The origin of the television set was heavily shrouded in both spiritualism and the occult, Stefan Andriopoulos writes in his new book Ghostly Apparitions. In fact, as its very name implies, the television was first conceived as a technical device for seeing at a distance: like the telephone (speaking at a distance) and telescope (viewing at a distance), the television was intended as an almost magical box through which we could watch distant events unfold, a kind of technological crystal ball.

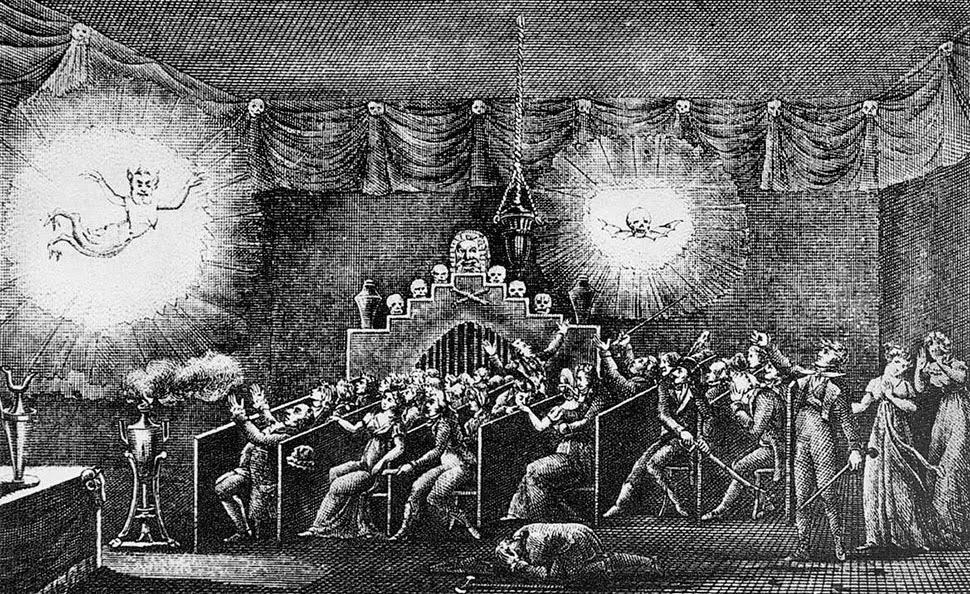

Andriopoulos’s book puts the TV into a long line of other “optical media” that go back at least as far as popular Renaissance experiments involving technologically-induced illusions, such as concave mirrors, magic lanterns, disorienting walls of smoke, and other “ghostly apparitions” and “phantasmagoric projections” created by specialty devices. These were conjuring tricks, sure—mere public spectacles, so to speak—but successfully achieving them required sophisticated understandings of basic physical factors such as light, shadow, and acoustics, making an audience see—and, most importantly, believe in—the illusion.

A Magic Lantern for Watching Events at a Distance

What’s central to Andriopoulos’s argument is that these devices incorporated earlier experimental instruments devised specifically for pursuing supernatural research—for visualizing the invisible and showing the subtle forces at work in everyday life. In his words, these were “devices developed in occult research”—including explicitly “televisionlike devices”—that had been invented in the name of spiritualism toward the end of the 19th century and that, only a decade or two later, “played a constitutive role in the emergence of radio and television.”

