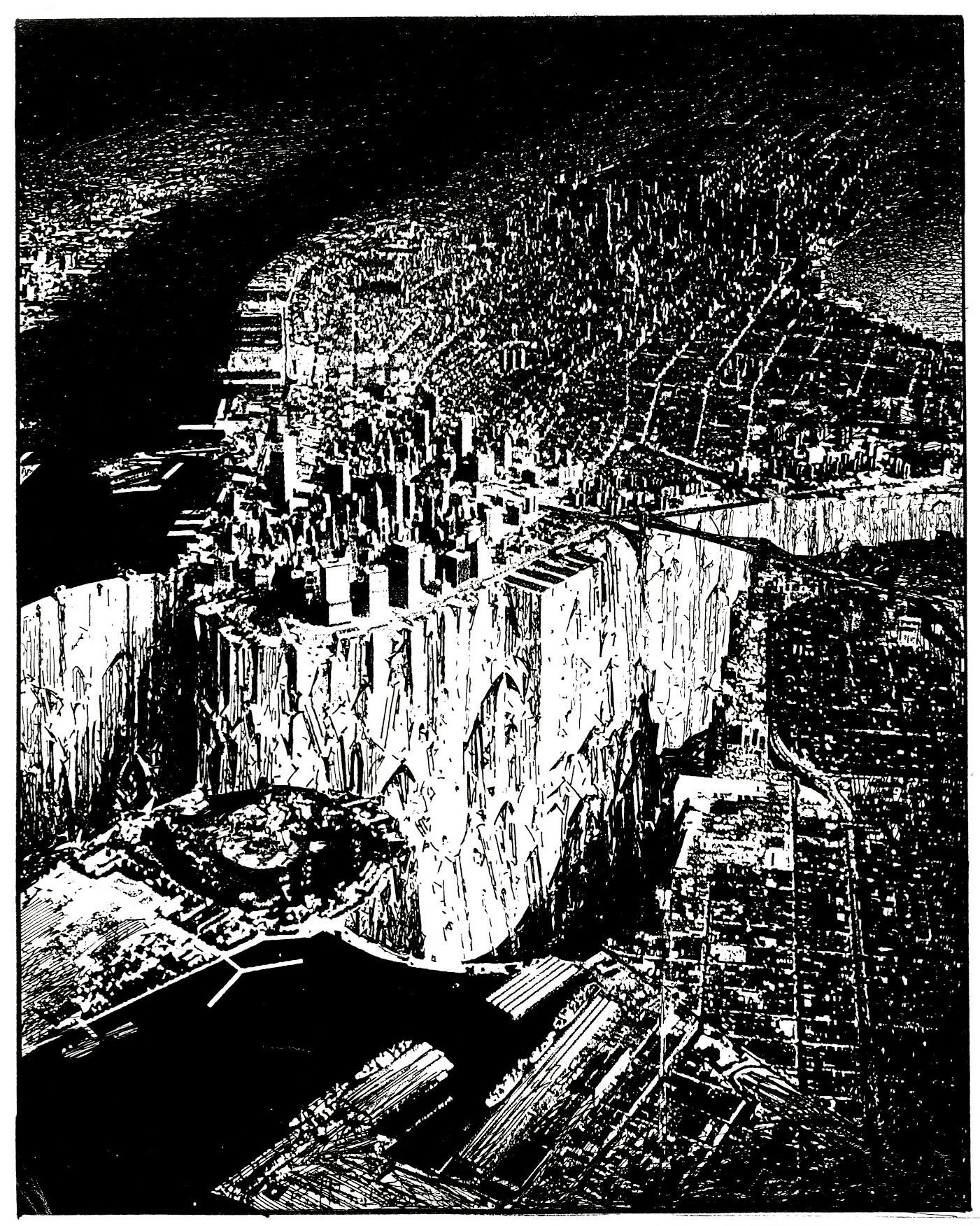

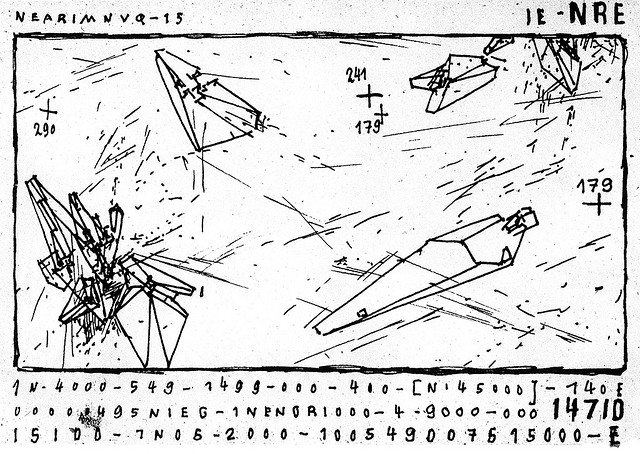

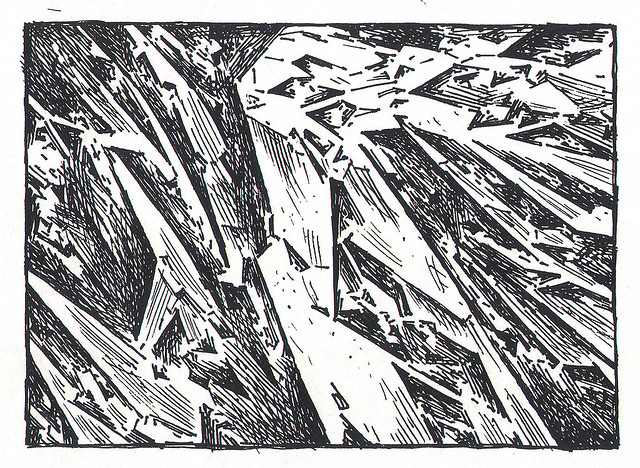

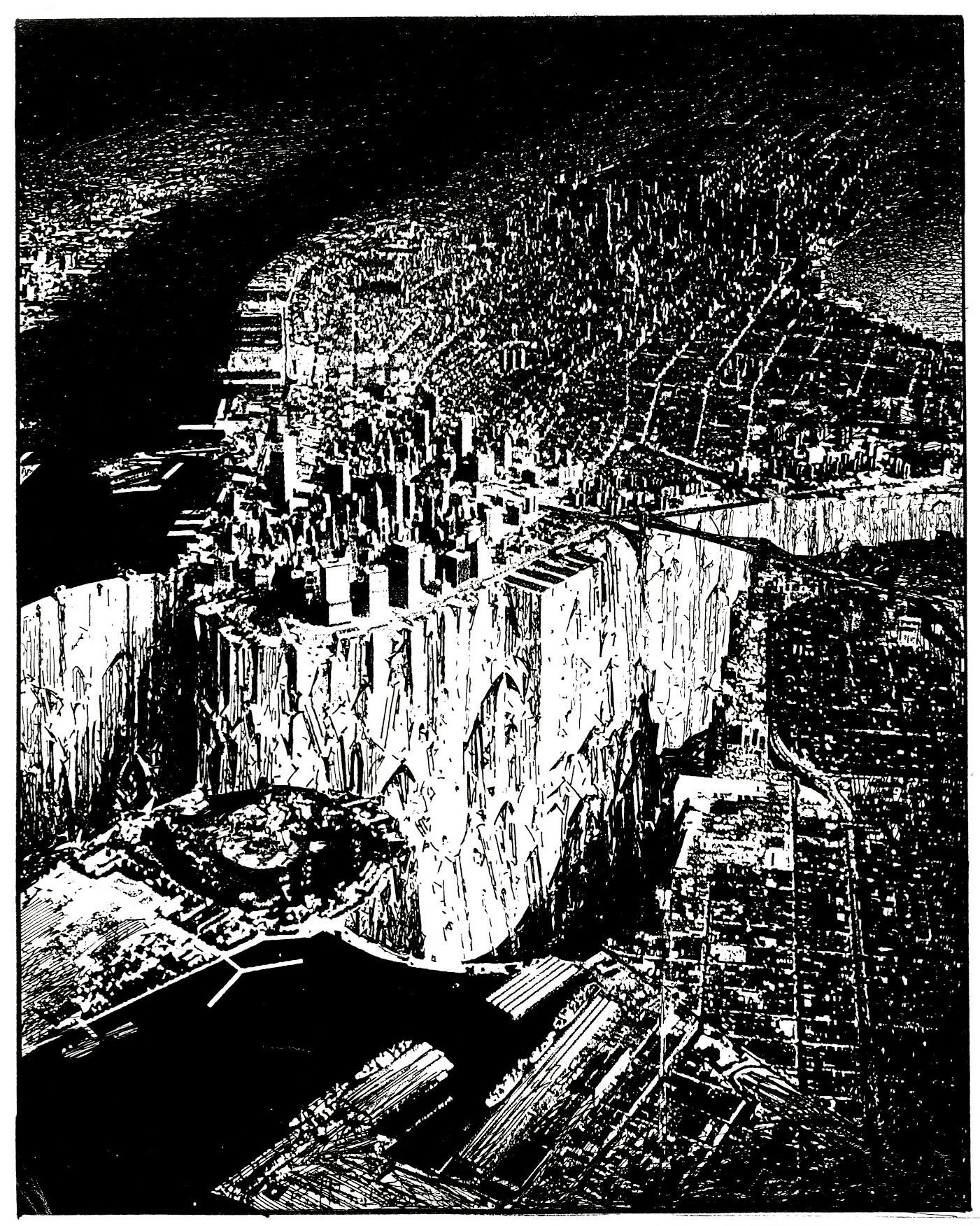

