[Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu].

[Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu].

Dr. Georges Benjamin is executive director of the American Public Health Association (APHA) and former Secretary of Maryland’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; there his responsibilities included updating the state’s quarantine laws in response to the threat of bio-terrorism. Dr. Benjamin is publisher of both the American Journal of Public Health and The Nation’s Health.

He is also co-editor, with Laura B. Sivitz and Kathleen Stratton, of the 2005 report Quarantine Stations at Ports of Entry: Protecting the Public’s Health. That report consists of more than 300 pages of policy guidelines for how the United States can operate, maintain, and even expand its network of national quarantine stations. The very idea of a national quarantine policy, let alone phrases like the international “Quarantine System,” can inspire, at the extreme, all manner of conspiracy-laden theories—including the specter of fully militarized, FEMA-administered concentration camps on U.S. soil. In reality, however, “today’s quarantine stations are not stations per se, but rather small groups of individuals located at major U.S. airports. Their core mission remains similar to that of old: mitigate the risks to residents of the United States posed by infectious diseases of public health significance originating abroad.”

A jurisdictional map of CDC quarantine stations is available online, complete with informational PDFs ready for download.

[Image: Map of the CDC’s U.S. quarantine stations].

[Image: Map of the CDC’s U.S. quarantine stations].

As part of our ongoing series of quarantine-themed interviews, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I spoke to Dr. Benjamin about the APHA’s policy recommendations for pandemic flu quarantine, about the role of eminent domain in the medically-motivated seizure of private property, and about the architectural challenge of designing dual-use facilities for public emergencies.

• • •Edible Geography: I was interested to read the American Public Health Association’s flu policy recommendations from 2007—in particular, to see the APHA’s emphasis on mental health support for people held in quarantine. What led to that being included in your official guidelines?

Dr. Georges Benjamin: If people are going to be confined for some time within a facility, then you want to make sure that you’re identifying those people who are already being treated for mental health issues. You want to make sure they’re getting their therapy and their medications, and you want to deal with any issue that might occur when someone has to stay alone under that level of stress.

Remember that someone who is quarantined is different from someone who is isolated. Quarantined people aren’t sick; they’re people who may get sick. They’re people who have been exposed to a disease but who are not physically ill. In many cases of voluntary quarantine, people are being asked to stay at home by themselves, or to stay self-isolated, and we need to make sure that someone is paying attention to them. We want to identify people who are not able to handle being by themselves or being in a relatively confined space—even if it’s inside their own home.

We were also concerned about making sure people have the basic needs of life: food, water, access to medical care, and access to social services. You want to make sure that you’ve addressed whatever those needs might be. All of these things were part of our package for people who might be quarantined.

BLDGBLOG: Who were the specific constituencies that called for those guidelines, and did anyone try to push you in another direction?

Dr. Benjamin: These guidelines come from our members. A lot of these discussions started way back when we were talking about smallpox, rather than pandemic influenza. We were thinking seriously about the idea of having people stay at home and be isolated, if they’re ill, or quarantined should there be a terrorist attack.

No one actually has access to smallpox now, but we were going out and vaccinating people against a potential terrorist threat, anyway. So we started having these discussions around the idea of whether or not you really needed to reinstitute large-scale—primarily voluntary—quarantine. In addition, we were talking about the risk of a pandemic.

Then, as you know, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. You had people there who, by virtue of the fact that they ended up in the Superdome, did not have all of the things they needed. Certainly a lot of that stuff had been planned for, but it hadn’t been done as robustly as it needed to have been—and, obviously, they had more people in there than they could take care of.

Our thinking, based on that experience in New Orleans, was: in an emergency situation, how do you make sure that people have what they need? And, quite frequently, the mental health needs of people are something that matters in every kind of large-scale public health emergency—whether that’s a tornado, a hurricane, the flu, or an event where large numbers of people have died. It’s one of those things that people don’t really think about ahead of time, unless you remind them to think about it.

Our recommendations don’t just apply, by the way, to the people who are confined; there are huge stresses on the people who are managing those events. The EMTs, the paramedics, and the public health personnel who are all actually managing things can be really challenged—and you have to pay attention to them, too.

[Image: Sample covers of the American Journal of Public Health; design by Kropf Design].