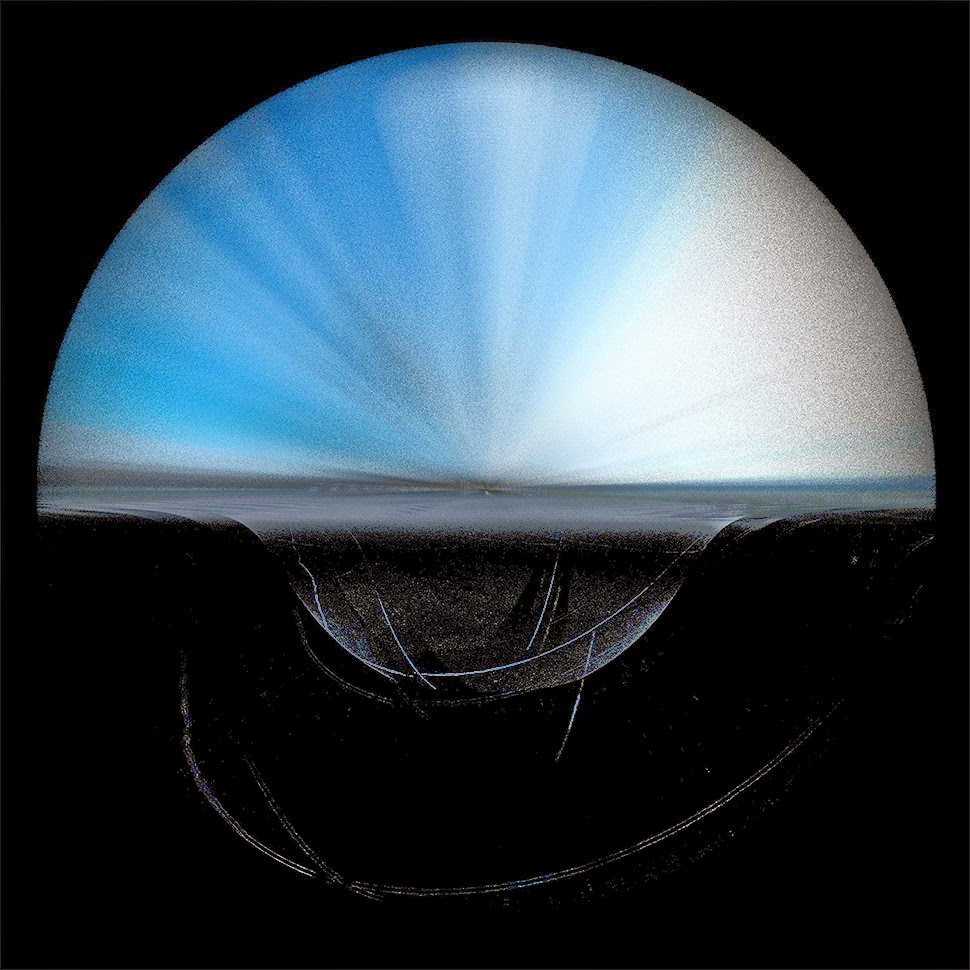

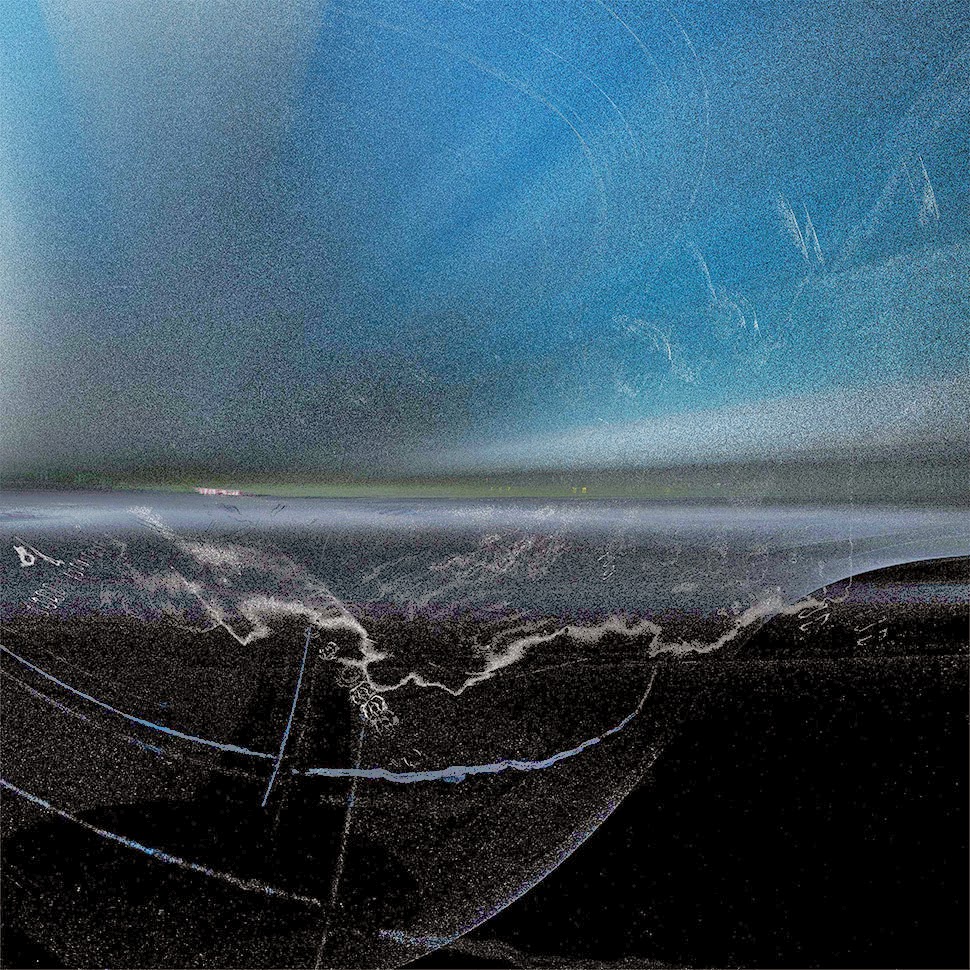

[Image: From Etienne-Gaspard Robertson’s 1834 study of technical phantasmagoria, via Ghostly Apparitions].

[Image: From Etienne-Gaspard Robertson’s 1834 study of technical phantasmagoria, via Ghostly Apparitions].

In Andriopoulos’s words, this was simply part of “the reciprocal interaction between occultism and the natural sciences that characterized the cultural construction of new technological media in the late nineteenth century,” a “two-directional exchange between occultism and technology.” New forms of broadcast technology and belief in the occult? No big deal.

So, while the television itself—the object you and I most likely know as the utterly mundane fixture of family distraction sitting centrally ensconced in a nearby living room—might not be a supernatural mechanism, it nonetheless descends from a strange and convoluted line of esoteric experimentation, including early attempts at controlling electromagnetic transmissions, directing radio waves, and even experiencing various forms of so-called “remote viewing.”

The idea of a medium takes on a double meaning here, Andriopoulos explains, as the word refers both to the media—in the sense of a professional world of publishing and transmission—and to the medium, in the sense of a specific, vaguely shamanic person who acts as a psychic or seer. The medium thus acts as an intermediary between humans and the supernatural world in a very literal sense.

Indeed, in Andriopoulos’s version of television’s origin story, the notion of spiritual clairvoyance was very much part of the overall intention of the device.

Clairvoyance—a word that literally means clear vision, yet that has now come to refer almost exclusively to a supernatural ability to see things at a distance or before events even happen—offered an easy metaphor for this new mechanism.

Television promised clairvoyance in the sense that a TV could allow seeing without interference or noise. It would give viewers a way to tune into and clearly see a broadcast’s invisible signals—with the implication that an esoteric remote-viewing apparatus with forgotten supernatural intentions is now mounted and enshrined in nearly everyone’s home.

[Image: A “moving face” transmitted by John Logie Baird at a public demonstration of TV in 1926 (photo via the BBC)].

[Image: A “moving face” transmitted by John Logie Baird at a public demonstration of TV in 1926 (photo via the BBC)].

I’ll leave it to curious readers to look for Andriopoulos’s book itself—with the caveat that it is quite heavy on German idealism and rather light on real tech history—but it is worth mentioning the fact that at least one other technical aspect of the 20th-century television also followed a very bizarre historical trajectory.

Part Tomb, Part Church, Part Planetarium

The cathode ray—a vacuum tube technology found in early television sets—took on an unexpected and extraordinary use in the work of gonzo Norwegian inventor Kristian Birkeland. Birkeland used cathode rays in his attempt to build a doomed scale model of the solar system.

I genuinely love this story and I have written about it elsewhere, including both here on BLDGBLOG and in The BLDGBLOG Book, but it’s well worth retelling.

In a nutshell, Birkeland was the first scientist to correctly hypothesize the origins of the Northern Lights, rightly deducing from his own research into electromagnetic phenomena that the aurora borealis was actually caused by interactions between charged particles constantly streaming toward earth from the sun and the earth’s own protective magnetic field. This produced the extraordinary displays of light Birkeland had seen in the planet’s far north.

However, as Birkeland fell deeper into an eventually fatal addiction to extreme levels of caffeine and a slow-acting hypnotic drug called Veronal, he also—awesomely—became fixated on the weirdly impossible goal of precisely modeling the Northern Lights in miniature. He sought to build a kind of Bay Model of the Northern Lights.

