[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

A group of friends, their faces rigorously hidden from public view, find a huge borehole leading down into some tunnels beneath the city.

Not content to just lie there, straining to see more than 260 feet into the deep and merely wondering what might be down there, they do what any enterprising team of explorers would do.

They don mountaineering gear and descend into the pit.

[Images: Photos by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Images: Photos by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

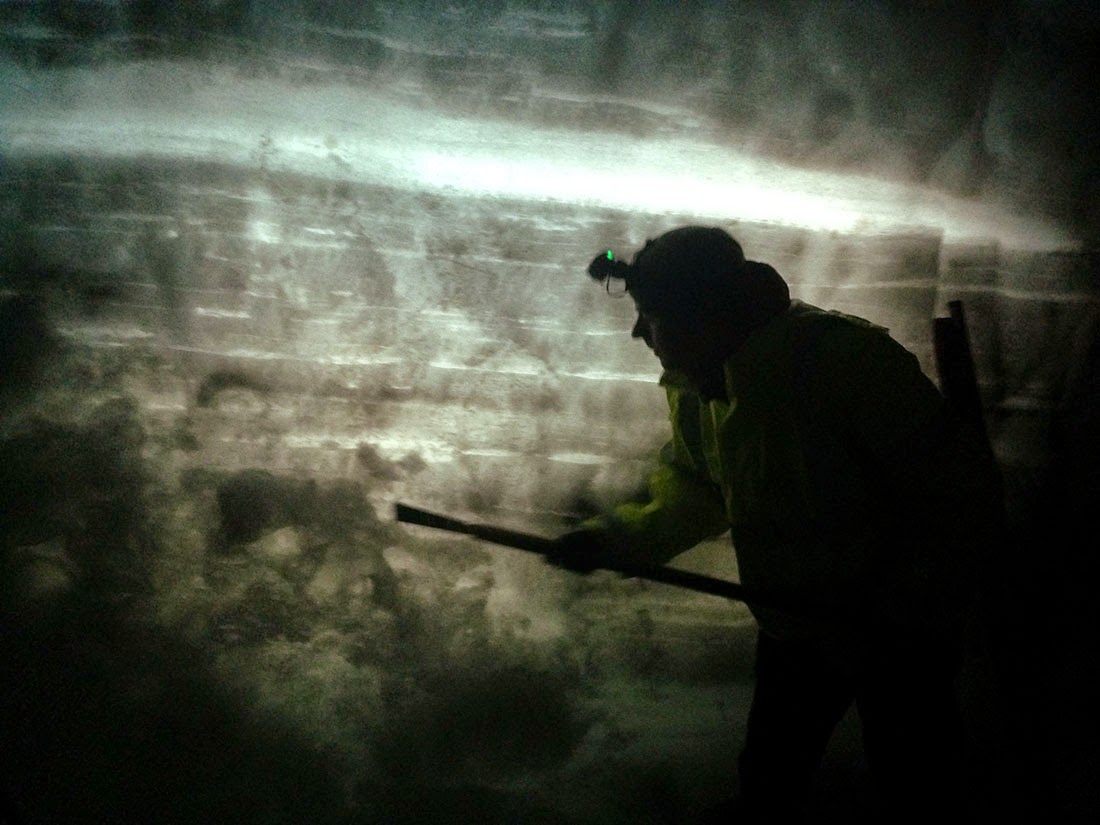

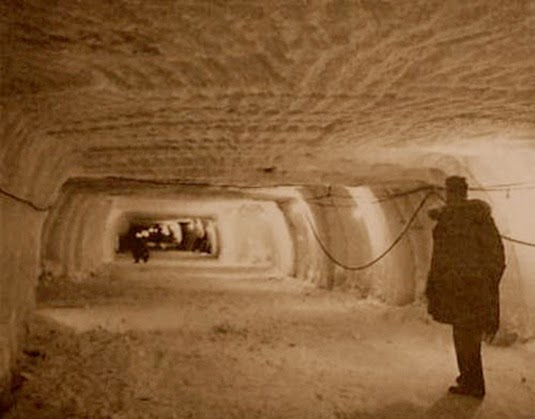

It’s like scaling Mt. Everest in reverse—“descending black ropes,” in their words—swinging ever closer to the entrance to the tunnels, their headlamps and cameras at the ready.

Plus, some weird new myths have been circulating around town: that there’s a monolithic machine down there, something massive and temporarily abandoned beneath the city. It is “the toughest of all the machines. A dormant juggernaut that lies underground.”

They want to find it, to see if the rumors are true—and, who knows, to discover if the machine might still be operational. Imagine what you could do with a discarded tunneling machine seemingly forgotten in the deepest basement of the metropolis. Imagine if you could bring it back to life.

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

Thus begins the next phase of their subterranean quest to find the so-called “Worm Maiden,” this conquering machine-animal lying dormant in its lair somewhere under the streets.

“Hitting our helmets and our backpacks on almost everything we found on the way,” they inched forward on foot.

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

They soon drop their ropes and progress through a series of excavated tunnels and industrial caves, as if puzzling some new route into a pharaoh’s tomb—an Egyptology of urban infrastructure with its own secret chambers and traps.

