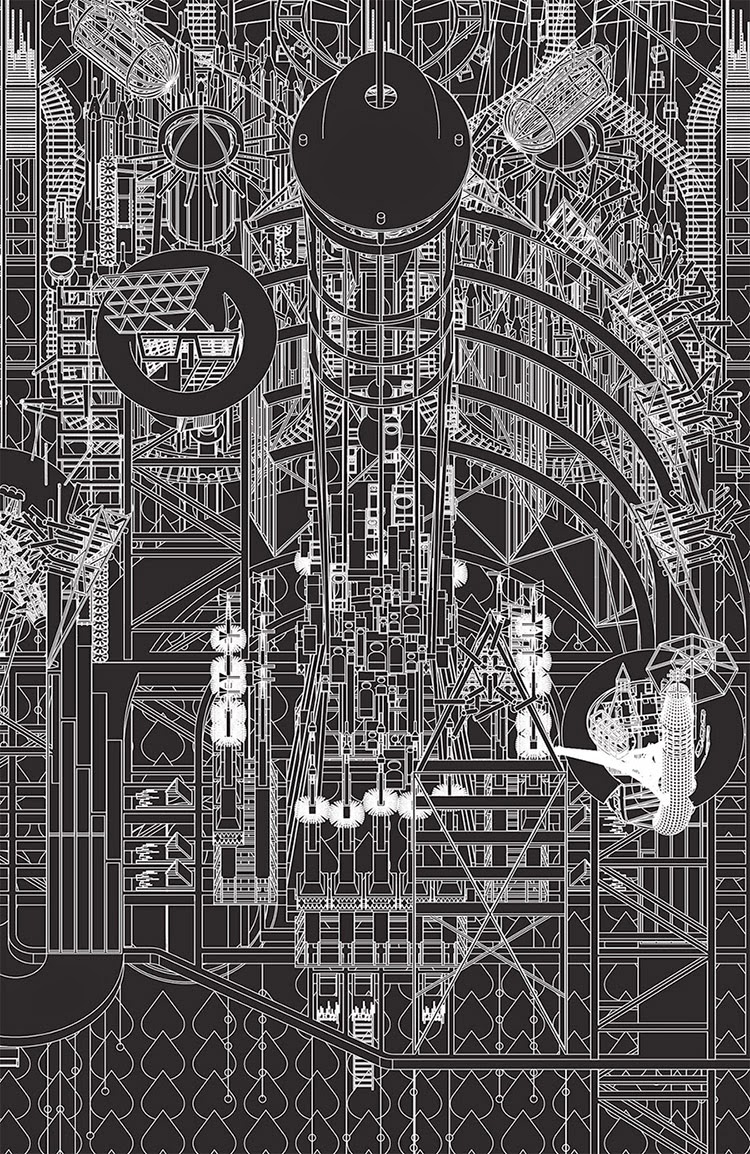

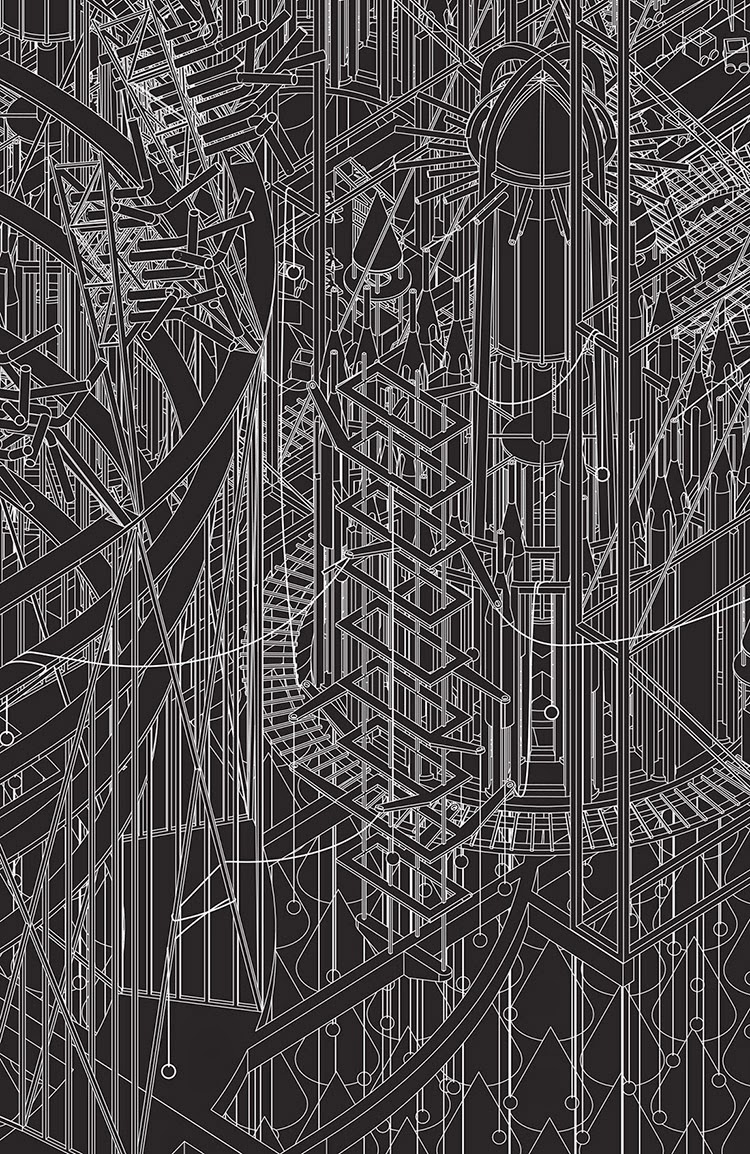

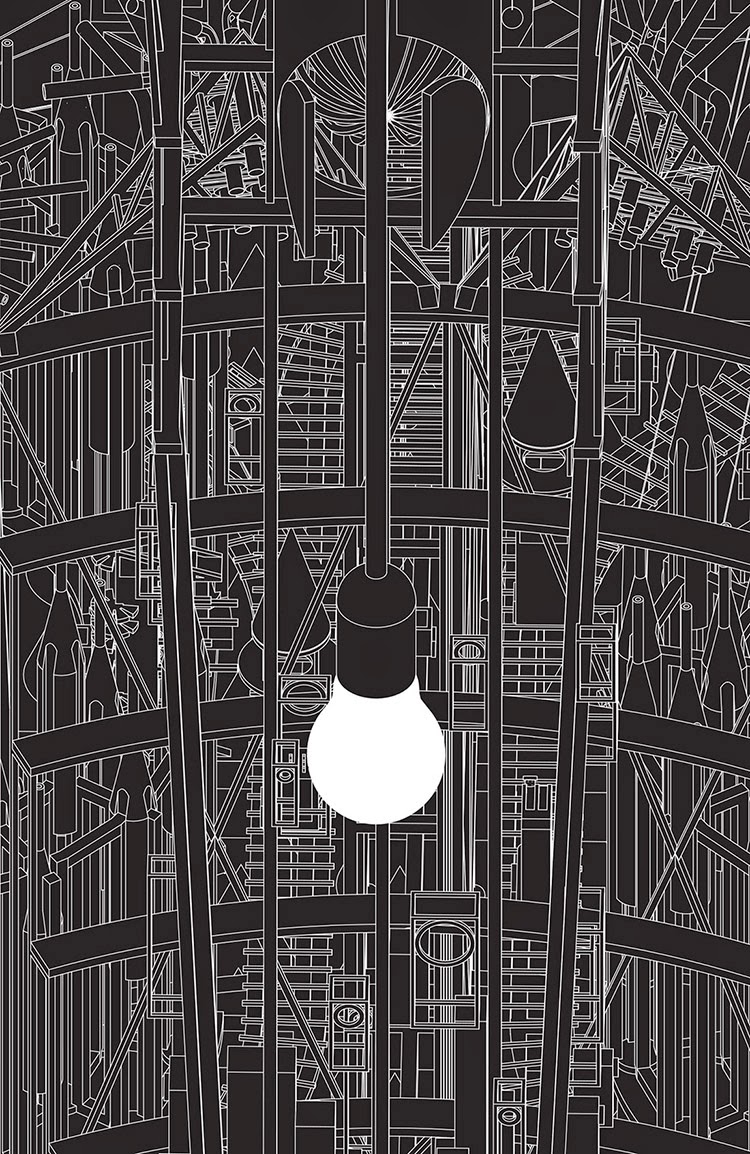

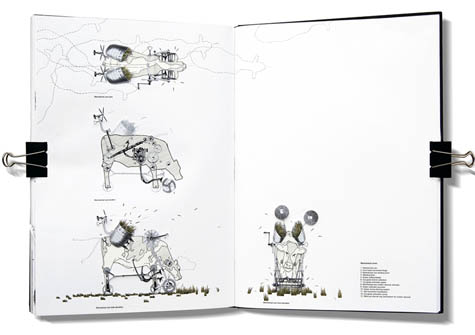

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Later this summer, London’s Flea Folly Architects—Pascal Bronner & Thomas Hillier—will be running a workshop in what they broadly call “narrative architecture” at the Tate Modern.

“What would a town inhabited by Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder and Man Ray look like?” they ask. “Taking inspiration from works in the Tate collection, in particular the speculative etchings by architects Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin and paintings by the Surrealists, our objective is to design and build a fictional miniature village made entirely from paper.”

Their own project, Grimm City, is perhaps an example of what might result.

