Edible Geography explores the exhumation of whole trees in a new post called “Rootstock Archaeology.” Don’t miss the incredible rhizotron, “an underground corridor whose walls consist of forty-eight shuttered windows, which researchers can open to peer out onto the root systems of adjacent trees and plants.”

Category: BLDGBLOG

“A City on Mars is Possible. That’s What All This is About.”

Last week’s successful demonstration of a reusable rocket, launched by Elon Musk’s firm SpaceX, “was a critical step along the way towards being able to establish a city on Mars,” Musk later remarked. The proof-of-concept flight “dramatically improves my confidence that a city on Mars is possible,” he added. “That’s what all this is about.”

Previously, of course, Musk had urged the Royal Aeronautical Society to view Mars as a place where “you can start a self-sustaining civilization and grow it into something really big.” He later elaborated on these ideas in an interview with Aeon’s Ross Anderson, discussing optimistic but still purely speculative plans for “a citylike colony that he expects to be up and running by 2040.” In Musk’s own words, “If we have linear improvement in technology, as opposed to logarithmic, then we should have a significant base on Mars, perhaps with thousands or tens of thousands of people,” within this century.

(Image courtesy of SpaceX. Elsewhere: Off-world colonies of the Canadian Arctic and BLDGBLOG’s earlier interview with novelist Kim Stanley Robinson).

Bonus Levels

Over at AVANT, Lawrence Lek explores the spatial metaphor of “bonus levels,” or what he calls “the continuation of architecture through other means: an ongoing series of fictitious, utopian landscapes conceived as site-specific simulations.”

