[Image: Stephen Graham’s Cities Under Siege].

[Image: Stephen Graham’s Cities Under Siege].

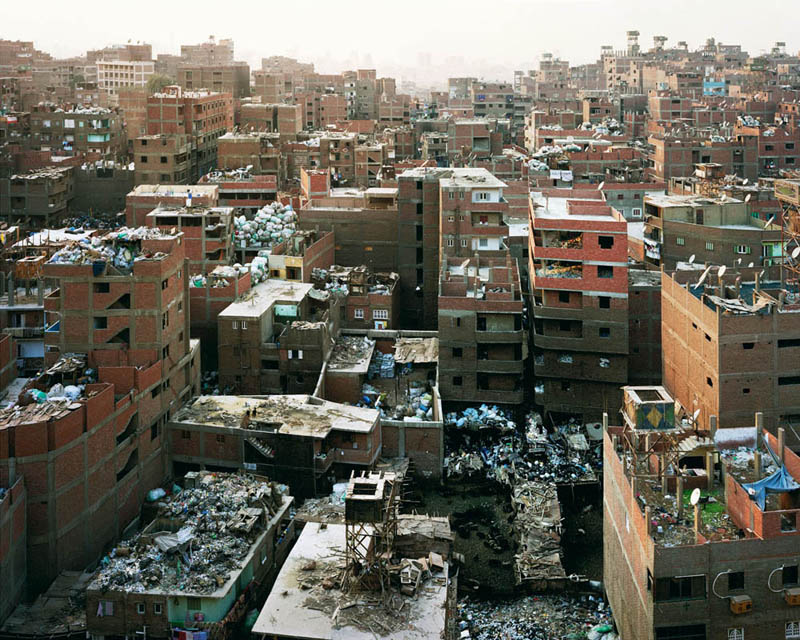

In a 2003 paper for the Naval War College Review, author Richard J. Norton defined the term feral cities. “Imagine a great metropolis covering hundreds of square miles,” Norton begins, as if narrating the start of a film pitch. “Once a vital component in a national economy, this sprawling urban environment is now a vast collection of blighted buildings, an immense petri dish of both ancient and new diseases, a territory where the rule of law has long been replaced by near anarchy in which the only security available is that which is attained through brute power.”

With the city’s infrastructure having collapsed long ago—or perhaps having never been built in the first place—there are no works of public sanitation, no sewers, no licensed doctors, no reliable food supply, no electricity. The feral city is a kind of return to medievalism, we might say, back to the future of a dark age for anyone but criminals, gangs, and urban warlords. It is a space of illiterate power—strength unresponsive to rationality or political debate.

From the perspective of a war planner or soldier, the feral city is also spatially impenetrable, a maze resistant to aerial mapping. Indeed, its “buildings, other structures, and subterranean spaces, would offer nearly perfect protection from overhead sensors, whether satellites or unmanned aerial vehicles,” Norton writes.

This is something Russell W. Glenn, formerly of the RAND Corporation—an Air Force think tank based in Southern California—calls “combat in Hell.” In his 1996 report of that name, Glenn pointed out that “urban terrain confronts military commanders with a synergism of difficulties rarely found in other environments,” many of which are technological. For instance, the effects of radio communications and global positioning systems can be radically limited by dense concentrations of architecture, turning what might otherwise be an exotic experience of pedestrian urbanism into a claustrophobic labyrinth inhabited by unseen enemy combatants.

Add to this the fact that military ground operations of the near future are more likely to unfold in places like Sadr City, Iraq—not in paragons of city planning like Vancouver—and you have an environment in which soldiers are as likely to die from tetanus, rabies, and wild dog attacks, Norton suggests, as from actual armed combat.

Put another way, as Mike Davis wrote in Planet of Slums, “the cities of the future, rather than being made out of glass and steel as envisioned by earlier generations of urbanists, are instead largely constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood. Instead of cities of light soaring toward heaven, much of the twenty-first-century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.”

But feral cities are one thing, cities under siege are something else.

[Images: The Fires by Joe Flood and Planet of Slums by Mike Davis].

[Images: The Fires by Joe Flood and Planet of Slums by Mike Davis].