And, incredibly, they actually do it: they actually find the machine, realizing that the rumors were both true and strangely inaccurate.

That is, the machine is even larger and more extraordinary than they’d been led to believe. It is a sprawling and tentacular presence that blocks the tunnel with the dark bulk of its old valves and pipework, like some ancient engine that wanted to hide itself in a cocoon of its own making.

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

“Walking through the sleeping beauty, through her corridors amongst rust and spiderwebs,” we read, “she looked much bigger than we could have imagined. She didn’t seem to have an end. Eventually we reached a point where we couldn’t go any further, it was full of pipes and unknown mechanisms but the end was intuited.”

The machine was so complex, in other words, that they couldn’t find the other end of it, having to negotiate their way through all its internal doors and control panels.

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

It could be the ultimate joyride—Grand Theft TBM—driving a stolen machine literally through the foundations of the city, carving your own maze through bedrock.

But a way forward was eventually found, and the Kubrickian monolith of this now-stationary drill head was revealed up ahead like some Mayan sculpture in the darkness. Abandoned for now and just lying there: a machine-ruin rusting away in the underground world it had made for itself. The conqueror worm.

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

[Image: Photo by & courtesy of Trackrunners, used with permission].

“It was much better than I had imagined,” we read. The text is like an archaeological report made possible by climbing gear and GoPros. “A twelve meter diameter of pure love just in front of us, was bestial. I couldn’t stop staring at HER. I could see the strain on her, the hard work she had done. The dirt in every part of the face. Pure beauty. All the space around her was filled by a foot of dirty water. A mixture of sand, dirt, water and oil. This mantle of fluids that covered everything was perfect, the vapors fogged my camera lens but the effect was delightfully dramatic. Go and use a filter to look like this. I can see the new Instagram filter now… TBM vapors effect!”

But that’s literally only half the journey. They’ve mountaineered into the planet, like reverse-Alpinists of the inferno—and they go so far as to discover an artificial lake beneath the city, a brackish reservoir that “shone under the light of our torches”—but now they have to get back out, which is not nearly as easy as it had seemed.

There are dozens of other photographs over at Trackrunners, and a much longer version of how everything happened that day; go check it out (and don’t miss their other stories, such as the disused stations beneath Barcelona).

(Thanks to Charles Bronson for the tip.)

