Formless and ancient things from the depths of our planet move beneath Los Angeles, unexpectedly setting fire to sidewalks and burning whole businesses to the ground. Welcome to urban life atop a still-active oil field.

Sliding around beneath the surface of Los Angeles is something dark, primordial, and without clear form. It seeps up into the city from below through even the smallest cracks and drains. Infernal, it can cause fires and explosions; toxic, it can debilitate, poison, and kill.

Near downtown Los Angeles, at 14th Place and Hill Street, a small extraction firm called the St. James Oil Corporation runs an active oil well. In 2006, the firm presided over a routine steam-injection procedure known as “well stimulation.” The purpose was simple: a careful and sustained application of steam would heat up, liquefy, and thus make available for easier harvesting some of the thick petroleum deposits, or heavy oil, beneath the neighborhood.

But things didn’t quite go as planned. As explained by the Center for Land Use Interpretation—a local non-profit group dedicated to documenting and analyzing land usage throughout the United States—“the subterranean pressure forced oily ooze and smells out of the ground,” causing a nauseating “goo” to bubble over “into storm drains, streets, and basements” as far as two blocks away.

The sudden appearance of this black tide beneath the neighborhood even destabilized the nearby road surface, leading to its emergency closure, and 130 people had to be evacuated. It took weeks to pump these toxic petroleum byproducts out of the basements and to resurface the street; the firm itself was later sued by the city.

While this was an industrial accident, hydrocarbons are, in fact, almost constantly breaking through the surface of Los Angeles, both in liquid and gaseous form. These are commonly known as seeps, and the most famous example is also an international tourist attraction: the La Brea Tar Pits, with its family-friendly museum on Wilshire Boulevard.

The “tar” here is actually liquid asphalt or pitch, and it is one of many reasons why humans settled the region in the first place. Useful both for waterproofing and for its flammability, this sticky substance has been exploited by humans in the region for literally thousands of years—and it has also given L.A. some of its most impressive paleontological finds.

[Image: Tar pushes up through cracks in the sidewalk on Wilshire Boulevard, near the La Brea Tar Pits; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Tar pushes up through cracks in the sidewalk on Wilshire Boulevard, near the La Brea Tar Pits; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

In other words, precisely because they are so dangerous, the tar pits are a veritable archive of extinct species; these include mastodons, saber-toothed tigers, and dire wolves, examples of which have been found fatally mired in the black mess seeping up from the deep. Groups of these now long-dead creatures once wandered across an otherworldly landscape of earthquakes and extinct volcanoes, an active terrain pockmarked with eerie bubbling cauldrons of flammable liquid asphalt.

What’s so interesting about contemporary life in Southern California is that this surreal, prehistoric landscape never really went anywhere: it’s simply been relegated to the background, invisibly buried beneath strip malls, car dealerships, and sushi restaurants. Every natural tar seep and artificial oil well here can be seen as an encounter with this older, stranger world trying to break back through into our present experience.

What humans choose to do with this primordial stuff leaking through the cracks can often be almost comical. Architect Ben Loescher, who has given tours of the region’s oil infrastructure for the Center for Land Use Interpretation, points out that many buildings near Lafayette Park must contend with a constant upwelling of asphalt. He sent me a photograph showing a line of orange utility buckets arranged as an ingenious but absurd stopgap measure against the endless and unstoppable goo.

[Image: A makeshift system for capturing the near-constant tar and liquid asphalt leaking up from below a building near Lafayette Park; photo by Ben Loescher].

[Image: A makeshift system for capturing the near-constant tar and liquid asphalt leaking up from below a building near Lafayette Park; photo by Ben Loescher].

Nearby, Loescher added, parking lots are a great place to see the onslaught. Many are constantly but slowly flooding with tar and asphalt, to the point that one lot—run by a karaoke club—is struck so badly that the tar is actually visible on Google Maps. “That parking lot is riddled with seeps, as well. When it gets hot, the parking lot sort of re-asphalts itself,” Loescher explains, “and they have to put down tarps on top of it so the cars don’t get stuck.” A much larger gravel lot across the street also exhibits multiple sites of seepage, as if pixelating from below with black matter.

Loescher emphasized that these sites are by no means limited to the La Brea Tar Pits. They can be found throughout the Los Angeles basin, beneath sidewalks, yard, parking lots, and even in people’s basements. To exaggerate for dramatic effect, it’s as if the premise of The Blob was at least partially inspired by a true story—one that has been taking place for hundreds of thousands of years throughout Southern California, and that involves, instead of a visitor from space, something ancient and pre-human forcing its way up from below.

[Image: Liquid asphalt leaking upward into the parking lot of a Los Angeles karaoke club; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Liquid asphalt leaking upward into the parking lot of a Los Angeles karaoke club; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

In a short book called Making Time: Essays on the Nature of Los Angeles, writer William L. Fox explores the remnant gas leaks and oil seeps of the city. At times, it reads as if he is describing the backdrop of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. Such is the strange and permanent apocalypse of 21st-century L.A.

Fox writes, for example, that “a methane vent opened up in the middle of Fairfax Street” back in 1985, and that it “burned uncontrollably for days before it could be put out.” At night, it was a world lit by flames. Astonishingly, he adds, in 1962 “a Hawthorne woman had a fire under her house—a house with no basement. She located the source of the problem when she went outside and touched a match to a crack in the sidewalk: A flame ran down to it.”

This city where sidewalks burn and sewers fill with oily ooze is a city built here almost specifically for that very reason; Los Angeles, in many ways, is a settlement founded on petroleum byproducts, and the oil industry for which the city was once known never actually left. It just got better at hiding itself.

It is already well known that there are oilrigs disguised in plain sight all over the city. The odd-looking tower behind Beverly Hills High School, for example, is actually a camouflaged oilrig; an active oil field runs beneath the classrooms and athletic fields. Even stranger, the enormous synagogue at Pico and Doheny is not a synagogue at all, but a movable drilling tower designed to look like a house of worship, as if bizarre ceremonies for conjuring a literal black mass out of the bowels of the Earth take place here, hidden from view. If you zoom in on Google Maps, you can just make out the jumbles of industrial machinery tucked away inside.

However, amidst all of this still-functional oil infrastructure, there are ruins: abandoned wells, capped drill sites, and derelict pumping stations that have effectively been erased from public awareness. These, too, play a role in the city’s subterranean fires and its poisonous breakouts of black ooze.

As Fox explains in Making Time, a labyrinth of aging pipelines and forgotten wells crisscrosses the city. He explains that the Salt Lake Oil Field—which underlies the La Brea Tar Pits, sprawls below an outdoor shopping center known as The Grove, and continues deep into the surrounding neighborhoods—once contained as many as 1,500 operative oil wells. However, most of these “have long since been abandoned and are virtually invisible,” he writes, and, alarmingly, “roughly 300 are unaccounted for.”

These “unaccounted for” oil wells are out of sight and out of mind—but it should not be assumed that they are safely or permanently capped. Indeed, the Salt Lake Oil Field actually “appears to be repressurizing with oil and water,” like an underground blister come back to life, Fox writes. This only raises the stakes of “a hazard already complicated by the lack of knowledge about the exact location of all the wells on the property.” Only 10 years ago, for example, “an orphaned well in Huntington Beach blew out in a gusher forty feet high, spraying oil and methane over one-half square mile, a hazardous-waste problem that will become more common.”

[Image: The Baldwin Hills old field; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: The Baldwin Hills old field; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

Due to its centrality, the Salt Lake field plays an outsized role in terms of strange petroleum events in the city. The Salt Lake was behind the multiday methane fire in the middle of Fairfax Avenue, for example, and behind arguably the most well known and certainly most destructive reminder of the city’s subterranean presence.

In 1989, in a busy strip mall at Fairfax and 3rd Street, a Ross Dress for Less began to fill with methane gas leaking up from a large pocket connected to the oil field below. Somehow, it had broken through the natural clay boundary that should have held it in place, and the methane thus easily seeped up into the storage rooms, closets, and retail galleries of the discount clothing giant.

Before long, the methane ignited and the entire store blew up.

[Image: Screen grab from YouTube].

[Image: Screen grab from YouTube].

This was by no means an insubstantial explosion—you should watch the aftermath on YouTube—as the entire façade of the building was blown to pieces, the roof collapsed, and dozens of people were disfigured by the detonation.

The resulting fires burned for hours. Small fires roared out of nearby sewer grates, and red and orange flames flickered out of even the tiniest cracks in the sidewalk, like some weird vision of Hell burning through the discount blouses and cheap drywall of this obliterated shopping center.

[Image: Flames burn through cracks in the sidewalk; screen grab from YouTube].

[Image: Flames burn through cracks in the sidewalk; screen grab from YouTube].

While reporting the tragedy, a local newscaster worryingly informed his viewers that it was simply “too early to tell where or when [the methane] might surface again”—in other words, that there could very well be further explosions. This paranoia—that there is something down there, some inhuman Leviathan stirring beneath the city, and that no one really knows when and where it will strike next—continues to this day.

Even at the time of the explosion, the possibility that city workers might inadvertently drill into a methane pocket beneath the neighborhood became one of the chief reasons for blocking the construction of a new subway line in the area. This same fear has recently resurfaced as the number one excuse for blocking a proposed subway through Beverly Hills.

Back in 2012, local parents released a video urging the city to stop the expansion of subterranean public transit through their neighborhood, concerned that it would cause Beverly Hills High School to explode. (The fact that stopping the subway would also keep certain economic undesirables out of their streets and shopping districts was just a fringe benefit.)

In any case, the narrative resonance of all this is impossible to deny. Formless and ancient things from the depths of our planet move beneath the city, unexpectedly setting fire to sidewalks and burning whole businesses to the ground. Taken out of context, this could be the plot of a new horror film—but it’s just urban life atop a still-active oil field.

As Matthew Coolidge, director of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, explained it to me, the city “is really just a giant scab of petroleum-fueled activities,” an impermanently sealed cap atop this buried monstrosity.

It is worth considering, then, next time you step over a patch of tar on the sidewalk, that the black gloom still bubbling up into people’s yards and basements, still re-asphalting empty gravel parking lots, is actually an encounter with something undeniably old and elementally powerful.

In this sense, Los Angeles is more than just a city; it is a kind of interface between a petrochemical lifestyle of cars and freeways and the dark force that literally fuels it, a subterranean presence that predates us all by millions of years and that continues to wander freely beneath L.A.’s tangled streets and buildings.

(Note: This piece was originally published on The Daily Beast. I have also written about the La Brea Tar Pits and William L. Fox’s book in Landscape Futures. Opening image: a close-up of Hell, from “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymous Bosch, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain).

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: (top) “

[Images: (top) “ [Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, via

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of  [Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of  [Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: Jasper National Park, courtesy of