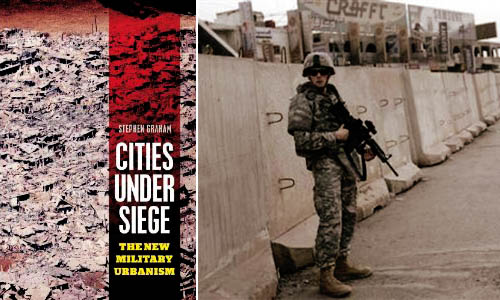

In his new book Cities Under Siege, published just two weeks ago, geographer Stephen Graham explores “the extension of military ideas of tracking, identification and targeting into the quotidian spaces and circulations of everyday life,” including “dramatic attempts to translate long-standing military dreams of high-tech omniscience and rationality into the governance of urban civil society.” This is just part of a “deepening crossover between urbanism and militarism,” one that will only become more pronounced, Graham fears, over time.

One particularly fascinating example of this encroachment of “military dreams… into the governance of urban civil society” is actually the subject of a forthcoming book by Joe Flood. The Fires tells the story of “an alluring proposal” offered by the RAND Corporation, back in 1968, “to a city on the brink of economic collapse [New York City]: using RAND’s computer models, which had been successfully implemented in high-level military operations, the city could save millions of dollars by establishing more efficient public services.” But all did not go as planned:

Over the next decade—a time New York City firefighters would refer to as “The War Years”—a series of fires swept through the South Bronx, the Lower East Side, Harlem, and Brooklyn, gutting whole neighborhoods, killing more than two thousand people and displacing hundreds of thousands. Conventional wisdom would blame arson, but these fires were the result of something altogether different: the intentional withdrawal of fire protection from the city’s poorest neighborhoods—all based on RAND’s computer modeling systems.

In any case, Graham’s interest is in the city as target, both of military operations and of political demonization. In other words, cities themselves are portrayed “as intrinsically threatening or problematic places,” Graham writes, and thus feared as sites of economic poverty, moral failure, sexual transgression, rampant criminality, and worse (something also addressed in detail by Steve Macek’s book Urban Nightmares). All cities, we are meant to believe, already exist in a state of marginal ferality. I’m reminded here of Frank Lloyd Wright’s oft-repeated remark that “the modern city is a place for banking and prostitution and very little else.”

In some of the book’s most interesting sections, Graham tracks the growth of urban surveillance and the global “homeland security market.” He points out that major urban events—like G8 conferences, the Olympics, and the World Cup, among many others—offer politically unique opportunities for the installation of advanced tracking, surveillance, and facial-recognition technologies. Deployed in the name of temporary security, however, these technologies are often left in place when the event is over: a kind of permanent crisis, in all but name, takes over the city, with remnant, military-grade surveillance technologies gazing down upon the streets (and embedded in the city’s telecommunications infrastructure). A moment of exception becomes the norm.

Graham outlines a number of dystopian scenarios here, including one in which “swarms of tiny, armed drones, equipped with advanced sensors and communicating with each other, will thus be deployed to loiter permanently above the streets, deserts, and highways” of cities around the world, moving us toward a future where “militarized techniques of tracking and targeting must permanently colonize the city landscape and the spaces of everyday life.”

In the process, any real distinction between a “homeland” and its “colonies” is irreparably blurred. Here, he quotes Michel Foucault: “A whole series of colonial models was brought back to the West, and the result was that the West could practice something resembling colonization, or an internal colonialism, on itself.” If it works in Baghdad, the assumption goes, then let’s try it out in Detroit.

This is just one of many “boomerang effects” from militarized urban experiments overseas, Graham writes.

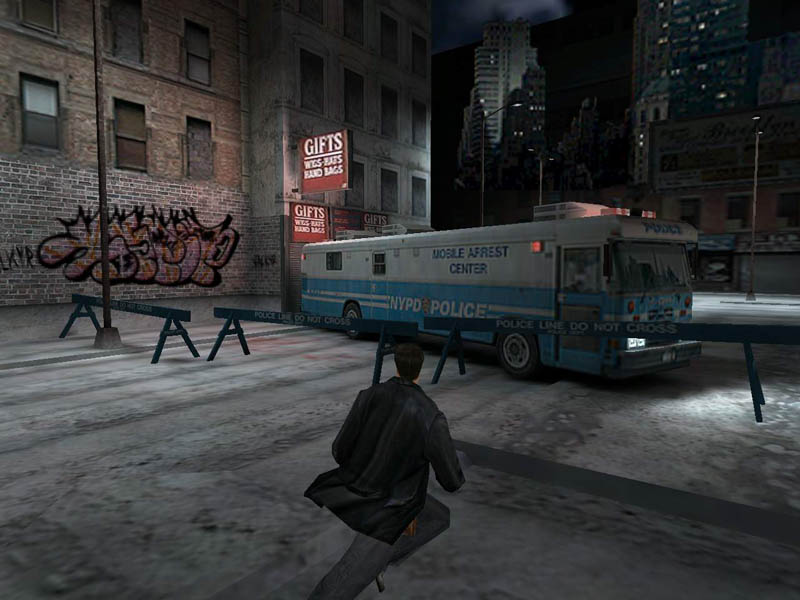

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

But what does this emerging city—this city under siege—actually look like? What is its architecture, its urban design, its local codes? What is its infrastructure?

