[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by Rodney Fitch, whose later motto was “Shopping is the Purpose of Life.” I don’t otherwise have any info about the school; image found via aqqindex].

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by Rodney Fitch, whose later motto was “Shopping is the Purpose of Life.” I don’t otherwise have any info about the school; image found via aqqindex].

Tag: Architecture

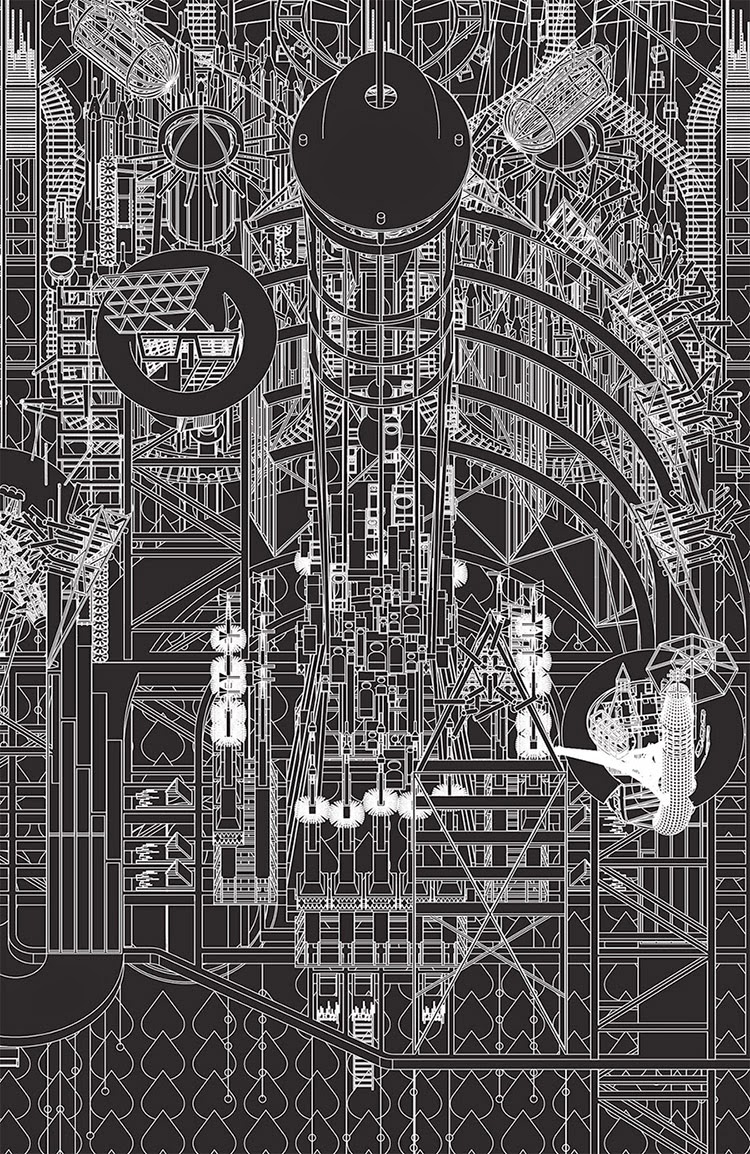

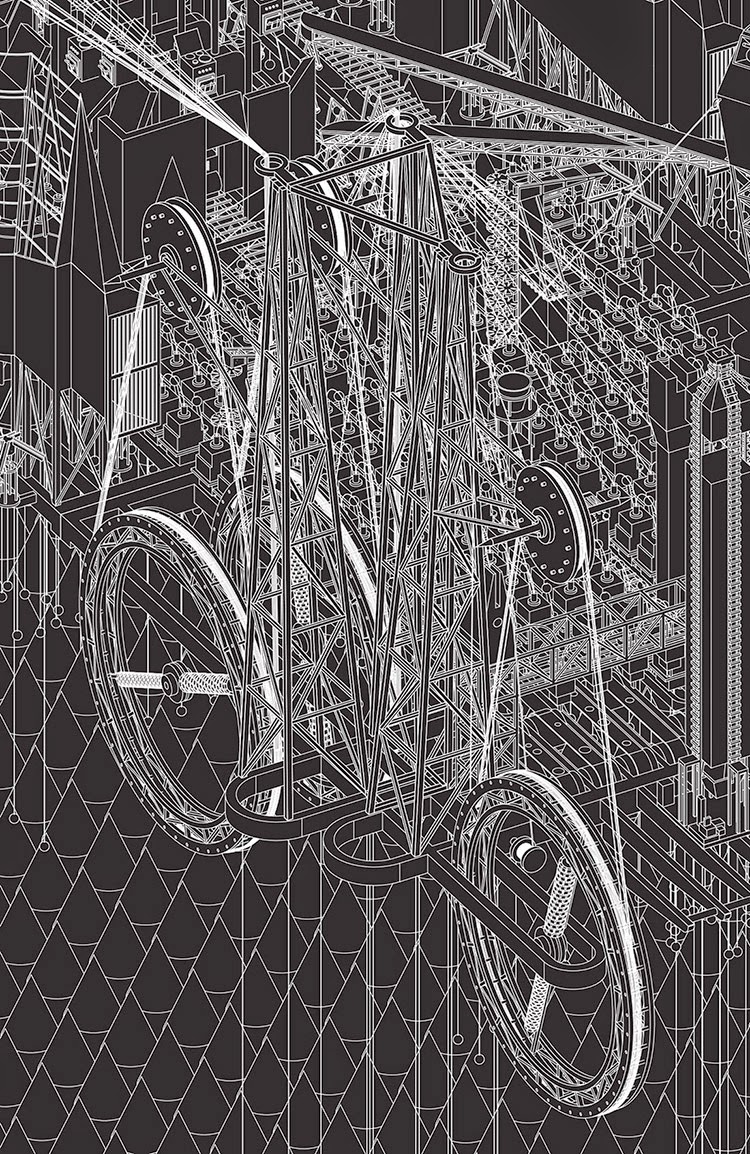

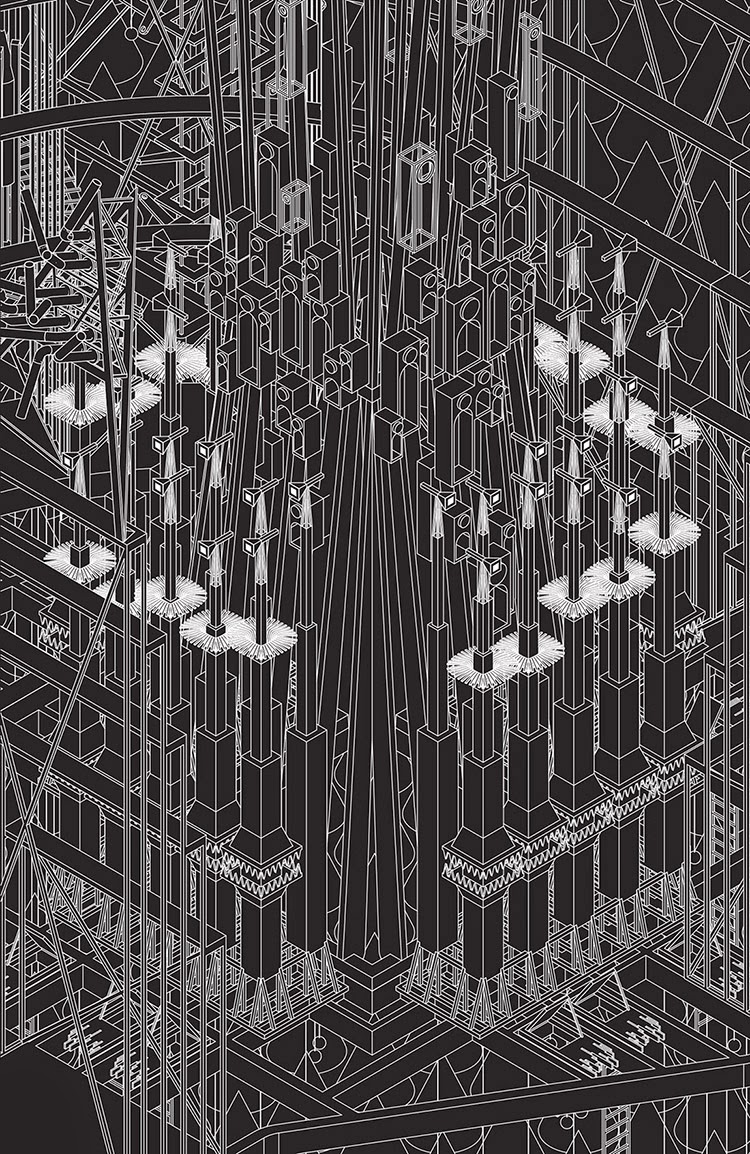

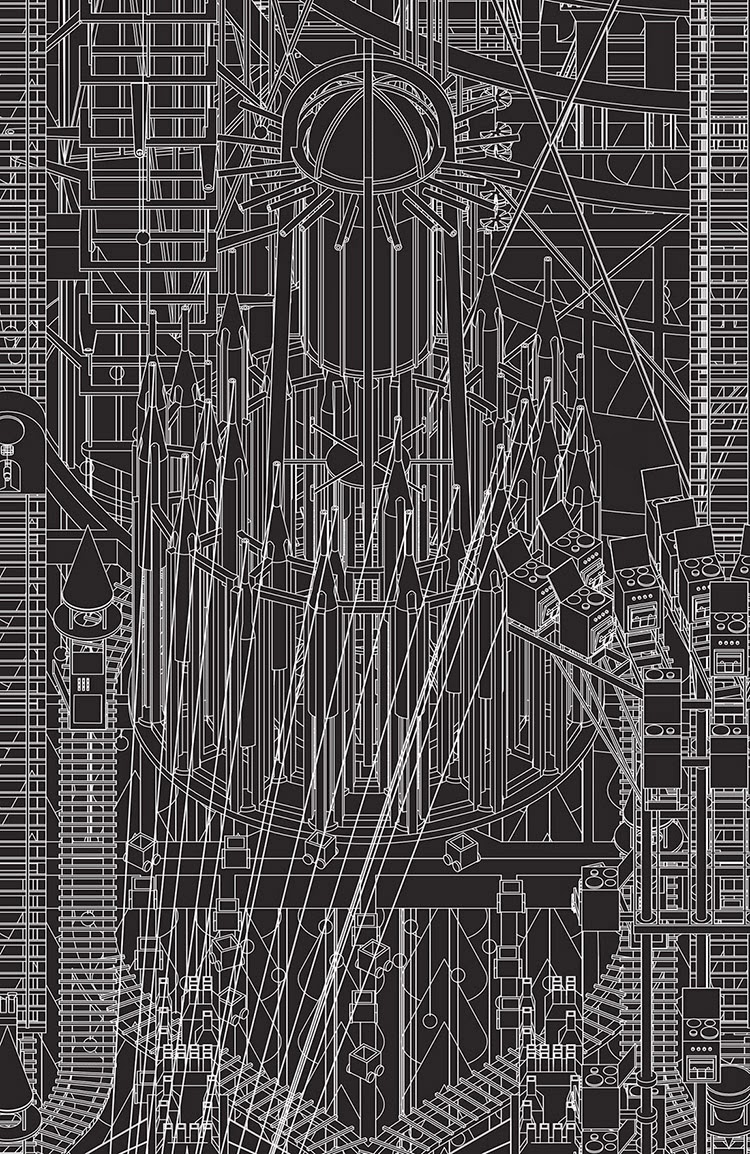

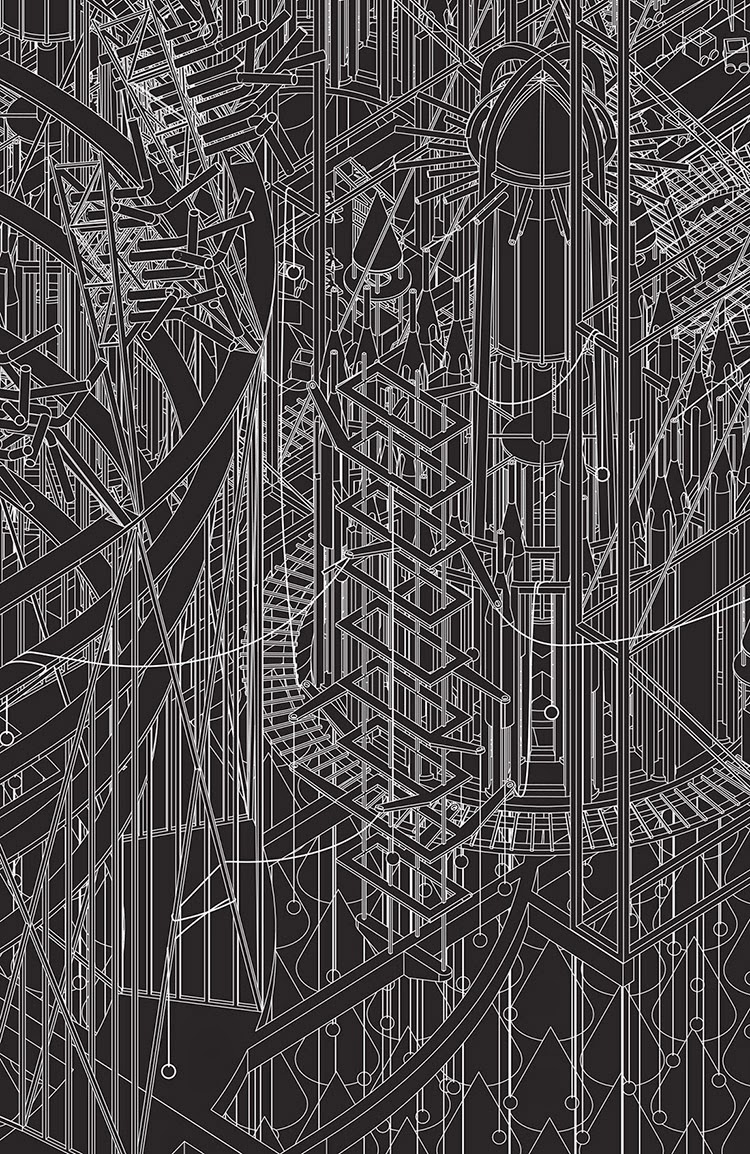

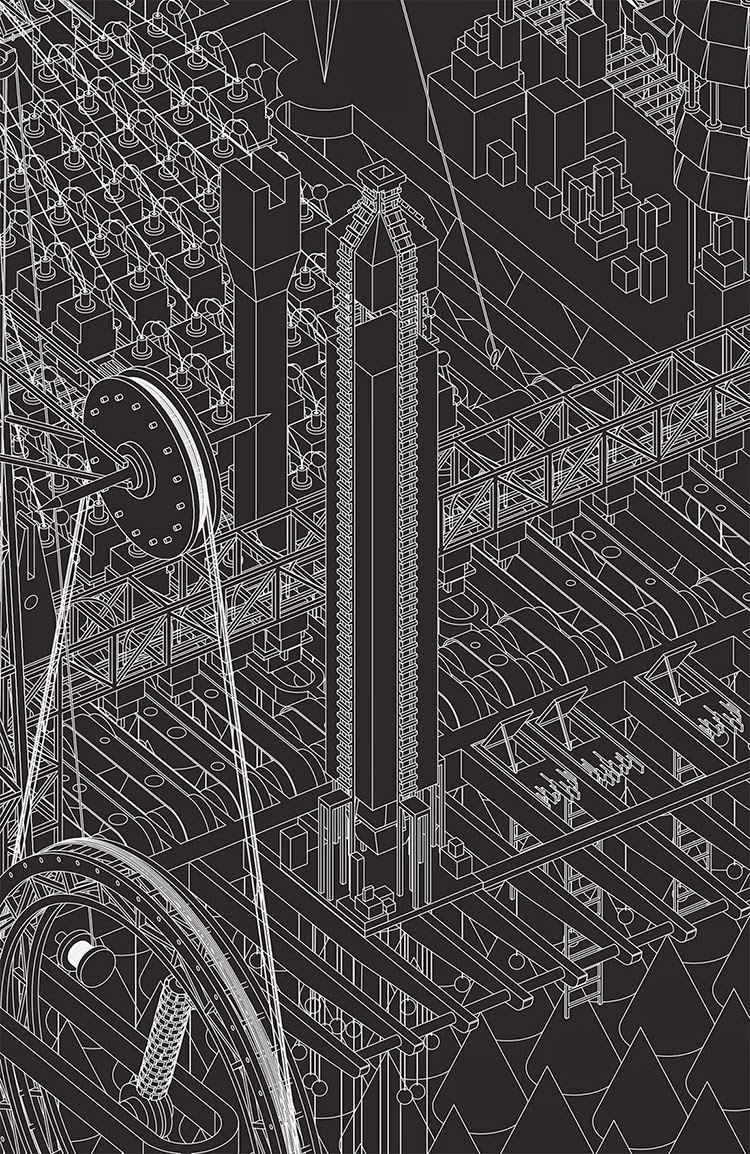

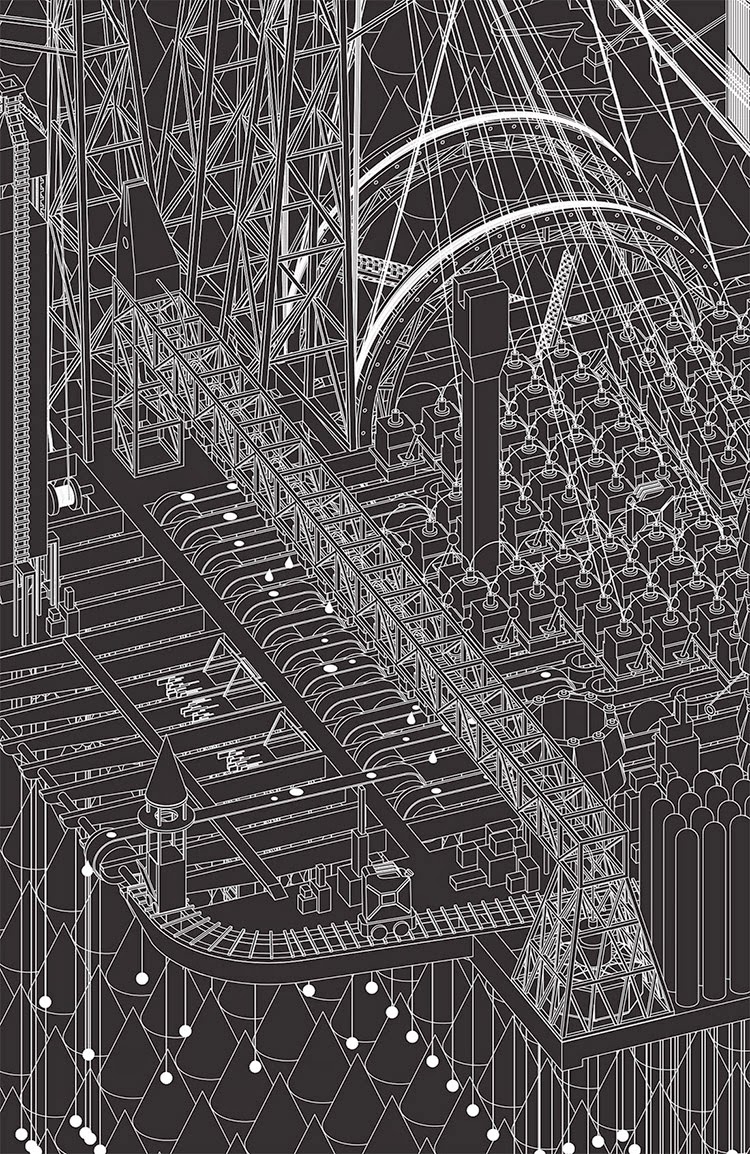

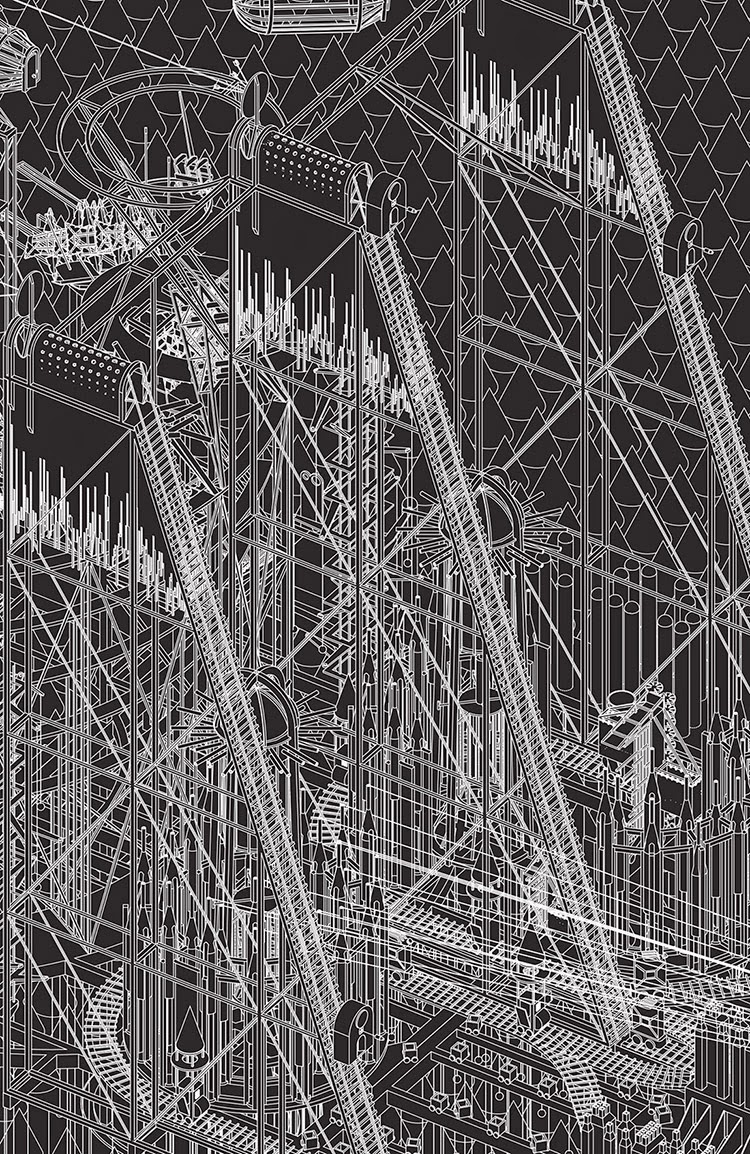

Grimm City

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Later this summer, London’s Flea Folly Architects—Pascal Bronner & Thomas Hillier—will be running a workshop in what they broadly call “narrative architecture” at the Tate Modern.

“What would a town inhabited by Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Man Ray look like?” they ask. “Taking inspiration from works in the Tate collection, in particular the speculative etchings by architects Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin and paintings by the Surrealists, our objective is to design and build a fictional miniature village made entirely from paper.”

Their own project, Grimm City, is perhaps an example of what might result.

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

As architect CJ Lim describes it in his introduction to the project in a gorgeously produced, limited print-run hardcover catalog, as “Grimm City is a future state derived from architectural extrapolations of the fairytales by the Brothers Grimm.”

That is, it is an elaborate narrative disguised as a city—a story given urban form.

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Bronner and Hillier explain that the “blueprint” for their city was “conceived in ink exactly 200 years ago,” and “was shaped by 86 magnificent tales collected by two of the most distinguished storytellers of their time.”

They are referring, of course, to the Brothers Grimm.

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Briefly, in what now feels like another lifetime, when I was backpacking through Germany after graduating from college, I made a beeline to the small city of Marburg after reading that it was a university town overlooked by an 11th-century fort—and that it was also once home to the Brothers Grimm.

I showed up by train and spent a few days there, mostly reading Grimm stories, feeding ducks, and walking around the roads that spiraled up to the castle; and I later learned, with equal interest, that one of the weird coincidences of history would make Marburg the same city where a strain of hemorrhagic fever would be isolated.