[Image: Sample covers of the American Journal of Public Health; design by Kropf Design].

BLDGBLOG: The APHA has also written about who exactly should have the authority to make decisions about who goes into quarantine and why. Can you talk us through your policy on that issue?

Dr. Benjamin: First of all, we try to guide by the least restrictive policy possible—and, to the extent that someone can be voluntarily in quarantine, that’s our first principle. Voluntary quarantine and the least restrictive quarantine possible is what we think is the most important way to start.

Simply giving people the facts about a disease process and keeping them well-educated and well-informed long before you’re going to need to take any action is the best policy. We, as an association, along with our colleagues in the federal agencies, have been trying to talk to the public about what the risks are for various diseases. How do you catch a disease—and how do you not catch it? How you protect yourself? How do you protect your loved ones? Usually, armed with this information, most people will follow the basic recommendations.

However, to the extent that you have to have compulsory quarantine—because you have someone who is continuing to put people at risk—then that is imposed, in the United States, by public health authorities. They have powers, mostly at the state and local level: those powers give them the authority to incentivize people not to put others—or themselves—at risk. In some cases, they can do that by having the police authorities act; in other cases, they have to go to court first. It depends on the individual jurisdiction.

In most cases, federal authorities’ powers end at the borders of the nation and then at the borders of each state. They can deal with issues across state lines, in some cases, and, of course, at our national borders and at ports of entry; but most of these quarantine authorities rest at the state and local health officer level.

BLDGBLOG: Has any of that legislation been revised in light of SARS, H1N1, or even the anthrax attacks?

Dr. Benjamin: There has been a national effort to modernize our public health laws. A lot of them were written years and years ago.

For instance, I was a state health official in Maryland from 1995 to 1999, and I was the secretary of health in Maryland from 1999 to 2002. During that time we began a process, which we finished when I was secretary, to update and modernize our laws. We had started talking about it before 9/11, but after 9/11 and the anthrax attacks , we realized that biological terrorism was a significant risk, and we really worked to strengthen the public health laws.

To give you an example of the kinds of changes and updates we made: we worked to put in some additional patient protections. The law at that time gave the health secretary enormous police powers to hold and to quarantine individuals—but there were no rights or rules for those individuals, or regulations about what they needed to receive while they were in confinement. The assumption was, of course, that they would get reasonable support and care—but we felt it was very important to guarantee that.

So we worked with several members of our advocacy community to strengthen the authority that the health officer had, and to make the authorities that I had at the time, as secretary of health, much clearer. But, on the same token, we were writing in protections. We guaranteed people due process. We guaranteed that, if we had to forcibly confine someone, then they would get medical care, social services, and social supports that they actually need. We put that in writing.

Other states around the nation have begun doing the same thing. There have been some public health law centers set up through various foundations, and they have also been working very hard to strengthen the various laws. There was a model public health law—I think it was produced with a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and several of the public health groups working with them. That law was then shared with all of the states and their elected officials, and it was used as a template through which states could look at their own laws and see how they matched up to the model.

Some states simply took the model and implemented it, exactly as it was written; some took pieces of it out; others took it and said, no, compared to the law we currently have, ours is better and we like ours. Either way, it served as a useful catalyst for people to begin looking at their own public health laws—not only in terms of the authorities that the public health officer had around isolation and quarantine, but also about reportable diseases, which diseases ought to be reported, and how, and who should do the reporting. There were also things that we added around patient protections, citizen protections, and due process. And there were sections that meant to clarify existing law, based on case law in the state, or nationally.

That work has been going on since late 2001, and it continues to this day in a variety of formats.

[Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the China Post].

[Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the China Post].

BLDGBLOG: In terms of these public health laws, where can quarantine occur? It was interesting during the SARS outbreak in Toronto, for instance, to see that hotel rooms were simply repurposed as temporary quarantine facilities.

Dr. Benjamin: Quarantine can occur anywhere—that’s the short answer.

Remember that quarantine is basically telling someone who has been exposed to a disease, even if they haven’t come down with that disease, to stay away from others, and to stay somewhere that we can observe them and see if they get sick. Functionally, that can occur anywhere—as long as you have the support that you need, and as long as you’re not kept somewhere where other people will be at risk. For someone who’s quarantined, a hospital is probably not a good place for them, because there are sick people in that hospital and, in any case, the hospital will usually need those beds.

