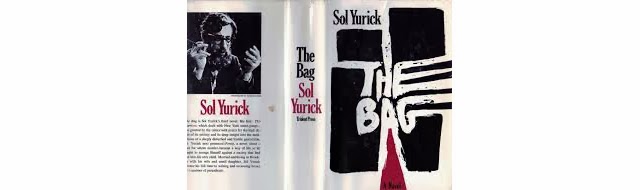

I interviewed novelist Sol Yurick back in March 2009. Rather than publish the interview on BLDGBLOG as I should have, however, I thought I’d try to find a place for it elsewhere, and began pitching it to a few design magazines. Yurick, after all, was the author of The Warriors—later turned into the cult classic film of the same name, in which New York City is transformed into a ruined staging ground for elaborately costumed gangs—and he was a familiar enough figure amidst a particular crowd of underground readers and independent press aficionados, those of us who might gravitate more toward Autonomedia pamphlets, for example, where you’d find Yurick’s strange and prescient Metatron: The Recording Angel, than anything on the bestseller list.

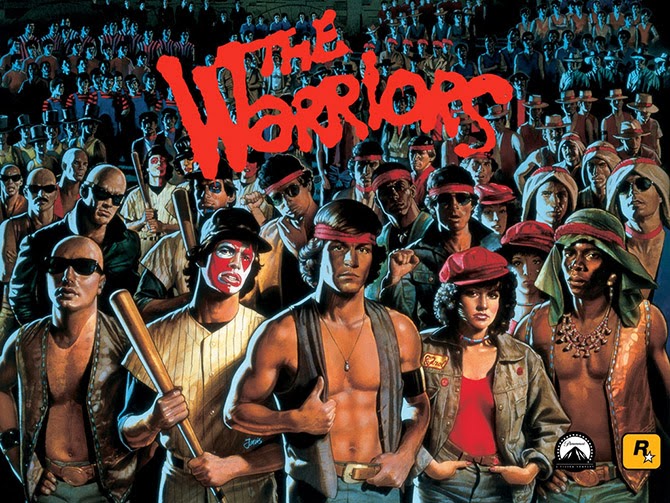

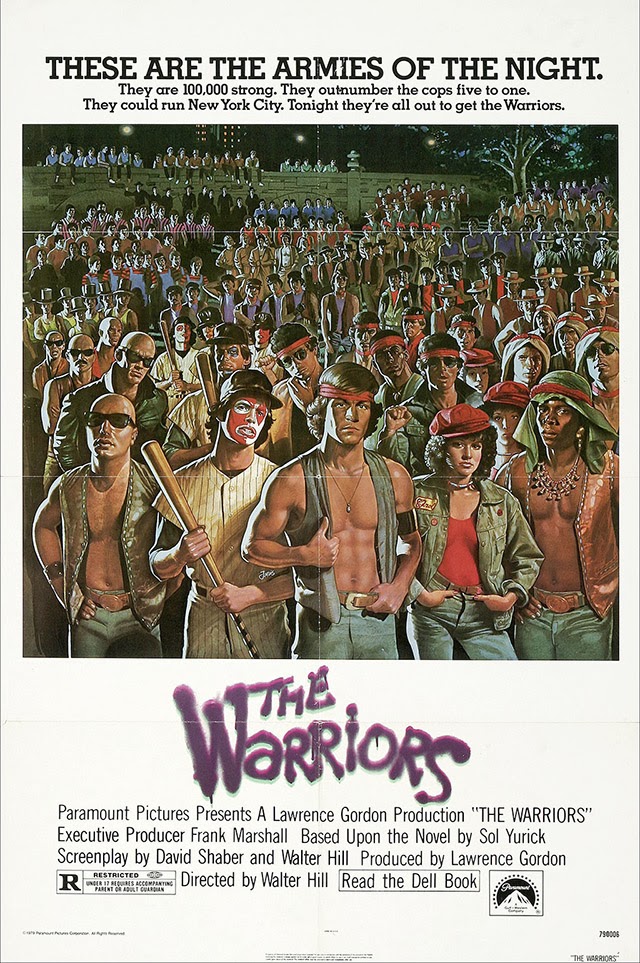

Looked at one way, The Warriors tells the story of a city gone out of control, become feral, taken over by criminal gangs and faceless police organizations, its infrastructure half-abandoned or, at the very least, fallen into a state of Piranesian decay. The everyday lives of its residents whirl on, while these cartoon-like groups of armed militants spiral toward violence and disaster. Yurick was thus an urban author, I thought, suitable for urban and architectural publications, his insights on cities far more useful than your average TED Talk and about one ten-thousandth as exposed.

In the interview, published for the first time below, Yurick freely discussed the back-story for The Warriors, which was the question that had motivated me to contact him in the first place. But he also drifted into his interests in the global financial system, which, at that point in time, was melting down through a domino game of bad mortgages and Ponzi schemes, and he went on to offer an even more dizzying perspective on Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Dante, in Yurick’s unexpected retelling, had actually written a series of concentric financial allegories, tales of monetary wizardry starring lost, beautiful souls searching for one another amongst the impenetrable mathematics of paradise.

Along the way, we touched on Mexican drug cartels, the Trojan War, the United Nations, and a handful of forthcoming books that Yurick was still, he claimed, energetically working on at the time.

