In Richard Mabey’s excellent history—and “defense”—of weeds, previously mentioned on BLDGBLOG back in December, he tells the story of Oxford ragwort, a species native to the volcanic slopes of Sicily’s Mount Etna. Exactly how it arrived in Oxford is unknown, Mabey explains, but it was as likely as not brought back deliberately as part of an 18th-century scientific expedition.

[Image: Cropped photo of Oxford ragwort from the UK National Education Network].

[Image: Cropped photo of Oxford ragwort from the UK National Education Network].

But once it took root in Oxford, it began to spread—and Mabey tells the tale of its territorial expansion in forensic close-up. You can literally track this on Google Maps. Quoting him at length:

Within a few years the ragwort had escaped from the garden (which is sited opposite Magdalen College) and begun its westward progress along Oxford’s ancient walls. Its downy seeds seemed to find an analogue of the volcanic rocks of its original home in the cracked stonework. It leap-frogged from Merton College to Corpus Christi and the august parapets of Christ Church, then wound its way through the narrow alleys of St. Aldate’s. It got to Folly Bridge over the Isis, and then to the site of the old workhouse in Jericho, where, as if recognizing that this was a place of poverty, threw up a strange diminutive variant, a type with flower heads half the normal size (var. parviflorus). Sometime in the 1830s it arrived at Oxford Railway Station, the portal to a nationwide, interlinked network of Etna-like stone chips and clinker. Once it was on the railway companies’ permanent ways there was no holding it. The seeds were wafted on by the slipstream of the trains, and occasionally traveled in the carriages. The botanist George Claridge Druce described a trip he took with some on a summer’s afternoon in the 1920s. [Ragwort seeds] floated in through his carriage window at Oxford and “remained suspended in the air till they found an exit at Tilehurst,” twenty miles down the line.

So ragwort came to be everywhere, spreading across “analogous” landscapes that chemically and texturally mimicked the plant’s home ground, establishing itself as an all but ubiquitous plant—an itinerant super-weed riding the nation’s trains and piggybacking stone wall to stone wall—across the United Kingdom.

This step-by-step expansion of a life form’s zone of habitation came to mind when reading the bizarre story of a runaway fungus in Kentucky. “The sooty-looking black gunk has been here for as long as anyone can remember,” the New York Times reported back in August 2012, “creeping on the outside of homes, spreading over porch furniture, blanketing car roofs, mysterious and ever-present.” People in town thought it must be the result of pollution, or perhaps just the town being reclaimed by whatever original moldy life had once inhabited those valleys.

But no: “[I]t turns out the most likely culprit is Kentucky’s signature product, its liquid pride: whiskey, as in bourbon whiskey, distilled and bottled across the city and nearby countryside.” The mold—called Baudoinia—”belongs to a class of fungi that is almost prehistorically tenacious” (and, for good measure, Wired adds that it is “a fungus that’s millions of years old, older than Homo sapiens“).

And it is a dark and spreading presence on the buildings, streets, cars, and even road signs near distilleries, “indiscriminately colonizing exposed surfaces ranging from vegetation to built structures, sign posts and fences (including those made from glass and stainless steel),” the U.S. Department of Energy warns, describing this ancient and sooty form of life.

[Image: Baudoinia growing on a fire hydrant; photo by Ben Sklar, courtesy of the New York Times].

[Image: Baudoinia growing on a fire hydrant; photo by Ben Sklar, courtesy of the New York Times].

Indeed, it’s gotten so bad that towns along the historic Kentucky Bourbon Trail are bringing suit against the distilleries, the New York Times continues: “The dark residue is visible throughout neighborhoods on days when the air carries a slight yeasty smell from nearby whiskey warehouses and on days when it does not, in heat and in damp. It is difficult to get rid of, the lawsuit alleges, returning after repeated commercial cleanings.”

A similar suit in Scotland is now in the works, where “the fungus is so rampant that it almost seems like part of the architecture.” Here, I’m reminded of novelist Jeff VanderMeer‘s idea of domesticated species of lichen being used as living architectural ornament—that, in his words, “much of the ‘gold’ covering the buildings was actually a living organism similar to lichen that [had been] trained to create decorative patterns.”

[Image: Buildings covered in black, growing spotches of Baudoinia; photographer unknown, via Discover].

[Image: Buildings covered in black, growing spotches of Baudoinia; photographer unknown, via Discover].

In any case, this prehistoric “weed,” if you will—a mold not from the slopes of Mount Etna but escaped from barrels of whiskey—offers us an interesting variation on Richard Mabey’s forensic tale of rooted but footloose infestation.

