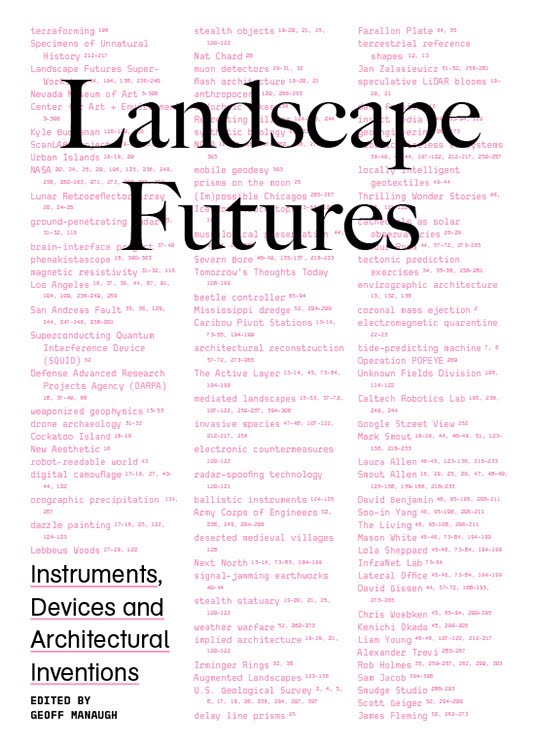

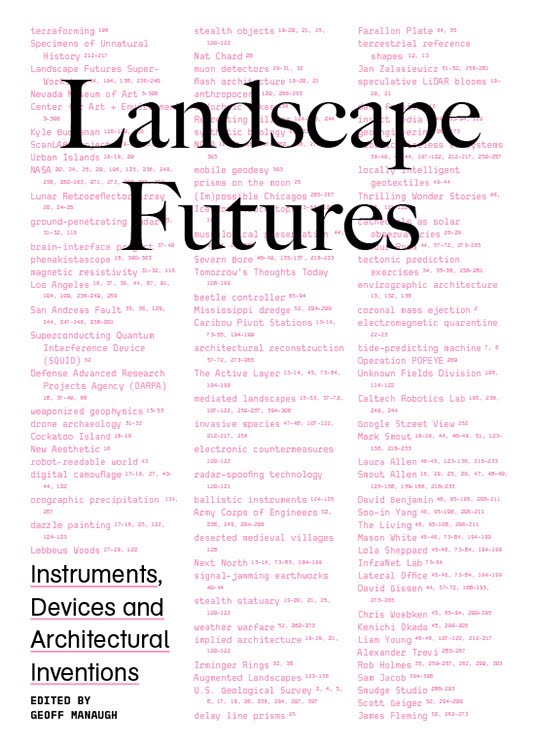

[Images: The cover of Landscape Futures; book design by Brooklyn’s Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: The cover of Landscape Futures; book design by Brooklyn’s Everything-Type-Company].

I’m enormously pleased to say that a book project long in the making will finally see the light of day later this month, a collaboration between ACTAR and the Nevada Museum of Art called Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions.

On a related note, I’m also happy to say simply, despite the painfully slow pace of posts here on the blog, going back at least the last six months or so, that many projects ticking away in the background are, at long last, coming to fruition, including Venue, and, now, the publication of Landscape Futures.