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

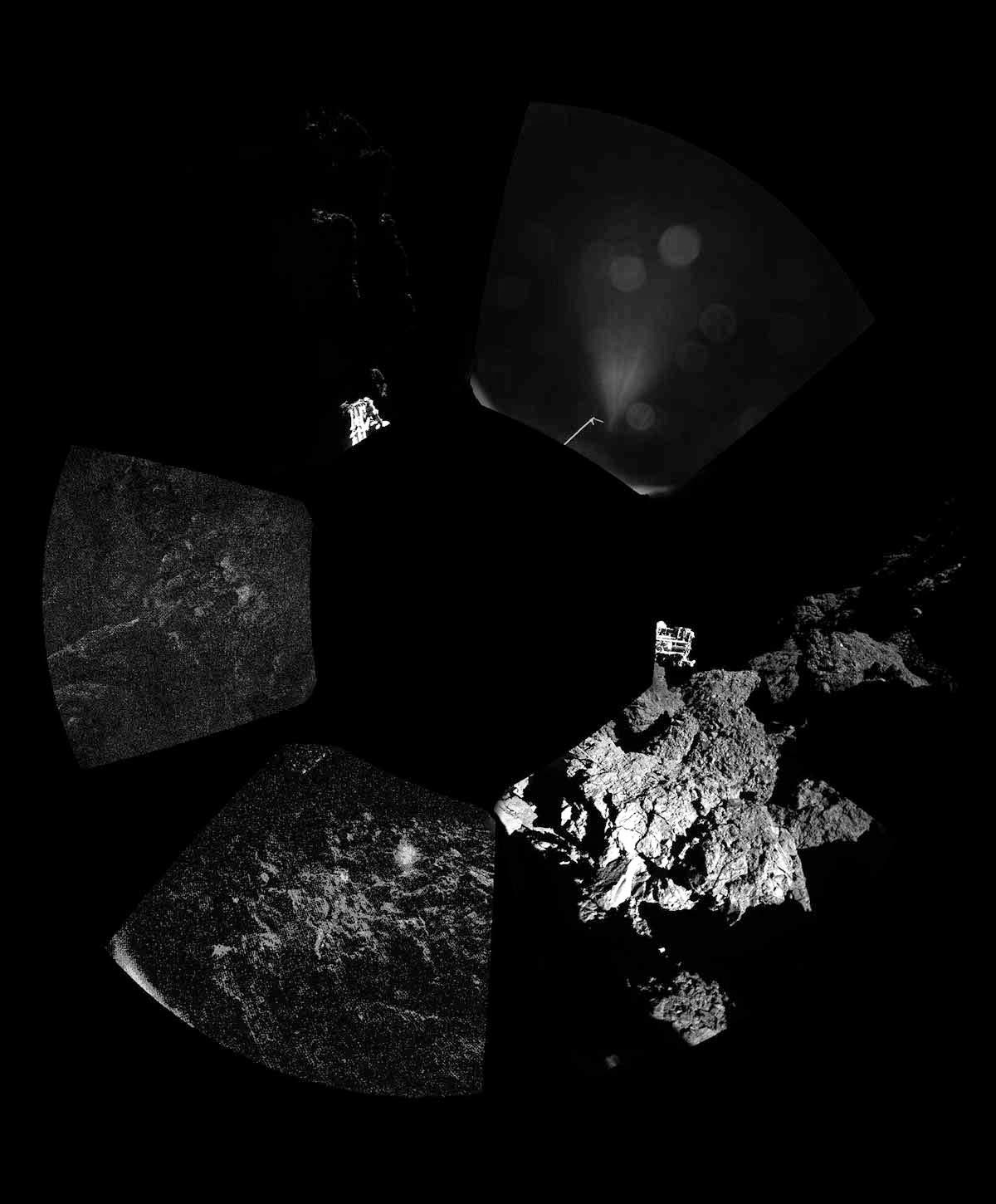

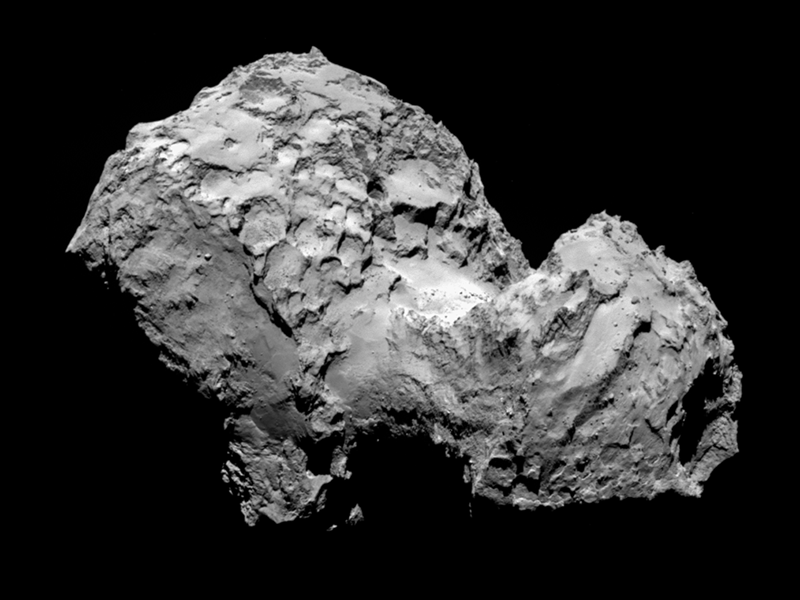

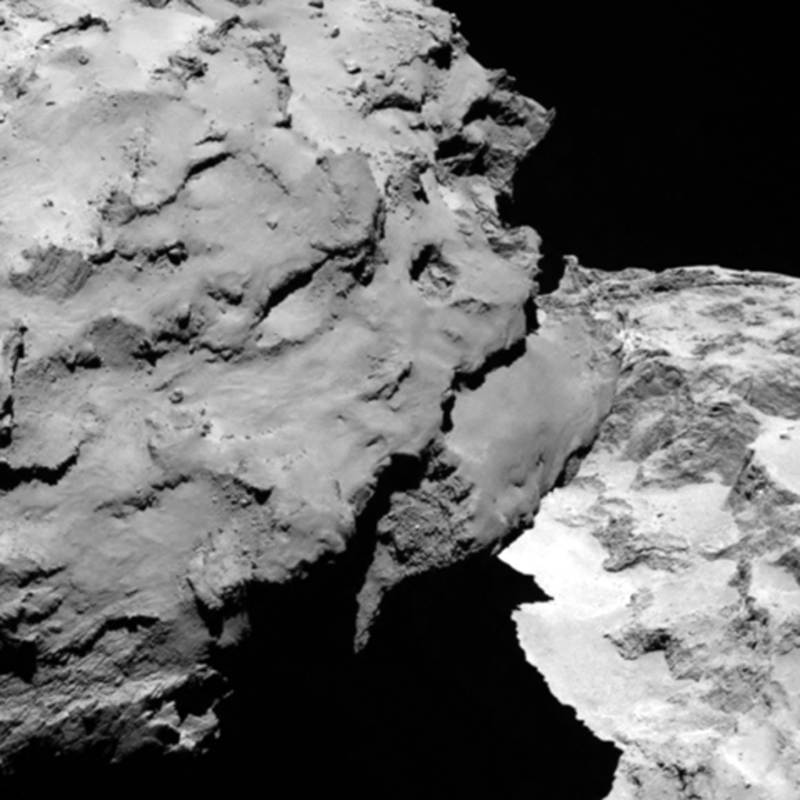

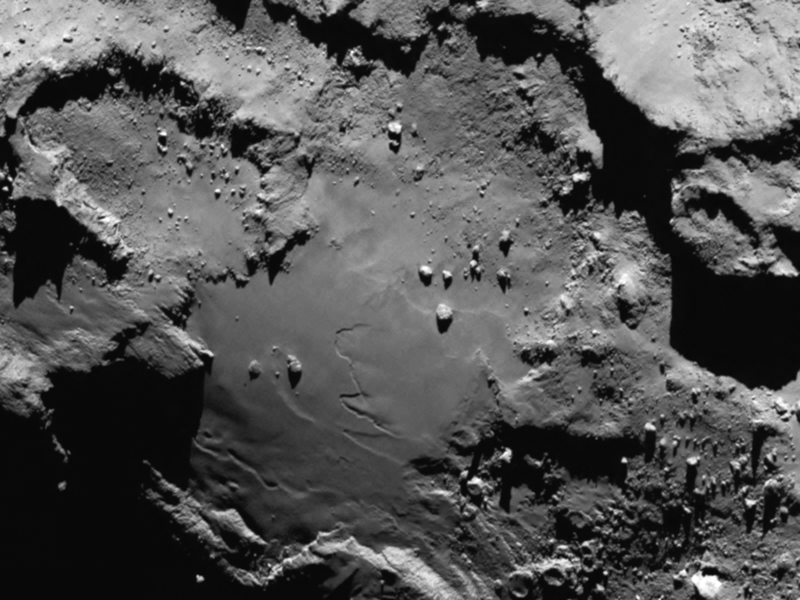

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

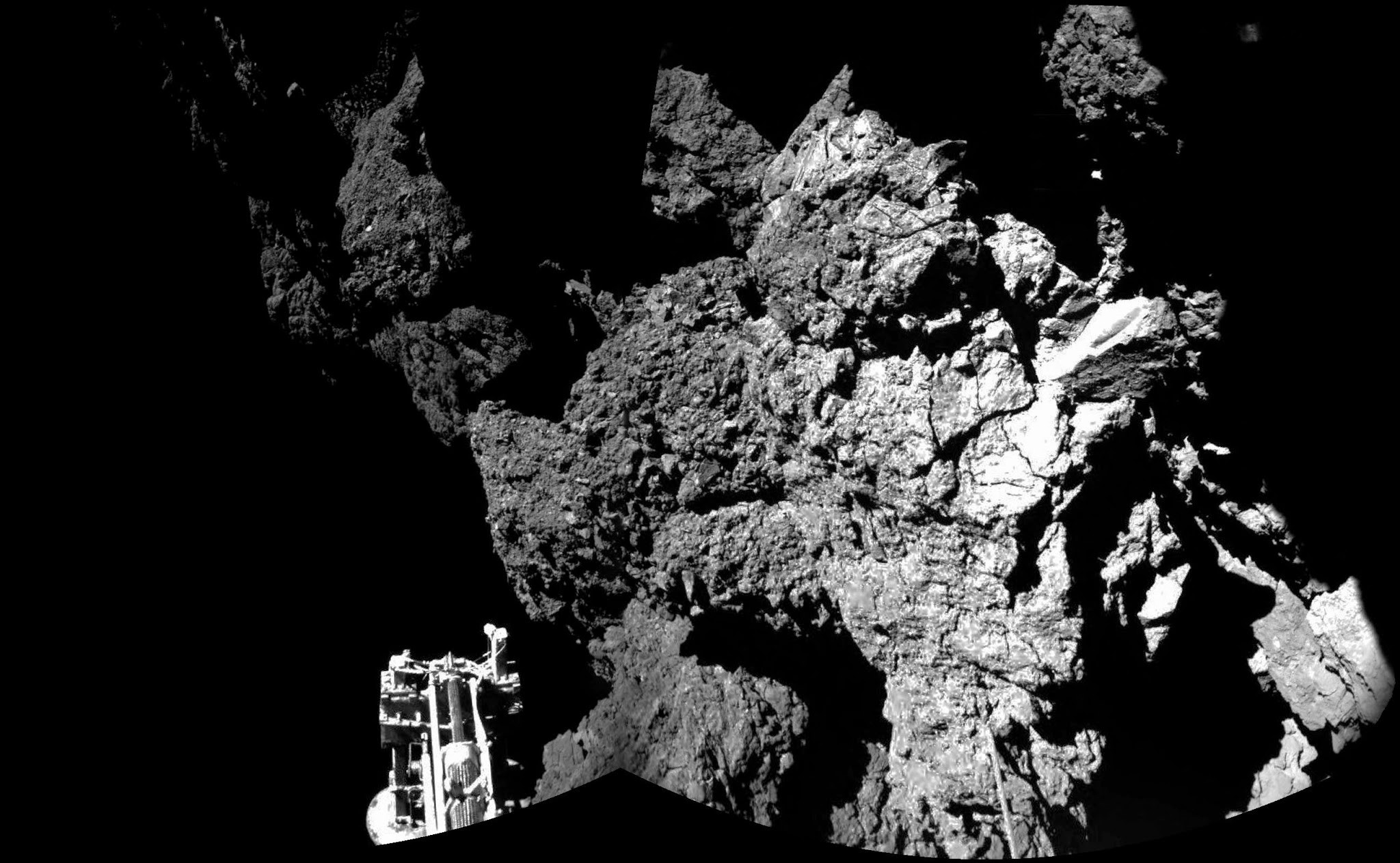

[Image: Comet 67P, via  [Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via

[Image: The irregular terrain of Comet 67P, via  [Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Comet 67P, via

[Image: Screen grab via

[Image: Screen grab via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image: Screen grabs via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

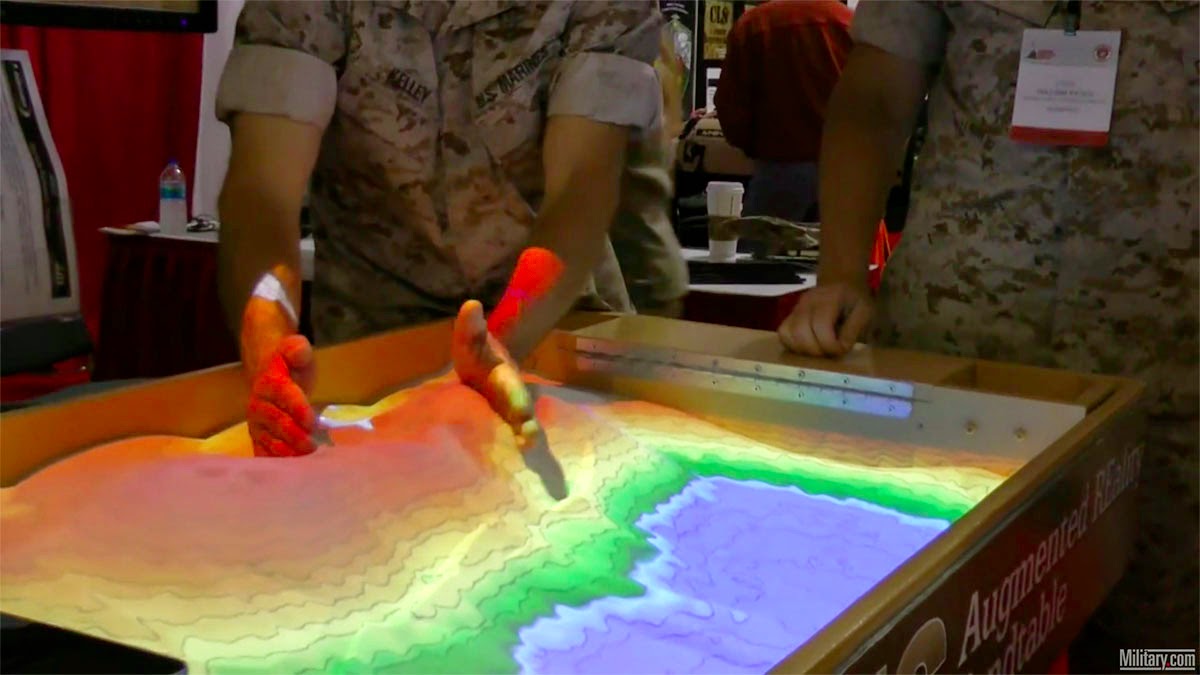

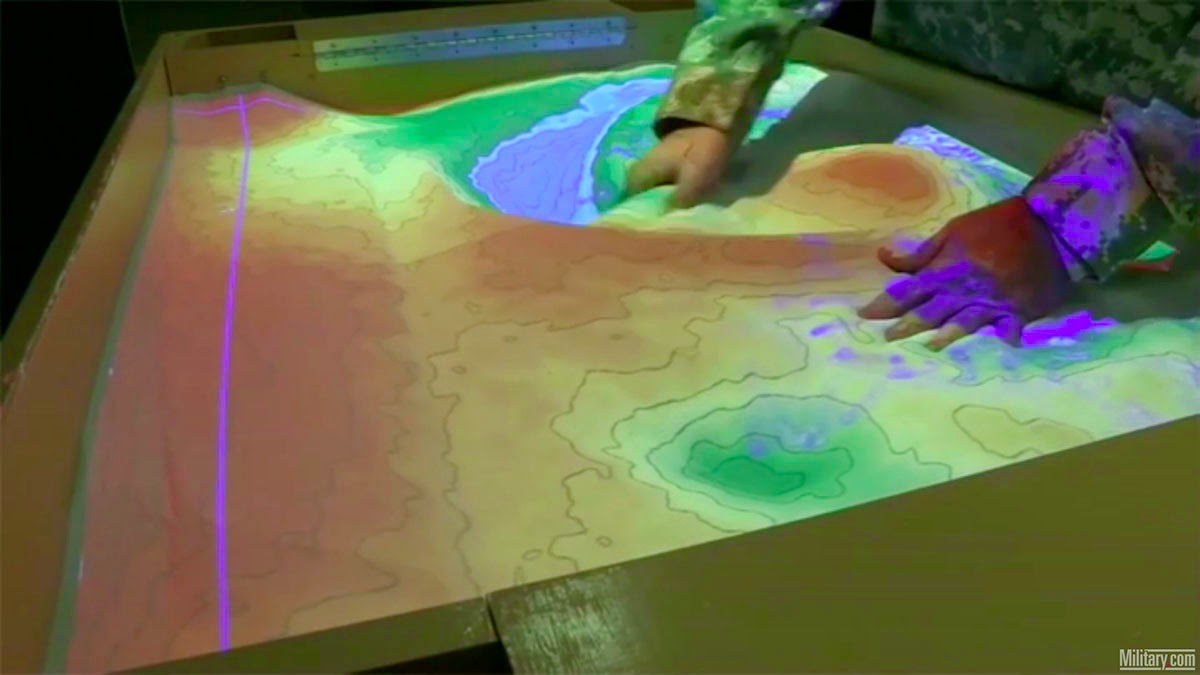

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:  [Images:

[Images:

