[Image: “Ringroad (Houston)” (2005) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Ringroad (Houston)” (2005) by Bas Princen].

Photographer Bas Princen has published a new book looking at the visual and personal backstory to one particular photograph, seen above, “Ringroad (Houston),” from 2005. Called The Construction of an Image, the book is also the final publication from Bedford Press.

It is, the book’s editor, Vanessa Norwood, writes, “an arresting image: an ordinary American office block transformed by Princen’s lens into a glowing golden cube cut by the horizon, acting as both mirror and container; the reflected landscape of trees confined within its gridded exterior.”

As part of his work process, Princen assembles small research notebooks of images he is thinking of or influenced by during the production of certain images; The Construction of an Image includes those along with other examples of Princen’s work created at the same time. As such, it offers a sustained glimpse of how Princen operates, how visual concepts are formed, and how analogies are identified and tracked from one building or landscape to another.

In the case of “Ringroad (Houston),” these precedent images range from engravings by Albrecht Dürer—fitting the world into a perspectival grid—to photographs taken inside geodesic domes, and from corporate lobbies to archaeological earthworks. These represent moments or sites where solitary structures, all-encompassing geometric frames or grids, and uneasy distinctions between foreground and background predominate.

I’m proud to have a short essay featured in the book, alongside texts by editor Vanessa Norwood, architect Kersten Geers, curator Moritz Küng, and a summary by Princen himself.

Geers, in particular, swings for the fences with his assessment of the photo, writing, “Bas Princen’s photograph Ringroad (Houston) encapsulates, through its simple presence and curious ambiguity, almost everything I feel we can ever say about architecture,” continuing over the rest of his essay to explain how the photo went on to influence Geers’s own architectural design work.

My own look at the image is in the context of Princen’s output, from Los Angeles to Dubai, focusing on his images in which “there is often an extraordinary, building-size geometric shape in the center of the frame, yet it is not always clear if it can be described as architecture. (…) Rather, these abstract objects—sometimes mirrored, sometimes with no visible points of entry—function more like undeclared monuments with no clear subject of commemoration. They are, in a sense, both unexplained and inexplicable.”

[Image: “Cooling Plant, Dubai” (2009) by Bas Princen; while this photograph does not appear in The Construction of the Image, I mention it in my essay as an inversion of “Ringroad (Houston)”].

[Image: “Cooling Plant, Dubai” (2009) by Bas Princen; while this photograph does not appear in The Construction of the Image, I mention it in my essay as an inversion of “Ringroad (Houston)”].

If you’re curious to see a slightly different sort of approach, Princen’s photos are also—as of yesterday—on display at the Met Breuer museum in New York City.

In a show called Breuer Revisited, photographers Luisa Lambri and Princen both offer their own distinctive visual analyses of four buildings designed by Marcel Breuer.

“Evoking minimalism and abstraction,” the museum explains, “Lambri creates images that examine the dialogue between interior and exterior, and the interaction between surface and light. Princen investigates and reframes urban and rural spaces through documenting the concept of post-occupancy, or the evolution of a building and its enduring relevance.”

The show is open until May 21, 2017; The Construction of an Image is available through the Architectural Association.

(Earlier: Pieces of the city are forming, like islands).