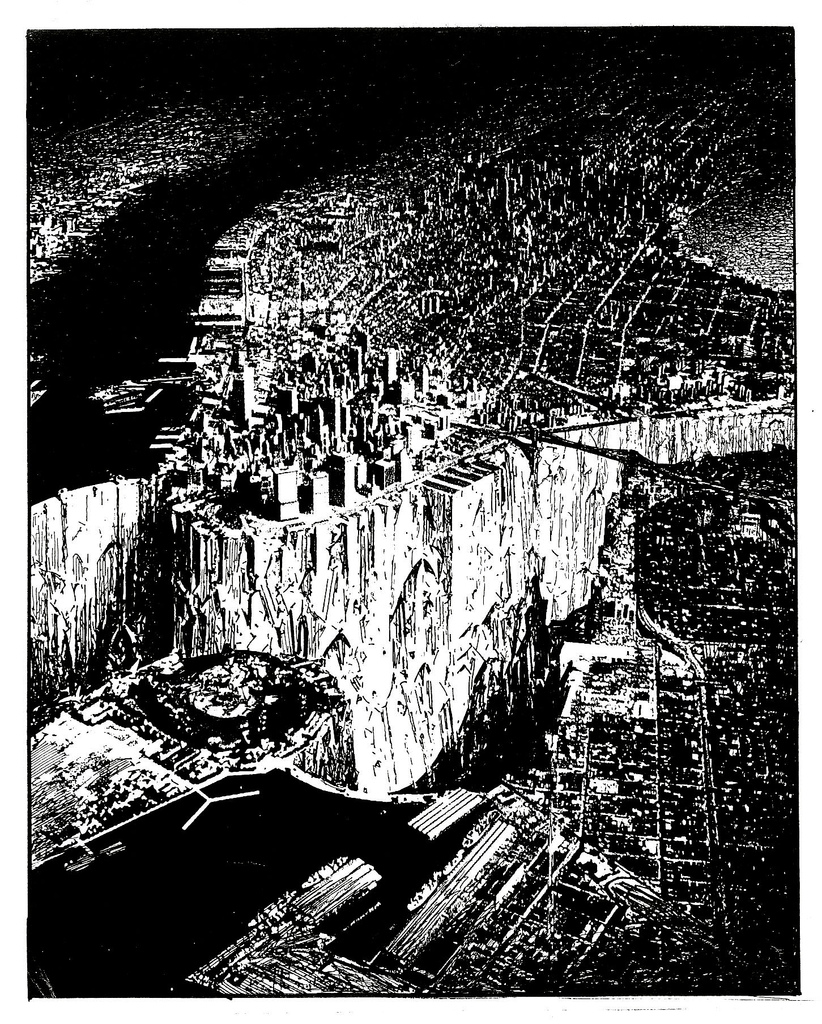

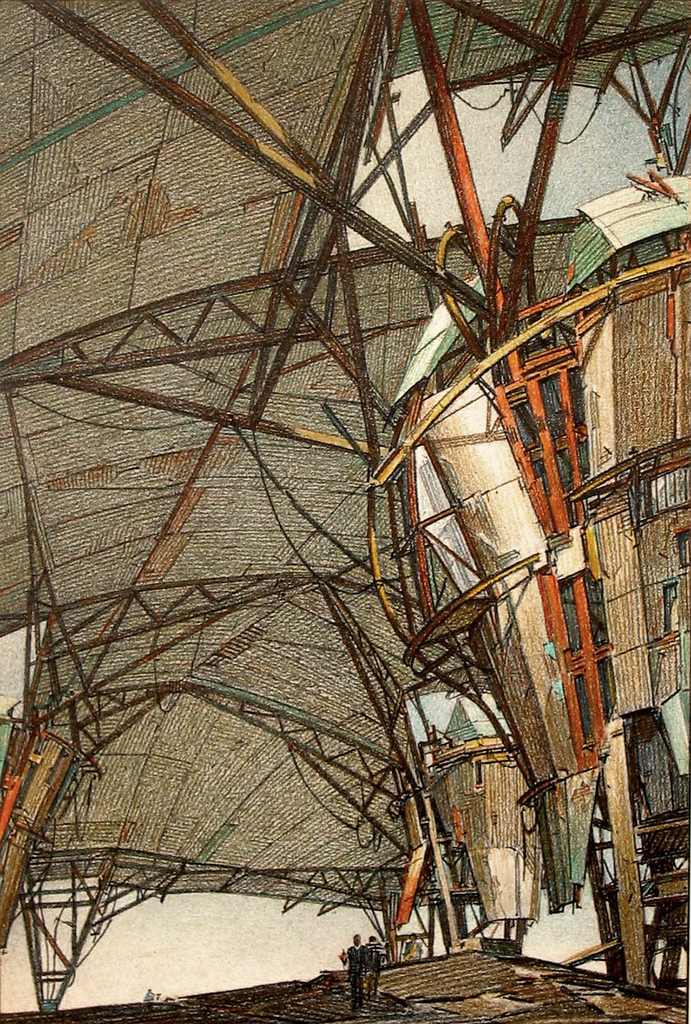

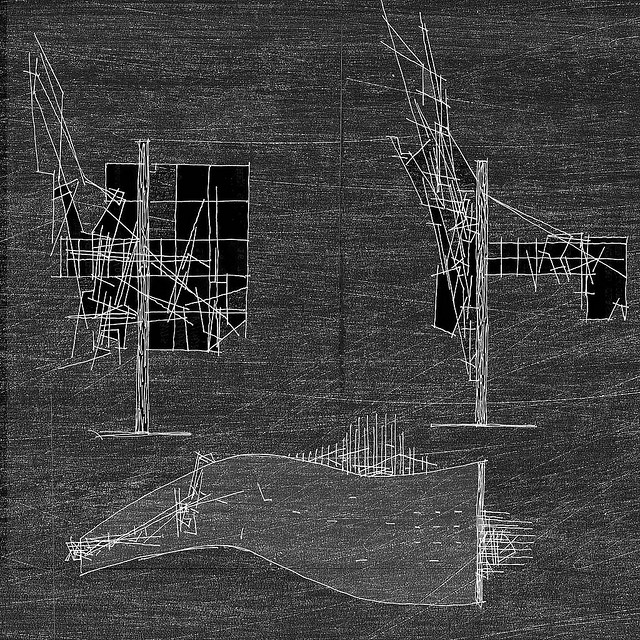

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view larger].