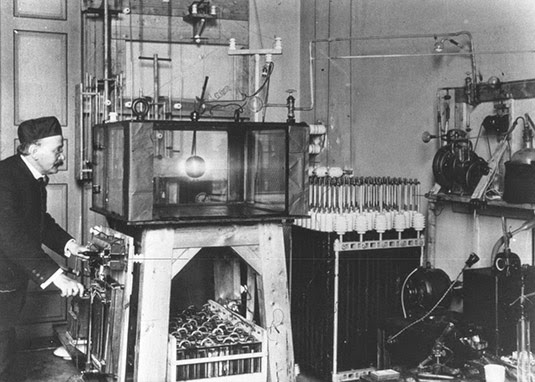

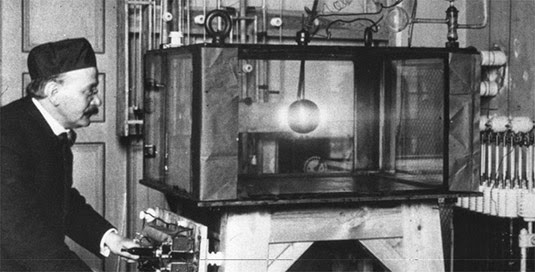

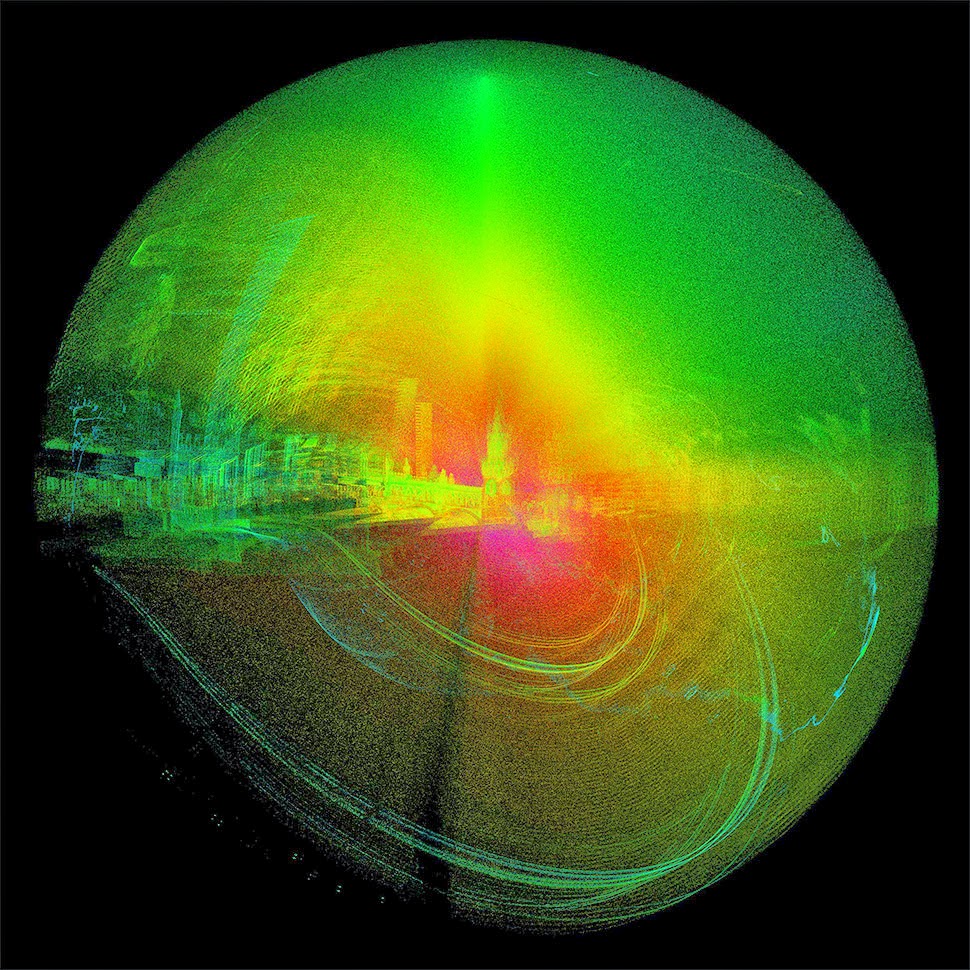

[Image: Kristian Birkeland stares deeply into his universal simulator (via)].

[Image: Kristian Birkeland stares deeply into his universal simulator (via)].

As author Lucy Jago tells Birkeland’s amazing story in her book The Northern Lights, he was intent on producing a kind of astronomical television set: a “televisionlike device,” in Andriopoulos’s words, whose inner technical workings would not just broadcast actions and characters seen elsewhere, but would actually model the electromagnetic secrets of the universe.

As Jago describes his project, Birkeland “drew up plans for a new machine unlike anything that had been made before.” It resembled “a spacious aquarium,” she writes, a shining box that would act as “a window into space.”

The box would be pumped out to create a vacuum and he would use larger globes and a more powerful cathode to produce charged particles. With so much more room he would be able to see effects, obscured in the smaller tubes, that could take his Northern Lights theory one step further–into a complete cosmogony, a theory of the origins of the universe.

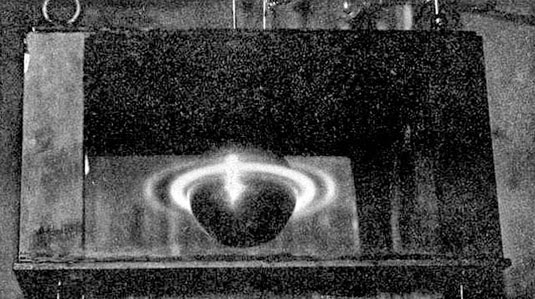

It was a multifaceted and extraordinary undertaking. With it, Jago points out, “Birkeland was able to simulate Saturn’s rings, comet tails, and the Zodiacal Light. He even experimented with space propulsion using cathode rays. Sophisticated photographs were taken of each simulation, to be included in the next volume of Birkeland’s great work, which would discern the electromagnetic nature of the universe and his theories about the formation of the solar system.”

However, this “spacious aquarium” was by no means the end of Birkeland’s manic (tele)vision.

