Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

Every tree is a living archive, its rings a record of rainfall, temperature, atmosphere, fire, volcanic eruption, and even solar activity. These arboreal archives together reach back in time over centuries, sometimes millennia. We can even map human history through them—and onto them—tracing famines, plagues, and the passing of our own lives.

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo, with Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak in Muir Woods, outside San Francisco, where Novak points to the concentric rings of the redwood trunk and says, “Here I was born… and here I died”].

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo, with Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak in Muir Woods, outside San Francisco, where Novak points to the concentric rings of the redwood trunk and says, “Here I was born… and here I died”].

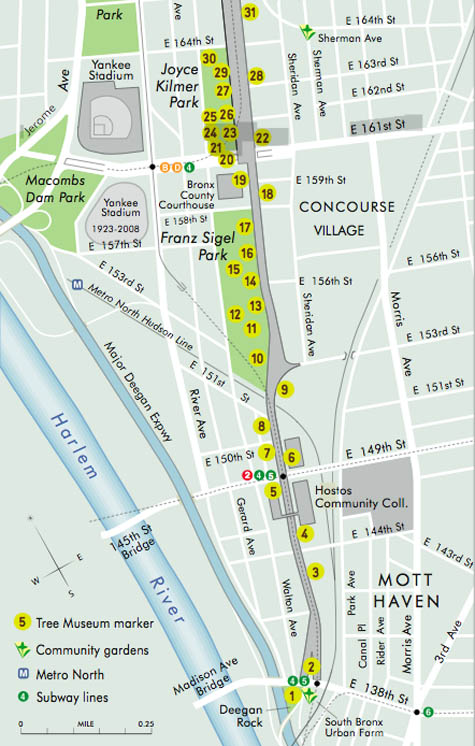

For artist Katie Holten, trees were thus the natural starting point for an oral history of a city street in the Bronx. To mark the 100th anniversary of the Grand Concourse, a four-mile-long boulevard that connects Manhattan to the parks of the Northern Bronx, Holten has created the Tree Museum: 100 specially-chosen trees between 138th Street and Mosholu Parkway, each of which has a story to tell if you dial the number at its base.

The museum opens today, June 21, with a parade and street fair: for those of us not in New York, a podcast and brochure will be available for download, and you also can view each of the tree locations on Google Maps.

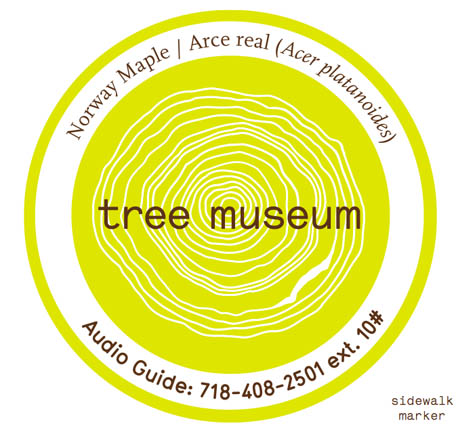

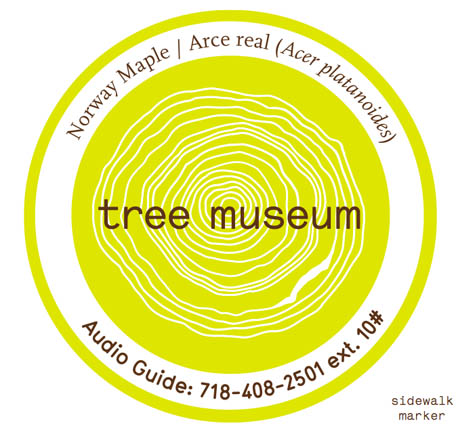

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

Only a handful of the one hundred “story-trees” date from the Concourse’s construction, when an avenue of Norwegian maples was planted to shade carriages and pedestrians strolling along the broad boulevard. In an email conversation, Holten explained to BLDGBLOG that most of these original trees were moved to Pelham Bay Park when the B/D subway line was built in the early ’30s. Twelve of the surviving maples are joined in the Tree Museum by representatives of fifty-nine other tree species, from an Amur Corktree in Joyce Kilmer park to a Kentucky Coffeetree just south of Tremont Avenue.

In fact, each tree is carefully identified by its species name, in Spanish, English, and Latin, to draw museum visitors’ attention to their variety. Holten told me that, early on in her community outreach, she realized how important naming the trees would be when a teacher in a local school confessed, incredibly, that it was only after he heard about the Tree Museum idea that “he noticed the next time he was walking that there were different kinds of trees. Before that he’d thought they were just ‘trees’.”