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “

[Images: A “

[Images: A “

[Images: A “

[Images: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

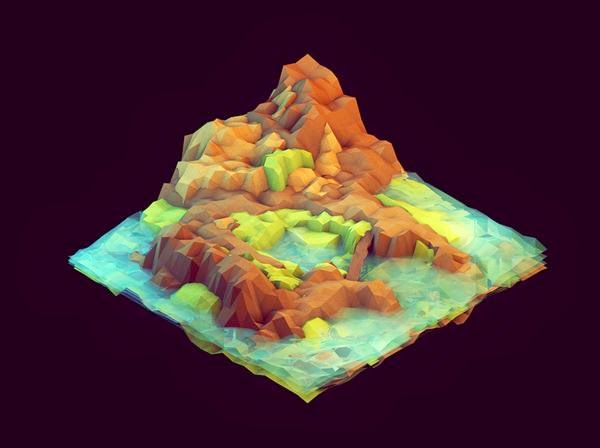

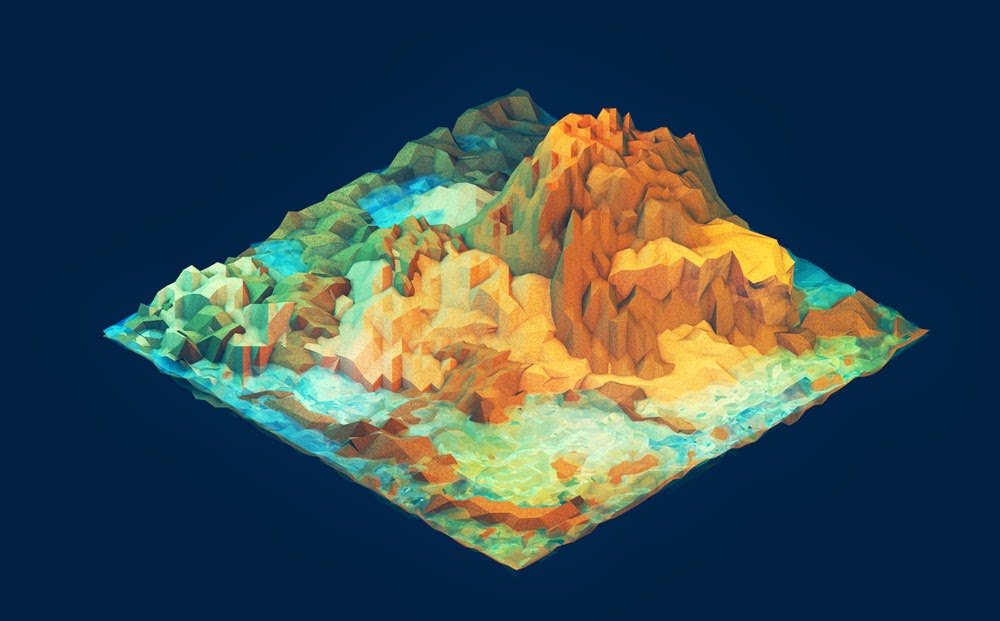

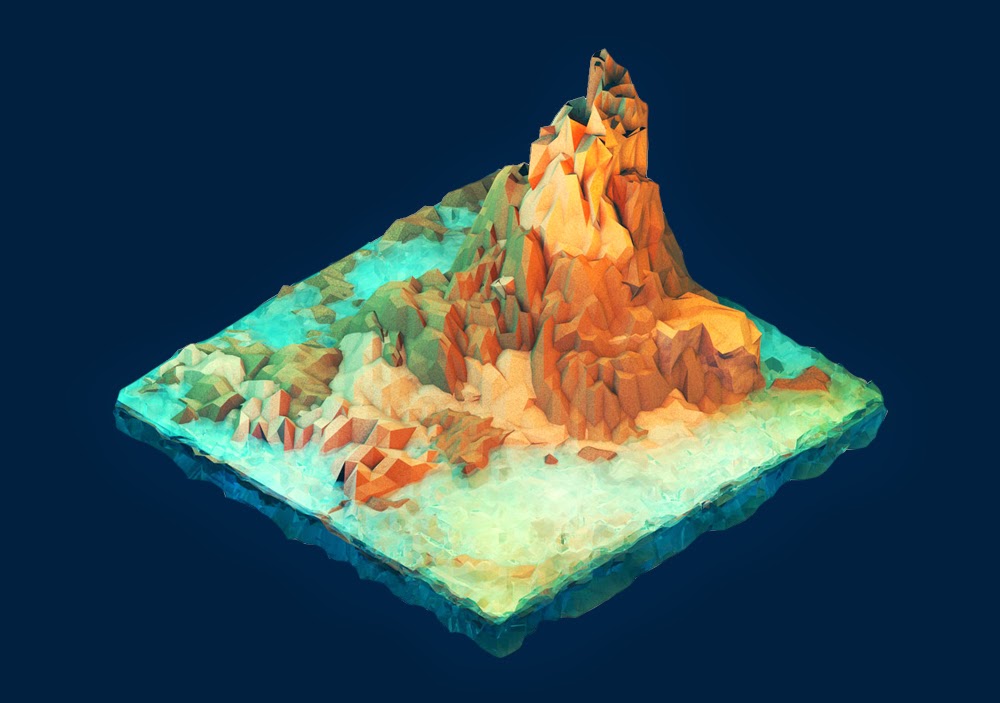

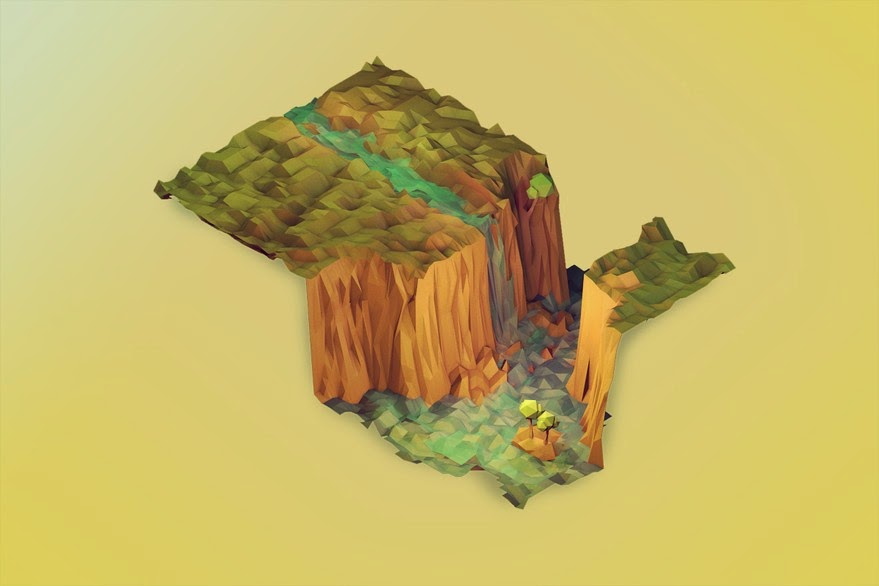

[Image: A “ [Image: A “low-poly” landscape by

[Image: A “low-poly” landscape by

[Images: A “low-poly” landscape by

[Images: A “low-poly” landscape by  [Image: A “low-poly” landscape by

[Image: A “low-poly” landscape by

[Images: A “

[Images: A “

[Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of  [Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of  [Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: A drone from

[Image: A drone from  [Image: A drone from

[Image: A drone from  [Image: A drone from

[Image: A drone from

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Photo: “

[Photo: “ [Photo: “

[Photo: “ [Photo: “

[Photo: “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: Photographer unknown, via

[Image: Photographer unknown, via

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of

[Images: Courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via