Last week, over at the

Last week, over at the  Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

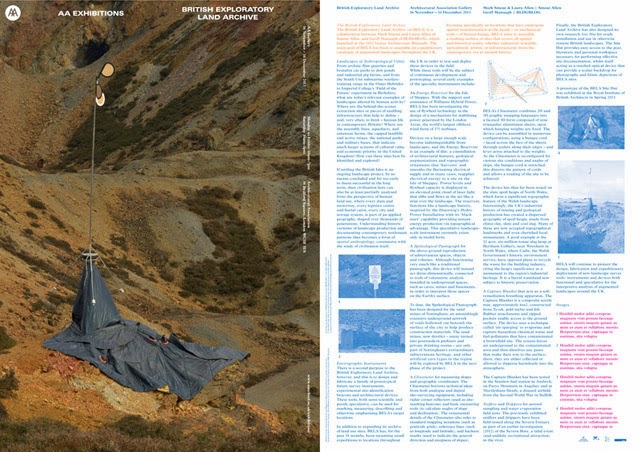

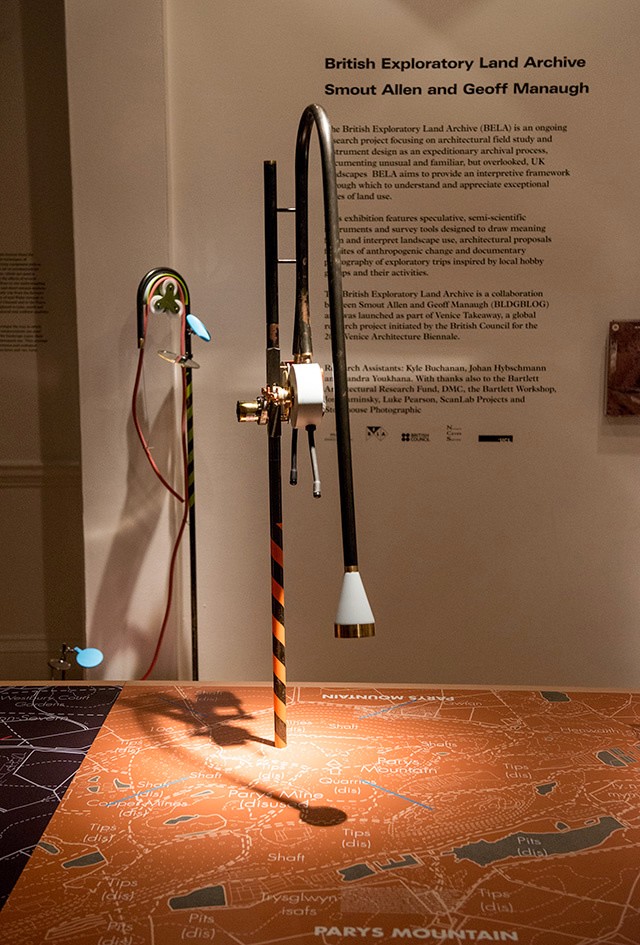

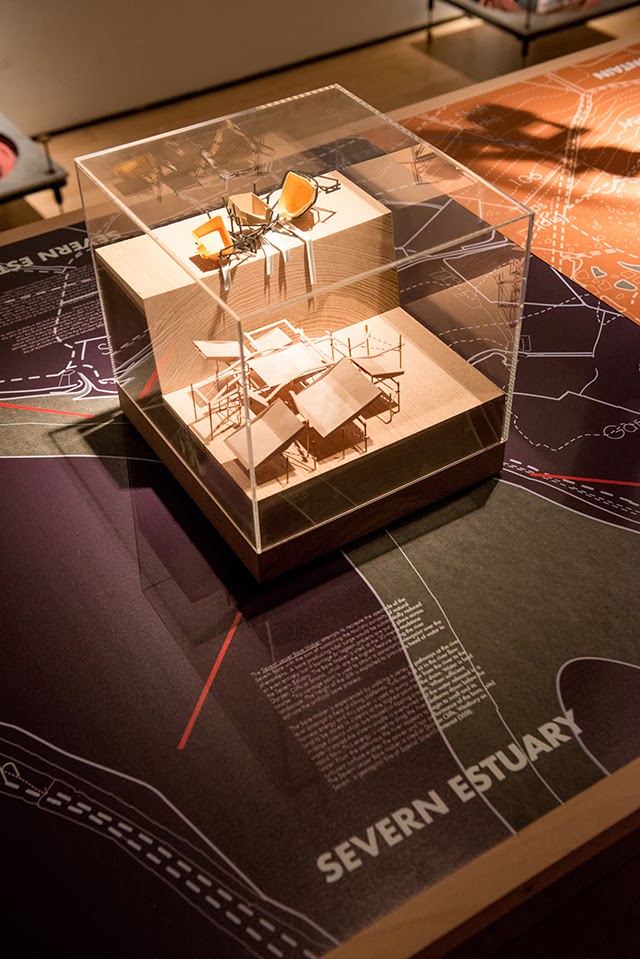

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the  From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since  In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with

In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with  This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

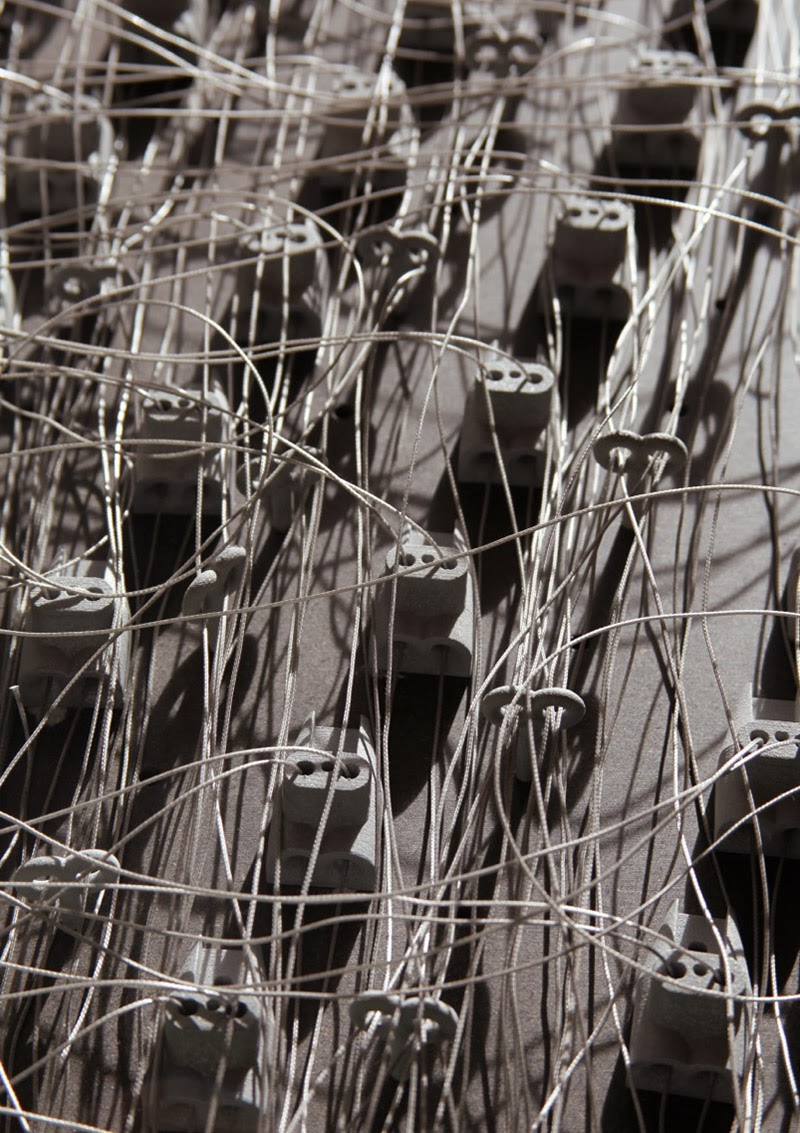

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.  The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the

The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the  Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

The exhibition is

The exhibition is