Graham has many evocative answers for this. The city under siege is a place in which “hard, military-style borders, fences and checkpoints around defended enclaves and ‘security zones,’ superimposed on the wider and more open city, are proliferating.”

Jersey-barrier blast walls, identity checkpoints, computerized CCTV, biometric surveillance and military styles of access control protect archipelagos of fortified social, economic, political or military centers from an outside deemed unruly, impoverished and dangerous. In the most extreme examples, these encompass green zones, military prisons, ethnic and sectarian neighborhoods and military bases; they are growing around strategic financial districts, embassies, tourist and consumption spaces, airport and port complexes, sports arenas, gated communities and export processing zones.

Cities Under Siege also extensively covers urban warfare, a topic that intensely interests me. From Graham’s chapter “War Re-Enters the City”:

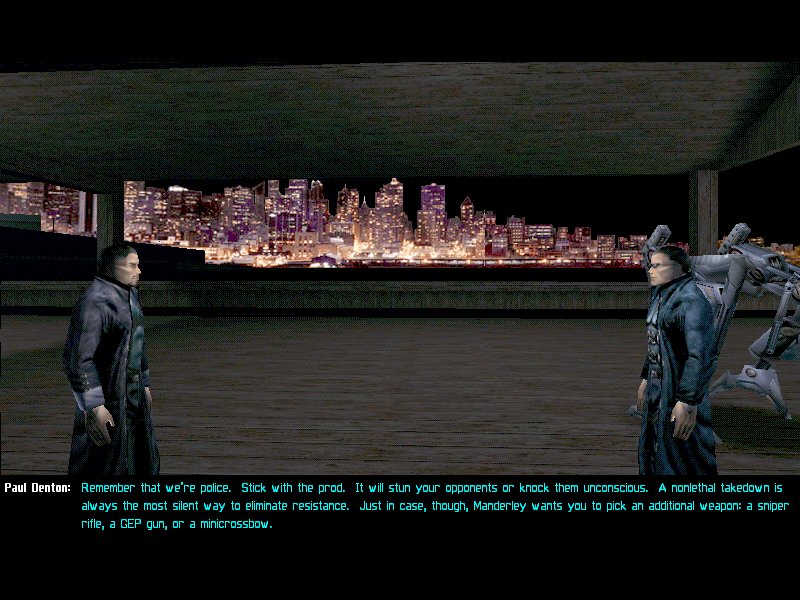

Indeed, almost unnoticed within “civil” urban social science, a shadow system of military urban research is rapidly being established, funded by Western military research budgets. As Keith Dickson, a US military theorist of urban warfare, puts it, the increasing perception within Western militaries is that “for Western military forces, asymmetric warfare in urban areas will be the greatest challenge of this century… The city will be the strategic high ground—whoever controls it will dictate the course of future events in the world.”

Ralph Peters phrased this perhaps most dramatically when he wrote, back in 1996 for the U.S. Army War College Quarterly, that “the future of warfare lies in the streets, sewers, high-rise buildings, industrial parks, and the sprawl of houses, shacks, and shelters that form the broken cities of our world.” The future of warfare, that is, lies in feral cities.

In this context, Graham catalogs the numerous ways in which “aggressive physical restructuring,” as well as “violent reorganization of the city,” is used, and has been used throughout history, as a means of securing and/or controlling a city’s population. At its most extreme, Graham calls this “place annihilation.” The architectural redesign of cities can thus be used as a military policing tactic as much as it can be discussed as a topic in academic planning debates. There are clearly echoes of Eyal Weizman in this.

