[Image: Outside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London; all photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Outside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London; all photos by BLDGBLOG].

Before leaving London last week, I learned that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry was offering walk-in tours for the duration of the Olympics, so Nicola Twilley and I headed out to see—and hear—what was on offer.

[Image: Inside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

[Image: Inside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

I’d say, first off, that the tour is well worth it and that everyone on hand to help us along on the self-guided tour seemed genuinely pleased to have members of the public coming through. Second of all, if you have any interest at all in the relationship between cities and acoustics—say, the influence of bells on neighborhood identity or the subtle differences in city soundscapes based on different profiles moulded into church bells—then it’s a fabulous way to spend the afternoon.

We were there for nearly two hours, but I still felt like we were rushing.

[Image: Bell-making tools at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

[Image: Bell-making tools at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

In any case, the Foundry bills itself, and is apparently recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records, as the oldest manufacturing company in Britain. They made Big Ben; they forged the first Liberty Bell; they created, albeit off-site, the absolutely massive 23-ton 2012 Olympic Bell; and, among thousands of other, less well-known projects, they even made the famed Bow bells whose ringing defines London’s Cockney stomping ground.

[Image: The ingredients of loam].

[Image: The ingredients of loam].

The self-guided tour took us from buckets of loam, used to shape the earthen moulds into which “bell metal” (an alloy of copper and tin) is later poured during casting, all the way to the mind-blowing final sight and sound of the bell-tuning station.

Here are some quick photos, then I’ll come back to the tuning process.

[Images: Interior of the Foundry, plus some of the casting/pouring equipment. In the bottom two images, the frames visible on the back wall were used to cast, from left to right, Big Ben; the original Liberty Bell; the Bow bells; the enormous 2012 Olympic Bell; and another bell, on the far right, that I unfortunately don’t remember].

[Images: Interior of the Foundry, plus some of the casting/pouring equipment. In the bottom two images, the frames visible on the back wall were used to cast, from left to right, Big Ben; the original Liberty Bell; the Bow bells; the enormous 2012 Olympic Bell; and another bell, on the far right, that I unfortunately don’t remember].

The next sequence shows the casting of hand bells. We were basically in the right place at the right time to see this process, as the gentleman pictured—whose denim vest had written on it in black marker, “I’m not mad, I’m mental, HA! HA! HA!”—pulled apart the suitcase-like casting frame seen in these photos to reveal gorgeously bright golden bells sitting silently inside.

Using powder, almost like something you’d use to sugar a cake, and an air-hose, he removed the bells from their loamy matrix and got the frame ready for another use.

[Image: The bells are revealed and powdered].

[Image: The bells are revealed and powdered].

The whole thing was a kind of infernal combination of kilns and liquid metal, soundtracked by the sharp metallic ring of bells resonating in the background.

As the origin site for urban instruments—acoustic ornaments worn by the city’s architecture to supply a clockwork soundtrack that bangs and echoes over rooftops—the Foundry had the strange feel of being both an antique crafts workshop of endangered expertise (kept afloat almost entirely by commissions from churches) and a place of stunning, almost futuristic, design foresight.

In other words, the acoustic design of the city—something that isn’t even on the agenda of architecture schools today, considered, I suppose, too hard to model with Rhino—was taking place right there, and had been for centuries, in the form of vast ovens and casting frames out of which emerge the instruments—shining bells—that so resonantly redefine the experience of the modern metropolis.