Pivot

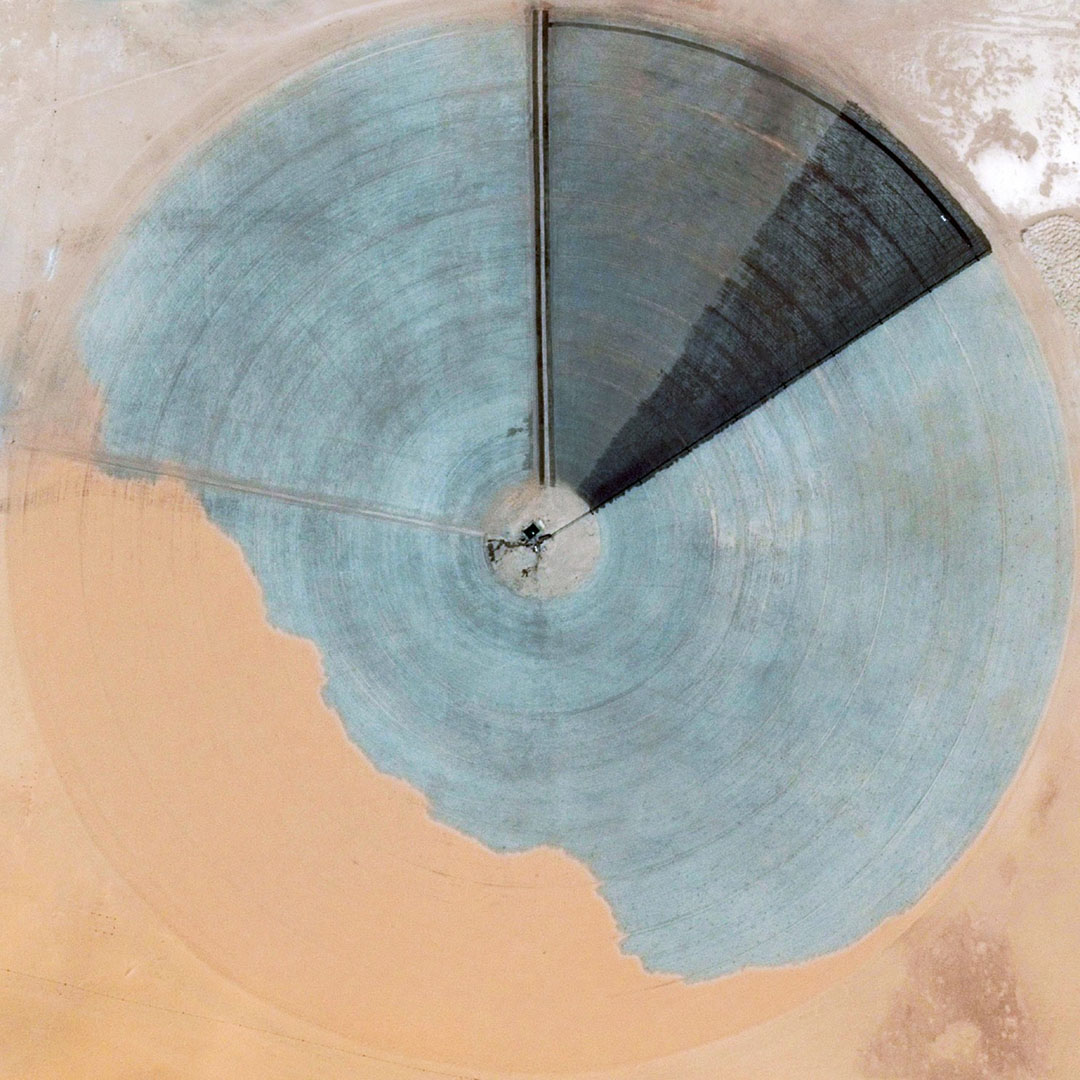

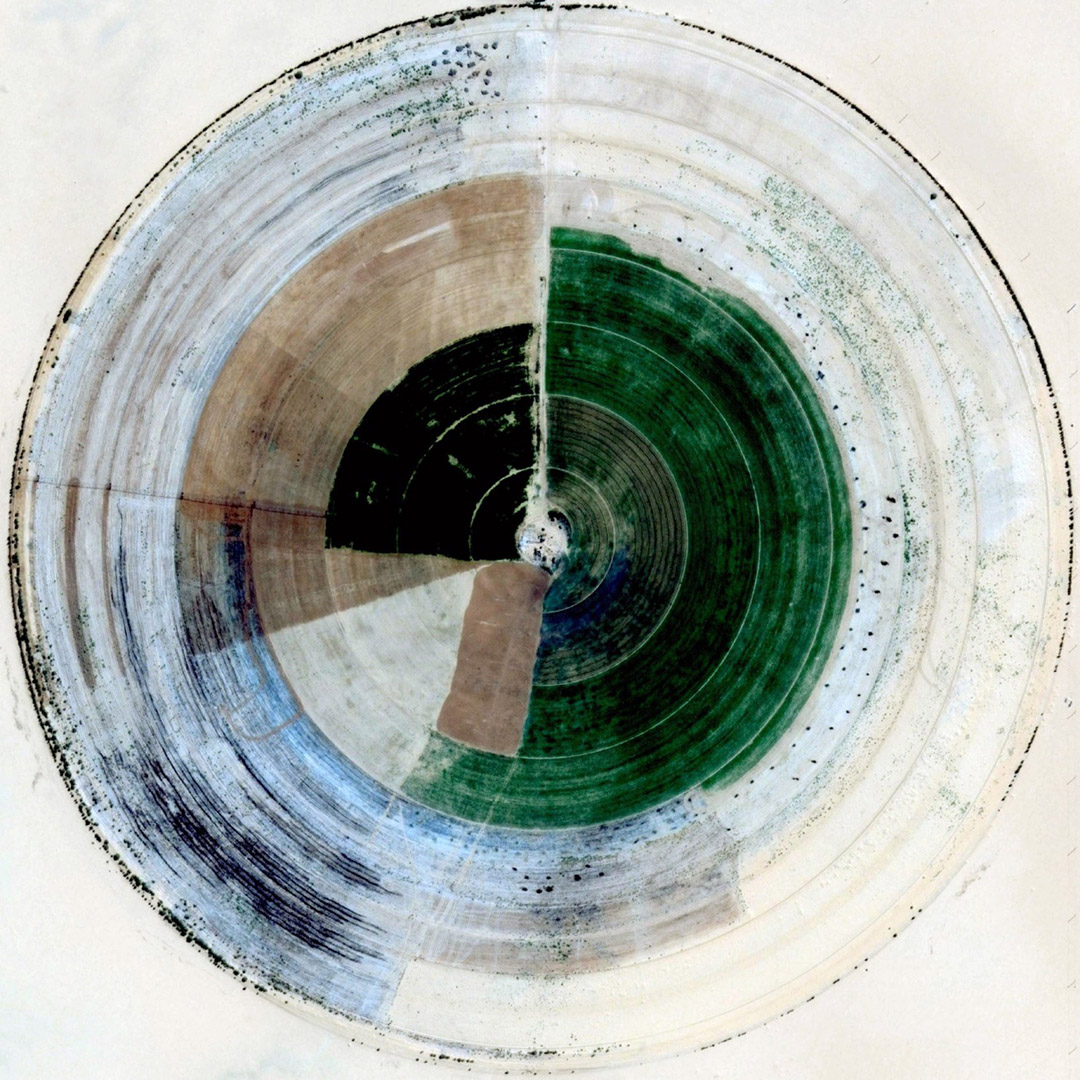

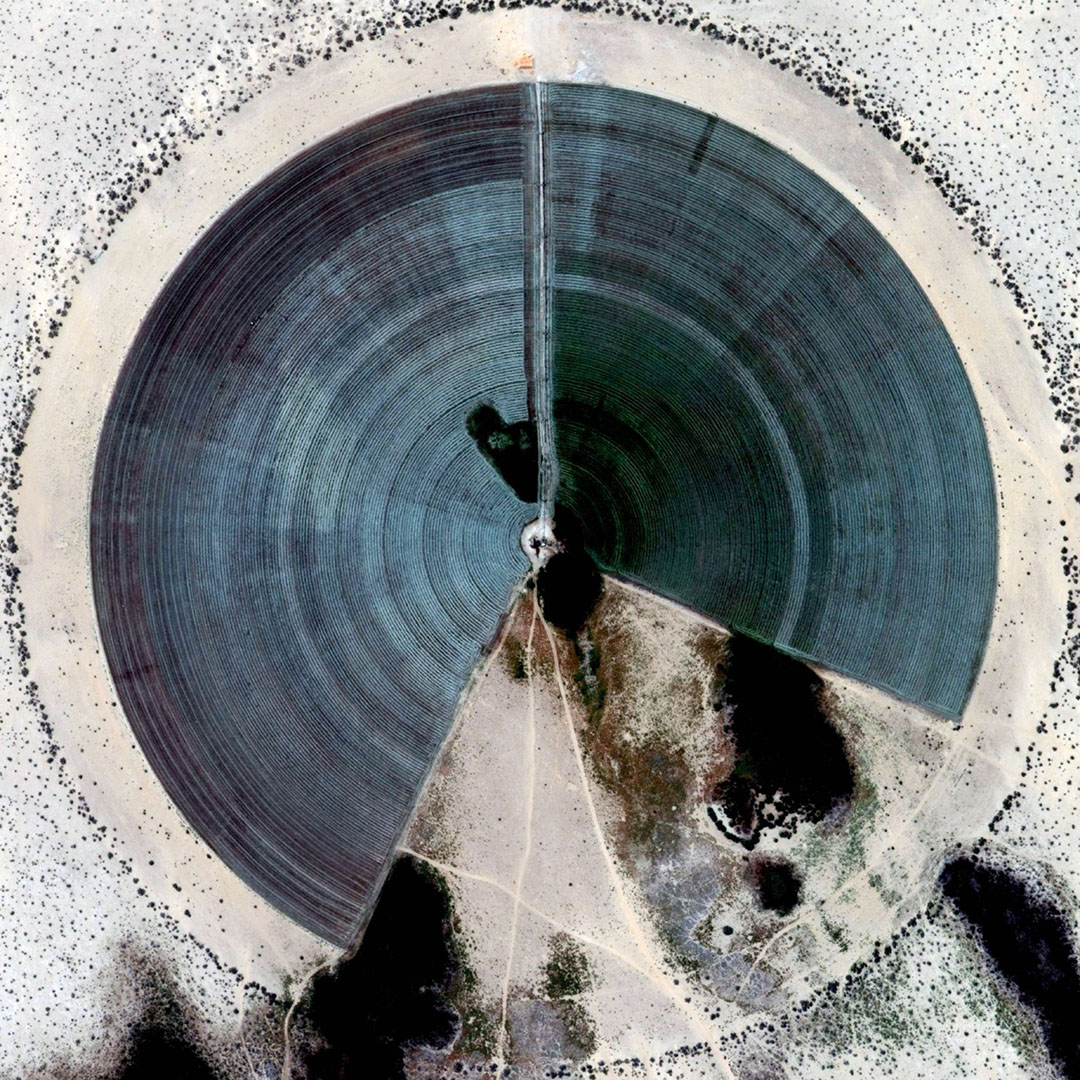

