly, despite the presence of literally tons of “explosive boiling oil” and other highly flammable liquid fuel, often simply lying about in open trenches, we read that “sites should be de-requisitioned and cleared of obstructions quickly in order to hand the land back to agriculture etc., as soon as possible.”

The remarkable photos posted here—depicting a kind of pyromaniac’s version of Archigram, a temporary circus of flame bolted together from scaffolding—come from the St. Margaret’s Community Website, where a bit more information is available.

In any case, if you’re around London this evening, Starfish sites, aerial archaeology, and many other noteworthy features of the British landscape will be mentioned—albeit in passing—during our lecture at the Architectural Association. Stop by if you’re in the neighborhood…

(Thanks to Laura Allen for first pointing me to Starfish sites).

I heard a radio interview with someone who worked at a similar site that was designed to mimic a airstrip as well. It had many elaborate sounding rigs such as torches tied to strings and pulleys to simulate moving planes and vehicles etc. Obviously in those days this had to all be manually

arranged and operated. He also pointed out the strange situation of hearing bombers overhead and going out to try your damnedest to make them drop bombs right on you.