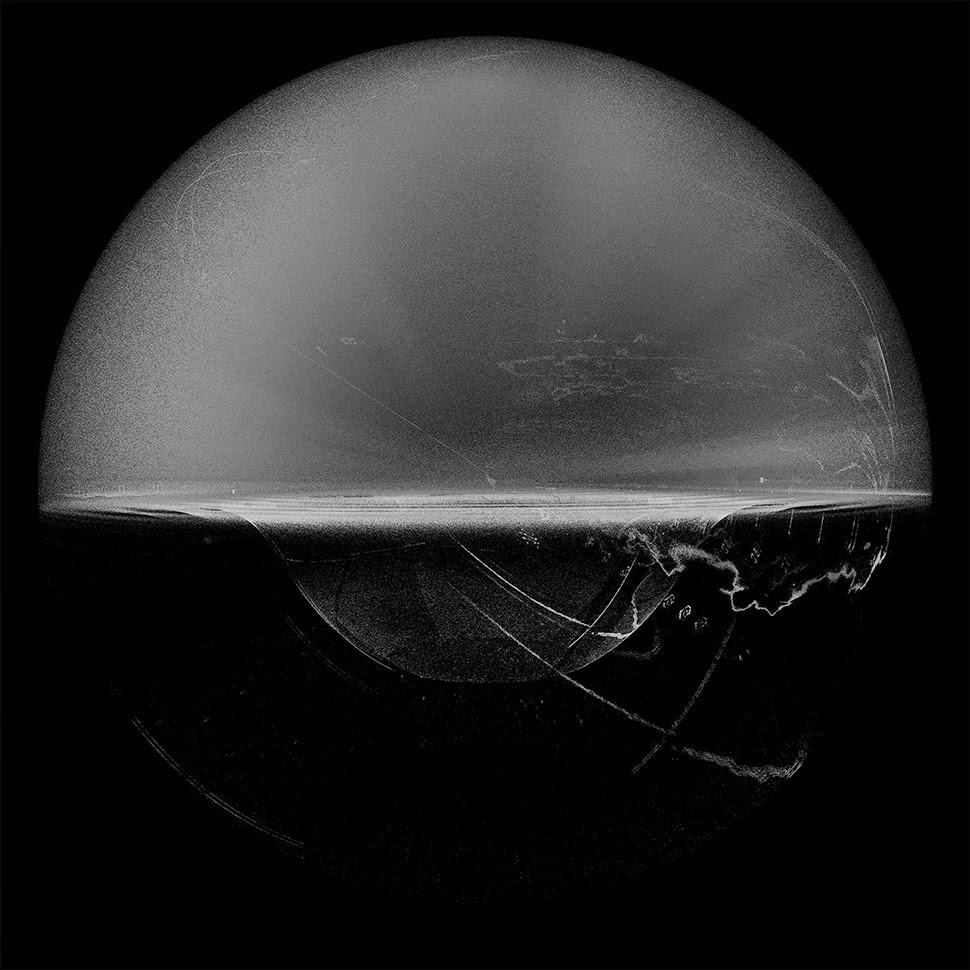

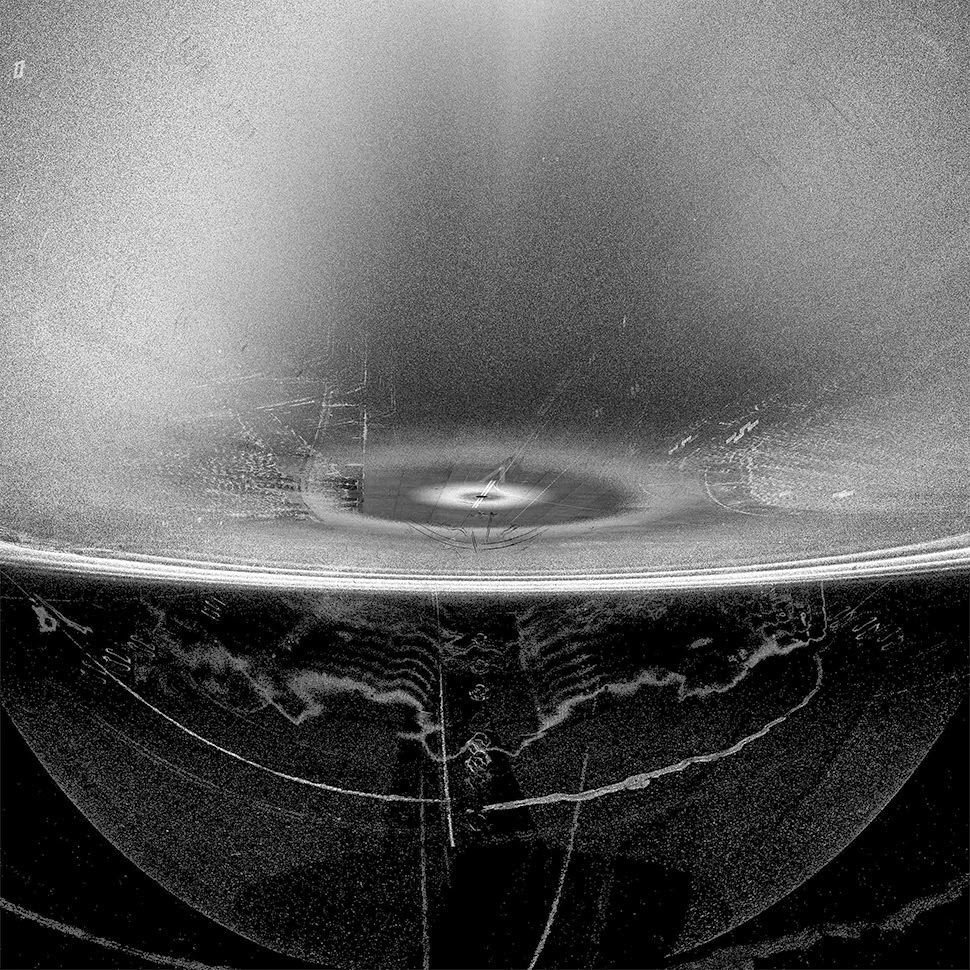

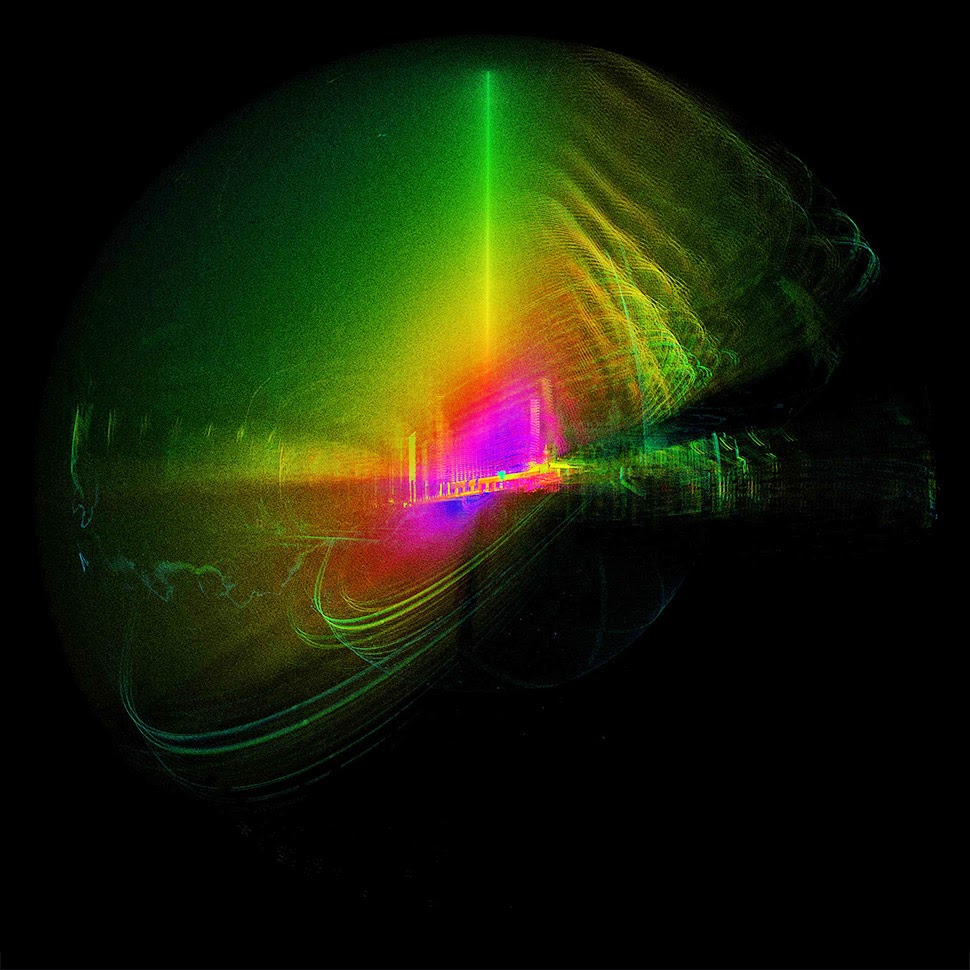

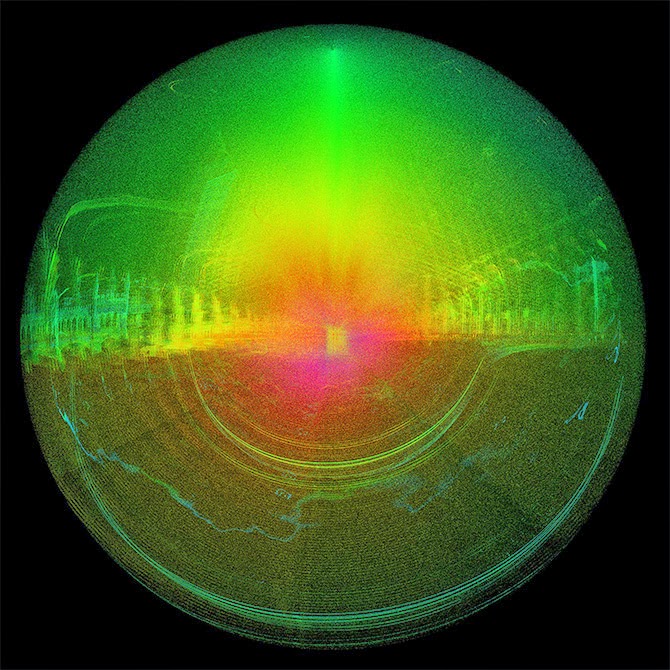

[Image: From Birkeland’s The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903, Vol. 1: On the Cause of Magnetic Storms and The Origin of Terrestrial Magnetism (via)].

[Image: From Birkeland’s The Norwegian Aurora Polaris Expedition 1902-1903, Vol. 1: On the Cause of Magnetic Storms and The Origin of Terrestrial Magnetism (via)].

His ultimate goal—devised while near-death in a hotel room in Egypt—was to construct a vacuum chamber partially excavated into the solid rock of a mountain peak, an insane mixture of tomb, church, and planetarium.

The resulting cathedral-like space—think of it as a three-dimensionally immersive, landscape-scale television set carved directly into bedrock—would thus be an artificial cavern inside of which flickering electric mirages of stars, planets, comets, and aurorae would spiral and glow for a hypnotized audience.

Birkeland wrote about this astonishing plan in a letter to a friend. He was clearly excited about what he called a “great idea I have had.” It would be—and the emphasis is all Birkeland’s—”a museum for the discovery of the Earth’s magnetism, magnetic storms, the nature of sunspots, of planets—their nature and creation.”

