A rash of recent books about the geographic implications of climate change have crossed my desk. In this themed supplement to BLDGBLOG’s ongoing Books Received series, I thought I’d group them together into one related list.

[Image: Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal].

[Image: Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal].

What many of the books described in this post have in common—aside from their shared interest in what a climatically different earth will mean for the future of human civilization—is their use of short, fictionalized narratives set in specific future years or geographic regions as a way of illustrating larger points.

These narrative scenarios—diagnostic estimates of where we will be at some projected later date—come with chapter titles such as “Russia, 2019,” “China, 2042,” “Miami Beached,” and “Holland 2.0 Depolderized.” Among the various spatial and geopolitical side-effects of climate change outlined by these authors are a coming depopulation of the American Southwest; a massive demographic move north toward newly temperate Arctic settlements, economically spearheaded by the extraction industry and an invigorated global sea trade; border wars between an authoritarian Russia and a civil war-wracked China; and entire floating cities colonizing the waters of the north Atlantic as Holland aims to give up its terrestrial anchorage altogether, becoming truly a nation at sea.

“Will Manhattan Flood?” asks Matthew E. Kahn in his Climatopolis: How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future. What will Greenland look like in the year 2215, with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels at 1300 parts per million, according to Peter Ward’s The Flooded Earth: Our Future In a World Without Ice Caps? Will a “New North” rise as the Arctic de-ices and today’s economic powerhouses, from Los Angeles to Shanghai, stagnate under killer droughts, coastal floods, and heat waves, as Laurence C. Smith suggests in The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future?

[Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of Penn State].

[Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of Penn State].

However, climate change is only one of the world-altering forces under discussion in each of these six books. Demography, oil scarcity, natural resources, public hygiene, and accelerating globalization all play roles, to different extents, in these authors’ thinking. In one case, in particular—Float!: Building on Water to Combat Urban Congestion and Climate Change, the most practical book described here—new construction technologies, with immediate implications for architectural design, also take center stage.

In all cases, though, these books offer further evidence of an irresistible popular urge to discuss the future, and to do so through what can very broadly described as fiction. The recent speculative tone taken by much of today’s architecture writing is only part of this trend; from “design fiction” to speculative foreign policy blogs, and from “the world without us” to future food, a compulsion to understand what might happen to human civilization, in both the near and distant future, using fictional scenarios and speculative hypotheses seems to be at a high point of trans-disciplinary appeal.

As Heidi Cullen writes in The Weather of the Future: Heat Waves, Extreme Storms, and Other Scenes from a Climate-Changed Planet, there is something inherently difficult in comprehending the scale of climate change—what effects it might have, what systems it might interrupt or ruin. She thus imports lessons from cognitive psychology to understand what it is about climate change that keeps it so widely misinterpreted (though a hefty dose of media criticism, I’d argue, is far more apropos). It is interesting, then, in light of the apparent incomprehensibility of climate change, that fictional scenarios have become so popular a means of explaining and illustrating what Cullen calls our “climate-changed planet.”

This emerging narrative portraiture of climate change—exemplified by most of the books under discussion here, whether they present us with Atlanta running out of freshwater, frantic Chinese troops diverting rivers on the border with India, or a governmentally-abandoned Miami given over to anarchism and mass flooding—offers an imperfect but highly effective way of making a multi-dimensional problem understandable.

After all, if stories are an effective means of communicating culturally valuable information—if stories are pedagogically useful—then why not tell more stories about future climate change—indeed, why not tell more stories about architecture and buildings and emerging technologies and the spaces of tomorrow’s geopolitics?

Perhaps this is why so much of architecture writing today, both on blogs and elsewhere, so willfully crosses over into science fiction: if architecture literally is the design and proposal of a different world—one that might exist tomorrow, next year, next decade—then it is conceptually coextensive with the genre of scifi.

The current speculative turn in architecture writing is thus both unsurprising and highly appropriate to its subject matter—something worth bearing in mind by anyone hoping to find a larger audience for architectural critique.

[Image: “London as Venice” by Robert Graves and Didier Madoc-Jones, based on a photo by Jason Hawkes (part of an image series well-critiqued by the Guardian)].