On one level, these latter points are obvious: small infrastructural gestures, like public lighting, can transform alleyways from zones of impending crime to walkways safe for pedestrian use—and, in the process, expand political control and urban police presence into that terrain. But, as someone who does not want to be attacked in an alleyway any time soon, I find it very positive indeed when the cityscape around me becomes both safer by design and better policed. Equally obvious, though, when these sorts of interventions are scaled-up—from public lighting, say, to armed checkpoints in a militarized reorganization of the urban fabric—then something very drastic, and very wrong, is occurring in the city. Instead of a city simply with more cops (or fire departments), you begin a dark transition toward a “city under siege.”

I could go on at much greater length about all of this—but suffice it to say that Cities Under Siege covers a huge array of material, from the popularity of SUVs in cities to the blast-wall geographies of Baghdad, from ASBOs in London to drone helicopters in the skies above New York. Raytheon’s e-Borders program opens the book, and Graham closes it all with a discussion of “countergeographies.”

(Parts of this post, on feral cities, originally appeared in AD: Architectures of the Near Future, edited by Nic Clear).

[Image: “Angels” (2006) by Ruairi Glynn, one of the co-organizers of Stories of Change].

[Image: “Angels” (2006) by Ruairi Glynn, one of the co-organizers of Stories of Change]. 2) For its new call for papers, the Bauhaus-Universität’s Horizonte journal begins by quoting architect Raimund Abraham: “From earliest times,” Abraham writes, “architecture has complied with that order of logical forms which is contained in the nature of each material. That is to say: each material can only be used within the limits imposed by its organic and technical possibilities.” This fourth issue of the consistently well-designed journal explores the materiality of building: the issue thus “challenges the constraints and possibilities of architectural production, in order to reflect on the material and constructive methodologies of the present day.” I imagine essays and even speculative fiction covering everything from genetically engineered building materials to 3D printers—to new types of brick to artisanal craftwork—would be of interest. Your deadline is 8 July 2011.

2) For its new call for papers, the Bauhaus-Universität’s Horizonte journal begins by quoting architect Raimund Abraham: “From earliest times,” Abraham writes, “architecture has complied with that order of logical forms which is contained in the nature of each material. That is to say: each material can only be used within the limits imposed by its organic and technical possibilities.” This fourth issue of the consistently well-designed journal explores the materiality of building: the issue thus “challenges the constraints and possibilities of architectural production, in order to reflect on the material and constructive methodologies of the present day.” I imagine essays and even speculative fiction covering everything from genetically engineered building materials to 3D printers—to new types of brick to artisanal craftwork—would be of interest. Your deadline is 8 July 2011.  3) The Architectural League wants to give New York the Greatest Grid:

3) The Architectural League wants to give New York the Greatest Grid:  4) A new Advanced Architecture Contest has been announced, sponsored by the Institute for Advanced Architecture and Hewlett Packard. The theme this year is “CITY-SENSE: Shaping our environment with real-time data.” Aim to submit “a proposal capable of responding to emerging challenges in areas such as ecology, information technology, architecture, and urban planning, with the purpose of balancing the impact real-time data collection might have on sensor-driven cities.” Read more at the Advanced Architecture Contest website; the deadline is 26 September 2011.

4) A new Advanced Architecture Contest has been announced, sponsored by the Institute for Advanced Architecture and Hewlett Packard. The theme this year is “CITY-SENSE: Shaping our environment with real-time data.” Aim to submit “a proposal capable of responding to emerging challenges in areas such as ecology, information technology, architecture, and urban planning, with the purpose of balancing the impact real-time data collection might have on sensor-driven cities.” Read more at the Advanced Architecture Contest website; the deadline is 26 September 2011. 5) The California Architectural Foundation, in partnership with the Arid Lands Institute and the Academy for Emerging Professionals, has launched what it calls “an open ideas competition for retrofitting the American West.” The Drylands Competition seeks new ways of “anticipating, mitigating, and adapting to projected impacts of climate change” and other “critical challenges” facing the region. These challenges include water scarcity, obsolete infrastructure, and even the growing gap between scientific knowledge and public policy. “Design teams are invited to generate progressive proposals that suggest to policy makers and the public creative alternatives for the American west, ideas that may be replicated throughout the world.” Register by 15 November 2011; see their website for much more info.

5) The California Architectural Foundation, in partnership with the Arid Lands Institute and the Academy for Emerging Professionals, has launched what it calls “an open ideas competition for retrofitting the American West.” The Drylands Competition seeks new ways of “anticipating, mitigating, and adapting to projected impacts of climate change” and other “critical challenges” facing the region. These challenges include water scarcity, obsolete infrastructure, and even the growing gap between scientific knowledge and public policy. “Design teams are invited to generate progressive proposals that suggest to policy makers and the public creative alternatives for the American west, ideas that may be replicated throughout the world.” Register by 15 November 2011; see their website for much more info.

