[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by Rodney Fitch, whose later motto was “Shopping is the Purpose of Life.” I don’t otherwise have any info about the school; image found via aqqindex].

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by Rodney Fitch, whose later motto was “Shopping is the Purpose of Life.” I don’t otherwise have any info about the school; image found via aqqindex].

Tag: Modular

Speleological Superparks

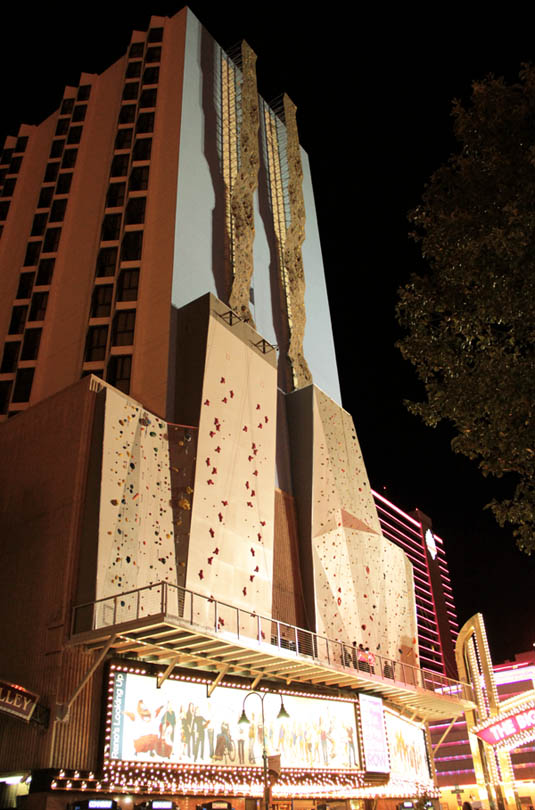

[Image: Downtown Reno on a Saturday night with people queuing up to climb the BaseCamp wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Downtown Reno on a Saturday night with people queuing up to climb the BaseCamp wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

As part of an overall strategy to rebrand itself not as a city of gambling and slot machines—not another Las Vegas—but as more of a gateway to outdoor sports and adventure tourism—a kind of second Boulder or new Moab—Reno, Nevada, now houses the world’s largest climbing wall, called BaseCamp, attached to the side of an old hotel.

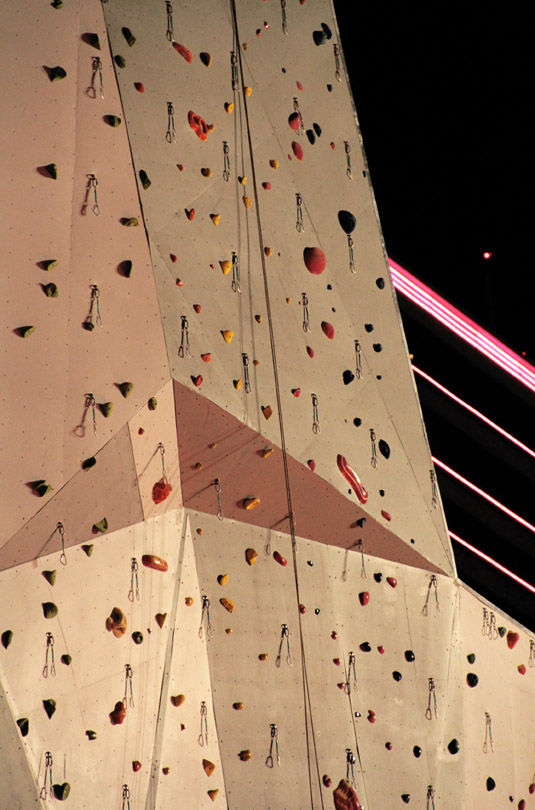

[Image: The wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

BaseCamp is “a 164-foot climbing wall, 40 feet taller than the previous world’s highest in the Netherlands,” according to DPM Climbing. “The bouldering area will also be world-class with 2900 square feet of overhanging bouldering surface.”

You can see a few pictures of those artificial boulders over at DPM.

[Image: The wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The wall; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Fascinatingly, though, the same company who designed and manufactured this installation—a firm called Entre Prises—also makes artificial caves.

One such cave, in particular, created for and donated to the British Caving Association, is currently being used “to promote caving at shows and events around the country. It is now housed in its own convenient trailer and is available for use by Member Clubs and organizations.”