[Image: “London as Venice” by Robert Graves and Didier Madoc-Jones, based on a photo by Jason Hawkes (part of an image series well-critiqued by the Guardian)].

An obvious problem with these preceding statements, however, is that we might quickly find ourselves relying on fiction to present scientific ideas to a popular audience; in turn, this risks producing a public educated not by scientists themselves but by misleading plotlines and useless blockbusters, such as The Day After Tomorrow and State of Fear, where incorrect popular representations of scientific data become mistaken for reports of verified fact.

In a way, one of the books cited in the following short list unwittingly demonstrates this very risk; Climate Wars: The Fight for Survival as the World Overheats would certainly work to stimulate a morally animated conversation with your friends over coffee or drinks, but there is something about its militarized fantasies of Arctic tent cities and Asian governments collapsing in civil free-fall that can’t help but come across as over-excitable, opening the door to disbelief for cynics and providing ammunition for extreme political views.

Indeed, I’d argue, the extent to which contemporary political fantasies are being narratively projected onto the looming world of runaway climate change has yet to be fully analyzed. For instance, climate change will cause the European Union to disband, we read in one book cited here, leaving Britain an agriculturally self-sufficient (though under-employed) island-state of dense, pedestrian-friendly urban cores; the U.S. will close its foreign military bases en masse, bringing its troops home to concentrate on large-scale infrastructural improvements, such as urban seawalls, as the middle class moves to high-altitude safety in the Rocky Mountains where it will live much closer to nature; Africa, already suffering from political corruption and epidemic disease, will fail entirely, undergoing a horrific population crash; and China will implode, leaving the global north in control of world resources once again.

It is important to note that all of these scenarios represent explicit political goals for different groups located at different points on the political spectrum. Perversely, disastrous climate change scenarios actually offer certain societal forces a sense of future relief—however misguided or short-term that relief may be.

Elsewhere, I’ve written about what I call climate change escapism—or liberation hydrology—which is the idea that climate change, and its attendant rewriting of the world’s geography through floods, is being turned into a kind of one-stop shop, like the 2012 Mayan apocalypse, for people who long for radical escape from today’s terrestrial status quo but who can find no effective political means for rallying those they see as forming a united constituency. Climate change thus becomes a kind of a deus ex machina—a light at the end of the tunnel for those who hope to see the world stood abruptly on its head.

Indeed, we might ask here: what do we want from climate change? What world do we secretly hope climate change will create—and what details of this world can we glimpse in today’s speculative descriptions of the future? What explicit moral lessons do we hope climate change will teach our fellow human beings?

[Image: “London-on-Sea” by Practical Action].

[Image: “London-on-Sea” by Practical Action].

Of course, the six books listed below are by no means the only ones worth reading on these topics; in fact, the emerging genre of what I’ll call climate futures is an absolutely fascinating one, and these books should be seen as a useful starting place. I would add, for instance, that Charles Emmerson’s recent Future History of the Arctic clearly belongs on this list—however, I covered it in an earlier installment of Books Received. Further, Forecast: The Consequences of Climate Change, from the Amazon to the Arctic, from Darfur to Napa Valley by Stephan Faris is a commendably concise and highly readable introduction to what global climate change might bring, and Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change has become something of a minor classic in this emerging field.

So, without further ado, here are six new books about climate futures.

—The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future by Laurence C. Smith (Dutton). Smith’s book is a virtuoso example of what I would call political science fiction, extrapolating from existing trends in demography, natural-resource depletion, globalization, and climate change to see what will happen to the eight nations of the Arctic Rim—what Smith alternately calls the New North and the Northern Rim. “I loosely define this ‘New North,'” Smith writes, “as all land and oceans lying 45º N latitude or higher currently held by the United States, Canada, Iceland, Greenland (Denmark), Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.”

—The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future by Laurence C. Smith (Dutton). Smith’s book is a virtuoso example of what I would call political science fiction, extrapolating from existing trends in demography, natural-resource depletion, globalization, and climate change to see what will happen to the eight nations of the Arctic Rim—what Smith alternately calls the New North and the Northern Rim. “I loosely define this ‘New North,'” Smith writes, “as all land and oceans lying 45º N latitude or higher currently held by the United States, Canada, Iceland, Greenland (Denmark), Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.”