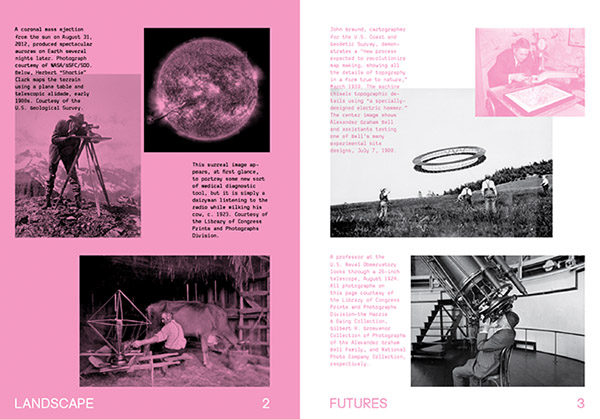

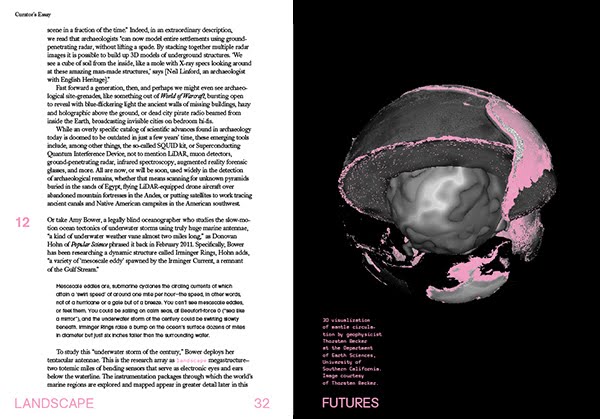

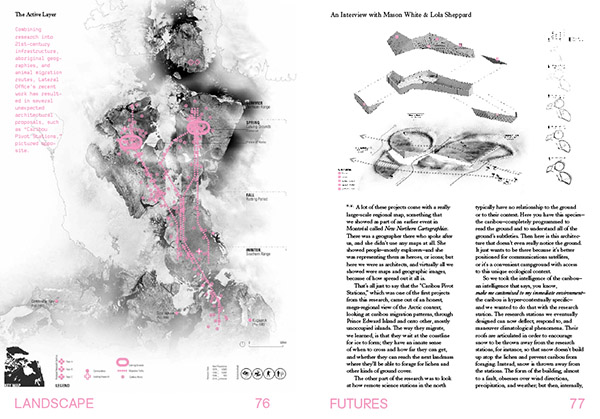

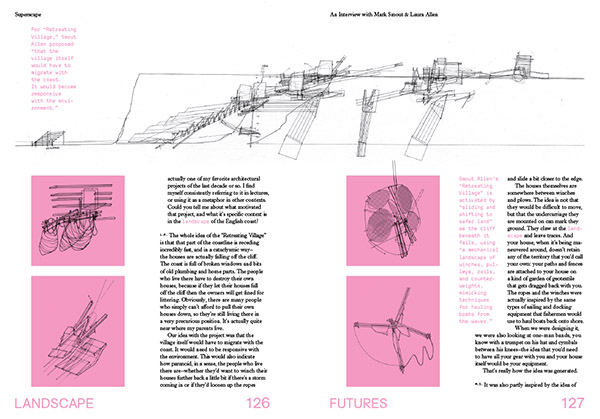

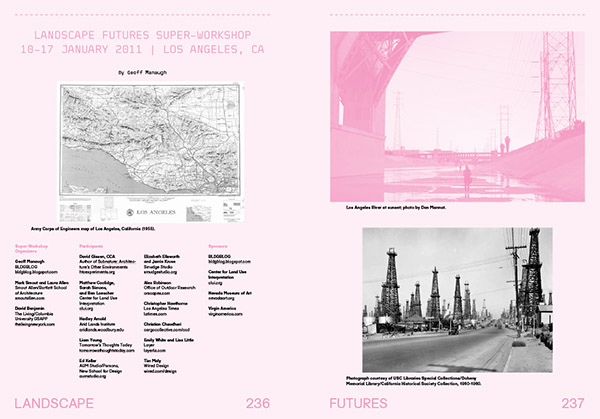

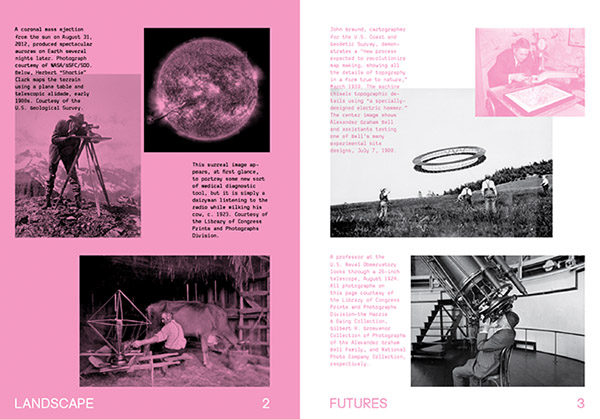

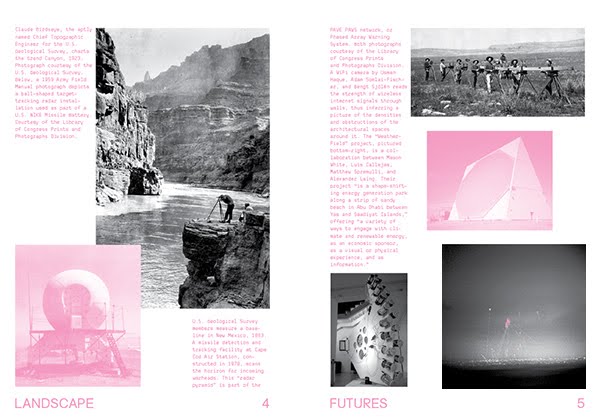

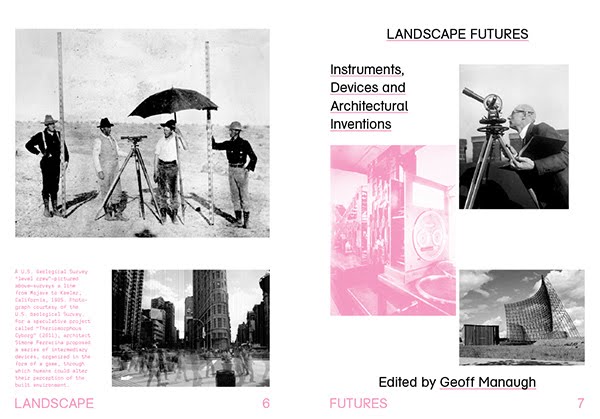

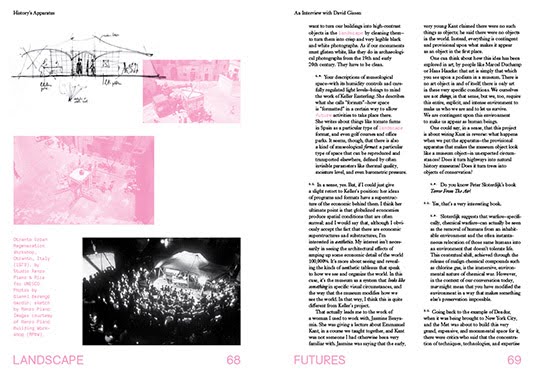

[Images: The opening spreads of Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: The opening spreads of Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

Landscape Futures both documents and continues an exhibition of the same name that ran for a bit more than six months at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, from August 2011 to February 2012. The exhibition was my first solo commission as a curator and by far the largest project I had worked on to that point. It was an incredible opportunity, and I remain hugely excited by the physical quality and conceptual breadth of the work produced by the show’s participating artists and architects.

