[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

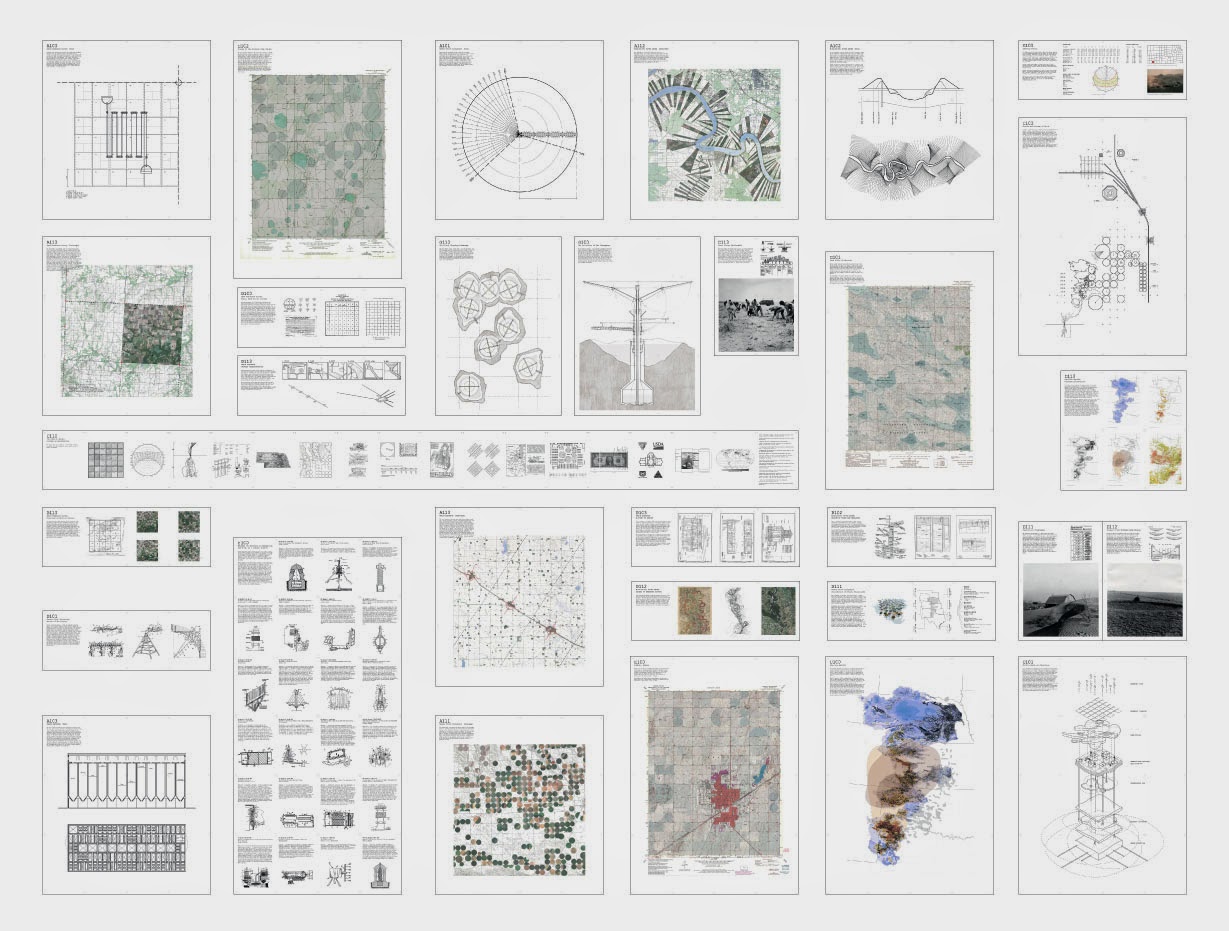

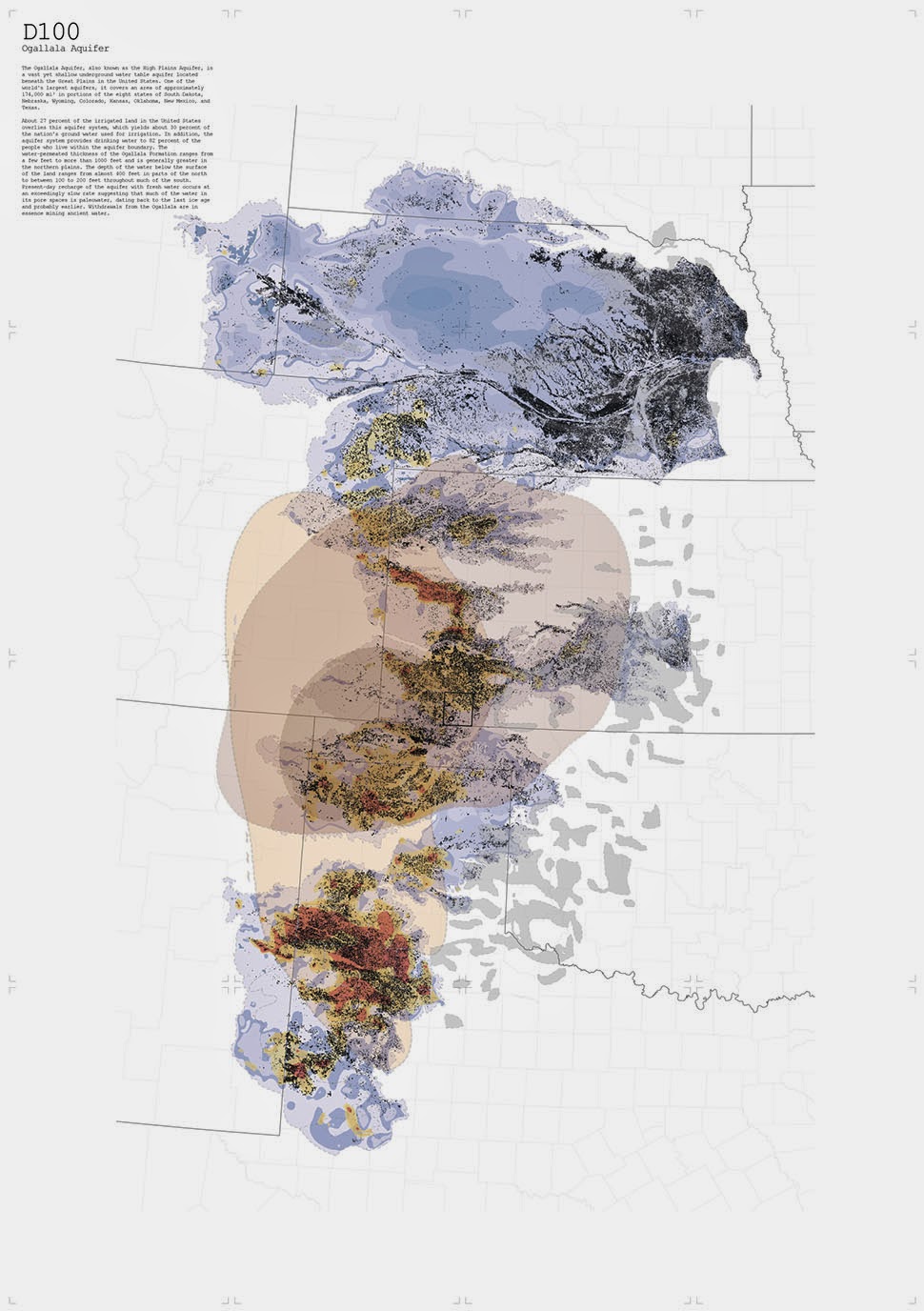

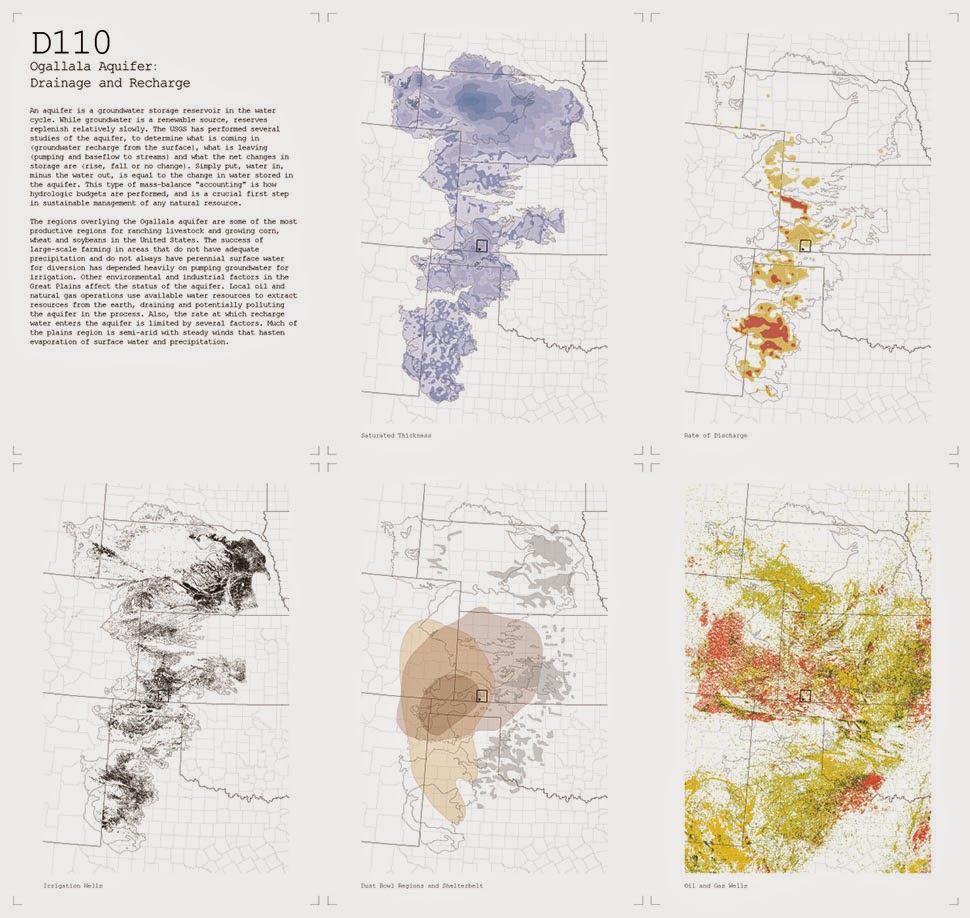

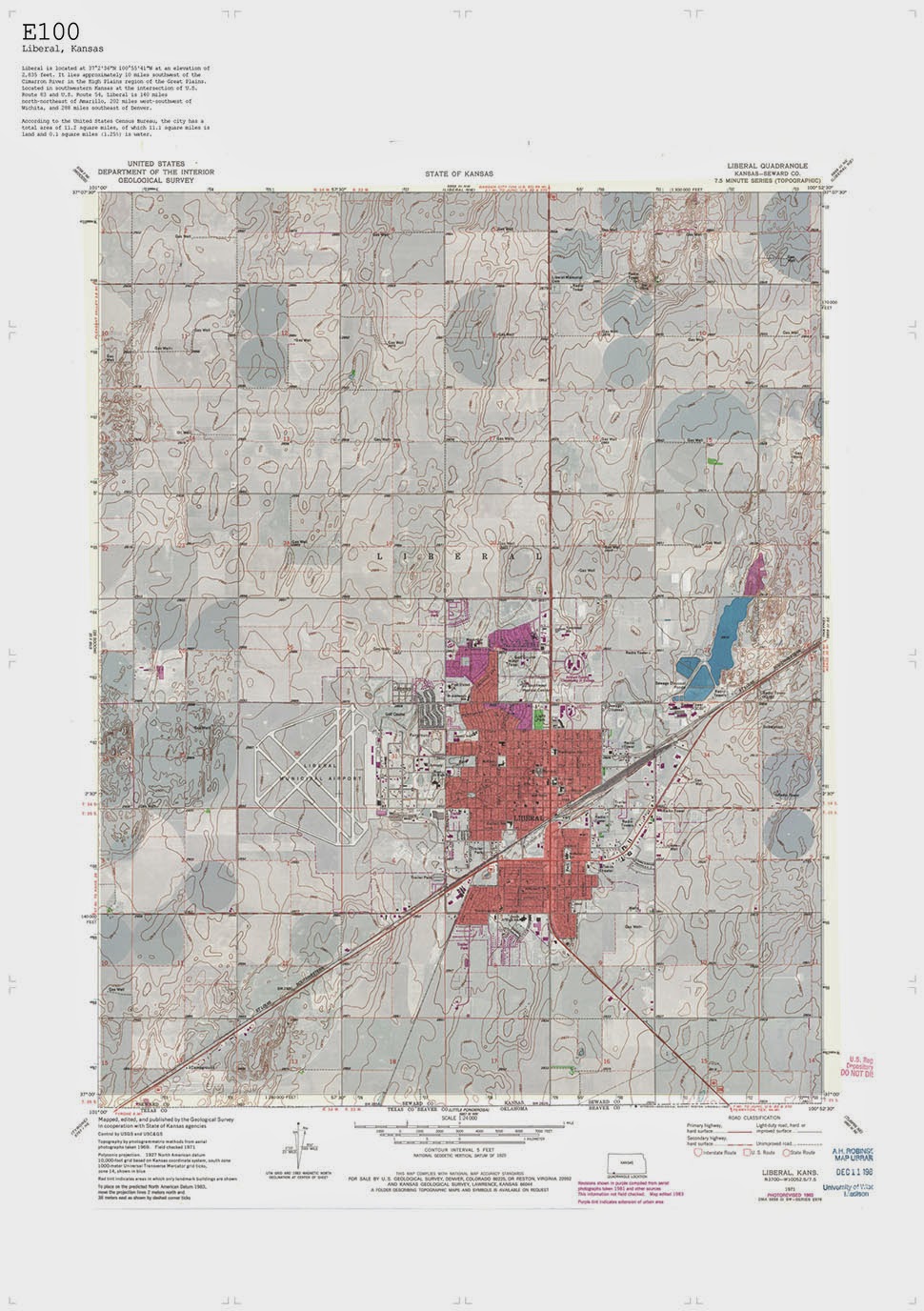

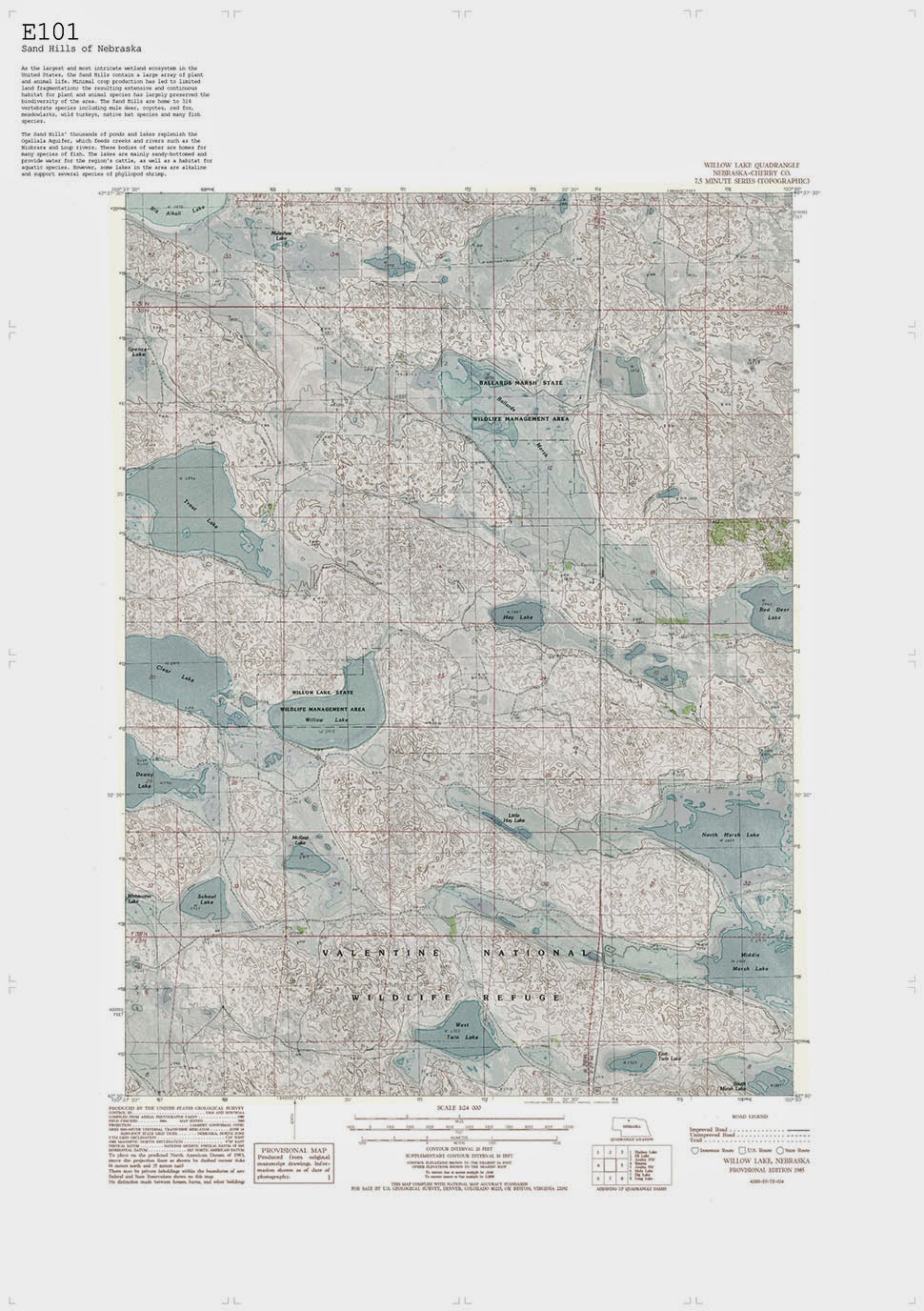

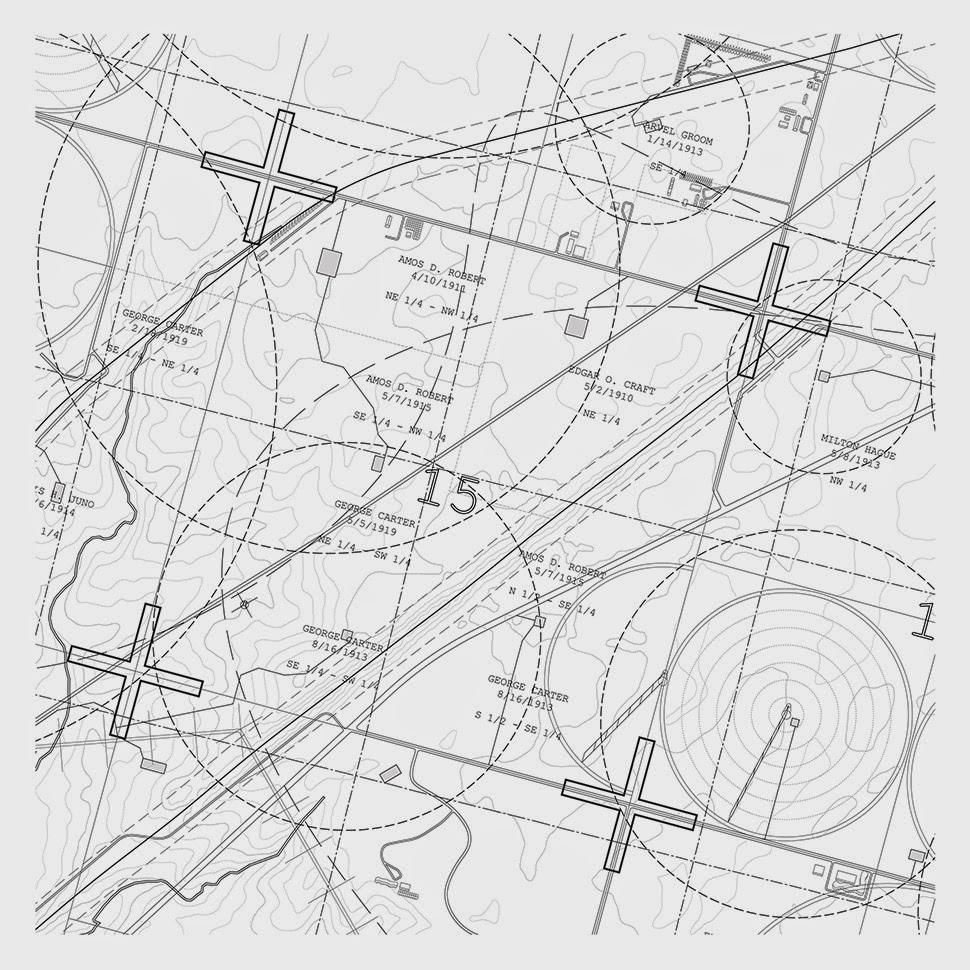