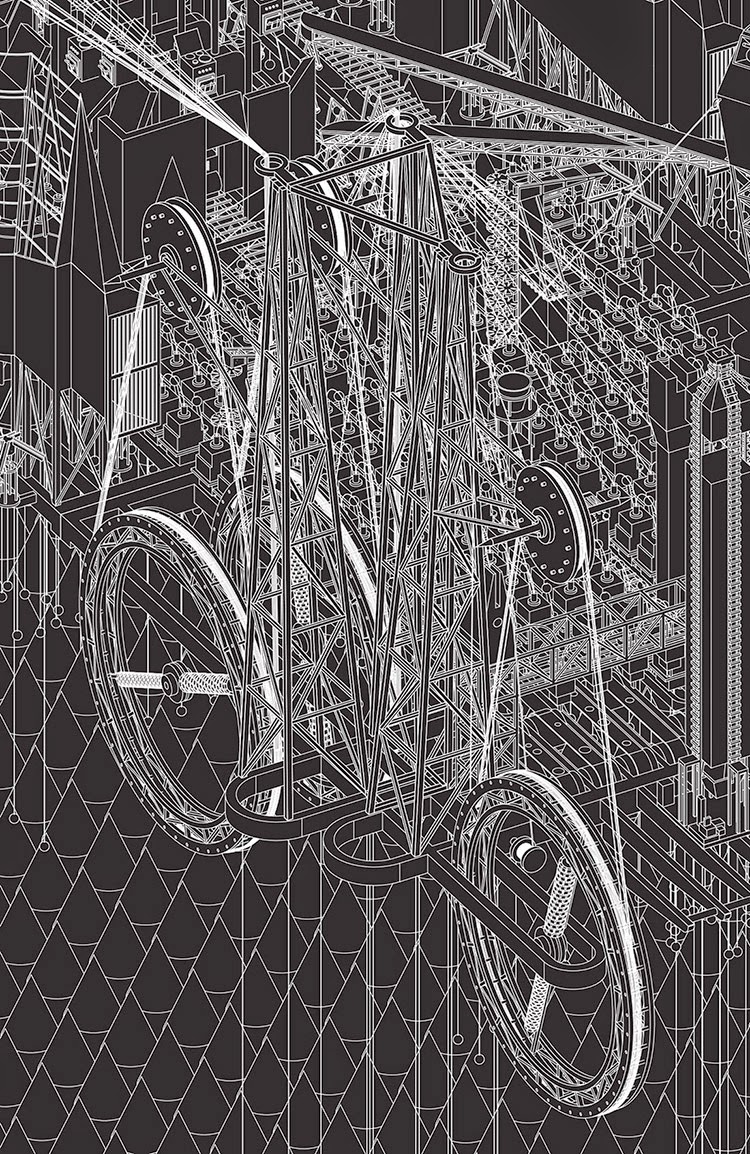

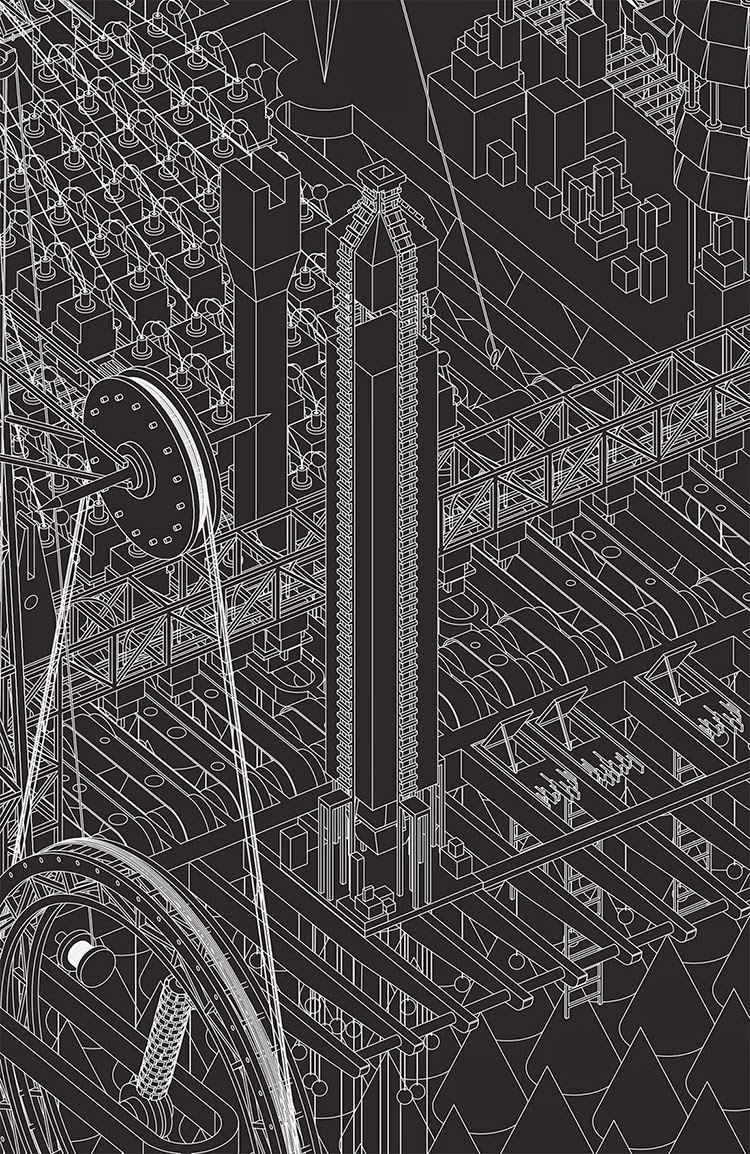

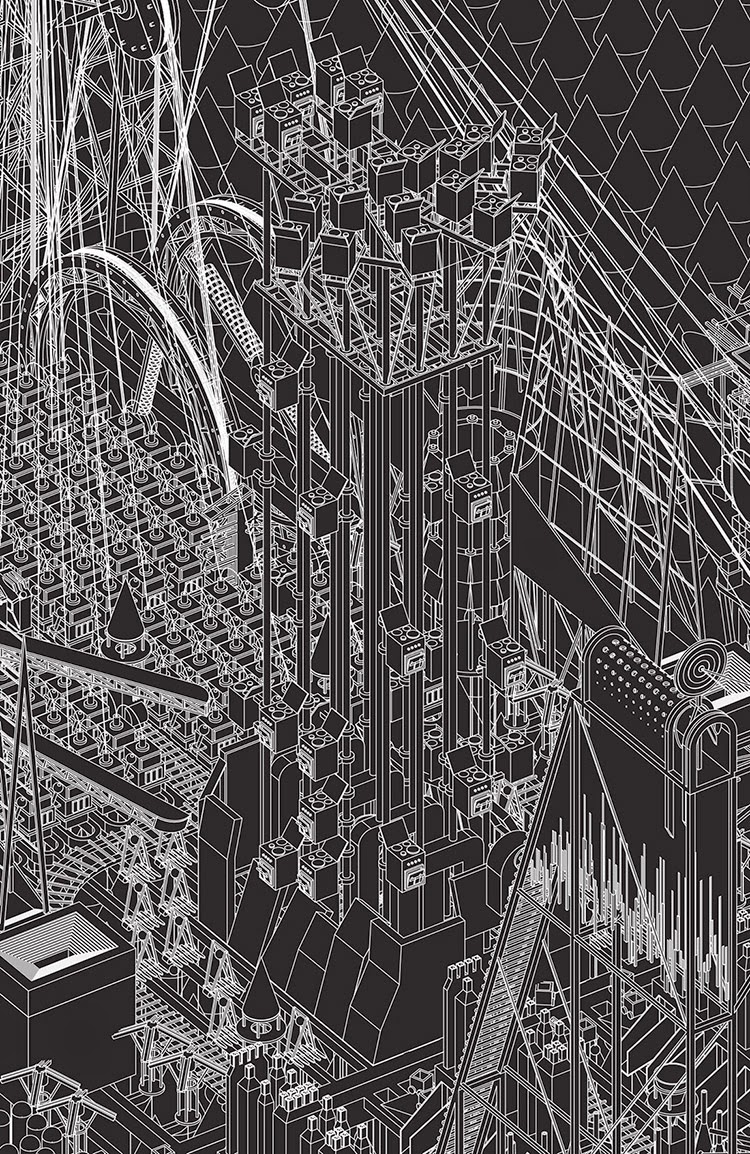

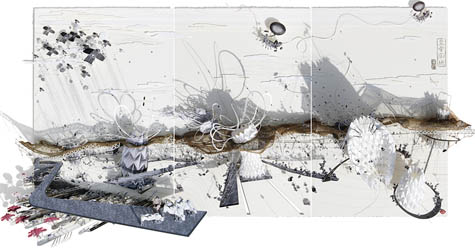

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

As architect CJ Lim describes it in his introduction to the project in a gorgeously produced, limited print-run hardcover catalog, as “Grimm City is a future state derived from architectural extrapolations of the fairytales by the Brothers Grimm.”

That is, it is an elaborate narrative disguised as a city—a story given urban form.