Let’s say I travel to England for a business meeting, and there’s a big infectious disease outbreak. They’re not quite sure what it is, but I could theoretically have been exposed. They don’t want me to travel back home because they don’t want me on an airplane; I could expose people on that airplane. So they ask me to stay in my hotel room, and to get room service. That’s probably a perfectly reasonable request—as long as you know that, in everybody who’s had this disease, it shows up within 48-72 hours. It might be very inconvenient, but, in the interest of public health, somebody could ask me to do that. Now, there are issues around the air circulation in the hotel, and whether or not that’s appropriate—but let’s just assume that it is. From the APHA perspective, that request would be fine, particularly if you have somebody who can call and check on you a couple times a day and make sure that you’re not getting sick in the hotel room.

Now let’s say this happens at a wedding party taking place at a small hotel. For all practical purposes, if everybody at that hotel had been at the wedding, it would be reasonable to ask everybody to stay at that hotel—and, actually, they wouldn’t even have to stay in their rooms. They could be out and amongst each other, as long as they were fully informed about the symptoms that you get when you start to come down with whatever this disease process is. If those symptoms start to show, those people would then self-isolate, call public health authorities, and tell them, “I’m in my room, and I’ve got a cough and a fever, and I didn’t have that yesterday.”

If it turns out that this disease process is something mild, and we know you can take care of it there in the hotel room, then we’d probably just say, OK, isolate yourself in the hotel room. Before, you were able to get up and walk around the hotel—no big deal—but now you have to stay in your room. We’ll have the concierge send up your meals, and we’ll give you some Tylenol for your temperature. If it was something like H1N1—or some other viral illness that we knew is susceptible to antiviral agents—then we may very well give you antiviral agents, too. Of course, we’d also have the hotel doctor come up and see you. However, we would still ask you to stay in your room. That’s a voluntary isolation, now, within a quarantine facility, because you’ve been separated from everybody else.

The people who run the hotel, on the other hand, could say that they really don’t want this sick person staying in the hotel, for whatever reason. We’d then actually ask you to come out of the hotel; we’d come pick you up; and we’d take you to someplace else where people are being held and provided with medical care. At that point, you’re in isolation. It could be a hospital; it could be another facility. It could be a hotel; it could be a home. It could be anyplace where they’ve designated that as an isolation point. Again, in most cases it would be voluntary.

So it depends—these examples show that quarantine could take place anywhere, in a variety of forms.

[Images: (left) Reporter Will Weissert, quarantined in China, receives his lunch sealed in a plastic bag; (right) Weissert’s wife receives a medical check-up in the hotel room].

[Images: (left) Reporter Will Weissert, quarantined in China, receives his lunch sealed in a plastic bag; (right) Weissert’s wife receives a medical check-up in the hotel room].

BLDGBLOG: Things like eminent domain and the government seizure of private property—these legal issues surely play a role in quarantine guidelines?

Dr. Benjamin: You’re right—and we’ve had long discussions about those issues.

For example, let’s say we have to isolate people due to a very severe disease process. In most cases, when people are sick enough, they need to, and are willing to, go to a hospital—but one of the challenges we’ve found is that hospitals don’t want to be known as the “X-disease hospital”: the SARS hospital, the swine flu hospital, the smallpox hospital. There’s some history there—in the United States, it began with places that became known as tuberculosis sanatoriums. If the public begins to shun a place because they’re afraid of catching a disease that has somehow been associated with that hospital, then it takes that hospital out of business—even if you only have one or two cases.

We saw this during the anthrax attacks at hospitals where somebody had been exposed, in whatever way, to anthrax. Even though we know anthrax is not a contagious disease, we had patients who were very concerned—at OBGYN services, in particular. Pregnant women just wouldn’t go to that hospital. As it turns out, we only had a very few cases of anthrax, but the press got onto this, and they publicized the fact that a person with anthrax had been at this particular hospital. Then that hospital had patients who were concerned about going there. So, of course, what we had to do was get on TV ourselves and say: “No, no, you don’t need to worry about that. It’s not contagious. That’s not how you get anthrax. You can still go there; you can still deliver your baby there.” But reassuring the public is sometimes very difficult. In many cases, it’s more about fear than anything else.