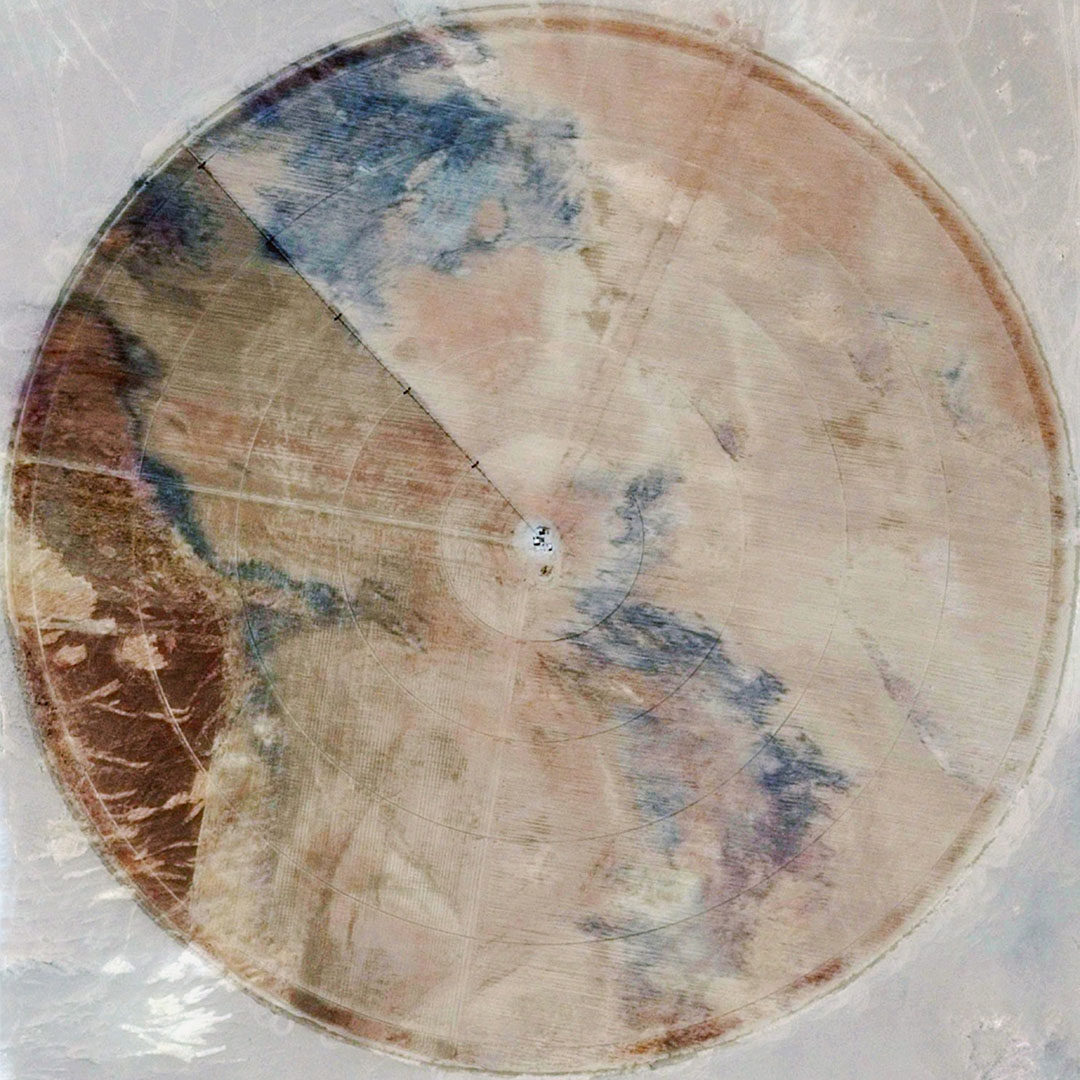

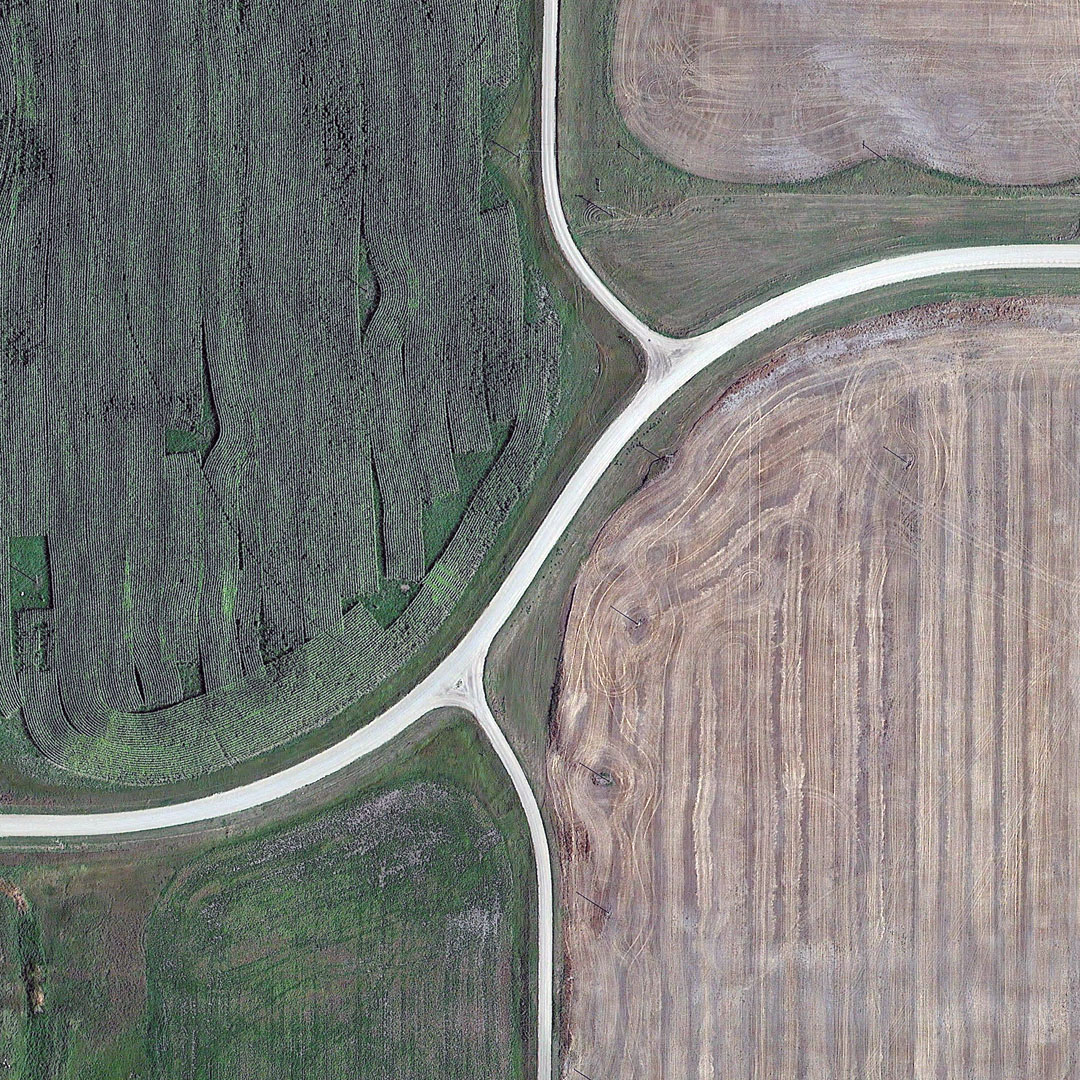

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

The images of “Grid Corrections” seen in the previous post reminded me of an earlier project, also by photographer Gerco de Ruijter, called “Cropped,” previously seen here back in 2012.

