[Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)].

[Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)].

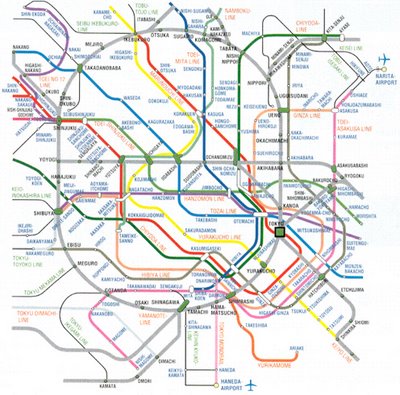

A gigapixel bathymetric map of the Gulf of Mexico’s seabed has been released, and it’s incredible. The newly achieved level of detail is almost hard to believe.

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)].

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)].

The geology of the region is “driven not by plate tectonics but by the movement of subsurface bodies of salt,” Eos reported last week. “Salt deposits, a remnant of an ocean that existed some 200 million years ago, behave in a certain way when overlain by heavy sediments. They compact, deform, squeeze into cracks, and balloon into overlying material.”

This means that the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico “is a terrain continually in flux.”

How the salt got there is the subject of a long but fascinating description at Eos.

It is hypothesized that the salt precipitated out of hypersaline seawater when Africa and South America pulled away from North America during the Triassic and Jurassic, some 200 million years ago. The [Gulf of Mexico] was initially an enclosed, restricted basin into which seawater infiltrated and then evaporated in an arid climate, causing the hypersalinity (similar to what happened in the Great Salt Lake in Utah and the Dead Sea between Israel and Jordan).

Salt filled the basin to depths of thousands of meters until it was opened to the ancestral Atlantic Ocean and consequently regained open marine circulation and normal salinities. As geologic time progressed, river deltas and marine microfossils deposited thousands more meters of sediments into the basin, atop the thick layer of salt.

The salt, subjected to the immense pressure and heat of being buried kilometers deep, deformed like putty over time, oozing upward toward the seafloor. The moving salt fractured and faulted the overlying brittle sediments, in turn creating natural pathways for deep oil and gas to seep upward through the cracks and form reservoirs within shallower geologic layers.

These otherwise invisible landscape features “oozing upward” from beneath the seabed are known as salt domes, and they are not only found at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

The black and white photos you see here are from a salt mine on Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress. The photos date back as far as 1900, and they’re gorgeous.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

This is what it looks like inside those salt domes, you might way, once industrially equipped human beings have carved wormlike topological spaces into the deformed, ballooning salt deposits of the region.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

Obviously, the Gulf of Mexico is not the only salt-rich region of the United States; there is a huge salt mine beneath the city of Detroit, for example, and the nation’s first nuclear waste repository, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, or WIPP—which my wife and I had the surreal pleasure of visiting in person back in 2012—is dug into a huge underground salt deposit near the New Mexico/Texas border.

[Image: Inside WIPP; photo by Nicola Twilley].

[Image: Inside WIPP; photo by Nicola Twilley].

Nonetheless, the Louisiana/Gulf of Mexico salt dome region has lent itself to some particularly provocative landscape myths.

You might recall, for example, the story of Lake Peigneur, an inland body of water that was almost entirely drained from below when a Texaco drilling rig accidentally punctured a salt dome beneath the lake.

This led to the sight of a rapid, Edgar Allan Poe-like maelström of swirling water disappearing into the abyss, pulling no fewer than eleven barges into the terrestrial deep.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

But there is also the story of Bayou Corne, one of my favorite conspiracy theories of all time.

[Images: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Images: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

As the New York Times reported back in 2013, “in the predawn blackness of Aug. 3, 2012, the earth opened up—a voracious maw 325 feet across and hundreds of feet deep, swallowing 100-foot trees, guzzling water from adjacent swamps and belching methane from a thousand feet or more beneath the surface.”

One resident of the area is quoted as saying, “I think I caught a glimpse of hell in it.”

More than a year after it appeared, the Bayou Corne sinkhole is about 25 acres and still growing, almost as big as 20 football fields, lazily biting off chunks of forest and creeping hungrily toward an earthen berm built to contain its oily waters. It has its own Facebook page and its own groupies, conspiracy theorists who insist the pit is somehow linked to the Gulf of Mexico 50 miles south and the earthquake-prone New Madrid fault 450 miles north. It has confounded geologists who have struggled to explain this scar in the earth.

To oversimplify things, the overall theory—that is, the conspiratorial part of all this—is that the entire landscape of the Gulf region is on the verge of subterranean dissolution. The very salt deposits so beautifully mapped by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management are all lined up for eventual flooding.

As this vast underground landscape of salt dissolves, everything from east Texas to west Florida will be sucked down into the abyss.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

It’s unlikely that this will happen, I should say. You can sleep well at night.

In the meantime, the sorts of salt-mining operations depicted here in these photographs have carved their worming, subterranean way into the warped terrains of salt that dynamically ooze their way up to the surface from geological prehistory.

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

[Image: Avery Island, Louisiana, archived by the U.S. Library of Congress].

Be sure to check out the full gigapixel BOEM map, and the helpful write-up over at Eos is worth a read, as well. As for the Bayou Corne conspiracy—I suppose we’ll just have to wait.

(Bathymetric maps spotted via Chris Rowan; salt mine photos originally spotted a very long time ago via Attila Nagy).

[Image: Curtains mistaken for Ryan Gosling; original image supplied by Jomppe Vaarakallio, courtesy PetaPixel; click through to PetaPixel to see the Gosling’d image.]

[Image: Curtains mistaken for Ryan Gosling; original image supplied by Jomppe Vaarakallio, courtesy PetaPixel; click through to PetaPixel to see the Gosling’d image.] [Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Image: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (

[Images: Courtesy U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management ( [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From the

[Image: From the