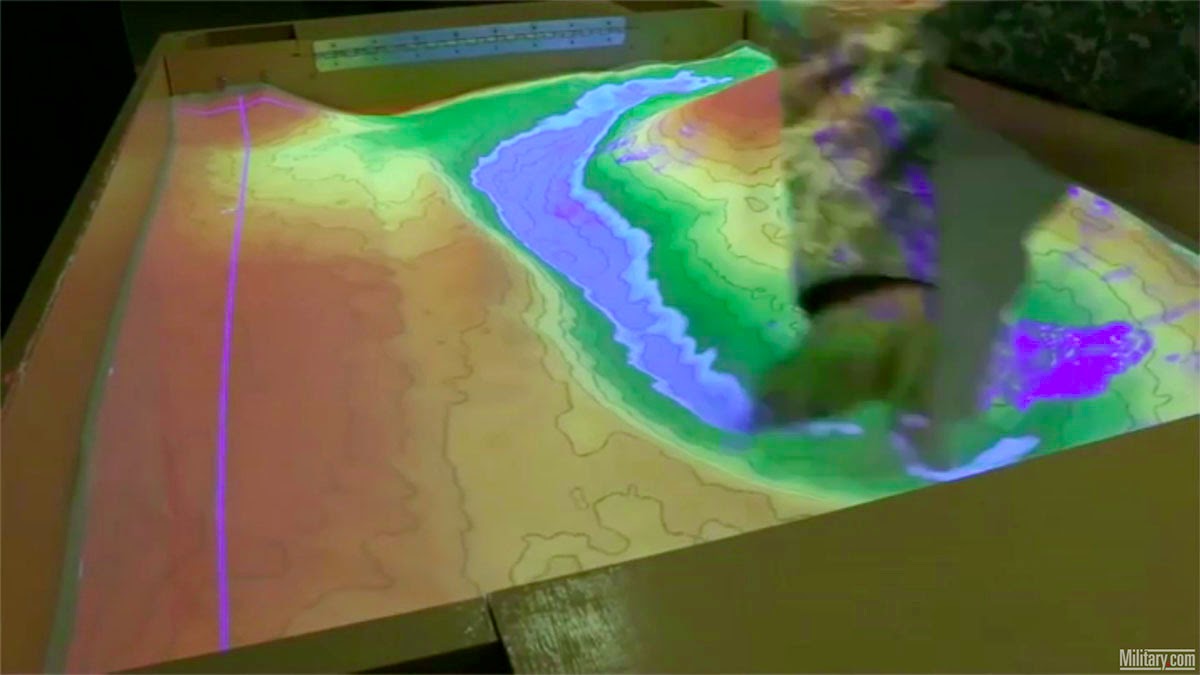

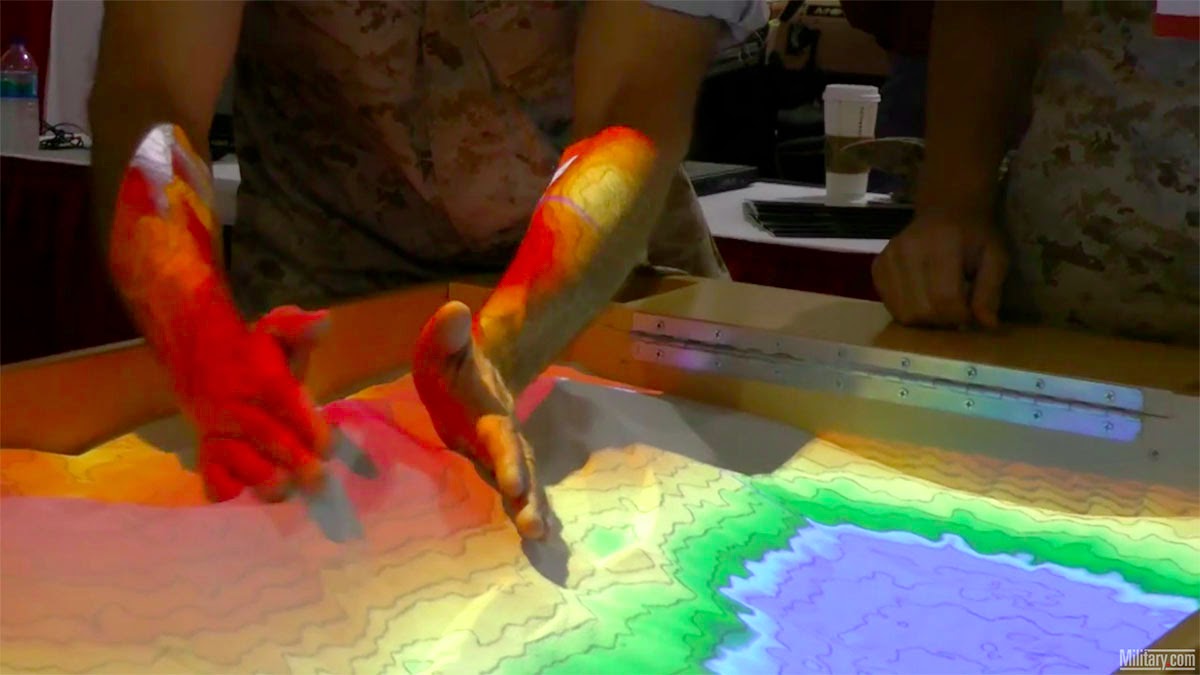

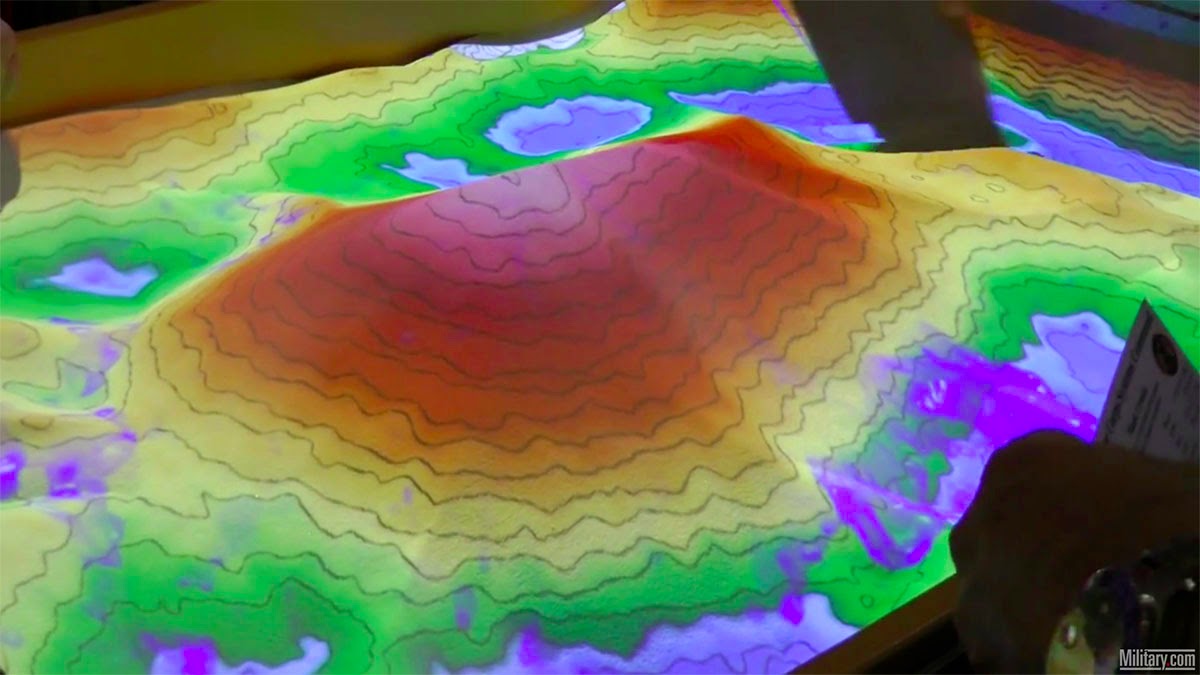

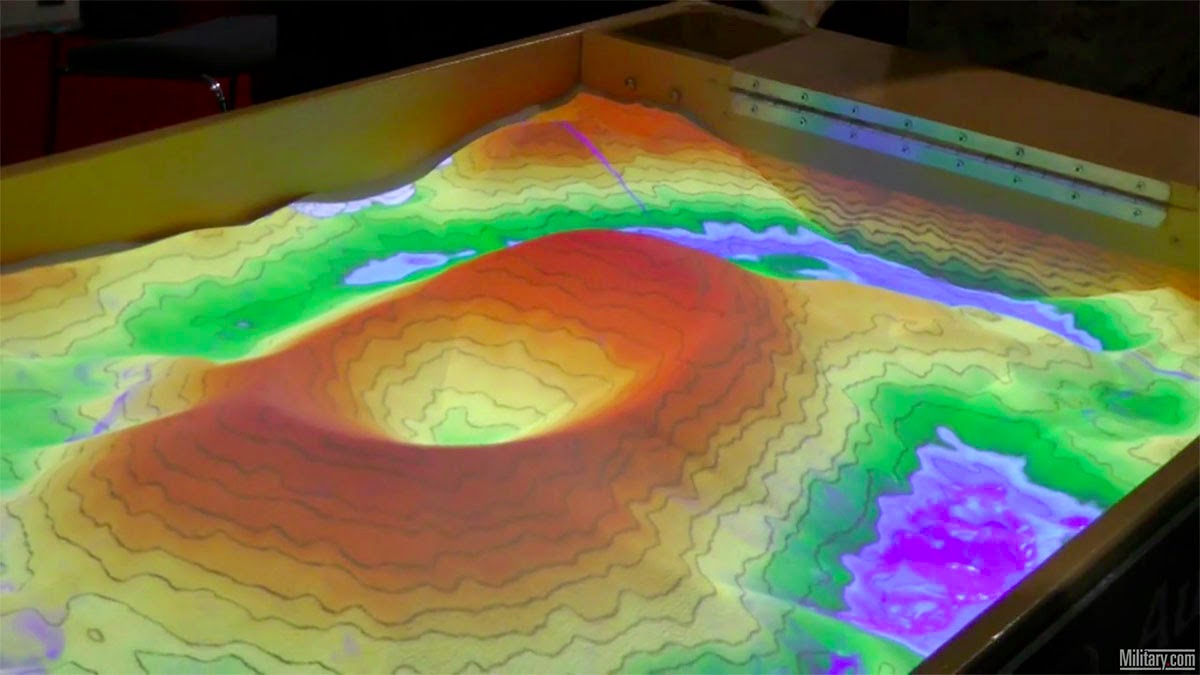

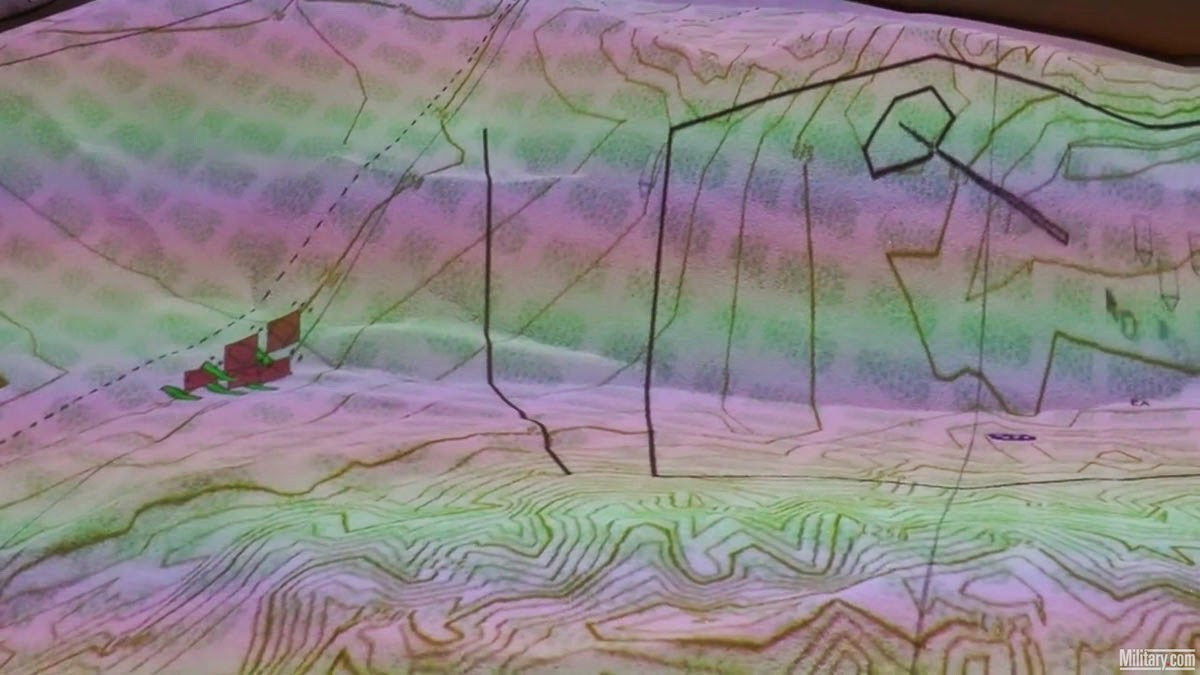

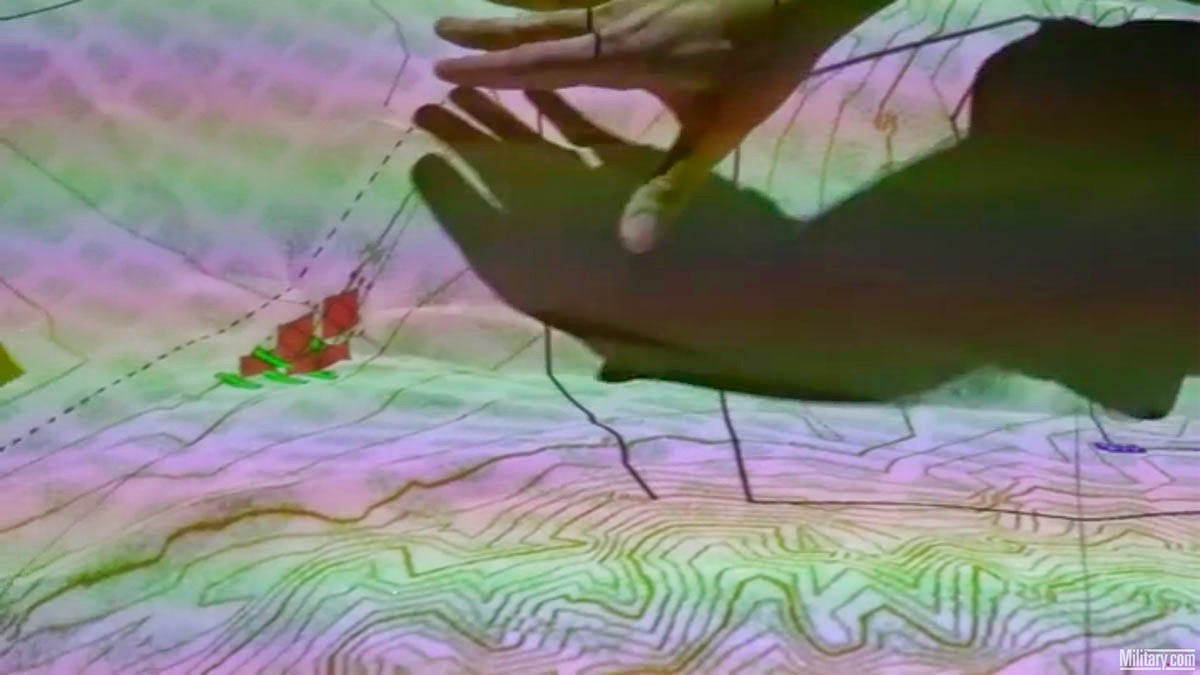

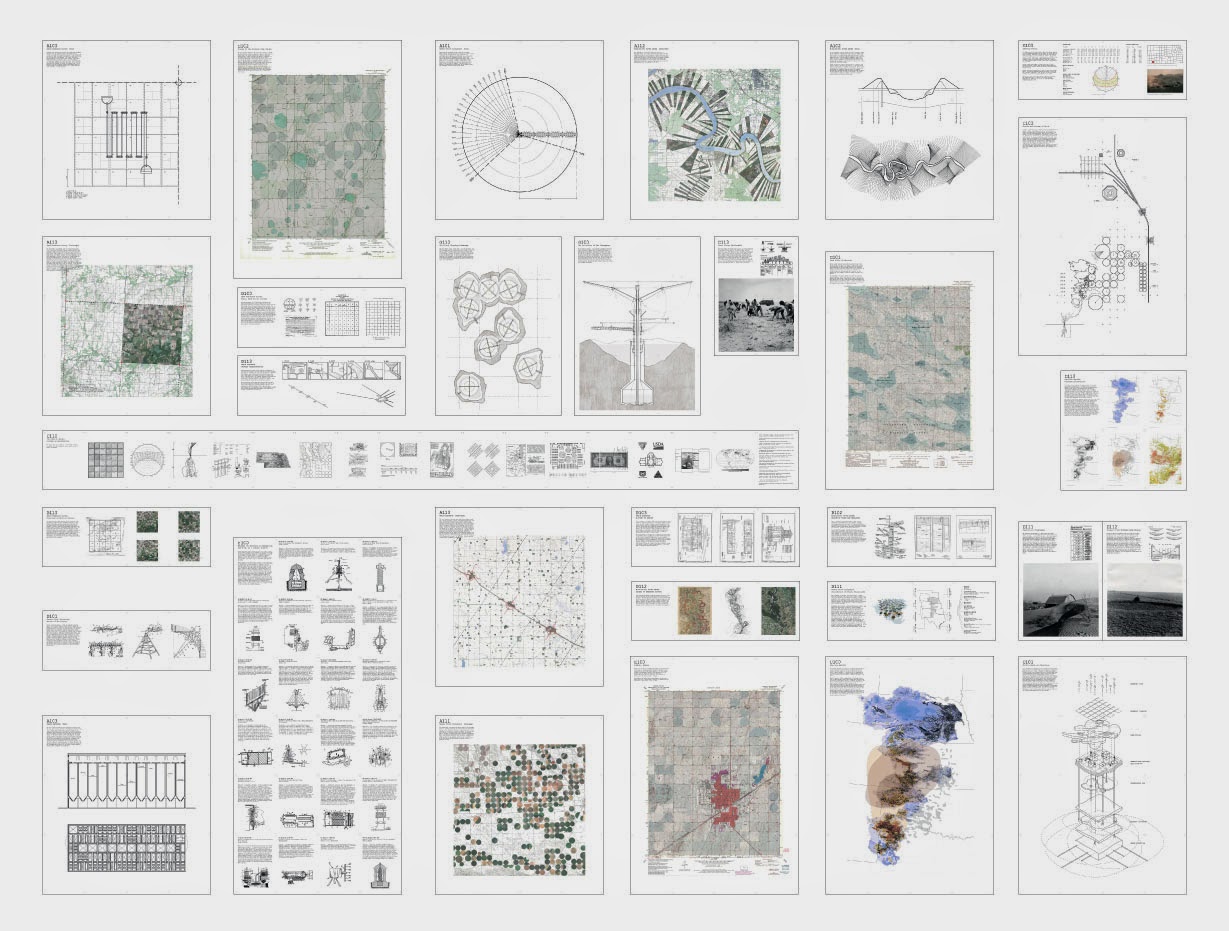

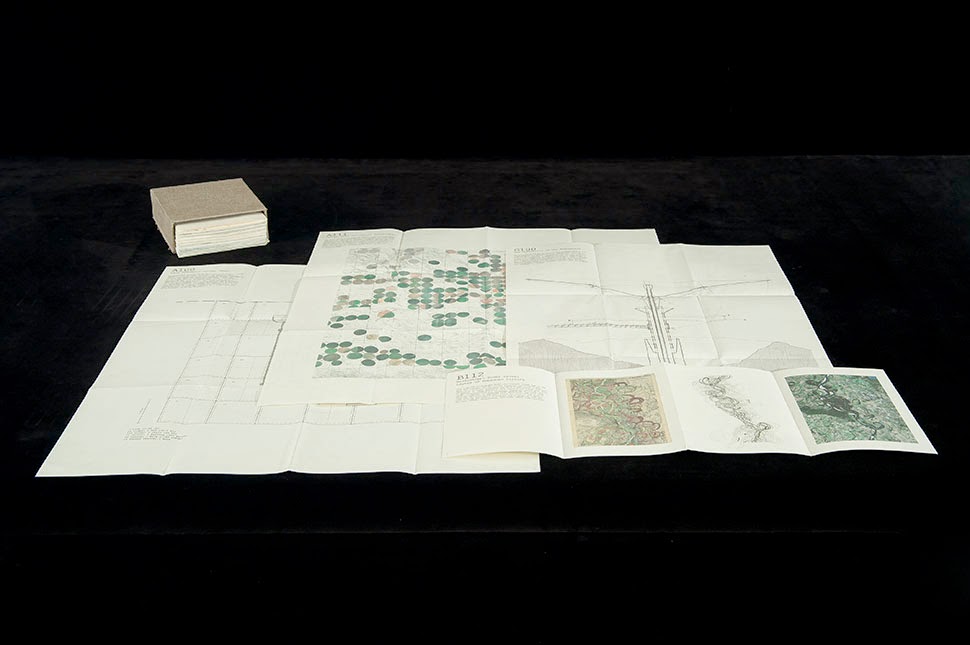