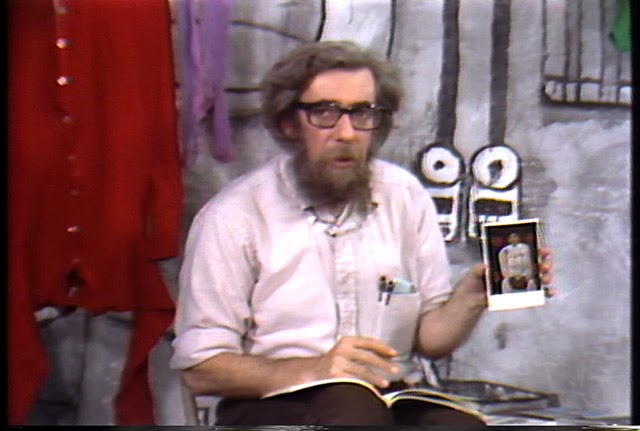

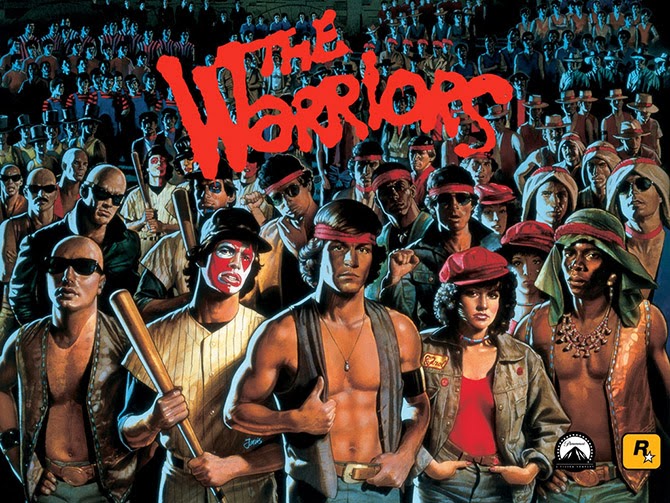

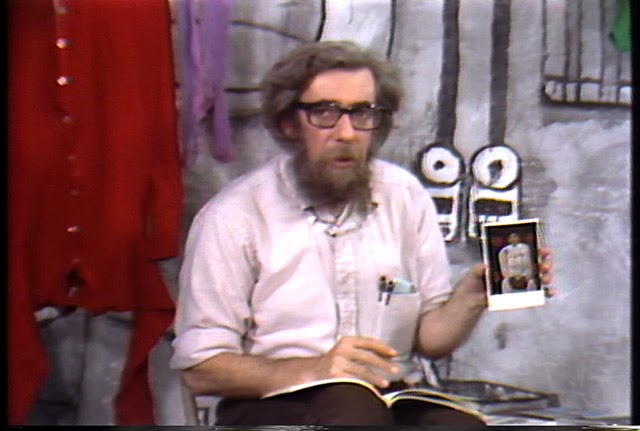

Image from Paper Tiger, via Sheepshead Bites

Image from Paper Tiger, via Sheepshead Bites

Alas, I pitched the wrong magazines and, soon thereafter, hit the road for a long period of travel and work; the interview simply disappeared into my hard drive and years went by. Then, worst of all, Yurick passed away in January of this year.

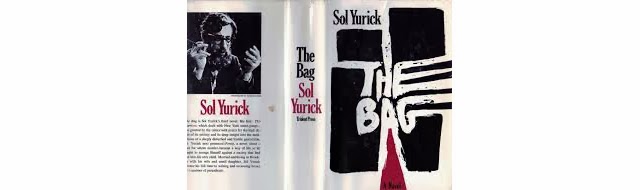

The New York Times described him as “a writer whose best-known work, the 1965 novel The Warriors, recast an ancient Greek battle as a tale of warring New York street gangs and earned a cult following in print, on film and eventually in a video game.” Writing for The Nation, Samuel Fromartz specifically referred to several “out-of-the-blue interview requests” that had popped up in Yurick’s latter years, asking him about, yes, The Warriors. As Fromartz writes, “despite the delight he got in its cult status, it did not mean a lot more to him” than his other books, The Warriors being simply one project among many.

And so this interview sat, unpublished, till I came across it again in my files recently and I thought I’d give it a second life online. It’s a fascinating discussion with an aging writer who unhesitatingly looked back at a long career of writing both fiction and political analysis, a life of deep reading and even a few eye-poppingly abstract interpretations of Dante.

What follows is the final edit of our conversation. Yurick was an engaged and pointed conversationalist, and, while I was obviously just another out-of-the-blue interviewer curious about the broken city of The Warriors, I hope this text does justice to his creative and sharp vision of the world.

So this is for Sol Yurick, 1925-2013.

* * *

BLDGBLOG: I’d love to start with the most basic question of all, which is to ask about the back-story behind The Warriors. What motivated you to write it when you did?

Sol Yurick: Well, initially it started off when I was talking about some ideas with a friend in college. I’d just finished reading Xenophon and the concept popped into my head. This was the early 1940s.

Then, later, maybe in the 1950s, I read Outlaws of the Marsh, and the combination of ritual and violence in Outlaws of the Marsh just took my breath away. Those things mixed—Xenophon, ritual violence, Outlaws of the Marsh—and, on top of all that, I had already been working on a novel of my own. I was trying to get it published and it kept getting rejected—maybe 37 times?

BLDGBLOG: Wow.