The other piece of this is that, if you have a disease outbreak that is so widespread that you have lots of sick people, then it’s unlikely that you’ll have only one hospital impacted. One of the fallacies of people worrying about their hospital being the SARS hospital, or their hospital being the smallpox hospital, or the flu hospital, is that, in most cases, those diseases are so infectious that lots of cases are already in the hospital environment. They’re in the ER, in the outpatient clinics, etc. One hospital might have an intensive care unit, and the very sick patients may end up in that unit—but the other hospitals in the area will end up taking care of the outpatients. The likelihood of only one hospital being the hospital with a particular disease process, and being stigmatized because of that, is very low.

There are exceptions, of course: let’s say you’ve got a research hospital and it has a novel therapy, and the only way to get that novel therapy is by going there—well, that hospital is going to end up with a disproportionate number of those patients. That’s one of the communication issues that hospital is going to have to manage with the public.

Now, to your question, many of the public health laws do have statutes that allow for the taking of stuff. In Maryland, for example, the state can confiscate your facility—and it’s not just your facility: it could be your pharmaceuticals; it could be your box of syringes. If the state declares an emergency, and it has the authority of the law and it goes through the proper procedures, then, yes, it can confiscate things.

But what we did in Maryland was we clarified a few things: firstly, that you would be compensated. We thought that was very important to put in. We also wanted to make sure that it requires extraordinary efforts to make it happen. In Maryland, for instance, a disaster has to be declared by the governor, and there’s a legal process that one has to go through in order to confiscate someone’s stuff.

A lot of the plans in the U.S. for where we’ll put sick people raise some interesting issues. For example, some of these plans say that if we need to expand bed-space beyond the hospitals, then we need to use schools, gymnasiums—anyplace where you have a wide-open ward. Of course, there’s a big debate going on about whether those are the best places for these folks—and the reason for that debate is that they’re not built as health facilities. You couldn’t put your sickest people there. You might be able to quarantine people there—people who are well enough to get up and wash their hands and go to the bathroom, etc.—and you might be able to put people there who are moderately ill, but you couldn’t put very sick people there. It’s simply not set up as an intensive care unit.

The other thing to remember is that, even though you’ve got a disease outbreak going through your community, you still have the other, baseline disease processes. There are still heart attacks and strokes and people with seizures and kids with fever unrelated to the flu or unrelated to the infectious disease going on. You still need beds for people at ICUs for heart attacks, and you still have to treat cancer. The management challenge is to make sure that local providers don’t set up a process, of either isolation or quarantine, that deprives them of the resources they need to maintain their ongoing health system.

Edible Geography: Where are the gaps, as you see it, in public preparations for quarantine?

Dr. Benjamin: There are a couple of things I can think of right away. There’s the public education aspect that we and our colleagues are continuing to work on—there’s always more that could be done there.

The other thing is that we need buildings and facilities that have multiple uses. When you build hospital emergency rooms, for example—and it’s been fascinating watching this shift occur—we’ve gone from a situation where people had individual rooms in the ER to open-bed concepts. But what you need is flexibility. You need facilities flexible enough to accommodate multiple purposes.

You remember I talked about a gym being utilized as a potential quarantine spot? Well, some of the issues that get in the way of that are that there are not enough electrical outlets. You can’t bring up walls to partition the place in a way that easily allows you to isolate one group and quarantine another. There also isn’t the plumbing, and there probably aren’t enough bathrooms. You’ve put a lot of people together who may have a disease—and now you have a problem, because not everybody can wash their hands. We’re all using hand sanitizers today, and they’re wonderful, and they work; but, frankly, good old soap and hot water is the best thing to use.

Then again, most elementary schools were designed for little people, and now you’re about to put a bunch of adults in there; they might not have as many soap dispensers as you need, or the bathrooms are too large, or the toilets are too low, or there aren’t enough sinks. Or, again, maybe the sinks aren’t in the right place: they’re not by the bedside where infection-control needs to occur.