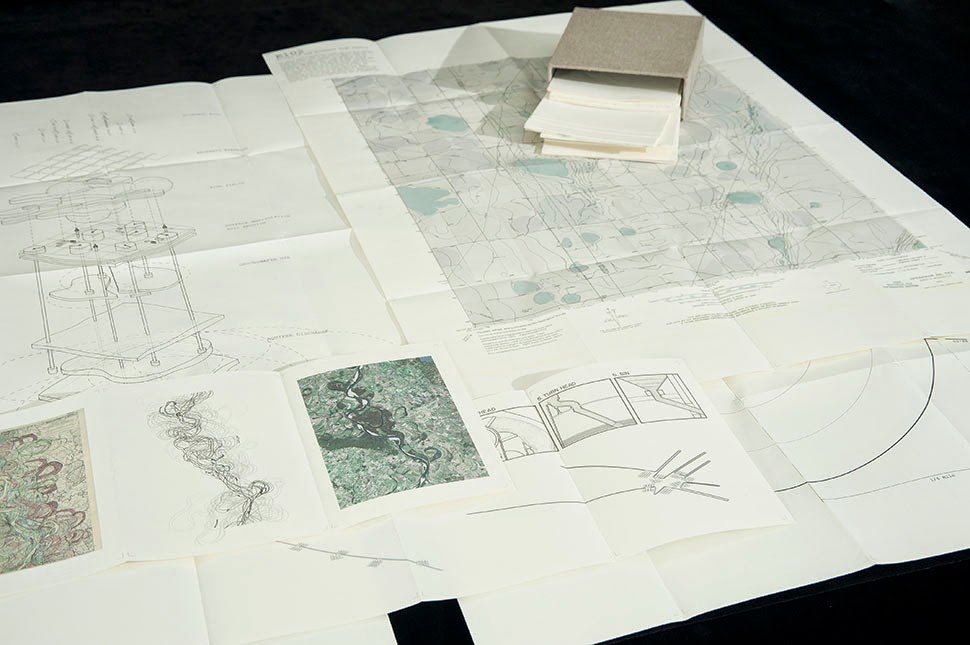

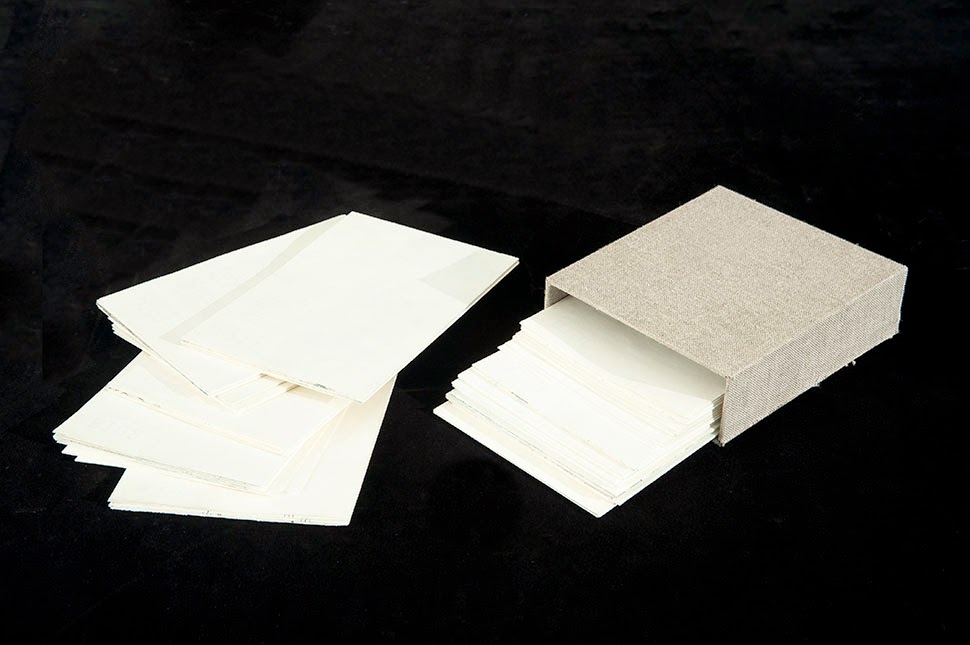

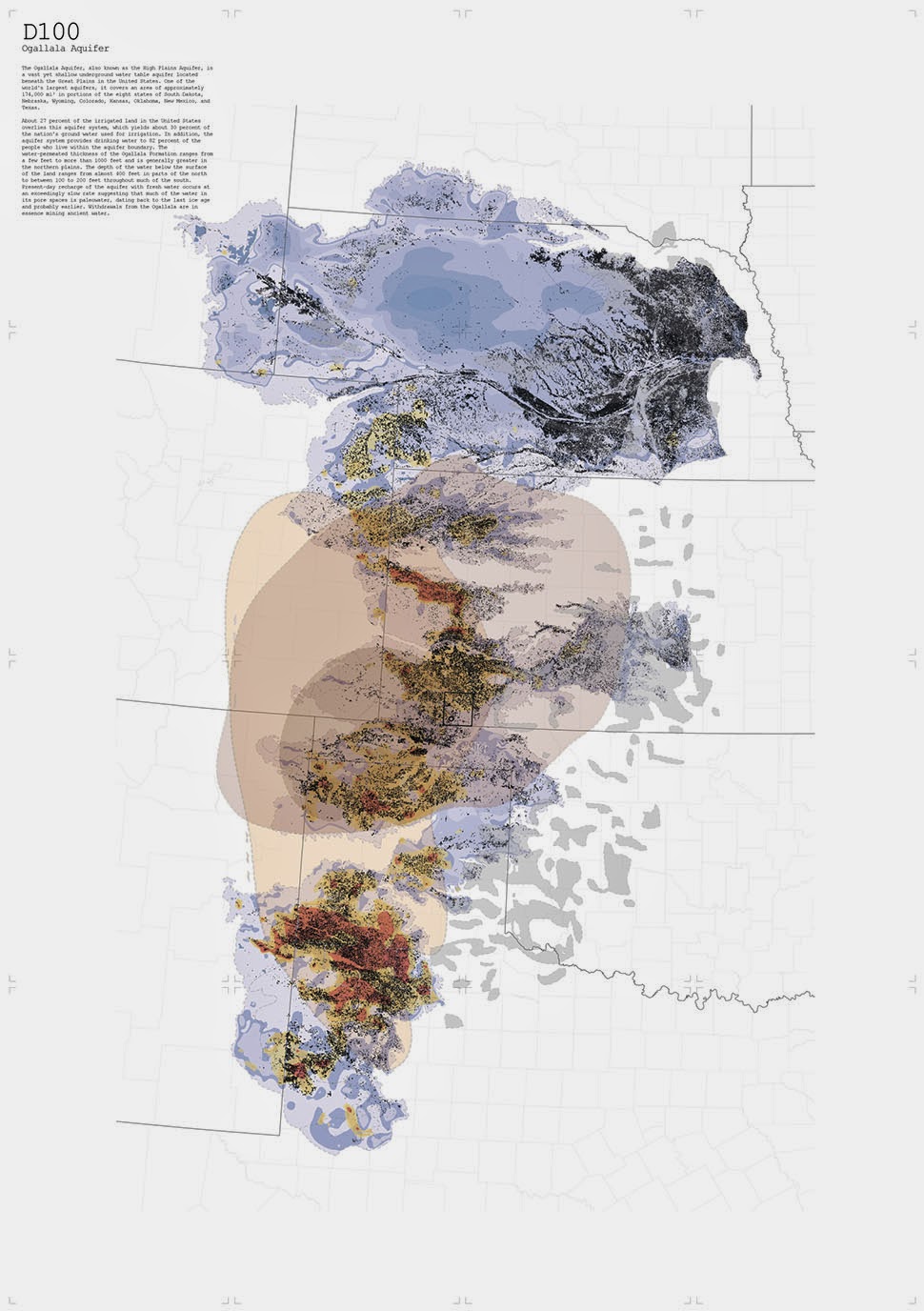

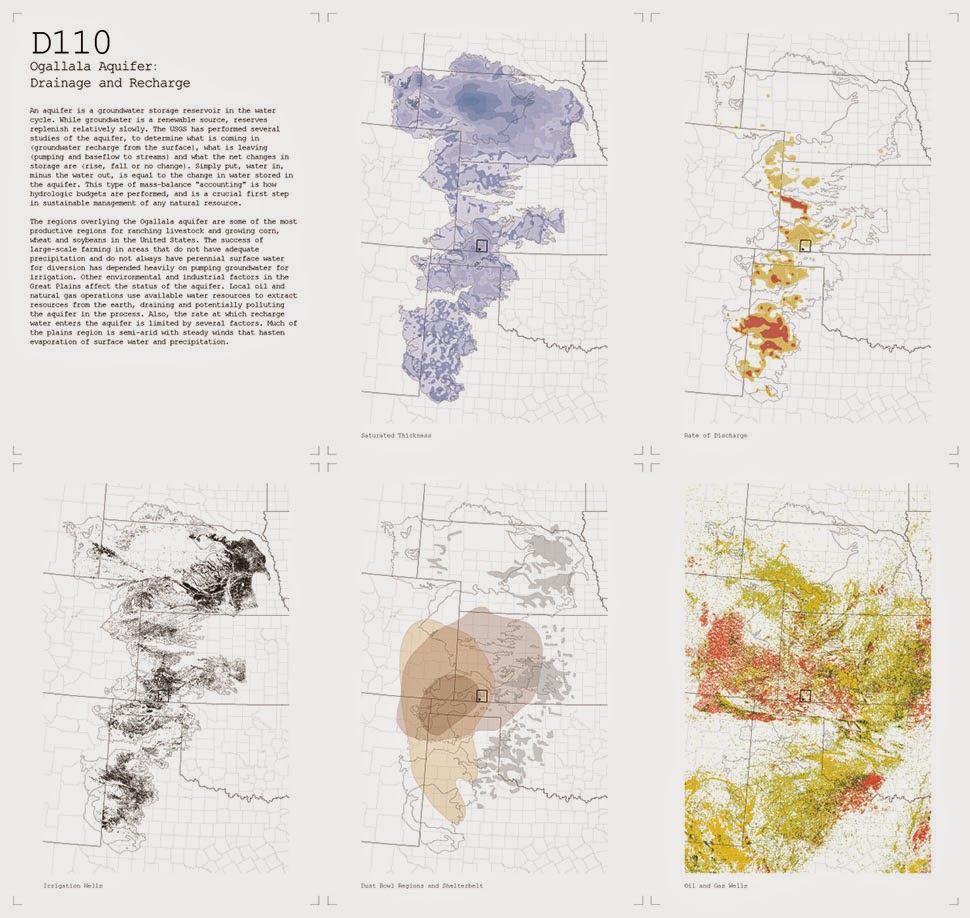

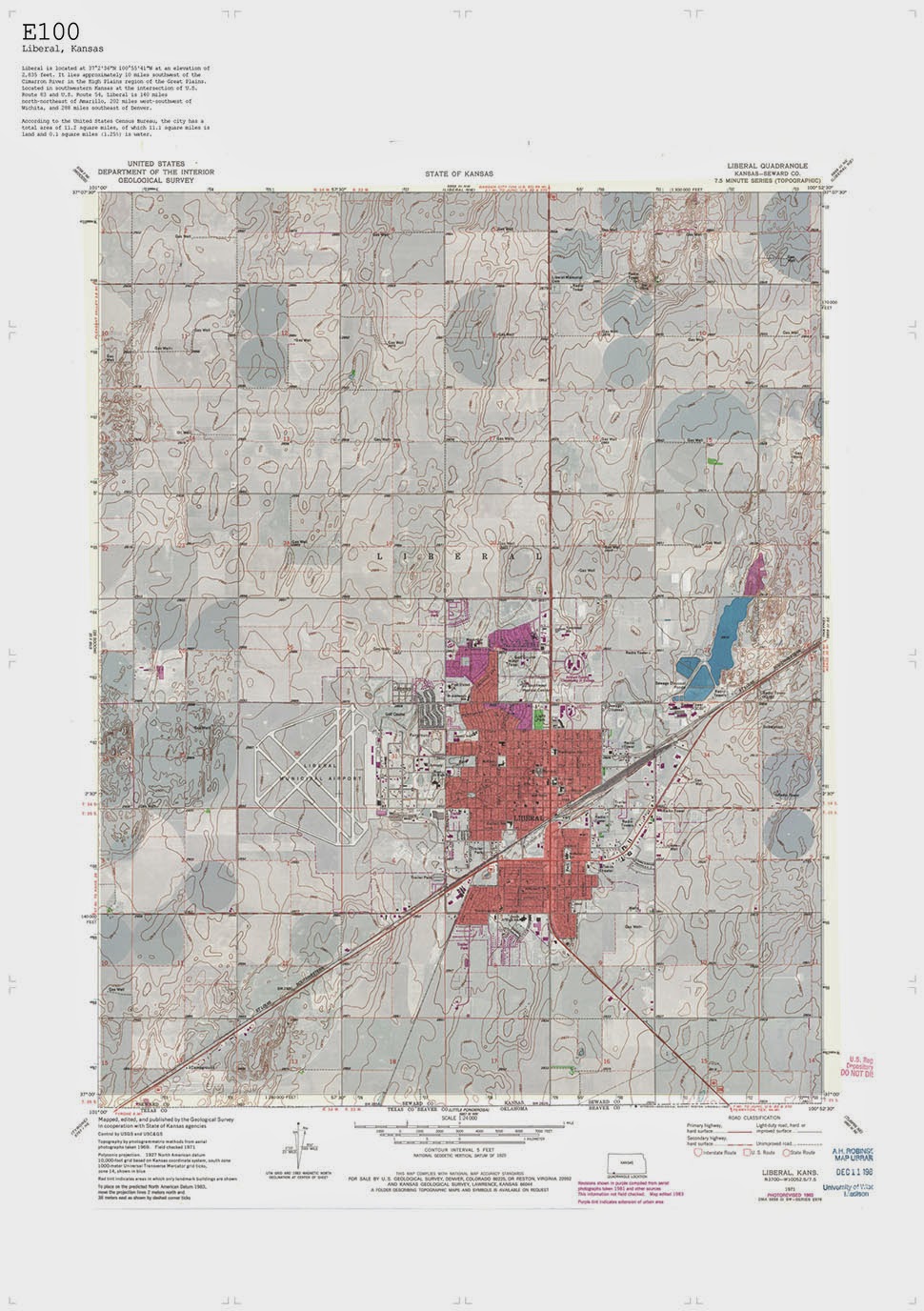

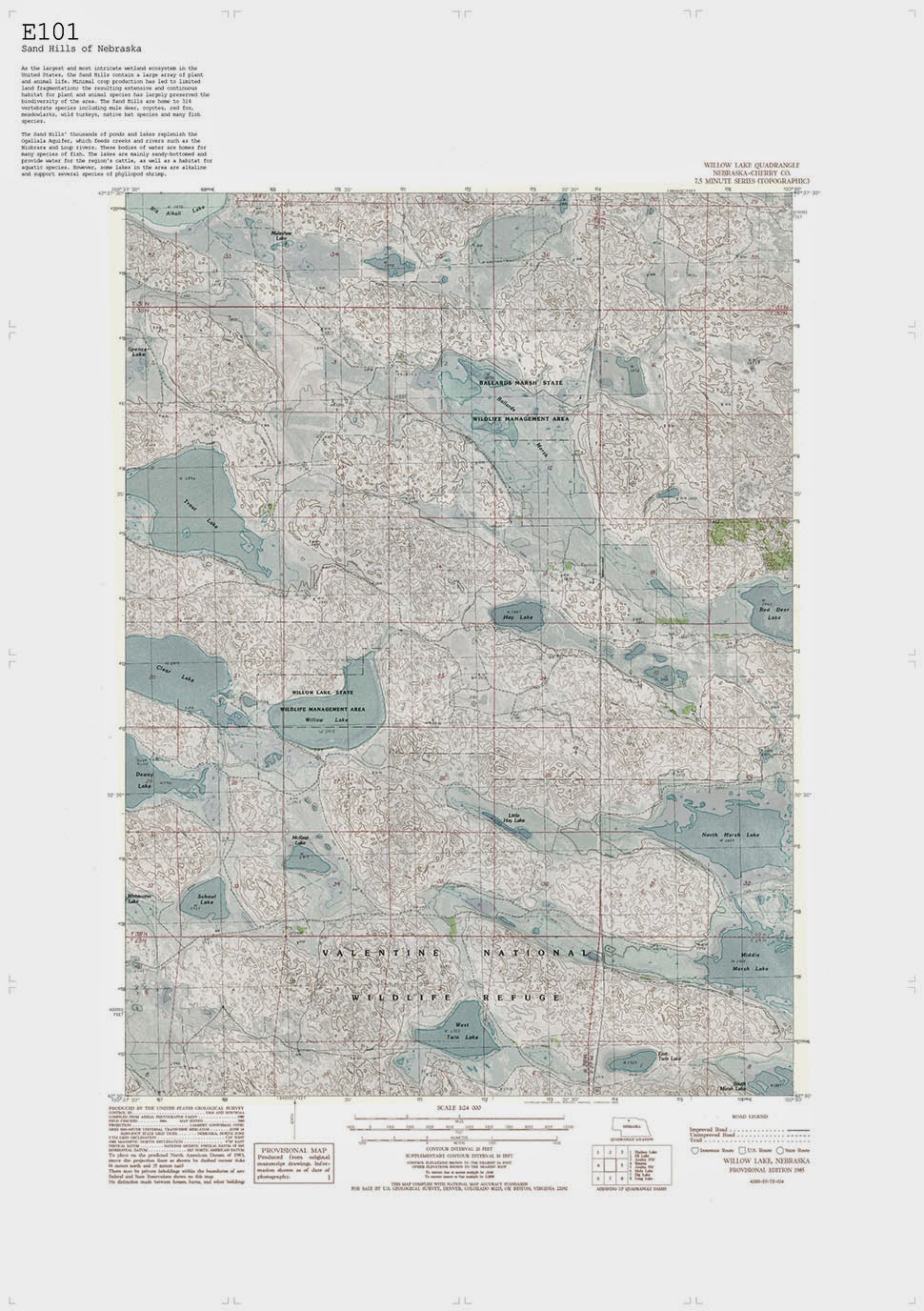

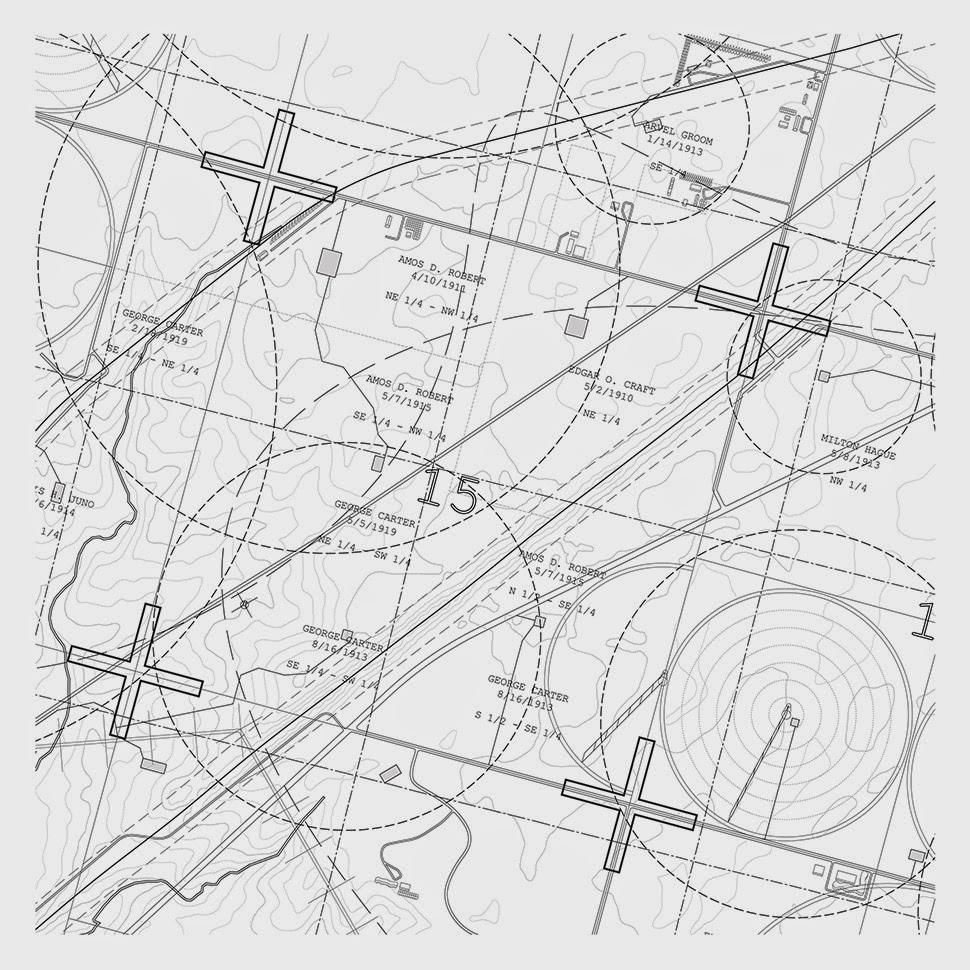

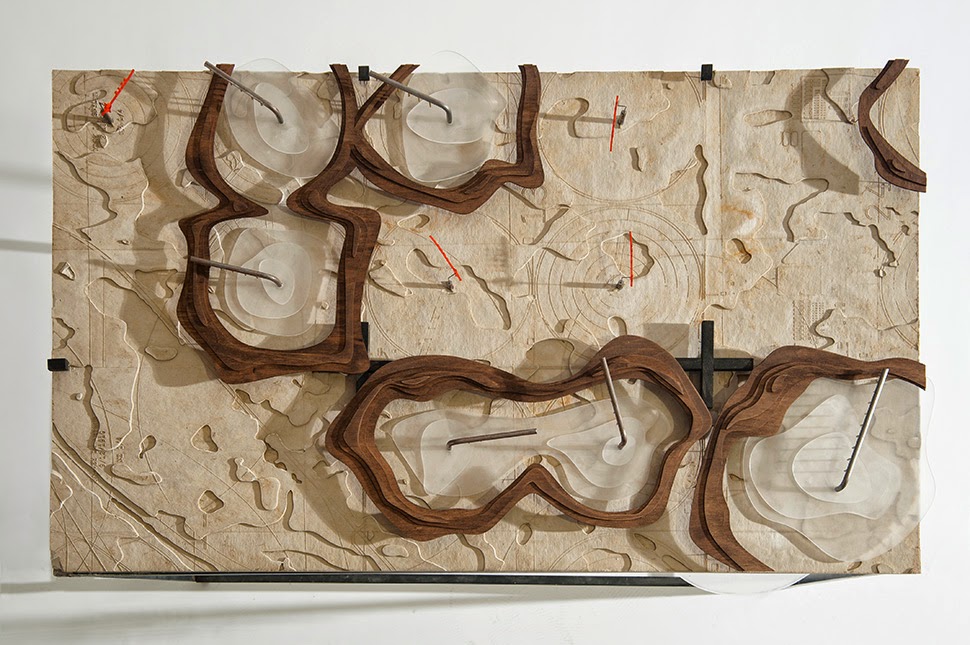

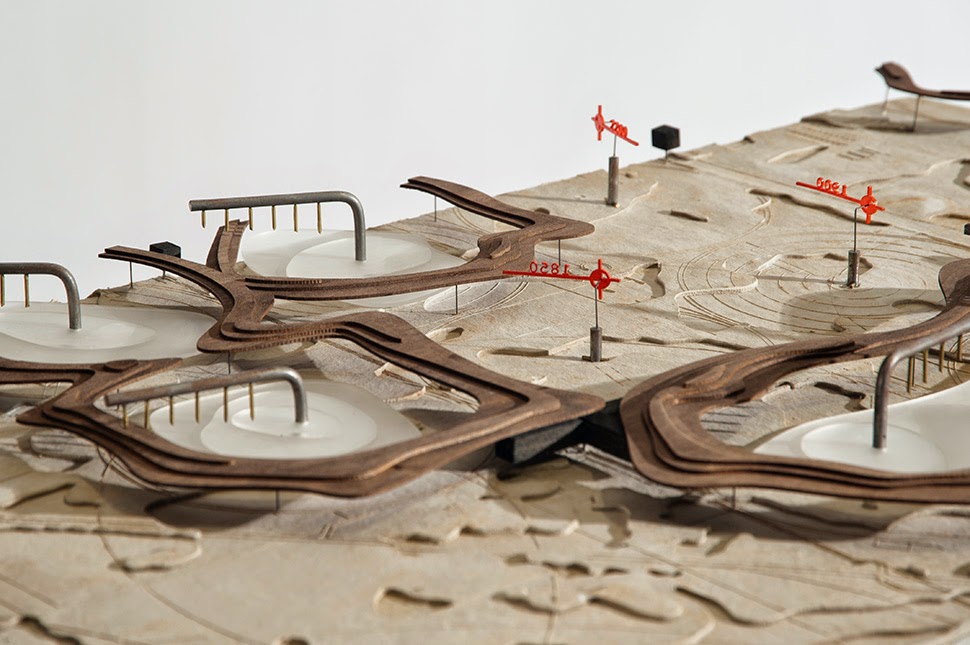