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

The images seen here are all satellite views of pivot irrigation systems, taken from Google Earth and cleaned up by de Ruijter for display and printing.

[Images: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Images: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

The resulting textures look like terrestrial LPs disintegrating into the landscape, or vast alien engravings slowly being consumed by sand—

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

—and they are, at times, frankly so beautiful it’s almost hard to believe these landscapes were not deliberately created for their aesthetic effects.

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

Granted, de Ruijter has color-corrected these satellite shots and pushed the saturation, but as metaphorical gardens of pure color and hue, the original pivotscapes are themselves already quite extraordinary.

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Image: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

For a few more examples of these—posted at a much-larger, eye-popping size—click through to the Washington Post or consider watching the original film, called “Crops,” here on BLDGBLOG.

[Images: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Images: From “Cropped” by Gerco de Ruijter; view larger].

[Previously: Grid Corrections].

Grid Corrections

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

In case this is of interest, I’ve got a new article up over at Travel + Leisure about photographer Gerco de Ruijter. De Ruijter recently undertook an exploration of sites in the North American landscape where the Jeffersonian road grid is forced to go askew in order to account for the curvature of the Earth.

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

De Ruijter is already widely known for his work documenting grids and other signs of human-induced geometry in the landscape, from Dutch tree farms to pivot irrigation systems, which gives this new focus an interestingly ironic air.

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

In other words, these are places where a vision of geometric perfection—a seemingly infinite grid, dividing equal plots of land for everyone, extending sea to shining sea—collides with the reality of a spherical planet and must undergo internal deviations.

Those are the “grid corrections” of de Ruijter’s title, and they take the form of otherwise inexplicable T-intersections and zigzag turns in the middle of nowhere.

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

The project includes a series of spherical panoramas de Ruijter made using kite photography at specific corrective intersections outside Wichita, in effect distorting the distortions, a kind of topographical reverb.

[Images: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Images: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

And there is also a further sub-series of satellite images—all taken from Google Earth—stitched together to show intersections where grid corrections occur.

[Image: “Canada/USA 2015 Grid Correction Leota Minnesota,” from “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: “Canada/USA 2015 Grid Correction Leota Minnesota,” from “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

The actual article explains in more detail what these grid corrections are, why they exist in the first place, and how often they appear, including references to James Corner’s Taking Measures Across the American Landscape and to a 2007 post on Alexander Trevi’s blog, Pruned.

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

[Image: From “Grid Corrections” by Gerco de Ruijter, courtesy of the Ulrich Museum of Art].

For more, then, not only check out the Travel + Leisure piece, but click around on de Ruijter’s own website—and, if you’re in The Netherlands, stop by the Van Kranendonk Gallery in The Hague tomorrow, Saturday, December 12th, to see a few examples from “Grid Corrections” on display.

Yodaville

[Image: Yodaville, via Google Maps].

[Image: Yodaville, via Google Maps].

All the Google Maps sleuthing of the Los Angeles “ghost streets” post reminded me of stumbling on a place called Yodaville—seen above—as previously explored here back in 2012. Yodaville is a simulated city in the Arizona desert, deep inside the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, used for targeting exercises.

It is truly in the middle of the nowhere, roughly midway between the Gila Mountains and the U.S./Mexico border.

Its official name is Urban Target Complex (R-2301-West).

(Related: In the Box: A Tour Through the Simulated Battlefields of the U.S. National Training Center).

Whale Song Bunker

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the BBC].

[Image: The old submarine listening station, Isle of Lewis, via the BBC].

This is the most awesomely surreal architectural proposal of 2015: an extremely remote Cold War-era submarine surveillance station on the Isle of Lewis in the Scottish Outer Hebrides might soon be transformed into a kind of benthic concert hall for listening to whale song.

“A community buy-out could see a former Cold War surveillance station turned into a place where tourists can listen to the sound of whales singing,” the BBC reports.

During the Cold War, we read, “the site was part of NATO’s early warning system against Soviet submarines and aircraft, but the Ministry of Defence has no further use for the derelict buildings on the clifftop site.”