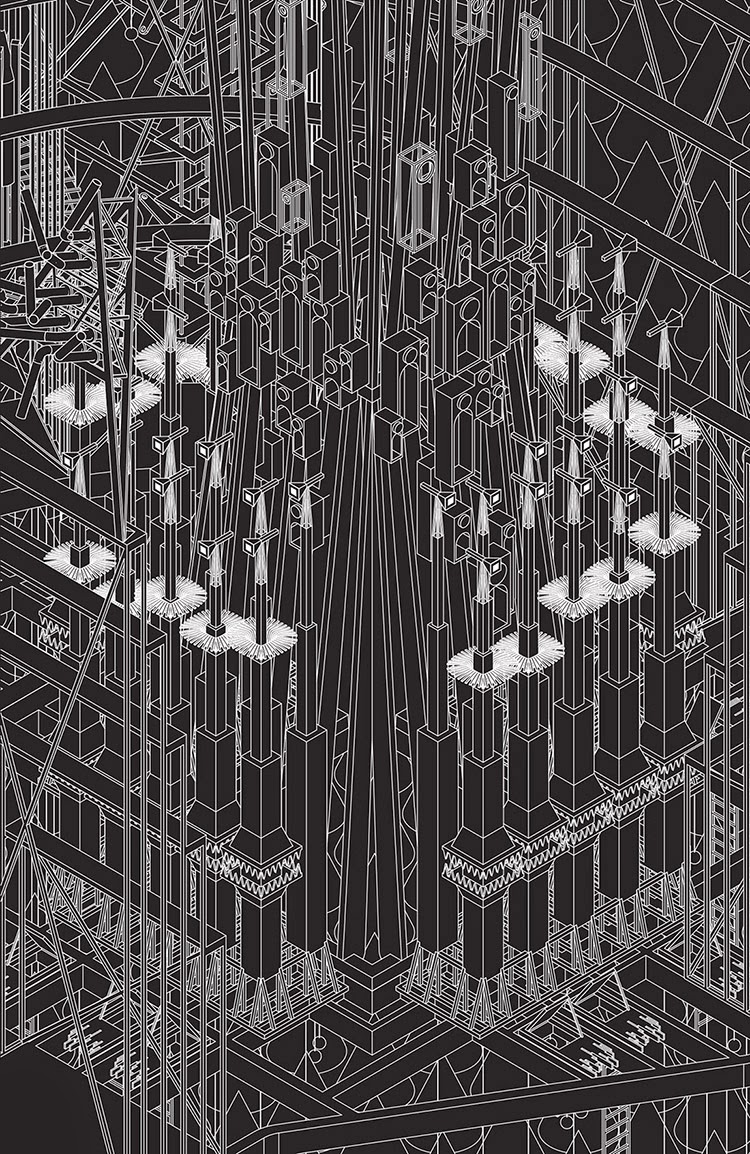

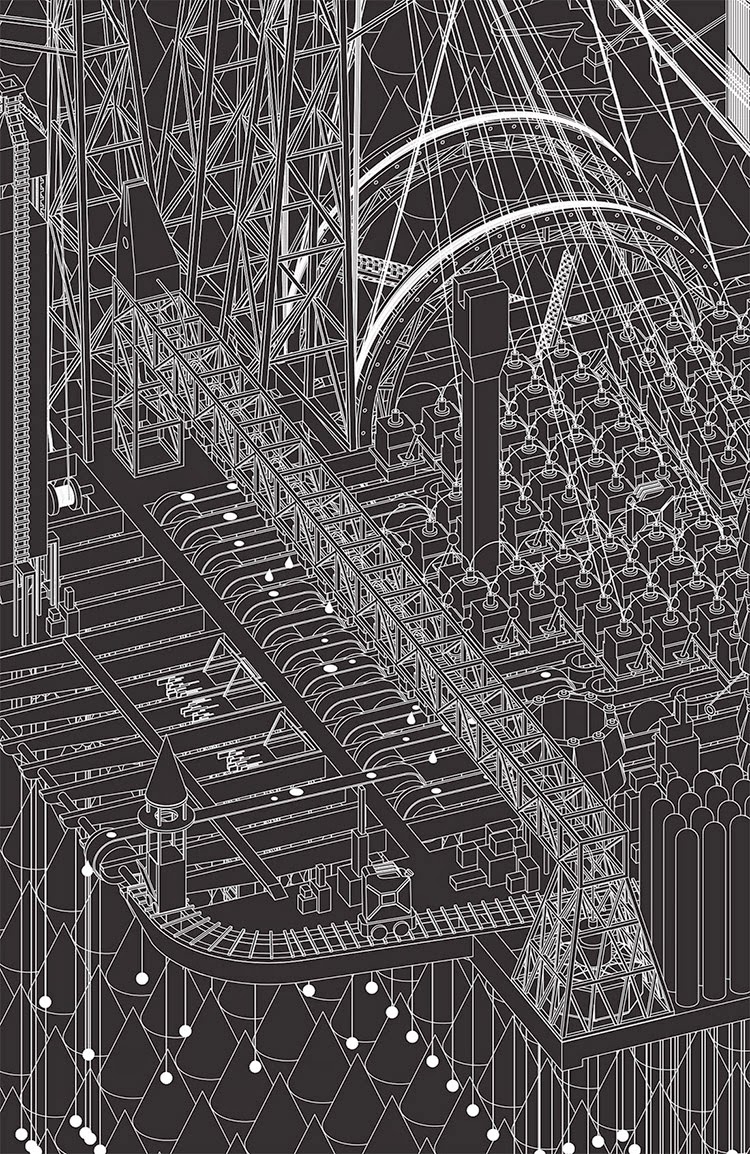

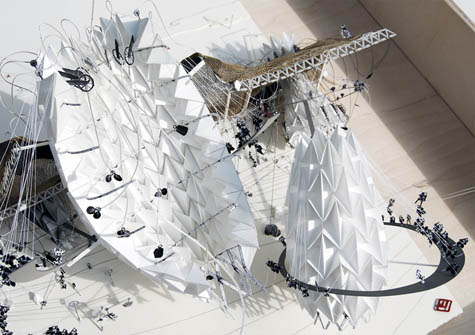

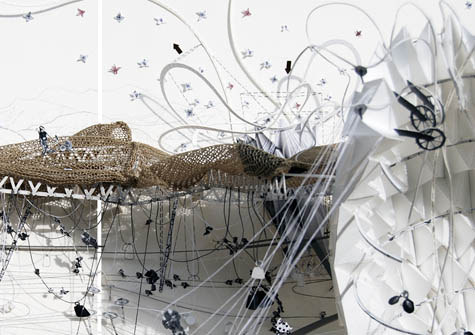

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Bronner and Hillier explain that the “blueprint” for their city was “conceived in ink exactly 200 years ago,” and “was shaped by 86 magnificent tales collected by two of the most distinguished storytellers of their time.”