The disease, which is now rather straight-forwardly called Marburg, seems a fittingly strange continuation of the stories of the Brothers Grimm, in terms of the dark and often fatal transformations humans can undergo.

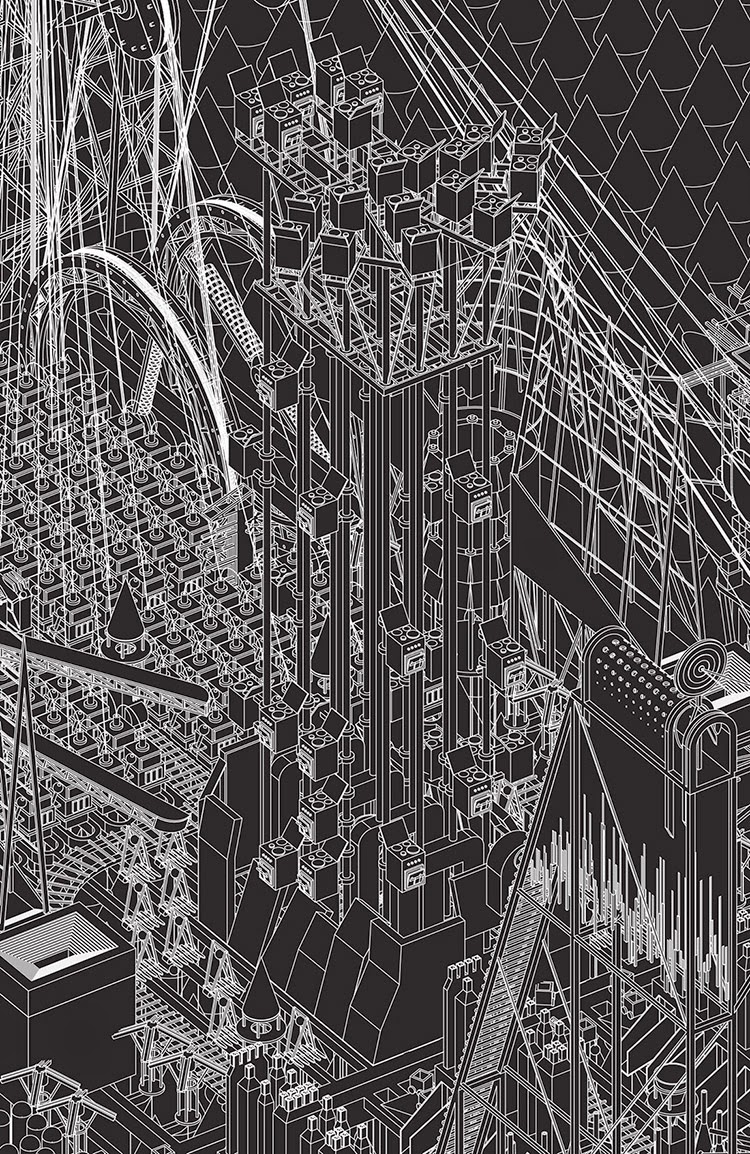

In any case, Grimm City is an architectural translation of their various stories, plots, allegories, and characters, and it took on a life of its own. “With enormous spinning wheels, tower-like limbs and turrets for claws, it began to resemble a machine that had been unjustly woken from its deep slumber,” they write.

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

At times visually reminiscent of Aldo Rossi or even John Hejduk, the black diagrams are unexpectedly carnivalesque, monochromatic yet fizzing with lively detail.

There are structures such as The Ink Factory, a Silver Forest (made entirely of money-producing slot machines, eg. a forest where silver grows), an economic Barometer spinning over the city, and a school of thieves and burglary.

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

There are also banks, churches, and a “windowless monolith” filled with forensic evidence of the city’s crimes.

Then, tacked way at the top of massive stairways so inclined they look like ladders, there are Confession Booths where the city’s sins are meant to be narrated and explained.

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Your exposure and isolation in ascending to the Booths is part of the process: a confessional infrastructure that compels one toward self-incrimination.

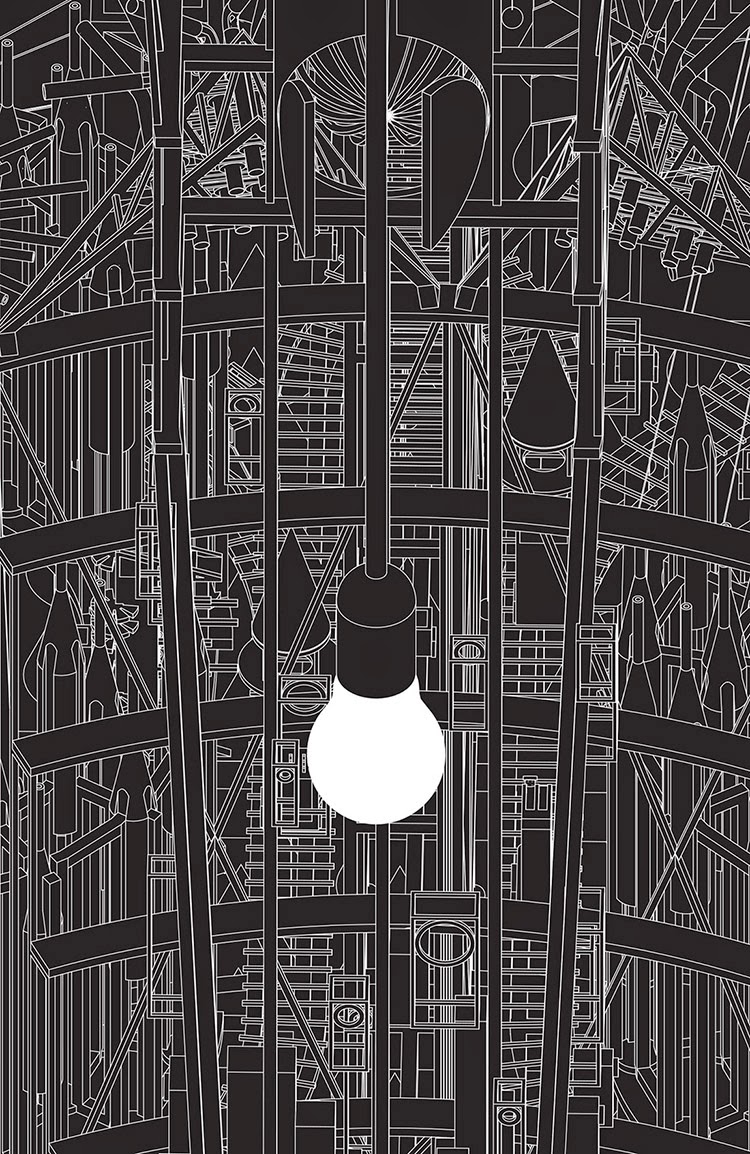

Elsewhere, there’s The Morning Star, a kind of heliogenic megabulb that hangs over the city, casting shadows and making time, burning at the center of an urban calendar that guides the lives of those living in the streets below.

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

And, finally, there is a huge plateau known as The Golden Compound where a vast sprawl—of what appear to be batteries—promises a “commune for the living-dead,” a dormitory those who “cheat death and remain everlasting” in this fairy tale metropolis.

“No one really knows if those inside” of these endless, battery-like structures, “are dead or alive,” we read, “and no one dares to find out.” They could be described as electrical mausoleums where sleeping beauties lie, equally alive and dead.

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

There are many, many further images, of course, as well as an intricate physical model that accompanied them; the whole thing was displayed at the London Design Museum back in October-November 2013 and, with any luck, the images and model both will someday show up in a gallery near you.