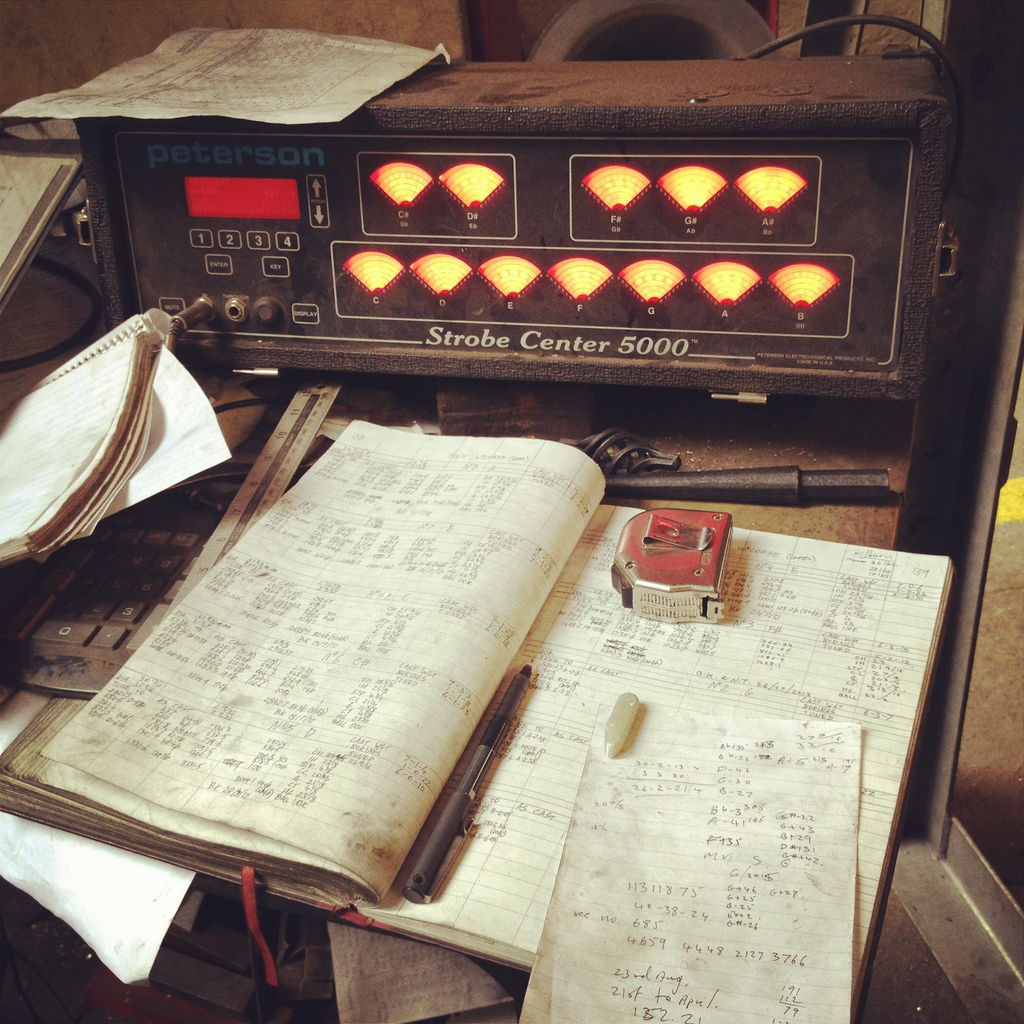

So that brings us to the final stage of the Foundry tour, which was the tuning station.

[Images: Tuning a bell; note the shining flecks of metal on the floor, which have been scraped out of the bell in order to tune it. “Tuning” is thus a kind of mass reduction, or reductive sculpting].

[Images: Tuning a bell; note the shining flecks of metal on the floor, which have been scraped out of the bell in order to tune it. “Tuning” is thus a kind of mass reduction, or reductive sculpting].

Assuming I remembered this correctly, modern bells are tuned by having tiny bits of metal—mere flecks at a time—scraped or cut away from the inside. This produces an incredible texture of bright, polished grooves incised directly, even violently, into the metal; the visual effect is absolutely magical.

[Image: The grooved interior of a recently tuned bell; in the bottom image, note the word “tenor” written on the bell’s inner rim].

[Image: The grooved interior of a recently tuned bell; in the bottom image, note the word “tenor” written on the bell’s inner rim].

Even better, while these massive bells are rotating anti-clockwise on their turning plates, having their insides scraped away, they are actually ringing!

Deep below the abrasive droning roar of the bell turning you can make out the resonant tone of the bell itself. The effect was like listening to tuned rocks falling endlessly in a tumbler, polished into acoustically more beautiful versions of themselves. This process alone could make a new instrument: a full orchestra of bell-tuning stations, as if mining shaped metals for their sounds.

Finally, then, the tuning process is controlled by one of three ways, often used in combination. One uses software; you bang the bell with a mallet and the software tells you if it’s resonating at the right frequencies. The second method uses an oscilloscope, which looks like something straight out of a 1980s submarine-warfare movie.

[Image: As if looking for ghosts inside the bell, the oscilloscope spins and glows].

[Image: As if looking for ghosts inside the bell, the oscilloscope spins and glows].

And the third is much more analogue, relying entirely on the tuner’s own sense of pitch and the use of tuning forks.