They are referring, of course, to the Brothers Grimm.

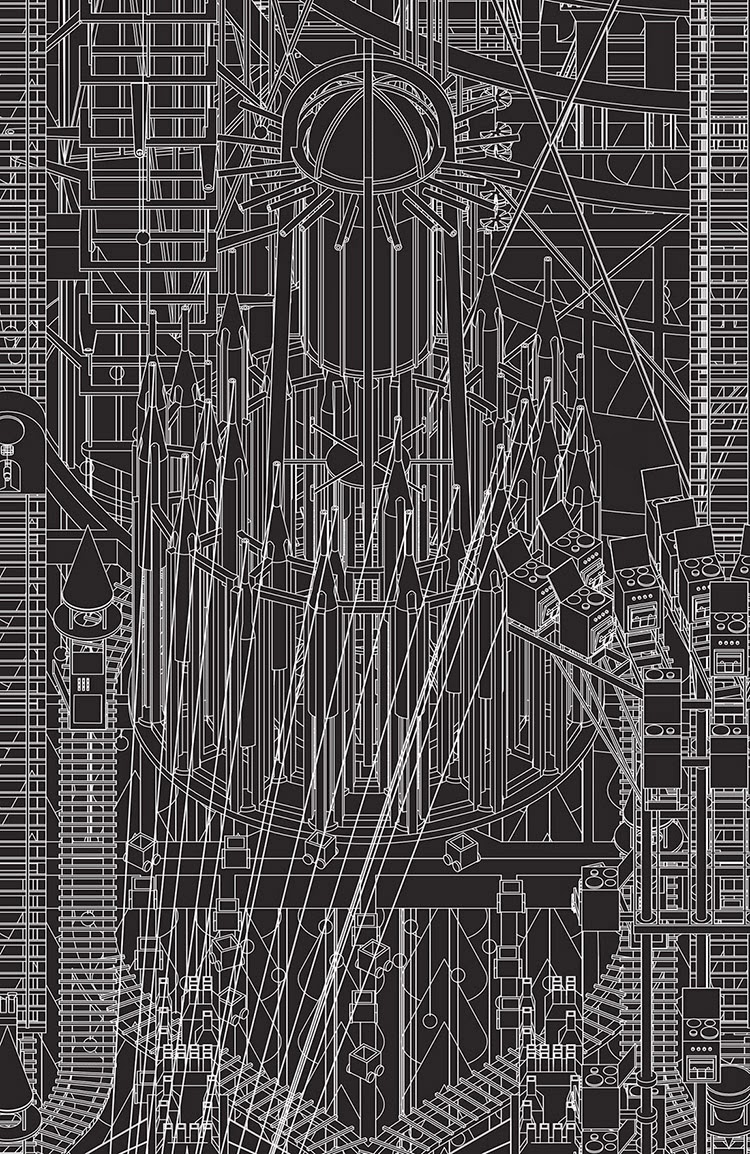

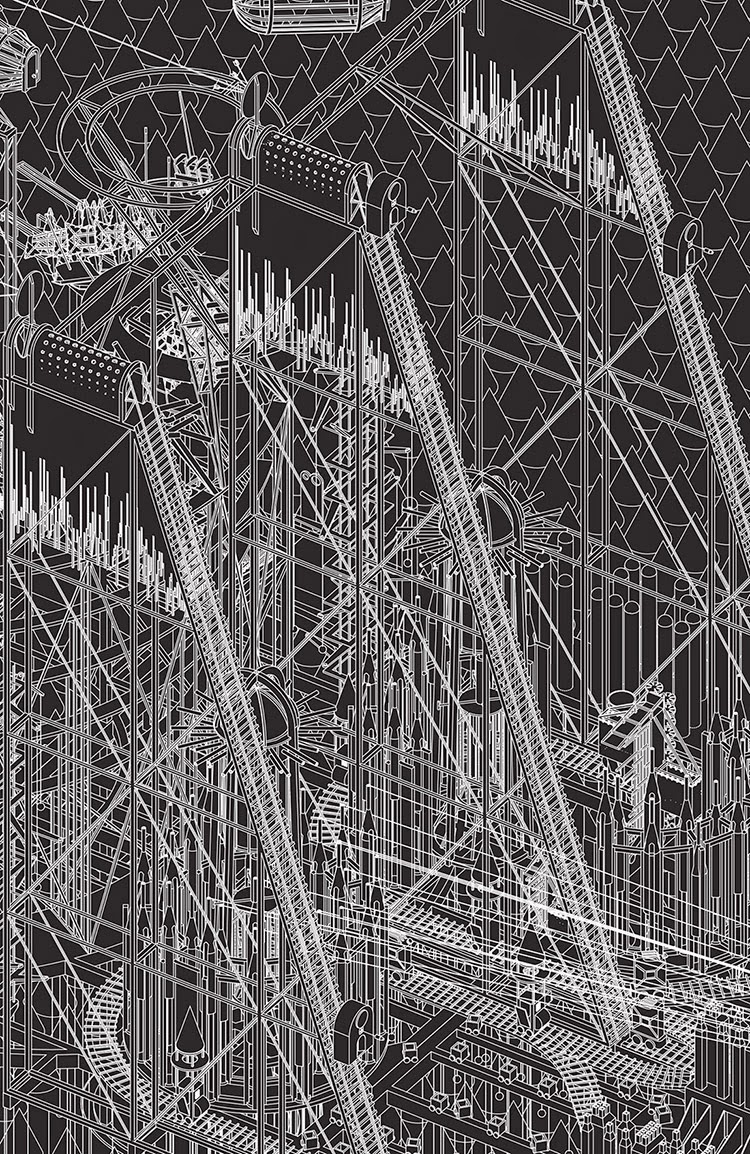

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Briefly, in what now feels like another lifetime, when I was backpacking through Germany after graduating from college, I made a beeline to the small city of Marburg after reading that it was a university town overlooked by an 11th-century fort—and that it was also once home to the Brothers Grimm.