In a Pinch

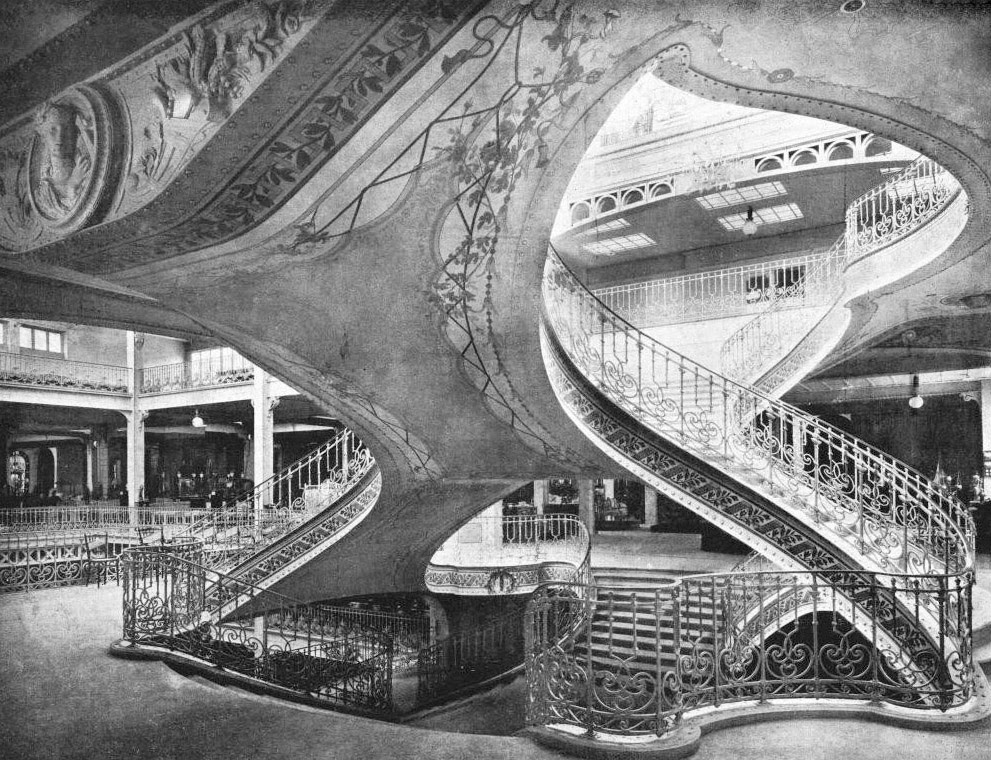

[Image: A staircase in the Grands Magasins Dufayel; view larger].

[Image: A staircase in the Grands Magasins Dufayel; view larger].

The second staircase I wanted to post today—here’s the first—is from the Grands Magasins Dufayel, a vast, 19th-century department store in Paris. View it larger.

Aside from the obvious grandeur of the structure, what makes this spatially noteworthy is the fact that one floor is pinched together with the next, and that the self-supporting “pinch” that results then becomes formalized as a stairway, a hyperbolic object in space that allows passage from one level to the next.

It’s as if a loop has been pulled or extracted from each level and then woven together—in effect, using a self-intersecting geometric pattern as the basis of a floorplan.

In any case, what I like in both examples (this one and the previous staircase), is that you have two floors or levels, obviously, but then there is the emptiness that separates them, a gap buzzing with unrealized forms of connection, and that you can fill that gap with pinches, spirals, knots, and loops, and that the magic of a well-designed staircase is precisely in giving material form to the invisible math that hovers in the space between floors.

(Originally spotted via ARCHI/MAPS).

Solved by Knots

[Image: Stairs inside the New York Life Insurance building, Minneapolis, by Babb, Cook and Willard; view larger].

[Image: Stairs inside the New York Life Insurance building, Minneapolis, by Babb, Cook and Willard; view larger].

There are two stairways I wanted to post, as they each solve the problem of getting from one floor to another in a particularly interesting way. The first example, seen above, is from the New York Life Insurance building in Minneapolis, Minnesota, designed by Babb, Cook and Willard.

View it larger.

What I love about this is incredibly simple, and it’s nothing more than the fact that a constrained approach from one floor to the next—with the far wall serving almost more like a cliff face—gave the architects no real room to operate. So they put in two, mirror-image spiral stairways, which kept the center of the room clear while dramatically increasing its available circulation space.

Today, of course, we’d probably just stick an elevator there and be done with it—but the compression of space made possible by spiral staircases is amazing. They are elegant prosthetics, connecting two levels like a casual afterthought with their efficient knots and coils.

Here’s the second staircase.

(Spotted via the always interesting ARCHI/MAPS).

Unconventional Sports Require Unconventional Spaces and Landscapes

[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via Architizer].

[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via Architizer].

Unconventional sports…

A profile of Reebok published the other week on Bloomberg Business—which you needn’t read, unless you are really into either shoe design or the global fitness industry—there’s a brief but interesting observation about what people seem to want to do these days, in terms of physical activity.

Not exercise, as such—which is the wrong way to think about it—but physically moving through space together and having a good time.

The article points out the obvious, for example, that CrossFit is on the rise, and that things like Tough Mudders, Spartan Races, etc., are all gaining in popularity; to this, I would also add climbing, which—based on my own entirely unscientific observations—appears to be undergoing its own boom time, at least gauged by the madhouse of over-attendance you often see at local climbing gyms in the hour after school gets out, turning a place like my local Brooklyn Boulders into an awesome new kind of home away from home for many local teenagers.

The article calls these “unconventional sports,” and they don’t require the traditional gym set-up. They require unconventional spaces and landscapes.

This is thus at least partially a question of design.

[Image: Via Brooklyn Boulders].

[Image: Via Brooklyn Boulders].

…require unconventional spaces and landscapes

The new emphasis is on “social fitness,” the article claims—but I’d say that even that phrase misses the primary motivation, which is really just screwing around with your friends, doing something fun, extreme, memorable, a little crazy, and simply different.

It means something that gets your heart rate up, lets you run around or climb on things for no reason to blow off steam, and that turns your immediate spatial environment into a place of often berserk new physical opportunities—another way of saying that you can literally climb the walls.

It’s like The Purge meets phys ed—not just “exercise,” with all the moral overtones of such a misused word.

[Image: Via CrossFit].

[Image: Via CrossFit].

“We’ve seen a real shift in the fitness world away from using heavy equipment like treadmills and stair climbers and toward much more social, class-based fitness—Zumba, Pilates, yoga, CrossFit,” an analyst named Matt Powell explains to Bloomberg Business. “These activities are really ramping up. So for a brand to stake out the fitness activity as their cornerstone makes a lot of sense right now.”

He’s talking about Reebok exploring new shoe designs made specifically for CrossFit and other forms of unconventional training apparel—but I’m genuinely curious what the architectural implications are in such a shift. Put another way, if Reebok was an architecture firm in charge of high school gymnasiums, what would this corporate revelation do to their spatial products? If what people physically do together has shifted toward the social, how might school gyms follow suit?

This isn’t just idle, Archigram-meets-Gold’s-Gym speculation. It we want to reverse the utterly insane trend toward removing gym class from children’s educational experiences, then it’s 100-times more likely that we’ll be able to do so not by cracking the whip harder and turning schools into militarized boot camps, but by designing spatial environments in which kids can do the things they actually want to do, where “exercise” is just a beneficial side-effect.

Even if that means adding BMX tracks, parkour competitions, trapeze routines, or—why not?—afternoon mud fights.

[Image: Via Clif Bar].

[Image: Via Clif Bar].

“Recess has been reduced or eliminated in many schools”

As Kaiser Permanente has pointed out, “the trend line for physical activity and education in schools is headed downward. As of 2006, only 4 percent of elementary schools, 8 percent of middle schools, and 2 percent of high schools nationwide provided daily physical education. Even recess has been reduced or eliminated in many schools.” This is horrifying.

Yet, if you stop by a place like the aforementioned Brooklyn Boulders on a weeknight, you’ll see not only that the place is often packed with teenagers who are as stoked as hell to be out of the classroom, doing weird physical things together, but that, awesomely, it’s often the very kids most often stereotyped as not giving a crap about exercise who are there hanging out and literally climbing the walls.

How can it be that gym class—or, more broadly speaking, physical activities in American schools—are so out of touch with what kids actually want to do these days that kids need to make a bee-line to the nearest climbing gym to burn off all their energy?

Is this purely a liability issue—because everyone’s perfect angel might scrape a knee—or has there been a failure of spatial imagination amongst the people building gyms and playgrounds today?

[Images: Ray’s MTB].

[Images: Ray’s MTB].

Just think of the underground bike park in Louisville or even just a local skatepark—or, for that matter, any of the more youth-oriented playgrounds I wrote about a few years ago for Popular Science.

In fact, just the other week, my wife and I were learning how to do 40-foot high falls off of scaffolding inside a warehouse over in Greenpoint as part of this random stunt-training thing we did. We were in a cavernous room full of huge mats, climbing walls, an oversized trampoline, and all sorts of other random things, like swords—and, what do you know, but there were also tons of kids of there, from the genuinely young to teenagers going through the most awkward phase of teenagerness, and there was no evidence on display that we live in a world where kids don’t want to do weird physical things together.

In other words, most people do want to “get exercise,” as it is unfortunately and rather Calvinistically known; they just want to do in a way where it’s a side-effect of having fun.

[Images: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photos courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

[Images: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photos courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

“I will be multifaceted”

Outdoor design consultant Scott McGuire of The Mountain Lab said something really interesting in a long interview published here back in 2013. McGuire suggested that “sport specificity” is being thrown out the window these days in favor of a general state of pure physical activity. Or, in his words:

When I grew up, you were a surfer or you were a skater or you were a climber or you were a road biker. But kids today don’t think anything like that—they think, “I do all of those things! Why would I not be someone who is a skier who’s also into bouldering who’s taking up trail running and who competes in Wii dance competitions? Why can’t I be that person?” There’s a sense that I will be whoever I want to be, whenever—and, of course, I will be multifaceted.

McGuire went on to suggest, similar to the Bloomberg Business article cited above, that “this is a generation who don’t see why they can’t leave the trail, go to town, have lunch, and go to the skate park and skate all afternoon, and not change gear. But the outdoor industry is having a hard time reconciling that.”

But, crucially, architects are having a hard time reconciling that, too. The spatial environments currently being designed and built to foster “exercise,” or physically engaged play, today rarely correspond to the activities people seem most excited to pursue.

In fact, I’d suggest that this is part of a much larger narrative, one that includes the decline in interest in heavily formalized Olympic sports, where the rise of alternative activities, such as X Games, parkour, BMX, and skateboarding, are proof that something else could very well fill that niche, but our spatial environments are lagging too far behind.

[Image: The Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark, via The Skateboarder Mag].

[Image: The Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark, via The Skateboarder Mag].

Designing the gym of tomorrow

If at least part of the crisis in phys ed today is that school gyms are simply being built wrong, then the obvious next question would be: what should they really look like?

This is, among other things, an architectural problem: what sorts of physical activities have been designed out of the school environment—not to mention the city, the suburb, the home, or the office?

Conversely, what activities should the schools, gyms, and buildings of today actually foster or allow?

[Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via Architizer].

[Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via Architizer].

At the most mundane level, could the architecture of the school building itself somehow absorb or otherwise channel the infamous distractibility and hyper-activity of kids today into deliberately frivolous physical activities (that is, “exercise”)?

In other words, if it looks like those kids in the back of class are literally about to climb the walls from eating too much breakfast cereal, then why not let them? Put whole spiraling labyrinths of climbing walls and tunnels throughout the school, with mats and helmets everywhere, and make exploring these inner wilds a genuine reward for sitting still in class.

There is nothing radical in such an observation, but it is nonetheless a genuine and important social issue: how to inspire, not to mention architecturally encourage, intense physical activity at all ages.

It’s not just urban design that’s “making us fat,” which is, after all, just an overly moralizing way of saying that urban design doesn’t let us have fun. It’s the fact that almost none of our buildings, including our schools and playgrounds, have been built to allow the kinds of physical activities people actually want to engage in these days.

[Image: Aerial view of the Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark].

[Image: Aerial view of the Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark].

So, if we go back to the Reebok example from the very beginning of this post, we’ll find an architectural conversation hiding in the details. We see a company realizing that its products no longer correspond to what its potential consumers actually want to do, and then forcing itself to fundamentally redesign those products in order to reflect the needs of this overlooked market.

What is the architectural—or more broadly speaking spatial—equivalent of this, and what should the gyms, schools, and playgrounds of tomorrow actually look like?

To Reach Mars, Head North

[Image: An early design image of Fermont, featuring the “weather-controlling super-wall,” via the Norbert Schonauer archive at McGill University].

[Image: An early design image of Fermont, featuring the “weather-controlling super-wall,” via the Norbert Schonauer archive at McGill University].

I’ve got a new column up at New Scientist about the possibility that privately run extraction outposts in the Canadian north might be useful prototypes—even political testing-grounds—for future offworld settlements.

“In a sense,” I write, “we are already experimenting with off-world colonization—only we are doing it in the windswept villages and extraction sites of the Canadian north.”

For example, when Elon Musk explained to Ross Anderson of Aeon Magazine last year that cities on Mars are “the next step” for human civilization—indeed, that we all “need to be laser-focused on becoming a multi-planet civilization”—he was not calling for a second Paris or a new Manhattan on the frigid, windswept plains of the Red Planet.

Rather, humans are far more likely to build variations of the pop-up, investor-funded, privately policed, weather-altering instant cities of the Canadian north.

The post references the work of Montréal-based architectural historian Alessandra Ponte, who spoke at a conference on Arctic futures held in Tromsø, Norway, back in January; there, Ponte explained that she had recently taken a busload of students on a long road trip north to visit a mix of functioning and abandoned mining towns, including the erased streets of Gagnon and the thriving company town of Fermont.

Fermont is particularly fascinating, as it includes what I describe over at New Scientist as a “weather-controlling super-wall,” a 1.3km-long residential mega-complex specifically built to alter local wind patterns.

Could outposts like these serve as examples—or perhaps cautionary tales—for what humans will build on other worlds?

Modular buildings that can be erased without trace; obscure financial structures based in venture capital, not taxation; climate-controlling megastructures: these pop-up settlements, delivered by private corporations in extreme landscapes, are the cities Elon Musk has been describing.

Go check out the article in full, if it sounds of interest; and consider picking up a copy of Alessandra Ponte’s new book, The House of Light and Entropy, while you’re at it, a fascinating study of landscape, photography, mapping, geographic emptiness, the American West, and the “North” as a newly empowered geopolitical terrain.

Finally, don’t miss this interesting paper by McGill’s Adrian Sheppard (saved here as a PDF) about the design and construction of Fermont, or this CBC audio documentary about life in the remote mining town.