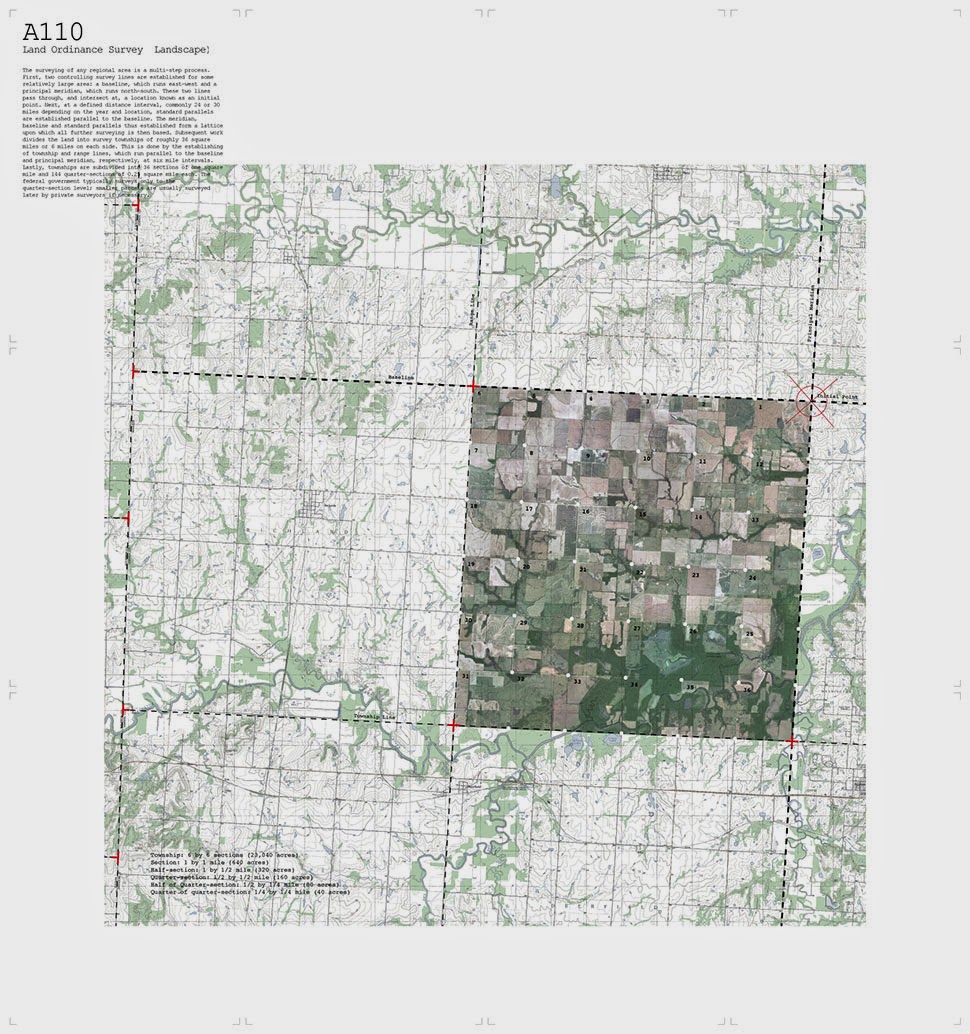

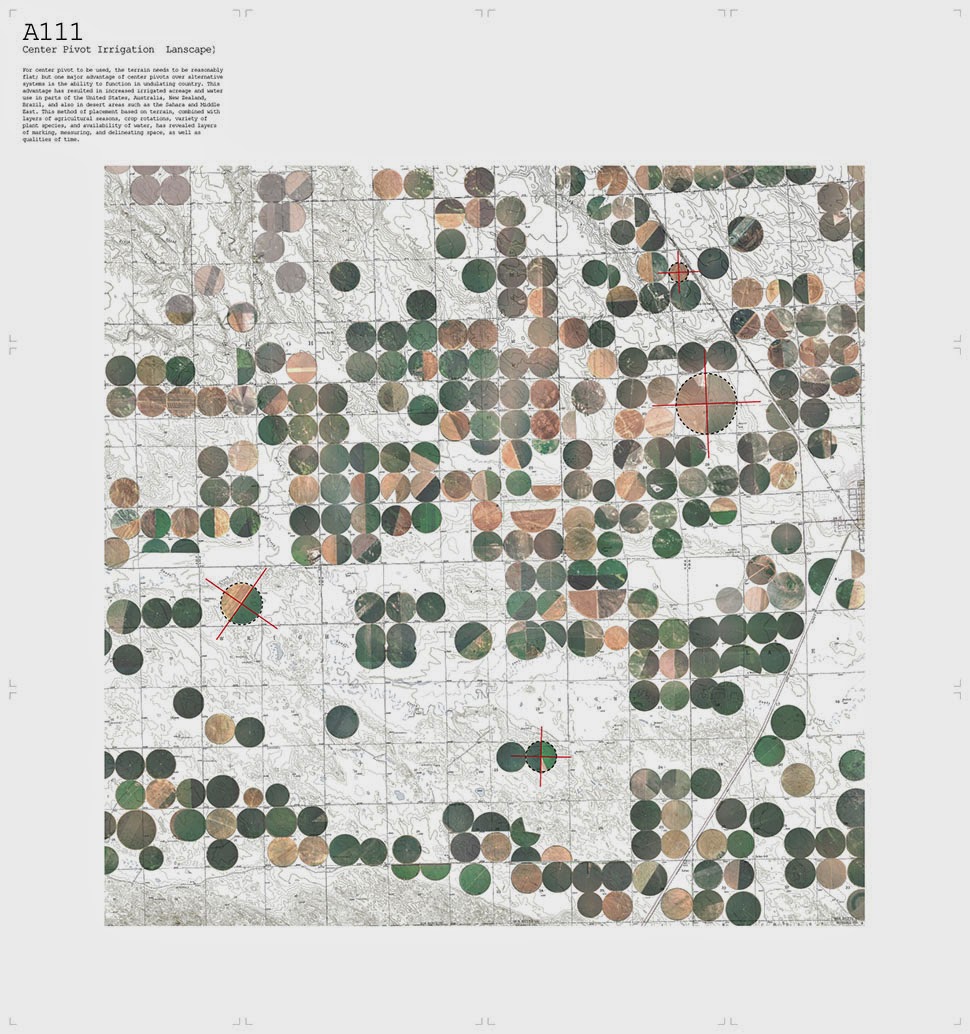

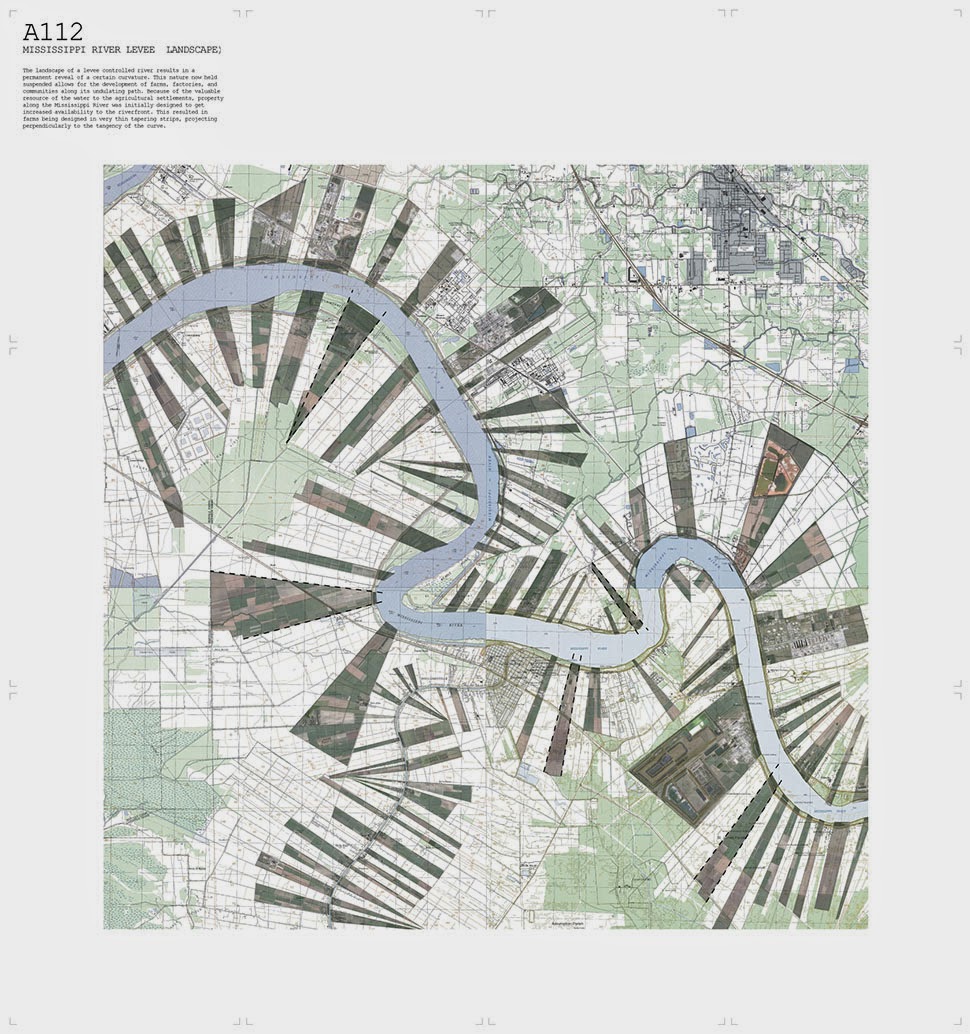

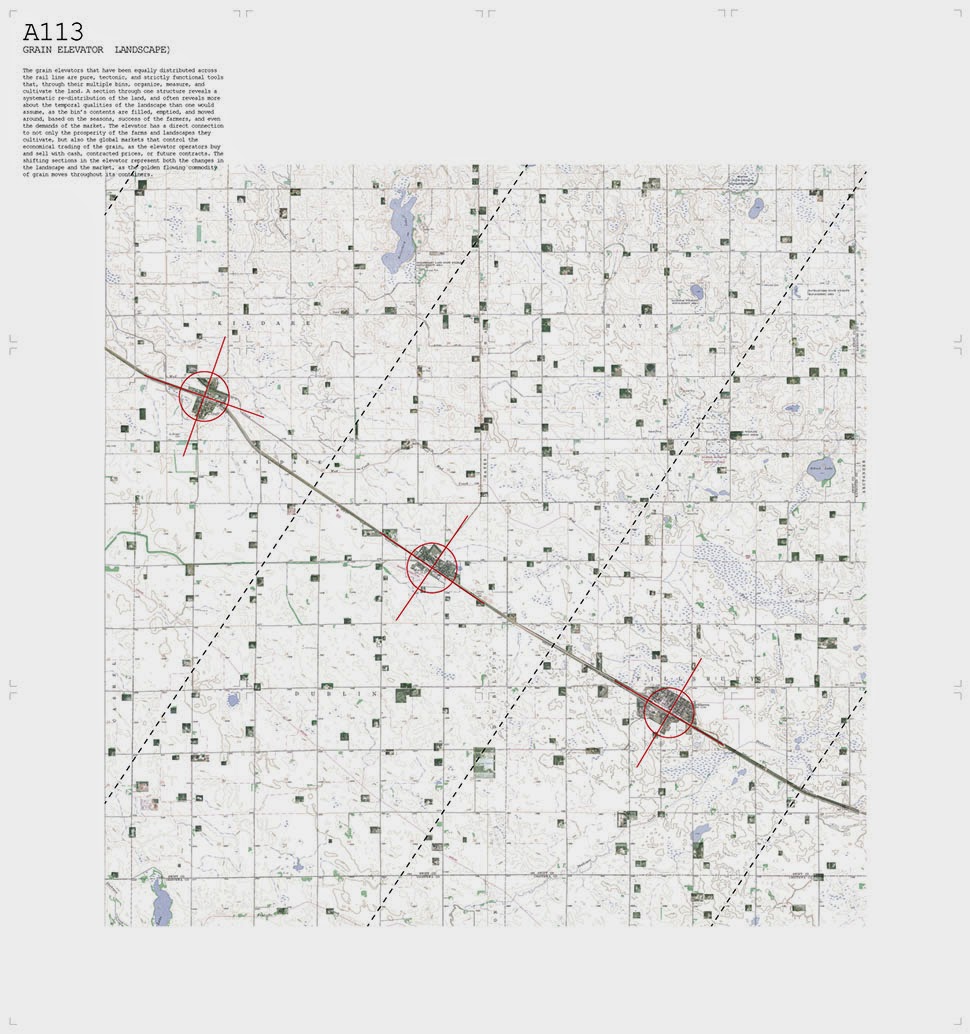

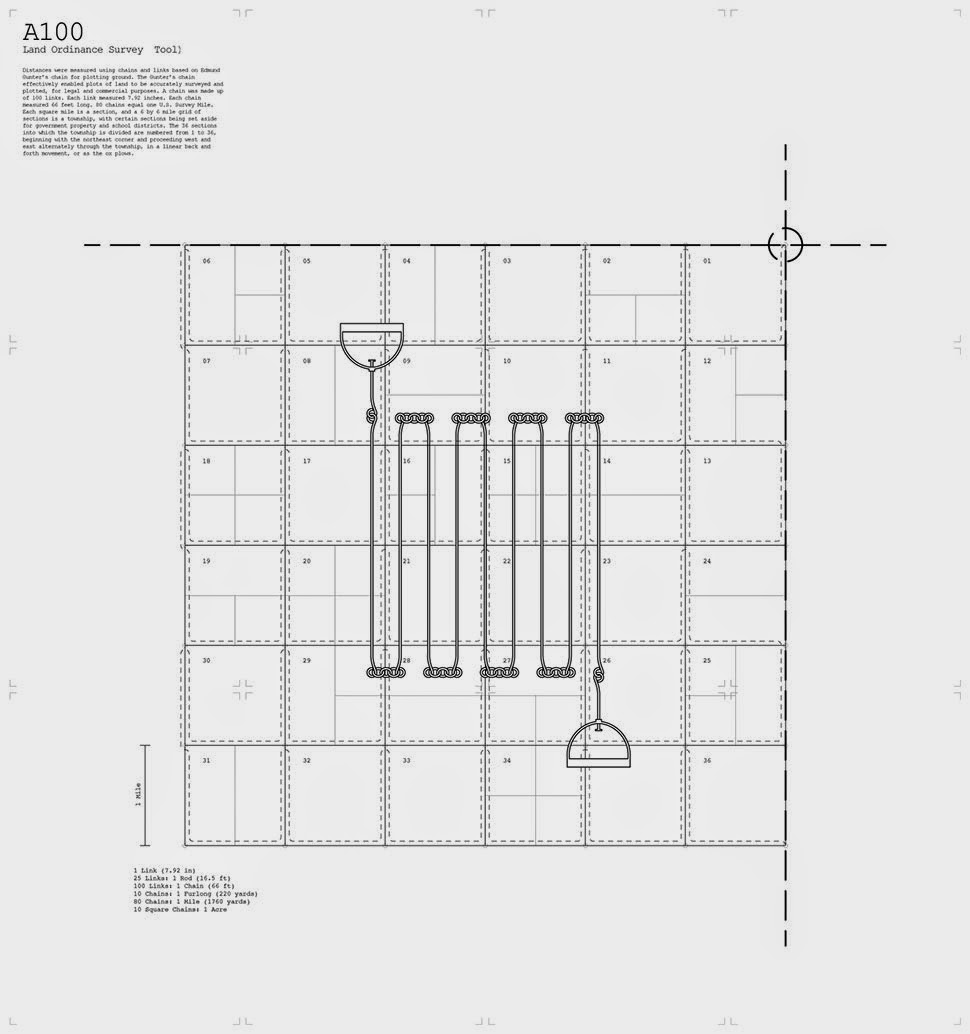

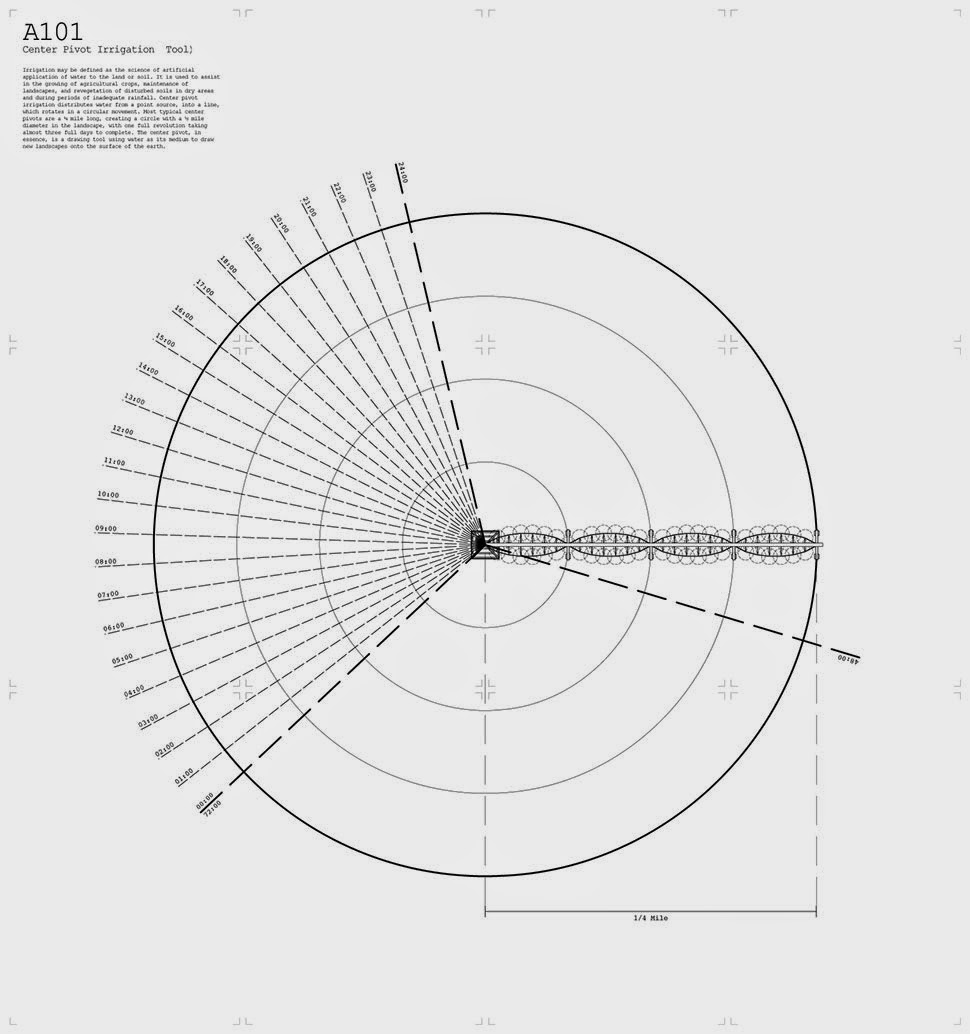

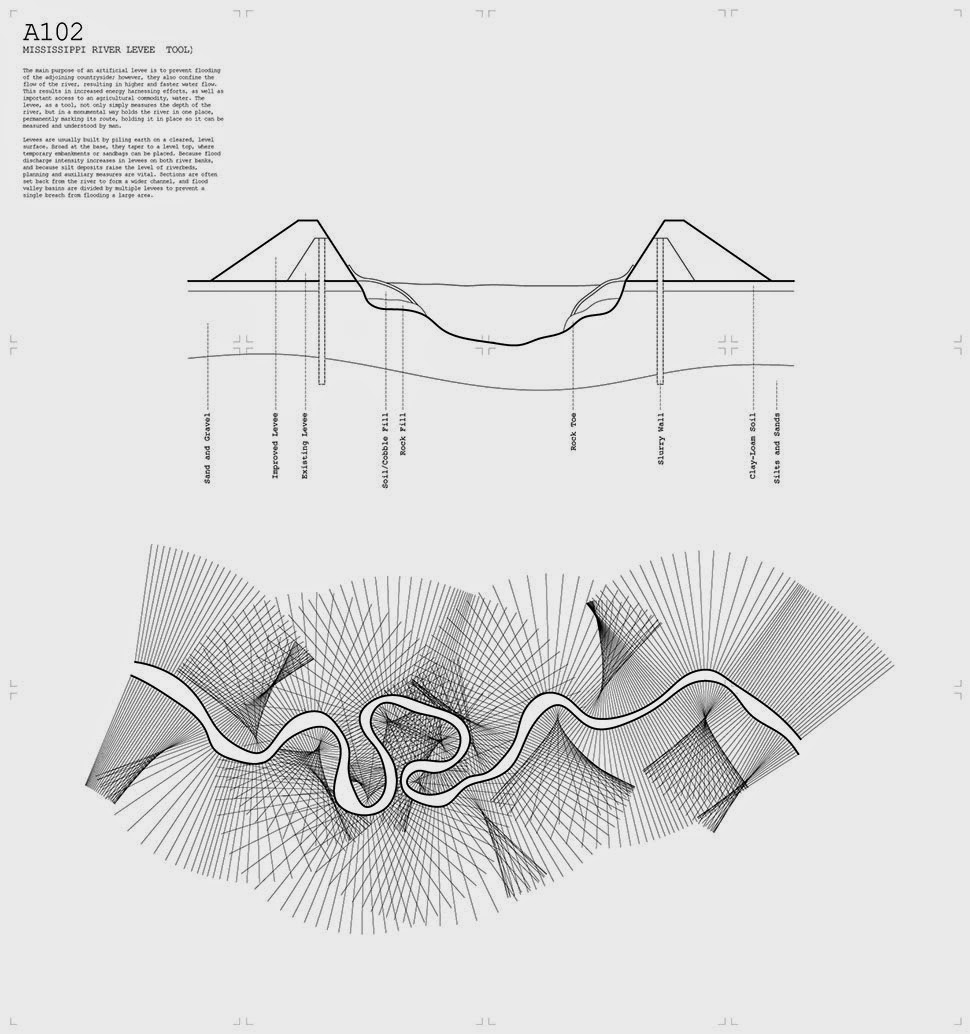

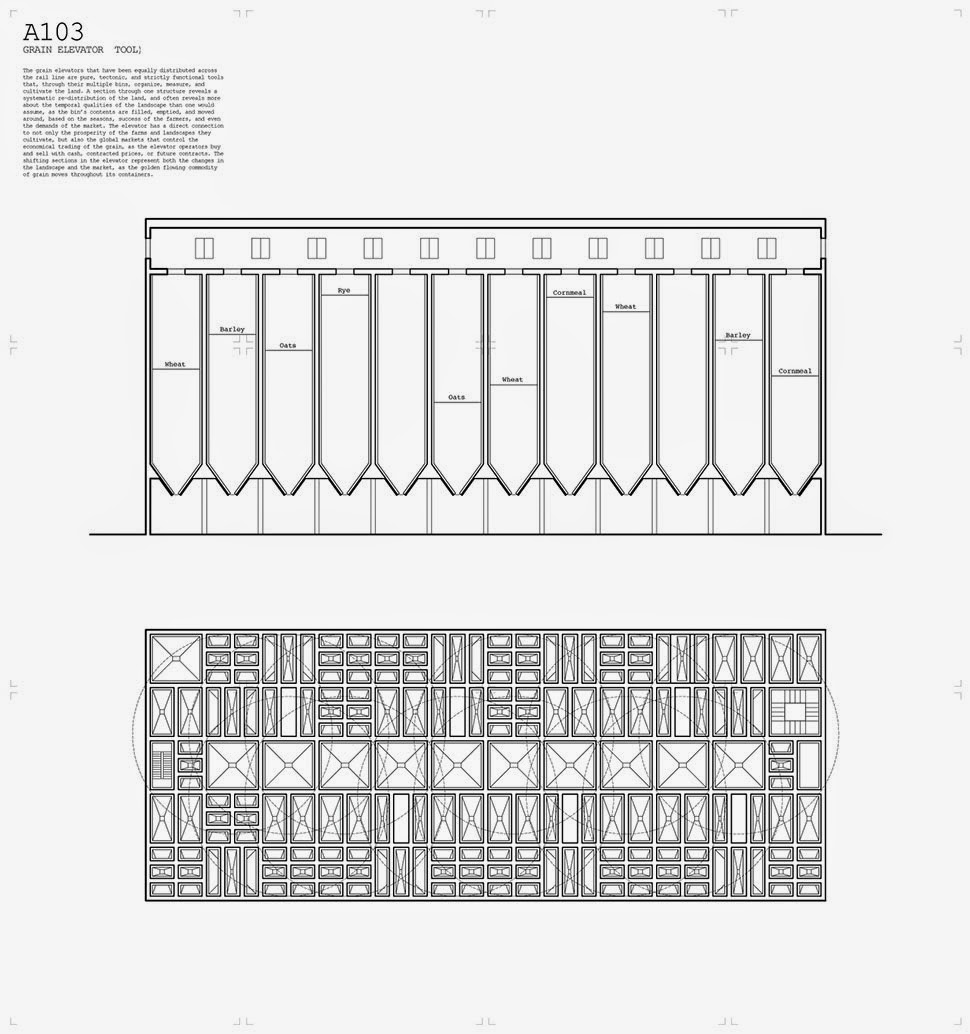