At the center of each story, we find an organism spatially and chemically dependent on the built environment of humans for its success, a species ready and perfectly able to “invade niches which resemble its original habitat,” in Mabey’s words. Living stowaways, they make themselves at home on walls, porches, car hoods, trees, even, in the case of Baudoinia, stainless steel, quietly thriving on whatever systems of objects they might find, eventually merging with and becoming part of the everyday landscape.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image from

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image from

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of lift bags being used in underwater archaeology; via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of lift bags being used in underwater archaeology; via

This autumn—October 12-19, 2013—

This autumn—October 12-19, 2013—

[Image: The World Trade Center towers, photographer unknown].

[Image: The World Trade Center towers, photographer unknown].

[Image: Barbed wire, via

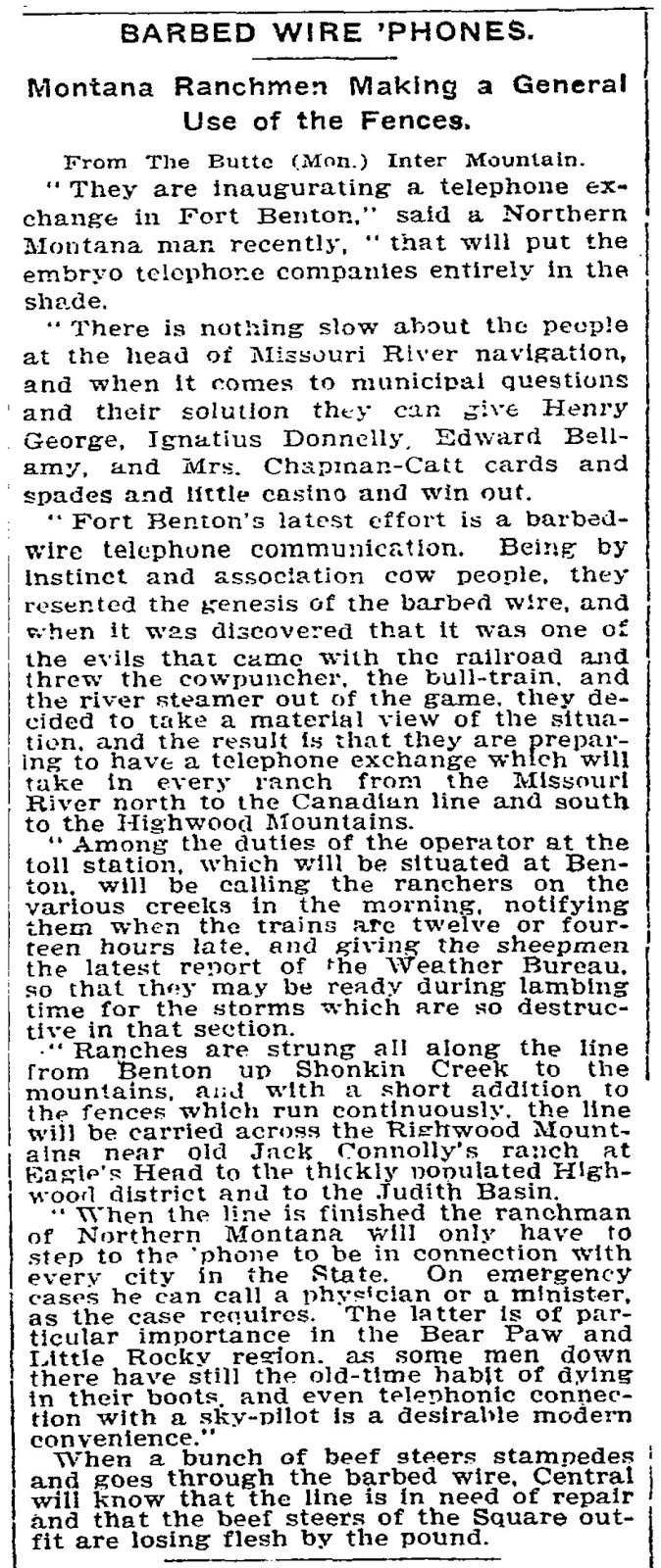

[Image: Barbed wire, via  [Image: From a June 1902 issue of

[Image: From a June 1902 issue of

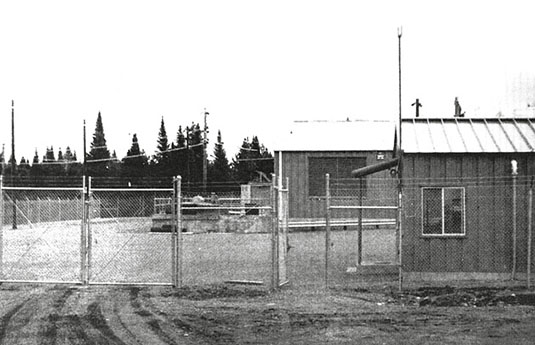

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via  [Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

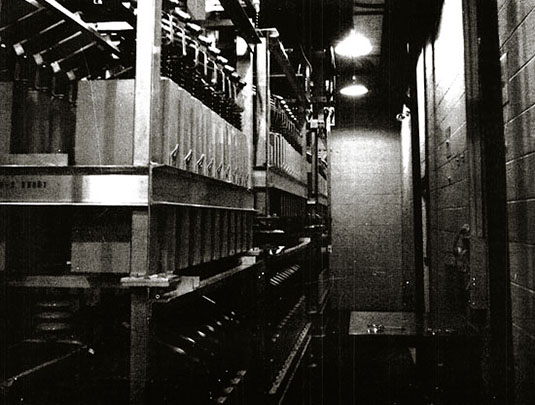

[Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)]. [Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna].