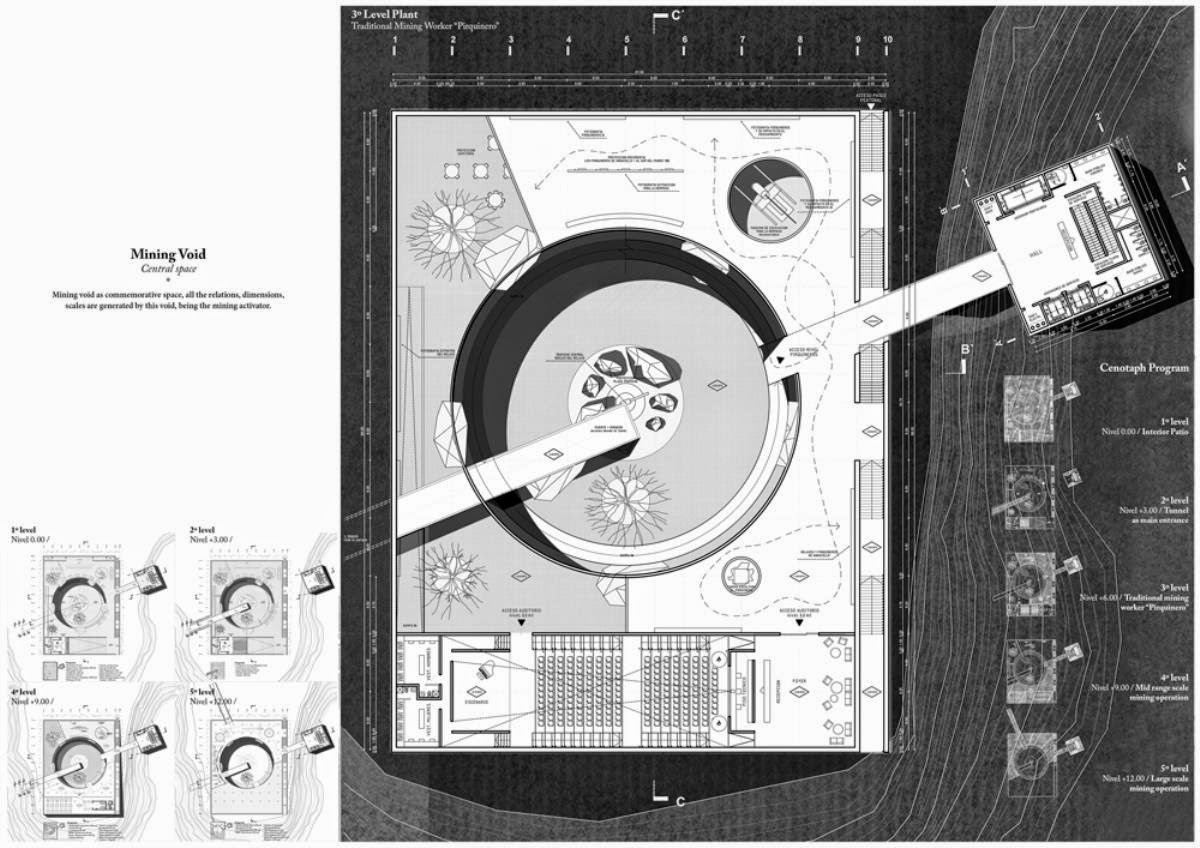

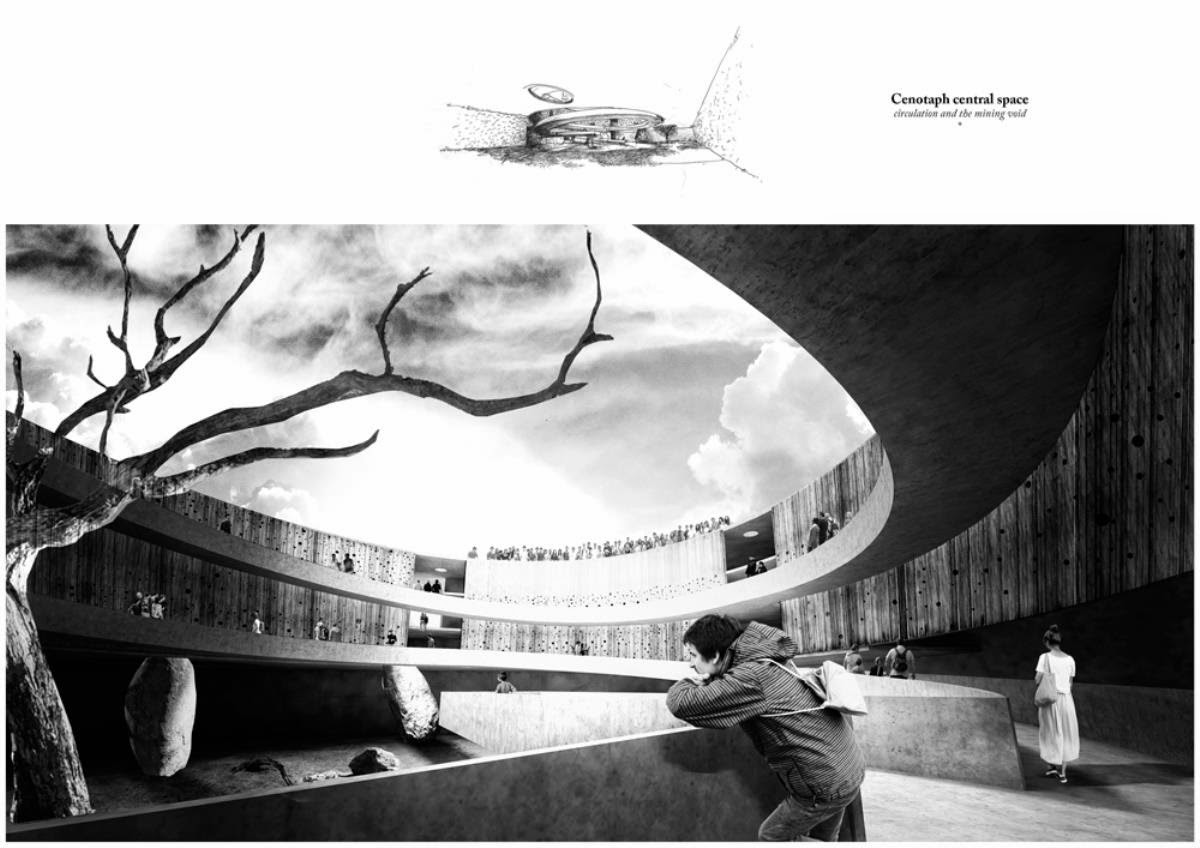

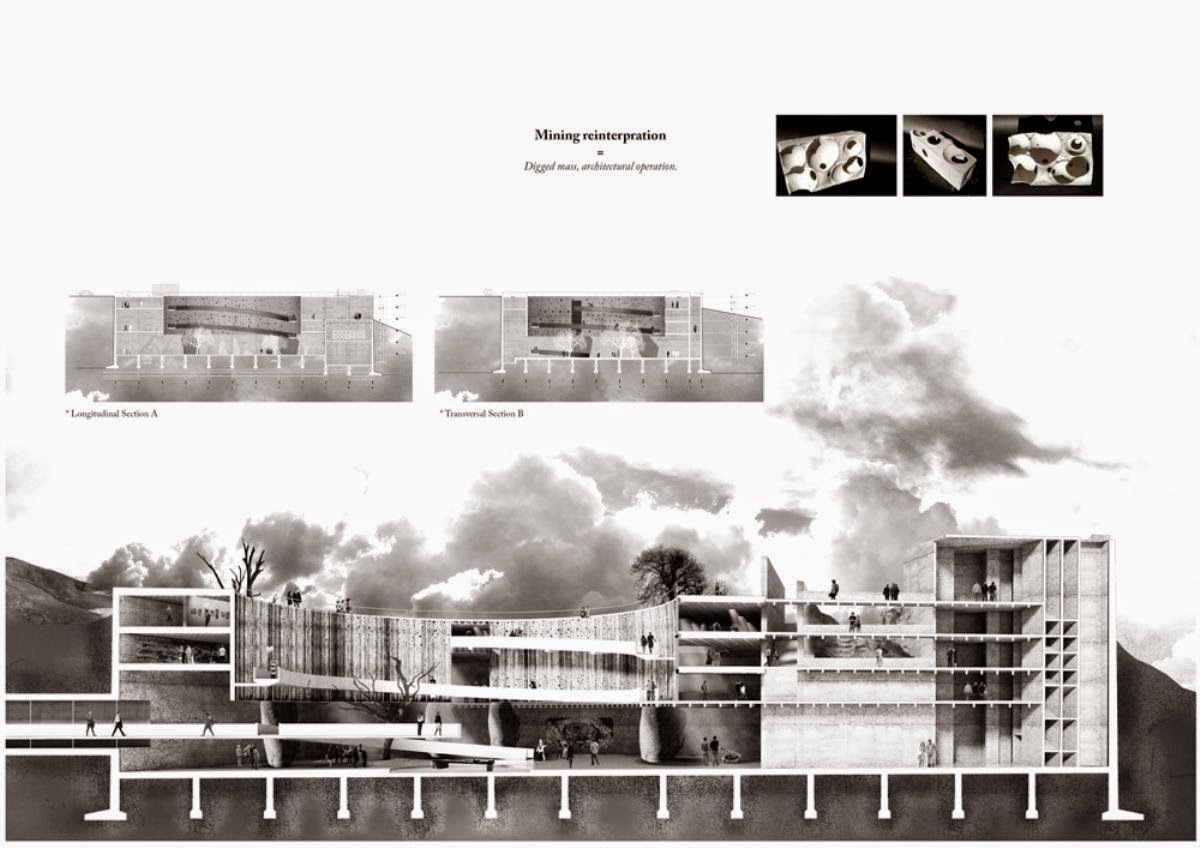

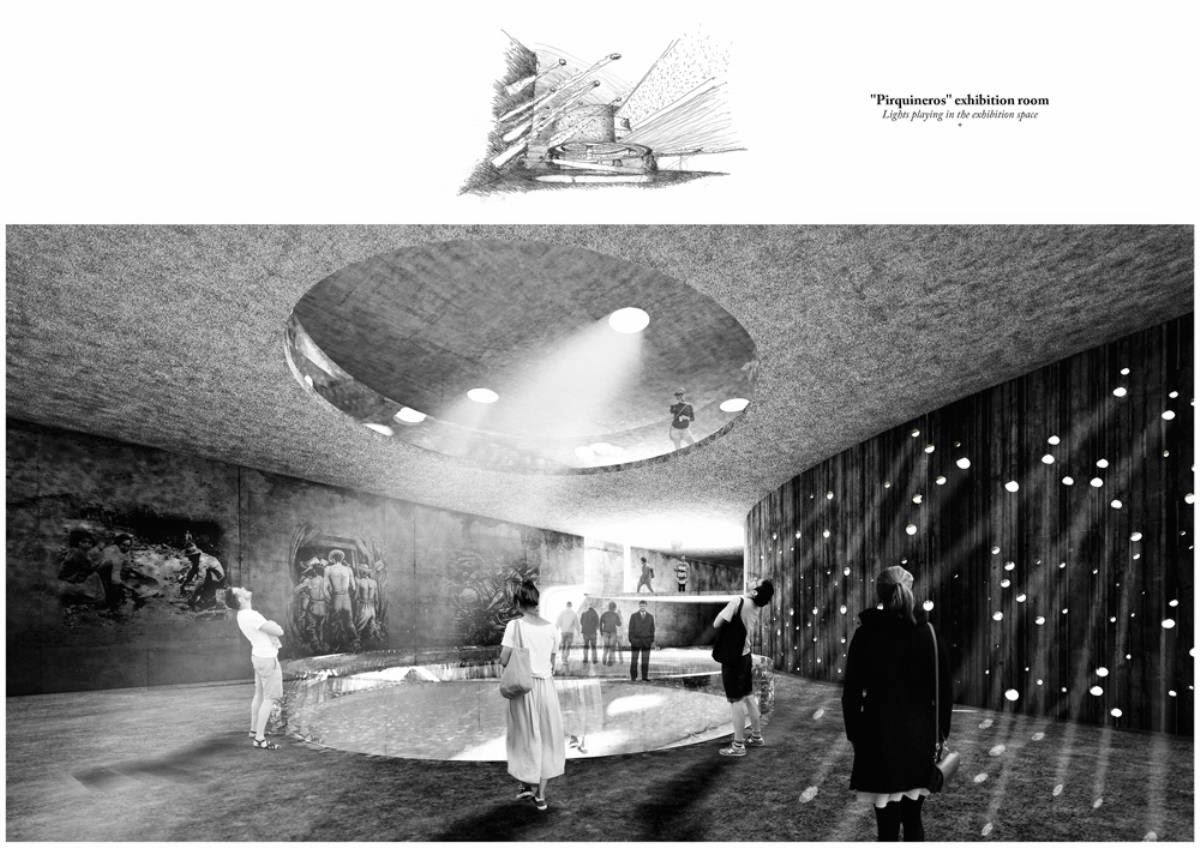

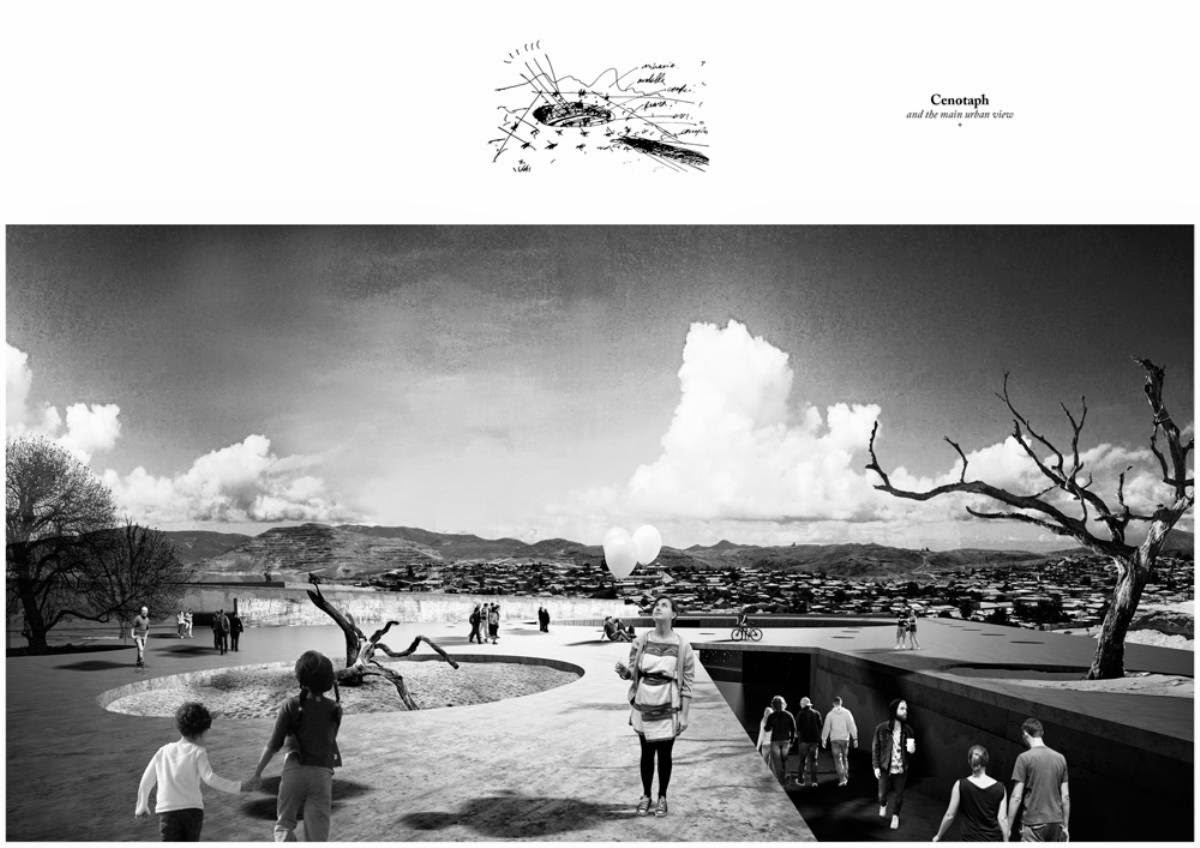

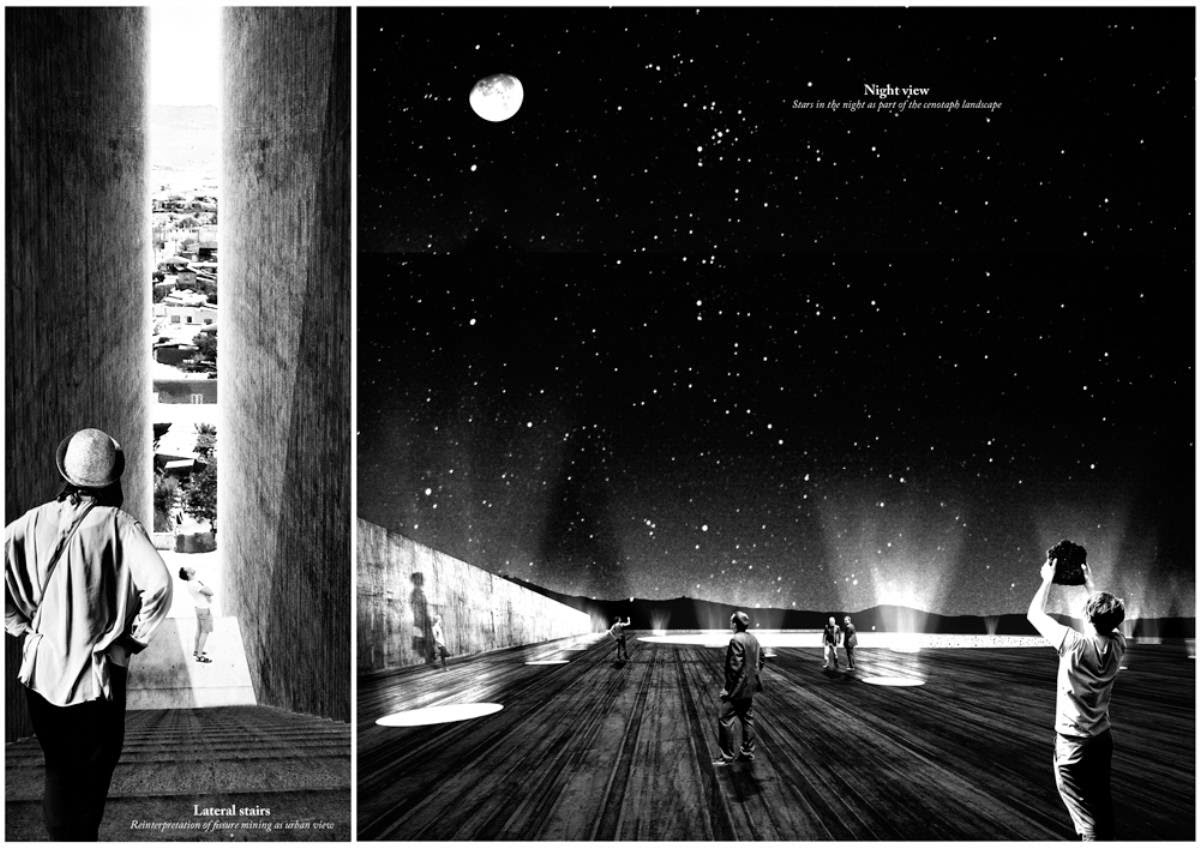

A Cenotaph for Tailings

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

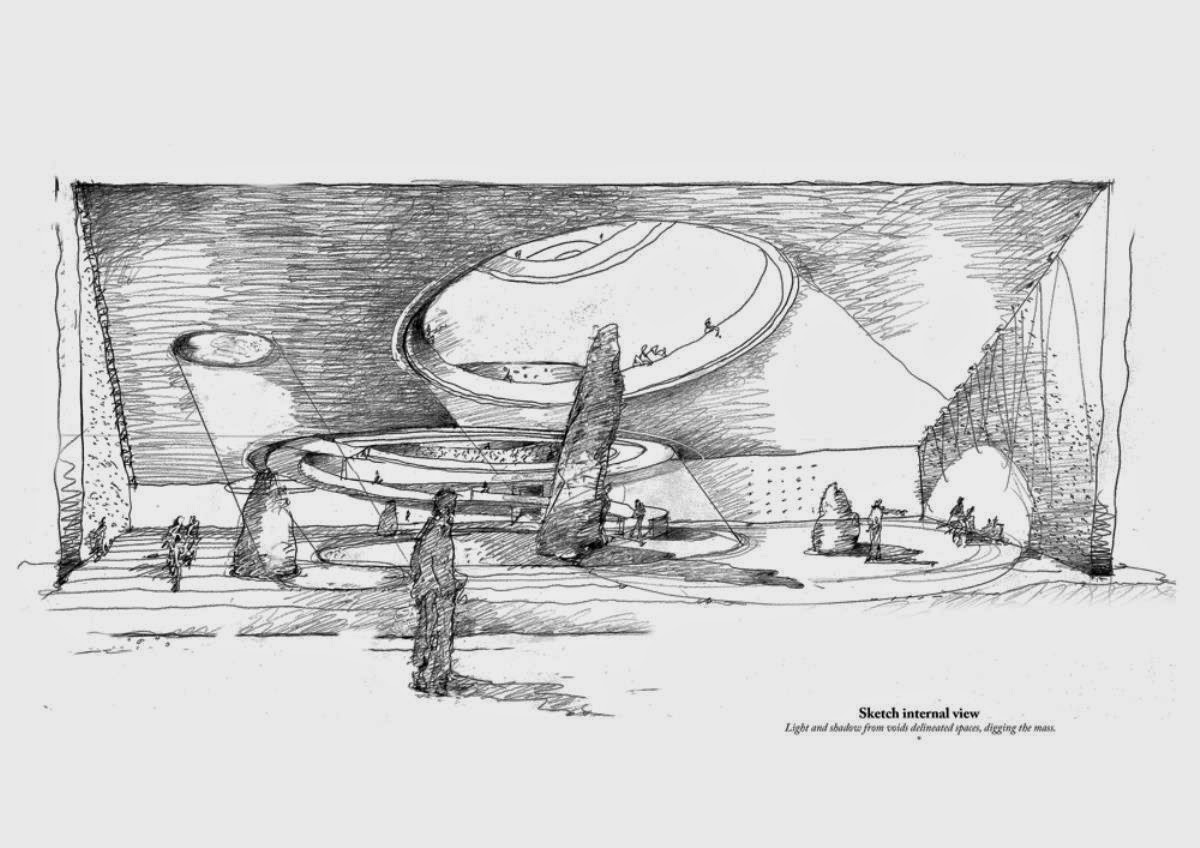

Here’s another project from the RIBA President’s Medals, this one by Alexis Quinteros Salazar, a student at the University of Chile in Santiago.

Called “Mining Cenotaph,” it imagines an “occupation” of the tailings piles that have become a toxic urban landmark and a spatial reminder of the region’s economic exploitation.

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

A museum would be carved into the tailings; in Salazar’s words, this would be a “building that captures the history and symbolism behind mining, enhancing and revitalizing a memory that is currently disaggregated and ignored and has a very high touristic potential.”

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

In an architectural context such as this, the use of the word “cenotaph” is a pretty clear reference to Étienne-Louis Boullée’s classic speculative project, the “Cenotaph for Newton.” Over multiple generations, that has become something of a prime mover in the history of experimental architectural design.

Punctured walls and ceilings bring light into the interior—

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

—while the roof is a recreational space for visitors.

Of course, there are a lot of unanswered questions here—including the control of aerosol pollution from the tailings pile itself and that pile’s own long-term structural stability—but the poetic gesture of a public museum grafted into a pile of waste material is worth commending.

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

The detail I might like this most is where the structure becomes a kind of inversion of Boullée’s dome, which was pierced to make its huge interior space appear illuminated from above by constellations. Here, instead, it is the perforations in the the rooftop that would glow upward from below, as if in resonance with the night skies high above.

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