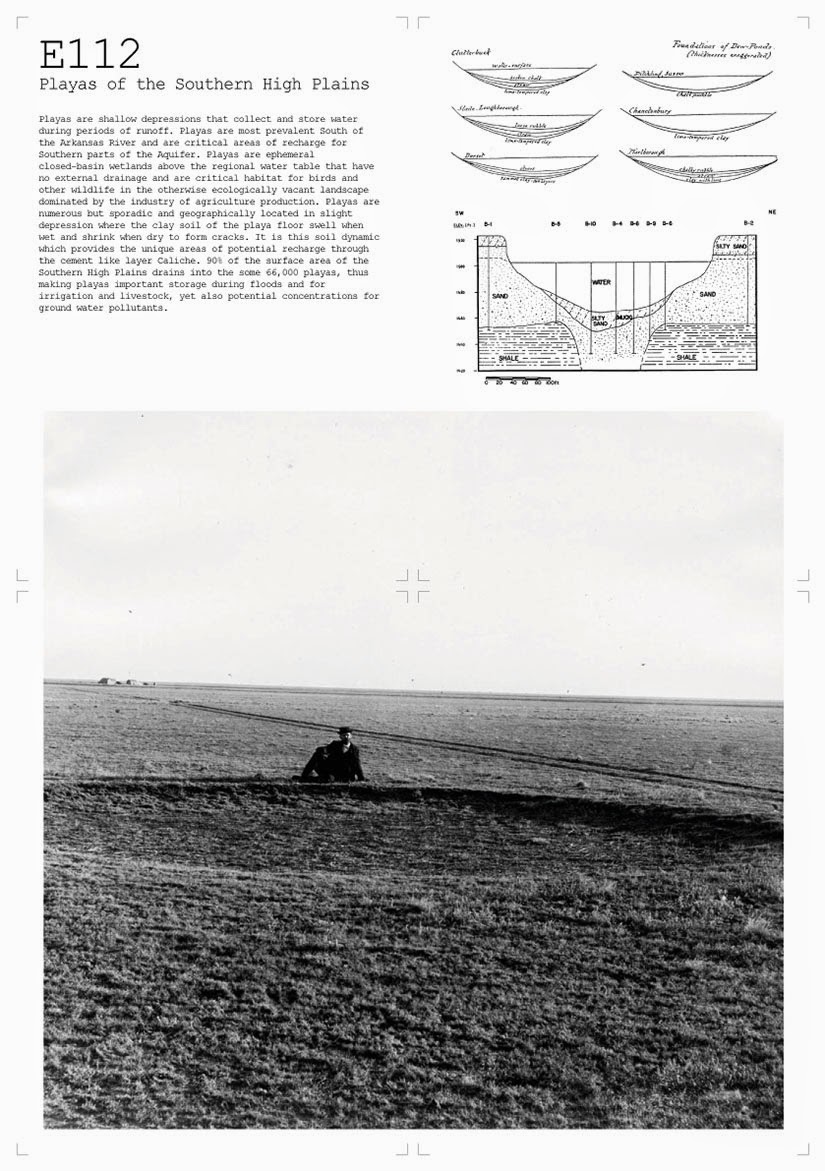

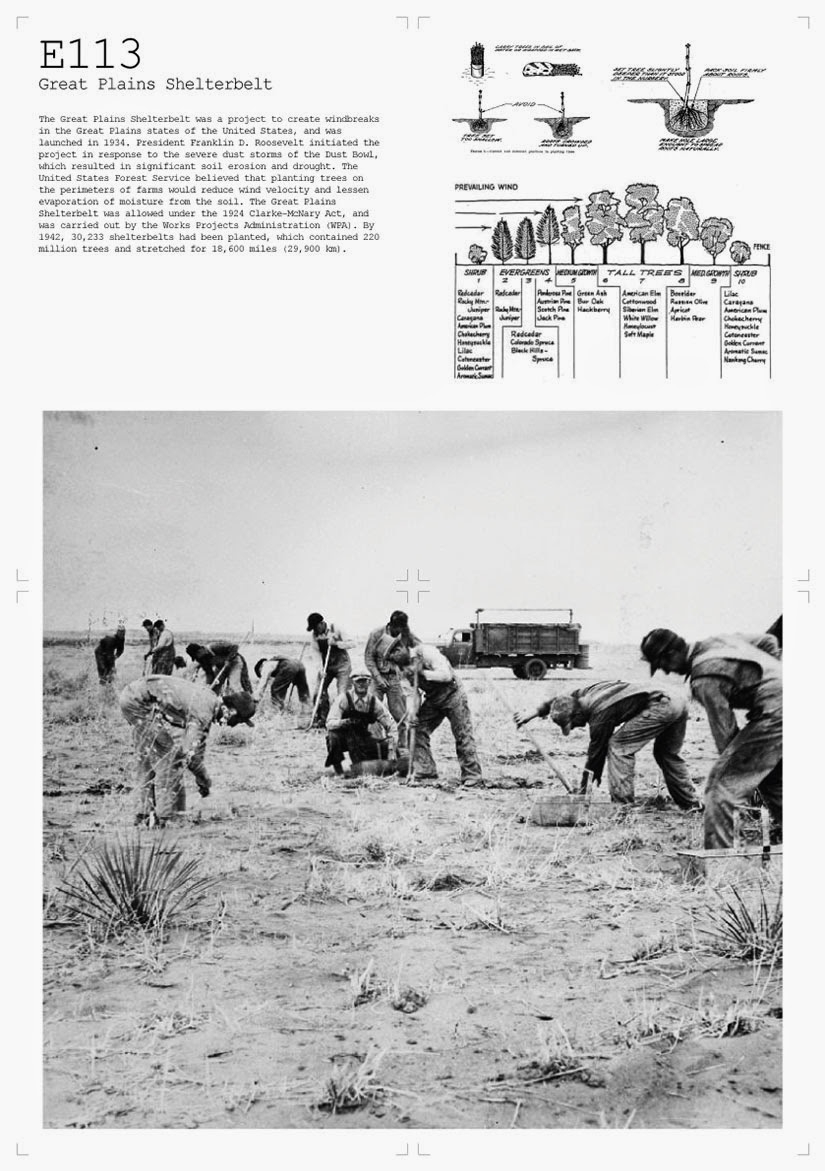

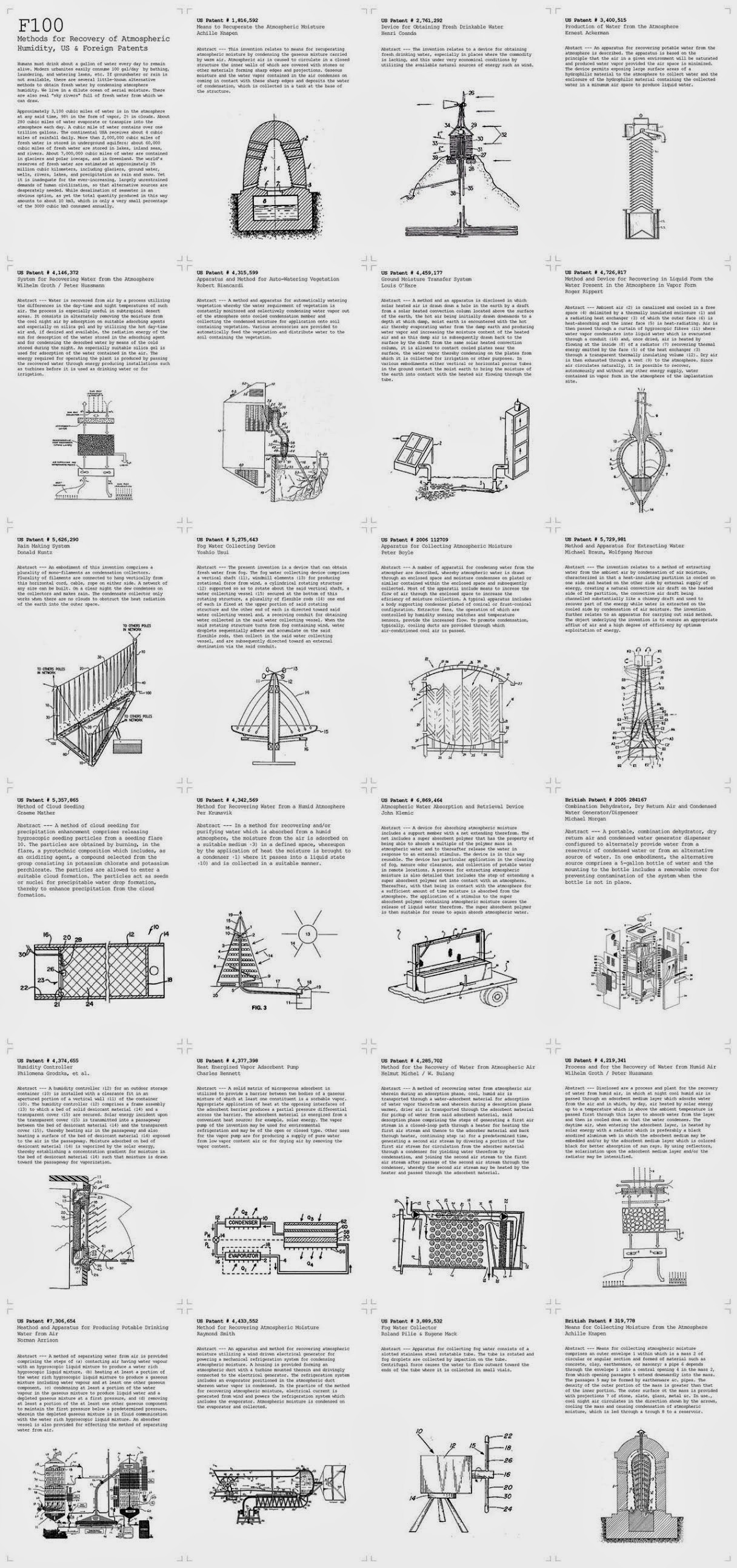

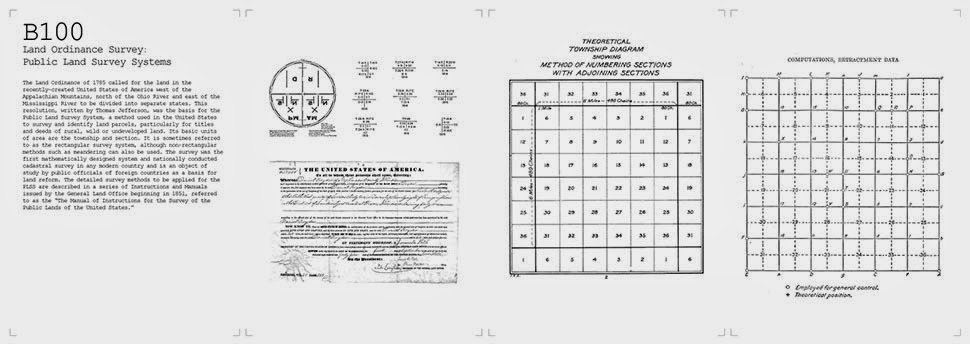

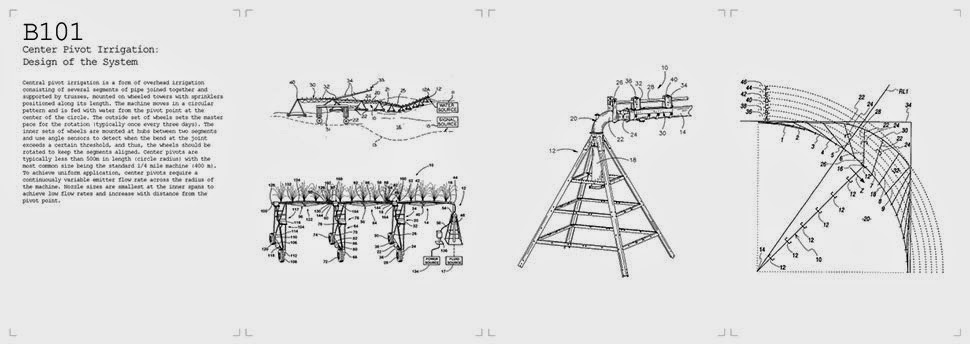

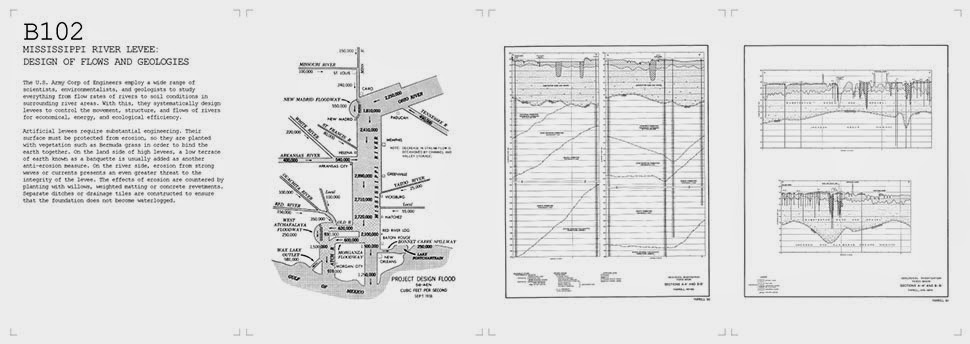

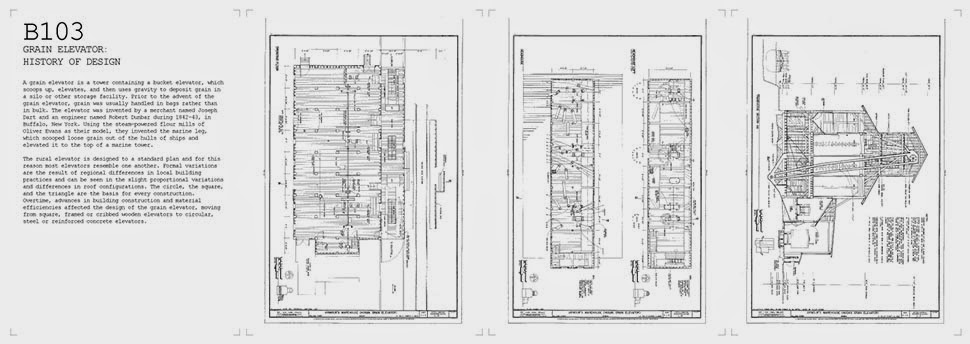

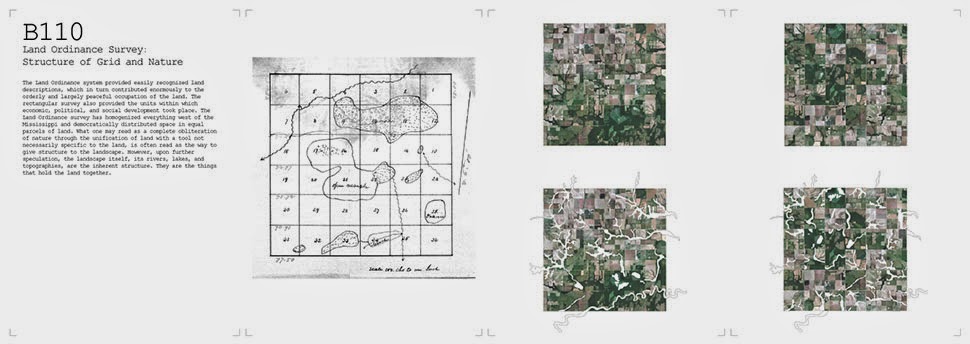