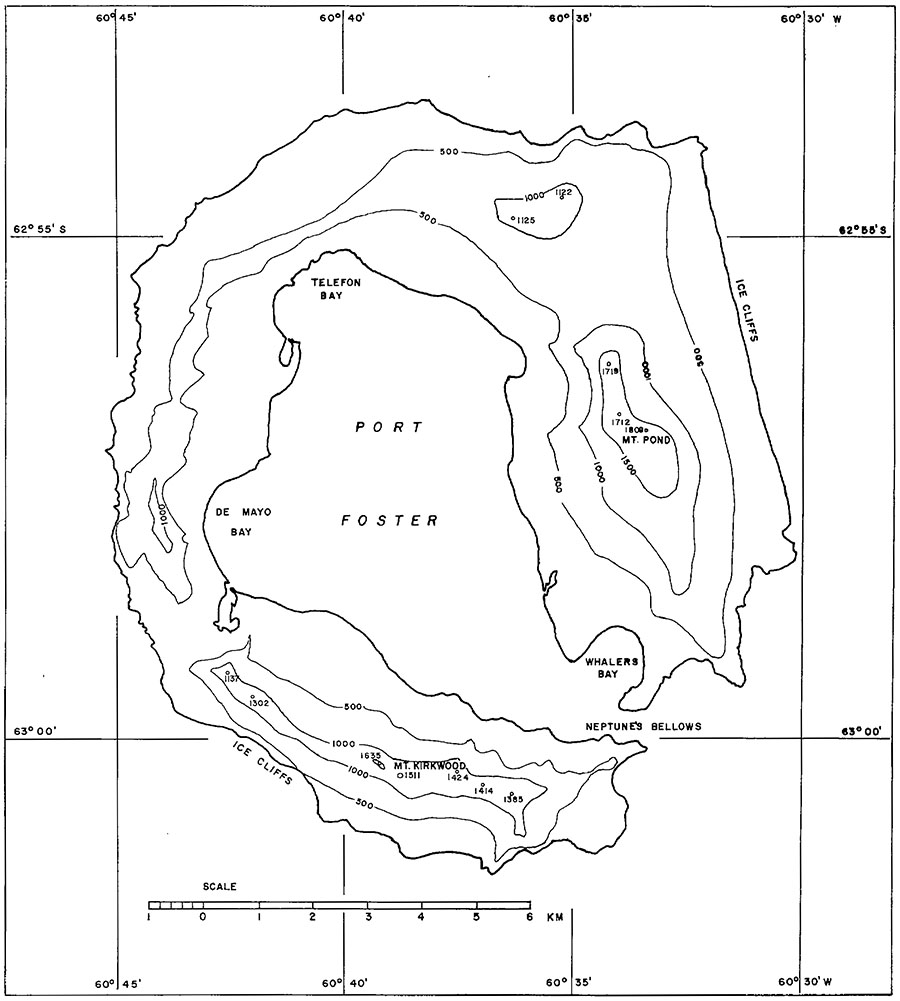

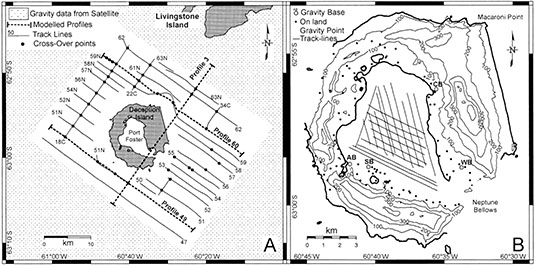

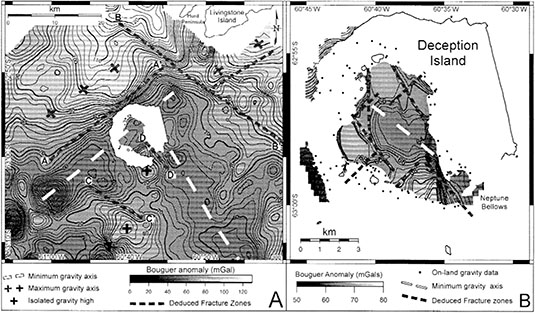

[Image: Deception Island, from Millett G. Morgan’s September 1960 paper An Island as a Natural Very-Low-Frequency Transmitting Antenna]. [Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)].