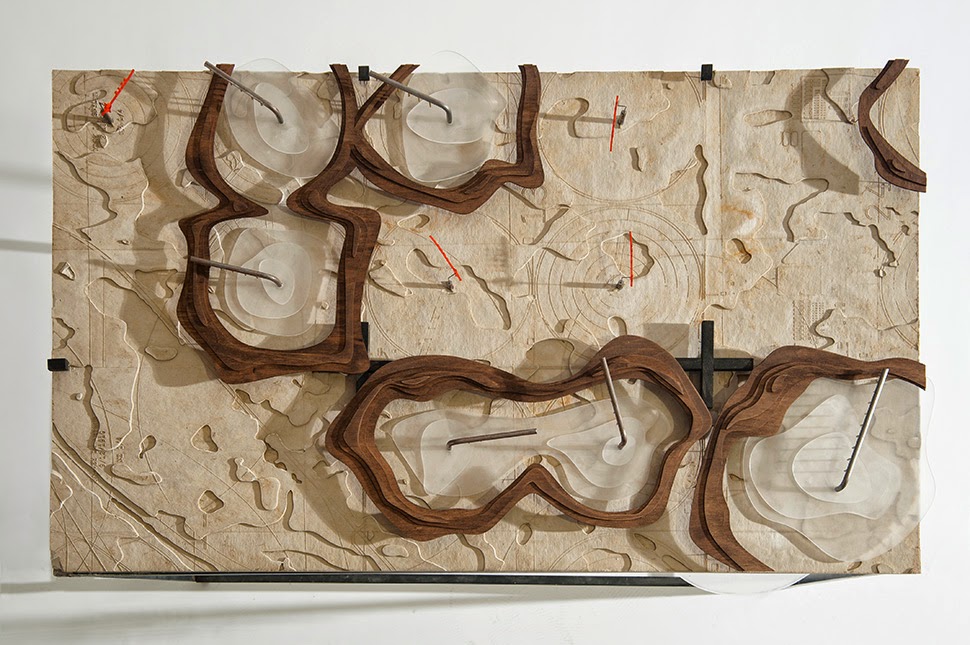

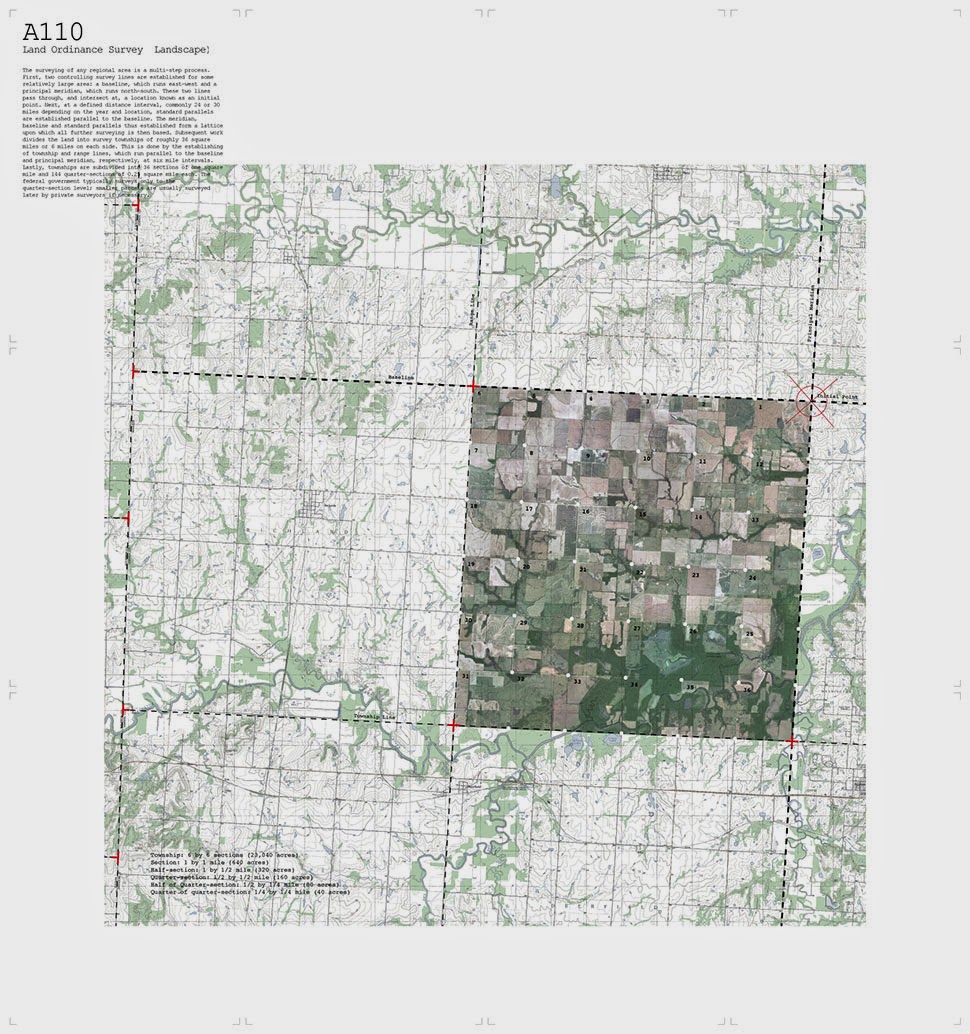

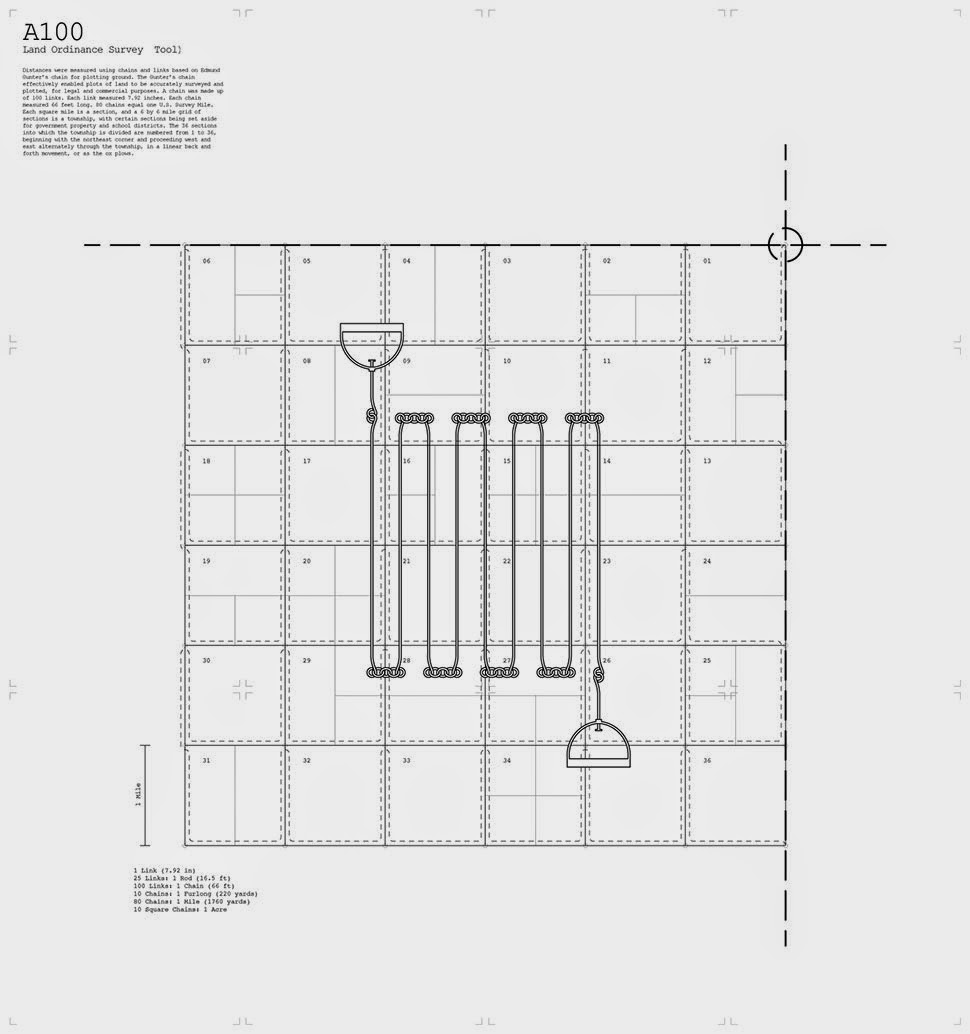

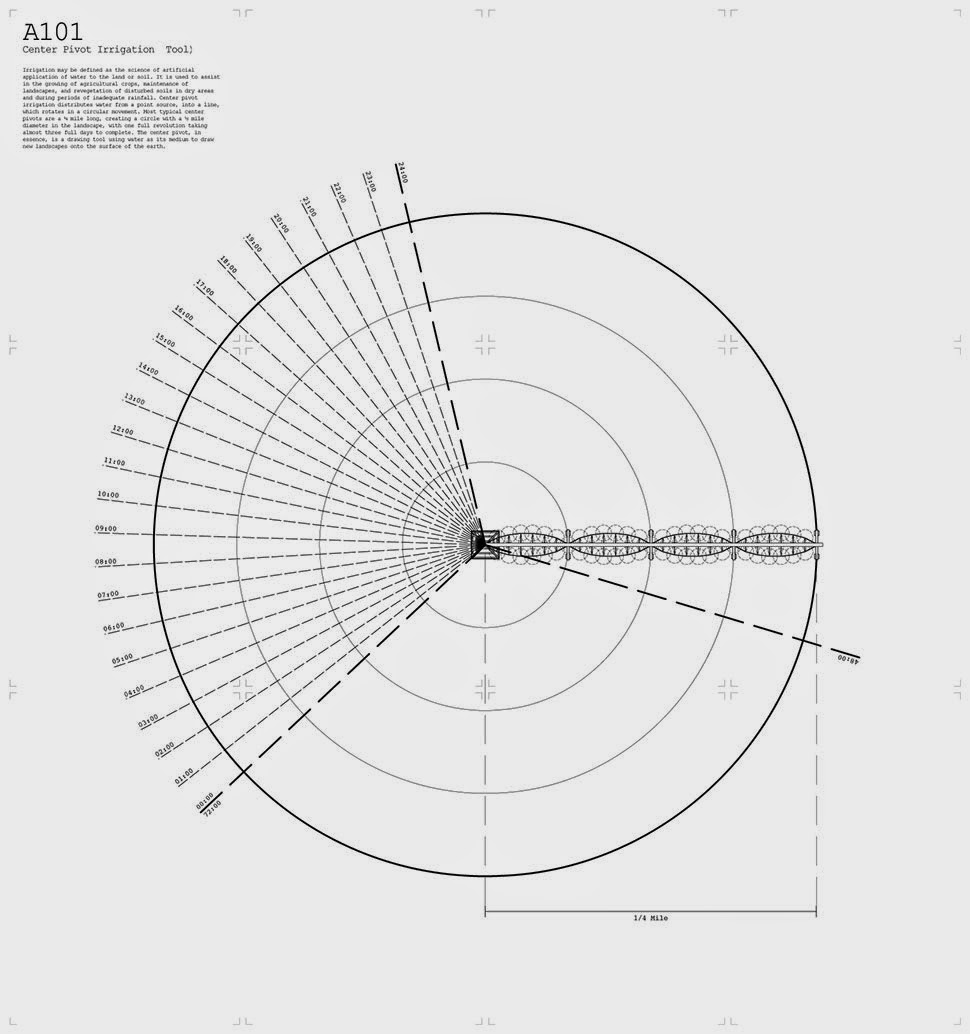

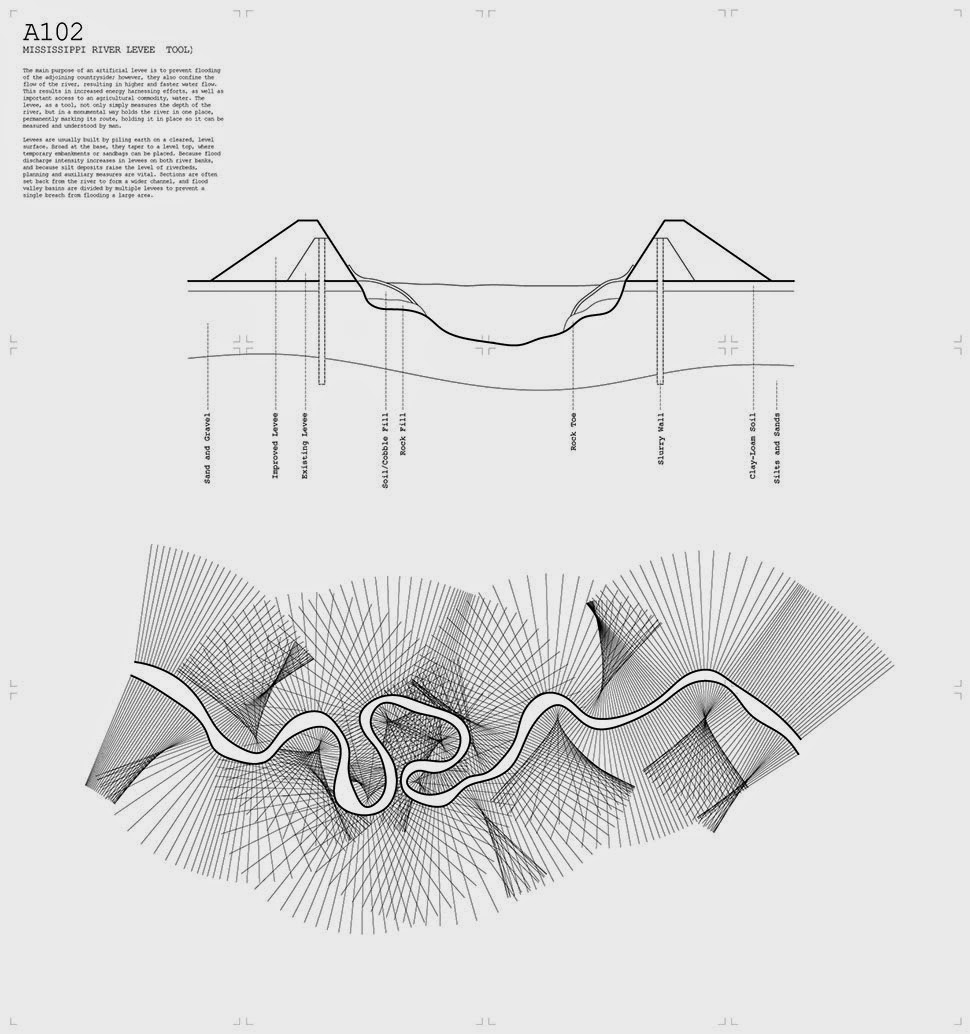

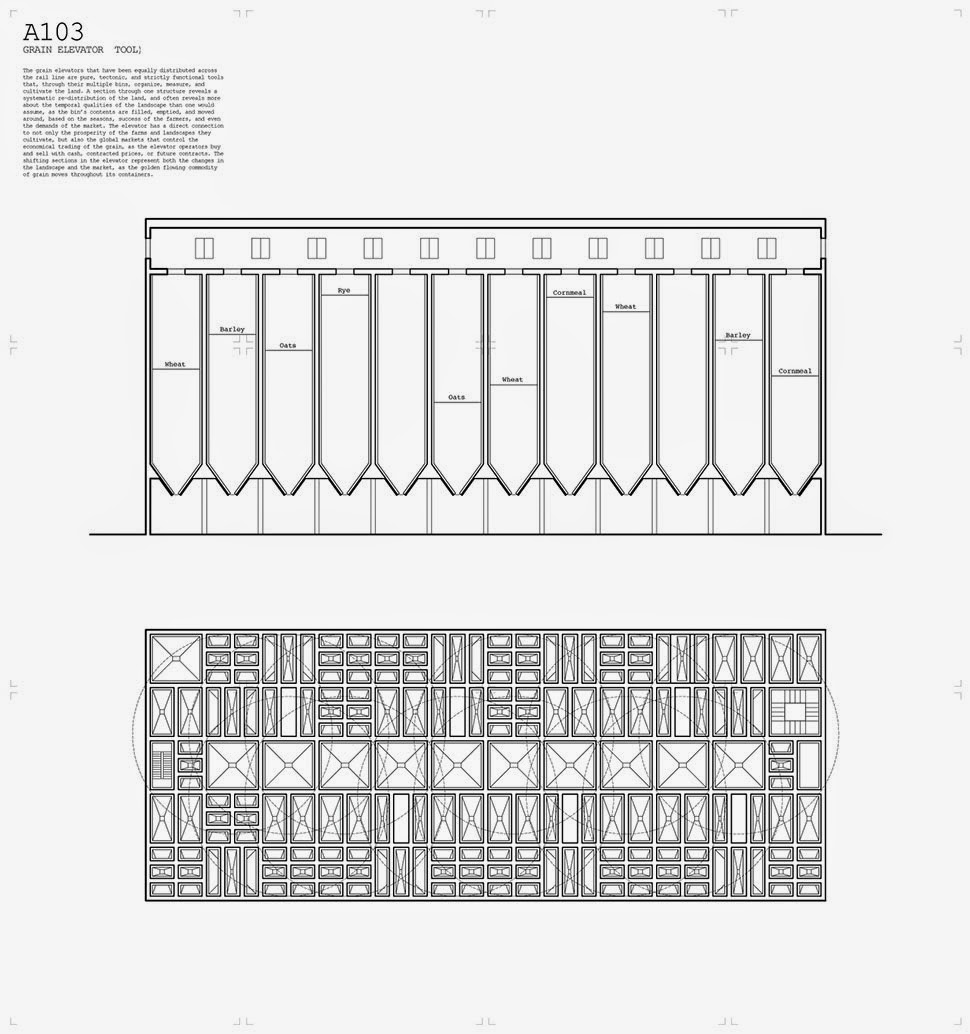

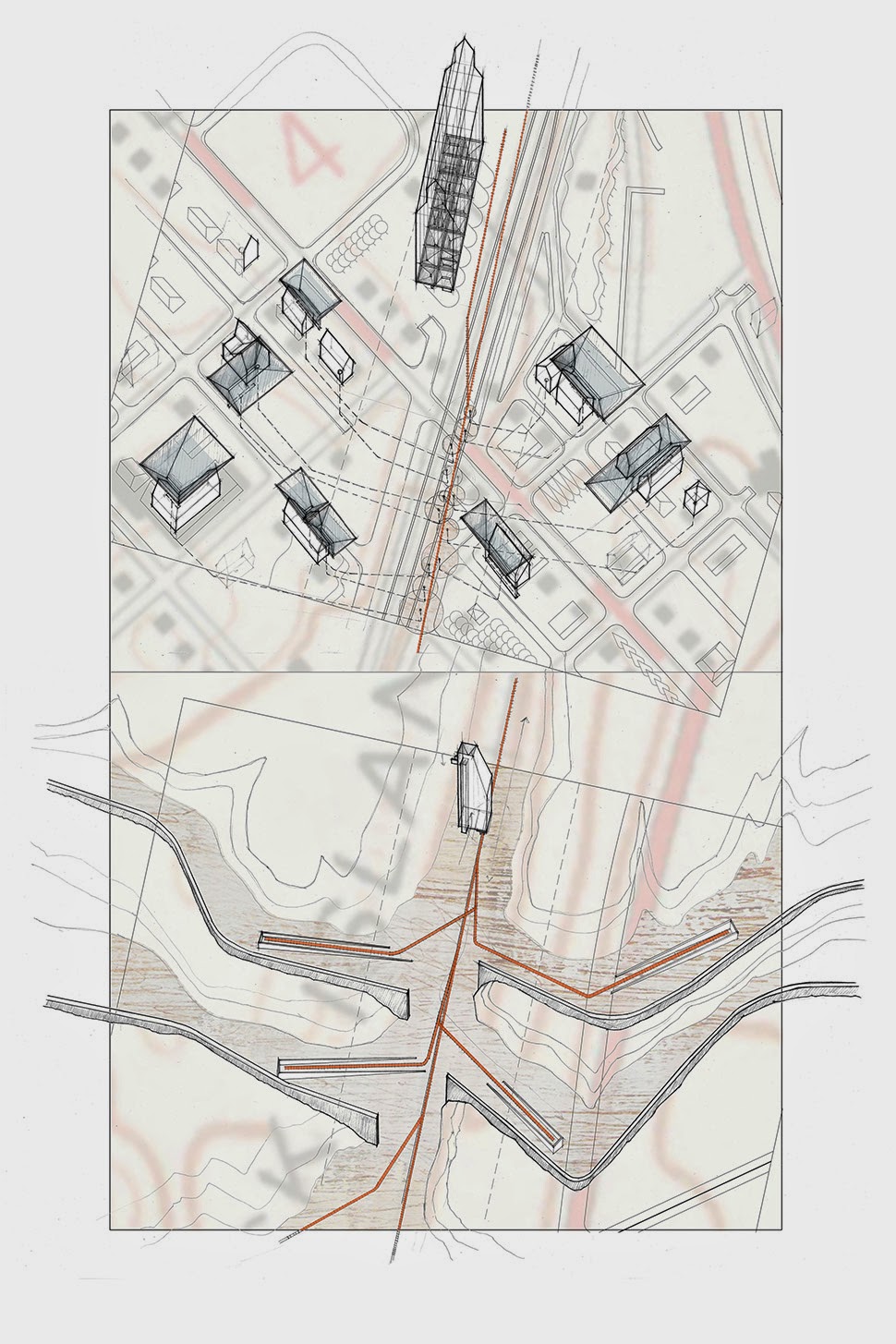

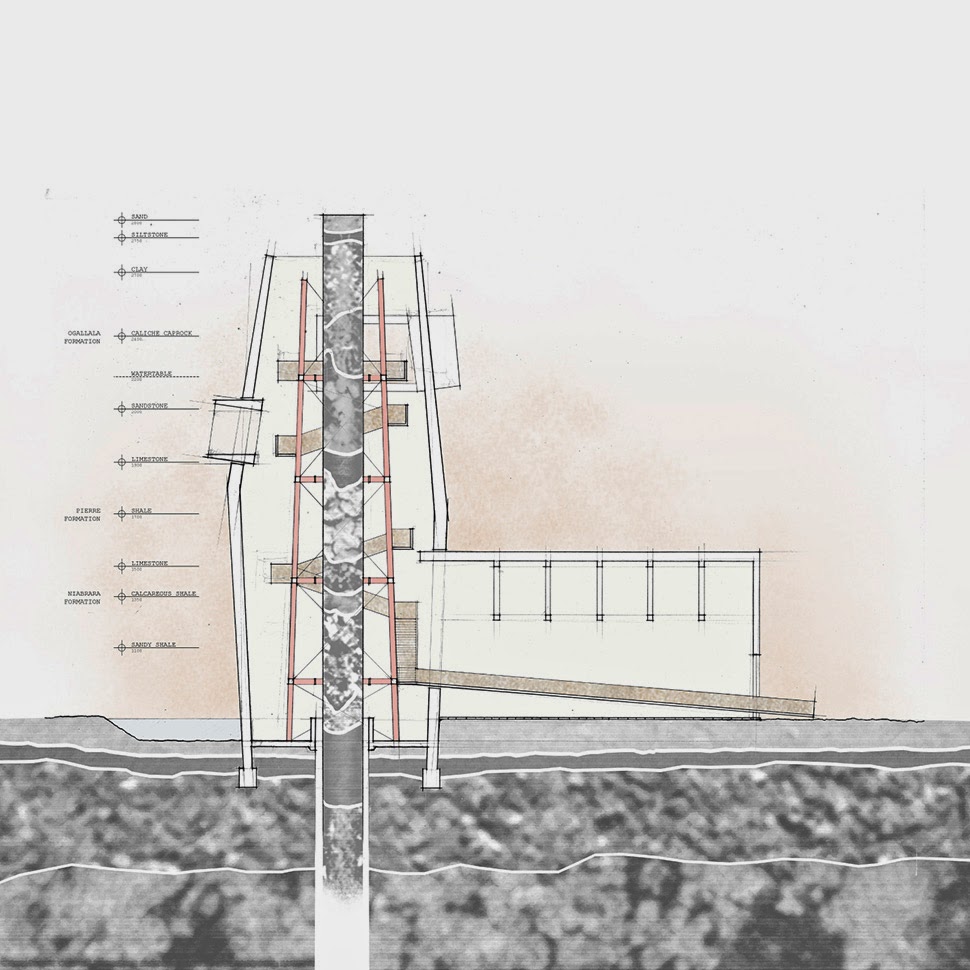

For his final thesis project at the endangered Cooper Union, Danny Wills explored how survey instruments, cartographic tools, and architecture might work together at different scales to transform tracts of land in the geographic center of the United States.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