“It is now hoped a hydrophone could be placed in the sea to pick up the sound of whales.”

The idea of “derelict buildings on [a] clifftop site” resonating with the artificially amplified sounds of distant whales is amazing, like some fantasy acoustic variation on the “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm.

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm].

[Image: “Dolphin Embassy” by Ant Farm].

I couldn’t find any further word on whether or not this plan is actually moving forward, but, if not, we should totally Kickstart this thing—and, if not there, then perhaps reusing the old abandoned bunkers of the Marin Headlands.

Your own private whale song bunker, reverberating with the inhuman chorus of the deep sea.

(Story originally spotted via Subterranea, the journal of Subterranea Britannica).

A Cordon of Hives

[Images: From The Elephants & Bees Project “Beehive Fence Construction Manual” (PDF)].

[Images: From The Elephants & Bees Project “Beehive Fence Construction Manual” (PDF)].

Designing for humans, insects, and elephants at the same time, University of Oxford zoologist Lucy King has developed “the honey fence system,” Edible Geography explains.

[Images: Via The Elephants & Bees Project].

[Images: Via The Elephants & Bees Project].

A honey fence is “a series of hives, suspended at ten-metre intervals from a single wire threaded around wooden fence posts. If an elephant touches either a hive or the wire, all the bees along the fence line feel the disturbance and swarm out of their hives in an angry, buzzing cloud.”

“By encircling a village with a cordon of hives,” we read, “the village’s crops are protected.”

Read more at Edible Geography.

Comparative Astral Isochrones

[Image: Isochronic map of travel distances from London, from An Atlas of Economic Geography (1914) by John G. Bartholomew (via)].

[Image: Isochronic map of travel distances from London, from An Atlas of Economic Geography (1914) by John G. Bartholomew (via)].

“This is an isochronic map—isochrones being lines joining points accessible in the same amount of time—and it tells a story about how travel was changing,” Simon Willis explains over at Intelligent Life. The map shows you how long it would take to get somewhere, embarking from London:

You can get anywhere in the dark-pink section in the middle within five days–to the Azores in the west and the Russian city of Perm in the east. No surprises there: you’re just not going very far. Beyond that, things get a little more interesting. Within five to ten days, you can get as far as Winnipeg or the Blue Pearl of Siberia, Lake Baikal. It takes as much as 20 days to get to Tashkent, which is closer than either, or Honolulu, which is much farther away. In some places, a colour sweeps across a landmass, as pink sweeps across the eastern United States or orange across India. In others, you reach a barrier of blue not far inland, as in Africa and South America. What explains the difference? Railways.

Earlier this year, when a private spacecraft made it from the surface of the Earth to the International Space Station in less than six hours, the New York Times pointed out that “it is now quicker to go from Earth to the space station than it is to fly from New York to London.”

[Image: From Twitter].

[Image: From Twitter].

In the context of Bartholomew’s map, it would be interesting to re-explore isochronal cartography in our own time, to visualize the strange spacetime we live within today, where the moon is closer than parts of Antarctica and the International Space Station is a shorter trip than flying to Heathrow.

(Map originally spotted via Francesco Sebregondi).

Howl

I watched this video with the typical ennui of your average internet user—expecting to hear nothing at all, really, before going back to other forms of online procrastination—but holy Hannah. This is a pretty loud building.

Although I would be making surreptitious ambient field recordings—and rhapsodizing to my sleepless friends about the unrealized acoustic dimensions of contemporary architecture—I have to say I’d be pretty unenthused to have this thing howling all day, everyday, in my neighborhood.

It’s Manchester’s Beetham Tower. It cost £150 million to build, and its accidental sounds are apparently now “the stuff of legend.”

(Spotted via Justin Davidson. This actually reminds me of when my housemate in college taught himself to play the saw and I had no idea what was happening).

In the Garden of 3D Printers

[Image: Unrelated image of incredible floral shapes 3D-printed by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg (via)].

[Image: Unrelated image of incredible floral shapes 3D-printed by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg (via)].

A story published earlier this year explained how pollinating insects could be studied by way of 3D-printed flowers.