[Image: Tuning forks at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

[Image: Tuning forks at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

At the risk of going on too long about this, there really was something almost indescribably beautiful about the tuning process: watching, and listening to, otherwise featureless metal surfaces be sculpted and inscribed from inside by an anti-clockwise machine as the weird circular howl of the bell grew gradually more distinct, more precisely pitched with every scraping away of unpolished metal.

Being, as you’ll know by now, prone to clichés, I can’t help but think of William Blake’s “Satanic Mills” of the Industrial Revolution every time I enter an industrial facility these days, and a vision of some titanic factory somewhere in the pollution of a future era, spinning raw metal into bells, golden and shrieking things droning as if enspirited or possessed, is almost too fantastical to contemplate.

Anyway, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry is open for walk-in tours, for £10 per adult, until the end of the 2012 Olympics, after which the tours go back to advance reservations only (and the ticket price goes up to £12). Enjoy!

[Image: Field Studies 2012 runs 10-13 September 2012 in London].

[Image: Field Studies 2012 runs 10-13 September 2012 in London].

[Image: Outside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London; all photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Outside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London; all photos by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: Inside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

[Image: Inside the Whitechapel Bell Foundry]. [Image: Bell-making tools at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry].

[Image: Bell-making tools at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry]. [Image: The ingredients of loam].

[Image: The ingredients of loam].

[Images: Interior of the Foundry, plus some of the casting/pouring equipment. In the bottom two images, the frames visible on the back wall were used to cast, from left to right, Big Ben; the original Liberty Bell; the Bow bells; the enormous 2012 Olympic Bell; and another bell, on the far right, that I unfortunately don’t remember].

[Images: Interior of the Foundry, plus some of the casting/pouring equipment. In the bottom two images, the frames visible on the back wall were used to cast, from left to right, Big Ben; the original Liberty Bell; the Bow bells; the enormous 2012 Olympic Bell; and another bell, on the far right, that I unfortunately don’t remember].

[Image: The bells are revealed and powdered].

[Image: The bells are revealed and powdered].

[Images: Tuning a bell; note the shining flecks of metal on the floor, which have been scraped out of the bell in order to tune it. “Tuning” is thus a kind of mass reduction, or reductive sculpting].

[Images: Tuning a bell; note the shining flecks of metal on the floor, which have been scraped out of the bell in order to tune it. “Tuning” is thus a kind of mass reduction, or reductive sculpting].

[Image: The grooved interior of a recently tuned bell; in the bottom image, note the word “tenor” written on the bell’s inner rim].

[Image: The grooved interior of a recently tuned bell; in the bottom image, note the word “tenor” written on the bell’s inner rim]. [Image: As if looking for ghosts inside the bell, the oscilloscope spins and glows].

[Image: As if looking for ghosts inside the bell, the oscilloscope spins and glows]. [Image: Tuning forks at the