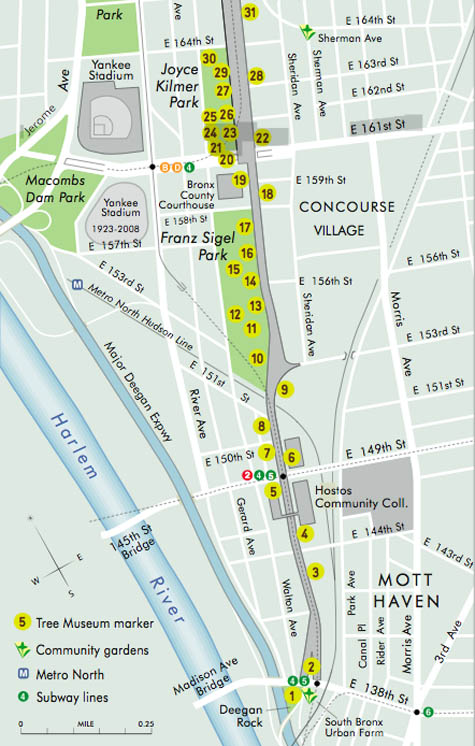

[Image: A section of the Tree Museum map; a much larger version can be seen here].

[Image: A section of the Tree Museum map; a much larger version can be seen here].

The trees were chosen for their variety, Holten says, but also for “location, age, and connection to a particular person or story.” Holten acted as matchmaker, pairing trees with former and current Bronx residents, as well as scientists, authors, and activists who have worked in the area. Among the 100 participants are well-known former Bronxites DJ Jazzy Jay and Daniel Libeskind, students at the Bronx Writing Academy, and Jonathan Pywell, Bronx Senior Forester, who helped Holten identify all the trees (not an easy task in mid-winter). Each has used their tree as the starting point for a personal anecdote, snippet of neighborhood history, song, or even a digital sound recording.

Taken together, the tree stories are part shared history, part personal memory, part science lesson—they form what Holten describes as “the whole ecosystem of the street.”

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

In her email, Holten went into some detail describing the range of stories you can hear as you dial each tree’s extension, from the sound of a Puerto Rican tree frog (No.73, a Gingko) to a local preservationist describing how he fought to turn an abandoned lot into the park that now surrounds No. 100, a Cottonwood. From her email:

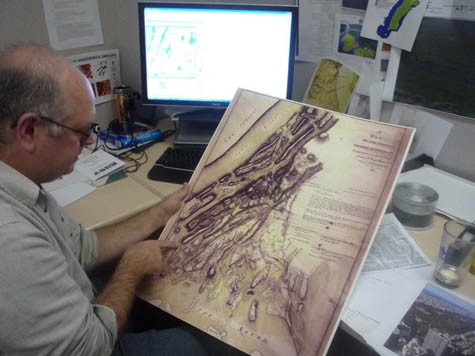

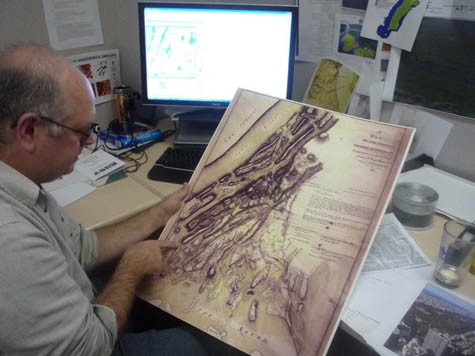

Klaus Lackner (professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Engineering at Columbia University and director of the Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy) tells the story of the carbon cycle and his attempt to create a “fake plastic tree,” or air extractor, that would suck the CO2 out of the air and convert it into something we can put in a safe place. Eric Sanderson (a landscape ecologist based at the Bronx Zoo, and author of Mannahatta) needed a really old, native tree to talk about projecting the landscape backwards. I gave him No. 9, a beautiful American Elm outside Cardinal Hayes High School.

At the northern end of the Concourse, at 206th St, there’s a huge chunk of rock between two buildings; it’s like the side of a cliff. I had to give the tree there, No. 95, to Sid Horenstein, a geologist who recently retired from the American Museum of Natural History. He’s able to use the rock outcrop to explain the story of what the Concourse lies above—it was built on a ridge and that’s one of the main reasons the street was constructed here, because it was elevated and offered spectacular views of the countryside all around.