[Image: The British Caving Association’s artificial cave, designed by Entre Prises; photo by David Cooke].

[Image: The British Caving Association’s artificial cave, designed by Entre Prises; photo by David Cooke].

These replicant geological forms are modular, easily assembled, and come in indoor and outdoor varieties. Indoor artificial caves, we read, “are usually made from polyester resin and glass fibre as spraying concrete indoors is often not very practicable. Indoor caves provide the experience of caving without some of the discomforts of natural or outdoor caves: the air temperature can be relatively easily controlled, in most cases specialist clothing is not required [and] the passage walls are not very thick so more cave passage can be designed to go into a small area.”

Further, maintaining the exclamation point from the original text: “The modular nature of the Speleo System makes it possible to create any cave type and can be modified in minutes by simply unbolting and rotating a section! This means you can have hundreds of possible caving challenges and configurations for the price of one.”

It would be interesting to live in a city, at least for a few weeks, ruled by an insane urban zoning board who require all new buildings—both residential and commercial—to include elaborate artificial caves. Not elevator shafts or emergency fire exits or public playgrounds: huge fake caves torquing around and coiling through the metropolis. Caves that can be joined across property lines; caves that snake underneath and around buildings; caves that arch across corporate business lobbies in fern-like sprays of connected chambers. Plug-in caves that tour the city in the back of delivery trucks, waiting to be bolted onto existing networks elsewhere. From Instant City to Instant Cave. Elevator-car caves that arrive on your floor when you need them. Caves on hovercrafts and helicopters, detached from the very earth they attempt to represent.

This brings to mind the work of Carsten Höller, implying a project someday in which the Turbine Hall in London’s Tate Modern could be transformed into the world’s largest artificial cave system, or perhaps even a future speleo-superpark in a place like Dubai, where literally acres of tunnels sprawl across the landscape, inside and outside, aboveground and below ground, in unpredictably claustrophobic rearrangeable prefab whorls.

The “outdoor” varieties, meanwhile, are actually able “to be buried within a hillside”; however, they “must be able to withstand the bearing pressure of any overlying material, eg. soil or snow. This is usually addressed by making the caving structures in sprayed concrete that has been specifically engineered to withstand the loads. Alternatively the cave passages can be constructed in polyester resin and glass fibre but then they have to be within a structural ‘box’ if soil pressure is to be applied.”

In any case, here are some of the cave modules offered by Entre Prises, a kind of cave catalog called the Speleo System—though it’s worth noting, as well, that “To add interest within passages and chambers, cave paintings and fossils can be added. This allows for user interest to be maintained, creating an educational experience.”

[Image: The Speleo System by Entre Prises].

[Image: The Speleo System by Entre Prises].

As it happens, Entre Prises is also in the field of ice architecture. That is, they design and build large, artificially maintained ice-climbing walls.

These “artificial ice climbing structures… support natural ice where the air temperature is below freezing point.” However, “permanent indoor structures,” given “a temperature controlled environment,” can also be created. These are described as “self generating real ice structures that utilize a liquid nitrogen refrigeration system.”

[Images: An artificial ice structure by Entre Prises for the Winter X Games].

[Images: An artificial ice structure by Entre Prises for the Winter X Games].

Amongst many things, what interests me here is the idea that niche sports enthusiasts—specifically cavers and climbers—have discovered and, perhaps more importantly, financially support a unique type of architecture and the construction techniques required for assembling it that, in an everyday urban context, would appear quite eccentric, if not even avant-garde.

Replicant geological formations in the form of modular, aboveground caves and artificially frozen concrete towers only make architectural and financial sense when coupled with the needs of particular recreational activities. These recreational activities are more like spatial incubators, both inspiring and demanding new, historically unexpected architectural forms.

So we might say that, while architects are busy trying to reimagine traditional building typologies and architectural programs—such as the Library, the Opera House, the Airport, the Private House—these sorts of formally original, though sometimes aesthetically kitsch, designs that we are examining here come not from an architecture firm at all, or from a particular school or department, but from a recreational sports firm pioneering brand new spatial environments.

As such, it would be fascinating to see Entre Prises lead a one-off design studio somewhere, making artificial caves a respectable design typology for students to admit they’re interested in, while simultaneously pushing sports designers to see their work in more architectural terms and prodding architects to see niche athletes as something of an overlooked future clientele.