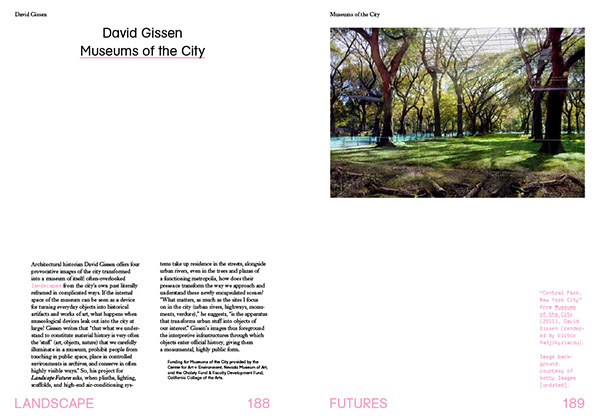

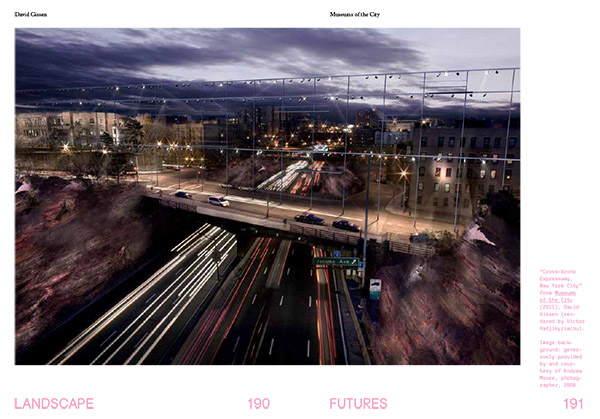

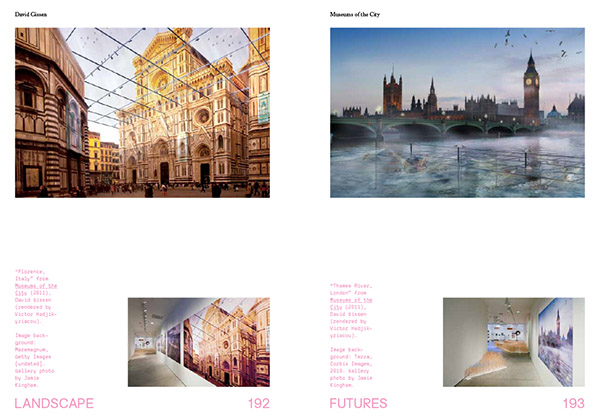

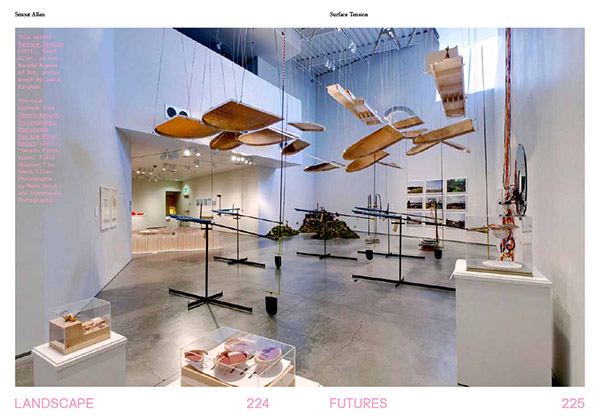

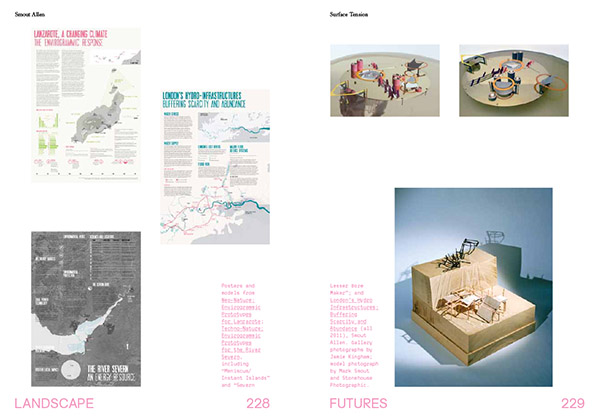

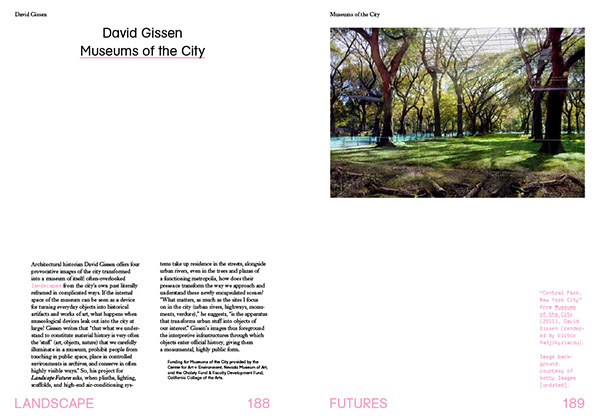

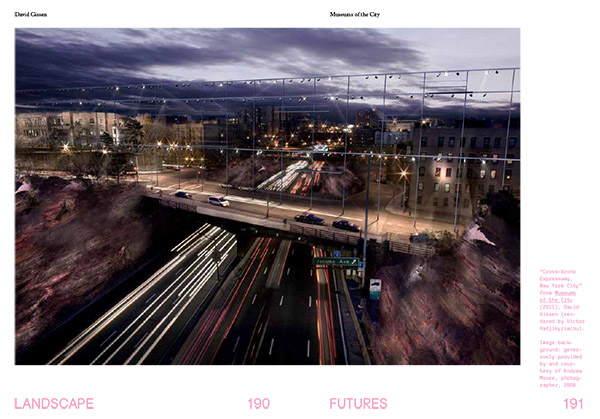

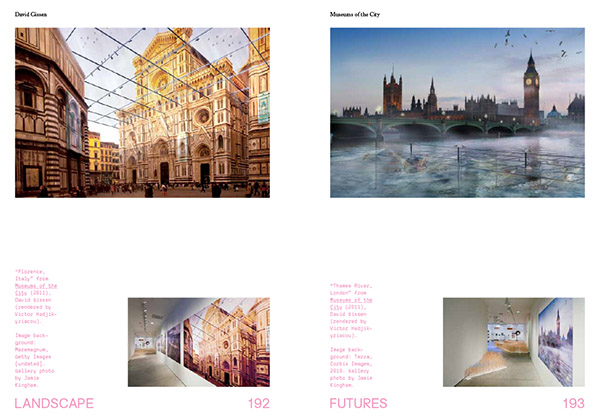

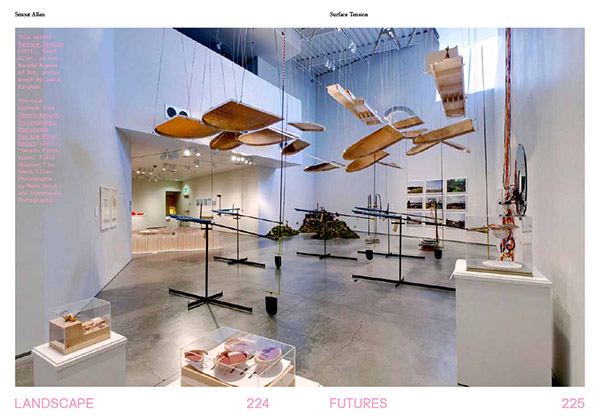

Best of all, I was able to commission brand new work from many of the contributors, including giving historian David Gissen a new opportunity to explore his ideas—on preservation, technology, and the environmental regulation of everyday urban space—in a series of wall-sized prints; finding a new genre—a fictional travelogue from a future lithium boom—with The Living; and setting aside nearly an entire room, the centerpiece of the 2,500-square-foot exhibition, for an immensely complicated piece of functioning machinery (plus documentary photographs, posters, study-models, an entire bound book of research, and much else besides) by London-based architects Smout Allen.