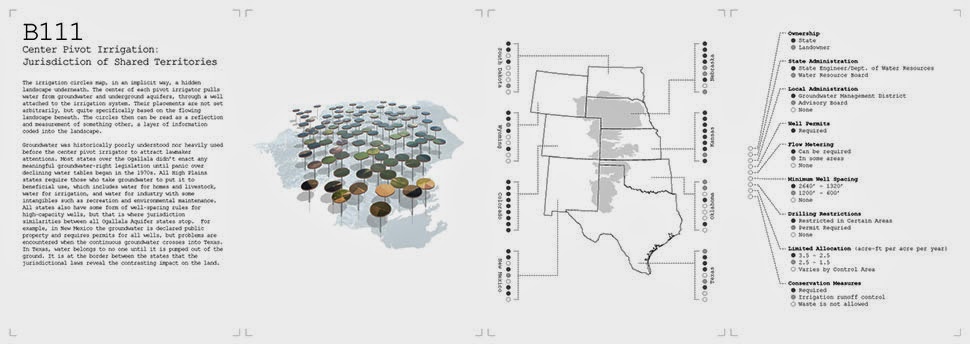

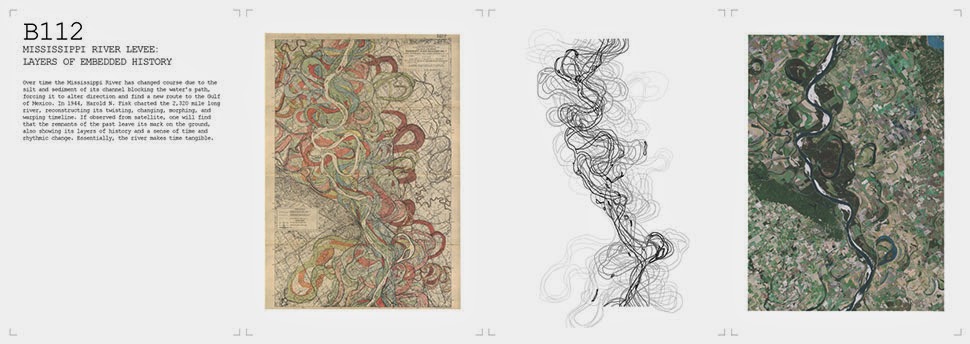

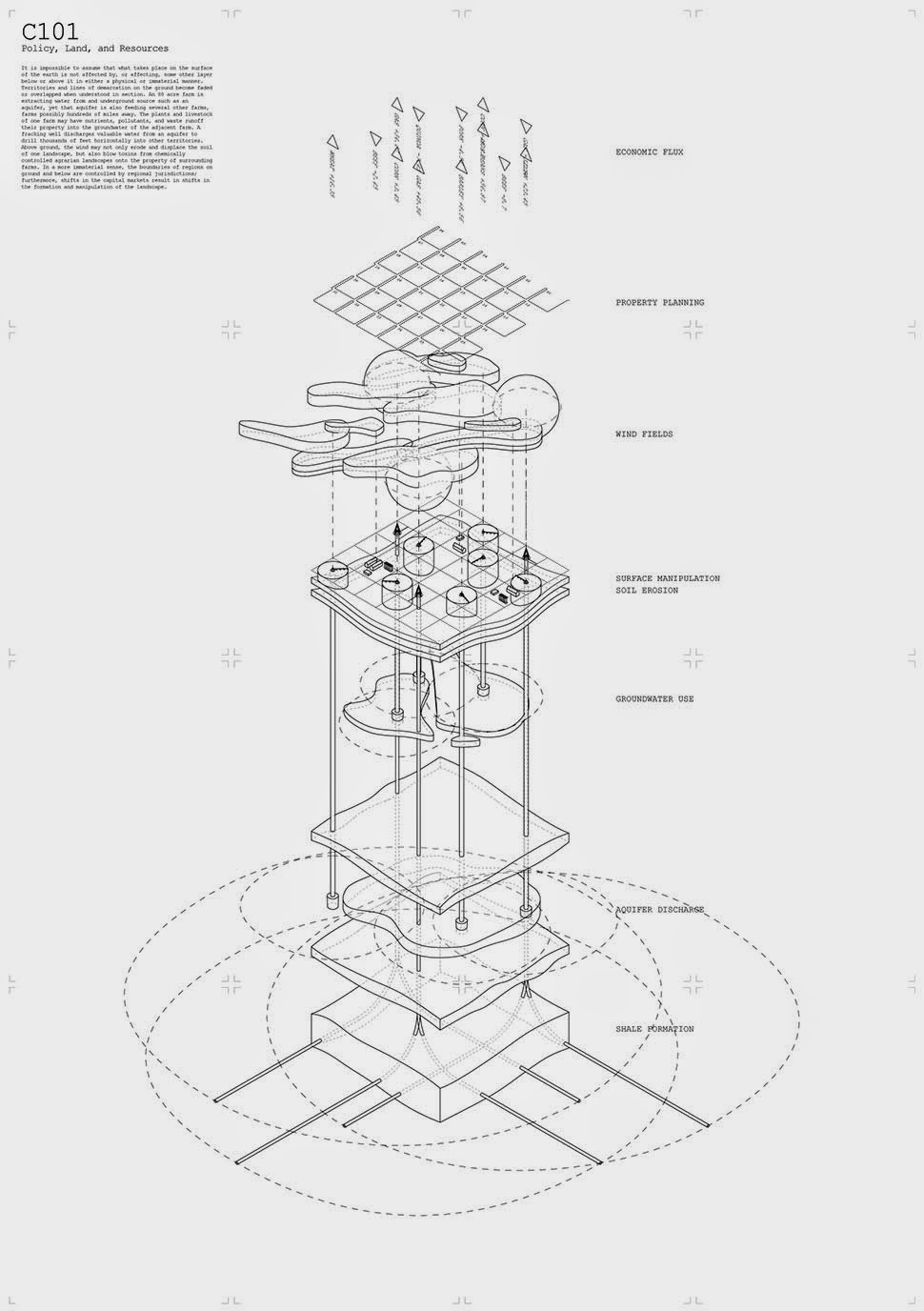

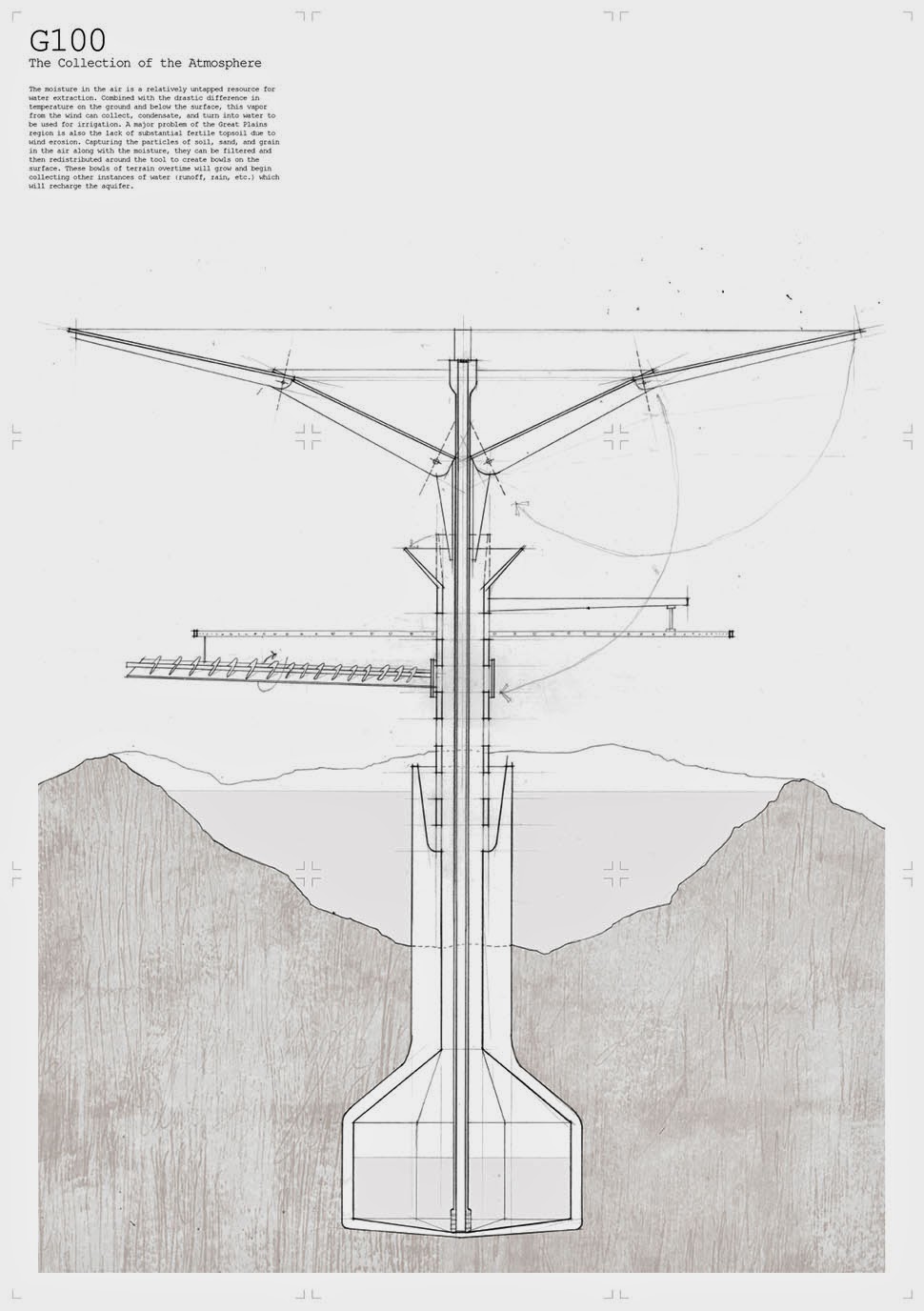

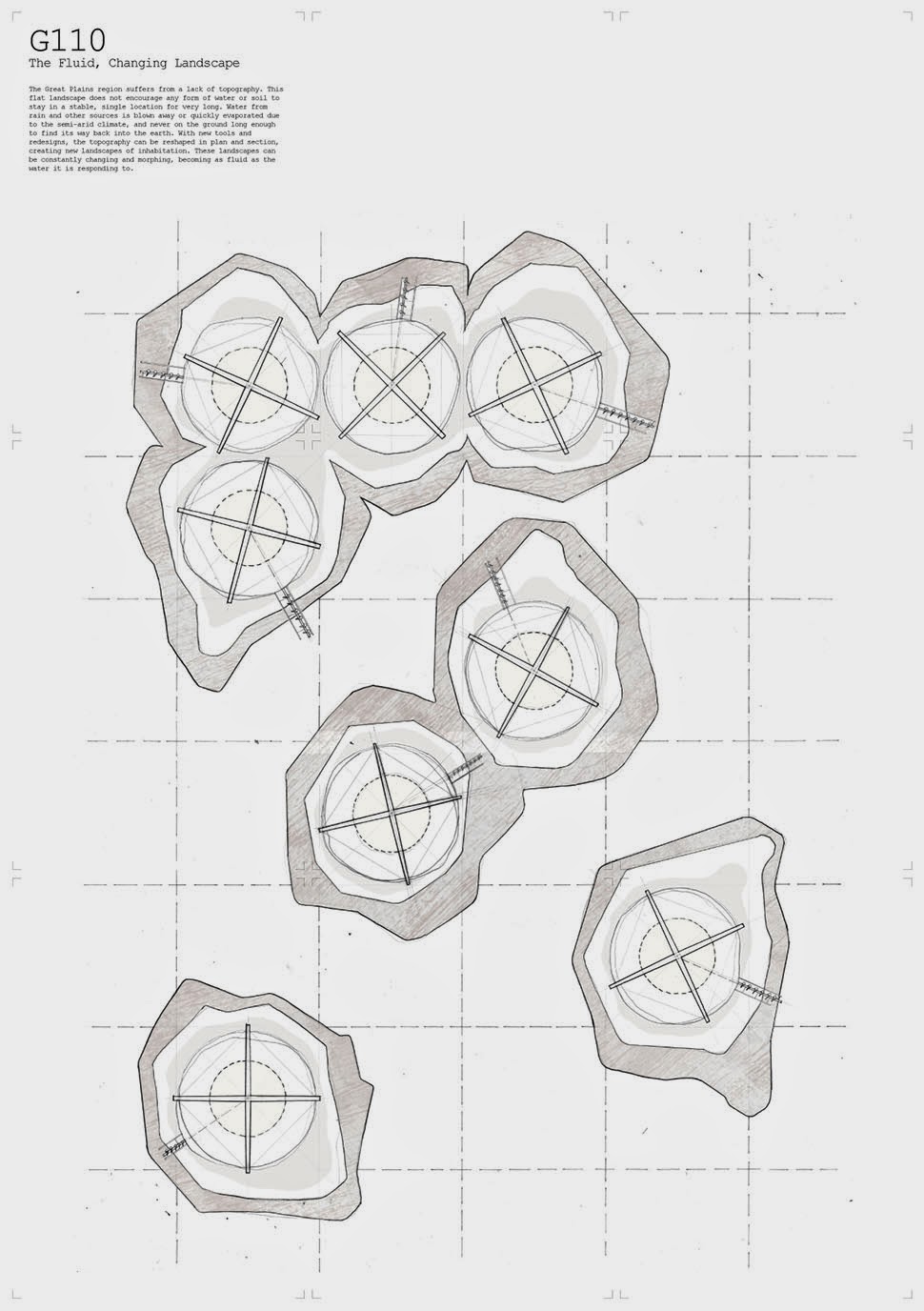

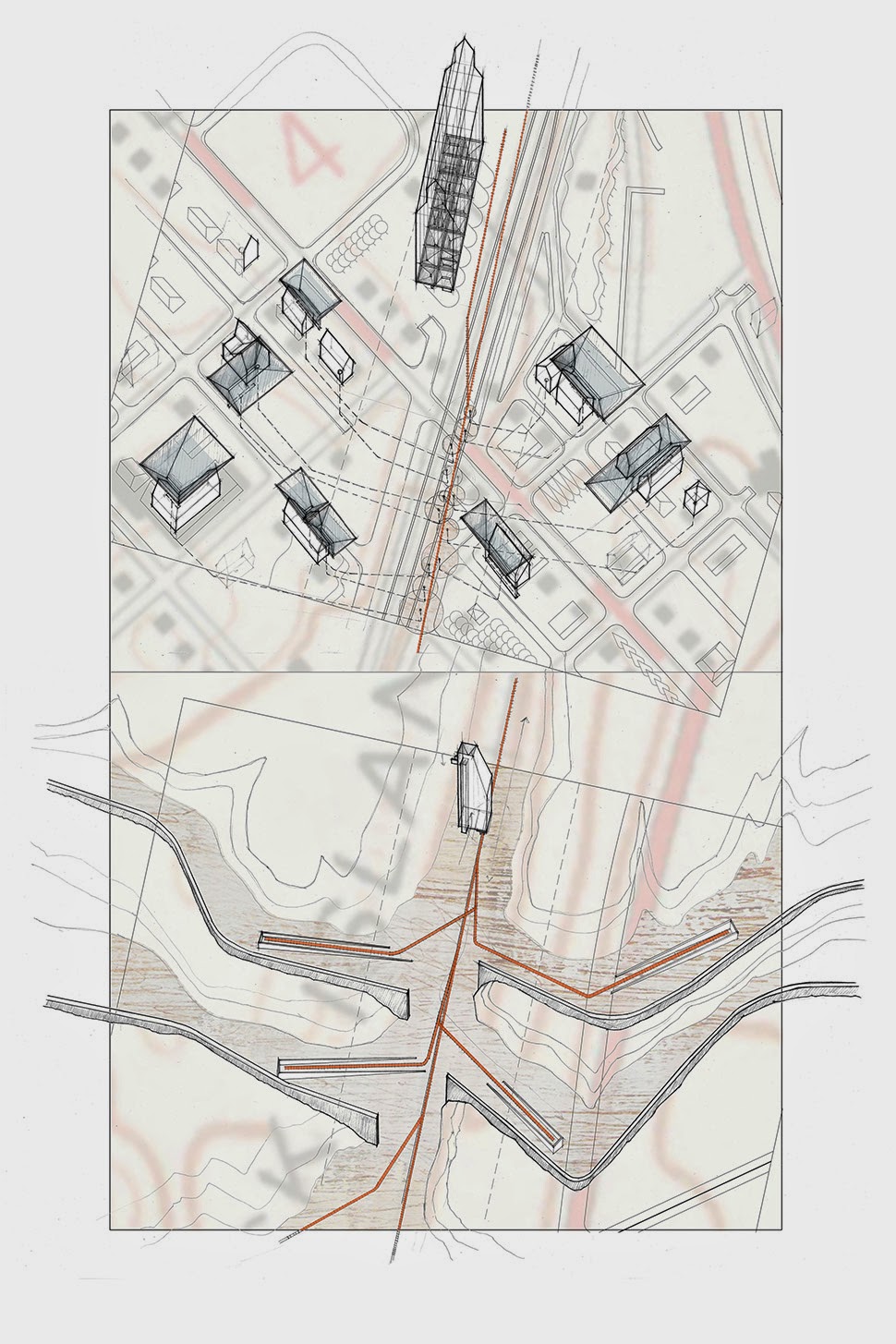

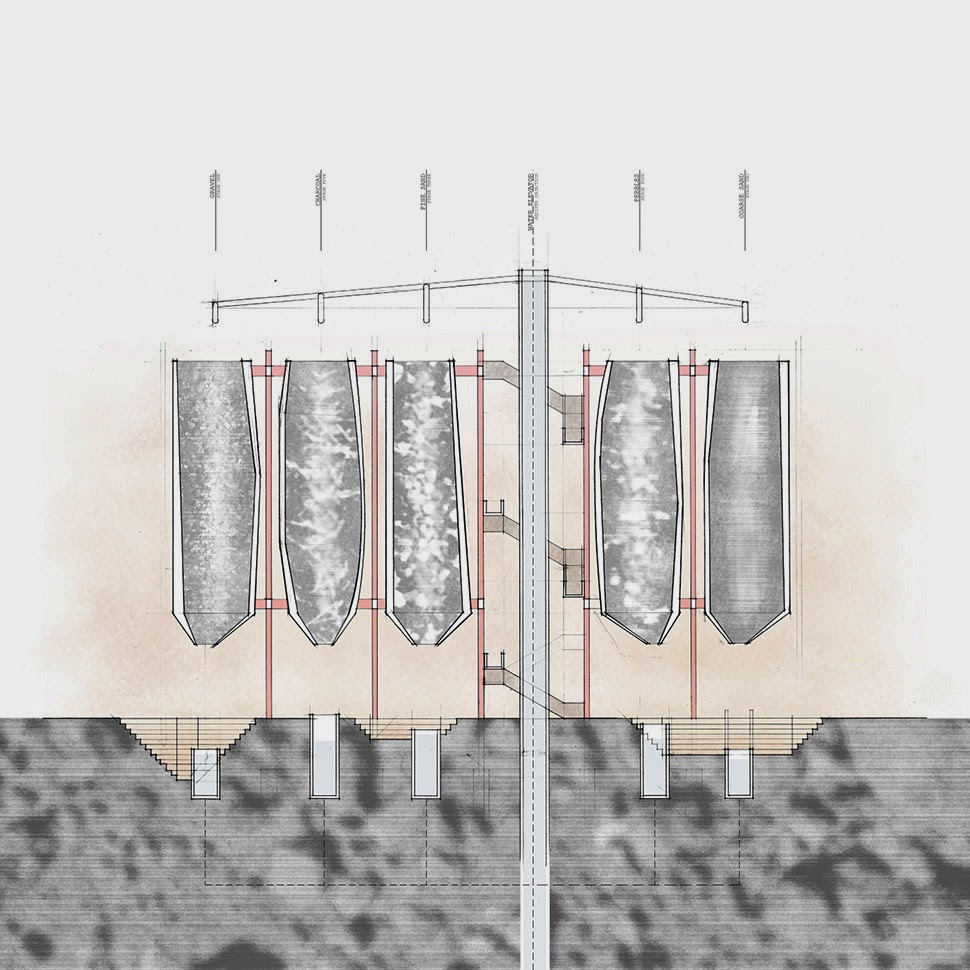

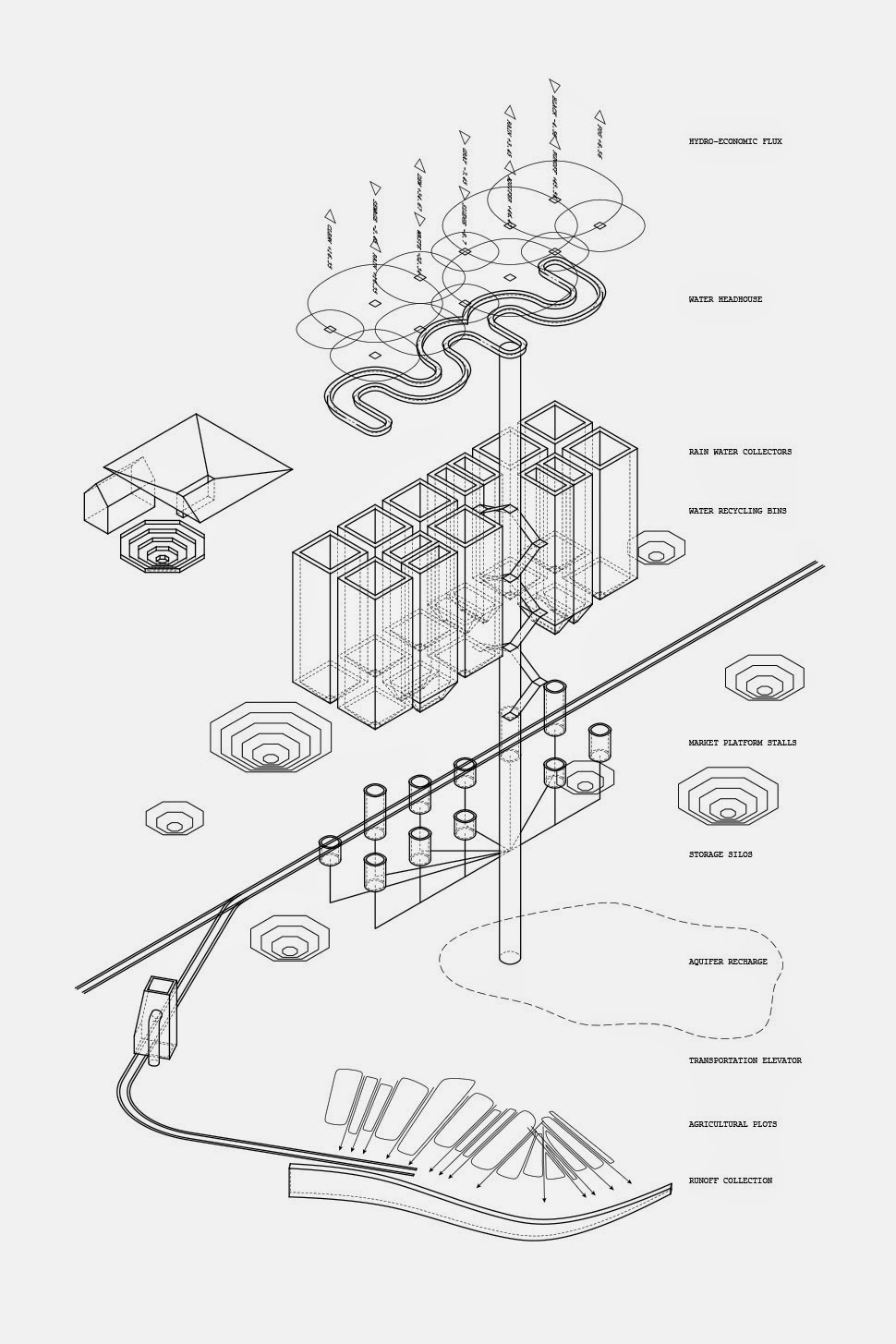