Yurick: To move on to the next step, I wrote The Warriors. I did it in about three weeks. By this time, a lot of these ideas had matured. I’d been thinking about the whole question of gangs. First of all, the youth gangs at that point in time, running into the 1950s and ’60s, had no economic basis whatsoever. They mostly came from poverty-stricken families. You remember the film Rebel Without a Cause, right? That kind of stuff. It was viewed as kind of a national problem.

However, there were also gangs that came out of the suburbs—gangs nobody had ever heard about. No sociologist had wrote about this. In fact, I was big on sociology at the time, especially the works of Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, the founders of modern sociology. I wanted to write about stuff that approached reality—that was based in social reality—and that was not bound by a lot of the clichés or conventions of fiction as I knew it. I wanted to deal with a different stratum of society, something that wasn’t getting the attention it deserved in fiction at the time.

By the time I was actually writing the book, though, the whole 1960s had already started, and I eventually had a different take on it. In the book, it’s really about making a revolution, not just a criminal gang taking over the city. After all, it takes place on July 4th! But, in the book, that holiday is like a slap in the face for my characters—at least that’s the vision of the gang leader, looking at all the things that keep these people down. It’s Independence Day—but independence for whom? Independence from what?

Since that time, I’ve thought an awful lot about gangs and I began to see them in a very different way, as almost a biological formation. People make gangs—men and women, what have you. Cliques, clans, whatever you want to call it. There seems to be a big impulse there, something deeply social and political, but also maybe something biological.

I’d been thinking and meditating on this whole thing—this whole problem of the gang and what makes it. The interesting thing about gangs, as I wrote about them at that point in time, and as I mentioned, is that they had no economic basis. That all began to change during the period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially in relation to Vietnam, when more and more heroin began to be imported into the United States—a chunk of that coming through the good offices of the CIA. So, especially looking at the drug cartels in Mexico today, but also looking at this phenomenon of organized crime all over the world, the more you see that gangs are essentially capitalists. Within that system, they organize themselves: they have hierarchical principles and their leadership gets the best of everything. The lower strata are just the soldiers who risk their lives and don’t make out too well.

Look at the other gangs and mafia in ‘Ndrangheta, Calabria, the Camorra, the Japanese gangs, the Chinese triads, the Bulgarian gangs, the Russian gangs, all of that. It’s a business. Essentially, there are connections between these phenomena and corporate capitalism and politics, one way or another. On some level, there are always connections to something else—some other group, level, or economic phenomenon. In fact, no phenomenon, whether we’re talking physics or chemistry or what have you is totally isolated. Total isolation, or the making of discrete sets, is really an intellectual concept. No social formation is isolated in and of itself. It just isn’t.

What’s interesting is that, wherever you go, the gangs develop their own cultures. What makes them alike is generally their structures—their hierarchical structures—and the necessity for their leadership, whether it’s male or female, to exhibit charisma, machismo or machisma. And I don’t care whether you see this in corporations, which are supposedly rational entities but that, really, are not—because, otherwise, why would people talk about the “culture” of a corporation as something that can drive it into bankruptcy or make it successful? And how is that culture different from another corporation? So, in gangs and corporations both, we’re seeing a kind of driven necessity—maybe biological—to make and sustain a culture. But each culture is different.

Structurally, things look the same, but, culturally, things look different. That fascinates me.

Also, I grew up in a Communist household. Starting in the 1960s, I went back to reading Marx. In the back of my mind, though, there were aspects of Marx that seemed inadequate as a theory. It was very Western-centered; the number of classical and historical references in all of Marx’s work was just overwhelming to me. For all of his references, it felt limited. Then, as well, I began to think more in terms of neo-Darwinism. I don’t mean social Darwinism. Leftists and liberals deny the question of human nature, but what if it’s true? So that also became a consideration in my thinking—mixing the two: Marx and Darwin.

All of that was part of the back-story for The Warriors.

BLDGBLOG: Before we move on to other topics, I think it’s interesting how much the built landscape of New York has changed since you wrote The Warriors. I’m curious, if you were to update the story of Xenophon again and rewrite The Warriors today, if there is a different location you might choose, whether that’s a different city or a different part of New York.

Yurick: Well, I would make it global, for one thing. And I would try to bring into it questions of finance—things like that. I’m not sure, though; I haven’t thought of that. Yes, there was a political and economic connection to Xenophon, and to Xenophon’s story—essentially, these gang members were mercenaries, and they were also a surplus population pushed to the edge of society. They were, after all, kids. And they were revolutionaries, not just street criminals. But I don’t know exactly how I’d handle it today.

Again, the whole question of making a revolution in the old way—it’s a tricky one. From my way of thinking, what happened in the Russian Revolution is: you had an uprising. People were discontented and what have you. Then a moment of opportunity came along, when it was a complete breakdown, and, at that point, Lenin stepped in. It was purely opportunistic. There was nothing decent in his move. There it was. It happened. Boom. He took advantage.

BLDGBLOG: In your book-length essay Metatron: The Recording Angel, you combine so many of these interests—everything from finance to electronic writing, looking ahead to what we now call the internet, and so on. I’m curious if we could talk a little bit about how Metatron came about, what you were seeking to do with that book, and where you might take its research today?

Yurick: When I wrote that, it was still early on. Computers were not universally around. I had a friend who was a computer expert—he had become an expert in the 1950s—so I was introduced to computers and the idea long before there were PCs or anything like that. I knew, when I saw stuff that would later become the internet—exchanges between scientists who had access to this kind of stuff—I knew I was looking at a different world. I began to see signs that this was going to become a big phenomenon, one of information and the effects of information. And again, this was before anybody had home computers.