[Image: Tuning forks at the

Two

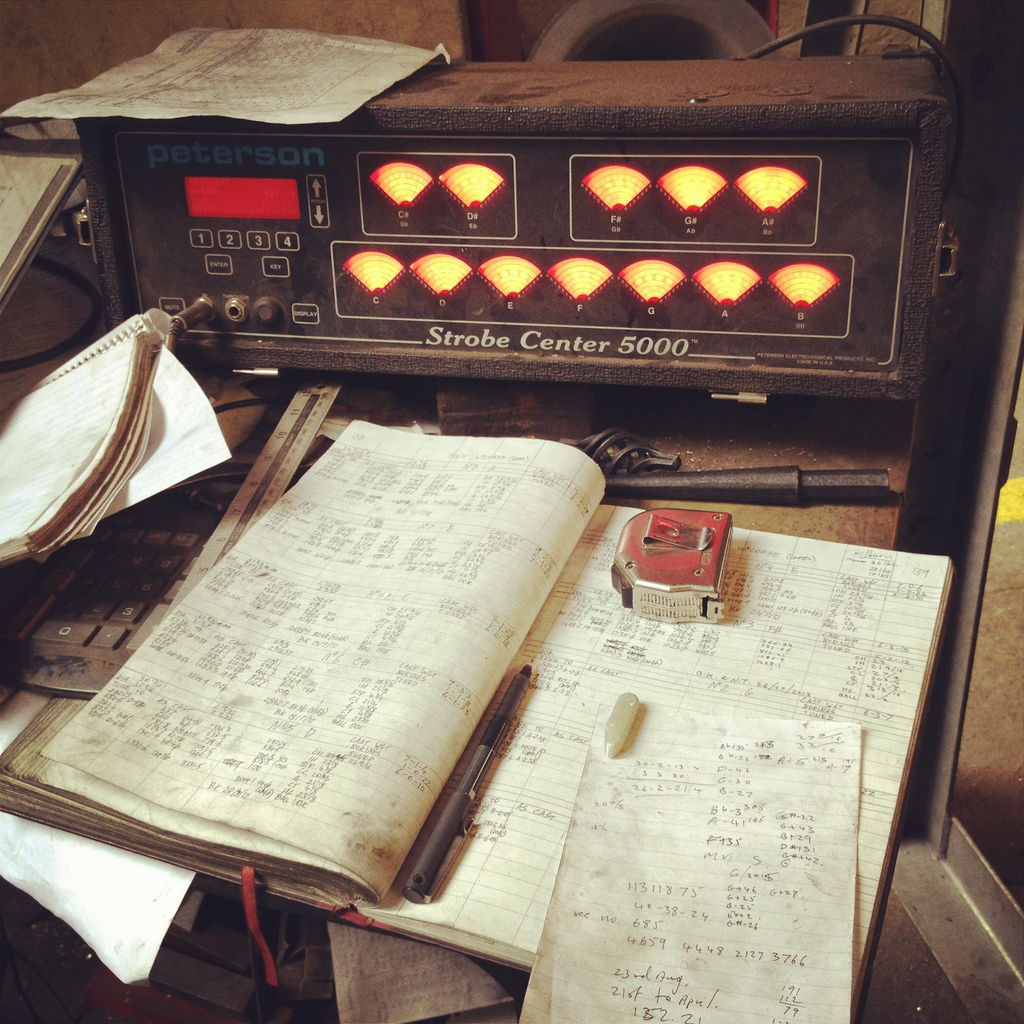

Two  Back here in New York, meanwhile, on Saturday, August 11th, Matthew Coolidge, director of the

Back here in New York, meanwhile, on Saturday, August 11th, Matthew Coolidge, director of the

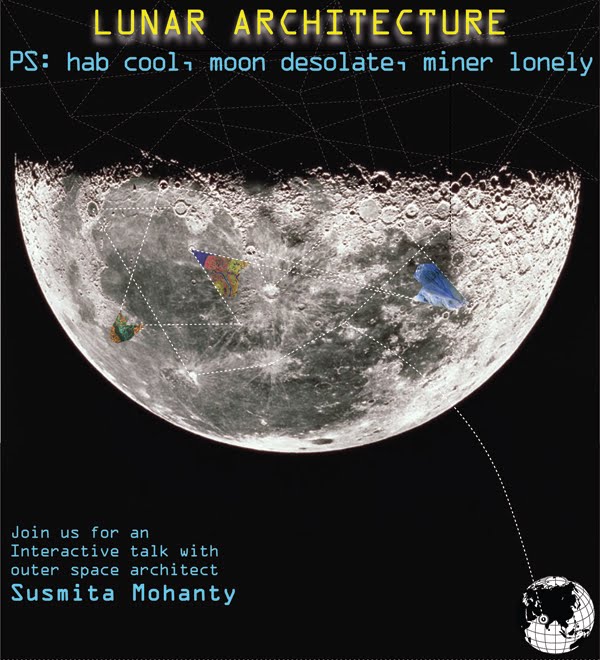

[Image: Piranesi’s Rome].

[Image: Piranesi’s Rome].

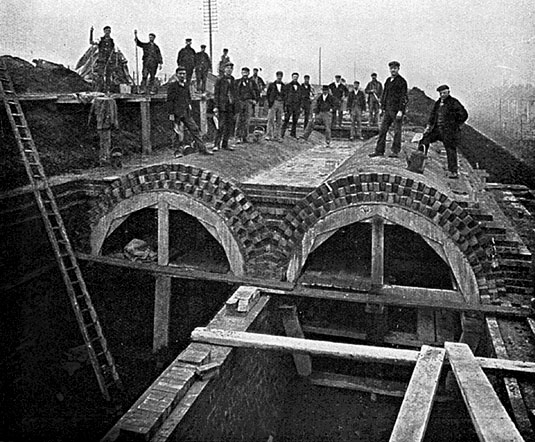

[Image: London’s sewers under construction; via the fascinating

[Image: London’s sewers under construction; via the fascinating  [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: A “flusher,” courtesy of