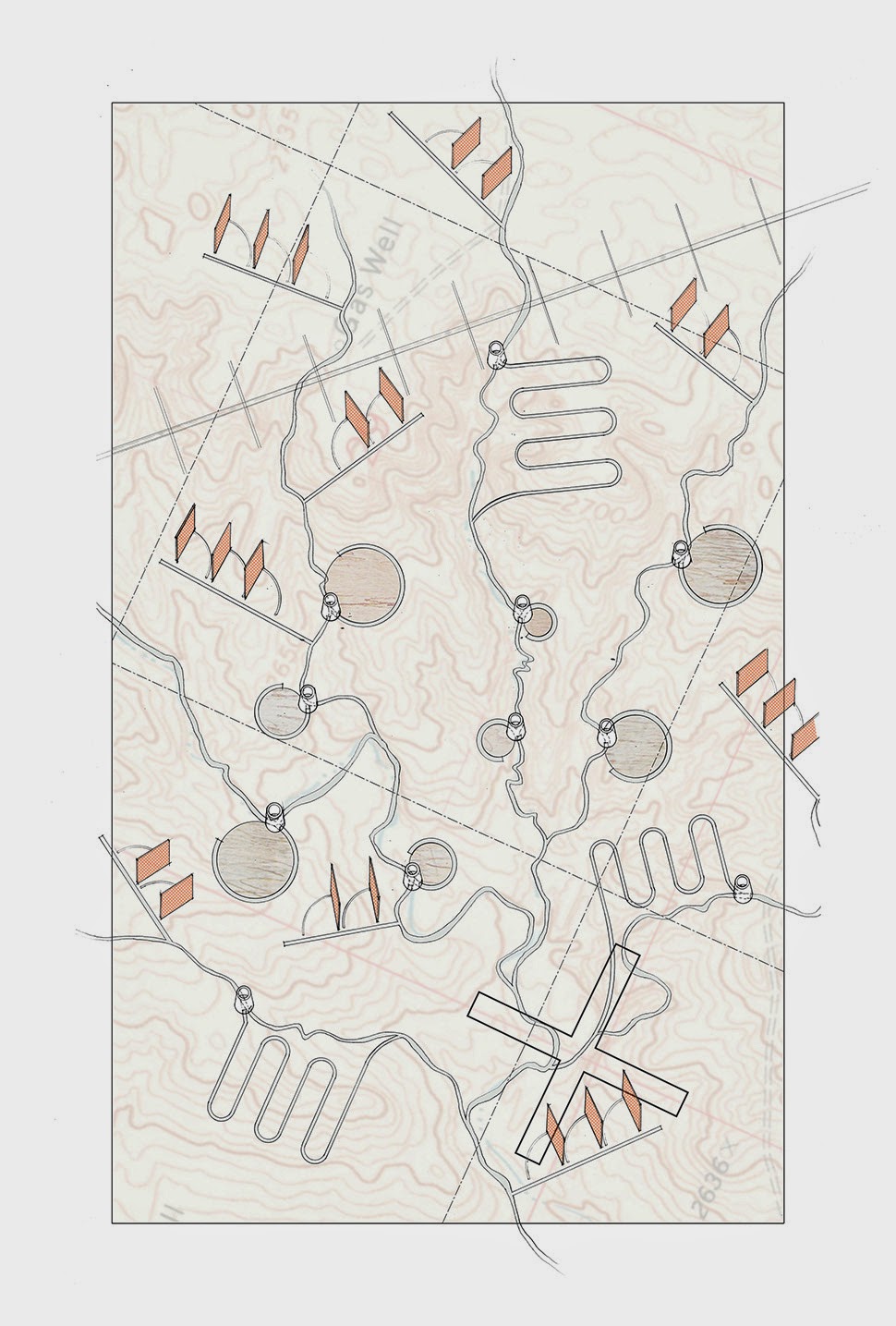

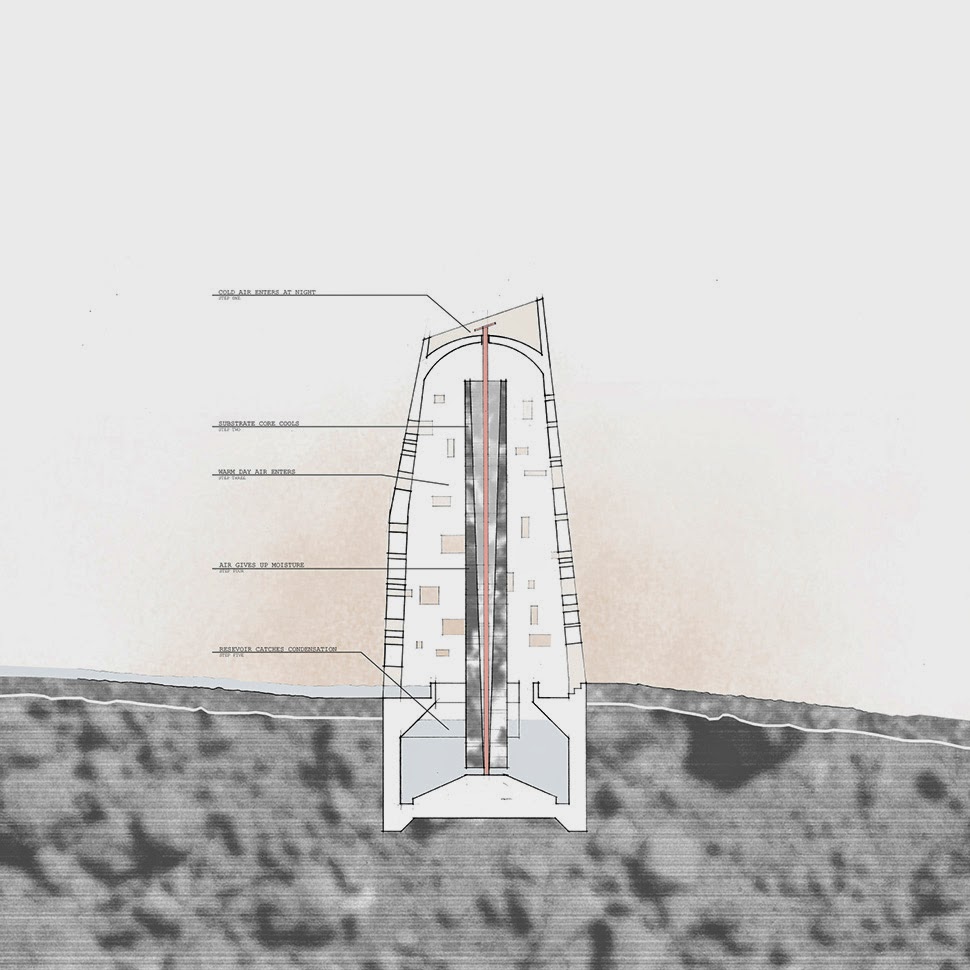

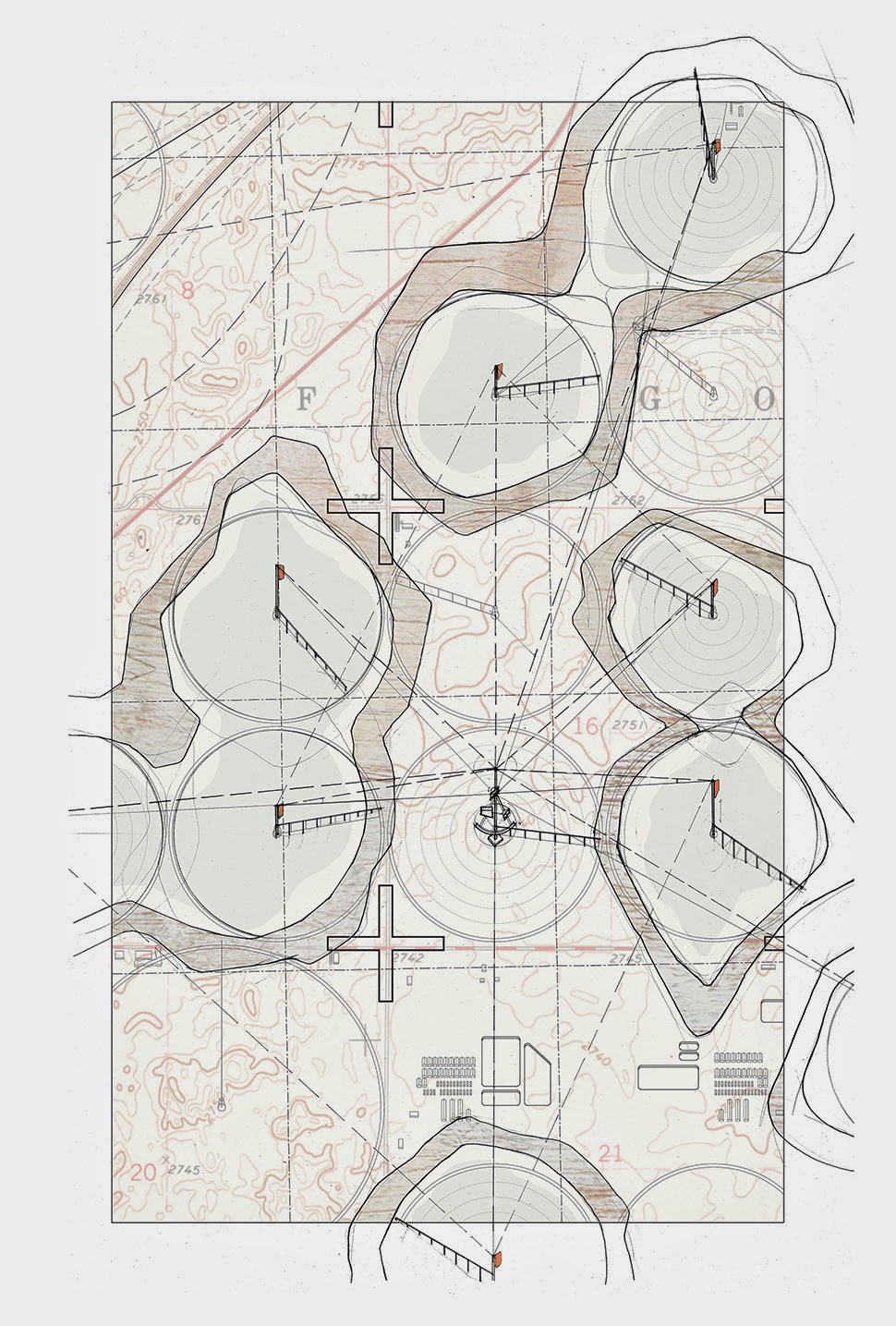

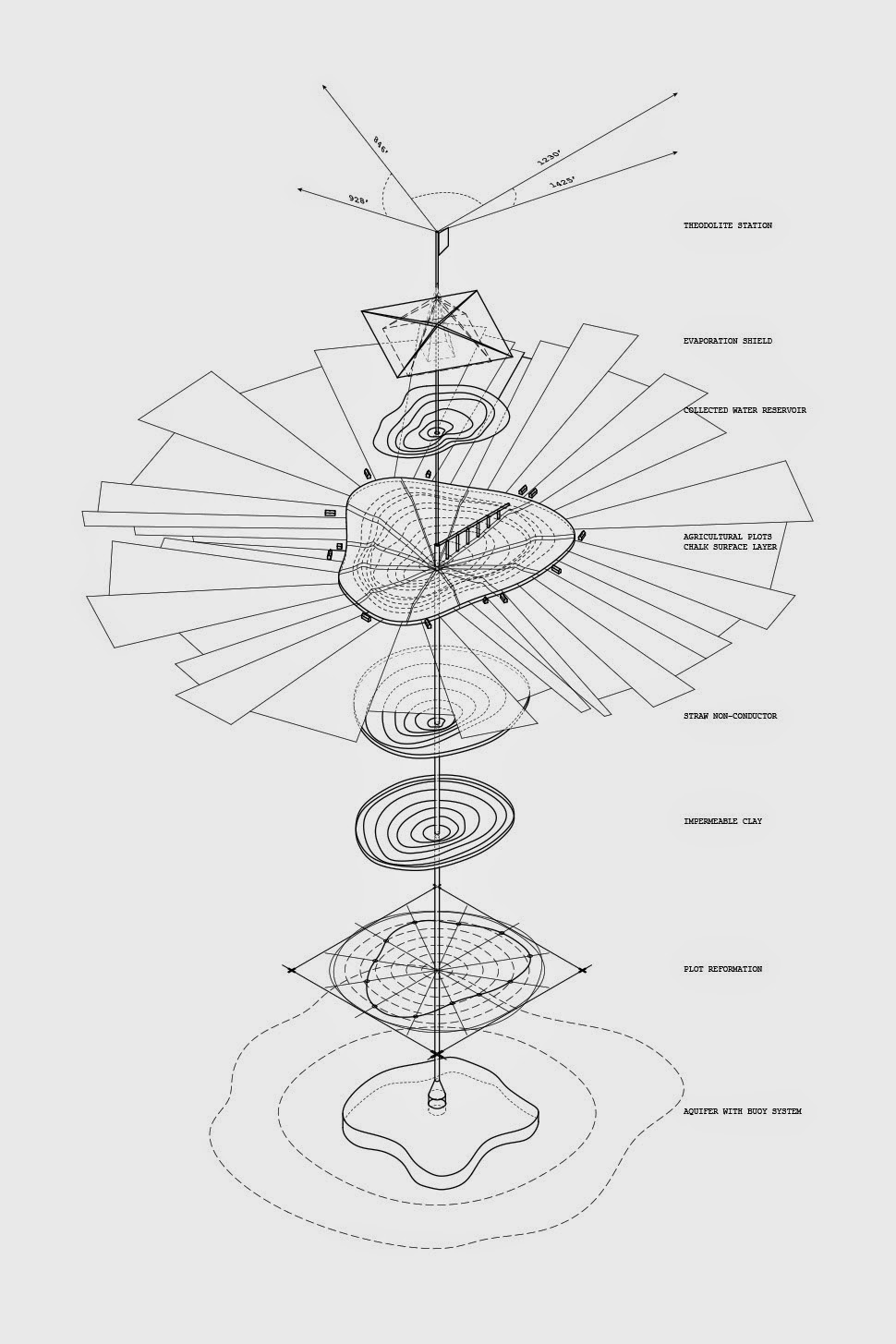

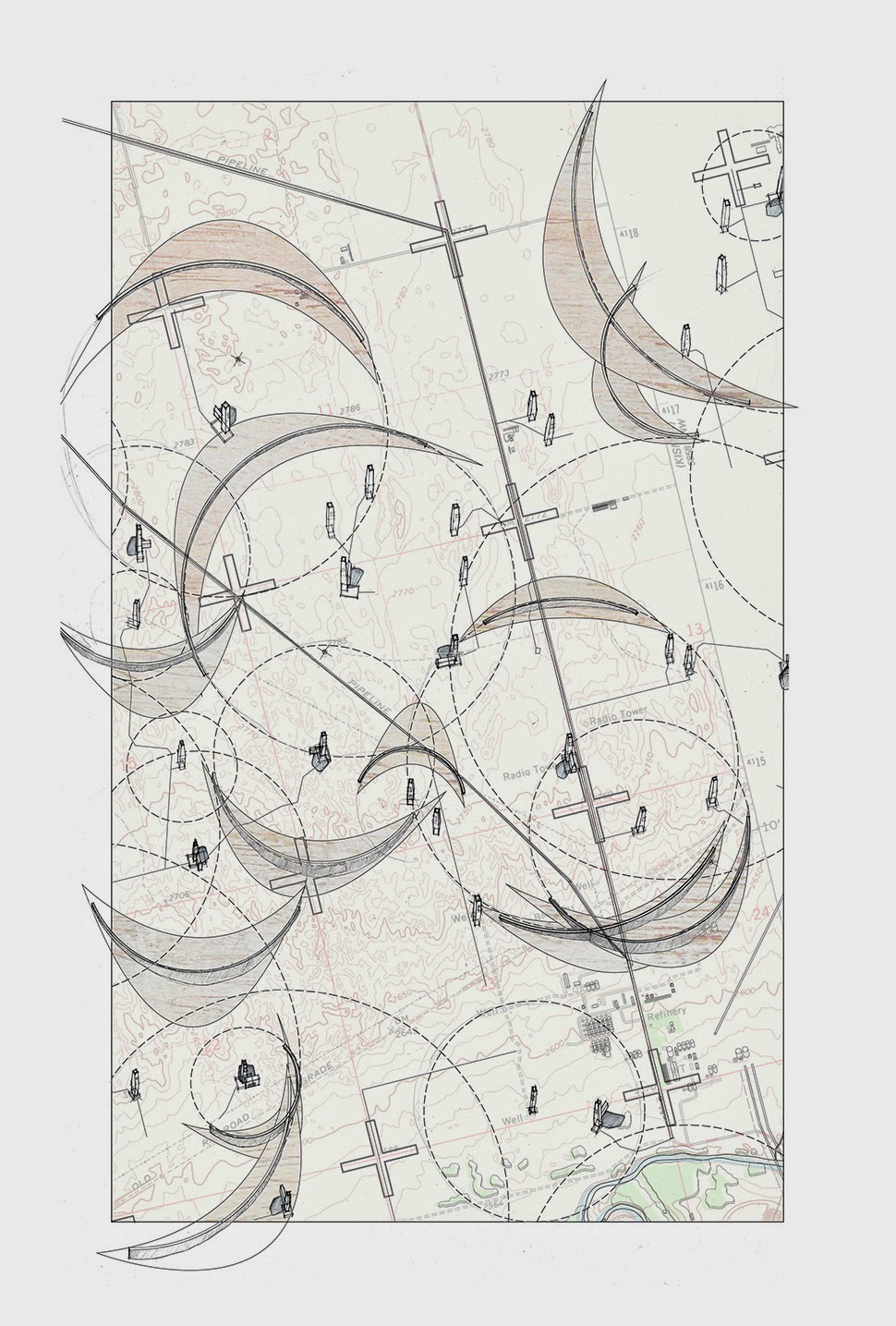

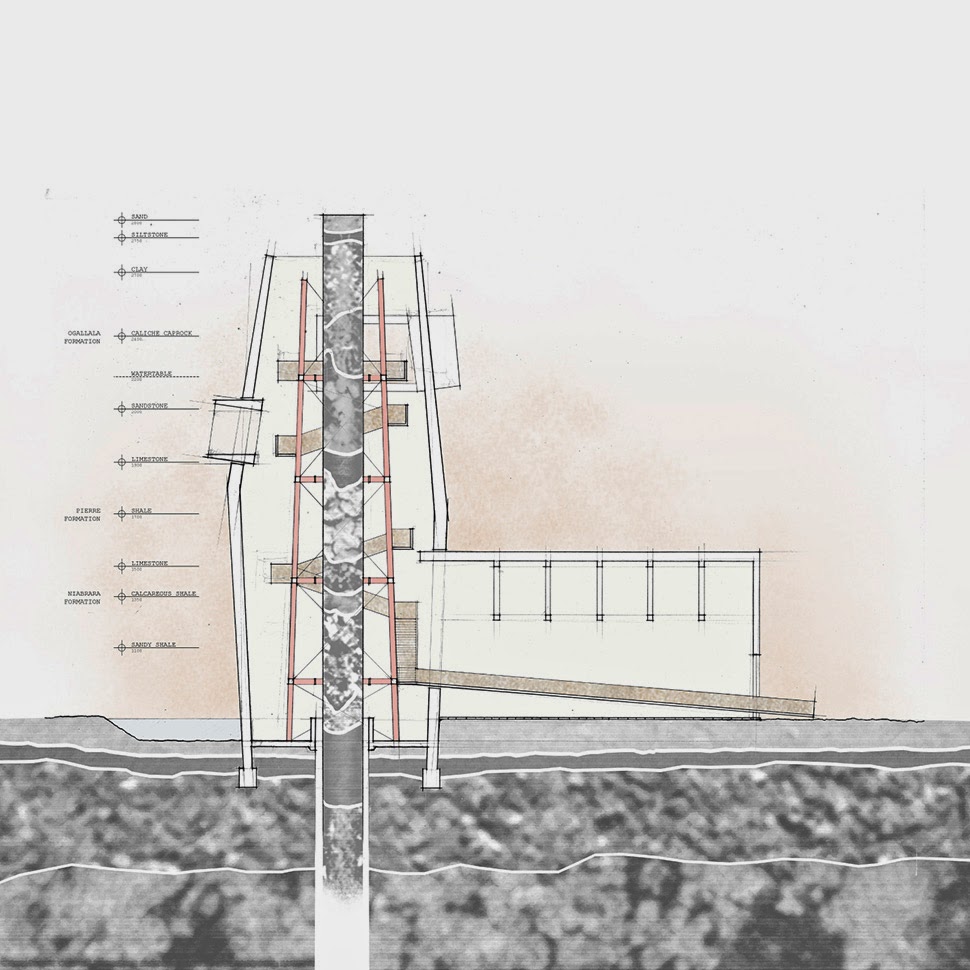

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills]. [Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by