I showed up by train and spent a few days there, mostly reading Grimm stories, feeding ducks, and walking around the roads that spiraled up to the castle; and I later learned, with equal interest, that one of the weird coincidences of history would make Marburg the same city where a strain of hemorrhagic fever would be isolated.

The disease, which is now rather straight-forwardly called Marburg, seems a fittingly strange continuation of the stories of the Brothers Grimm, in terms of the dark and often fatal transformations humans can undergo.

In any case, Grimm City is an architectural translation of their various stories, plots, allegories, and characters, and it took on a life of its own. “With enormous spinning wheels, tower-like limbs and turrets for claws, it began to resemble a machine that had been unjustly woken from its deep slumber,” they write.

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

At times visually reminiscent of Aldo Rossi or even John Hejduk, the black diagrams are unexpectedly carnivalesque, monochromatic yet fizzing with lively detail.

There are structures such as The Ink Factory, a Silver Forest (made entirely of money-producing slot machines, eg. a forest where silver grows), an economic Barometer spinning over the city, and a school of thieves and burglary.

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

There are also banks, churches, and a “windowless monolith” filled with forensic evidence of the city’s crimes.

Then, tacked way at the top of massive stairways so inclined they look like ladders, there are Confession Booths where the city’s sins are meant to be narrated and explained.

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

Your exposure and isolation in ascending to the Booths is part of the process: a confessional infrastructure that compels one toward self-incrimination.

Elsewhere, there’s The Morning Star, a kind of heliogenic megabulb that hangs over the city, casting shadows and making time, burning at the center of an urban calendar that guides the lives of those living in the streets below.

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

And, finally, there is a huge plateau known as The Golden Compound where a vast sprawl—of what appear to be batteries—promises a “commune for the living-dead,” a dormitory those who “cheat death and remain everlasting” in this fairy tale metropolis.

“No one really knows if those inside” of these endless, battery-like structures, “are dead or alive,” we read, “and no one dares to find out.” They could be described as electrical mausoleums where sleeping beauties lie, equally alive and dead.

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by Flea Folly Architects].

There are many, many further images, of course, as well as an intricate physical model that accompanied them; the whole thing was displayed at the London Design Museum back in October-November 2013 and, with any luck, the images and model both will someday show up in a gallery near you.