His excitement was justified, and the ensuing description is worth quoting at length; you can almost feel the caffeine. “On a little hill,” he scribbled, presumably on his Egyptian hotel’s own stationery, perhaps even featuring a little image of the pyramids embossed in its letterhead, reminding him of the ambitions of long-dead pharaohs, “I will build a dome of granite, the walls will be a meter thick, the floor will be formed of the mountain itself and the top of the dome, fourteen meters in diameter, will be a gilded copper sphere. Can you guess what the dome will cover? When I’m boasting I say to my friends here ‘next to God, I have the greatest vacuum chamber in the world.’ I will make a vacuum chamber of 1,000 cubic metres and, every Sunday, people will have the opportunity to see a ring of Saturn ten metres in diameter, sunspots like no one else can do better, Zodiacal Light as evocative as the natural one and, finally, auroras… four meters in diametre. The same sphere will serve as Saturn, the sun, and Earth, and will be driven round by a motor.”

Every Sunday, as if attending Mass, congregants of this artificial solar system would thus hike up some remote mountain trail, heading deep into the cavernous and immersive television of Birkeland’s own astronomy, hypnotized by the explosive whirls of its peculiar, peacock-like displays of electromagnetism, shimmering cathedrals of artificially controlled planetary light.

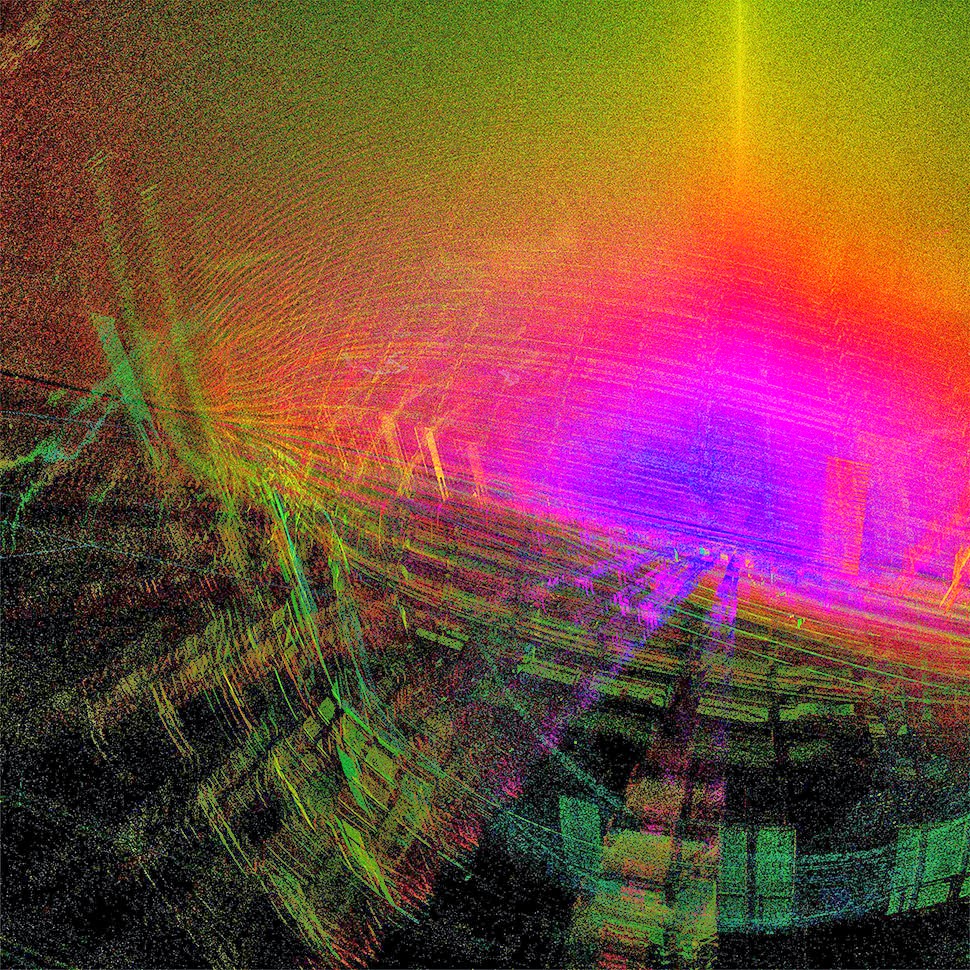

[Image: Cropping in on the pic seen above (via)].

[Image: Cropping in on the pic seen above (via)].

Seen in the context of the occult mechanisms, psychic TVs, and clairvoyant media technologies of Stefan Andriopoulos’s book, Birkeland’s story reveals just one particularly monumental take on the other-worldly possibilities implied by televisual media, bypassing the supernatural altogether to focus on something altogether more extreme: a direct visual engagement with nature itself, in all its blazing detail.

Of course, Birkeland’s cathode ray model of the solar system might not have conjured ghosts or visualized the spiritual energies that Andriopoulous explores in his book, but it did try to bring the heavens down to earth in the form of a 1,000 cubic meter television set partially hewn from mountain granite.

It was the most awesome TV ever attempted, a doomed and never-realized invention that nonetheless puts all of today’s visual media to shame.

(An earlier version of this post previously appeared on Gizmodo).

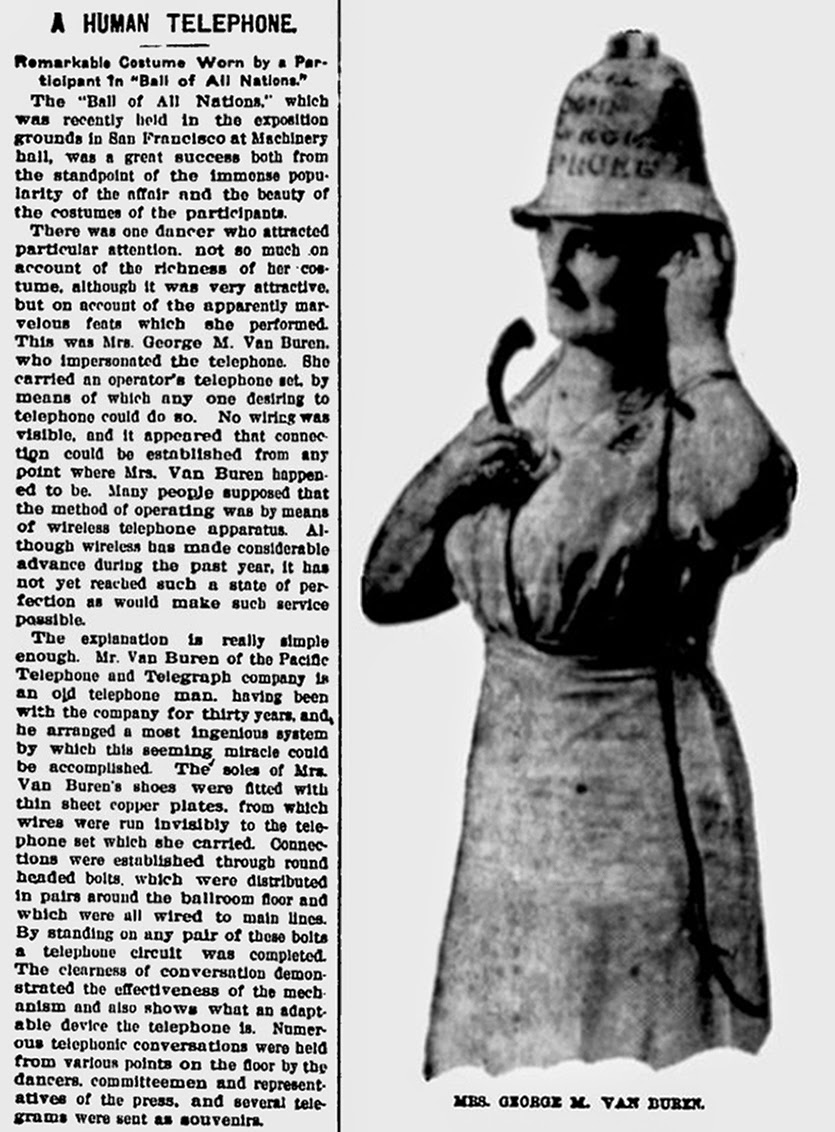

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914].