The actual target of the study was the hawkmoth, and four types of flowers were designed and produced to help understand the geometry of moth/flower interactions, including how “the hawkmoth responded to each of the flower shapes” and “how the flower shape affected the ability of the moth to use its proboscis (the long tube it uses as a mouth).”

Of course, a very similar experiment could have been done using handmade model flowers—not 3D printers—and thus could also have been performed with little fanfare generations ago.

But the idea that a surrogate landscape can now be so accurately designed and manufactured by printheads that it can be put into service specifically for the purpose of cross-species dissimulation—that it, tricking species other than humans into thinking that these flowers are part of a natural ecosystem—is extraordinary.

[Image: An also unrelated project called “Blossom,” by Richard Clarkson].

[Image: An also unrelated project called “Blossom,” by Richard Clarkson].

Many, many years ago, I was sitting in a park in Providence, Rhode Island, one afternoon reading a copy of Germinal Life by Keith Ansell Pearson. The book had a large printed flower on its front cover, wrapping over onto the book’s spine.

Incredibly, at one point in the afternoon a small bee seemed to become confused by the image, as the bee kept returning over and over again to land on the spine and crawl around there—which, of course, might have had absolutely nothing to do with the image of a printed flower, but, considering the subject matter of Ansell Pearson’s book, this was not without significant irony.

It was as if the book itself had become a participant in, or even the mediator of, a temporary human/bee ecosystem, an indirect assemblage created by this image, this surrogate flower.

In any case, the image of little gardens or entire, wild landscapes of 3D-printed flowers so detailed they appear to be organic brought me to look a little further into the work of Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg, a few pieces of whose you can see in the opening image at the top of this post.

Their 3D-printed floral and coral forms are astonishing.

[Image: “hyphae 3D 1” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

[Image: “hyphae 3D 1” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

Rosenkrantz’s Flickr page gives as clear an indication as anything of what their formal interests and influences are: photos of coral, lichen, moss, mushrooms, and wildflowers pop up around shots of 3D-printed models.

They sometimes blend in so well, they appear to be living specimens.

[Image: Spot the model; from Jessica Rosenkrantz’s Flickr page].

[Image: Spot the model; from Jessica Rosenkrantz’s Flickr page].

There is an attention to accuracy and detail in each piece that is obvious at first glance, but that is also made even more clear when you see the sorts of growth-studies they perform to understand how these sorts of systems branch and expand through space.

[Image: “Floraform—Splitting Point Growth” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

[Image: “Floraform—Splitting Point Growth” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

The organism as space-filling device.

And the detail itself is jaw-dropping. The following shot shows how crazy-ornate these things can get.

[Image: “Hyphae spiral” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

[Image: “Hyphae spiral” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

Anyway, while this work is not, of course, related to the hawkmoth study with which this post began, it’s nonetheless pretty easy to get excited about the scientific and aesthetic possibilities opened up by some entirely speculative future collaboration between these sorts of 3D-printed models and laboratory-based ecological research.

One day, you receive a mysterious invitation to visit a small glass atrium constructed atop an old warehouse somewhere on the outskirts of New York City. You arrive, baffled as to what it is you’re meant to see, when you notice, even from a great distance, that the room is alive with small colorful shapes, flickering around what appears to be a field of delicate flowers. As you approach the atrium, someone opens a door for you and you step inside, silent, slightly stunned, noticing that there is life everywhere: there are lichens, orchids, creeping vines, and wildflowers, even cacti and what appears to be a coral reef somehow inexplicably growing on dry land.

But the room does not smell like a garden; the air instead is charged with a light perfume of adhesives.

[Image: “Hyphae crispata #1 (detail)” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

[Image: “Hyphae crispata #1 (detail)” by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg].

Everything you see has been 3D-printed, which comes as a shock as you begin to see tiny insects flittering from flowerhead to flowerhead, buzzing through laceworks of creeping vines and moss—until you look even more carefully and realize that they, too, have been 3D-printed, that everything in this beautiful, technicolor room is artificial, and that the person standing quietly at the other end amidst a tangle of replicant vegetation is not a gardener at all but a geometrician, watching for your reaction to this most recent work.