I should point out that the book’s cover art depicts downtown Los Angeles being over-run by the cracked earth of a featureless desert, as clear an indication as any that Smith’s New North will benefit from negative—indeed, sometimes catastrophic—effects elsewhere.

In an article-slash-book-excerpt published last month in the Wall Street Journal, Smith wrote: “Imagine the Arctic in 2050 as a frigid version of Nevada—an empty landscape dotted with gleaming boom towns. Gas pipelines fan across the tundra, fueling fast-growing cities to the south like Calgary and Moscow, the coveted destinations for millions of global immigrants. It’s a busy web for global commerce, as the world’s ships advance each summer as the seasonal sea ice retreats, or even briefly disappears.” Further:

If Florida coasts become uninsurable and California enters a long-term drought, might people consider moving to Minnesota or Alberta? Will Spaniards eye Sweden? Might Russia one day, its population falling and needful of immigrants, decide a smarter alternative to resurrecting old Soviet plans for a 1,600-mile Siberia-Aral canal is to simply invite former Kazakh and Uzbek cotton farmers to abandon their dusty fields and resettle Siberia, to work in the gas fields?

Being an unapologetic fan of rhetorical questions—will speculative Arctic infrastructure projects be, in the early 2010s, what floating architecture was to the mid-2000s?—the overall approach of Smith’s book maintains a strong appeal for me throughout. The final chapter, in which, as Smith writes, we “step out of the comfort zone” into more open speculation, caps the book off nicely.

—The Flooded Earth: Our Future In a World Without Ice Caps by Peter D. Ward (Basic Books). Ward, a paleontologist, has produced a disturbing overview of how terrestrial ecosystems might be fundamentally changed as sea levels rise—and rise, and rise. Ward has the benefit of calling upon data taken from extremely distant phases of the earth’s history, almost all of which becomes highly alarming when transposed to the present and near-future earth. “This book is based on the fact that the earth has flooded before,” he writes, including phases in which seas rose globally at rates of up to 15 feet per century.

Ward successfully communicates the fact that the stakes of climate change are urgent and huge. Indeed, he writes, “The most extreme estimate suggests that within the next century we will reach the level [of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere] that existed in the Eocene Epoch of about 55 million to 34 million years ago, when carbon dioxide was about 800 to 1,000 ppm. This might be the last stop before a chain of mechanisms leads to wholesale oceanic changes that are not good for oxygen-loving life.” That is, a cascade of terrestrial side-effects and uncontrollable feedback loops could very well begin, ultimately extinguishing all oxygen-breathing organisms and kickstarting a new phase of life on earth. Whatever those future creatures might be, they will live, as Ward has written in another book, under the specter of a “green sky.” Brief fictional scenarios—including future bands of human “breeding pairs” wandering through flooded landscapes—pepper Ward’s book.

—The Weather of the Future: Heat Waves, Extreme Storms, and Other Scenes from a Climate-Changed Planet by Heidi Cullen (Harper). Cullen’s book is the one title listed here with which I am least familiar, having read only the opening chapter. But it, too, is organized by region and time frame: the Great Barrier Reef, California’s Central Valley, the Sahel in Africa, Bangladesh, New York City, and so on. The shared references to these and other locations in almost all contemporary books on climate change suggests an emerging geography of hotspots—a kind of climate change tourism in which authors visit locations of projected extreme weather events before those storms arrive. Cullen’s book “re-frightened” Stephen Colbert, for whatever that’s worth; I only wish I had had more time to read it before assembling this list.

—Float!: Building on Water to Combat Urban Congestion and Climate Change by Koen Olthuis and David Keuning (Frame). When David Keuning sent me a review copy of this book he joked that “offshore architecture has been relatively depleted of its novelty over the last few years”—an accurate statement, as images of floating buildings bring back strong memories of the architectural blogosphere circa 2005.

—Float!: Building on Water to Combat Urban Congestion and Climate Change by Koen Olthuis and David Keuning (Frame). When David Keuning sent me a review copy of this book he joked that “offshore architecture has been relatively depleted of its novelty over the last few years”—an accurate statement, as images of floating buildings bring back strong memories of the architectural blogosphere circa 2005.