[Image: From the Ellensburg Daily Record, June 16, 1914]. [Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

[Image: An otherwise irrelevant photo of people ballroom dancing, via

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy

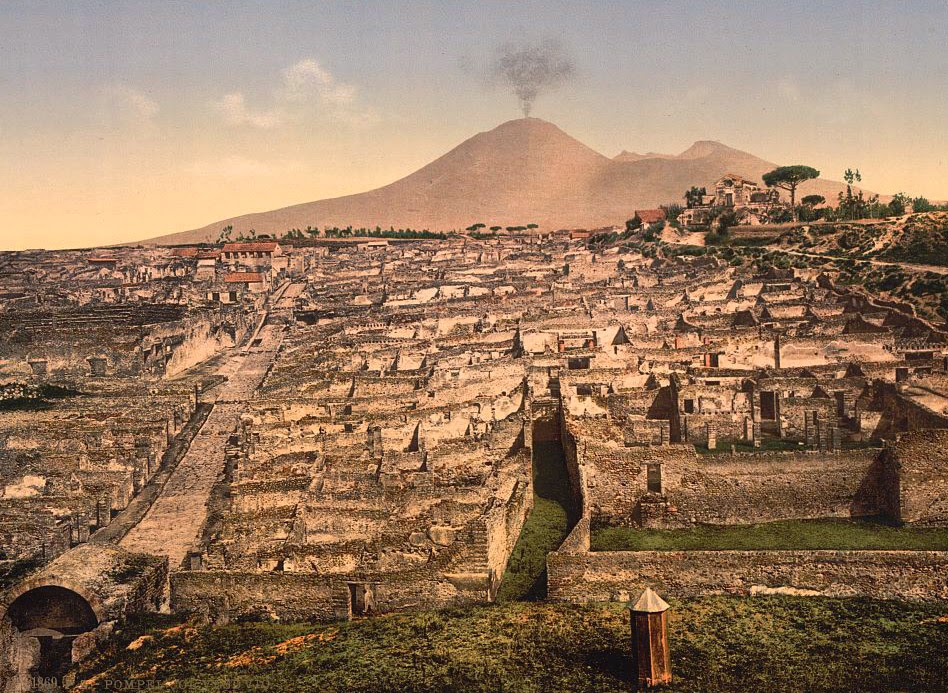

[Image: Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, steps forth into the ruins of the “extinct city” of Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy

[Image: General view of Pompeii and Mt. Vesuvius; courtesy  [Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Street of Tombs, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy

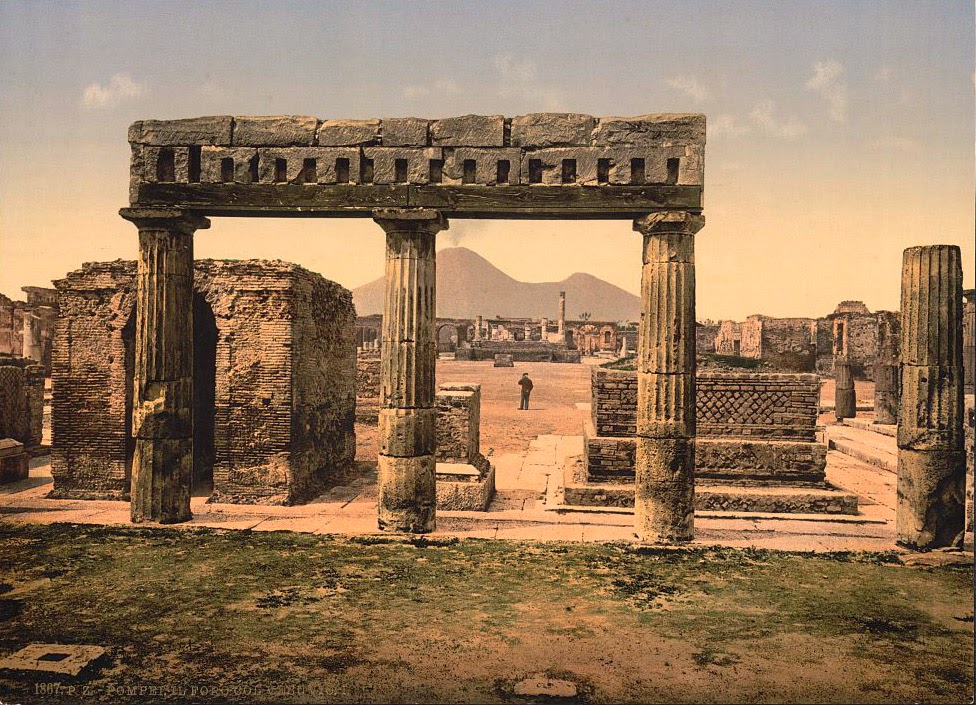

[Image: Fortuna Street, Pompeii; courtesy  [Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image: The Forum, Pompeii; courtesy

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Images: Photos courtesy of the

[Images: Photos courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Image: Photo courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of the  [Images: Photos courtesy of the