Then computers began to come in, bit by bit. We’re talking maybe 1979. What happened then was that I got tied up with an organization trying to promote the use of satellites for global education. By this time, though, having been through the 1960s and 70s, I was telling them that this was just not going to happen. You’re not going to get money for this kind of thing; they’re going to use satellites for any other purpose for the most part, maybe military purposes, maybe propagandistic purposes, certainly for telecommunications.

But I went down to Washington with these people a couple of times, and we sat in on the committee hearings. Then I wrote a piece—an essay—to sort of introduce our organization. I forget when it was—maybe 1979 or 1978—but Jimmy Carter was coming to the UN and, because of the connections of several people in this organization, somebody got my essay to Jimmy Carter’s people. He almost incorporated a piece of it into his speech at the UN!

That didn’t happen, of course, so I decided I would submit it to this little publishing house, and they asked me to expand on it. I did that, and that was Metatron.

So my mind was ranging over all these things. I was trying to think of what the effect was going to be of computers and networks and satellites, trying to anticipate a lot of side effects. There was a lot I didn’t foresee, but there were some things I saw beginning to happen—that then, in fact, did happen maybe ten years later. Things like running factory farm machines by satellite and, now, running drones over Afghanistan from a place in Nevada. Things like that.

Anyway, having been getting more and more involved in many areas, while at the same time trying to find a basis for writing my fiction from new perspectives, became very destabilizing. Because most writers—most people—just stop growing at a certain point. They stop taking in more stuff because it gets in the way of their writing. But the opposite was happening. For instance, with The Warriors, I was able to make an outline chart of how the themes would develop. I could coordinate everything: what happened to the clothing, what happened at a certain time of day, and so forth and so on. Interestingly, the form of the chart I borrowed from a business model called program evaluation. It was a review technique. So I could do this thing and it came easy.

But when I tried to do it with The Bag, it didn’t work. I had such a hard time doing The Bag. The chart began to expand and expand till it was about ten feet long; I had different colors on it; it just didn’t work right. But I was learning so much.

Anyway, at certain points you’ve got to say enough. I forget which writer said this: “You don’t finish the work you abandon.”

BLDGBLOG: The financial aspects of your work are very interesting here, as well.

Yurick: Do you mean the economic?

BLDGBLOG: Well, I mean “financial” more specifically to refer to the system of writings, agreements, valuations, and so forth that constitute the world of international finance—which, if you take a very basic, material view of things, is just people writing. It’s numbers and spreadsheets, stock prices, contracts, and slips of paper, licenses and patents—its own sort of literature. You imply as much, in Metatron, with its titular reference to the archangel of writing.

Yurick: OK, yes. You know, I’ve been saying for years to people that this is coming, this moment [the financial crisis of 2007-2009], and it’s happening now. I read the newspaper and I see it: these people manufacturing money out of their imaginations. Sooner or later the bubble has got to burst, and it’s bursting.

In a certain sense, what’s taken place—what’s taking place now—is a series of mistakes. In other words, you don’t hire the people who caused the problem in the first place to try to rectify it, yet that’s what’s happening. It’s very interesting, I think, to look at this in terms of the criminal elements that we discussed—the gangs—and to see that what they do is done through extortion, prostitution, the selling of illegal things, illegal commodities, and what have you. They accumulate money and they launder it. But this also happens at the very top levels of finance: they imagine money and then they objectify it in terms of mansions and things like that.

When you’re dealing with this kind of stuff, you’re dealing with fiction—and when you’re dealing with fiction, you’re in my realm.

BLDGBLOG: The financial world that’s been created in the last decade or so often just seems like a dream world of overlapping fictions—of Ponzi schemes and collateralized agreements that no one can follow. It’s as is people are just telling each other stories, but the characters are mutual funds, and, rather than words, they’re written in numbers. To paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke, it’s as if sufficiently advanced financial transactions have become indistinguishable from magic.

Yurick: A long time ago, I started to write a book in which I invented a planet, and the planet was ultimately nothing but finance. I called it Malaputa. Do you know Jonathan Swift’s work at all? One of the trips Gulliver takes is to an island called Laputa, which really means, in Latin, the whore or the hole. There he encounters nothing but intellectuals building the most astonishing mental structures and doing the stupidest things imaginable. Now, Malaputa would be the evil whore.

So the planet I began to invent was a world that interpenetrates ours and it works by the rules of our world, but it’s not visible. Ultimately, it resides in the financial system in which, as you get to the center of it, its mass and velocity keep on increasing potentially. It’s the movement, ultimately, of symbols.

I realized, at a certain point, that what I was also talking about was, in a sense, The Divine Comedy. The descent into the Inferno, if you remember, is in the form of a cone—the inside of a cone. The ascent to the top of Mount Purgatory is also a cone, but you climb on the outside. Then, to move on to heaven, you have a series of concentric circles, at the center of which is the ultimate paradise, which is where God resides. The circles are spinning, but they’re spinning in an odd way. If you’re at the center of a spinning circle, you’re barely moving around. If you’re on the outside, you’re moving with great velocity.

In this case, Dante tells us that the center of the circle spins with the greatest velocity, and the further out you get away from it, the slower it moves. What does finance have to do with this? The woman who Dante idolized—Beatrice—was a banker’s daughter. You could say his interest in her was partly financial, pursued through these circles and cones of symbols. Anyway, that’s the architecture of The Divine Comedy that I was getting at.