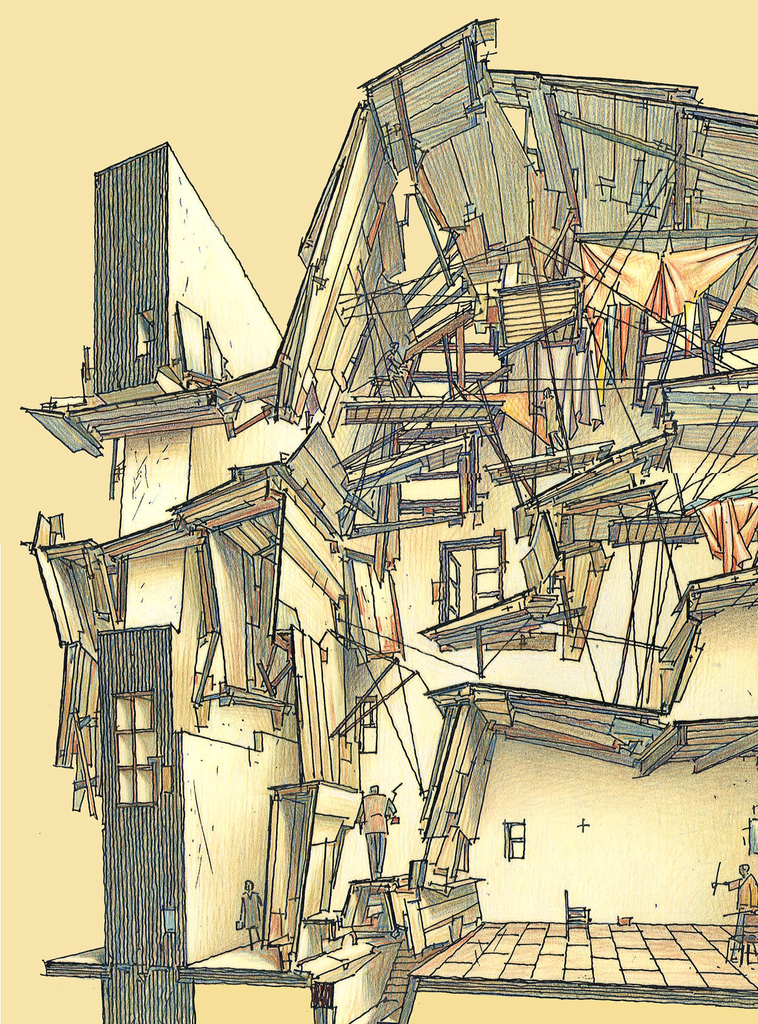

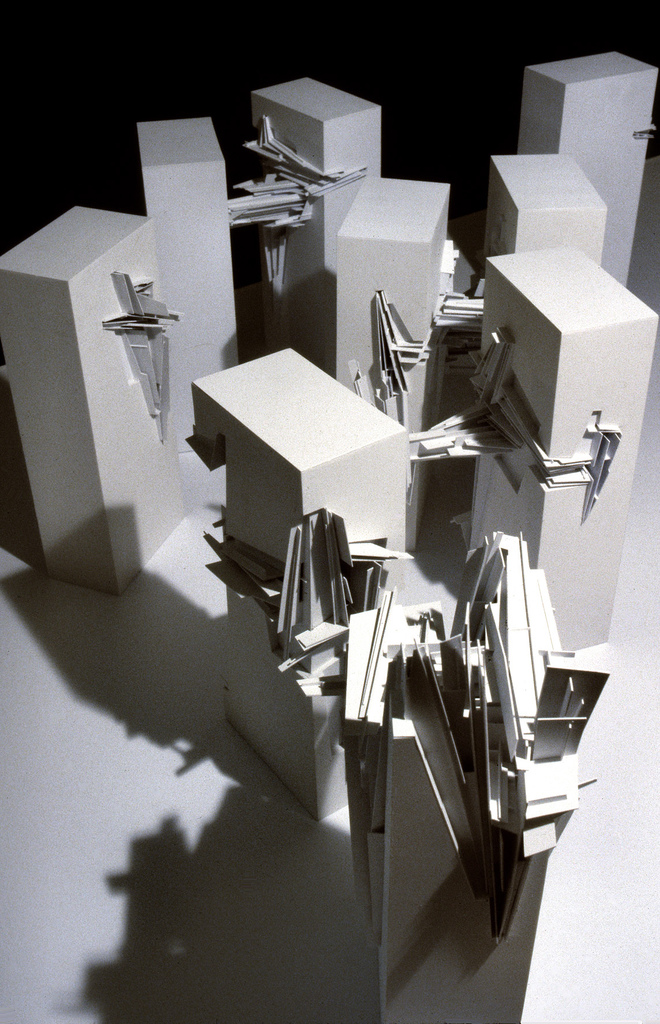

Lebbeus Woods is one of the first architects I knew by name – not Frank Lloyd Wright or Mies van der Rohe, but Lebbeus Woods – and it was Woods’s own technically baroque sketches and models, of buildings that could very well be machines (and vice versa), that gave me an early glimpse of what architecture could really be about.

Woods’s work is the exclamation point at the end of a sentence proclaiming that the architectural imagination, freed from constraints of finance and buildability, should be uncompromising, always. One should imagine entirely new structures, spaces without walls, radically reconstructing the outermost possibilities of the built environment.

If need be, we should re-think the very planet we stand on.