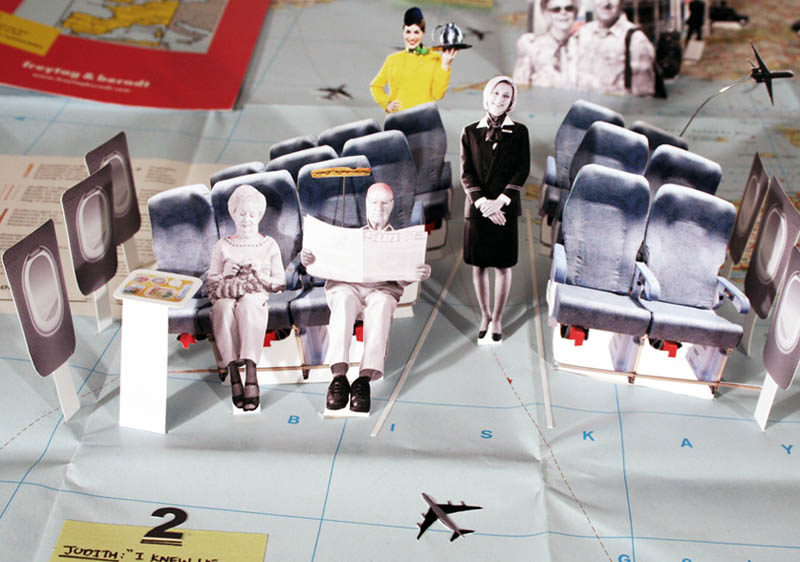

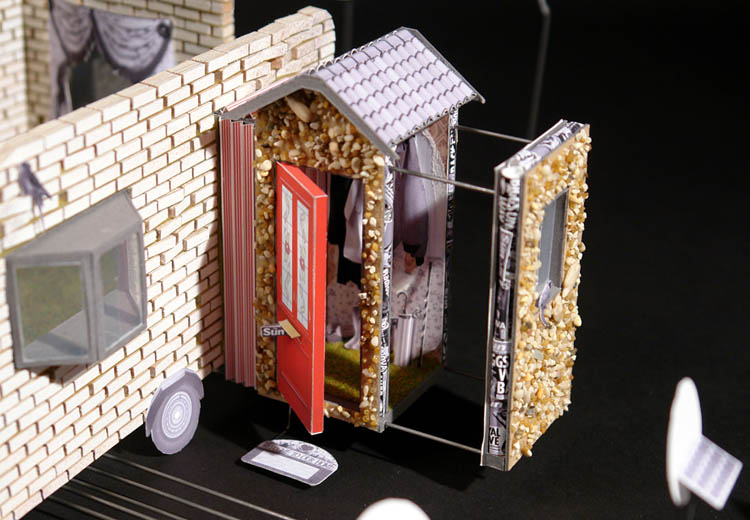

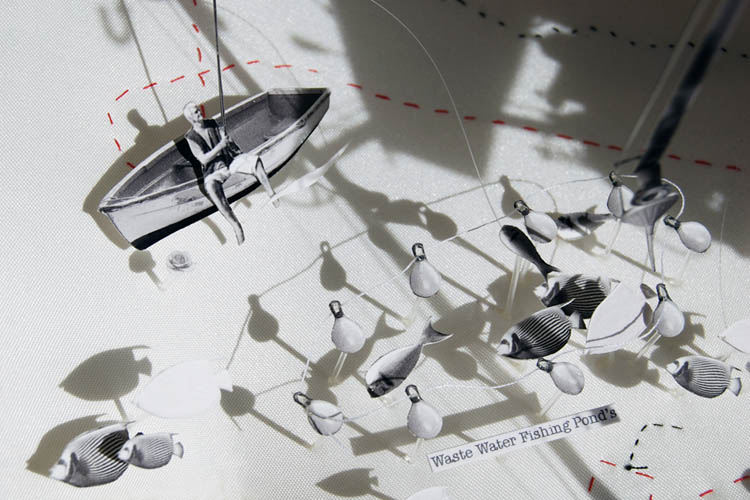

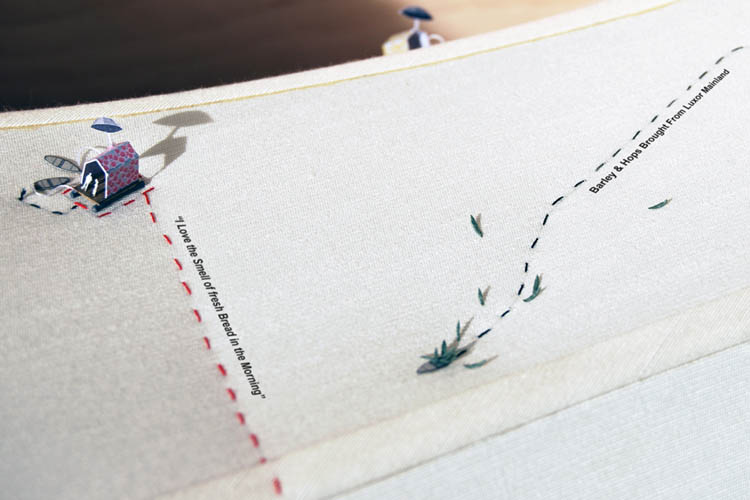

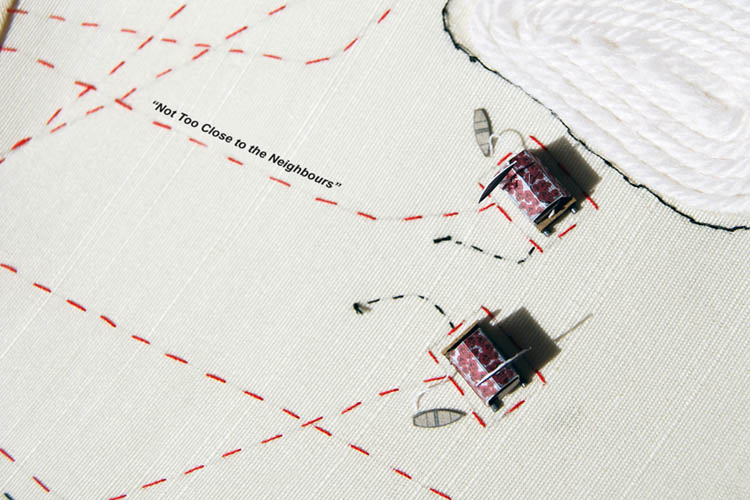

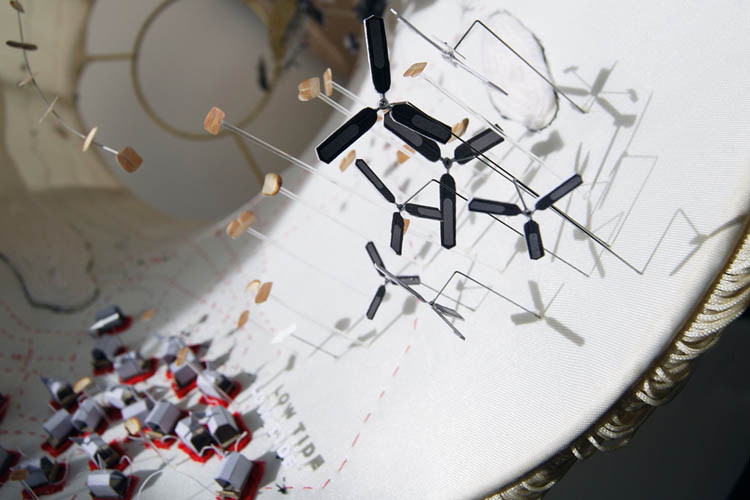

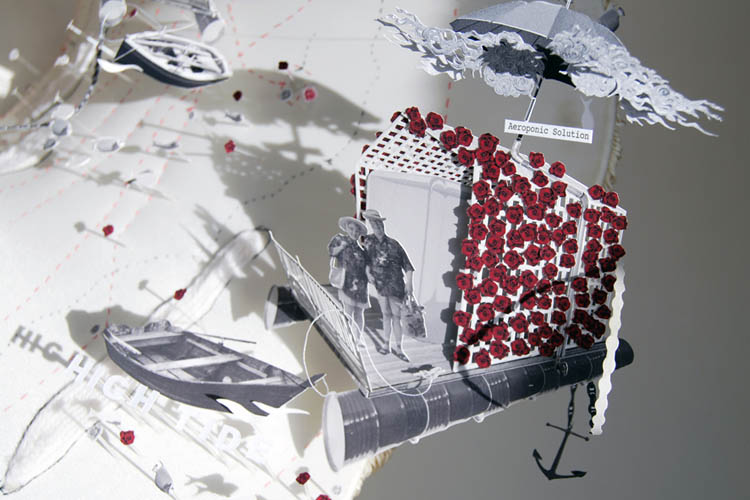

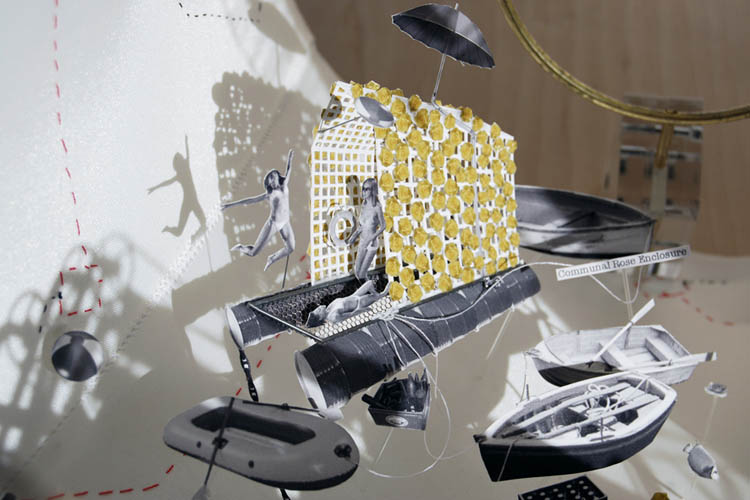

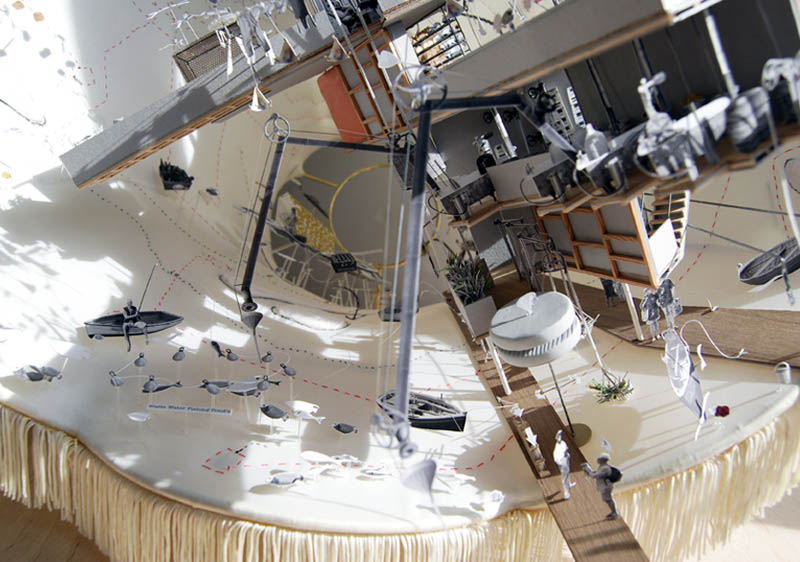

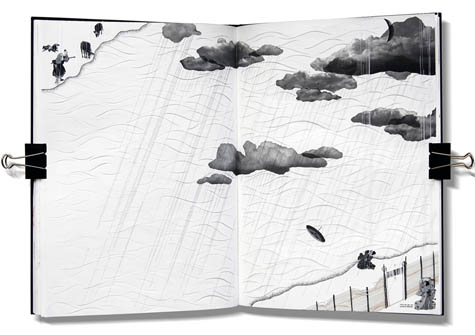

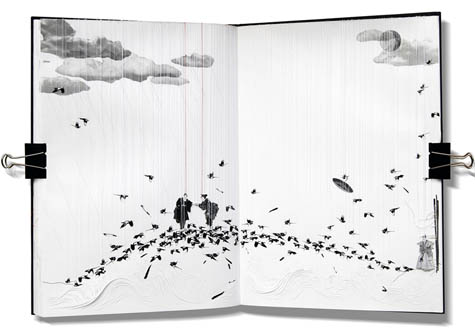

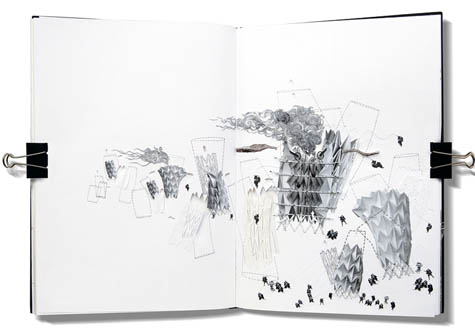

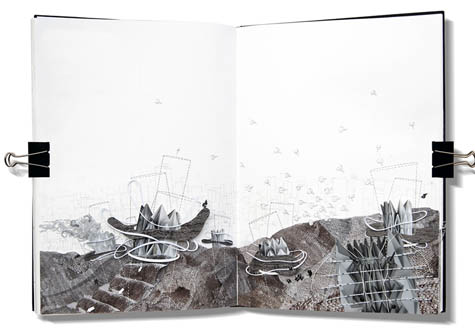

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by  [Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by  [Image: Image 1, “Eternal Punishment,” from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Image: Image 1, “Eternal Punishment,” from The Emperor’s Castle by  [Image: Image 2, “The Last Meeting,” from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Image: Image 2, “The Last Meeting,” from The Emperor’s Castle by

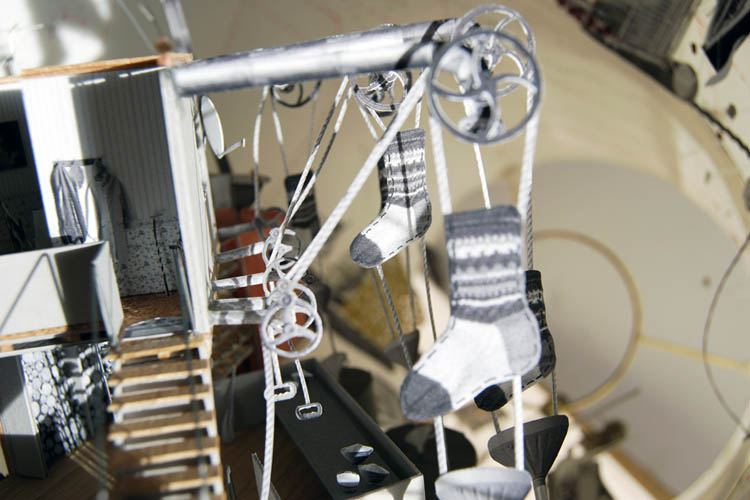

[Images: Image 3, “The Emperor’s Origami Lungs”; Image 4, “The Princess’s Knitted Canopy”; and Image 5, “The Cowherd’s Mechanical Cow-cutters”; from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Images: Image 3, “The Emperor’s Origami Lungs”; Image 4, “The Princess’s Knitted Canopy”; and Image 5, “The Cowherd’s Mechanical Cow-cutters”; from The Emperor’s Castle by  [Image: Image 6 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Image: Image 6 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Images: Images 7, 8, 9, and 10 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Images: Images 7, 8, 9, and 10 from The Emperor’s Castle by  [Image: Image 11 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Image: Image 11 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Images: Images 12, 13, 14, and 15 from The Emperor’s Castle by

[Images: Images 12, 13, 14, and 15 from The Emperor’s Castle by