[Image: A “flusher,” courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of

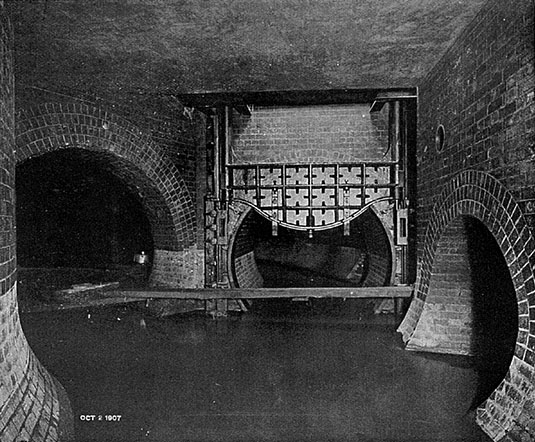

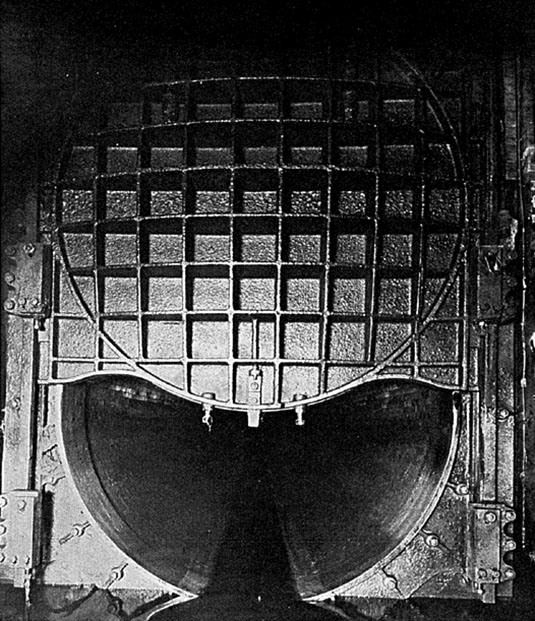

[Image: Courtesy of  [Image: Great iron doors beneath the city; courtesy of

[Image: Great iron doors beneath the city; courtesy of

[Image: Combustible City by

[Image: Combustible City by

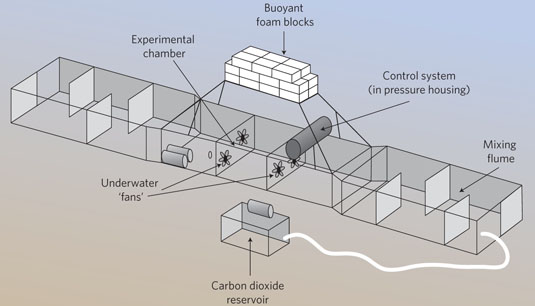

[Image: A diagram of Peter Brewer’s “underwater aquarium,” via

[Image: A diagram of Peter Brewer’s “underwater aquarium,” via  [The “Aspen FACE,” or

[The “Aspen FACE,” or

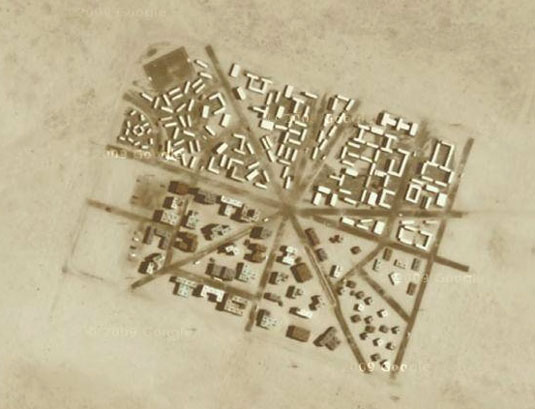

[Image: Yodaville, via

[Image: Yodaville, via  [Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the

[Image: Swiss mountain pass, via

[Image: Swiss mountain pass, via  [Image: Swiss bridge, photographed by

[Image: Swiss bridge, photographed by  [Image: Switzerland’s Gotthard Tunnel, via

[Image: Switzerland’s Gotthard Tunnel, via

[Image: Around Mono Lake, photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Around Mono Lake, photo by BLDGBLOG].