Building an environment that thinks about these other potential uses is extremely important, for places like hotels or gyms or the other big spaces that might be used to hold a bunch of people. And, by the way, quarantine is only one need for those things: as part of our overall public health preparedness, we have to look at putting people up because of a hurricane, or floods, or a tornado, or a big infectious outbreak.

The single-center principle means that a place needs to be flexible enough for large numbers of people, and in which you can have adequate infection-control, adequate toilet facilities, and adequate food facilities so that everyone can eat.

If we build places that do those kinds of things, then they’ll meet all the needs for isolation, all the needs for quarantine, and all the needs for housing people in an emergency.

[Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina].

[Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina].

BLDGBLOG: That actually reminds me of some stadiums in Japan that were built both as sports stadiums and as earthquake-disaster centers. There’s food and water stockpiled in the basement, the entryways are sized for emergency vehicles, and so on. How would you recommend this sort of architectural adaptation, on a policy level?

Dr. Benjamin: We wouldn’t have much trouble convincing the presidents of universities today, who are already challenged with a disease process big enough to affect the whole student body. In the United States right now, with H1N1, the number of sick kids is big enough that they’re having to manage those kids on campus. For a disease process in which people are going to be sick for five or seven days, it’s unrealistic to send them home once they’ve shown up on campus. Colleges are having to deal with accommodating them right now. You can bet that, at least on college campuses in the United States, they would be very sensitive to this idea of dual-use facilities, because there’s an operational need for it.

The second thing is, if I was trying to do this, I would be working directly with architects and engineers, convincing them of the need to do it and then letting them sell it. They can say how best to do this, in a way that does not obstruct the primary purpose of the facility. We don’t want to interrupt anyone’s football games, but at the moment, everyone says, yes, we can put people here but it’s only going to happen once or twice in my lifetime, when the truth is that, if you design it that way, then you could use it much more frequently for that purpose. You could get dual-use out of it. Getting the people who design these places to tell us how to do it, in an appropriate and cost-efficient manner, and then having them make the case to the owners and users, so that they know that this is value added to their facility: that’s how I would get this message across.

Then I would talk to elected city and state officials about ways they could leverage tax-payer dollars to get these dual-use facilities built. Let’s say I’m in city government and I have someone coming up to me wanting the city to put up tax-payer dollars to support the building of a football stadium or a basketball stadium or a new school. If I get this additional bonus—this dual-use that helps my emergency-preparedness—I’m more likely to want to use taxpayer dollars to support it. Increasingly, as you know, private sector guys are coming to the government and asking for fiscal support to build these facilities. If tax-payers are going to be paying for things, then the city or the community needs to get something out of it.

I can tell you that a lot of work had to be done to fix and clean the New Orleans Superdome—but if you had built it so that it could be much more functional in an emergency situation then you would have had less damage. And from an image perspective, a dual-use sports facility now has much more of a public value.

That’s my personal view, not the Association’s view; but I think it’s an effective argument.

• • •This autumn in New York City,

Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG have teamed up to lead an 8-week

design studio focusing on the spatial implications of quarantine; you can read more about it

here. For our studio participants, we have been assembling a coursepack full of original content and interviews—but we decided that we should make this material available to everyone so that even those people who are not in New York City, and not enrolled in the quarantine studio, can follow along, offer commentary, and even be inspired to pursue projects of their own.

For other interviews in our quarantine series, check out Extraordinary Engineering Controls: An Interview with Jonathan Richmond, On the Other Side of Arrival: An Interview with David Barnes, The Last Town on Earth: An Interview with Thomas Mullen, and Biology at the Border: An Interview with Alison Bashford.

More interviews are forthcoming.

[Image: Dressed in 21st-century personal protective equipment (PPE), I am standing next to Dr. Luigi Bertinato, wearing period plague doctor gear from the time of the Black Death, inside the library of the Querini Stampalia, Venice. Photo by Nicola Twilley.]