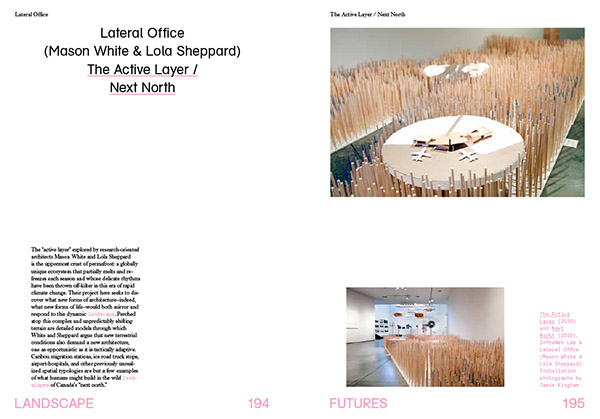

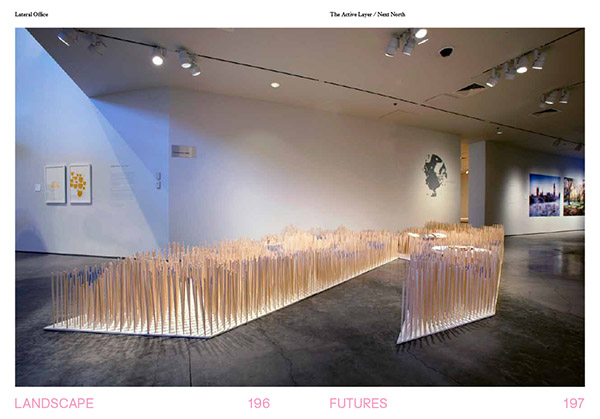

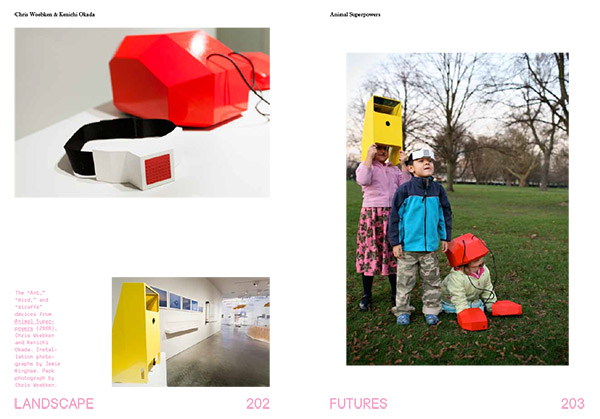

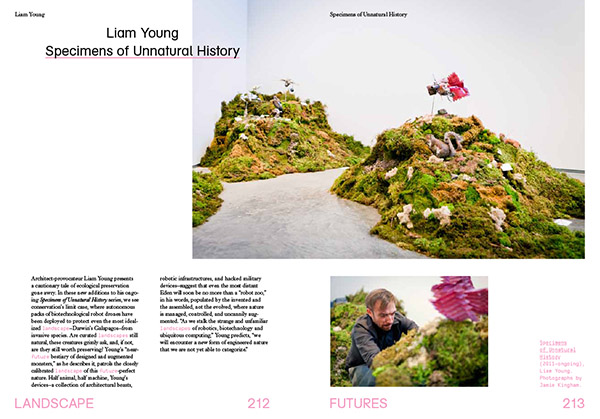

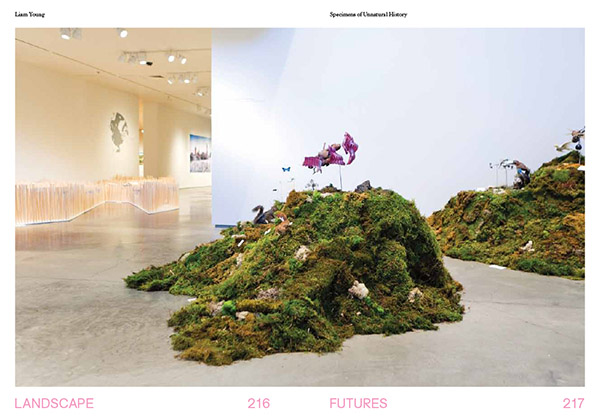

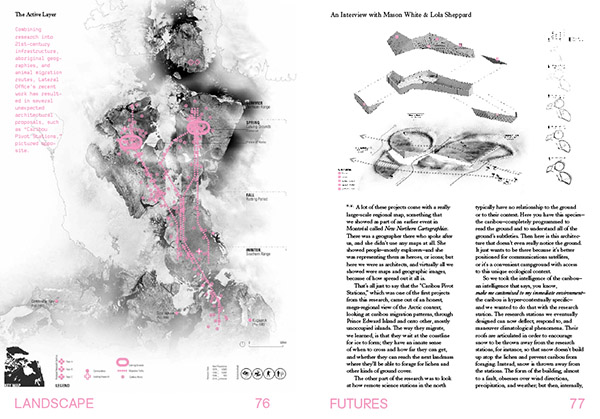

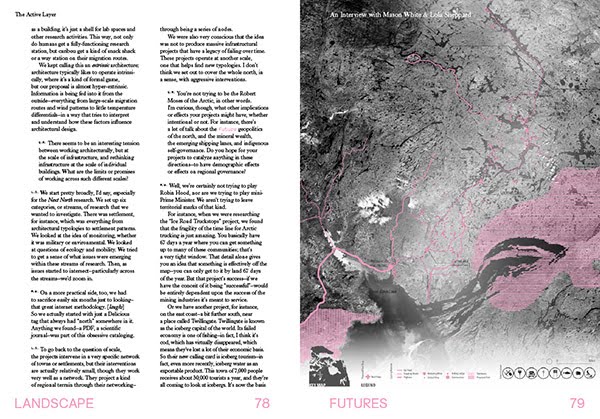

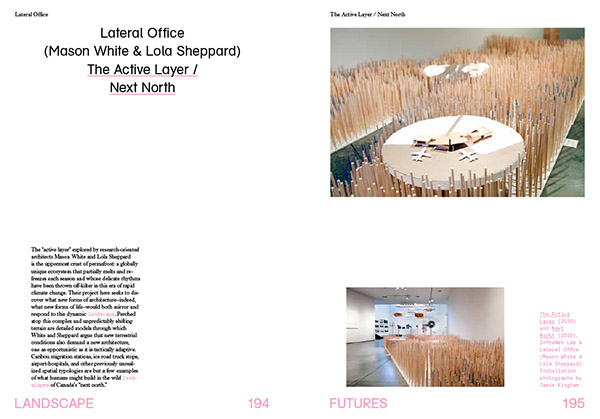

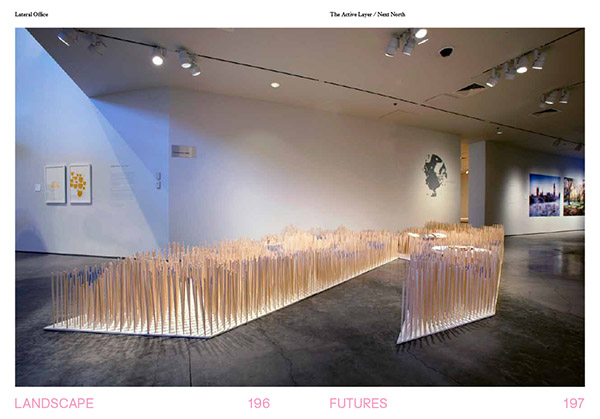

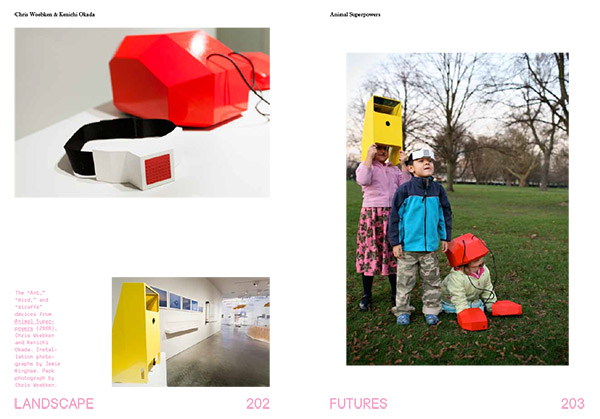

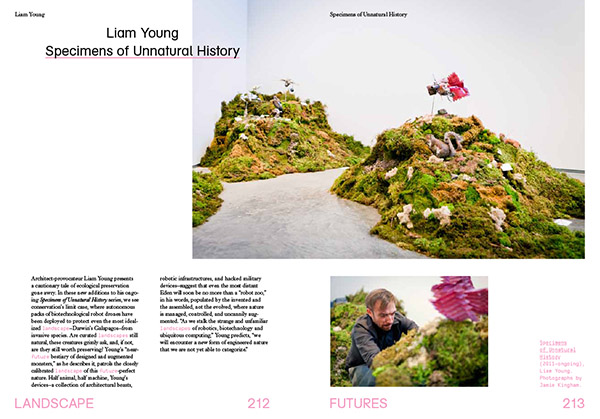

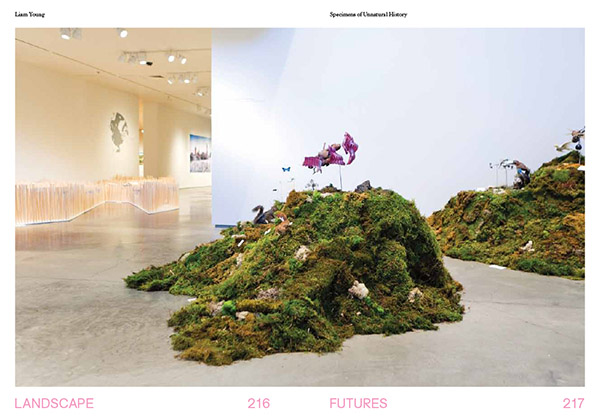

Those works joined pre-existing projects by Mason White & Lola Sheppard of Lateral Office and InfraNet Lab, whose project “Next North/The Active Layer” explored the emerging architectural conditions presented by climate-changed terrains in the far north; Chris Woebken & Kenichi Okada, whose widely exhibited “Animal Superpowers” added a colorful note to the exhibition’s second room; and architect-adventurer Liam Young, who brought his “Specimens of Unnatural History” successfully through international customs to model the warped future ecosystem of a genetically-enhanced Galapagos.