However, Keuning and Olthuis needn’t be worried about depleting the reader’s interest. A remarkably stimulating read, Float! falls somewhere between design textbook, aquatic manifesto, and environmental exhortation to explore architecture’s offshore future. Water-based urban redesign; public transportation over aquatic roadways; floating barge-farms (as well as floating prisons); maneuverable bridges; entire artificial archipelagoes: none of these are new ideas, but seeing them all in one place, in a crisply designed hardback, is an undeniable pleasure.

The book is occasionally hamstrung by its own optimism, claiming, for instance, that “Once a floating building has left its location, there will be nothing left to remind people of its former presence,” an environmentally ambitious goal, to be sure, but, without a clear focus on maritime waste management (from sewage to rubbish to excess fuel) such statements simply seem self-congratulatory. Having said that, Float! is an excellent resource for any design studio or seminar looking at the future of floating structures in an age of flooding cities.

—Climatopolis: How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future by Matthew E. Kahn (Basic Books). Kahn’s book is at once hopeful—that cities will energetically reconfigure themselves to function smoothly in a decarbonized global economy—and cautionary, warning that whole regions of the world might soon become uninhabitable.

Kahn’s early distinction between New York City and Salt Lake City—the former considered high-risk, due to coastal flooding and extreme weather events, the latter an example of what Kahn calls “safe cities”—is useful for understanding the overall, somewhat armchair tone of the book. Climatopolis is not hugely rigorous in its exploration of what makes a city “climate-safe,” and it overestimates the descriptive value of using “Al Gore” as a personality type, seeming to cite the politician at least once every few pages, but if your interests are more Planetizen than Popular Science, this is a useful overview of the urban effects of climate change over disparate cities and regions.

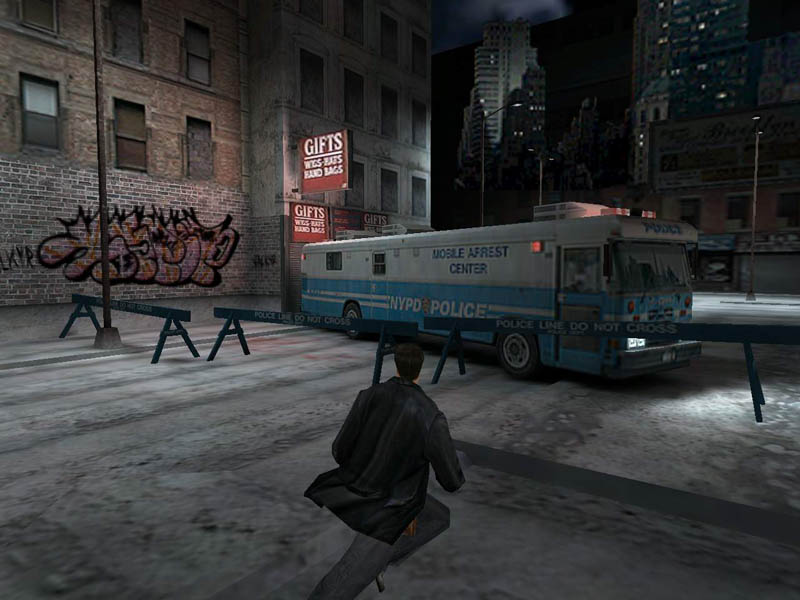

—Climate Wars: The Fight for Survival as the World Overheats by Gwynne Dyer (Oneworld Publications). Dyer writes that his awareness of climate change was kicked off by two things: “One was the realization that the first and most important impact of climate change on human civilization will be an acute and permanent crisis of food supply.” The other “was a dawning awareness that, in a number of the great powers, climate-change scenarios are already playing a large and increasing role in the military planning process.” Putting two and two together, Dyer has hypothesized, based on a close reading of military documents outlining climate-change contingency plans, what he calls climate wars: wars over food, water, territory, and unrealistic lifestyle guarantees.