Salazar’s project brings to mind a few other proposals seen here over the years, including the extraordinary “Memorial to a Buried Village” by Bo Li and Ge Men, as well as Brandon Mosley’s “Mine Plug” (which actually took its name retroactively from that BLDGBLOG post).

Click through to see slightly larger versions of the images over at the RIBA President’s Medals website.

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Mining Cenotaph” by Alexis Quinteros Salazar; courtesy of the RIBA President’s Medals].

Finally, don’t miss the Brooklyn food co-op posted earlier, also a recent President’s Medal featured project.

Colossal Cave Adventure

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

An underground bike park is opening up next month in a former limestone mine 100 feet beneath Louisville, Kentucky.

At 320,000-square feet, the facility is massive. Outside Magazine explains, “the park will have more than five miles of interconnected trails that range from flowing singletrack to dirt jumps to technical lines with three-foot drops. And that’s just the first of three phases to roll out this winter.”

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

That’s from an interview that Outside just posted with the park’s designer, Joe Prisel, discussing things like the challenges of the dirt they’ve had to use during the construction process and the machines they used to sculpt it.

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

[Photo: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photo courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

It’s not the most architecturally-relevant interview, if I’m being honest, so there’s not much to quote here from it, but the very idea of a BMX super-track 10 stories underground in a limestone mine sounds like a project straight out of an architecture student’s summer sketchbook, and it’s cool to see something like this become real.

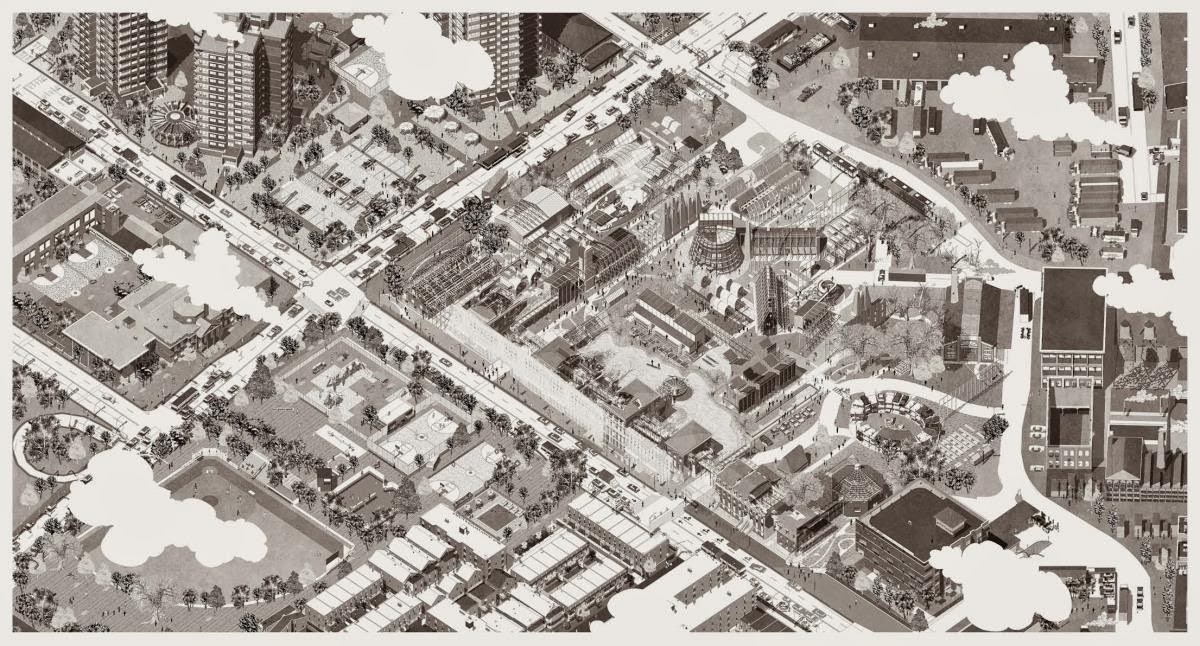

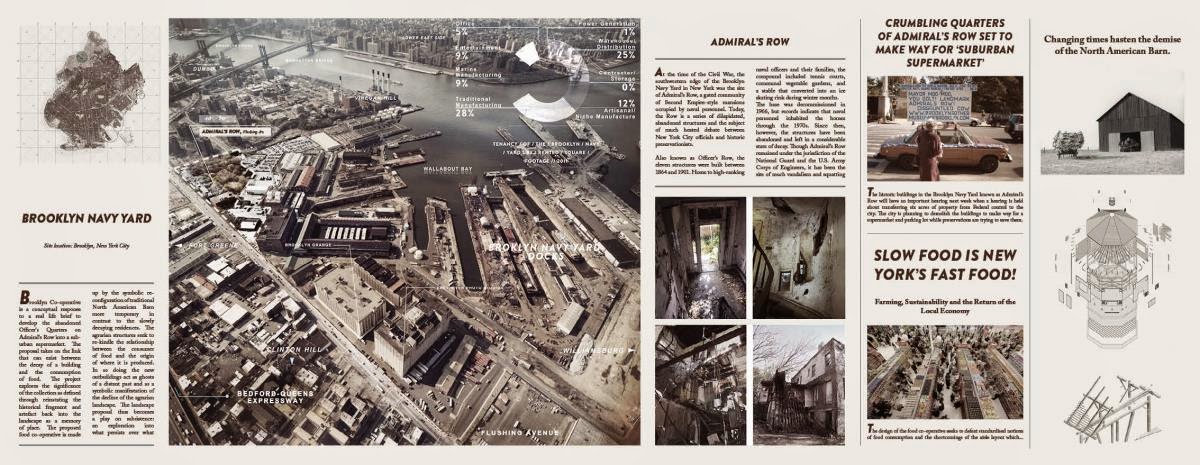

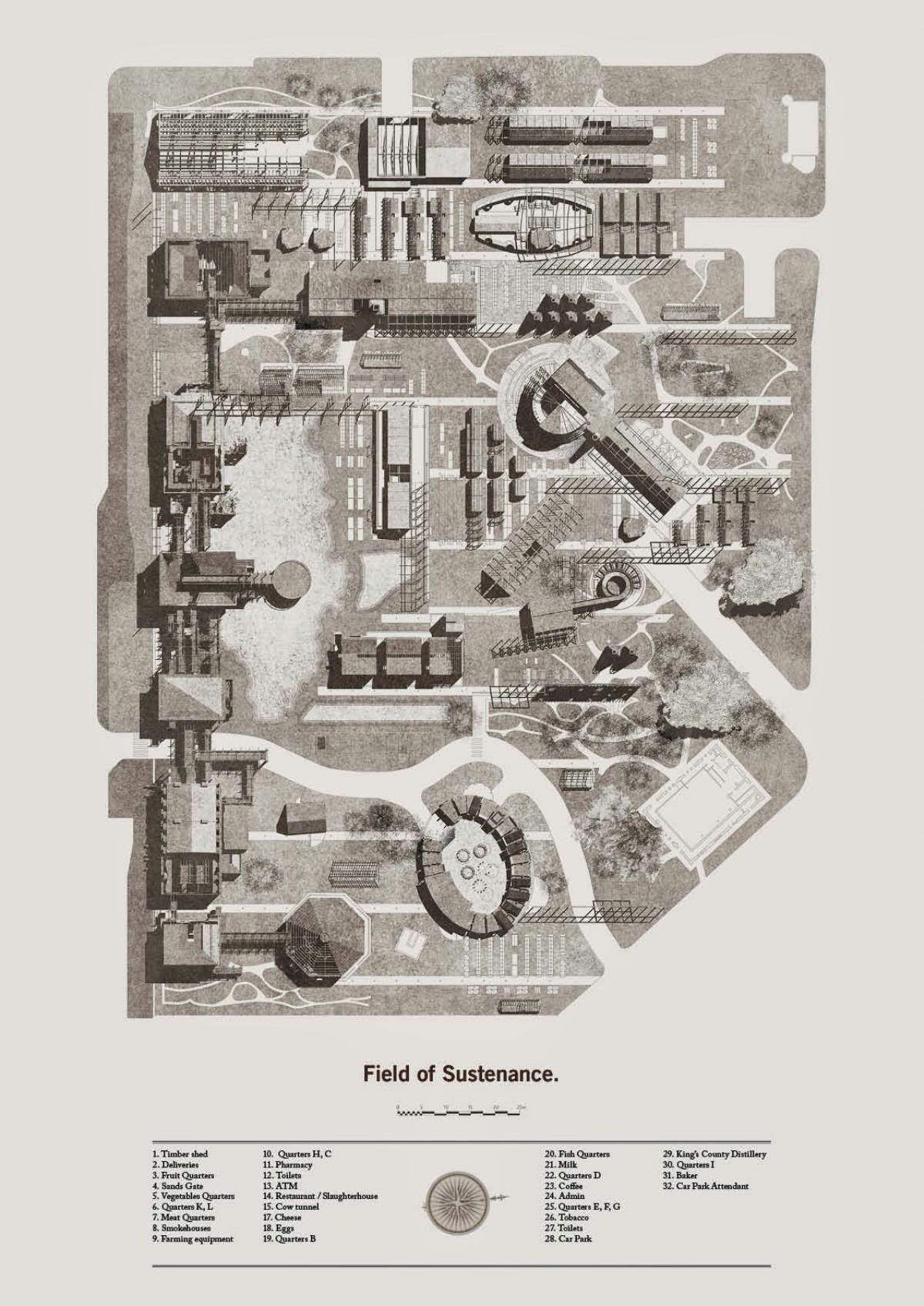

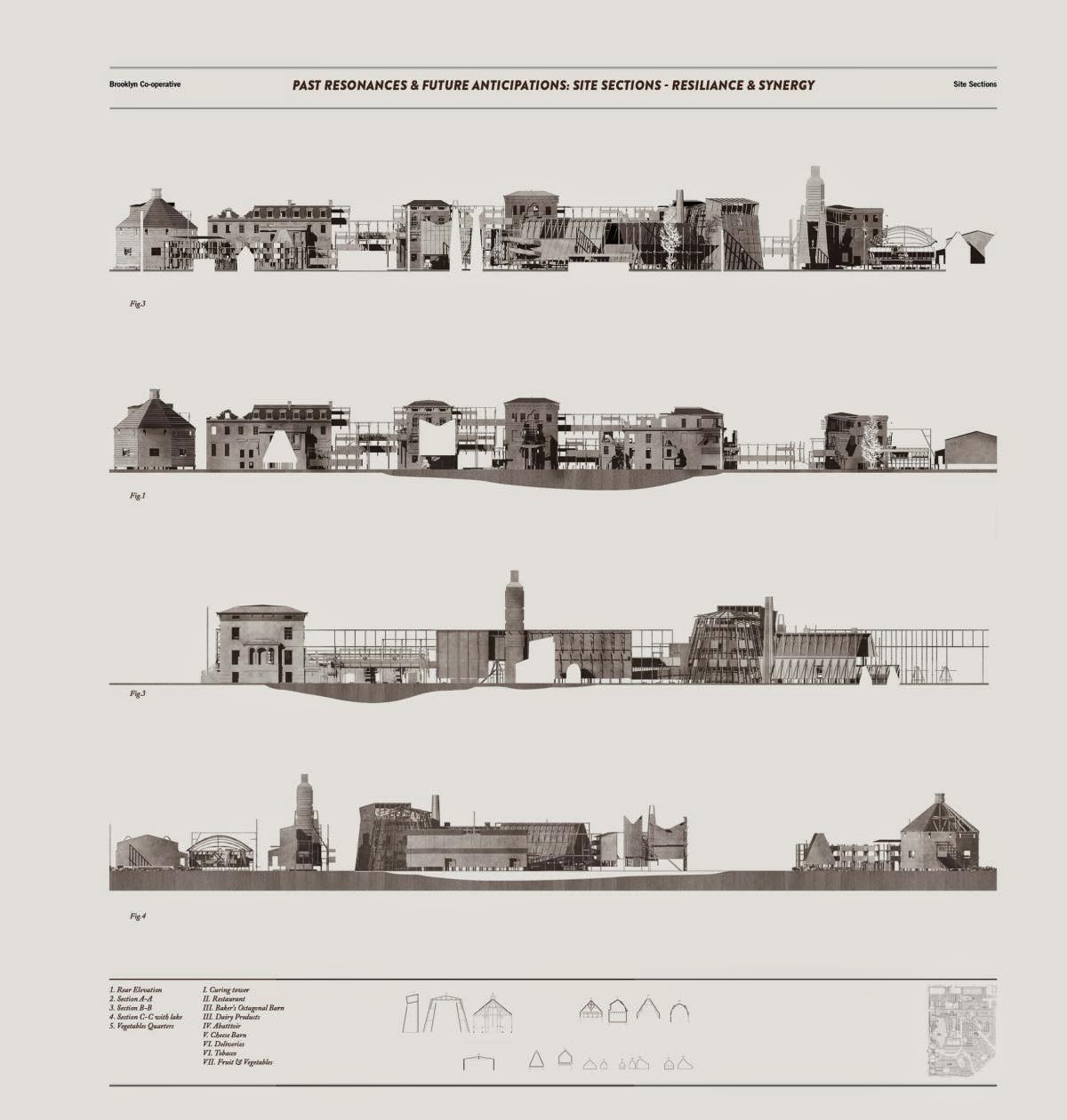

Brooklyn Super Food

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

I was clicking around on the RIBA President’s Medals website over the weekend and found a few projects that seemed worth posting here.