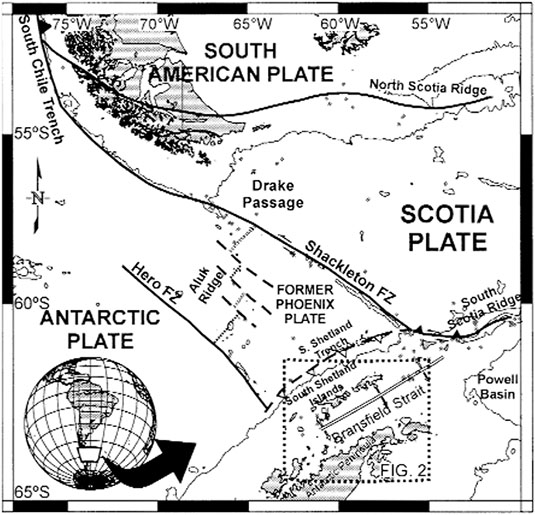

[Image: A map of Deception Island, taken from an otherwise unrelated paper called “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” published in Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

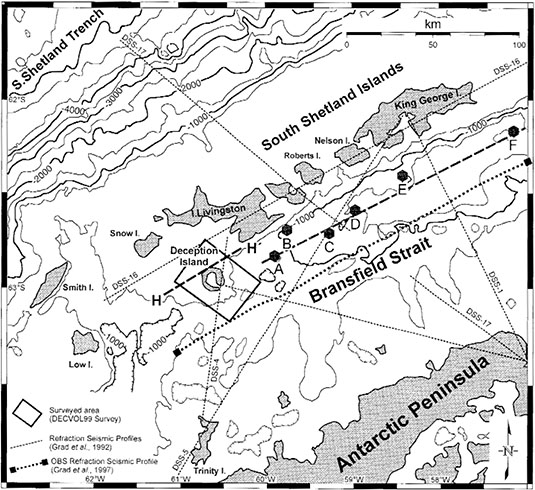

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)]. [Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

[Image: Deception Island, from “Upper crustal structure of Deception Island area (Bransfield Strait, Antarctica) from gravity and magnetic modelling,” Antarctic Science (2005)].

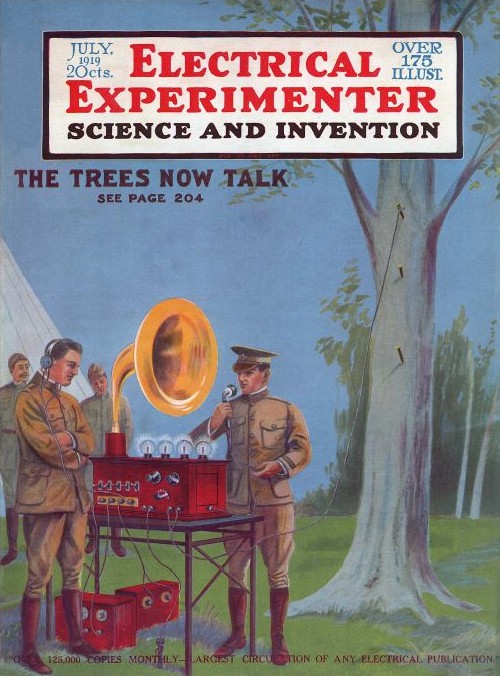

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

[Image: “The Trees Now Talk” cover story in

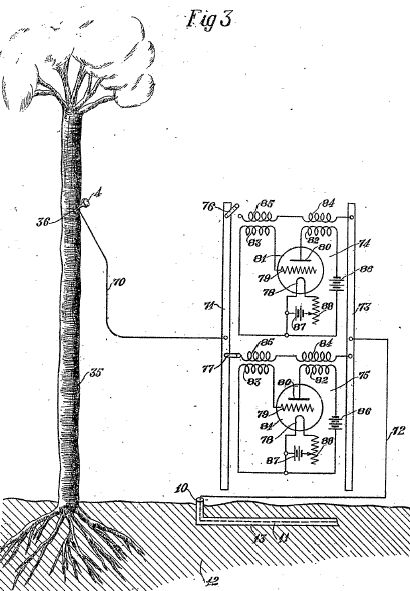

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via

[Images: From George Owen Squire’s British Patent Specification #149,917, via  [Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Researching the possibility that whole forests could be used as radio stations—broadcasting weather reports, news from the front lines of war, and much else besides—is described by Scientific American as performing “tree radio work.” Image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: A tree in the Panamanian rain forest wired up as a sending-receiving antenna; from IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)]. [Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Inside the Panamanian jungle-radio Test Zone; image via IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation (January 1975)].

[Image: Random sound file using

[Image: Random sound file using