[Image: Photo by Allyn Baum for

[Image: Photo by Allyn Baum for  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: A “

[Image: A “

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

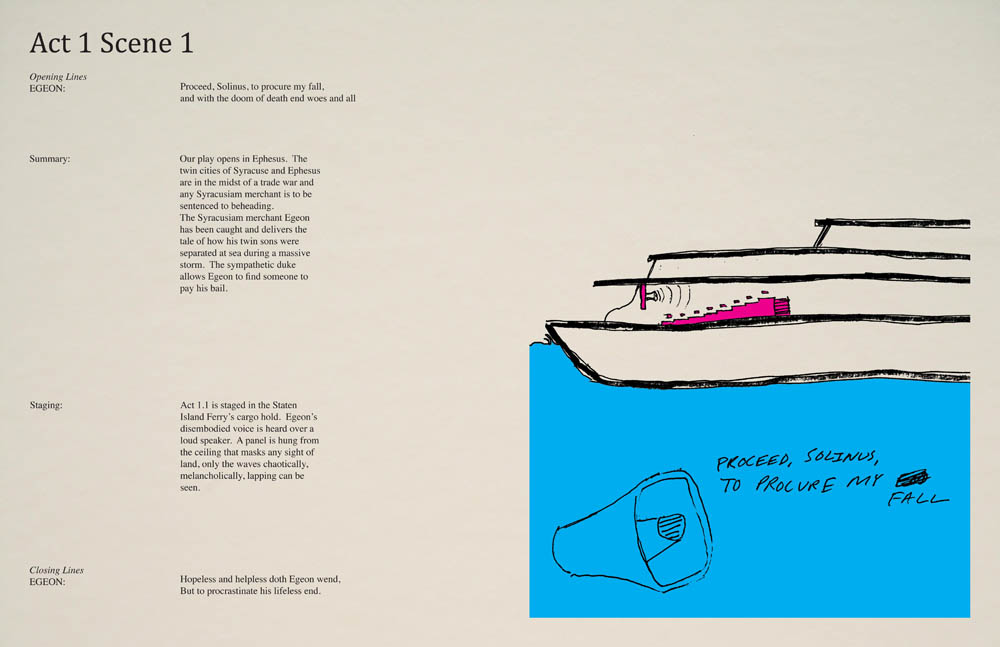

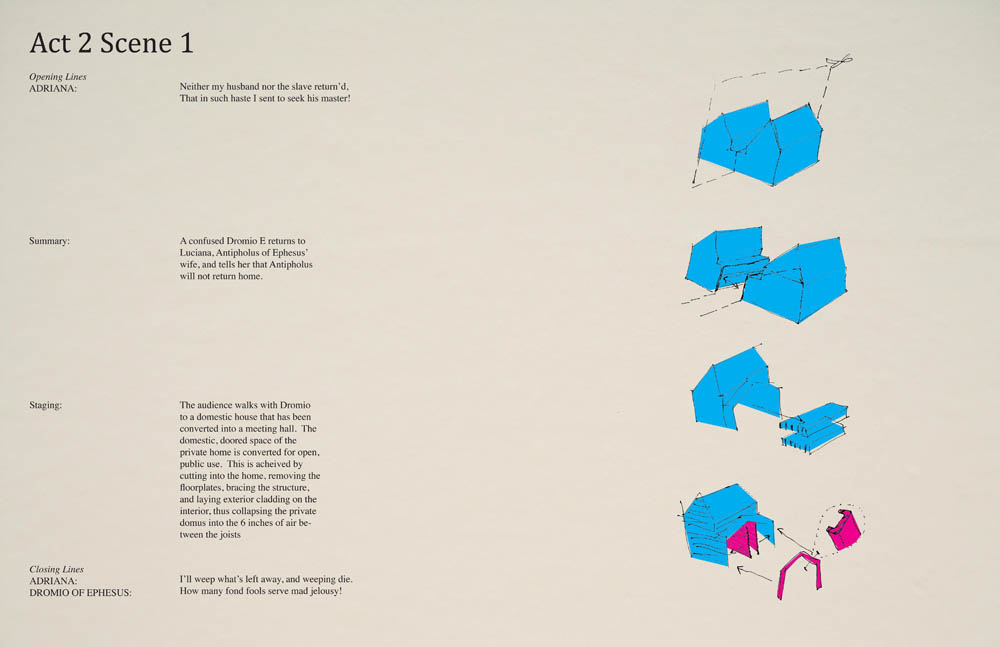

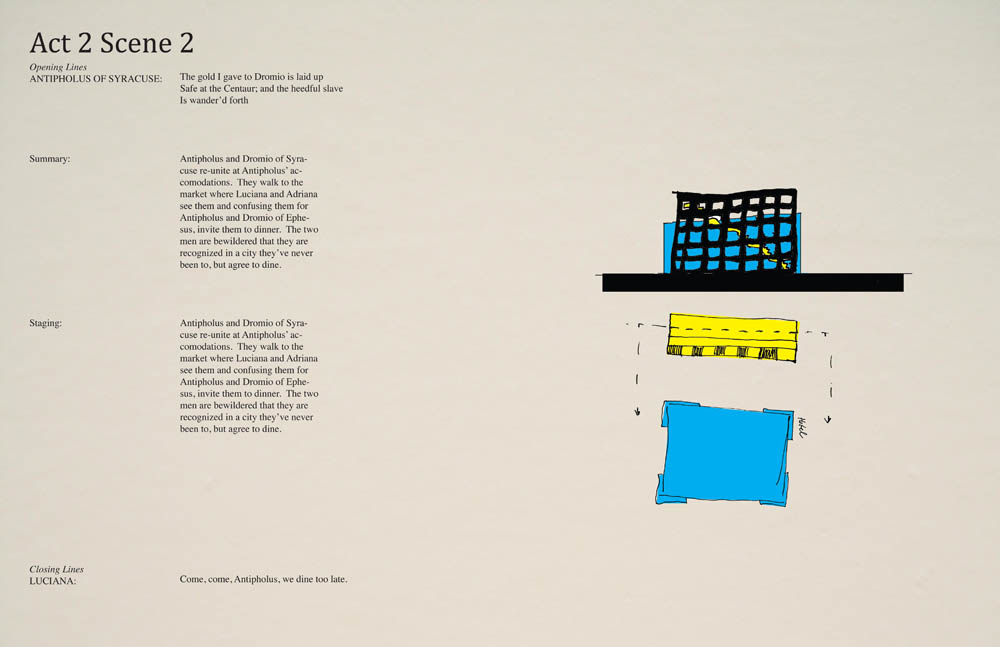

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Images:

[Images:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from

[Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from  [Image: An awesomely sinister photo from

[Image: An awesomely sinister photo from  [Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].  [Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