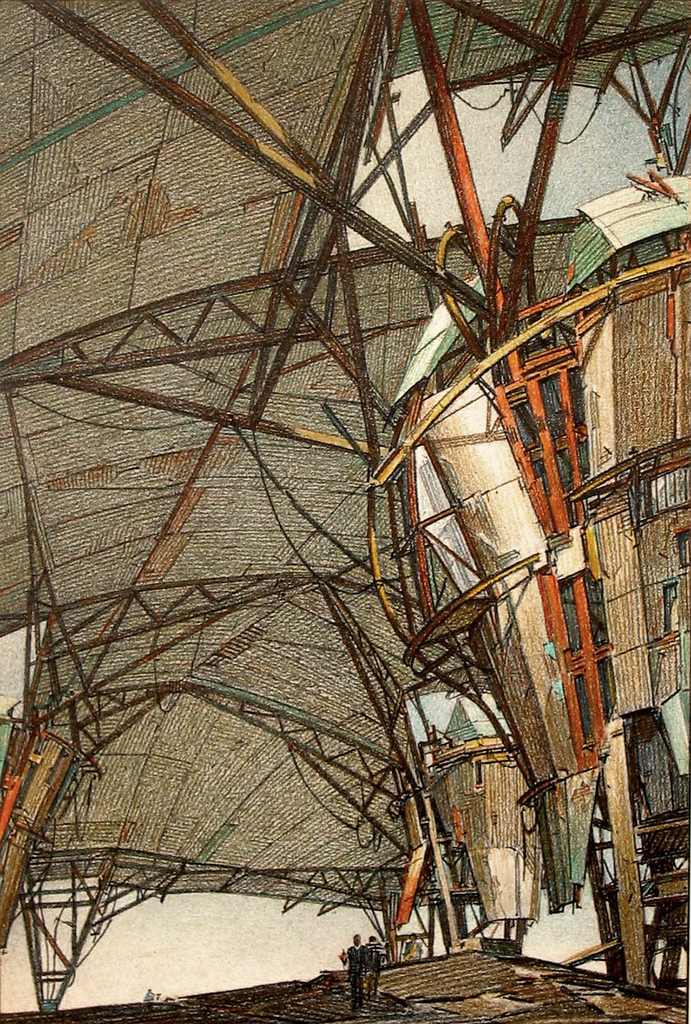

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

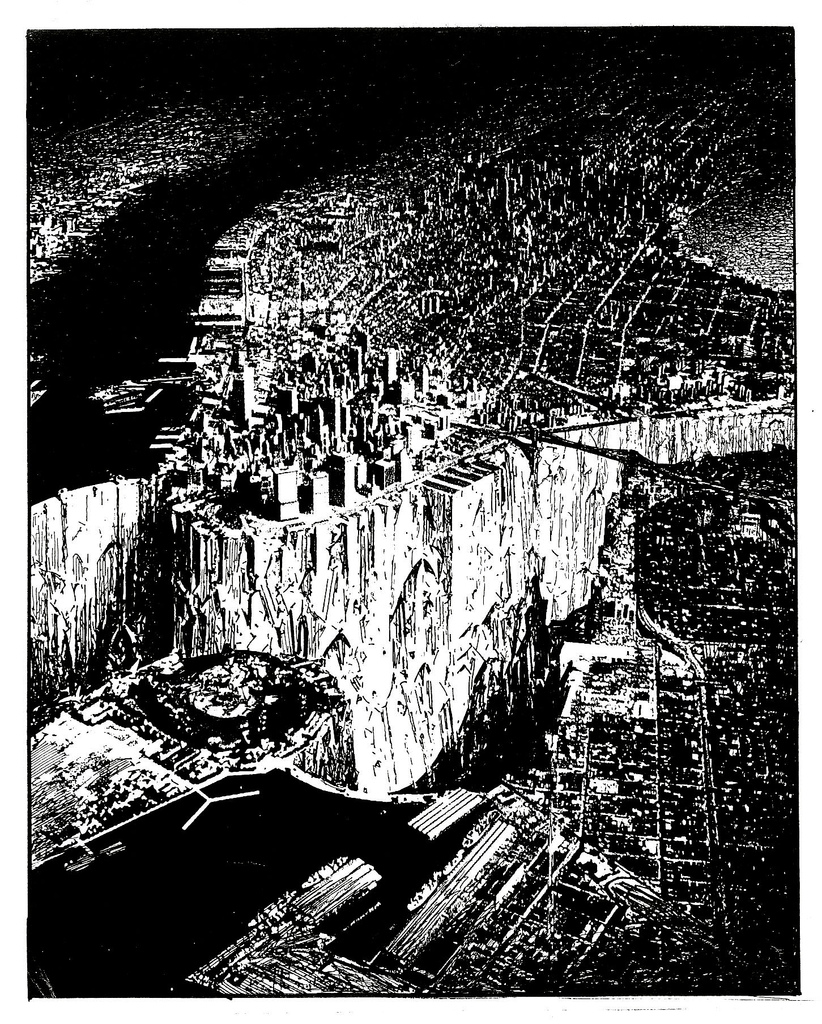

Of course, Woods is usually considered the avant-garde of the avant-garde, someone for whom architecture and science fiction – or urban planning and exhilarating, uncontained speculation – are all but one and the same. His work is experimental architecture in its most powerful, and politically provocative, sense.

Genres cross; fiction becomes reflection; archaeology becomes an unpredictable form of projective technology; and even the Earth itself gains an air of the non-terrestrial.