And Tree No. 45, a Little Leaf Linden, has a story told by Patricia Foody, a 95-year-old Bronxite. She remembers her dad bringing her for a walk to the Concourse to visit his brother’s tree in just this location—it was one of the original maples, and many of them had plaques for soldiers who had died in World War I.

Some of the stories come from people who work with the trees directly: Jennifer Greenfeld, director of Street Tree Planting for the Parks and Recreation department, uses No. 66, a Chinese Elm, to provide an overview of street trees throughout New York City and the policy battles they sometimes cause. Barbara Barnes, a landscape architect also with the Parks department, puts her tree in the context of the historic street tree canopy project she’s working on, to replant Joyce Kilmer and Franz Sigel parks as they were originally laid out.

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

For other participants, the trees function as more of a backdrop for personal history and community activism. Sabrina Cardenales is the real-life model for the character Mercedes in Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx, which documents extreme urban poverty in New York: both Sabrina and Adrian introduce themselves and read a passage from the book as part of the Tree Museum. Meanwhile, Majora Carter, an environmental justice activist and MacArthur fellow from the south Bronx, uses tree No. 6, a honey locust, to tell people: “You don’t have to leave your neighborhood to live in a better one, and trees are an important part of making that happen.”

The variety of voices and stories Holten describes accumulate into a sense that plenty of people really do care about these trees, this street, and the Bronx in general. They also act as a series of nudges to look at the urban landscape in a new light. The result is that the Tree Museum, at least in theory, will recreate some of the optimism of the Grand Concourse’s roots in the City Beautiful movement, while not glossing over the struggles and setbacks faced by the “Champs-Élysées of the Bronx” ever since.

[Image: The Bronx Grand Concourse, looking north from 161st Street; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: The Bronx Grand Concourse, looking north from 161st Street; photo by Katie Holten].

As part of the Concourse’s centenary celebrations, the Bronx Museum and New York’s Design Trust For Public Space are running a competition called Intersections: Grand Concourse Beyond 100, to gather new proposals for regenerating the street. Although the call for entries period is now closed, Katie Holten has set up a community forum for the Tree Museum, and clearly hopes the project will prompt action, as well as reflection.

Holten explains her most basic hope, which is that the Museum will encourage people to start using and enjoying their shared public space again:

One hundred years ago the Concourse was built for people to stroll along, under the shade of the trees, but in 2009 it takes quite an effort to get people out for a walk—hopefully we’ll get them strolling! There are a number of individuals who I met because they are interested in trees, or in “green” issues, and we’ve tried to use the momentum of the Tree Museum to help them make differences. For example, Fernando Tirado (tree No. 88) is district manager for Bronx Community Board #7 and he’s been prompted to establish a “Greening the Concourse” project. He’s organizing summer internships for youth in the area: giving them a job and training, and at the same time actually greening the street.

Perhaps more importantly, Holten’s Tree Museum (which she describes as “practically invisible—it’s part of the urban fabric”) demonstrates an intriguing way to re-imagine the landscape: finding ways to make the hidden layers and connections of a street’s story visible (or audible) might ultimately be as, if not more, important than installing a new swing set in the park.

[Previous guest posts by Nicola Twilley include Watershed Down, The Water Menu, Atmospheric Intoxication, and Park Stories].

[Image: Typing messages with Katie Holten’s tree alphabet].

[Image: Typing messages with Katie Holten’s tree alphabet].

[Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in Parkfield, California, visualized by Ricky Vega].

[Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in Parkfield, California, visualized by Ricky Vega]. [Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in San Bernardino, California, visualized by Ricky Vega].

[Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in San Bernardino, California, visualized by Ricky Vega]. [Image: An otherwise unrelated diagram taken from the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated diagram taken from the  [Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in Watsonville, California, visualized by Ricky Vega].

[Image: San Andreas Fault mechanics in Watsonville, California, visualized by Ricky Vega]. [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film

[Image: A scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s film  [Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number].

[Image: Trees in the museum each have their own sidewalk marker, which gives their name and extension number]. [Image: A section of the

[Image: A section of the  [Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University].

[Image: A computer-generated image of Klaus Lackner’s prototype “synthetic tree,” which would remove carbon dioxide directly from the air; image courtesy of Columbia University]. [Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten].

[Image: Eric Sanderson pointing at a map of the Bronx; photo by Katie Holten]. [Image: The Bronx

[Image: The Bronx