[Images: Photos courtesy of the

[Image: Collage by

[Image: Collage by  [Image: Inside a wind tunnel, courtesy of NASA, via

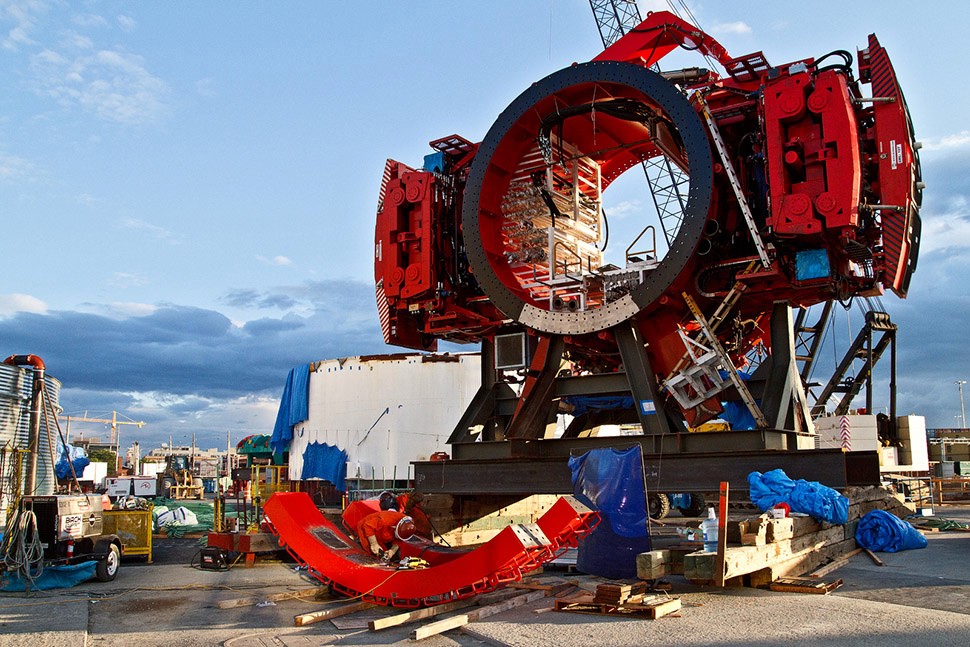

[Image: Inside a wind tunnel, courtesy of NASA, via  [Image: Bertha, a tunneling

[Image: Bertha, a tunneling

[Image: Internal title page from

[Image: Internal title page from

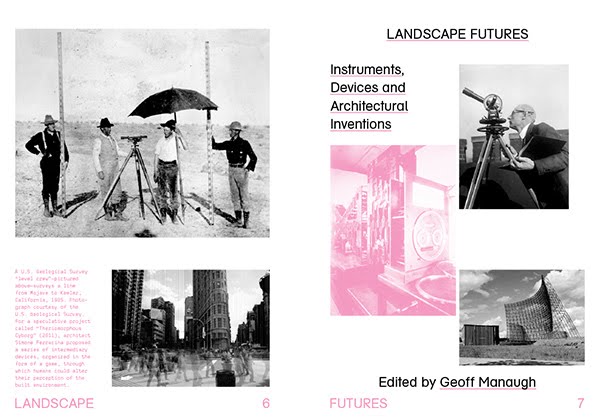

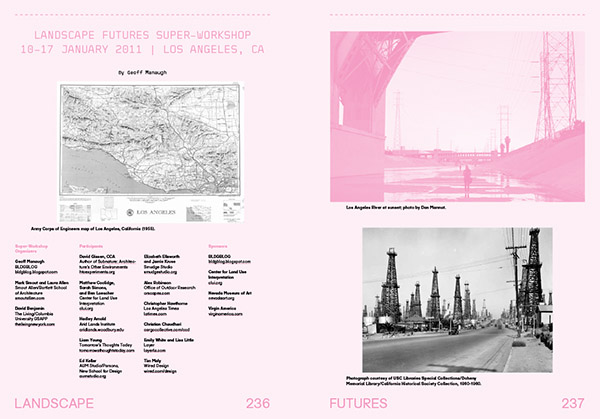

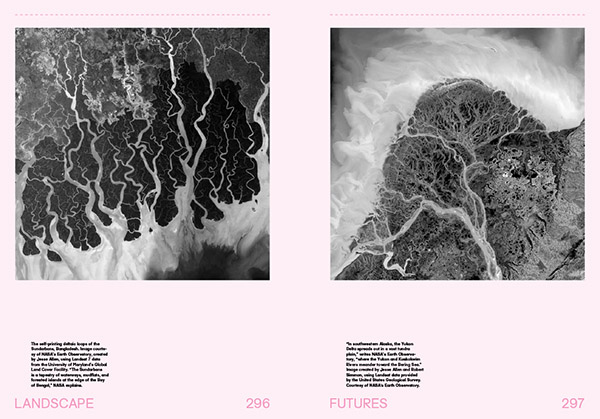

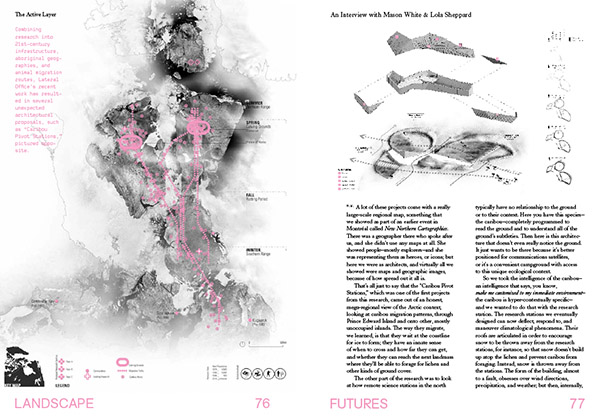

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

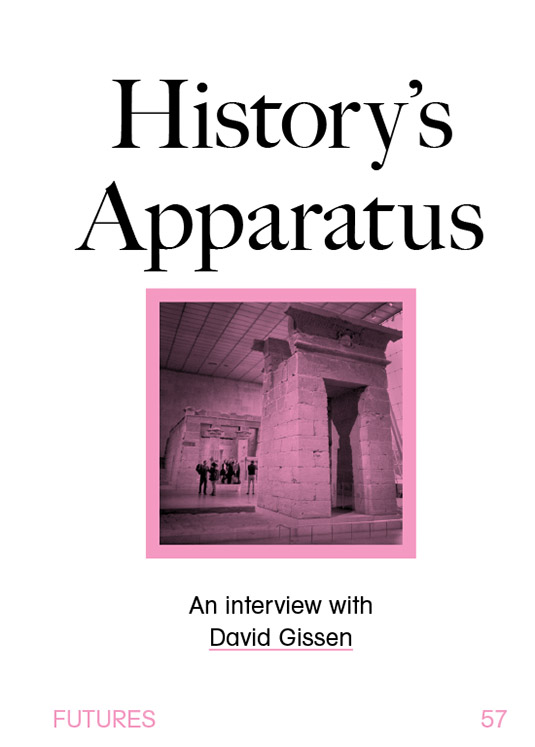

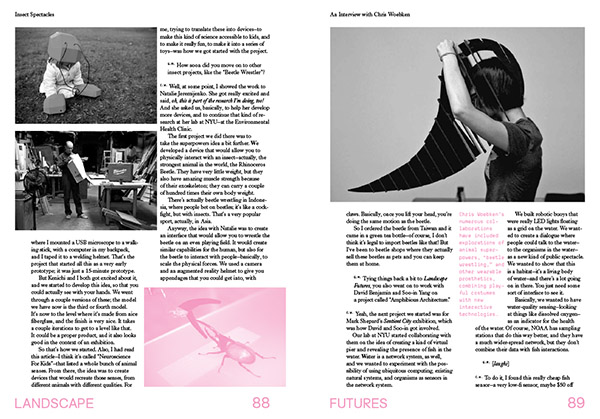

[Images: Interview spreads from

[Images: Interview spreads from

