[Image: “Mix House” by Joel Sanders Architect, Karen Van Lengen/KVL, and Ben Rubin/Ear Studio].

[Image: “Mix House” by Joel Sanders Architect, Karen Van Lengen/KVL, and Ben Rubin/Ear Studio].

Between cross-country moves, book projects, wild changes in the online media landscape over the past few years, and needless self-competition through social media, my laptop has accumulated hundreds and hundreds, arguably thousands, of bookmarks for things I wanted to write about and never did. Going back through them all feels like staring into a gravesite at the end of a life I didn’t realize was mortal.

For example, the fact that the scent of one of Saturn’s moons was created in a NASA lab in Maryland—speculative offworld perfumery—and that, who knows, it could even someday be trademarked. Or that mountain-front suburban homes in Colorado were unwittingly constructed over mines designed to collapse—and that of the mines have already begun to do so, taking surface roads along with them. Or the sand mines of central Wisconsin. Or the rise of robot-plant hybrids. Or the British home built around a preserved railway carriage “because bizarre planning regulations meant the train could not be moved”—a vehicle frozen into place through architecture.

In any case, another link I wanted to write about many eons ago explained that legendary producer and ambient musician Brian Eno had been hired to design new acoustics for London’s Chelsea and Westminster hospital, part of an overall rethinking of their patient-wellness plan. Healing through sound. “The aim,” the Evening Standard explained, “is to replicate techniques in use in the hospital’s paediatric burns unit, where ‘distraction therapy’ such as projecting moving images on to walls can avoid the need to administer drugs such as morphine.”

This is already interesting—if perhaps also a bit alarming, in that staring at images projected onto blank walls can apparently have the same effect as taking morphine. Or perhaps that’s beautiful, a chemical testament to the mind-altering potential of art amplified by modern electrical technology.

Either way, Eno was brought on board to “refine” the hospital’s acoustics, much as one would do for the interior of a luxury vehicle, and even to “provide soothing music” for the building’s patients, i.e. to write a soundtrack for architecture.

We are already in an era where the interiors of luxury cars are designed with the help of high-end acoustic consultants, where luxury apartments are built using products such as “acoustic plaster,” and where critical governmental facilities are constructed with acoustic security in mind—a silence impenetrable to eavesdroppers—but I remain convinced that middle-budget home developers all over the world are sleeping on an opportunity for distinguishing themselves. That is, why not bring Brian Eno in to design soothing acoustics for an entire village or residential tower?

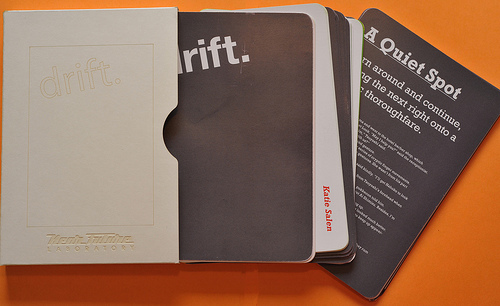

Imagine a whole new neighborhood in Los Angeles designed in partnership with Dolby Laboratories or Bang & Olufsen, down to the use of acoustic-deflection walls and carefully chosen, sound-absorbing plants, or an apartment complex near London’s Royal Academy of Music with interiors acoustically shaped by Charcoalblue. SilentHomes™ constructed near freeways in New York City—or, for that matter, in the middle of nowhere, for sonically sensitive clients. Demonstration suburbs for unusual acoustic phenomena—like Joel Sanders et al.’s “Mix House” scaled up to suit modern real-estate marketers.

At the very least, consider it a design challenge. It’s 2020. KB Home has teamed up with Dolby Labs to construct a new housing complex covering three city blocks near a freeway in Los Angeles. What does it look—and, more to the point, what does it sound—like?

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the