From this point—as all of this was going into the stuff I’m writing now—I began to meditate on the question of surplus labor value. Which, as Marx said, is the unpaid part of what a worker doesn’t get, the part that the owner—the owner of the means of production—expropriates.

BLDGBLOG: The Malaputa idea was for an entire standalone novel, or it’s something that you’re now including in your current work?

Yurick: It was originally going to be its own book, but I’m going to change that. I’ll incorporate it; I’ll reinvent it.

I wrote a piece a long time ago for—I forget the name of the magazine. It was on the question of the information revolution, the dimensions of which were not yet clear at that point. I think it was the mid-1980s. I was talking about, even at that point in time, the speed of the transactions, and the infinitesimally small space in which transactions occur—against the space that you have to traverse either by foot or other means, like to the market village or the shopping mall or the warehouse floor.

In other words, I’m saying that finance has a space—it has an architecture. You might want to transfer billions of dollars from one country to another, but both are accounts in one computer space. What you’re doing might have enormous effects on the real world—the world of humans and geography—but what you’ve done is move it a fraction of an inch, at an enormous speed, with an enormous velocity and mass. And that has real effects thousands of miles away.

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if you see other future developments of these works, or if there’s something new you’re working on at the moment.

Yurick: Yes—I’m working on two things that may intersect. One is a kind of biography that I call Revenge. What I realized, in a certain way—partly because I grew up in the Depression under bad circumstances, and now I see those same circumstances coming back again—I realized at a certain point that my novels Fertig and The Bag were revenge novels. That was a theme that was not clearly in my mind at the time, but that came into my consciousness relatively recently.

Revenge begins with trying to pick a starting point—to impose a starting point—because wherever you begin, there is no ultimate beginning. Someone did something to someone else, in reaction to something that came before that, and so on and so forth. You start in the middle of things, and choose a starting point. It’s like a lot of the things we say about The Iliad, for instance. They start in the middle of things, in medias res.

There was an essay I wrote for The Nation on Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, in which I panned the novel. But what I realized, even at the time I was writing it, was that, in a certain way, the story in that book—the true story it was based on—wasn’t just a random killing. It was a revenge killing. It was about two people who are, in a sense, dispossessed. But the person who got killed—not the family so much, but the farmer himself, Clutter—was no ordinary guy. He was no ordinary farmer, but a well-to-do guy with 3,000 acres and some cattle and maybe an oil-pumping system. He was important. He’d worked in government and he’d worked as a county agent. I won’t go into the history of the county agents and their ultimate role in making agribusiness as we know it today. But he was important enough in 1954 to have been interviewed about a kind of global crisis in agriculture in the magazine section of the New York Times.

This wasn’t the story Truman Capote told. Capote was given an assignment by the New Yorker and he went and he did it. He didn’t know or understand any of this background. He didn’t talk about the role of this guy. Not that this guy was the ultimate villain—this Clutter person—but, the fact is, he had a very key role. If he was important enough to be interviewed in a section on changes in agricultural policy in the New York Times Magazine, that means he’s not just nobody. The fact that he conjoined the outlaws, the killers—the fact that they conjoin, in a sense, with the Clutters—I think is a piece of, you can almost say, Dickensian chance. It’s like how some novelists will start out with two or three random incidents that are not connected at all and then mold them together.

I don’t know if you’ve read The Bridge of San Luis Rey? It’s about six or seven people who are on a bridge that collapses; it falls and they’re killed. What it is is an exercise in what brought these people together: what did they have, or not have, in common? Why this moment and not another moment? That’s what I wanted to develop with this, to go a little into the background of how I came to this line of thinking.

Now, one of the killers: his mother was an Indian [sic] and his father was a cowboy. The other one’s parents were poor farmers. So, here, we have three social groups expressed in these people. In the long struggle between corporate agriculture and the individual farmer, this is what develops: they get pushed off the land, these social groups. In fact, this also connects back to the old story of Joseph, in Egypt. With Joseph in Egypt, yes, he predicts the coming famine—the good times and the coming famine. But, when the famine does come, first he takes the farmer’s money, then he takes their land, and he moves them all into the cities. What you’ve got there is kind of an algorithm for the way agriculture develops: we’re talking Russia, the Soviet Union, China. We’re talking the United States. It looks different in different places, but the structure remains the same. You urbanize the people and you consolidate the land.

Then, of course, with the book I go into my own reactions to all kinds of literature, and I stop to try to rewrite that literature. For instance, suppose we think of The Iliad as one big trade war. Troy, as you know, sat on the route into the Black Sea, which means it commanded the whole hinterland where people like the Greeks and the Trojans did trading. The Trojan War was a trade war.

BLDGBLOG: The mergers and acquisitions of the ancient world.

Yurick: So that’s the kind of stuff I’m working on.

In the end, of course, the smaller farmer fought agribusiness tooth and nail, and they lost. We see what agribusiness has done to food itself, creating all kinds of mutational changes in seeds and so forth. Again, I think of the collectivization period in the Soviet Union in which, in order to win, you had to starve the peasants. That’s what the intellectuals of the time wanted, without understanding the practicality of life on the ground, so to speak. It was a catastrophe.

On the other hand, one of the images I had when I was a kid, during the Depression, was: you’d go see a newsreel and you’d see farmers spilling milk and grain on the ground because they couldn’t get their price. People didn’t have enough food, but they were just dumping their milk in the mud. These were smaller farmers—agribusiness hadn’t happened yet. So you’ve got two greed systems going on here.