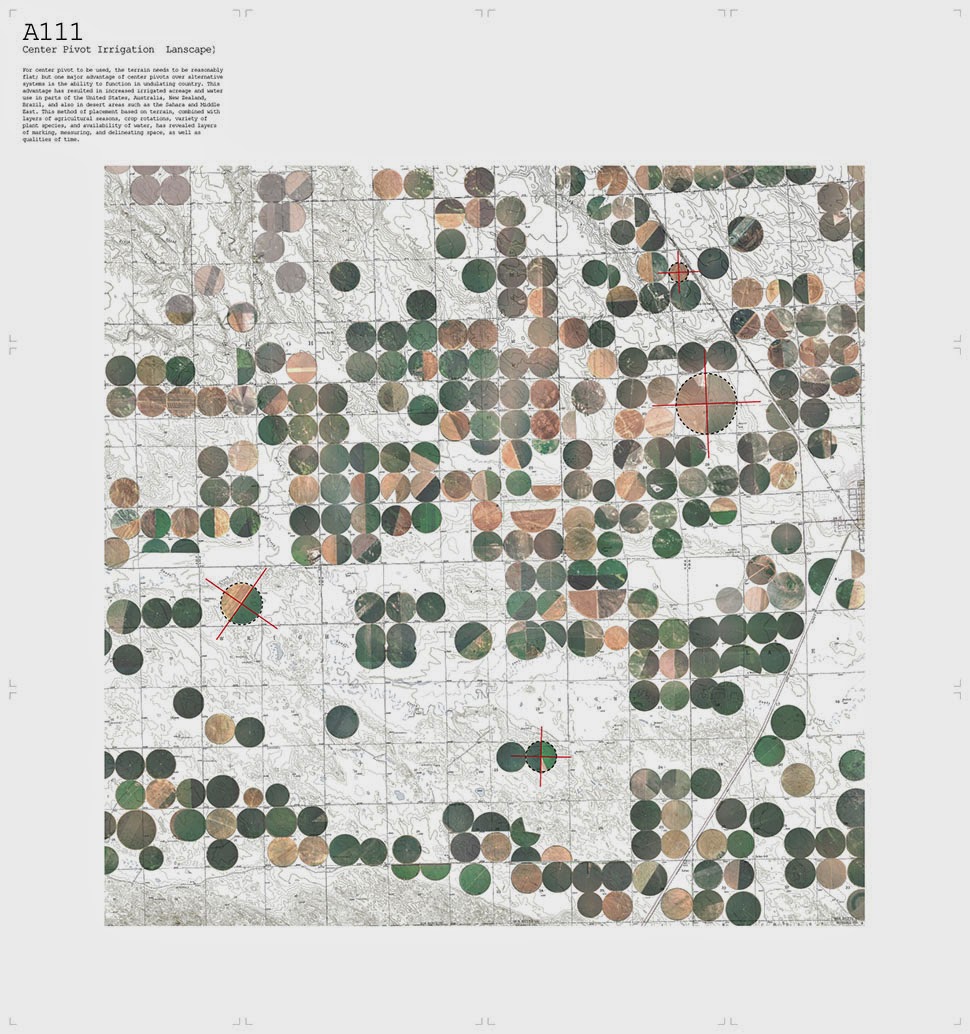

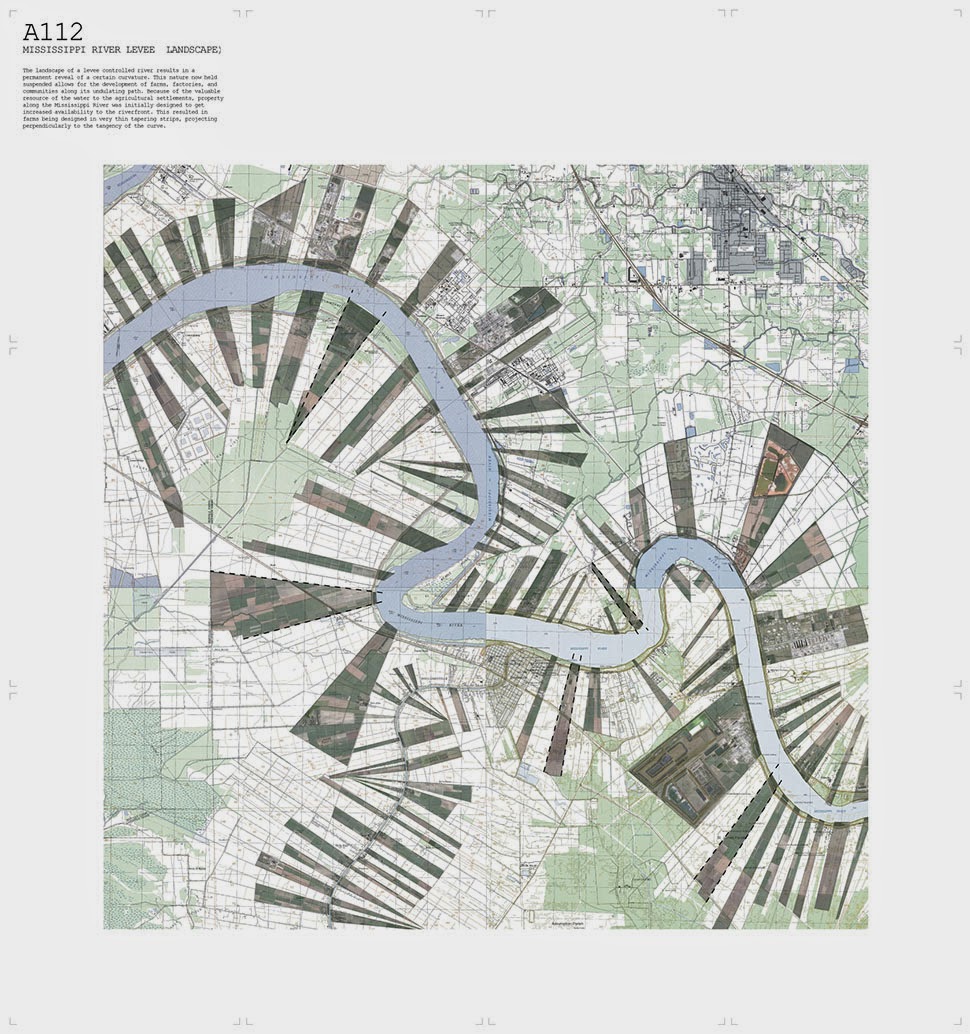

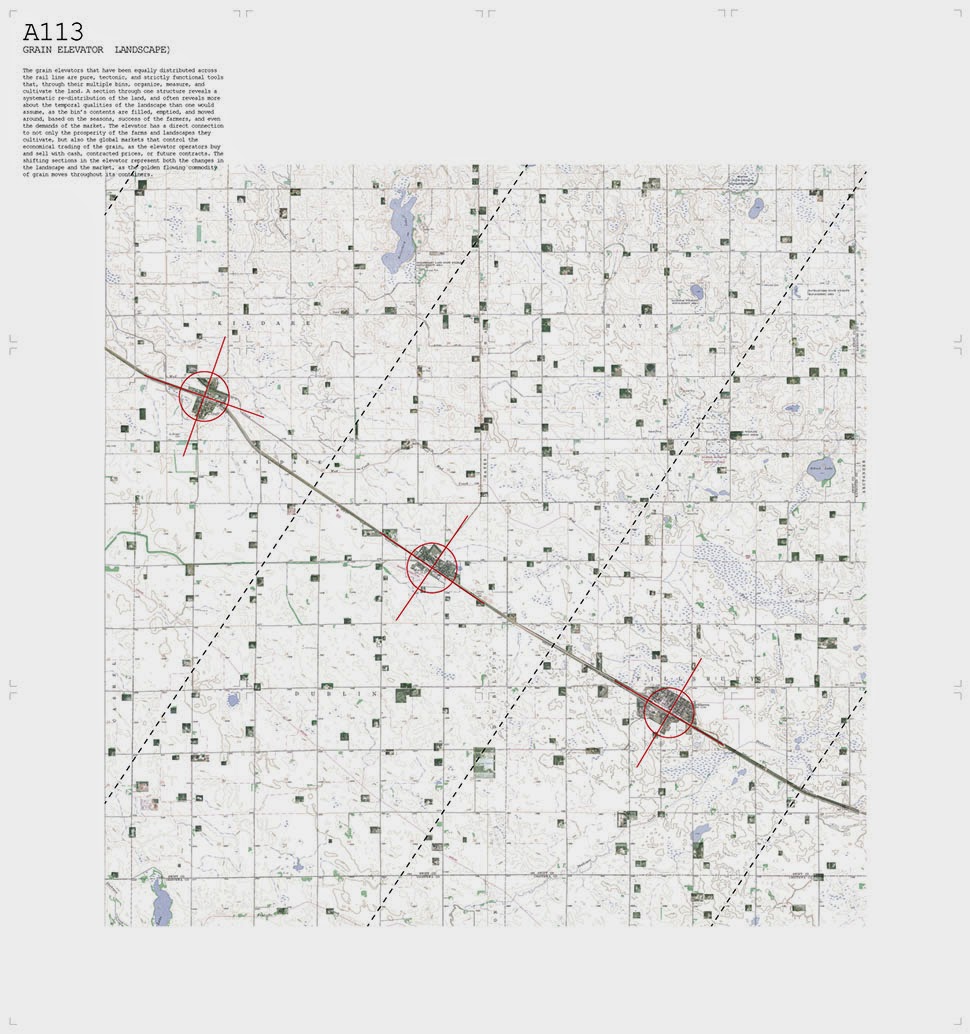

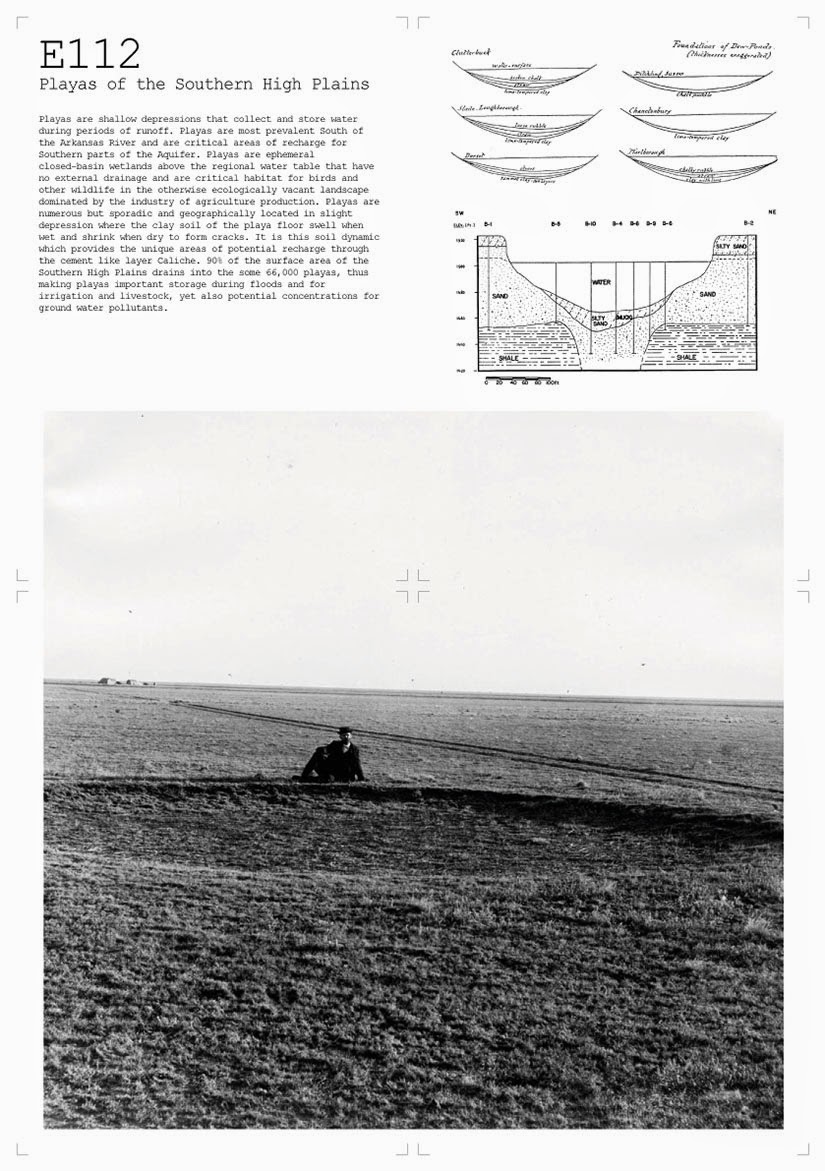

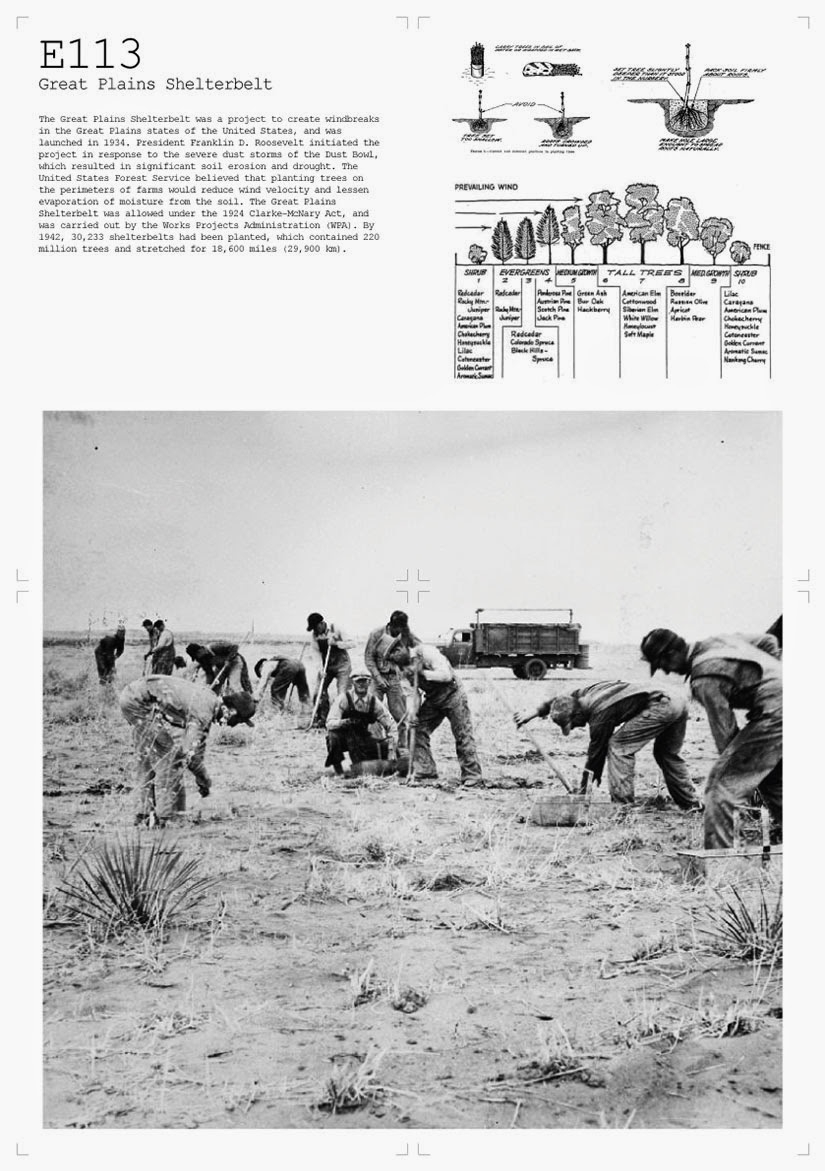

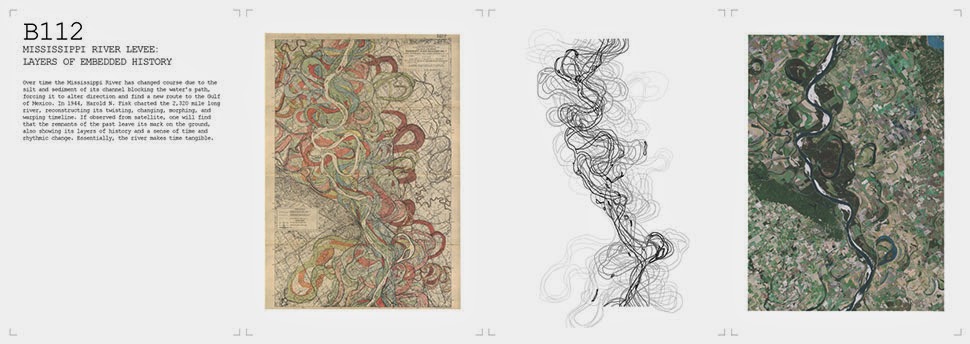

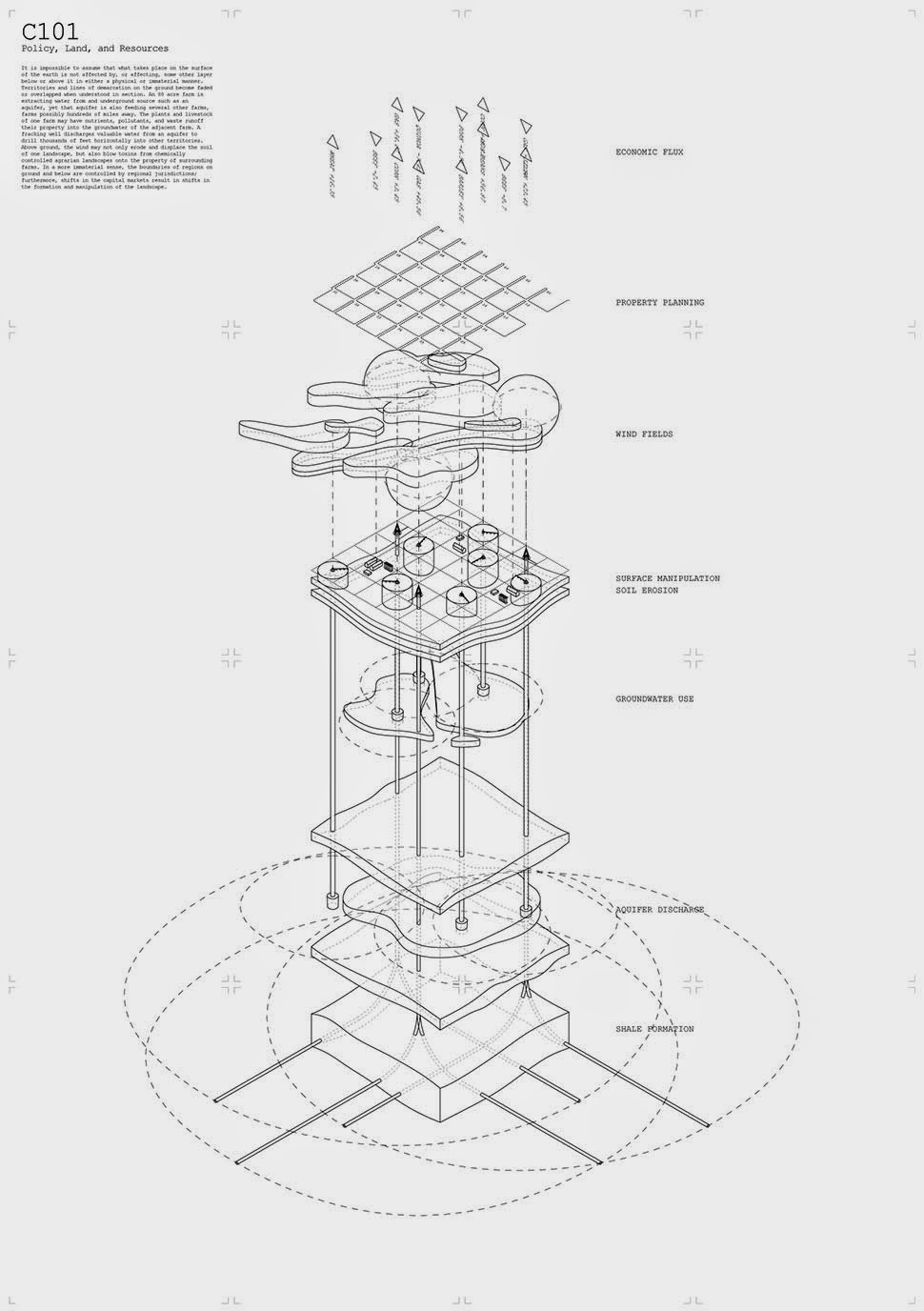

Called “Cultivating the Map,” his project is set in the gridded fields, sand hills, playas, and deep aquifers of the nation’s midland, where agricultural activity has left a variety of influential marks on the region’s landscapes and ecosystems.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