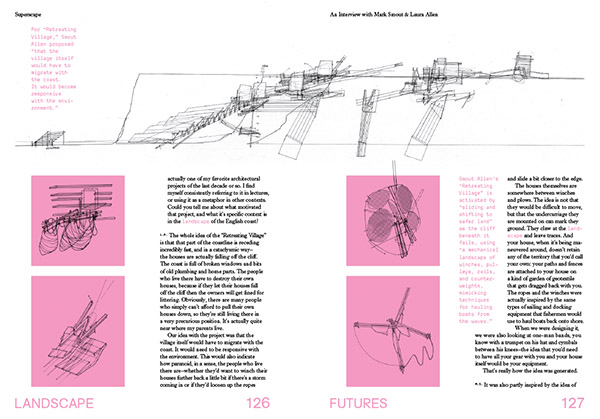

[Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “

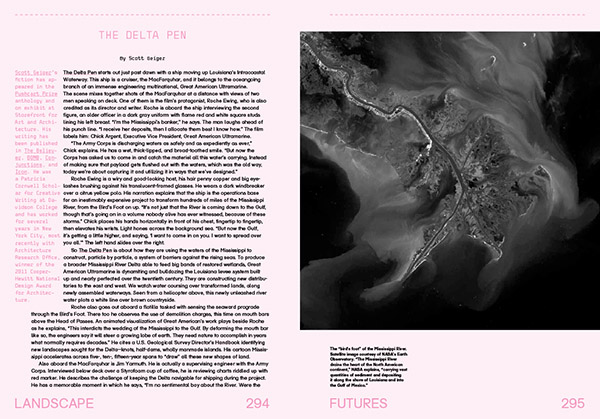

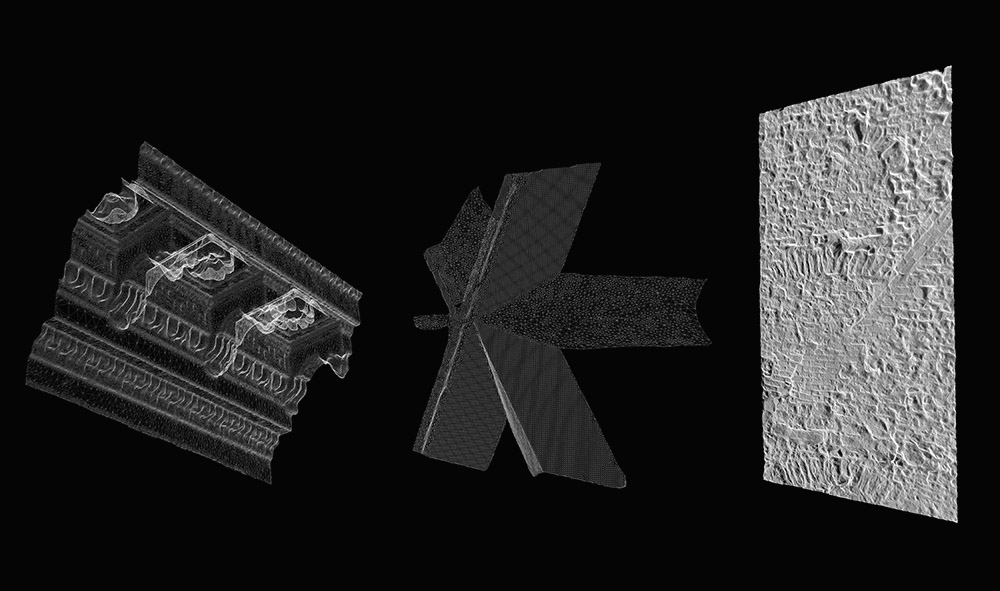

[Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Scans of a

[Image: Scans of a

[Image: Barbed wire, via

[Image: Barbed wire, via  [Image: From a June 1902 issue of

[Image: From a June 1902 issue of

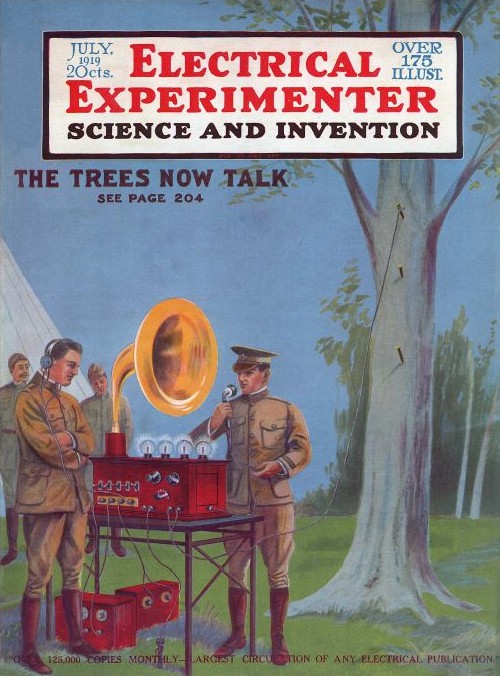

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

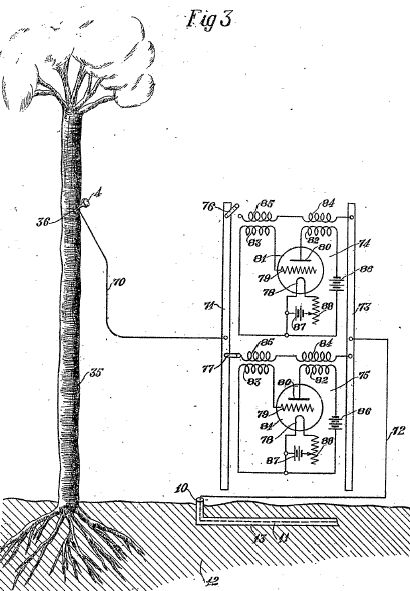

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via  [Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

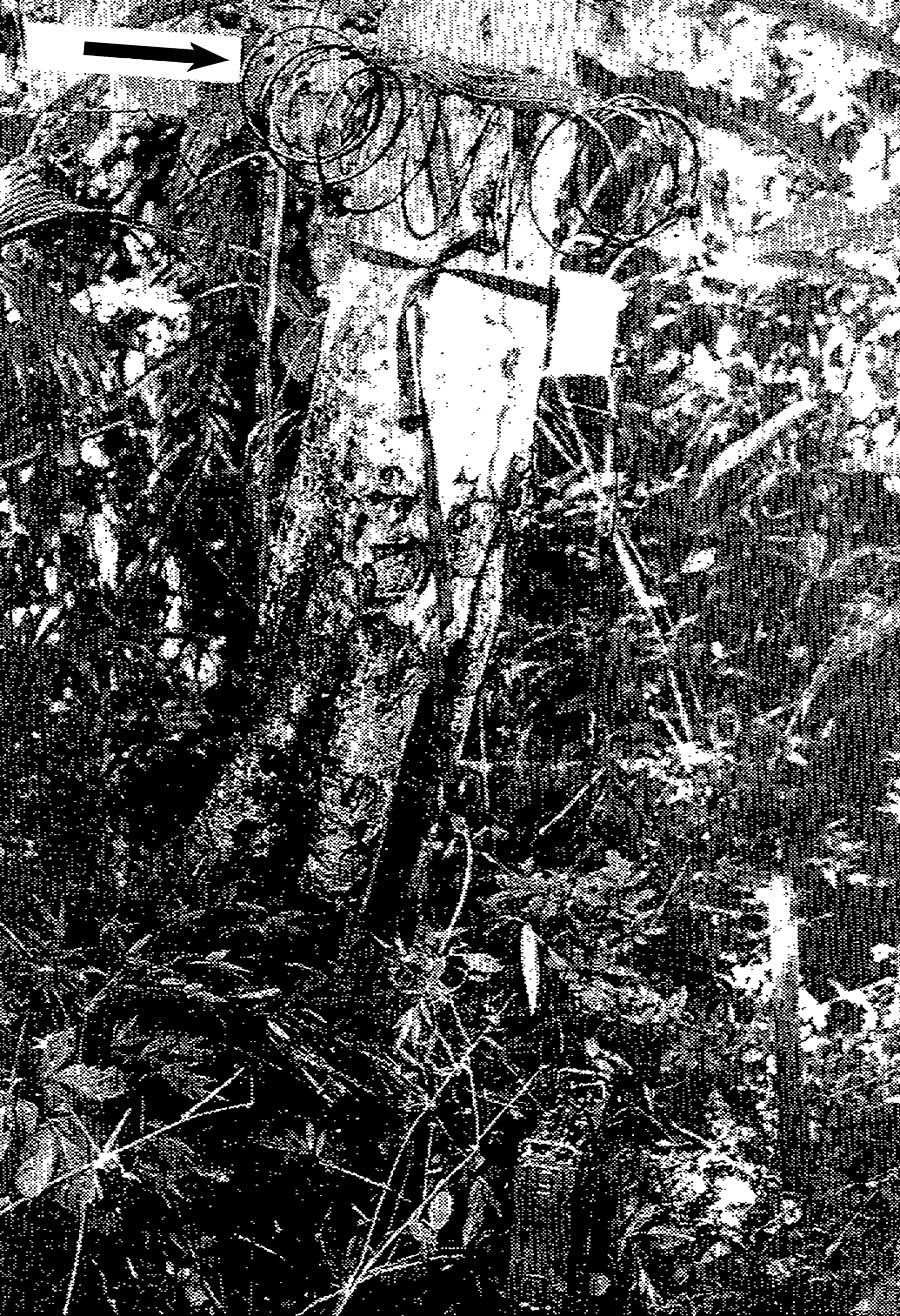

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].