Dyer’s book utilizes the most explicitly fictionalized approach of all the books under discussion here—to the extent that I would perhaps have urged him literally to write a novel—and he is very quick to admit that the outcome of his various, geographically widespread scenarios often contradict one another. For those of you with a taste for the apocalypse, or at least a voyeuristic interest in extreme survivalism, this is a good one. For those of you not looking for what is effectively a military-themed science fiction novel in journalistic form, you would do better with one of the titles listed above.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

[Image: The electromagnetic infrastructure of Los Angeles; photo by the

[Image: The electromagnetic infrastructure of Los Angeles; photo by the  [Image: “Topping-out ceremony” at the Onkalo nuclear-waste sequestration site, Finland; photo by

[Image: “Topping-out ceremony” at the Onkalo nuclear-waste sequestration site, Finland; photo by

[Image: An otherwise unrelated temple complex in Indonesia].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated temple complex in Indonesia].

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of

[Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ —

— —

—

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: The yellow chipboards of the

[Image: The yellow chipboards of the  [Image: Assembly robots by

[Image: Assembly robots by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: A “

[Image: A “

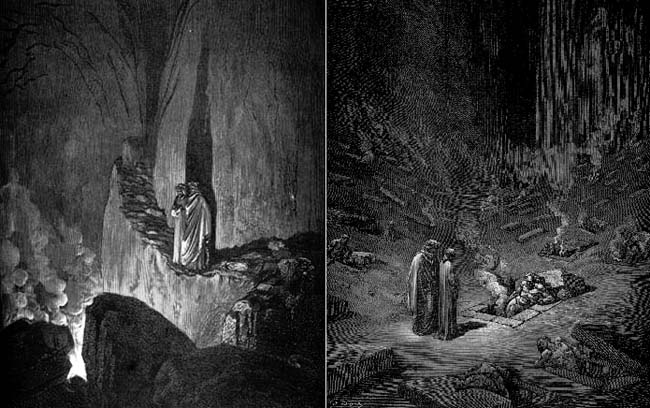

[Images: Two illustrations for Dante’s

[Images: Two illustrations for Dante’s

[Image: Viewmaster images of the

[Image: Viewmaster images of the  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The way out.

[Image: The way out.

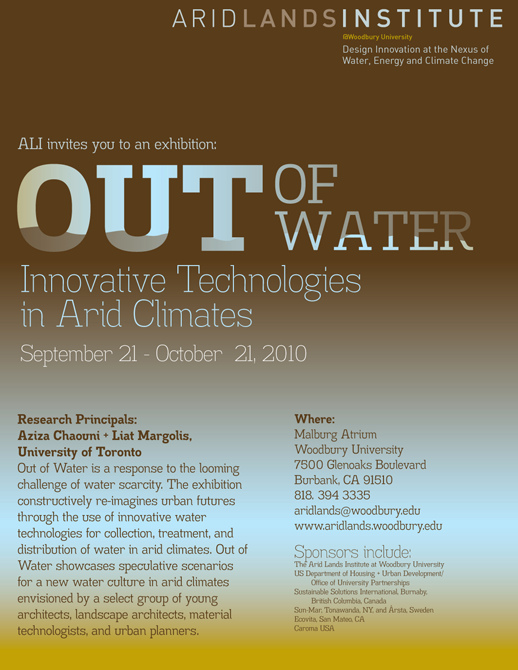

If I could go back in time, there are two things I would have prioritized this autumn, had I known about them earlier: 1) I would have stopped by the

If I could go back in time, there are two things I would have prioritized this autumn, had I known about them earlier: 1) I would have stopped by the  Here’s a description of the lecture series:

Here’s a description of the lecture series:

The specific lectures sound almost too good to be true, including a forthcoming talk this Thursday, November 18, about the stepwells of India—fantastically gorgeous native hydrological structures I’ve returned to again and again in my own off-blog reading and research.

The specific lectures sound almost too good to be true, including a forthcoming talk this Thursday, November 18, about the stepwells of India—fantastically gorgeous native hydrological structures I’ve returned to again and again in my own off-blog reading and research.  [Image: Stepwell at Chand Baori, courtesy of

[Image: Stepwell at Chand Baori, courtesy of