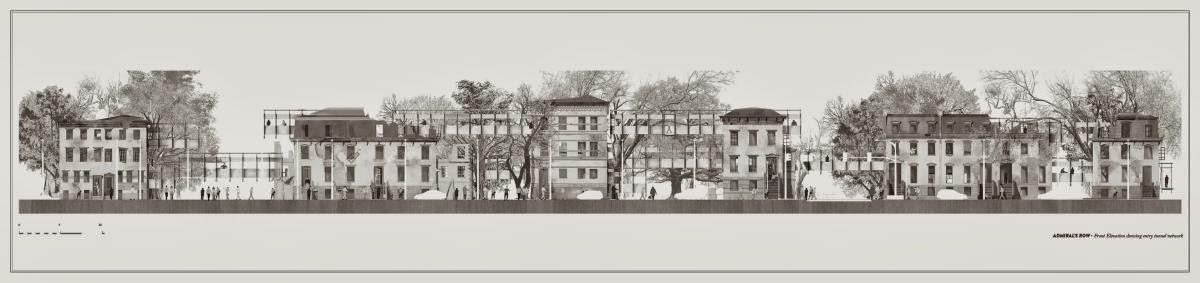

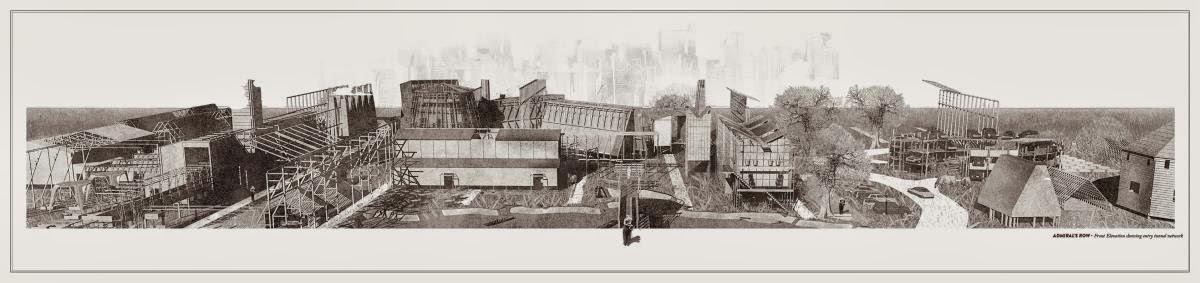

The one seen here is a beautifully illustrated proposal for an “alternative supermarket” in Brooklyn, New York, that would be located in the city’s old Navy Yard.

Note that, in all cases, larger images are available at the project website.

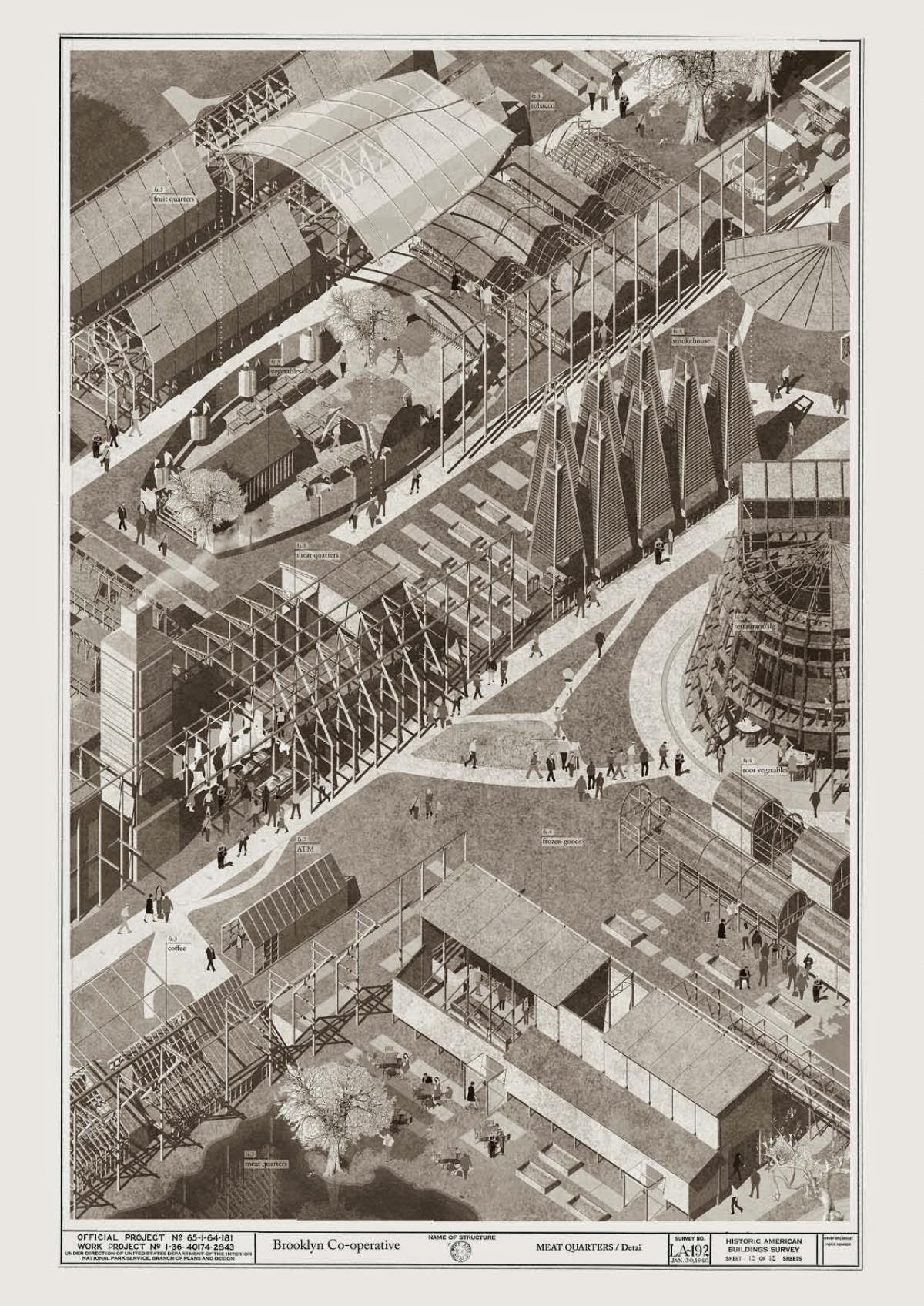

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

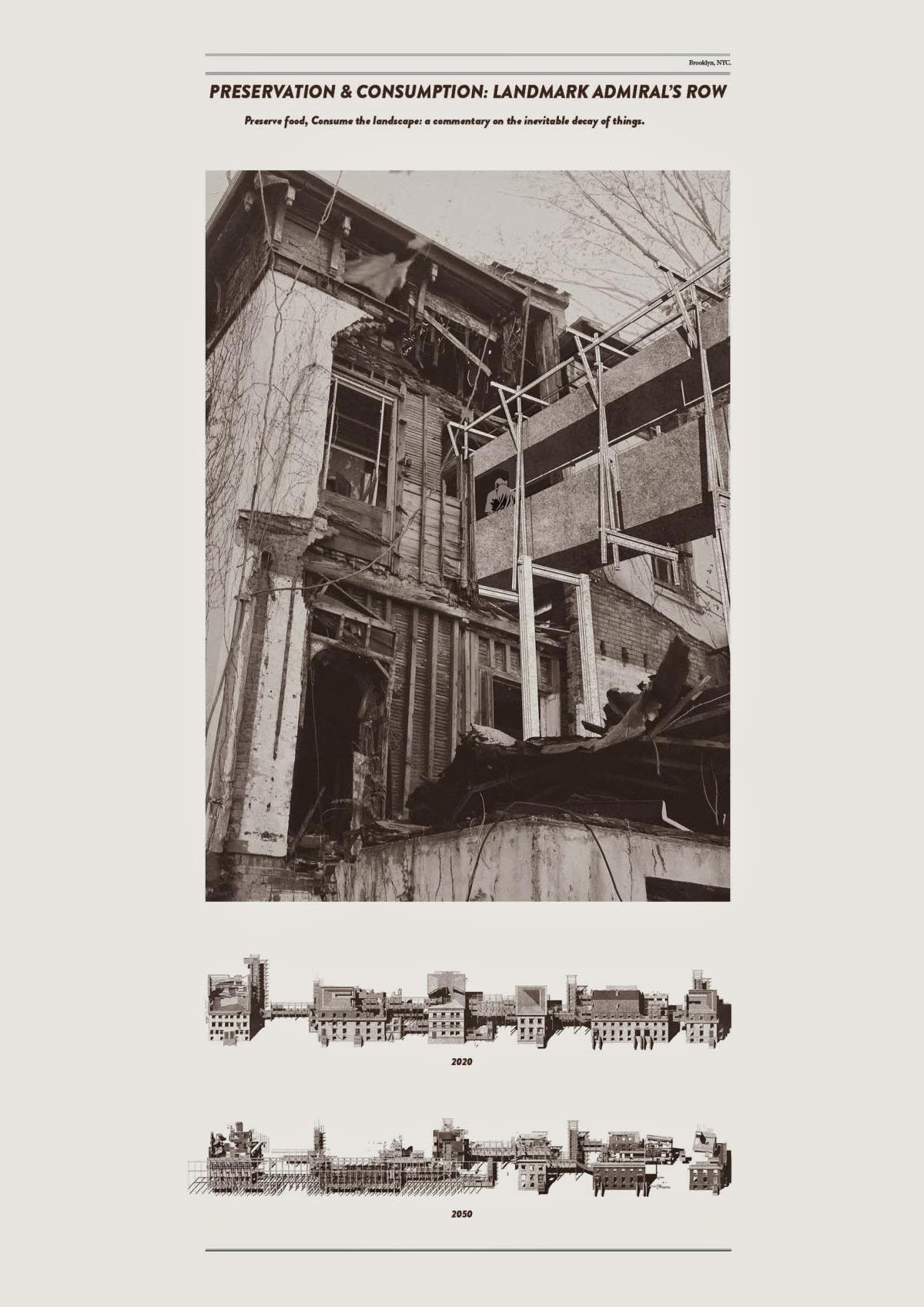

Its designer—Yannis Halkiopoulos, a student from the University of Westminster—pitches it as a food-themed exploration of adaptive reuse, a mix of stabilized ruins, gut renovations, and wholly new structures.

He was inspired, he suggests, by the architecture of barns, market structures, and the possibility of an entire urban district becoming a “reinvented artefact” within the larger economy of the city.

The results would be a kind of post-industrial urban food campus on the waterfront in Brooklyn.

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

From Halkiopoulos’s description of the project:

The project is a response to current plans which are to demolish the row of abandoned houses to build a suburban supermarket. Once home to high ranking naval officers the eleven structures have been left to decay since 1960. The response is an alternative food market which aims to incorporate the row of houses and re-kindle the consumer with the origin of the food produced and promote regional traditions, gastronomic pleasure and the slow pace of life which finds its roots in the Slow Food Movement NY.