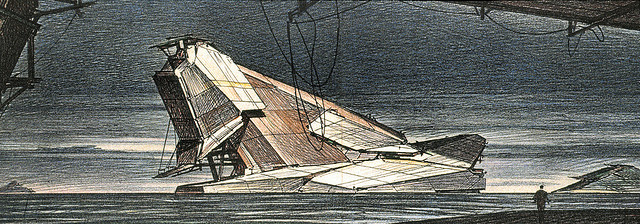

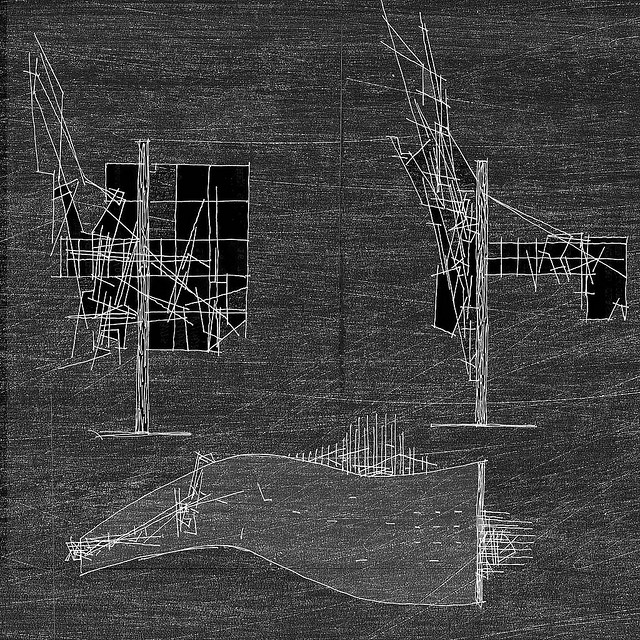

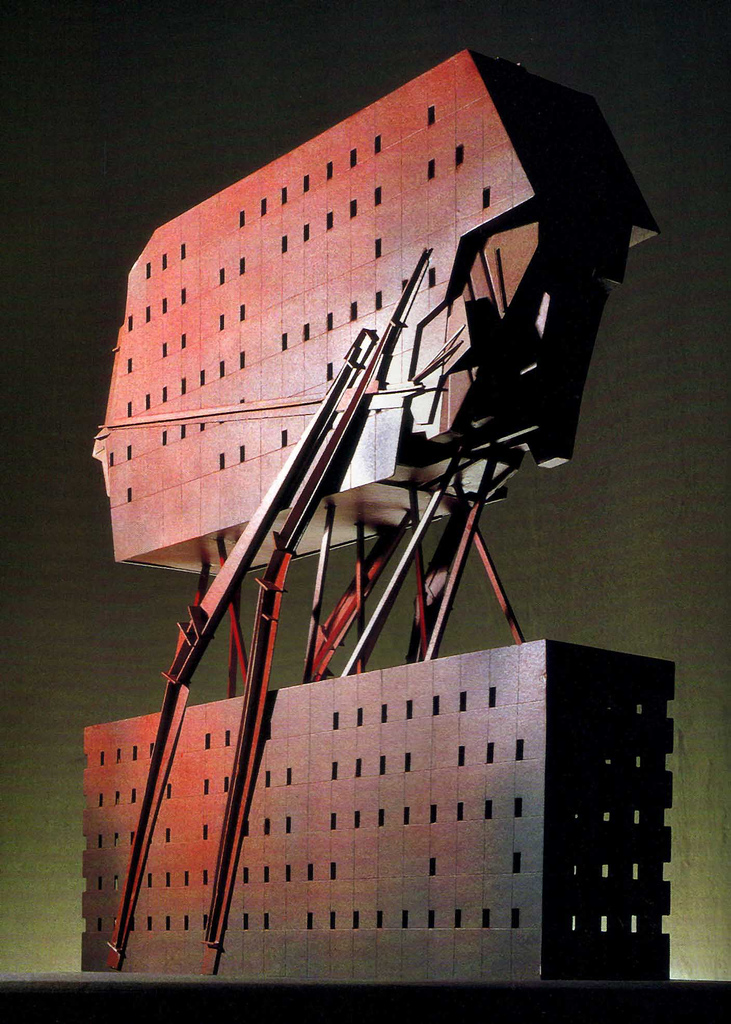

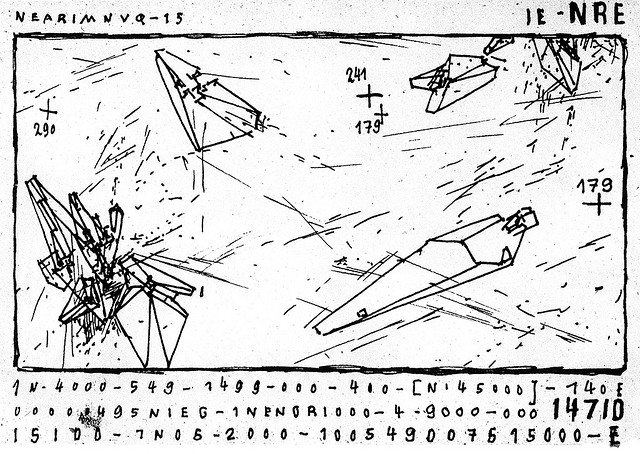

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

One project by Woods, in particular, captured my imagination – and, to this day, it just floors me. I love this thing. In 1980, Woods proposed a tomb for Albert Einstein – the so-called Einstein Tomb (collected here) – inspired by Boullée’s famous Cenotaph for Newton.

But Woods’s proposal wasn’t some paltry gravestone or intricate mausoleum in hewn granite: it was an asymmetrical space station traveling on the gravitational warp and weft of infinite emptiness, passing through clouds of mutational radiation, riding electromagnetic currents into the void.

The Einstein Tomb struck me as such an ingenious solution to an otherwise unremarkable problem – how to build a tomb for an historically titanic mathematician and physicist – that I’ve known who Lebbeus Woods is ever since.

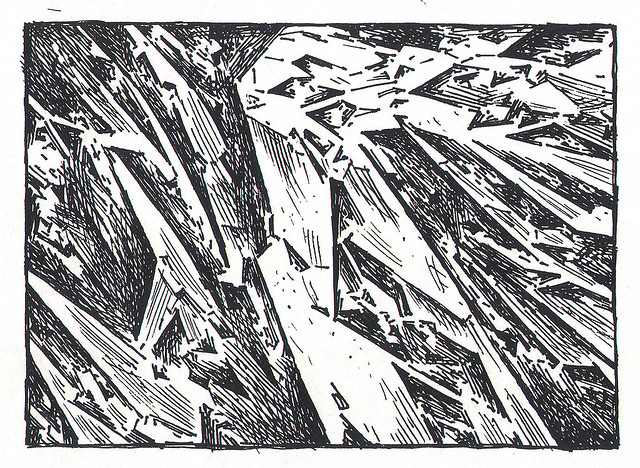

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

So when the opportunity came to talk to Lebbeus about one image that he produced nearly a decade ago, I continued with the questions; the result is this interview, which happily coincides with the launch of Lebbeus’s own website – his first – at lebbeuswoods.net. That site contains projects, writings, studio reports, and some external links, and it’s worth bookmarking for later exploration.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view larger].

In the following Q&A, then, Woods talks to BLDGBLOG about the geology of Manhattan; the reconstruction of urban warzones; politics, walls, and cooperative building projects in the future-perfect tense; and the networked forces of his most recent installations.

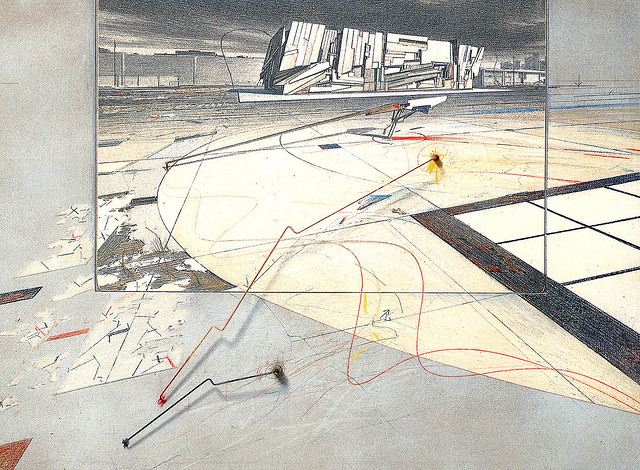

• • •BLDGBLOG: First, could you explain the origins of the

Lower Manhattan image?

Lebbeus Woods: This was one of those occasions when I got a request from a magazine – which is very rare. In 1999, Abitare was making a special issue on New York City, and they invited a number of architects – like Steven Holl, Rafael Viñoly, and, oh god, I don’t recall. Todd Williams and Billie Tsien. Michael Sorkin. Myself. They invited us to make some sort of comment about New York. So I wrote a piece – probably 1000 words, 800 words – and I made the drawing.

I think the main thought I had, in speculating on the future of New York, was that, in the past, a lot of discussions had been about New York being the biggest, the greatest, the best – but that all had to do with the size of the city. You know, the size of the skyscrapers, the size of the culture, the population. So I commented in the article about Le Corbusier’s infamous remark that your skyscrapers are too small. Of course, New York dwellers thought he meant, oh, they’re not tall enough – but what he was referring to was that they were too small in their ground plan. His idea of the Radiant City and the Ideal City – this was in the early 30s – was based on very large footprints of buildings, separated by great distances, and, in between the buildings in his vision, were forests, parks, and so forth. But in New York everything was cramped together because the buildings occupied such a limited ground area. So Le Corbusier was totally misunderstood by New Yorkers who thought, oh, our buildings aren’t tall enough – we’ve got to go higher! Of course, he wasn’t interested at all in their height – more in their plan relationship. Remember, he’s the guy who said, the plan is the generator.

So I was speculating on the future of the city and I said, well, obviously, compared to present and future cities, New York is not going to be able to compete in terms of size anymore. It used to be a large city, but now it’s a small city compared with São Paulo, Mexico City, Kuala Lumpur, or almost any Asian city of any size. So I said maybe New York can establish a new kind of scale – and the scale I was interested in was the scale of the city to the Earth, to the planet. I made the drawing as a demonstration of the fact that Manhattan exists, with its towers and skyscrapers, because it sits on a rock – on a granite base. You can put all this weight in a very small area because Manhattan sits on the Earth. Let’s not forget that buildings sit on the Earth.

I wanted to suggest that maybe lower Manhattan – not lower downtown, but lower in the sense of below the city – could form a new relationship with the planet. So, in the drawing, you see that the East River and the Hudson are both dammed. They’re purposefully drained, as it were. The underground – or lower Manhattan – is revealed, and, in the drawing, there are suggestions of inhabitation in that lower region.