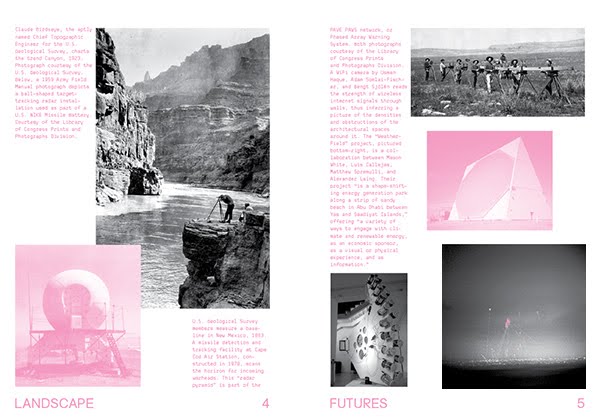

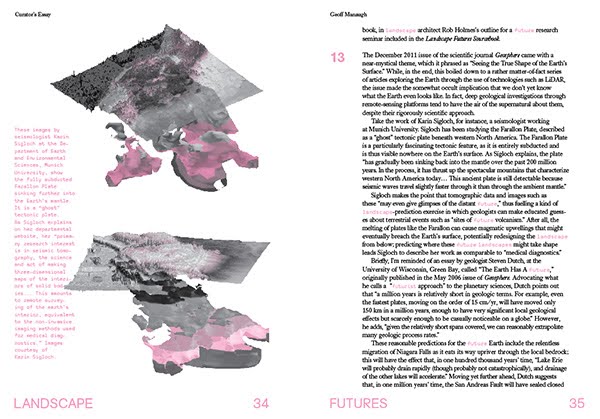

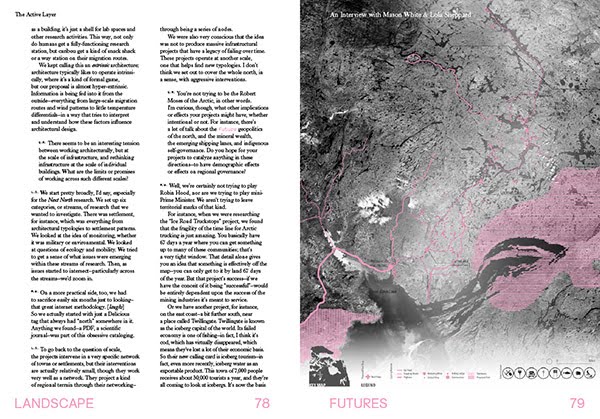

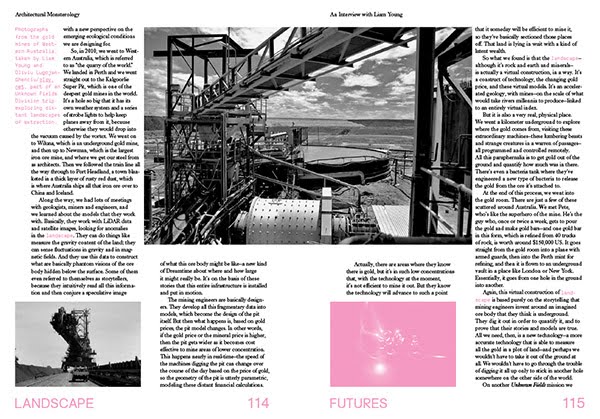

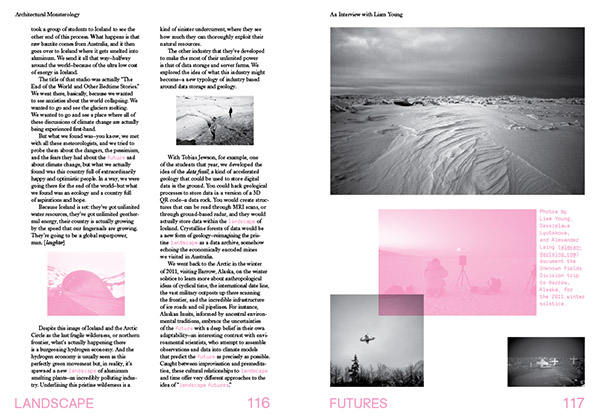

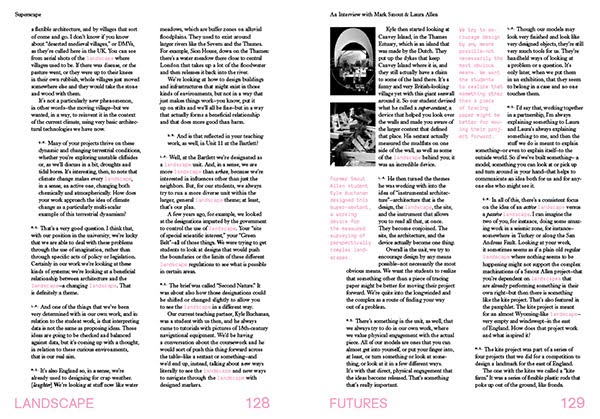

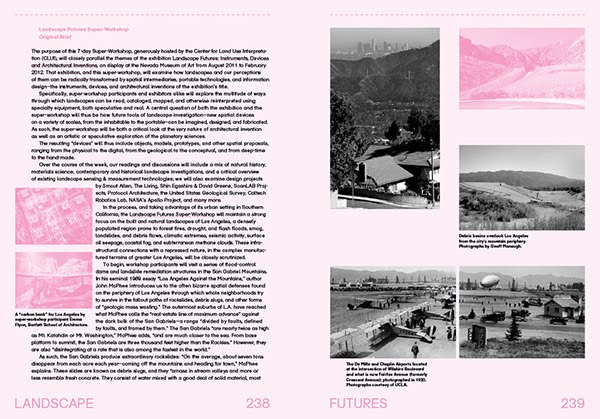

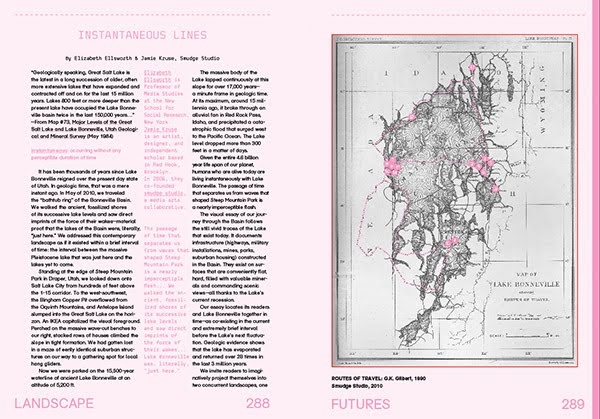

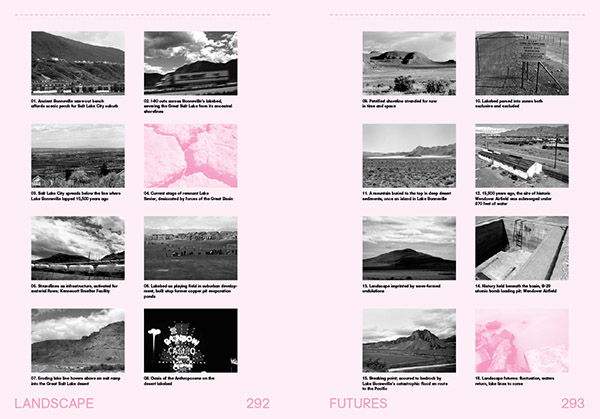

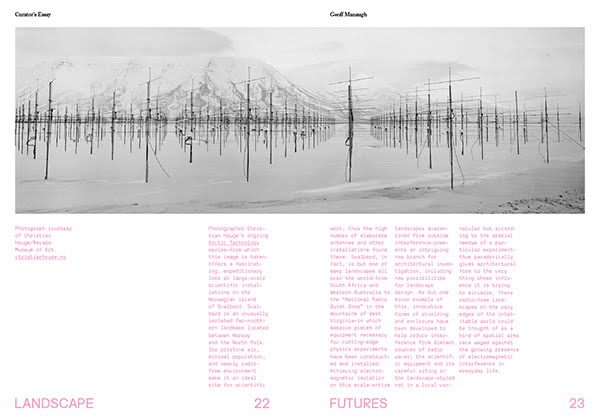

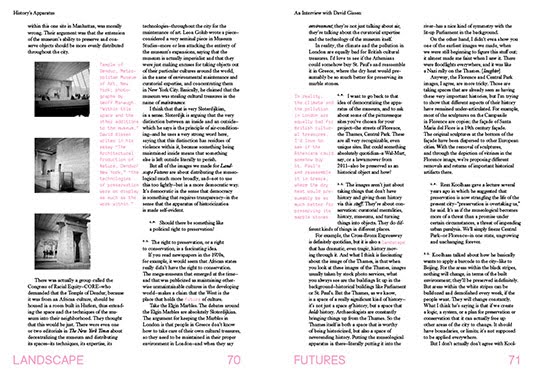

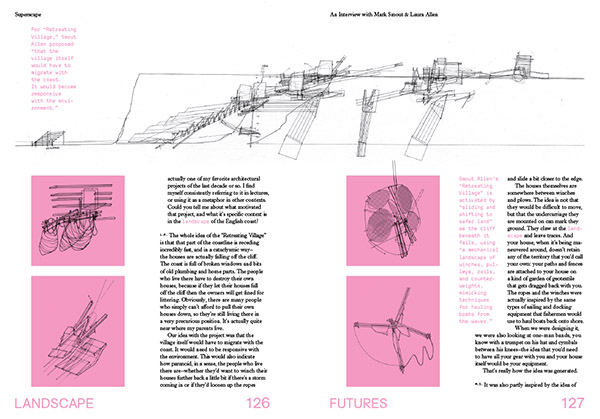

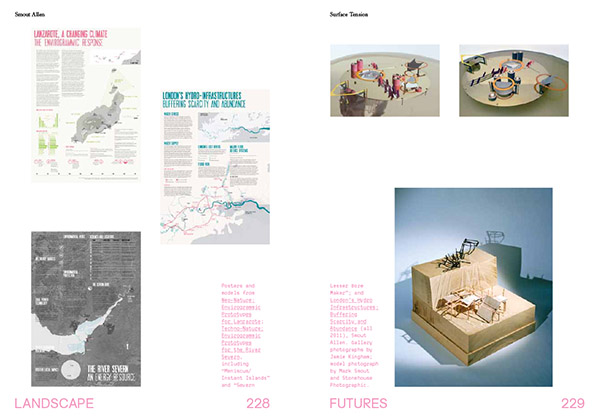

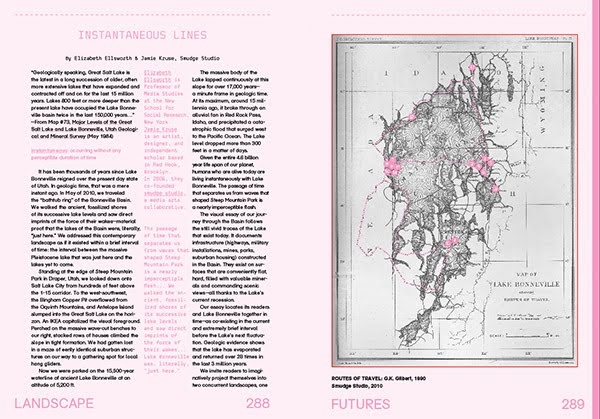

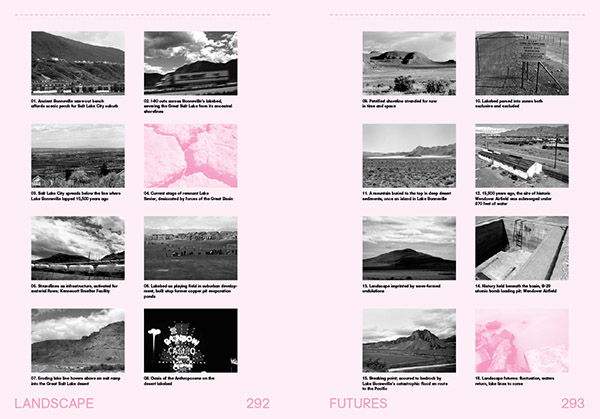

[Images: More spreads from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: More spreads from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