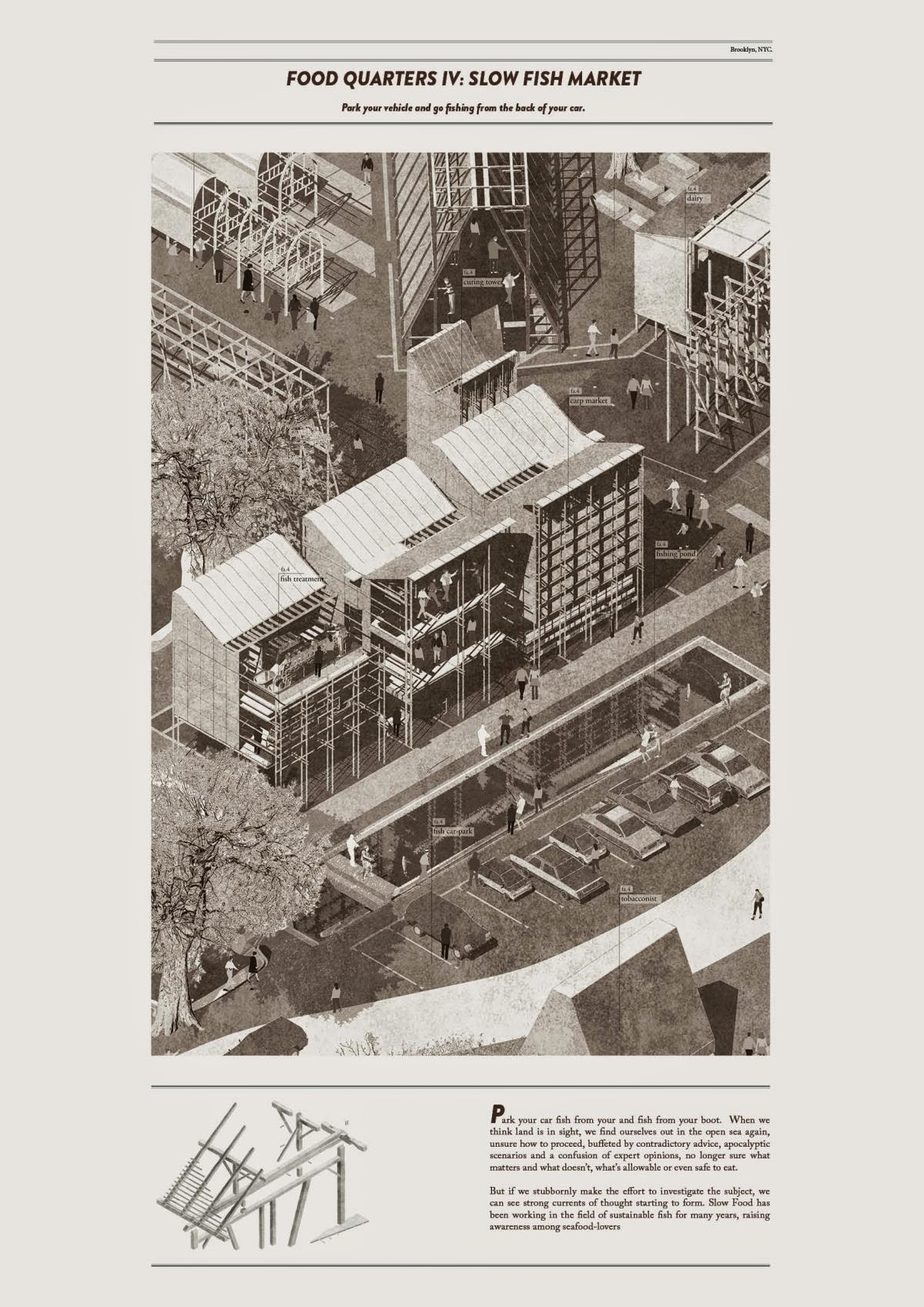

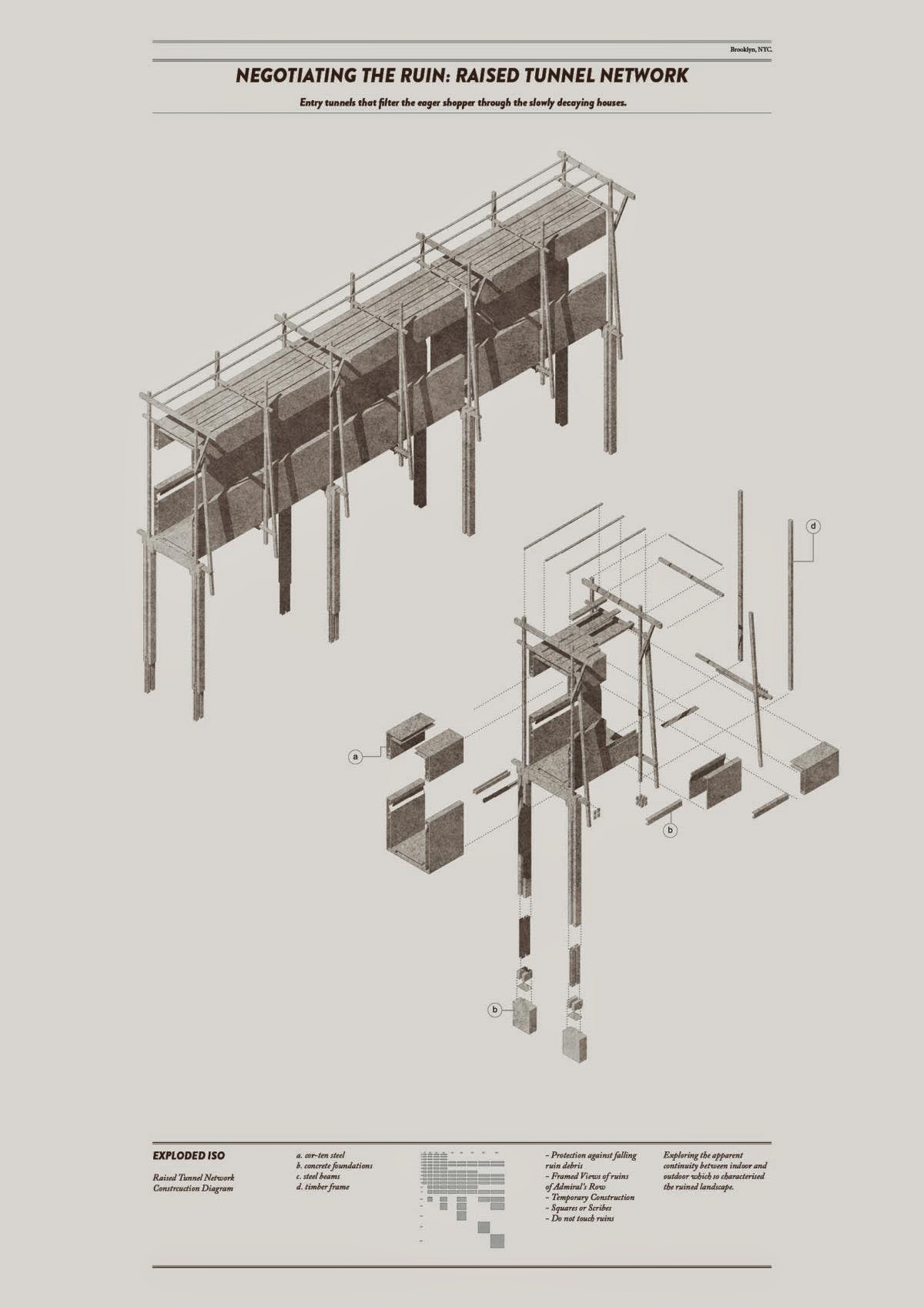

It includes a slaughterhouse, a “slow fish market,” preservation facilities, a “raised tunnel network” linking the many buildings, and more.

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

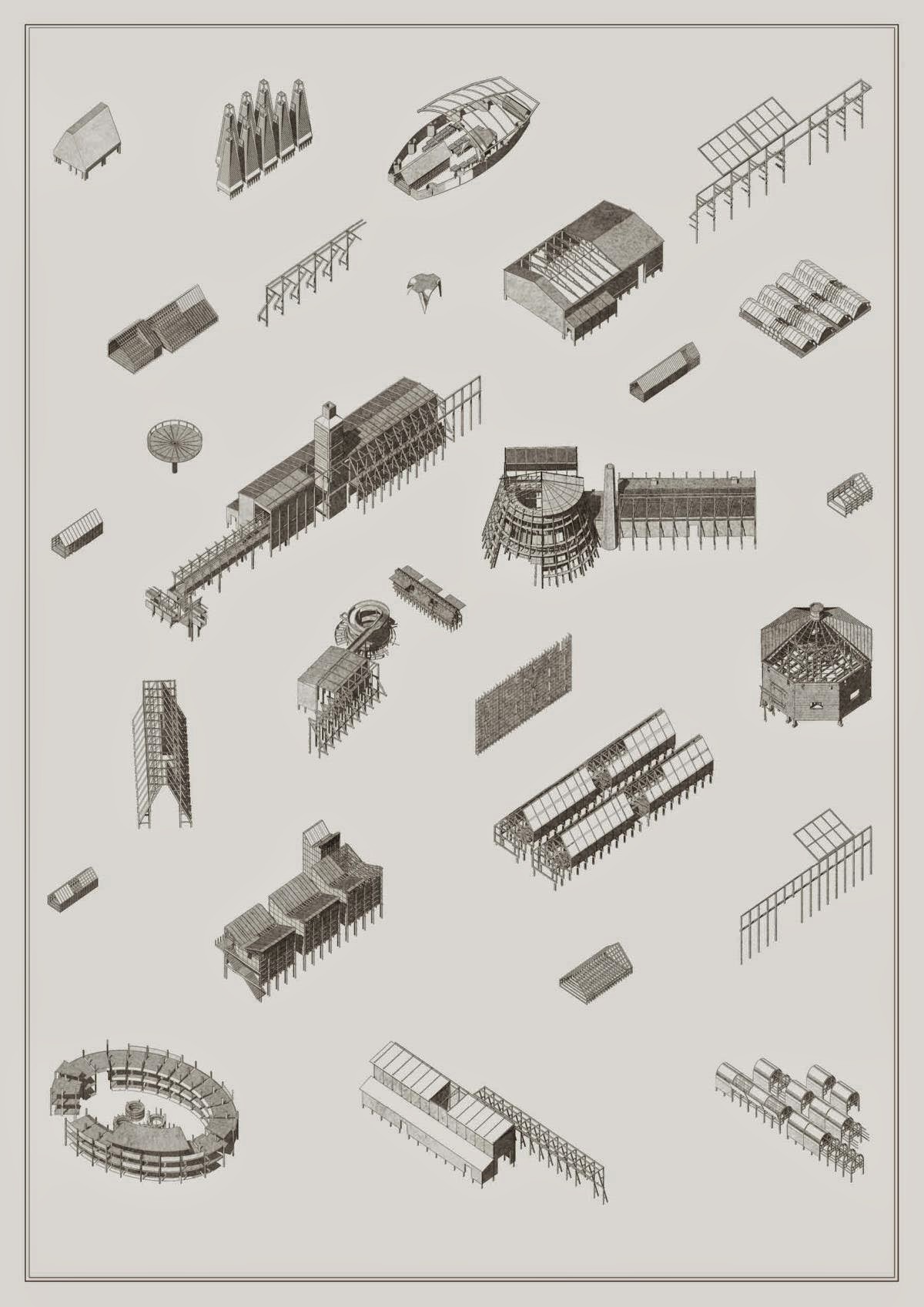

The buildings as a whole are broken down tectonically and typologically, then further analyzed in their own posters.

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

There is, for example, the “slaughterhouse & eating quarters” building, complete with in-house “whole animal butcher shop,” seen here—

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

—as well as the “slow fish market” mentioned earlier.

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

Most of these use exposed timber framing to imply a kind of unfinished or incompletely renovated condition, but these skeletal grids also work to extend the building interiors out along walking paths and brise-soleils, partially outdoor spaces where food and drink could be consumed.

These next few images are absurdly tiny here but can be seen at a larger size over at the President’s Medals; they depict the stabilized facades of the homes on Admirals Row, including how they might change over time.

[Images: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Images: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

Part of this would include the installation of a “raised tunnel network,” effectively just a series of covered walkways and pedestrian viaducts between buildings, offering a visual tour through unrenovated sections of the site but also knitting the overall market together as a whole.

[Images: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Images: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

In any case, I really just think the images are awesome and wanted to post them; sure, the project uses a throwback, sepia-toned, posterization of what is basically just a shopping center to communicates its central point, but the visual style is actually an excellent fit for the proposal and it also seems perfectly pitched to catch the eye of historically minded developers.

You could imagine Anthony Bourdain, for example, enjoying the sight of this for his own forthcoming NY food market.

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

[Image: From “Brooklyn Co-operative” by Yannis Halkiopoulos, University of Westminster; courtesy RIBA President’s Medals].

In a sense, it’s actually too bad this didn’t cross their desks; personally, I wouldn’t mind hopping on the subway for a quick trip to the Navy Yard, to wander around the revitalized ruins, now filled with food stalls and fish mongers, walking through gardens or stumbling brewery to brewery on a Saturday night, hanging out with friends amidst a labyrinth of stabilized industrial buildings, eating fish tacos in the shadow of covered bridges and tunnels passing overhead.

More (and larger) images are available over at the President’s Medals.

Glitches in Spacetime, Frozen into the Built Environment

Back in the summer of 2012, Nicola Twilley and I got to visit the headquarters of GPS, out at Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado.

[Image: Artist’s rendering of a GPS satellite, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Artist’s rendering of a GPS satellite, via Wikipedia].

“Masters of Space”

Over the course of a roughly two-hour visit, we toured, among other things, the highly secure, windowless office room out of which the satellites that control GPS are monitored and operated. Of course, GPS–the Global Positioning System—is a constellation of 32 satellites, and it supplies vital navigational information for everything from smartphones, cars, and construction equipment to intercontinental missiles.

It is “the world’s largest military satellite constellation,” Schriever Air Force Base justifiably boasts.

For somewhat obvious reasons, Nicola and I were not allowed to bring any audio or video recording devices into the facility (although I was able to take notes), and we had to pass through secure checkpoint after secure checkpoint on our way to the actual room. Most memorable was the final door that led to the actual control room: it was on a 15-second emergency response, meaning that, if the door stayed open for more than 15 seconds, an armed SWAT team would arrive to see what was wrong.

When we got inside the actual office space, the lights were quite low and at least one flashing red light reminded everyone inside that civilians were now present; this meant that nothing classified could be discussed. Indeed, if anyone needed to hop on the telephone, they first needed to shout, “Open line!” to make sure that everyone knew not to discuss classified information, lest someone on the other end of the phonecall might hear.

Someone had even made a little JPG for us, welcoming “Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley” to the GPS HQ, and it remained on all the TV monitors while we were there inside the space.

[Image: Transferring control over the GPS constellation. Photo courtesy U.S. Air Force/no photographer given].

[Image: Transferring control over the GPS constellation. Photo courtesy U.S. Air Force/no photographer given].

Surreally, in a room without windows, a group of soldiers who, on the day we visited, were all-male and looked no more than 23 or 24 years old, wore full military camouflage, despite the absence of vegetation to blend into, as they controlled the satellites.

At one point, a soldier began uploading new instructions to the satellites, and we watched and listened as one of those artificial stars assumed its new place in the firmament. What would Giordano Bruno have made of such a place?

This was the room behind the curtain, so to speak, a secure office out of which our nation’s surrogate astronomy is maintained and guided.

Appropriately, they call themselves “Masters of Space.”

[Image: A “Master of Space” badge from Schriever Air Force Base].

[Image: A “Master of Space” badge from Schriever Air Force Base].

In any case, I mention all this for at least two reasons:

A 50,000km-Wide Dark Matter Detector

Edge to edge, the GPS constellation can apparently be considered something of a single device, a massive super-detector whose “time glitches” could be analyzed for signs of dark matter.

As New Scientist explained last month, “The network of satellites is about 50,000 kilometers in diameter, and is traveling through space—along with the entire solar system—at about 300 kilometers a second. So any time shift when the solar system passes through a cosmic kink will take a maximum of 170 seconds to move across network.”

The temporal distortion—a kind of spacetime wave—would propagate across the constellation, taking as long as 170 seconds to pass from one side to the other, leaving forensically visible traces in GPS’s navigational timestamps.

The very idea of a 50,000-kilometer wide super-device barreling through “cosmic kinks” in spacetime is already mind-bogglingly awesome, but add to this the fact that the “device” is actually an artificial constellation run by the U.S. military, and it’s as if we are all living inside an immersive, semi-weaponized, three-dimensional spacetime instrument, sloshing back and forth with 170-second-long tides of darkness, the black ropes of spacetime being strummed by the edges of a 32-point star.

Even better, those same cosmic kinks could theoretically show up as otherwise imperceptible moments of locational error on your own smartphone. This would thus enlist you, against your knowledge, as a minor relay point in a dark matter detector larger than the planet Earth.

The Architectural Effects of Space Weather

While Nicola and I were out at the GPS headquarters in Colorado, one of the custodians of the constellation took us aside to talk about all the various uses of the navigational information being generated by the satellites—including, he pointed out, how they worked to mitigate or avoid errors.

Here, he specifically mentioned the risk of space weather affecting the accuracy of GPS—that is, things like solar flares and other solar magnetic events. These can throw-off the artificial stars of the GPS constellation, leading to temporarily inaccurate location data—which can then mislead our construction equipment here on Earth, even if only by a factor of millimeters.

What’s so interesting and provocative about this is that these tiny errors created by space weather risk becoming permanently inscribed into the built environment—or fossilized there, in a sense, due to the reliance of today’s construction equipment on these fragile signals from space.

That 5mm shift in height from one pillar to the next would thus be no mere construction error: it would be architectural evidence for a magnetic storm on the sun.

Take the Millau Viaduct—just one random example about which I happen to have seen a construction documentary. That’s the massive and quite beautiful bridge designed by Foster + Partners, constructed in France.

[Image: The Millau Viaduct, courtesy of Foster + Partners].

[Image: The Millau Viaduct, courtesy of Foster + Partners].

The precision required by the bridge made GPS-based location data indispensable to the construction process: “Altimetric checks by GPS ensured a precision of the order of 5mm in both X and Y directions,” we read in this PDF.

But even—or perhaps especially—this level of precision was vulnerable to the distorting effects of space weather.

Evidence of the Universe

I have always loved this quotation from Earth’s Magnetism in the Age of Sail, by A.R.T. Jonkers:

In 1904 a young American named Andrew Ellicott Douglass started to collect tree specimens. He was not seeking a pastime to fill his hours of leisure; his motivation was purely professional. Yet he was not employed by any forestry department or timber company, and he was neither a gardener not a botanist. For decades he continued to amass chunks of wood, all because of a lingering suspicion that a tree’s bark was shielding more than sap and cellulose. He was not interested in termites, or fungal parasites, or extracting new medicine from plants. Douglass was an astronomer, and he was searching for evidence of sunspots.

Imagine doing the same thing as Andrew Ellicott Douglass, but, instead of collecting tree rings, you perform an ultra-precise analysis of modern megastructures that were built using machines guided by GPS.

You’re not looking for lost details of architectural history. You’re looking for evidence of space weather inadvertently preserved in titanic structures such as the Millau Viaduct.

[Image: The Millau Viaduct, courtesy of Foster + Partners].

[Image: The Millau Viaduct, courtesy of Foster + Partners].

Fossils of Spacetime

If you take all of this to its logical conclusion, you could argue that, hidden in the tiniest spatial glitches of the built environment, there is evidence not only of space weather but even potentially of the solar system’s passage through “kinks” and other “topological defects” of dark matter, brief stutters of the universe now fossilized in the steel and concrete of super-projects like bridges and dams.