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view larger].

So it was a romantic idea – and the drawing is very conceptual in that sense.

But the exposure of the rock base, or the underground condition of the city, completely changes the scale relationship between the city and its environment. It’s peeling back the surface to see what the planetary reality is. And the new scale relationship is not about huge blockbuster buildings; it’s not about towers and skyscrapers. It’s about the relationship of the relatively small human scratchings on the surface of the earth compared to the earth itself. I think that comes across in the drawing. It’s not geologically correct, I’m sure, but the idea is there.

There are a couple of other interesting features which I’ll just mention. One is that the only bridge I show is the Brooklyn Bridge. I don’t show the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, for instance. That’s just gone. And I don’t show the Manhattan Bridge or the Williamsburg Bridge, which are the other two bridges on the East River. On the Hudson side, it was interesting, because I looked carefully at the drawings – which I based on an aerial photograph of Manhattan, obviously – and the World Trade Center… something’s going on there. Of course, this was in 1999, and I’m not a prophet and I don’t think that I have any particular telepathic or clairvoyant abilities [laughs], but obviously the World Trade Center has been somehow diminished, and there are things floating in the Hudson next to it. I’m not sure exactly what I had in mind – it was already several years ago – except that some kind of transformation was going to happen there.

BLDGBLOG: That’s actually one of the things I like so much about your work: you re-imagine cities and buildings and whole landscapes as if they have undergone some sort of potentially catastrophic transformation – be it a war or an earthquake, etc. – but you don’t respond to those transformations by designing, say, new prefab refugee shelters or more durable tents. You respond with what I’ll call science fiction: a completely new order of things – a new way of organizing and thinking about space. You posit something radically different than what was there before. It’s exciting.

Woods: Well, I think that, for instance, in Sarajevo, I was trying to speculate on how the war could be turned around, into something that people could build the new Sarajevo on. It wasn’t about cleaning up the mess or fixing up the damage; it was more about a transformation in the society and the politics and the economics through architecture. I mean, it was a scenario – and, I suppose, that was the kind of movie aspect to it. It was a “what if?”

I think there’s not enough of that thinking today in relation to cities that have been faced with sudden and dramatic – even violent – transformations, either because of natural or human causes. But we need to be able to speculate, to create these scenarios, and to be useful in a discussion about the next move. No one expects these ideas to be easily implemented. It’s not like a practical plan that you should run out and do. But, certainly, the new scenario gives you a chance to investigate a direction. Of course, being an architect, I’m very interested in the specifics of that direction – you know, not just a verbal description but: this is what it might look like.

So that was the approach in Sarajevo – as well as in this drawing of Lower Manhattan, as I called it.

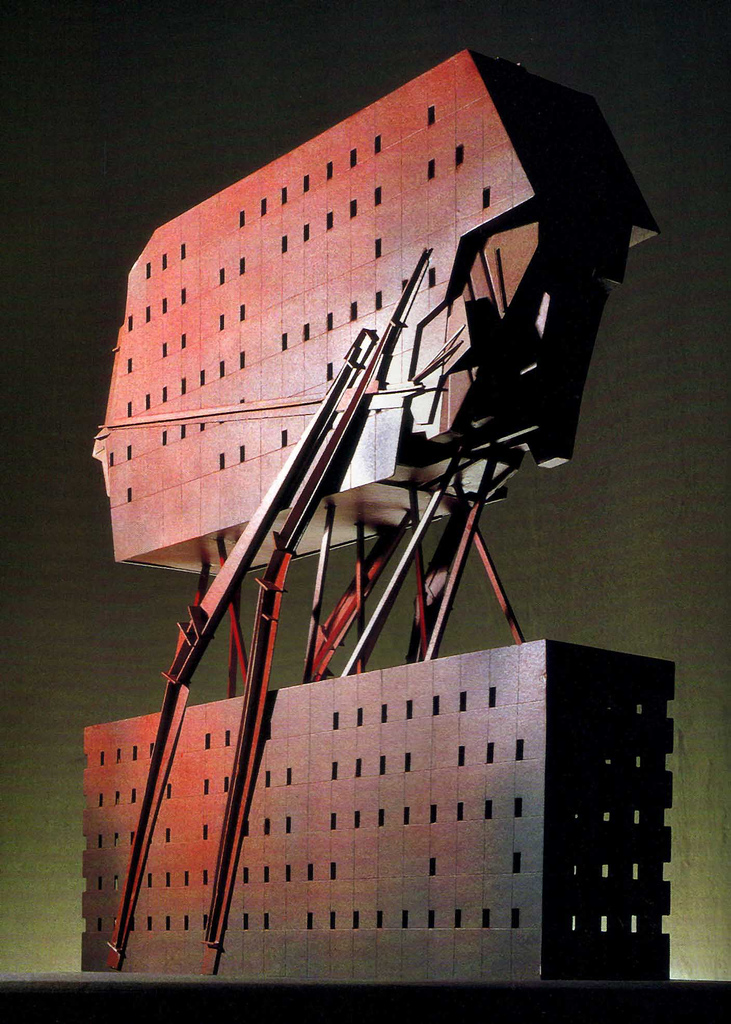

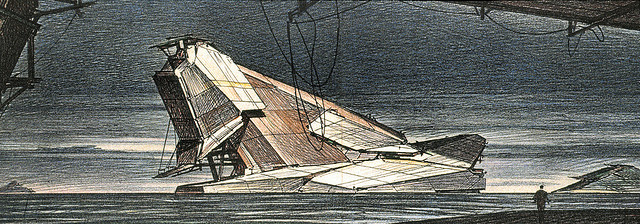

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

BLDGBLOG: Part of that comes from recognizing architecture as its own kind of genre. In other words, architecture has the ability, rivaling literature, to imagine and propose new, alternative routes out of the present moment. So architecture isn’t just buildings, it’s a system of entirely re-imagining the world through new plans and scenarios.

Woods: Well, let me just back up and say that architecture is a multi-disciplinary field, by definition. But, as a multi-disciplinary field, our ideas have to be comprehensive; we can’t just say: “I’ve got a new type of column that I think will be great for the future of architecture.”

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Woods: Maybe it will be great – but it’s not enough. I think architects – at least those inclined to understand the multi-disciplinarity and the comprehensive nature of their field – have to visualize something that embraces all these political, economic, and social changes. As well as the technological. As well as the spatial.

But we’re living in a very odd time for the field. There’s a kind of lack of discourse about these larger issues. People are hunkered down, looking for jobs, trying to get a building. It’s a low point. I don’t think it will stay that way. I don’t think that architects themselves will allow that. After all, it’s architects who create the field of architecture; it’s not society, it’s not clients, it’s not governments. I mean, we architects are the ones who define what the field is about, right?

So if there’s a dearth of that kind of thinking at the moment, it’s because architects have retreated – and I’m sure a coming generation is going to say: hey, this retreat is not good. We’ve got to imagine more broadly. We have to have a more comprehensive vision of what the future is.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

BLDGBLOG: In your own work – and I’m thinking here of the Korean DMZ project or the Israeli wall-game – this “more comprehensive vision” of the future also involves rethinking political structures. Engaging in society not just spatially, but politically. Many of the buildings that you’ve proposed are more than just buildings, in other words; they’re actually new forms of political organization.