[Image: Dressed in 21st-century personal protective equipment (PPE), I am standing next to Dr. Luigi Bertinato, wearing period plague doctor gear from the time of the Black Death, inside the library of the Querini Stampalia, Venice. Photo by Nicola Twilley.] [Image: An arch inside the abandoned lazaretto, or quarantine hospital, on Manoel Island, Malta; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: An arch inside the abandoned lazaretto, or quarantine hospital, on Manoel Island, Malta; photo by Geoff Manaugh.] [Image: Inside the lazaretto at Ancona, Italy; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: Inside the lazaretto at Ancona, Italy; photo by Geoff Manaugh.] [Image: Nicola Twilley inside the high-level isolation unit’s Trexler Ebola system; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]

[Image: Nicola Twilley inside the high-level isolation unit’s Trexler Ebola system; photo by Geoff Manaugh.]  [Image: Walking inside the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a salt mine 2,150 feet below the surface of the Earth, where the United States is permanently burying nuclear waste; photo by Nicola Twilley.]

[Image: Walking inside the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a salt mine 2,150 feet below the surface of the Earth, where the United States is permanently burying nuclear waste; photo by Nicola Twilley.] [Image: Until Proven Safe, with a cover design by Alex Merto.]

[Image: Until Proven Safe, with a cover design by Alex Merto.]

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Liberian security forces implement “a quarantine of the West Point slum, stepping up the government’s fight to stop the outbreak and unnerving residents.” Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Neigborhood-scale quarantine; photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via

[Image: Enforcing quarantine; Photo by Abbas Dulleh/AP, via  [Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: A “quarantine house” in Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.  [Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.

[Image: Quarantine station, Pennsylvania; courtesy of the U.S.  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Images: Photos from previous

[Images: Photos from previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu].

[Image: An emergency hospital ward in Kansas during the 1918 flu]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sample covers of the

[Image: Sample covers of the  [Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the

[Images: Hong Kong’s entire Metro Park Hotel was put under quarantine for seven days after an H1N1-positive Mexican tourist stayed there in May 2009; “psychologists were on standby,” we read. All photos courtesy of the  [Images: (left) Reporter

[Images: (left) Reporter  [Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina].

[Images: Shuhei Endo’s “tennis dome/emergency center” (left), photographed by Kenichi Amano, next to the New Orleans Superdome, post-Katrina]. Camus’s novel—about a quarantined city in North Africa called Oran, where the bubonic plague has erupted, originating in rats that have come crawling out into the streets to die en masse—seems to illustrate quite well the proposition that fiction is an extraordinarily effective medium through which to describe architectural and urban experiences. One of Camus’s characters, for instance, surveys the quarantined city laid out before him: “At that moment he had a preternaturally vivid awareness of the town stretched out below, a victim world secluded and apart, and of the groans of agony stifled in its darkness.”

Camus’s novel—about a quarantined city in North Africa called Oran, where the bubonic plague has erupted, originating in rats that have come crawling out into the streets to die en masse—seems to illustrate quite well the proposition that fiction is an extraordinarily effective medium through which to describe architectural and urban experiences. One of Camus’s characters, for instance, surveys the quarantined city laid out before him: “At that moment he had a preternaturally vivid awareness of the town stretched out below, a victim world secluded and apart, and of the groans of agony stifled in its darkness.” [Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on

[Image: Quarantine facility and hospital ward on  [Image: U.S. “Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority,” updated January 18, 2005].

[Image: U.S. “Federal and State Isolation and Quarantine Authority,” updated January 18, 2005]. [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

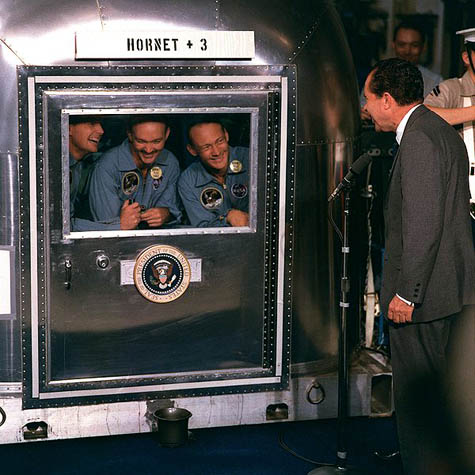

[Image:  [Image: President Nixon addresses

[Image: President Nixon addresses  [Image: “Fear of Flu” by

[Image: “Fear of Flu” by  [Image: Cages for the laboratory testing of rats and mice by

[Image: Cages for the laboratory testing of rats and mice by  [Image: A poster for

[Image: A poster for  [Image: Australian

[Image: Australian