Anyway, I use all that as the novel’s jumping-off point. In a sense, I’m saying Clutter had it coming to him—or his class had it coming to him.

But I’m in the very early stages. It becomes like a little race between living and doing it, and ultimately dying. I’m not rushing myself, but I’m having fun.

* * *

This interview was recorded in March 2009. Thank you to Sol Yurick for the conversation.

[Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté].

[Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté]. [Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté].

[Image: Flocking diagram by “Canadian Arctic sovereignty: Local intervention by flocking UAVs” by Gilles Labonté]. [Image: Robert Moses, via

[Image: Robert Moses, via  [Image: The same point in Shanghai, shifted between its map and satellite view; via Google Maps].

[Image: The same point in Shanghai, shifted between its map and satellite view; via Google Maps].

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via

[Image: Abandoned Packard plant in Detroit, via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Star trails, seen from space, via

[Image: Star trails, seen from space, via  [Image: More star trails from space, via

[Image: More star trails from space, via  [Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by  [Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.  [Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

Image from

Image from

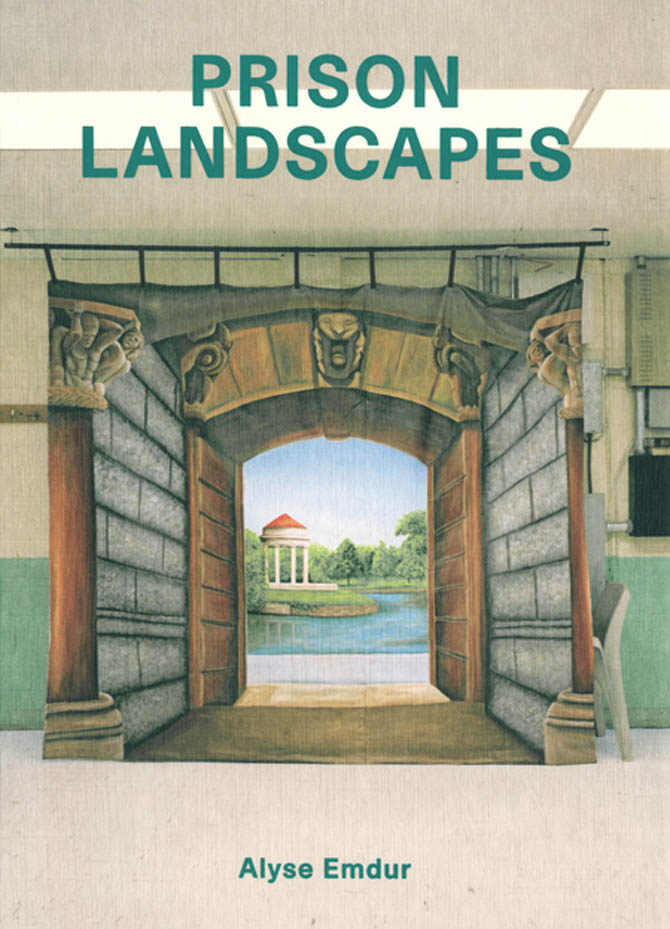

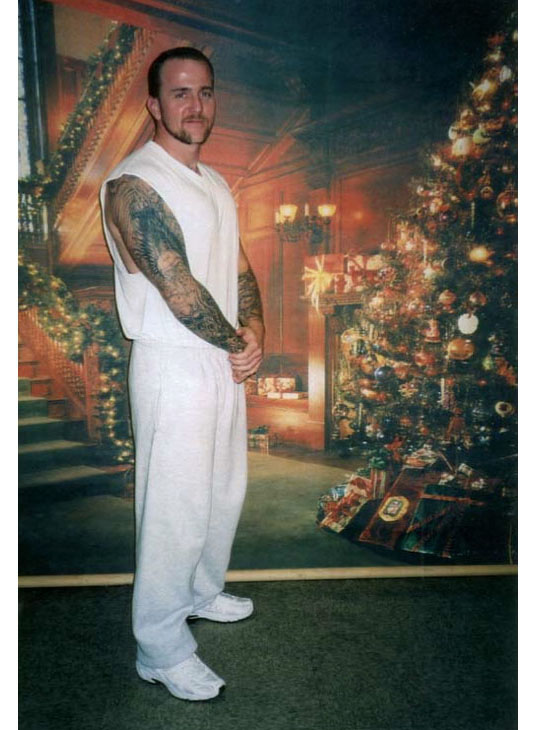

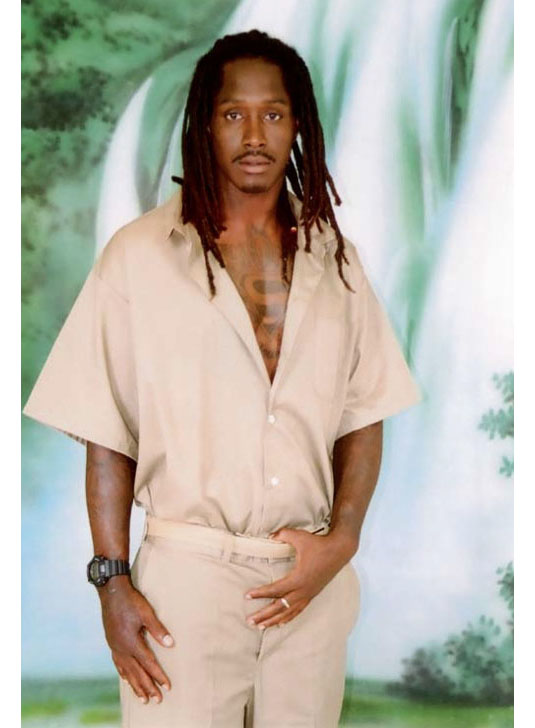

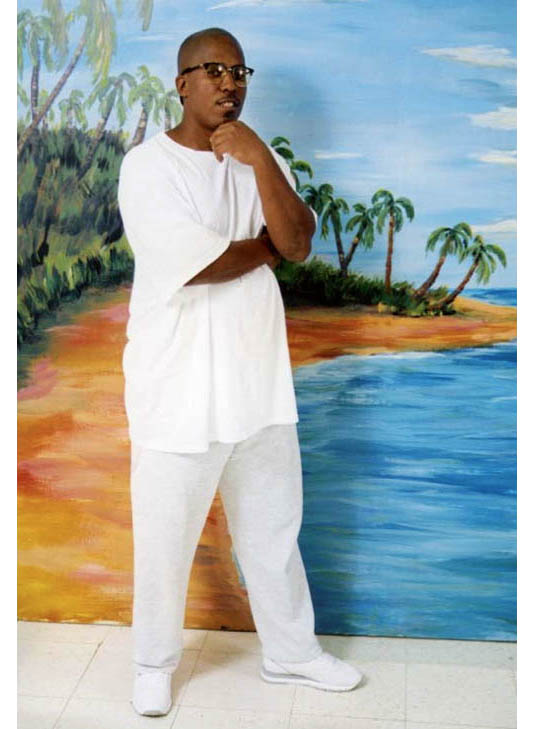

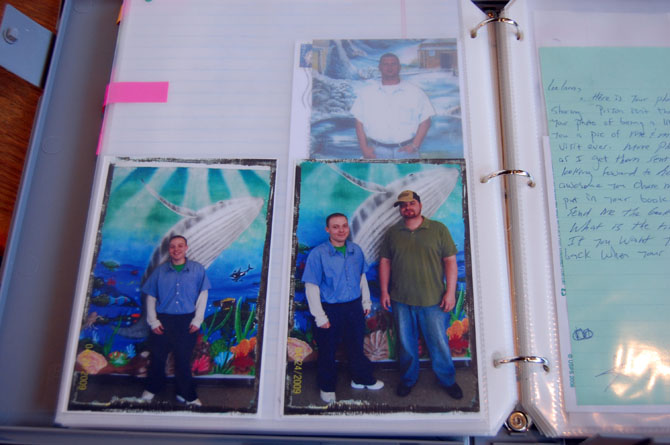

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by  [Image:

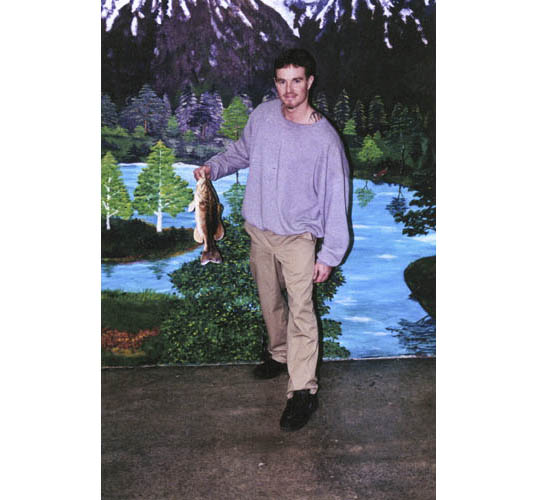

[Image:  [Image: James Bowlin, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy

[Image: James Bowlin, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy  [Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Shawangunk Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by

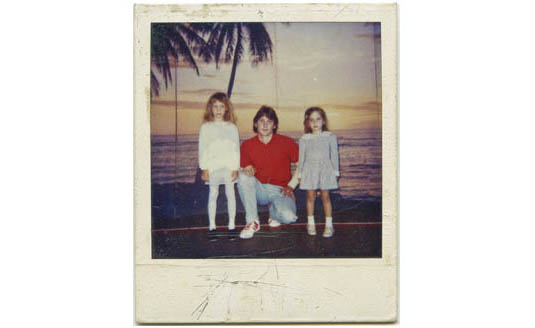

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Shawangunk Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by  [Image: Emdur family photo in front of prison visiting room backdrop; photograph courtesy

[Image: Emdur family photo in front of prison visiting room backdrop; photograph courtesy  [Image:

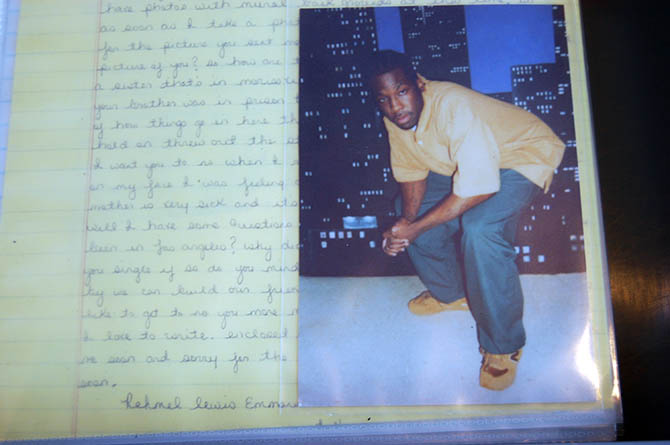

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Brandon Jones, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy

[Image: Brandon Jones, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy  [Image: Genesis Asiatic, Powhatan Correctional Center, Statefarm, Virginia; photograph courtesy

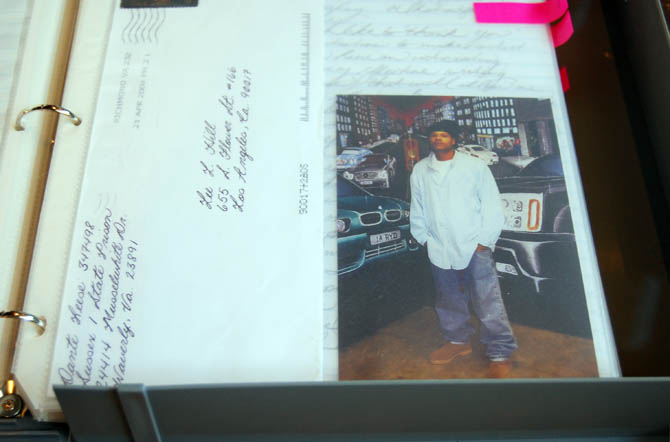

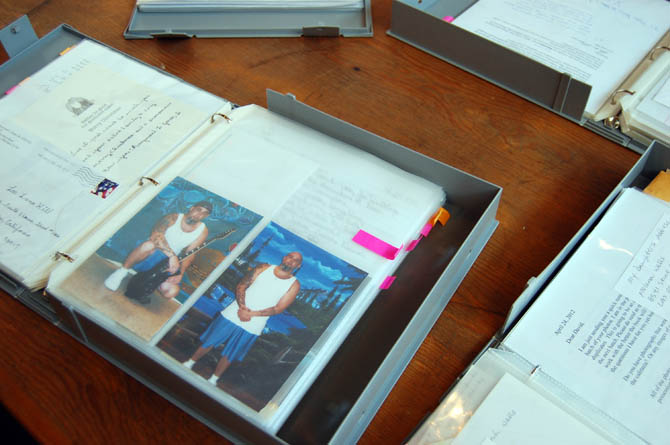

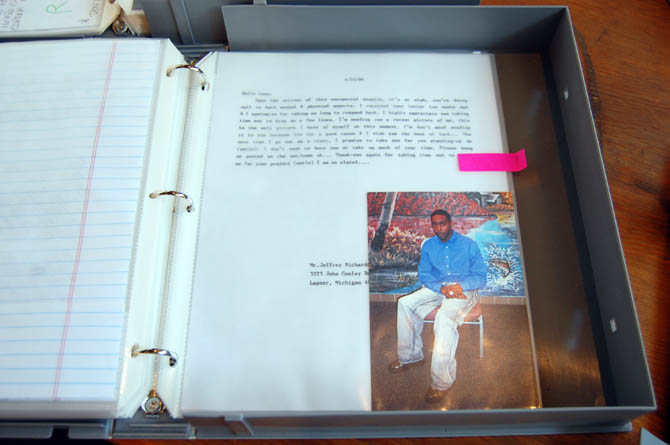

[Image: Genesis Asiatic, Powhatan Correctional Center, Statefarm, Virginia; photograph courtesy  One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to  [Image: Small prints of

[Image: Small prints of  [Image: Antoine Ealy, Federal Correctional Complex, Coleman, Florida; photograph courtesy

[Image: Antoine Ealy, Federal Correctional Complex, Coleman, Florida; photograph courtesy  [Image: Robert RuffBey, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, Georgia; photograph courtesy

[Image: Robert RuffBey, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, Georgia; photograph courtesy  [Image: One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

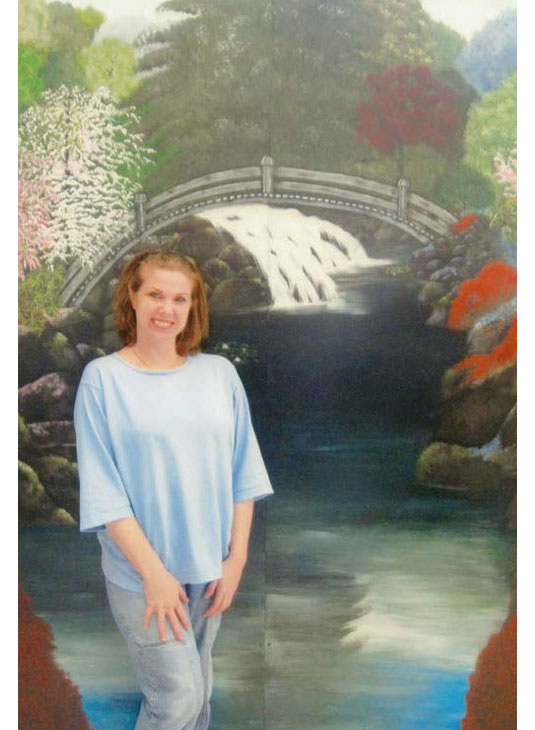

[Image: One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to  [Image: Kimberly Buntyn, Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California; photograph courtesy

[Image: Kimberly Buntyn, Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California; photograph courtesy

[Images: Sixteen binders’ worth of letters and prisoner portraits have been mailed to Emdur over the course of her project; photographs by

[Images: Sixteen binders’ worth of letters and prisoner portraits have been mailed to Emdur over the course of her project; photographs by  [Image: A binder of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

[Image: A binder of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to