Woods: Yeah. I mean, obviously, the making of buildings is a huge investment of resources of various kinds. Financial, as well as material, and intellectual, and emotional resources of a whole group of people get involved in a particular building project. And any time you get a group, you’re talking about politics. To me politics means one thing: How do you change your situation? What is the mechanism by which you change your life? That’s politics. That’s the political question. It’s about negotiation, or it’s about revolution, or it’s about terrorism, or it’s about careful step-by-step planning – all of this is political in nature. It’s about how people, when they get together, agree to change their situation.

As I wrote some years back, architecture is a political act, by nature. It has to do with the relationships between people and how they decide to change their conditions of living. And architecture is a prime instrument of making that change – because it has to do with building the environment they live in, and the relationships that exist in that environment.

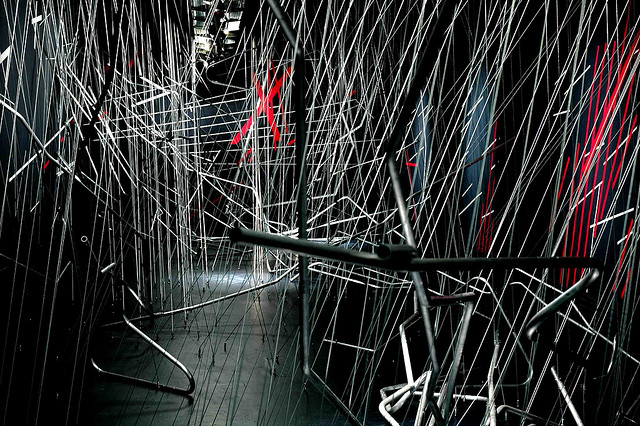

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

BLDGBLOG: There’s also the incredibly interesting possibility that a building project, once complete, will actually change the society that built it. It’s the idea that a building – a work of architecture – could directly catalyze a transformation, so that the society that finishes building something is not the same society that set out to build it in the first place. The building changes them.

Woods: I love that. I love the way you put it, and I totally agree with it. I think, you know, architecture should not just be something that follows up on events but be a leader of events. That’s what you’re saying: That by implementing an architectural action, you actually are making a transformation in the social fabric and in the political fabric. Architecture becomes an instigator; it becomes an initiator.

That, of course, is what I’ve always promoted – but it’s the most difficult thing for people to do. Architects say: well, it’s my client, they won’t let me do this. Or: I have to do what my client wants. That’s why I don’t have any clients! [laughter] It’s true.

Because at least I can put the ideas out there and somehow it might seep through, or filter through, to another level.