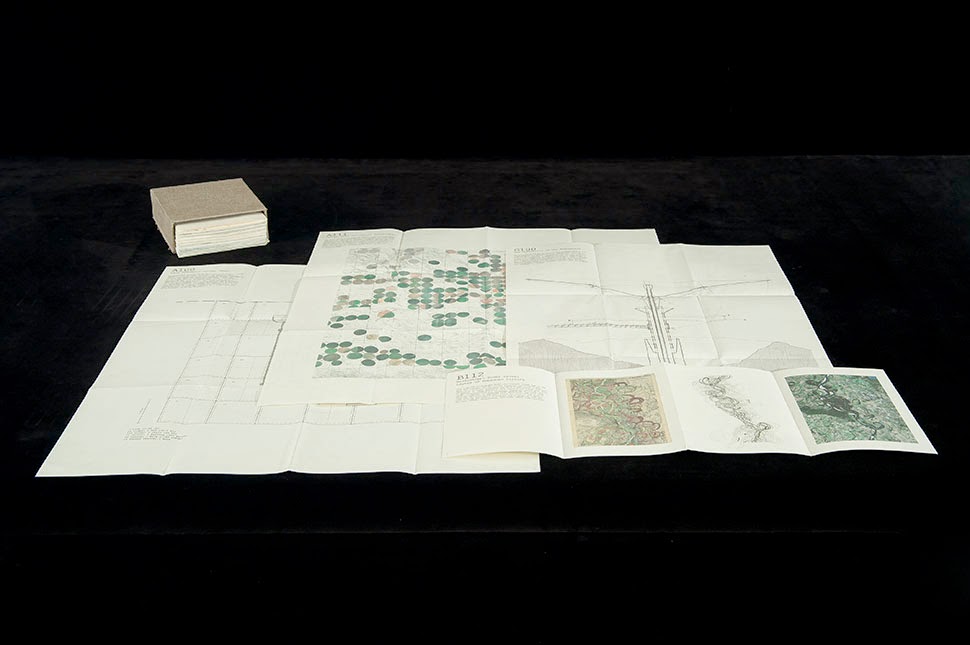

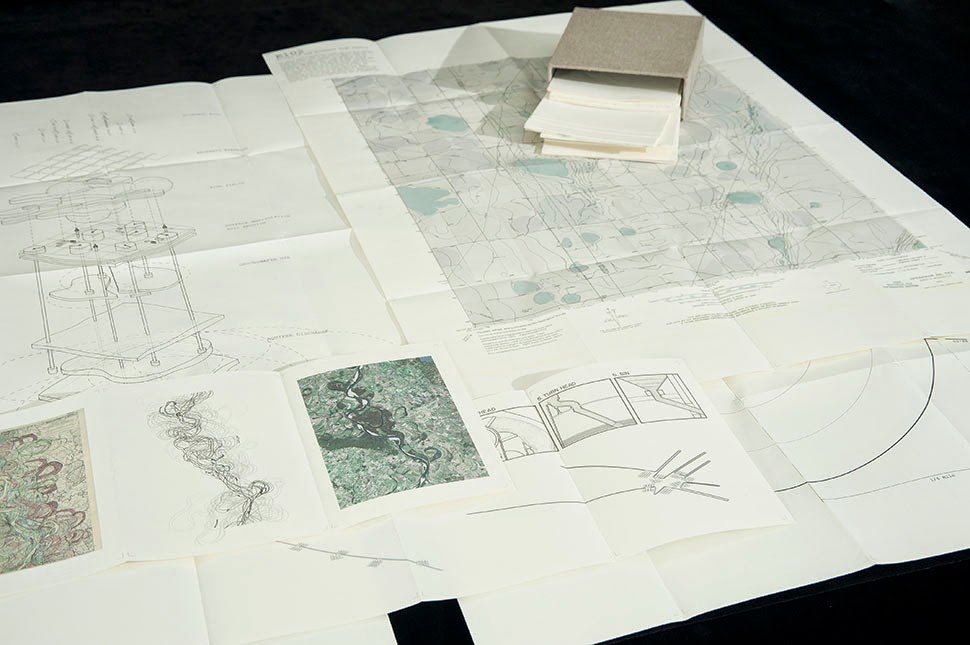

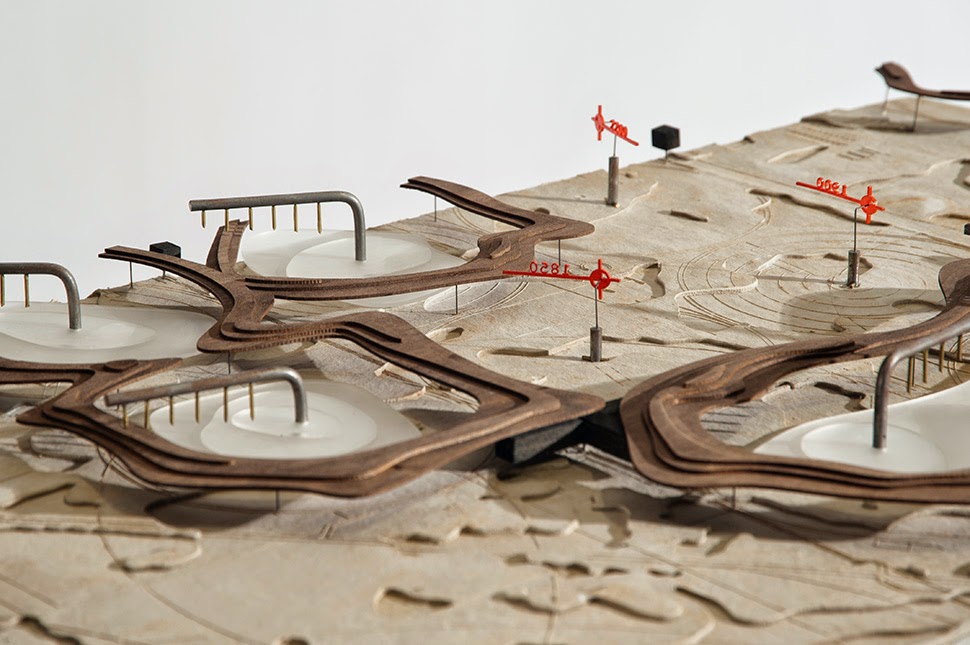

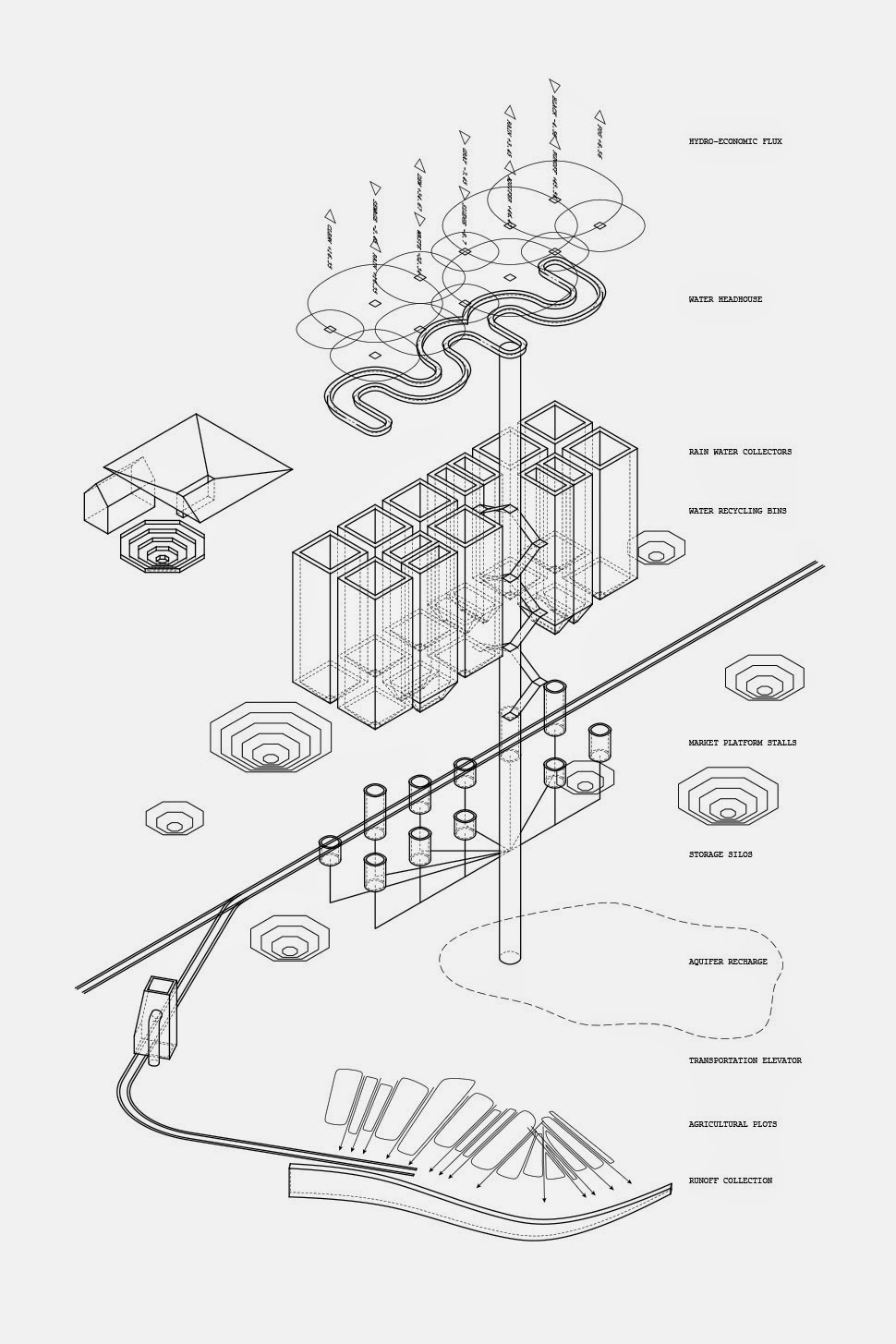

Its final presentation is light on text and heavy on models, maps, and diagrams, yet Wills still manages to communicate the complex spatial effects of very basic physical tools, how things as basic as survey grids and irrigation equipment can bring whole new regimes of territorial management into existence.

It’s as if agriculture is actually a huge mathematical empire in the middle of the country—a rigorously artificial world of furrows, grids, and seasons—dedicated to reorganizing the surface of the planet by way of relatively simple handheld tools and then rigorously perfecting the other-worldly results.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

Wills produced quite a lot of material for the project, including a cluster of table-sized landscapes that show these tools and instruments as they might be seen in the field.

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

In many ways, parts of the project bring to mind the work of Smout Allen, who also conceive of architecture as just one intermediary spatial product on a scale that goes from the most intricate of handheld mechanisms to super-sized blocks of pure infrastructure.

Imagine Augmented Landscapes transported to the Great Plains and animated by a subtext of hydrological surveying and experimental agriculture. Deep and invisible bodies of water exert slow-motion influence on the fields far above, and “architecture” is really just the medium through which these spatial effects can be cultivated, realized, and distributed.

This, it seems, is the underlying premise of Wills’s project, that architecture is like a valve through which new landscapes pass.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

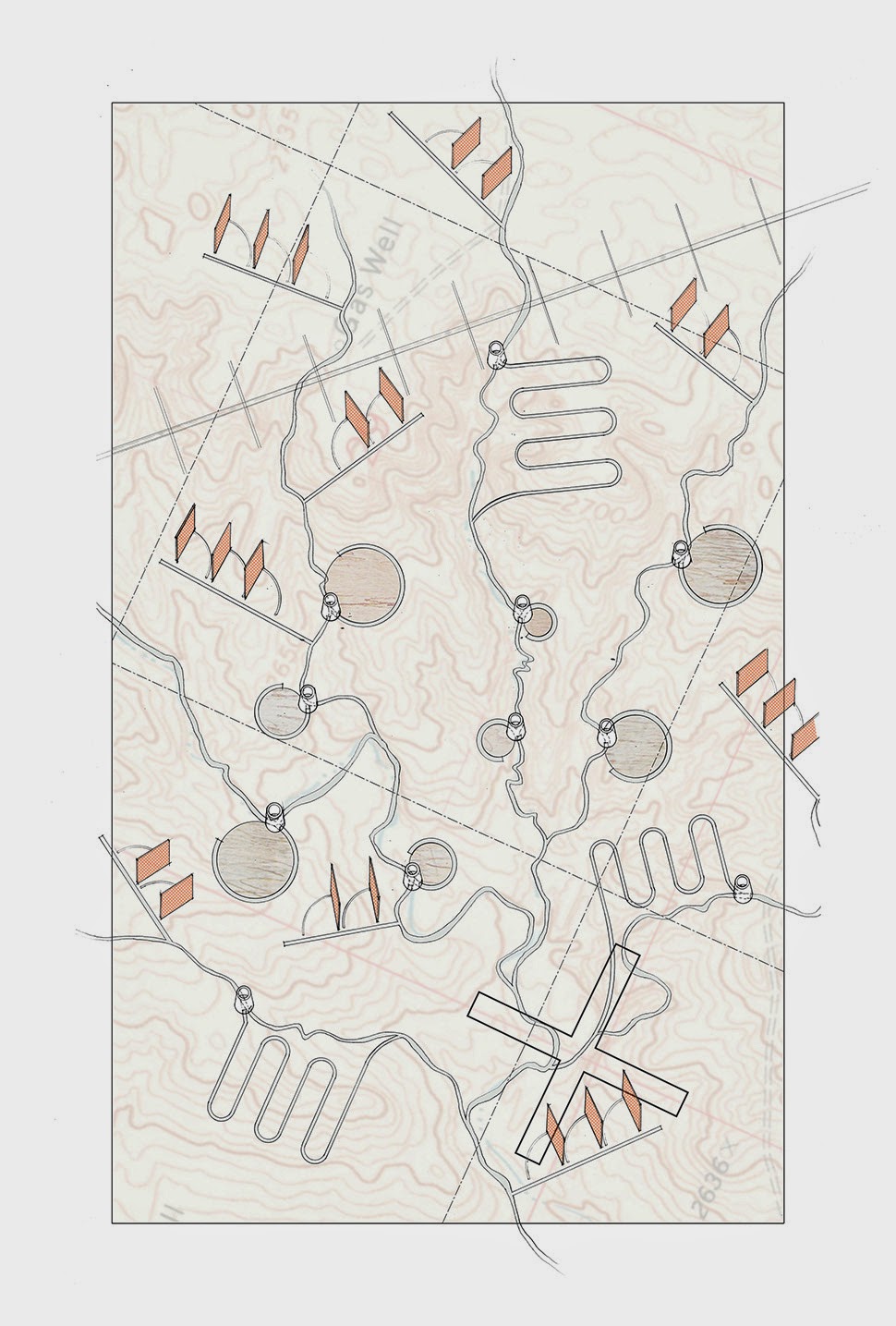

In any case, I’ve included a whole bunch of images here, broadly organized by tool or, perhaps more accurately, by cartographic idea, where the system of projection suggested by Wills’s devices have had some sort of spatial effect on the landscape in which they’re situated.