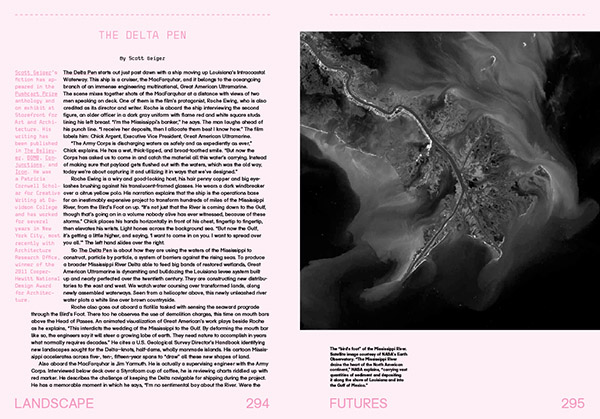

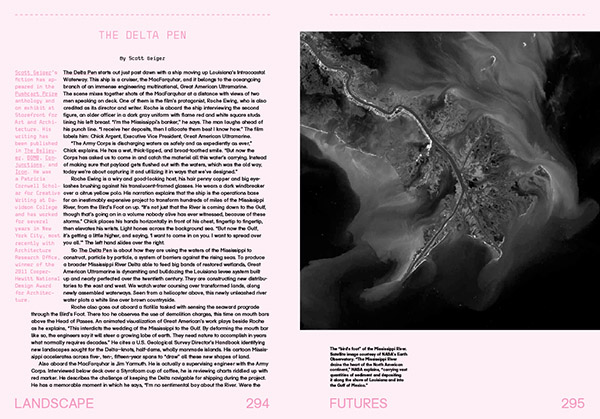

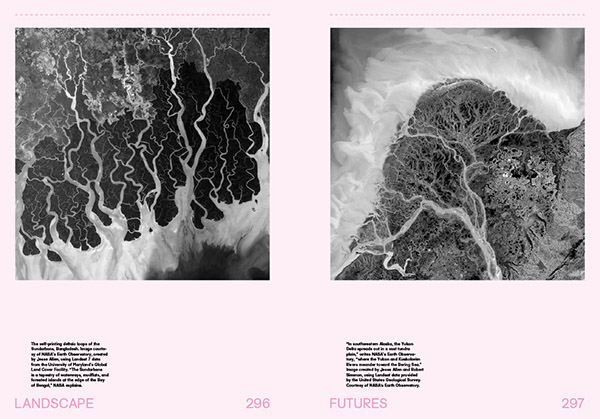

But the book also expands on that core of both new and pre-existing work to include work by Rob Holmes, Alex Trevi (edited from their original appearance on Pruned), a travelogue through the lost lakes of the American West by Smudge Studio, a walking tour through the electromagnetic landscapes of Los Angeles by the Center for Land Use Interpretation, and a new short story by Pushcart Prize-winning author Scott Geiger.

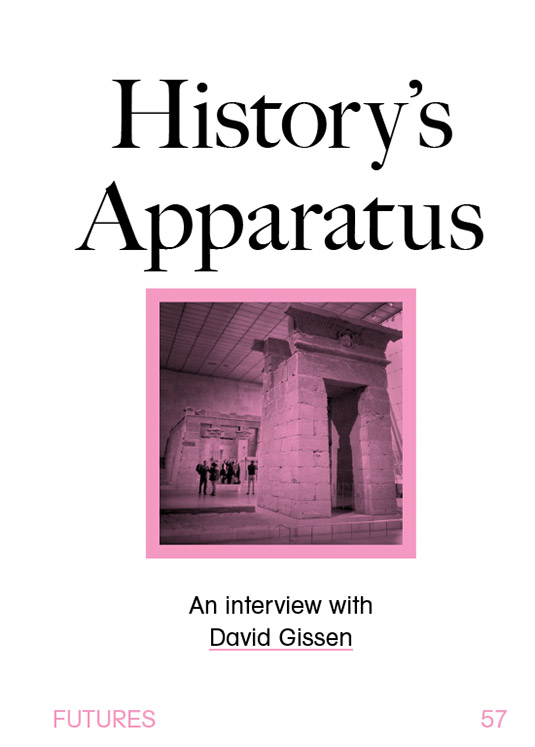

These, in turn, join reprints of texts highly influential for the overall Landscape Futures project, including a short history of climate control technologies and weather warfare by historian James Fleming, David Gissen‘s excellent overview of the atmospheric preservation of artifacts in museums in New York City (specifically, the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and a classic article—from BLDGBLOG’s perspective, at least—originally published in New Scientist back in 1998, where geologist Jan Zalasiewicz suggests a number of possibilities for the large-scale fossilization of entire urban landscapes in the Earth’s far future.

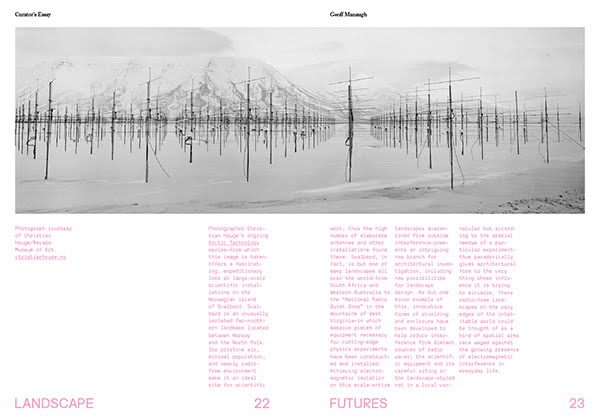

Even that’s not the end of the book, however, which is then further augmented by a long look, in the curator’s essay, at the various technical and metaphoric implications of the instruments, devices, and architectural inventions of the book’s subtitle, from robot-readable geotextiles and military surveillance technologies to the future of remote-sensing in archaeology, and moving between scales as divergent as plate-tectonic tomography, radio astronomical installations in the the polar north, and speculative laser-jamming objects designed by ScanLAB Projects.

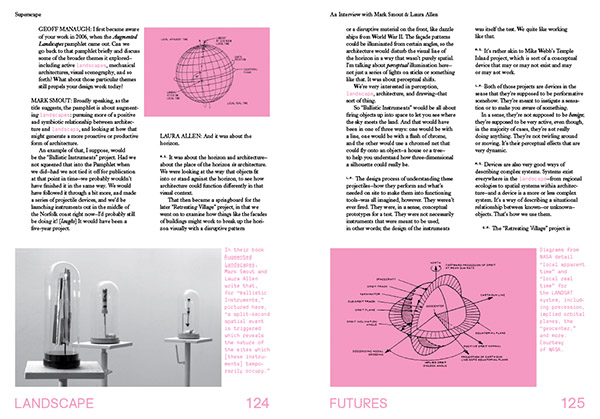

To wrap it all up and connect the conceptual dots set loose across the book, detailed interviews with all of the exhibition’s participating artists, writers, and architects fill out the book’s long middle—and, in all cases, I can’t wait to get these out there, as they are all conversations that deserve continuation in other formats. The responses from David Gissen alone could fuel an entire graduate seminar.