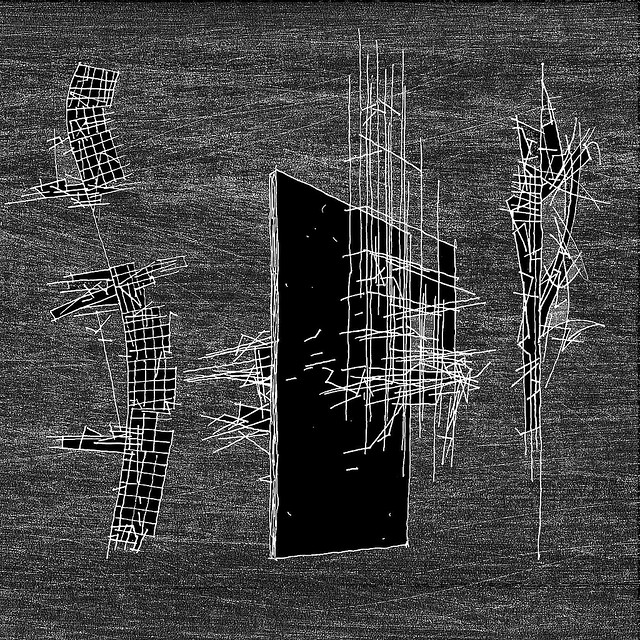

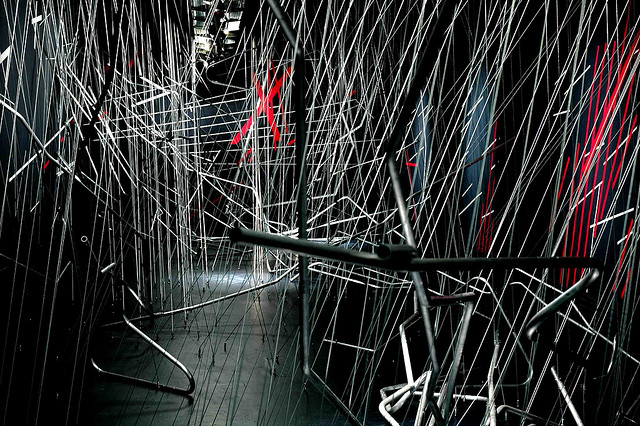

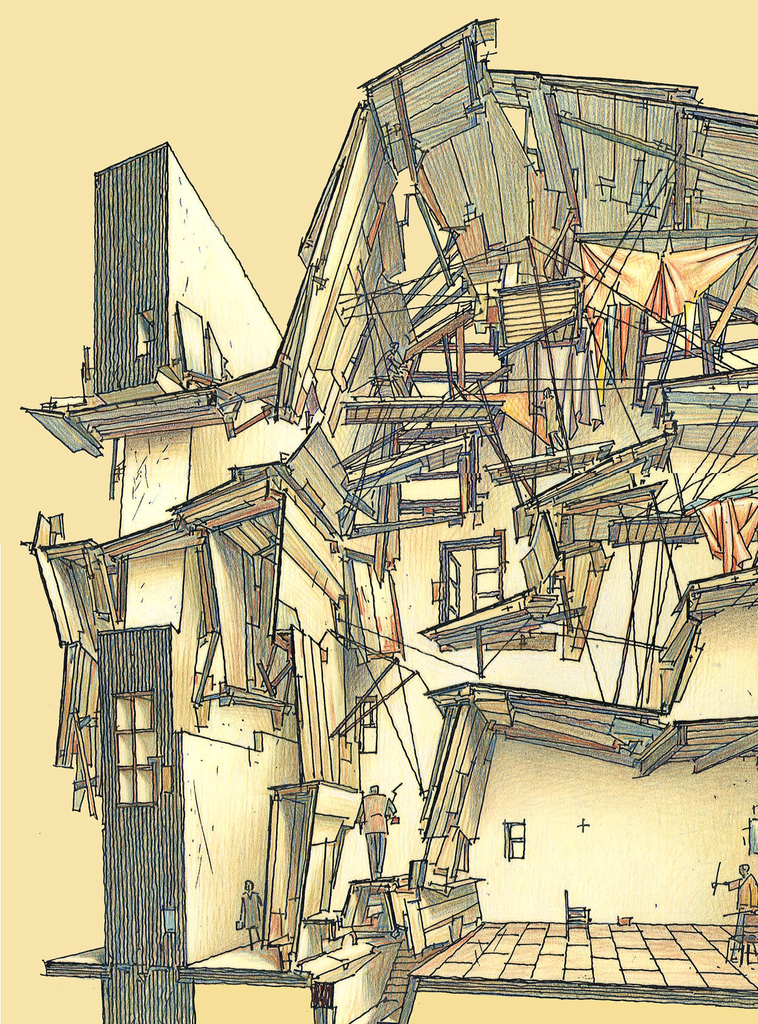

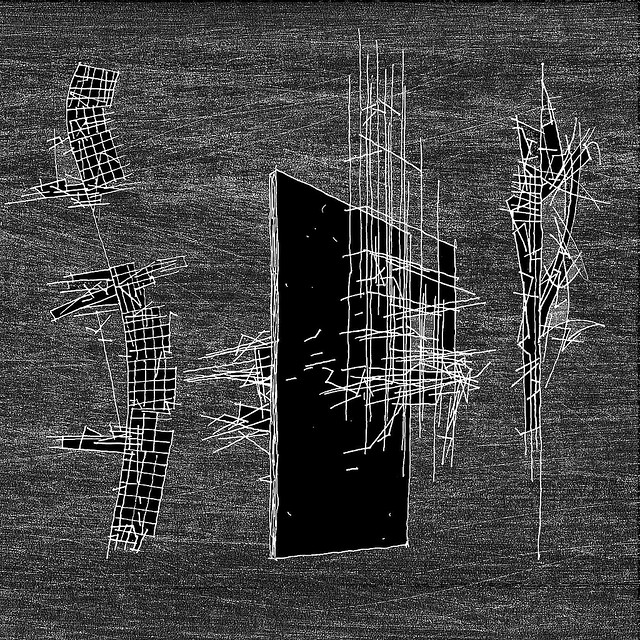

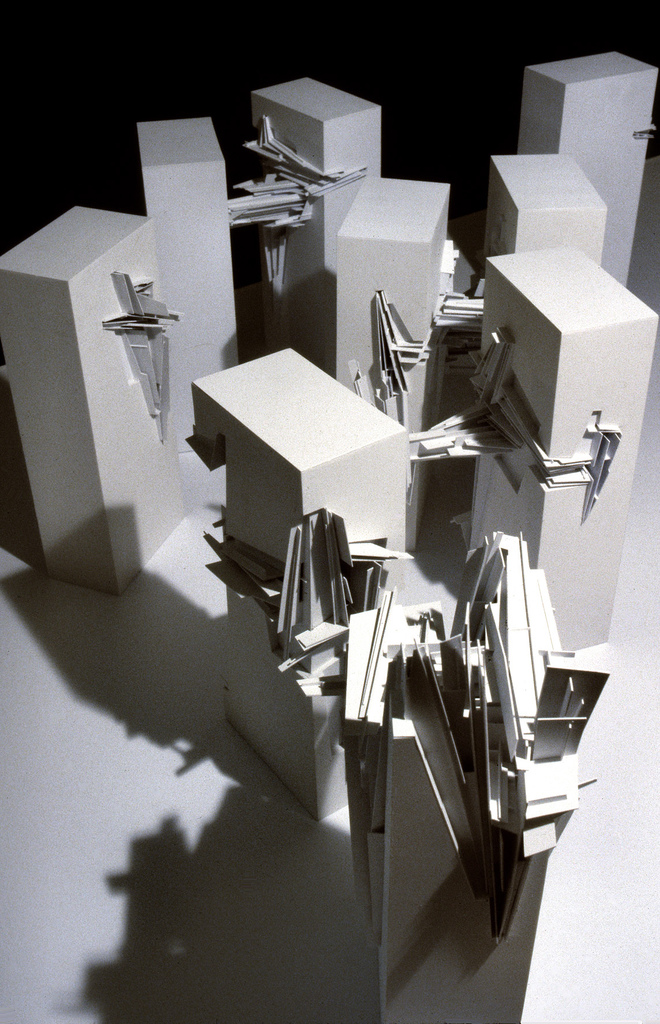

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

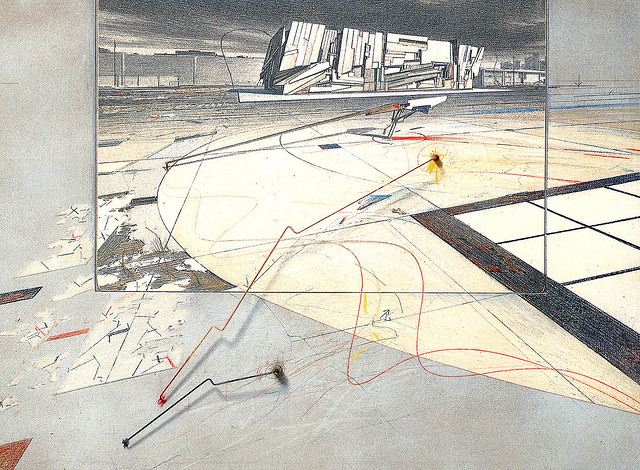

BLDGBLOG: Finally, it seems like a lot of the work you’ve been doing for the past few years – in Vienna, especially – has been a kind of architecture without walls. It’s almost pure space. In other words, instead of walls and floors and recognizable structures, you’ve been producing networks and forces and tangles and clusters – an abstract space of energy and directions. Is that an accurate way of looking at your recent work – and, if so, is this a purely aesthetic exploration, or is this architecture without walls meant to symbolize or communicate a larger political message?

Woods: Well, look – if you go back through my projects over the years, probably the least present aspect is the idea of property lines. There are certainly boundaries – spatial boundaries – because, without them, you can’t create space. But the idea of fencing off, or of compartmentalizing – or the capitalist ideal of private property – has been absent from my work over the last few years.

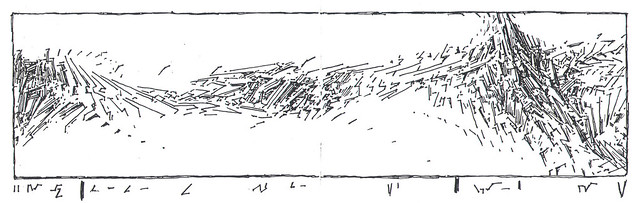

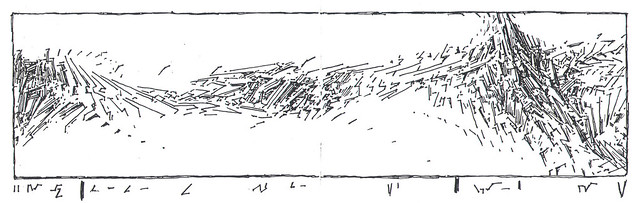

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

I think in my more recent work, certainly, there are still boundaries. There are still edges. But they are much more porous, and the property lines… [laughs] are even less, should we say, defined or desired.

So the more recent work – like in Vienna, as you mentioned – is harder for people to grasp. Back in the early 90s I was confronting particular situations, and I was doing it in a kind of scenario way. I made realistic-looking drawings of places – of situations – but now I’ve moved into a purely architectonic mode. I think people probably scratch their heads a little bit and say: well, what is this? But I’m glad you grasp it – and I hope my comments clarify at least my aspirations.

Probably the political implication of that is something about being open – encouraging what I call the lateral movement and not the vertical movement of politics. It’s the definition of a space through a set of approximations or a set of vibrations or a set of energy fluctuations – and that has everything to do with living in the present.

All of those lines are in flux. They’re in movement, as we ourselves develop and change.

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

• • •BLDGBLOG owes a huge thanks to Lebbeus Woods, not only for having this conversation but for proving over and over again that architecture can and should always be a form of

radical reconstruction, unafraid to take on buildings, cities, worlds – whole planets.

For more images, meanwhile, including much larger versions of all the ones that appear here, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s Lebbeus Woods Flickr set. Also consider stopping by Subtopia for an enthusiastic recap of Lebbeus’s appearance at Postopolis! last Spring; and by City of Sound for Dan Hill’s synopsis of the same event.

[Image: Via Wikipedia].

[Image: Via Wikipedia]. [Image: Via with reference to death].

[Image: Via with reference to death].

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: The World Trade Center towers, photographer unknown].

[Image: The World Trade Center towers, photographer unknown].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].