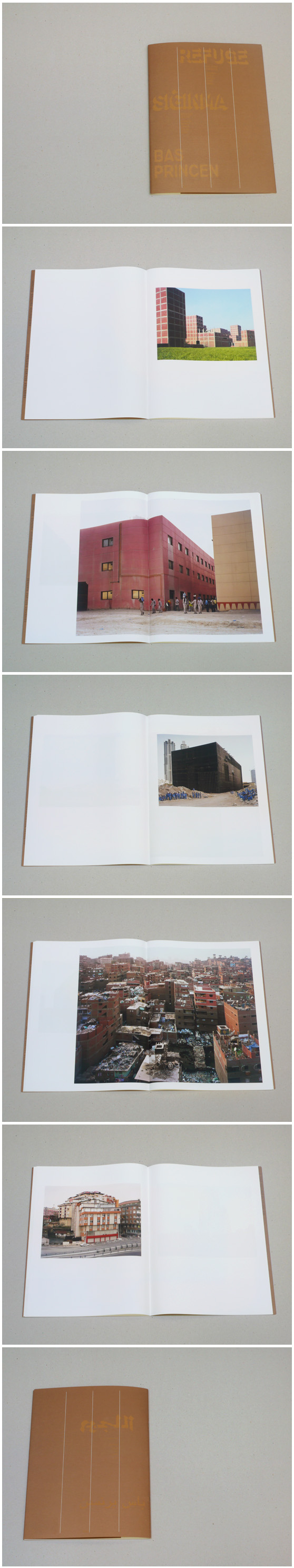

[Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: Spreads from “

[Images: Spreads from “ [Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “

[Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “ [Image: Stephen Graham’s

[Image: Stephen Graham’s  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq].

[Images: Blast walls in Iraq]. [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Stackin’ it at the

[Image: Stackin’ it at the  [Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at

[Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at