New Scientist points out that a physicist named Andrei Derevianko, from the University of Nevada at Reno, is “already mining 15 years’ worth of GPS timing data for dark matter’s fingerprints,” hoping to prove that GPS errors do, indeed, reveal a deeper, invisible layer of the universe—but how incredibly interesting would it be if, somehow, this same data could be lifted from the built environment itself, secretly found there, inscribed in the imprecisions of construction equipment, perhaps detectable even in the locational drift as revealed by art projects like the Satellite Lamps of Einar Sneve Martinussen, Jørn Knutsen, and Timo Arnall?

The bigger the project, the more likely its GPS errors could be read or made visible—where unexpected curves, glitches, changes in height, or other minor inaccuracies are not just frustrating imperfections caused by inattentive construction engineers, but are actually evidence of spacetime itself, of all the bulging defects and distortions through which our planet must constantly pass now frozen into the built environment all around us.

(Very vaguely related: One of my personal favorite stories here, The Planetary Super-Surface of San Bernardino County).

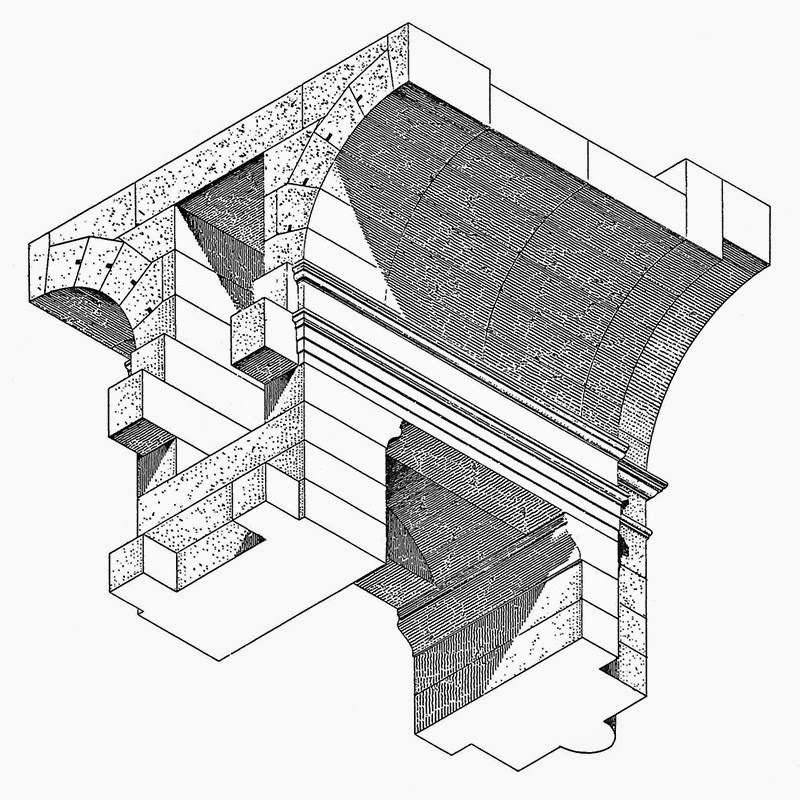

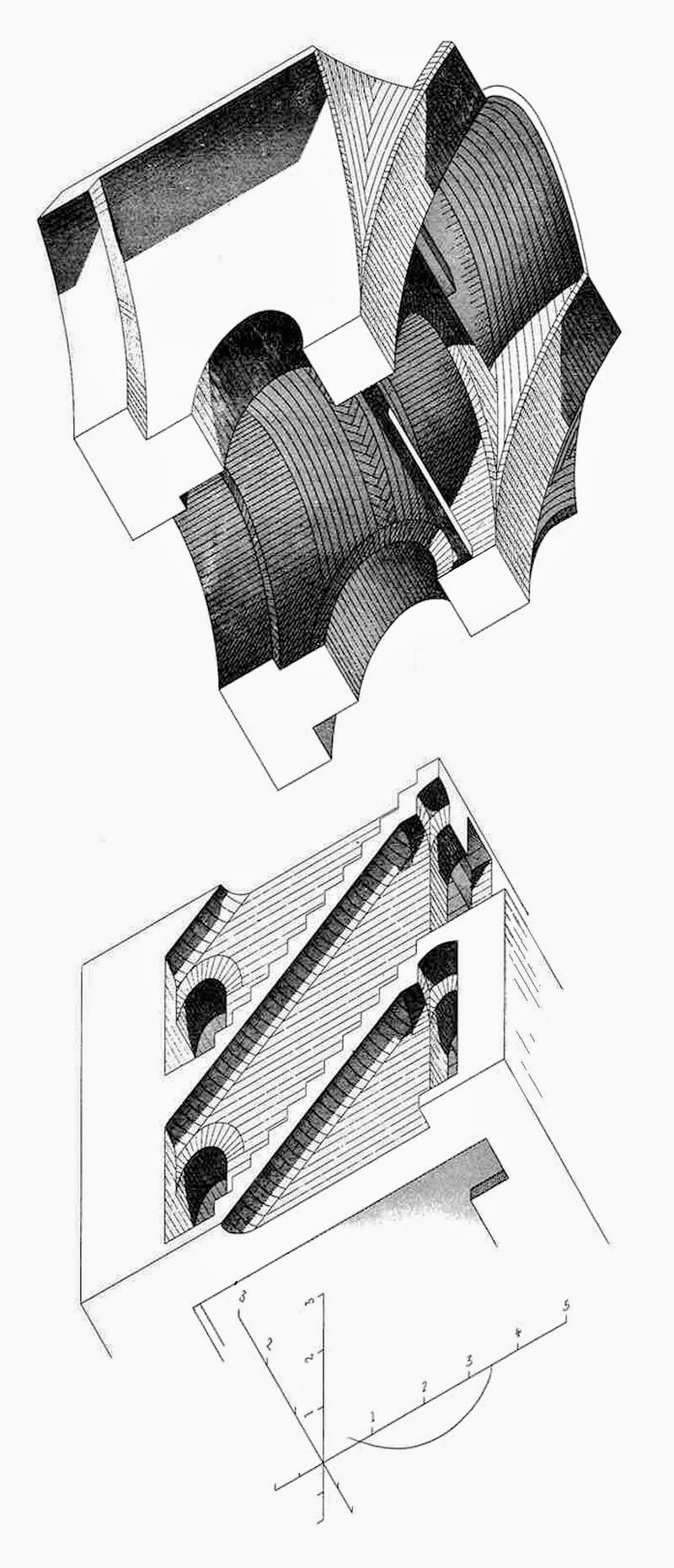

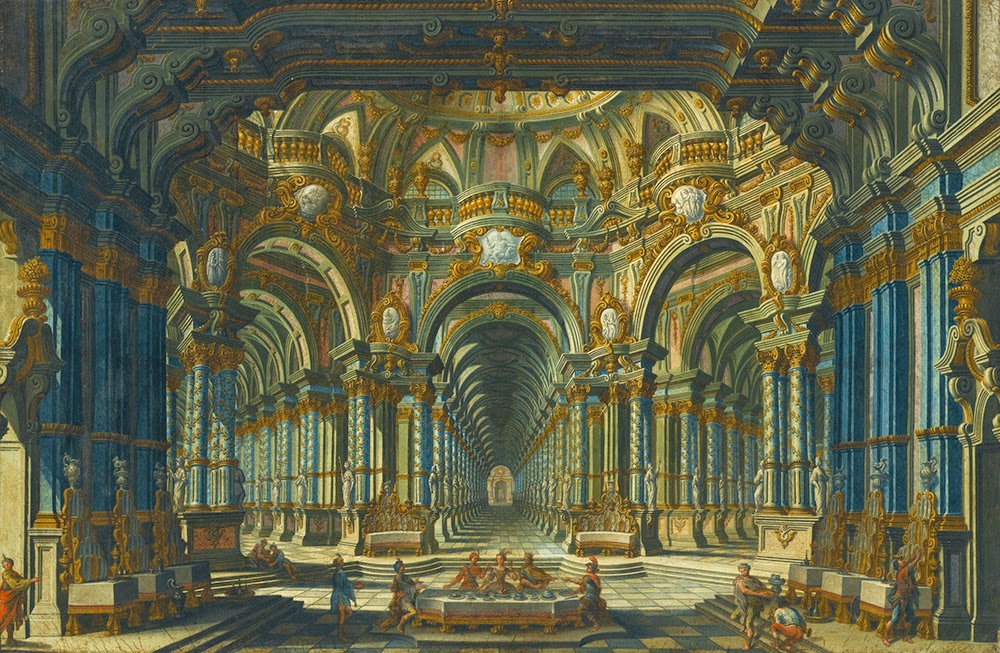

The Neurological Side-Effects of 3D

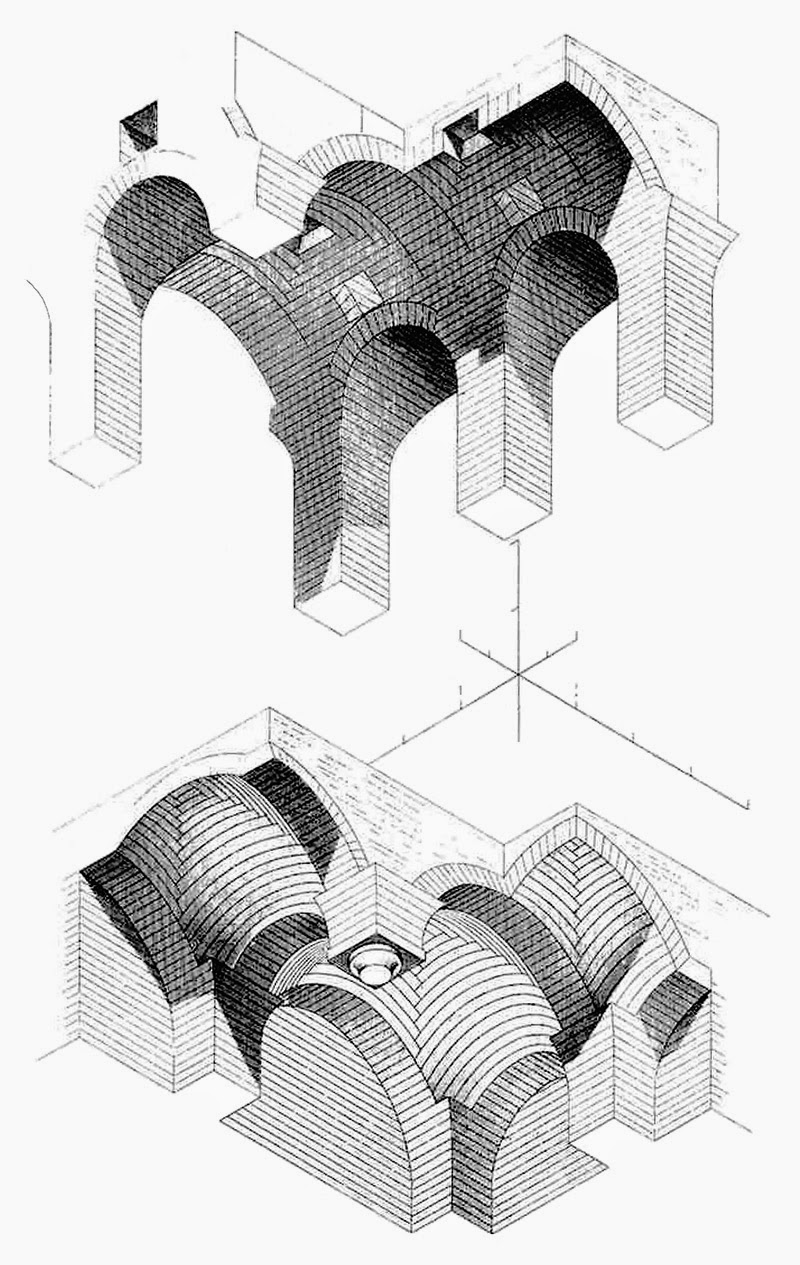

[Image: Auguste Choisy].

[Image: Auguste Choisy].

France is considering a ban on stereoscopic viewing equipment—i.e. 3D films and game environments—for children, due to “the possible [negative] effect of 3D viewing on the developing visual system.”

As a new paper suggests, the use of these representational technologies is “not recommended for chidren under the age of six” and only “in moderation for those under the age of 13.”

There is very little evidence to back up the ban, however. As Martin Banks, a professor of vision science at UC Berkeley, points out in a short piece for New Scientist, “there is no published research, new or old, showing evidence of adverse effects from watching 3D content other than the short-term discomfort that can be experienced by children and adults alike. Despite several years of people viewing 3D content, there are no reports of long-term adverse effects at any age. On that basis alone, it seems rash to recommend these age-related bans and restrictions.”

Nonetheless, he adds, there is be a slight possibility that 3D technologies could have undesirable neuro-physical effects on infants:

The human visual system changes significantly during infancy, particularly the brain circuits that are intimately involved in perceiving the enhanced depth associated with 3D viewing technology. Development of this system slows during early childhood, but it is still changing in subtle ways into adolescence. What’s more, the visual experience an infant or young child receives affects the development of binocular circuits. These observations mean that there should be careful monitoring of how the new technology affects young children.

But not necessarily an outright ban.

In other words, overly early—or quantitatively excessive—exposure to artificially 3-dimensional objects and environments could be limiting the development of retinal strength and neural circuitry in infants. But no one is actually sure.

What’s interesting about this for me—and what simultaneously inspires a skeptical reaction to the supposed risks involved—is that we are already surrounded by immersive and complexly 3-dimensional spatial environments, built landscapes often complicated by radically diverse and confusing focal lengths. We just call it architecture.

Should the experience of disorienting works of architecture be limited for children under a certain age?

[Image: Another great image by Auguste Choisy].

[Image: Another great image by Auguste Choisy].

It’s not hard to imagine taking this proposed ban to its logical conclusion, claiming that certain 3-dimensionally challenging works of architectural space should not be experienced by children younger than a certain age.

Taking a cue from roller coasters and other amusement park rides considered unsuitable for people with heart conditions, buildings might come with warning signs: Children under the age of six are not neurologically equipped to experience the following sequence of rooms. Parents are advised to prevent their entry.

It’s fascinating to think that, due to the potential neurological effects of the built environment, whole styles of architecture might have to be reserved for older visitors, like an X-rated film. You’re not old enough yet, the guard says patronizingly, worried that certain aspects of the building will literally blow your mind.

Think of it as a Schedule 1 controlled space.

[Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of Sotheby’s].

[Image: From the Circle of Francesco Galli Bibiena, “A Capriccio of an Elaborately Decorated Palace Interior with Figures Banqueting, The Cornices Showing Scenes from Mythology,” courtest of Sotheby’s].

Or maybe this means that architecture could be turned into something like a new training regimen, as if you must graduate up a level before you are able to handle specific architectural combinations, like conflicting lines of perspective, unreal implications of depth, disorienting shadowplay, delayed echoes, anamorphic reflections, and other psychologically destabilizing spatial experiences.

Like some weird coming-of-age ceremony developed by a Baroque secret society overly influenced by science fiction, interested mentors watch every second as you and other trainees react to a specific sequence of architectural spaces, waiting to see which room—which hallway, which courtyard, which architectural detail—makes you crack.

Gifted with a finely honed sense of balance, however, you progress through them all—only to learn at the end that there are four further buildings, structures designed and assembled in complete secrecy, that only fifteen people on earth have ever experienced. Of those fifteen, three suffered attacks of amnesia within a year.

Those buildings’ locations are never divulged and you are never told what to prepare for inside of them—what it is about their rooms that makes them so neurologically complex—but you are advised to study nothing but optical illusions for the next six months.

[Image: One more by Auguste Choisy].

[Image: One more by Auguste Choisy].

Of course, you’re told, if it ever becomes too much, you can simply look away, forcing yourself to focus on only one detail at a time before opening yourself back up to the surrounding spatial confusion.

After all, as Banks writes in New Scientist, the discomfort caused by one’s first exposure to 3D-viewing technology simply “dissipates when you stop viewing 3D content. Interestingly, the discomfort is known to be greater in adolescents and young adults than in middle-aged and elderly adults.”

So what do you think—could (or should?) certain works of architecture ever be banned for neurologically damaging children under a certain age? Is there any evidence that spatially disorienting children’s rooms or cribs have the same effect as 3D glasses?