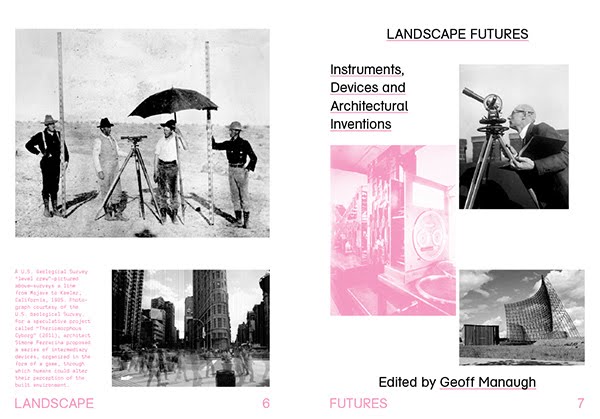

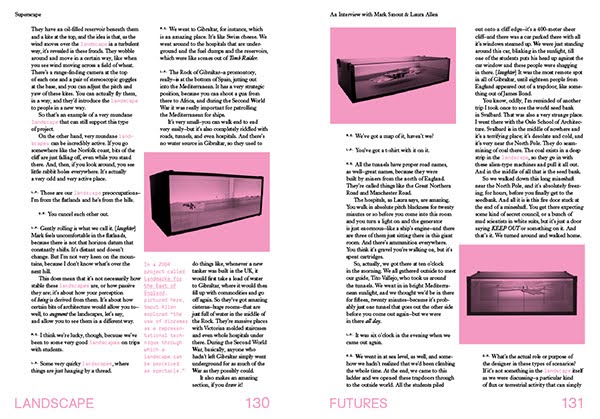

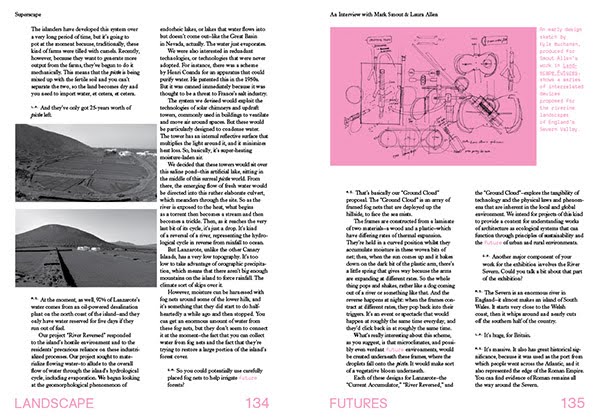

The spreads and images you see here all come directly from the book.

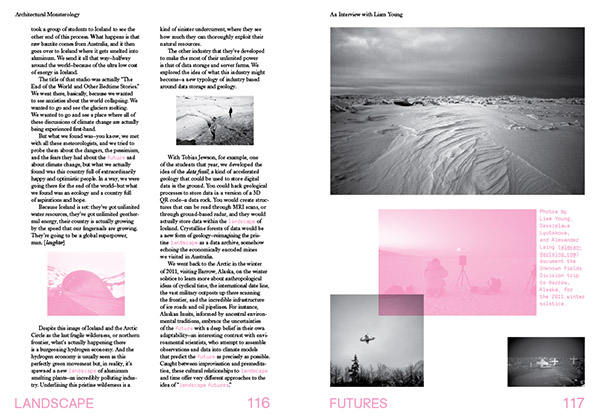

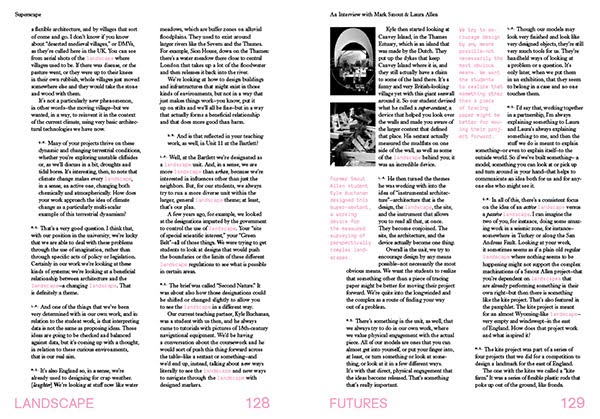

[Images: Spreads from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: Spreads from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

Of course, the work itself also takes up a large section in the final third or so of the book; consisting mostly of photographs by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, these document the exhibition contents in their full, spatial context, including the double-height, naturally lit room in which the ceiling-mounted machinery of Smout Allen whirred away for six months. This is also where full-color spreads enter the book, offering a nice pop after all the pink that came before.

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

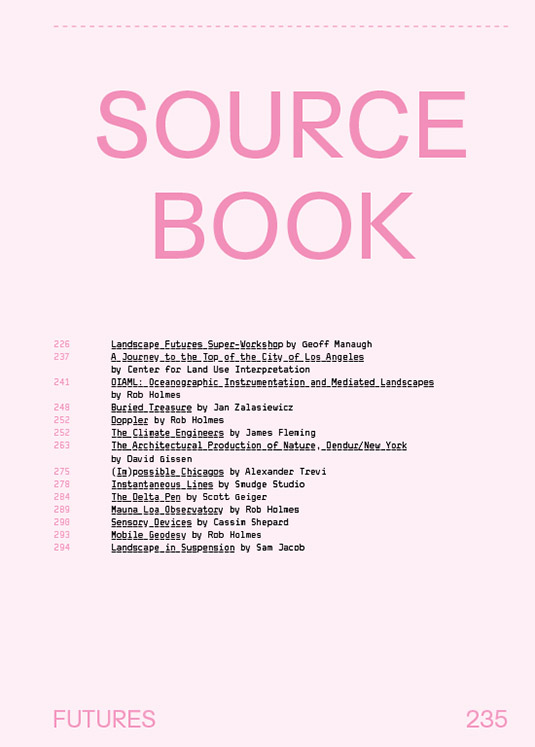

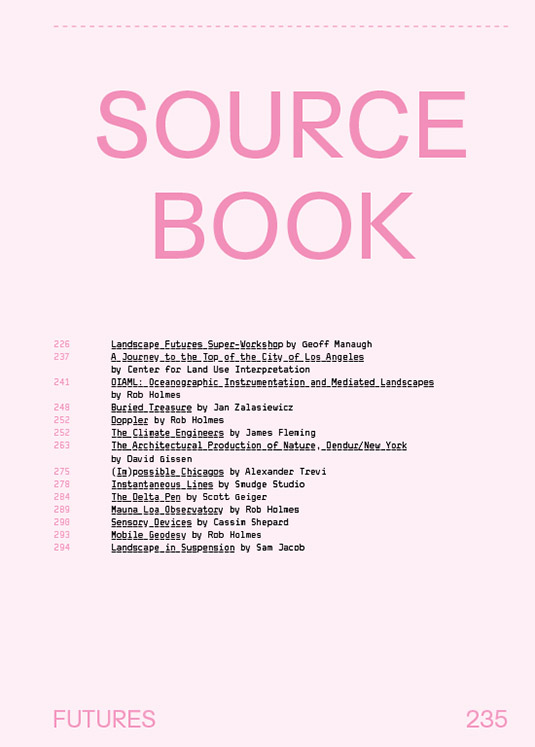

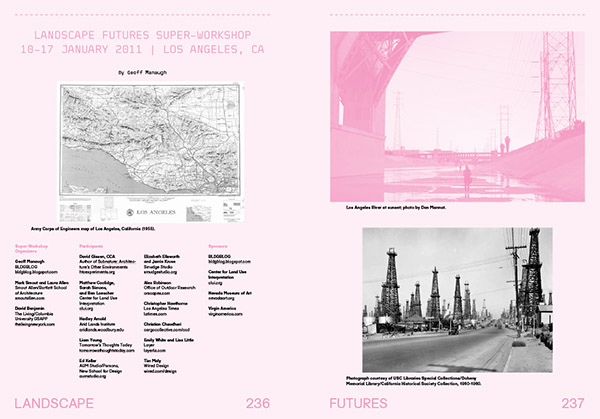

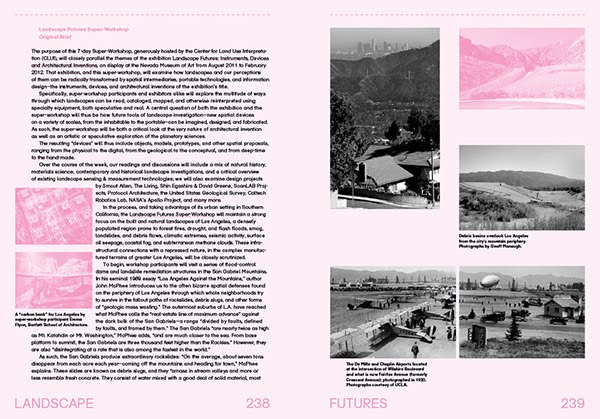

Which brings us, finally, to the Landscape Futures Sourcebook, the final thirty or forty pages of the book, filled with the guest essays, travelogues, walking tours, photographs, a speculative future course brief by Rob Holmes of Mammoth, and the aforementioned short story by Scott Geiger.