However, I’ve also been a little loose here, organizing these a bit by visual association, so it’s entirely possible that my ordering of the images has thrown off the actual narrative of the project—in which case, it’s probably best just to check out Wills’s own website if you’re interested in seeing more.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

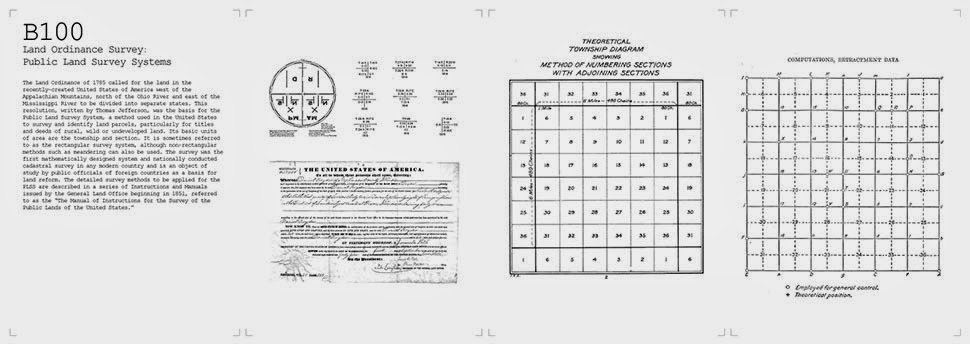

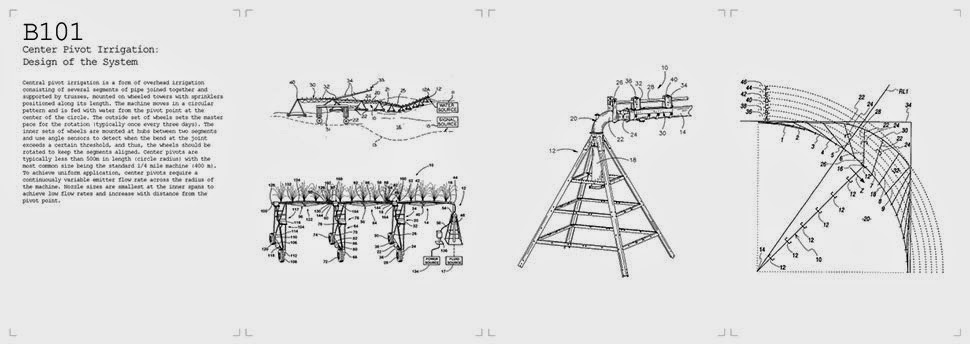

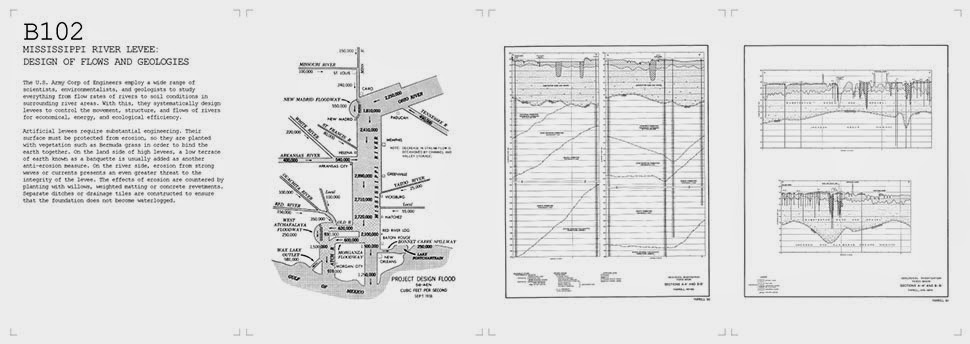

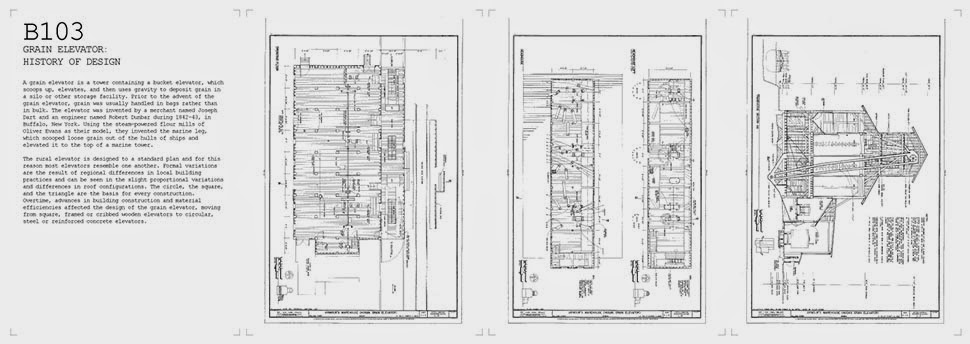

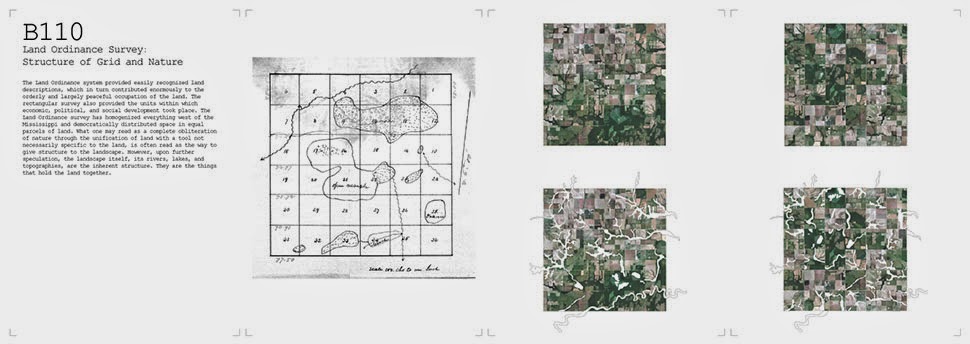

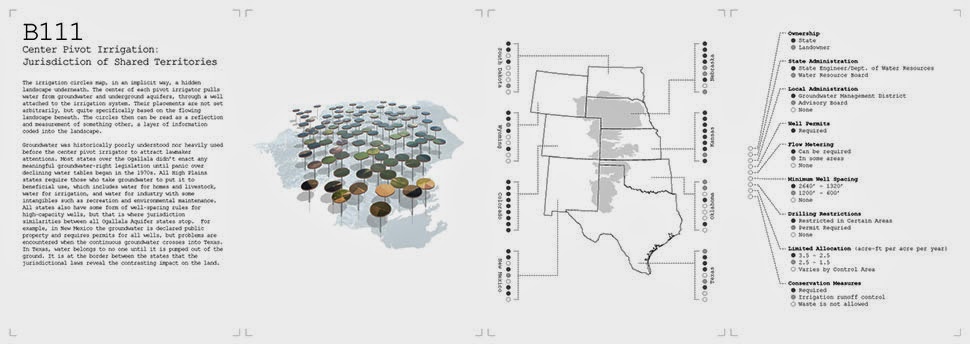

The project includes land ordinance survey tools and irrigation mechanisms, a “Mississippi River levee tool” and the building-sized “grain elevator tool.”

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

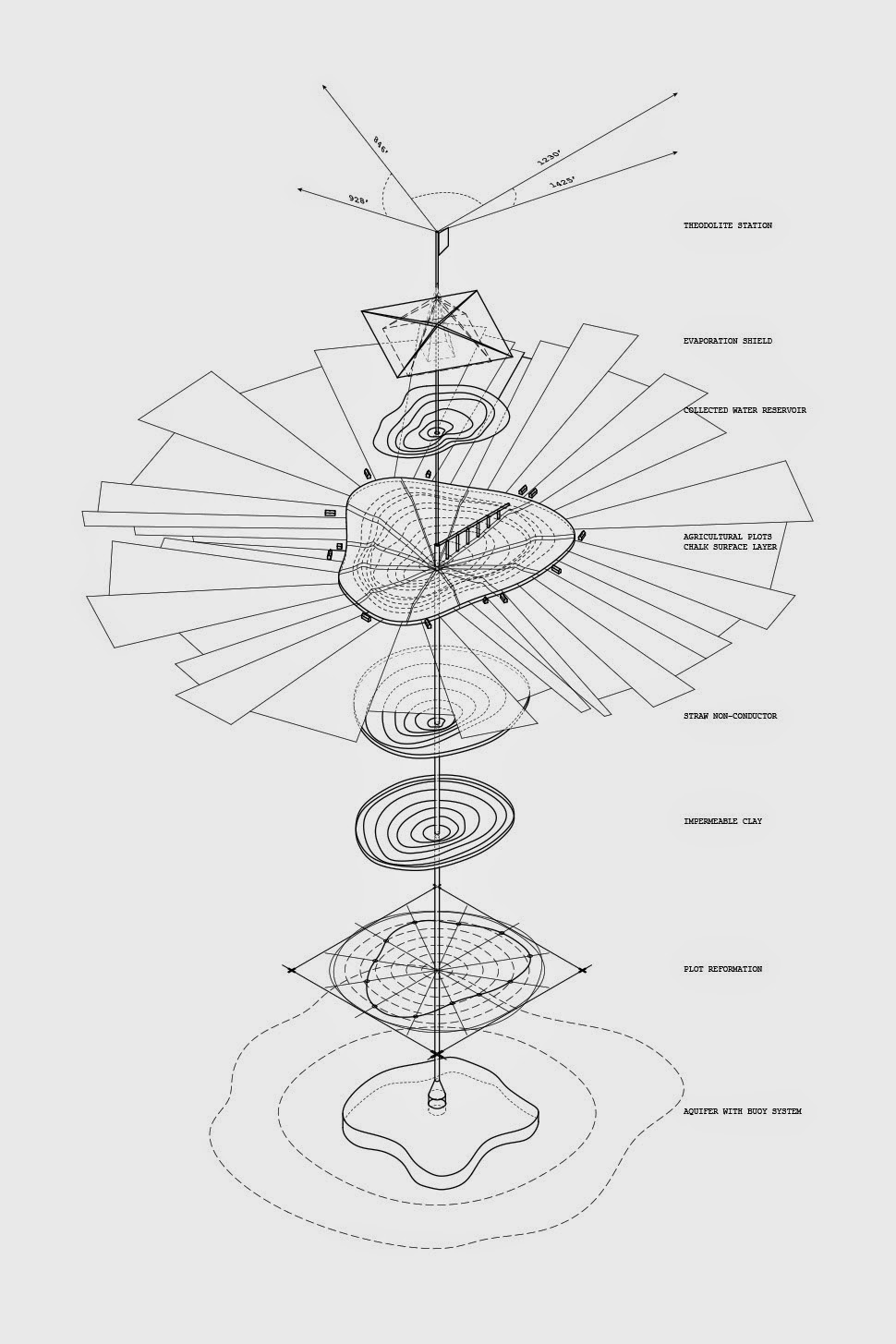

In Danny’s own words, the project “finds itself in the territory of the map, proposing that the map is also a generative tool. Using the drawing as fertile ground, this thesis attempts a predictive organization of territory through the design of four new tools for the management of natural resources in the Great Plains, a region threatened with the cumulative adverse effects of industrial farming. Each tool proposes new ways of drawing the land and acts as an instrument that reveals the landscape’s new potential.”

These “new potentials” are often presented as if in a little catalog of ideas, with sites named, located, and described, followed by a diagrammatic depiction of what Wills suggests might spatially occur there.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

The ambitious project earned Wills both the Henry Adams AIA Medal & Certificate of Merit, and the school’s Yarnell Thesis Prize in Architecture.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

I’ll wrap up here with a selection of images of the landscapes, tools, and instruments, but click over to Danny’s site for a few more. Here are also some descriptions:

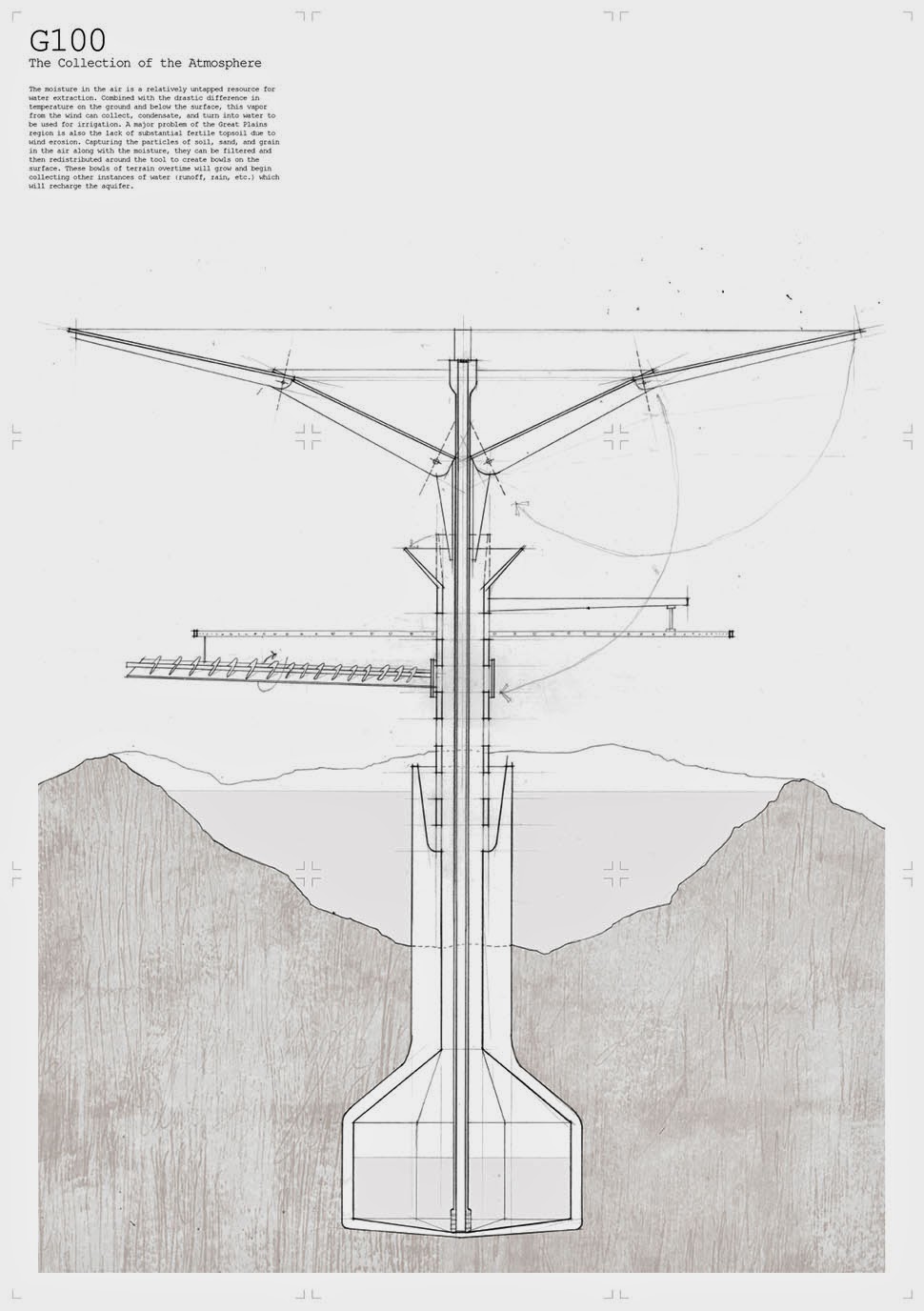

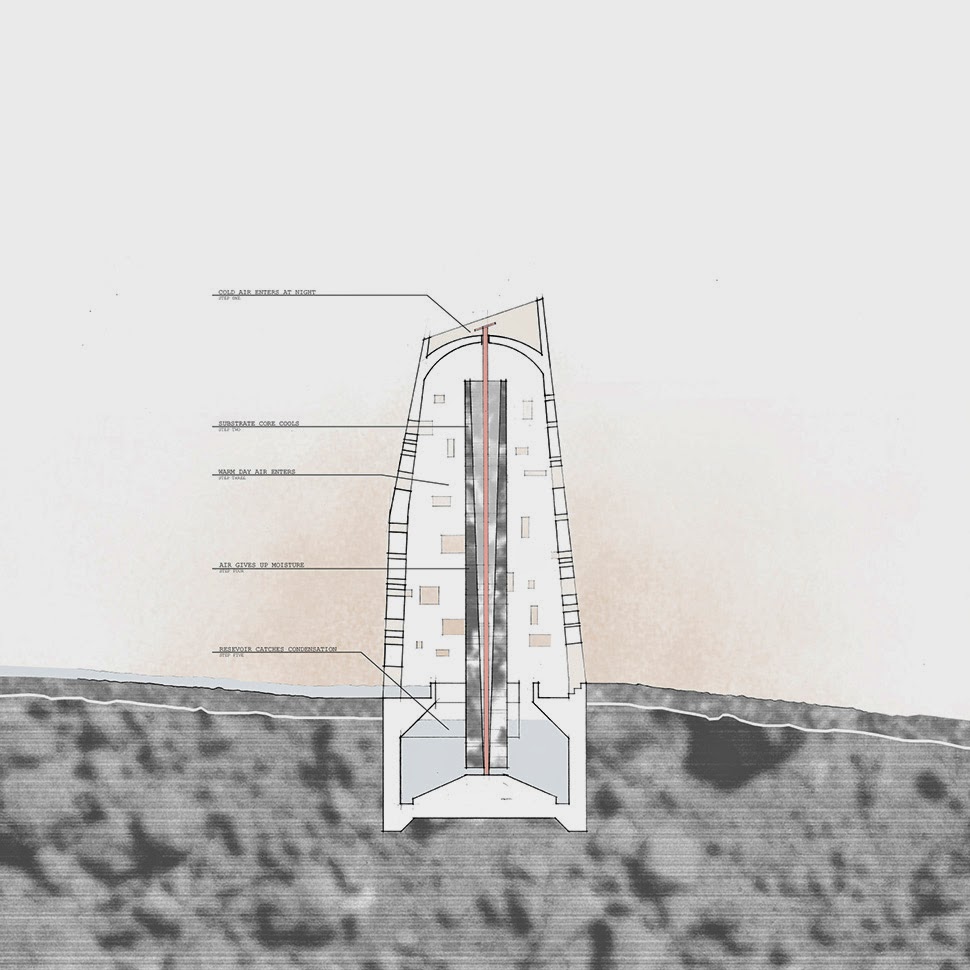

Tool 1: Meanders, Fog Fences, Air Wells

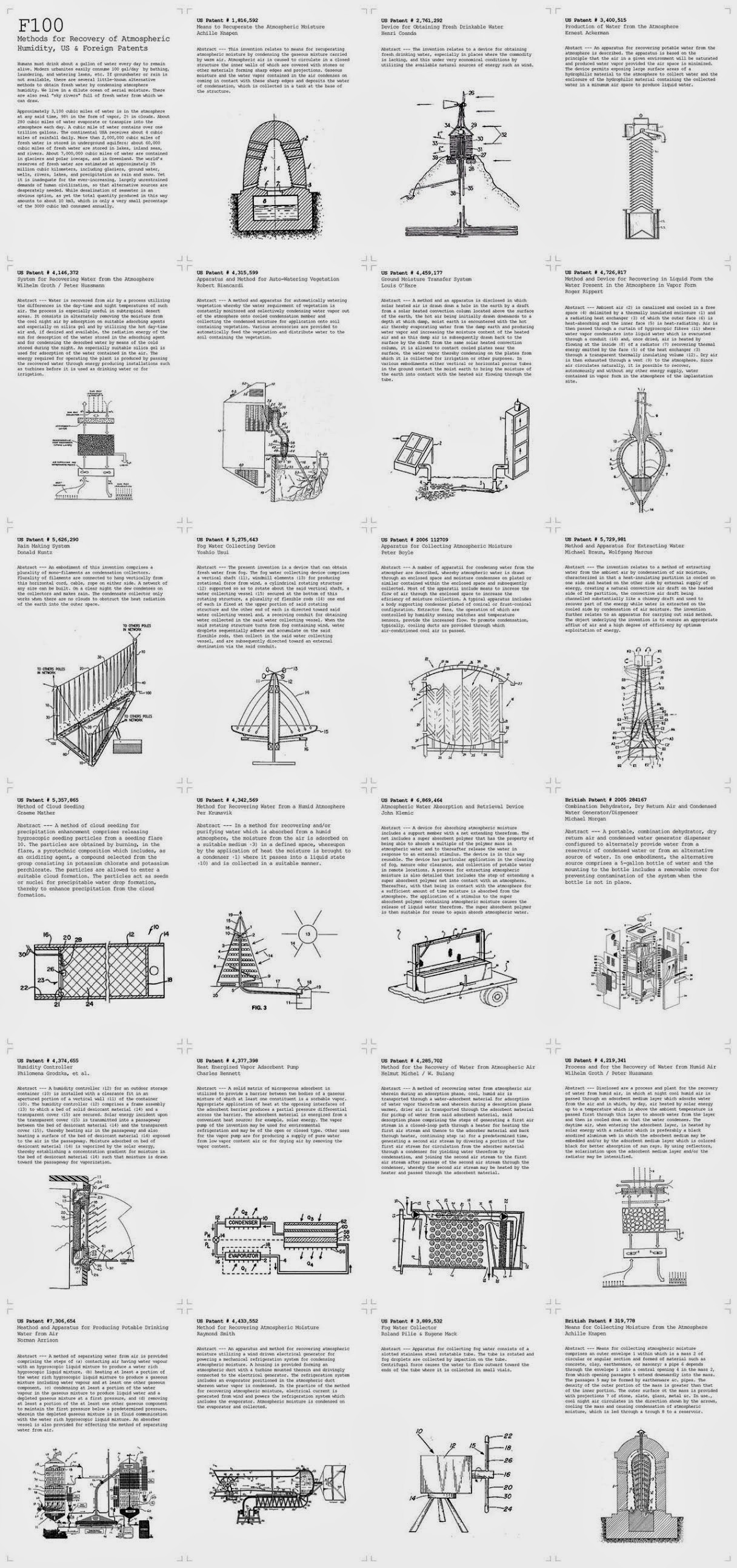

Tool 1 attaches itself to the groundwater streams, both proposing tools to redirect and slow down the flow, as well as tools to collect atmospheric water through technological systems like air wells and fog fences, forming new bodies and streams of water. The new air wells collect atmospheric water through a system of cooling and heating a substrate core inside of a ventilated exterior shell. The air wells also become spaces to observe the re-directing flow of water, as overflow quantities are appropriately managed.

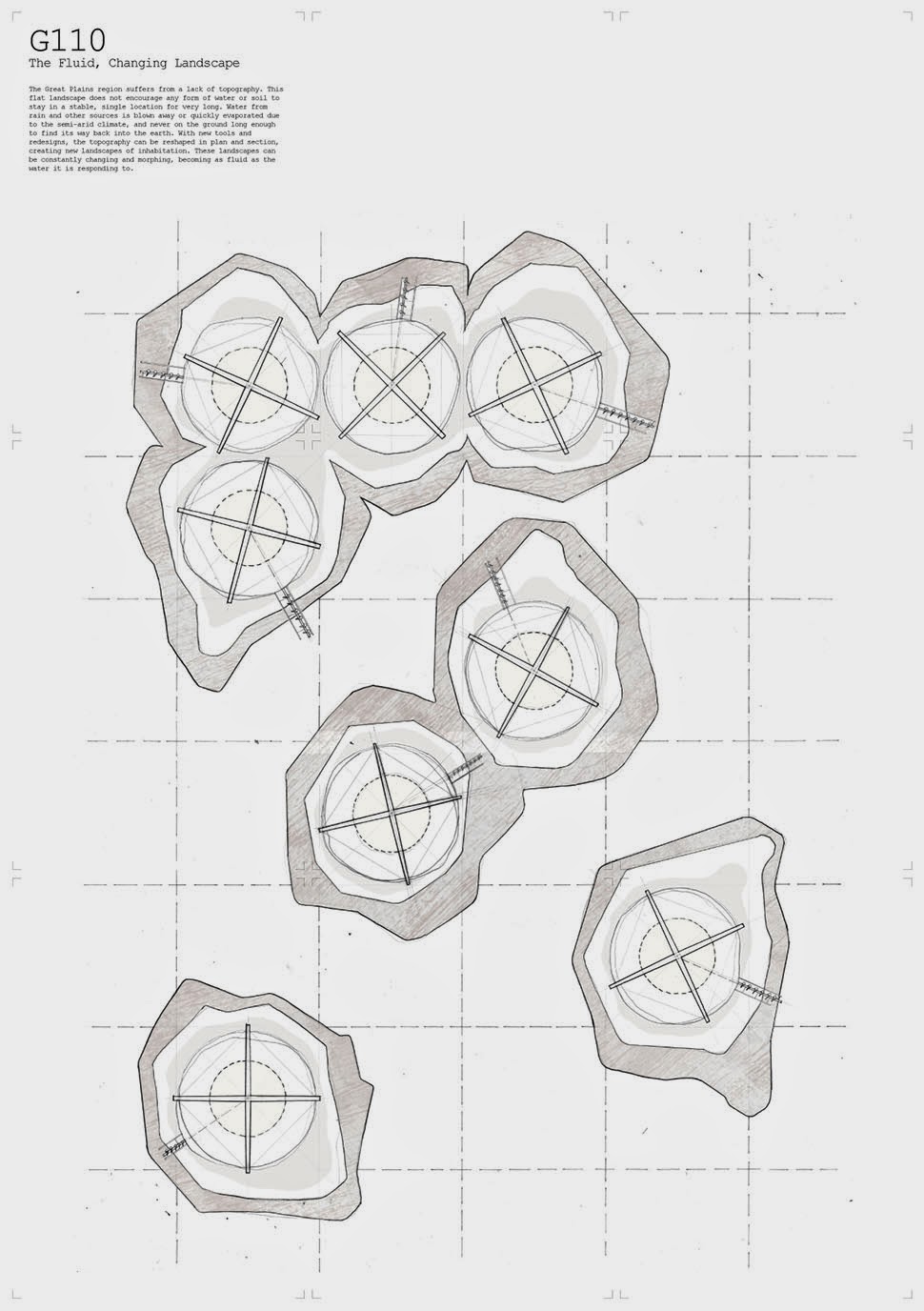

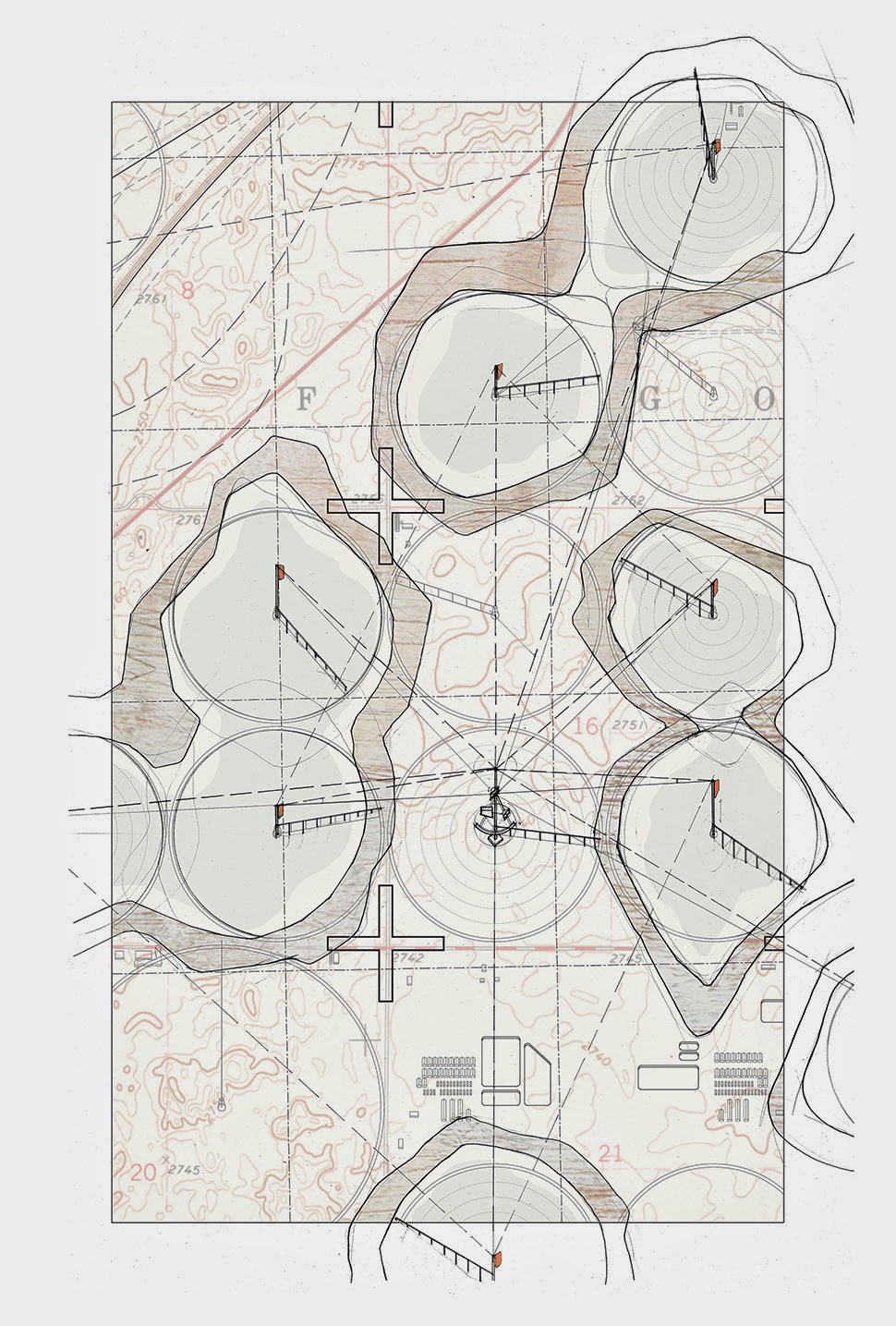

Tool 2: Aquifer Irrigation Ponds

Tool 2 uses the center pivot irrigation rigs to reconstruct the ground, making bowls in the landscape that act as dew ponds. At the same time, the wells become tools and markers to survey the levels of the aquifer below, signifying changes in the depth through elevational changes above. New forms of settlement begin to appear around each ring as a balance is reached between extraction and recharge of the aquifer.

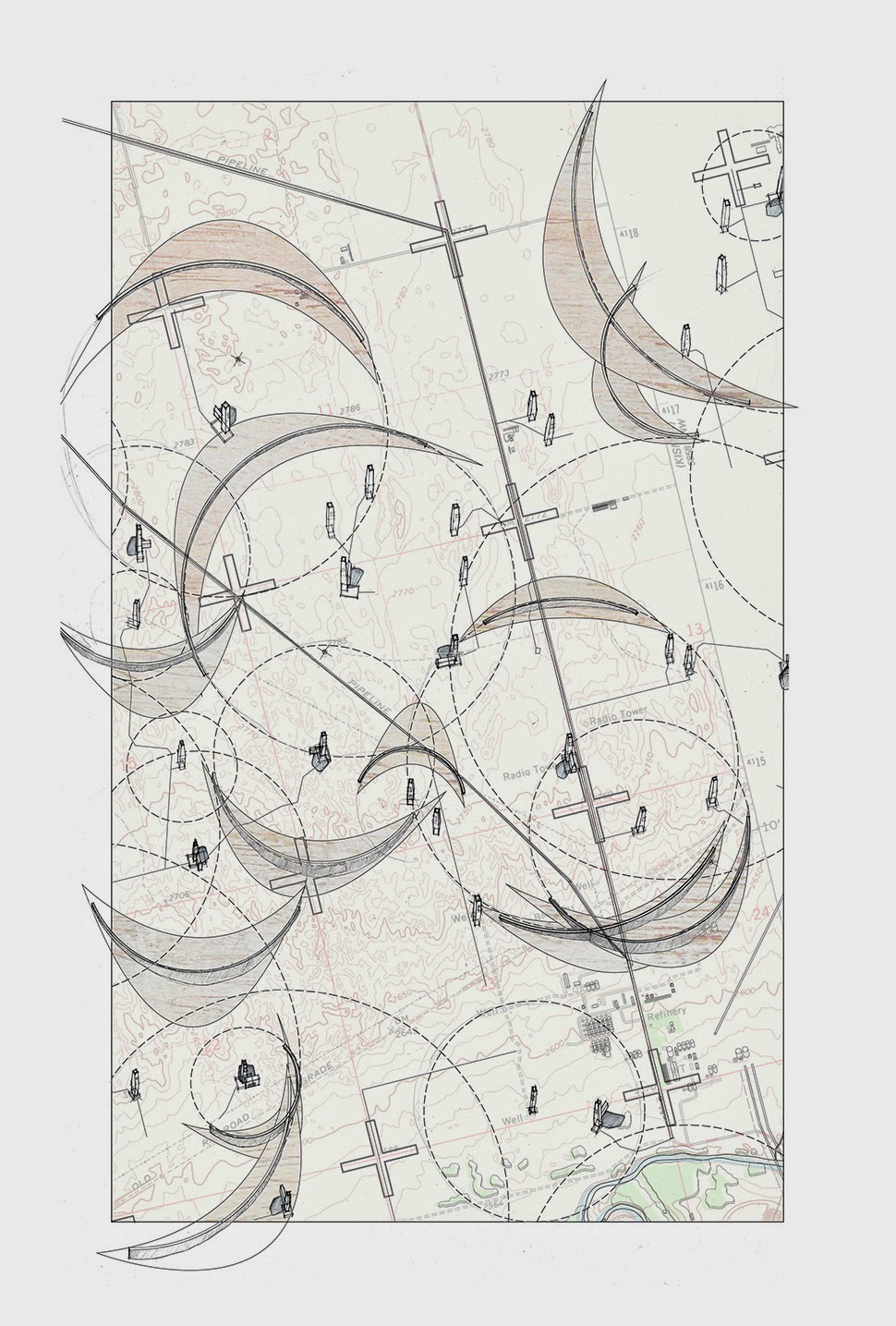

Tool 3: Sand Dunes, Grazing Fields

Tool 3 uses gas wells as new geo-positioning points, redrawing boundaries and introducing controlled grazing and fallowing zones into the region. Walls are also built as markers of the drilling wells below, creating a dune topography to retain more ground water. Each repurposed oil rig becomes an architectural element that both provides protection and feed for grazing animals as well as a core sample viewing station. The abandoned rigs suspend cross sections of the earth to educate visitors of the geological history of the ground they stand on.

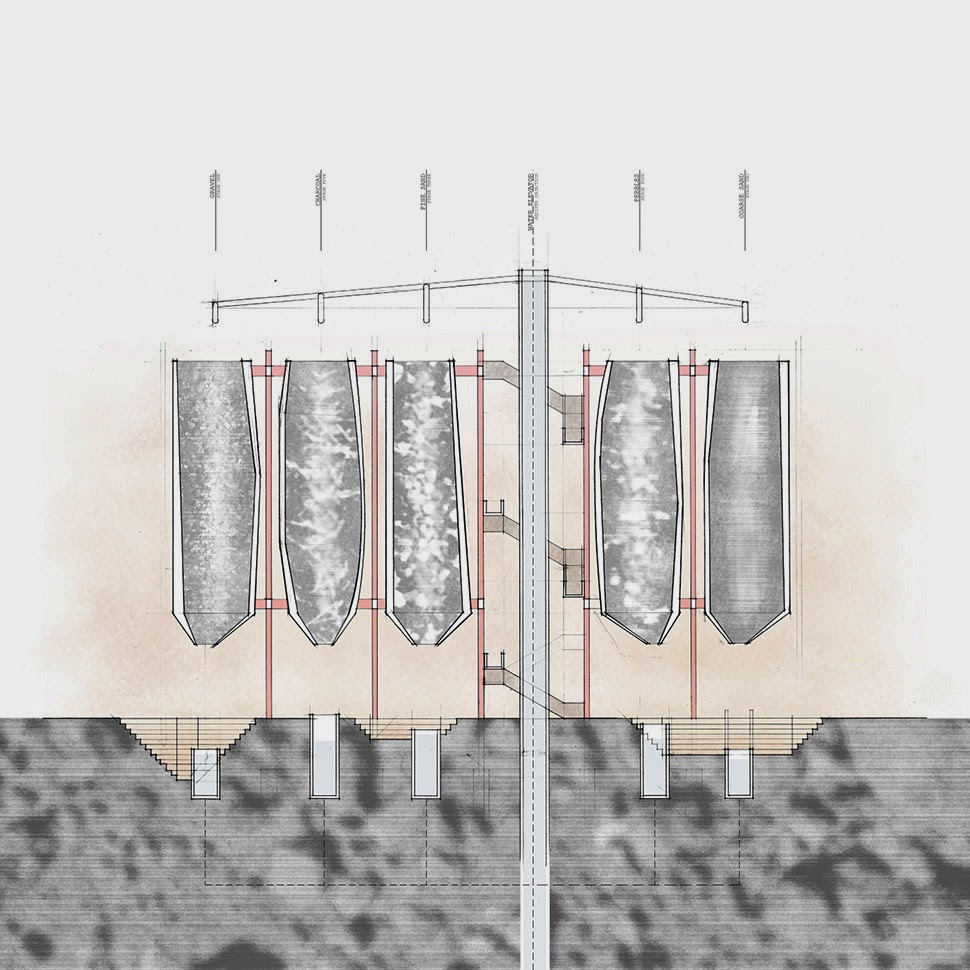

Tool 4: Water Recycling Station

Tool 4 converts the grain elevator into a water recycling station, filling the silos with different densities of sand and stone to filter collected types of water- rain, ground run-off, grey, brackish, etc. Large pavilion like structures are built between houses, collecting water and providing shade underneath. Some housing is converted into family-run markets; the new social space under the pavilions provide for market space. The repurposed grain elevator becomes the storage center for the region’s new water bank. Economic control is brought back to the local scale.

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

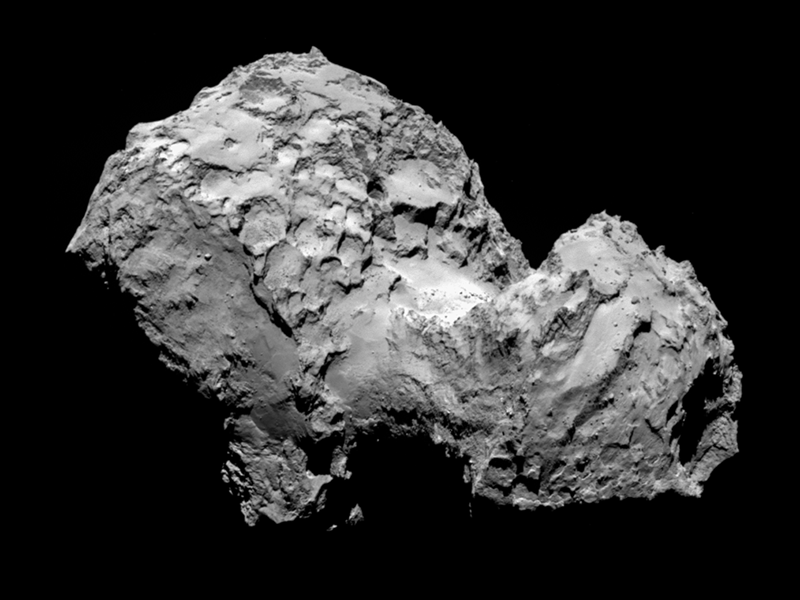

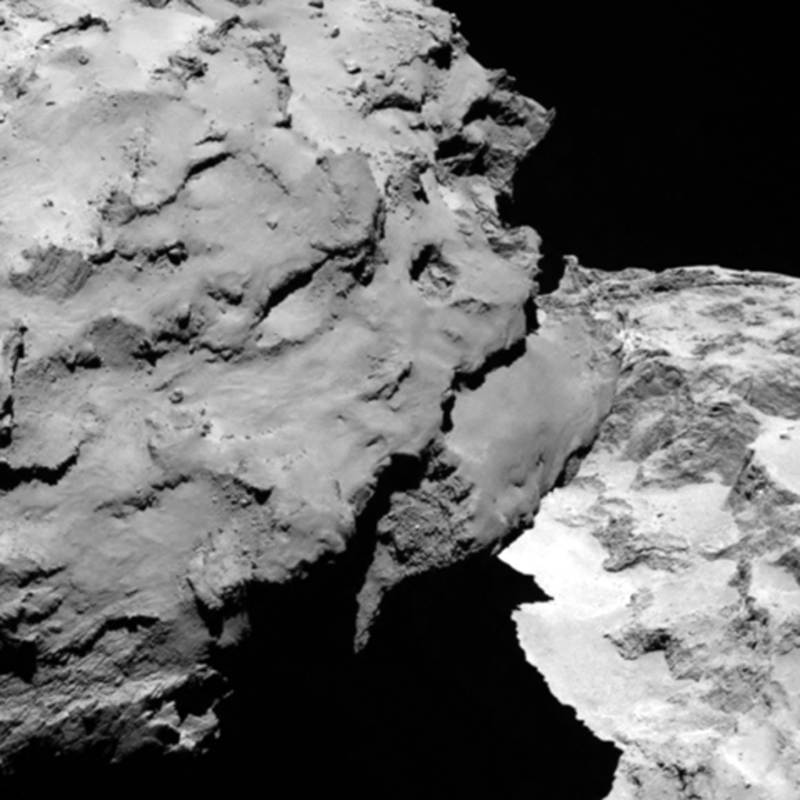

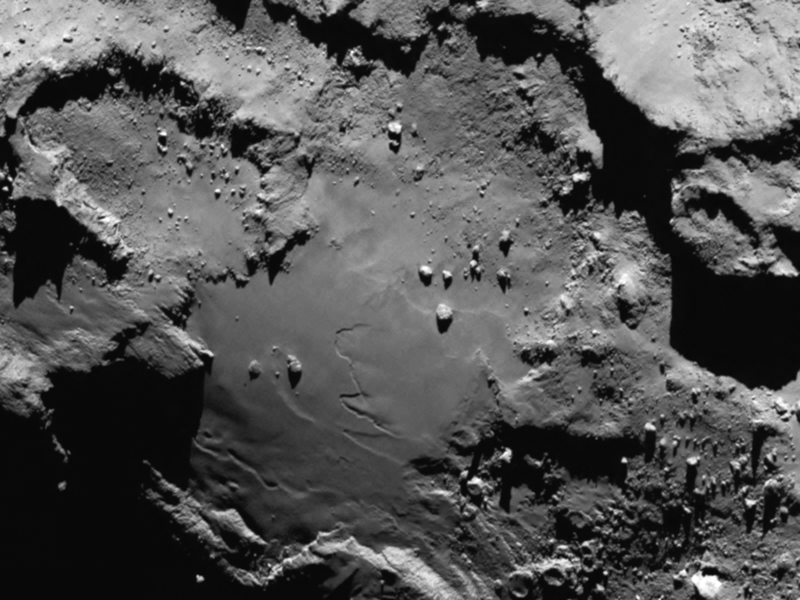

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Wrapped cabin, courtesy

[Image: Wrapped cabin, courtesy

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

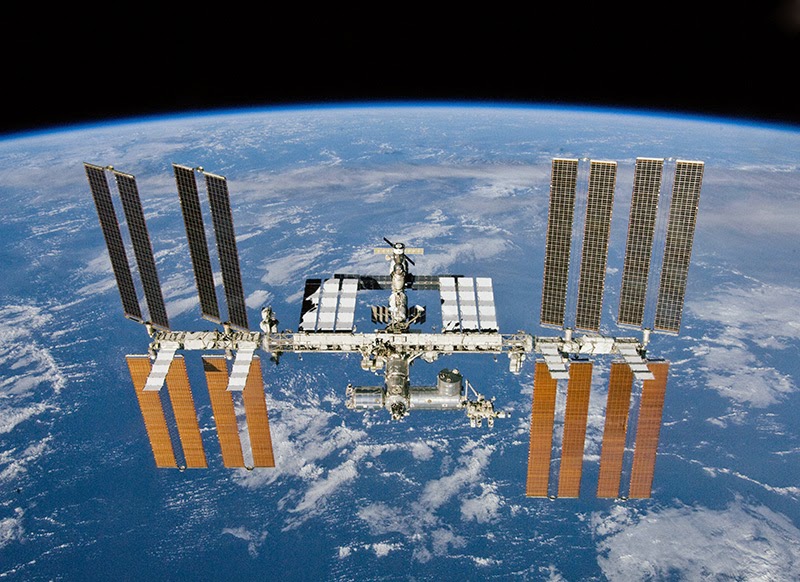

[Image: The International Space Station,

[Image: The International Space Station,  [Image: The South Pacific “spacecraft cemetery”; image remade based on

[Image: The South Pacific “spacecraft cemetery”; image remade based on  [Image: The International Space Station, courtesy NASA].

[Image: The International Space Station, courtesy NASA].

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by

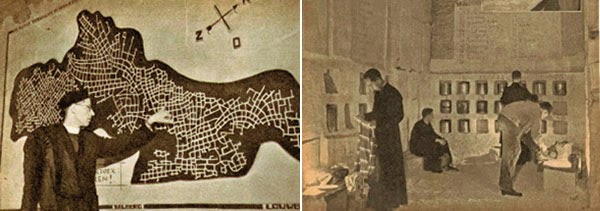

[Image: An entrance to the quarry in Kanne; photo by  [Images: Monks underground; via

[Images: Monks underground; via  The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:

The “streets” were named, but not always easy to follow; however, this didn’t stop officers stationed there from occasionally going out to explore the older tunnels at night. A former employee named Bob Hankinson describes how he used to navigate:  [Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: An entrance into the NATO complex;

[Image: Inside NYC’s

[Image: Inside NYC’s

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of  [Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of  [Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by Heiko Prumers, courtesy of

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

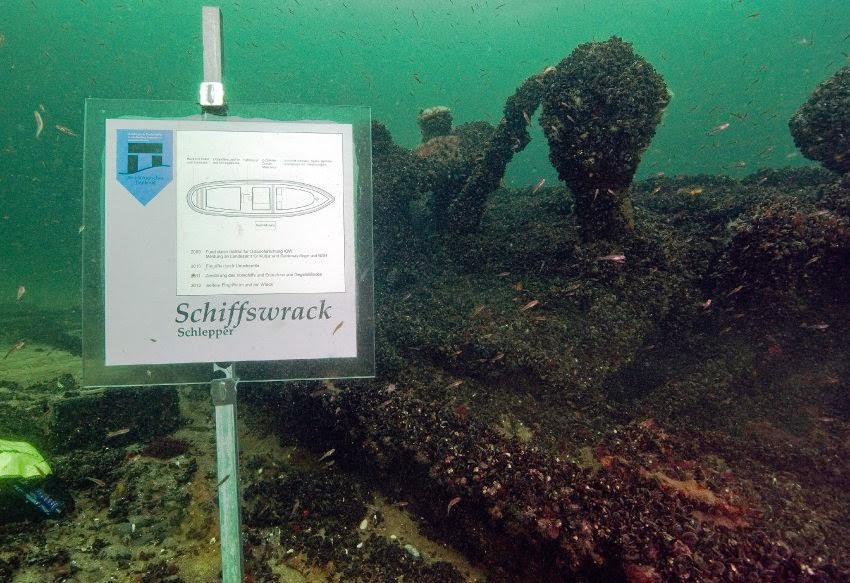

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via  [Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via

[Image: Photo by Martin Siegel/Society of Maritime Archaeology, via