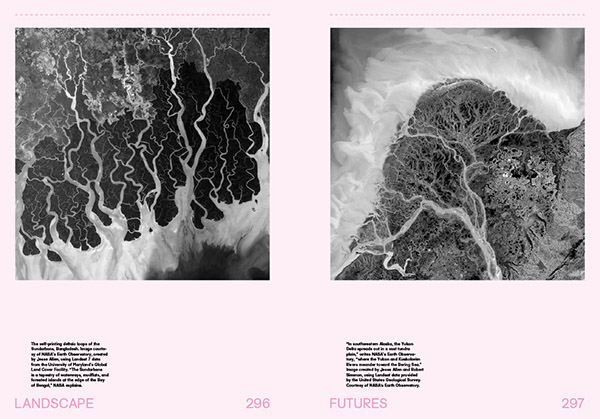

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

Needless to say, I am absolutely thrilled with the incredible design work done by Everything-Type-Company—a new and rapidly rising design firm based in Brooklyn, founded by Kyle Blue and Geoff Halber—and I am also over the moon to think that this material will finally be out there for discussion elsewhere. It’s been a long, long time in the making.

In any case, shipping should begin later this month. Hopefully the above glimpses, and the huge list of people whose graphic, textual, or conceptual work is represented in the book, will entice you to support their effort with an order.

Enjoy!

(Thank you to all the people and organizations who made Landscape Futures possible, including the Nevada Museum of Art and ACTAR, supported generously by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Study in the Fine Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts).

An interesting symposium at Columbia University later this month looks at “the ecology of New York City“:

An interesting symposium at Columbia University later this month looks at “the ecology of New York City“:

[Image: The WWI terrain model of Messines, Belgium, in Cannock Chase, England; photo, “taken probably 1918 by Thomas Frederick Scales,” courtesy of the

[Image: The WWI terrain model of Messines, Belgium, in Cannock Chase, England; photo, “taken probably 1918 by Thomas Frederick Scales,” courtesy of the  [Image: The concrete model at Cannock Chase, including a viewing hut; photo via

[Image: The concrete model at Cannock Chase, including a viewing hut; photo via  [Image: A viewing hut for studying the model landscape; photo via

[Image: A viewing hut for studying the model landscape; photo via  [Image: The scale of the model becomes more clear in this photo, also via

[Image: The scale of the model becomes more clear in this photo, also via

[Image: The Central Park bolt, photographed by

[Image: The Central Park bolt, photographed by  [Image: A photo of Benchmark B taken by Tullio Aebischer, courtesy of

[Image: A photo of Benchmark B taken by Tullio Aebischer, courtesy of

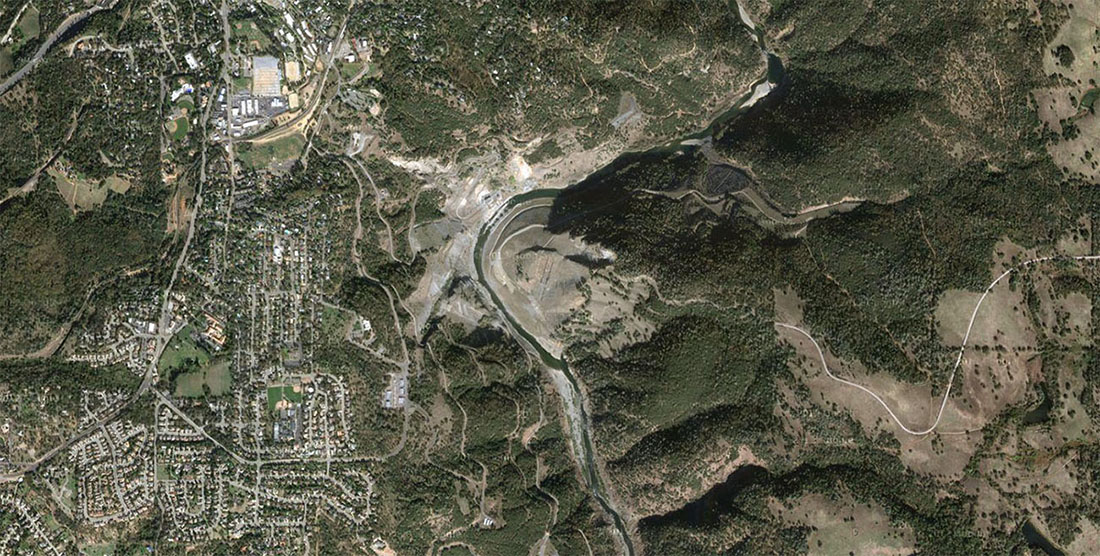

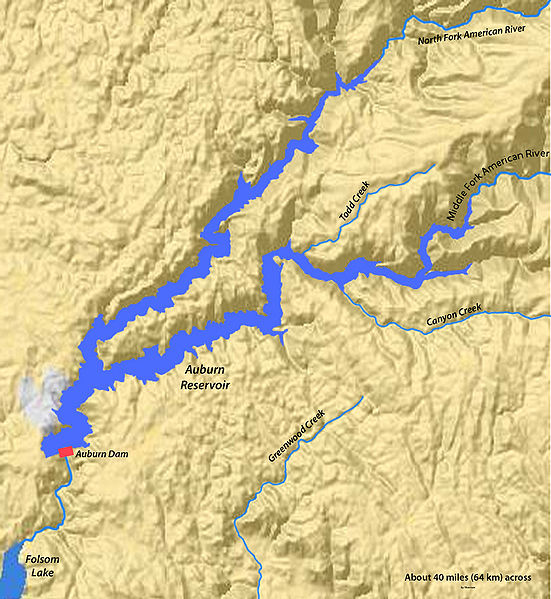

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via

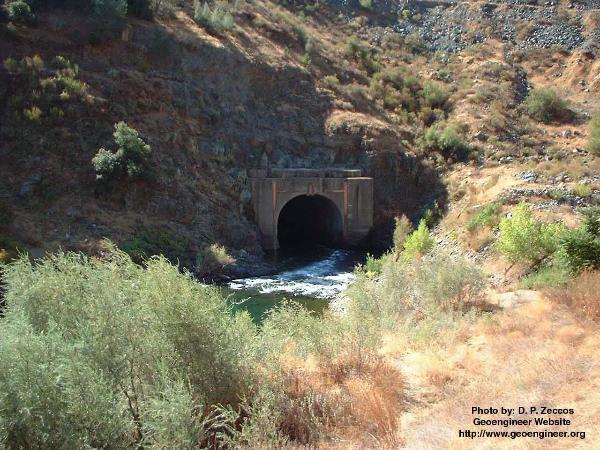

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via  [Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of

[Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of  [Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via

[Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via  [Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via

[Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via

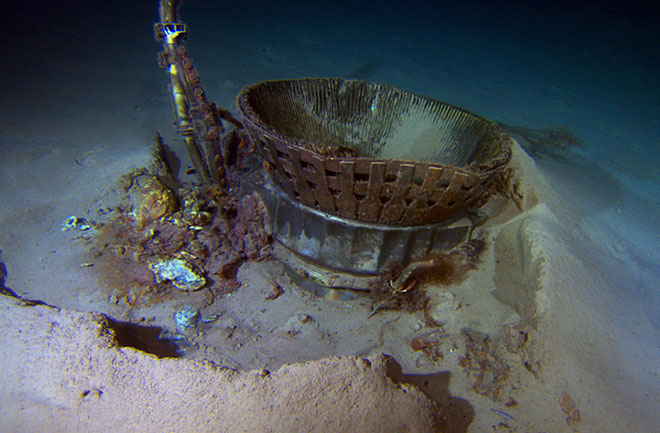

[Image: Fallen rockets at the bottom of the sea; photo by

[Image: Fallen rockets at the bottom of the sea; photo by

[Images: Photos from

[Images: Photos from  [Image: Photo from

[Image: Photo from  [Image: Photo from

[Image: Photo from

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: More spreads from

[Images: More spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “