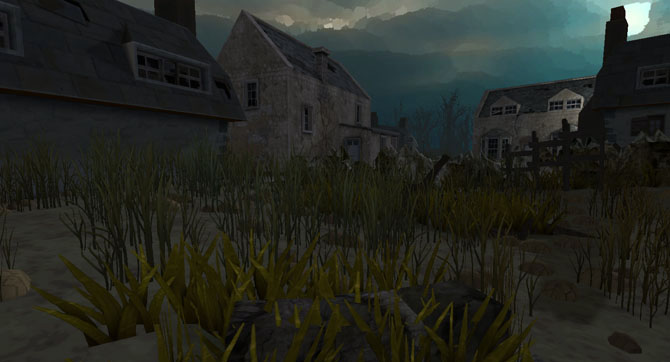

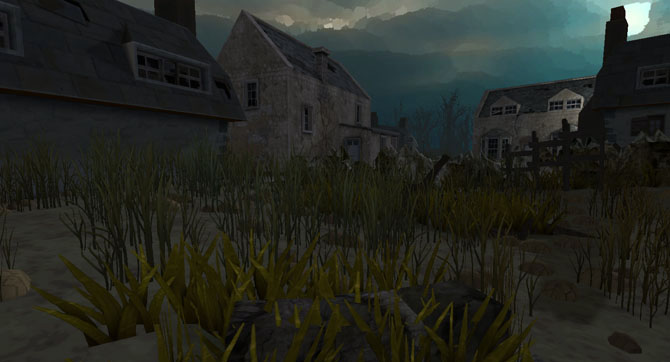

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

For the last ten months or so, I’ve been watching from afar the development of ground forms and landscapes for a game called Sir, You Are Being Hunted, from Big Robot.

Big Robot, of course, is a small game design firm founded by Jim Rossignol, who has guest-posted here on BLDGBLOG a few times over the years and who I interviewed back in 2009 about his book This Gaming Life.

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

What I’ve been captivated by is the so-called British Countryside Generator, a “procedural world engine” using “spatial division maths” that allowed Big Robot to generate aesthetically recognizable rural British landscapes.

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

“I’ve worked on a number of procedural world generation tools before,” coder Tom Betts explains on the Big Robot blog, “but this particular engine is unique in that the intention was to generate a vision of ‘British countryside,’ or an approximation thereof.”

To approach this we identified a number of features in the countryside that typify the aesthetic we wanted, and seem to be quintessential in British rural environments. Possibly the most important element is the ‘patchwork quilt’ arrangement of agricultural land, where polygonal fields are divided by drystone walls and hedgerows. These form recognizable patterns that gently rise and fall across the rolling open countryside, enclosing crops, meadows, livestock and woodlands. This patchwork of different environmental textures is something that is very stereotypically part of the British landscape. I looked for a mathematical equivalent we could use to simulate this effect and quite quickly decided upon using Voronoi diagrams.

The basic topology is thus established, one that, despite its mathematical abstraction, “looks remarkably like… the British countryside.”

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

“Once this is done,” Tom continues, “the engine then uses the height information to produce a terrain splatmap where different textures are assigned to areas according to altitude, slope and region type. This results in sandy beaches, rocky highlands and meadows in between.”

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

These subtle glimpses of game geology disguise Jim Rossignol’s own mock enthusiasm for all things virtually terrestrial. “Terrain!” he exclaimed over at Rock, Paper, Shotgun last summer in a Walt Whitmanic moment of expansiveness. “It’s the undulating table on which the pieces of our play are set. It’s the sandbox in which we dig, and the garden in which we grow. Terrain: for exploring, for absorbing, for smoothing, for deforming. It is the unsung underfoot heroic substrate of all that is gaming, and much else besides.”

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

Speaking of “smoothing,” these automatically generated lines and divisions are not always ideal, and can often use some smudging. “There are also a number of ‘noisy’ functions,” Tom adds, “that make the textures intersect more organically by adding goat type trails, blurring and dithering. There are also additional alterations made to this splatmap later as the engine deploys the actual models too—walls, buildings and so on.”

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

Personally—perhaps it’s schadenfreude—I love to see all of architecture reduced to “walls, buildings and so on,” just tossed across the landscape like salt; to think of all the time spent on student architecture projects that could simply have been achieved using a countryside generator…

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

Roads and towns at the push of a button.

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

But then, of course, you add the “sir” being hunted, and you throw in the jangly figures carrying rifles and smoking pipes in the foggy landscape, and mere terrain becomes gamespace, a place of strategy and places to hide.

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Image: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

Landscape then becomes something you explore while looking down the barrel of a gun, wandering through “walls, buildings and so on” as a new and renewable world tiles into being all around you.

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

In his long blog post at Big Robot, for instance, Tom writes that “one of the most exciting parts of procedural content generation is the fact that it can produce unexpected results, [and] players can stumble across regions that due to a particular combination of features appear really unusual. In testing I’ve found villages collapsing over cliff edges, trees submerged in lakes and roads from nowhere to nowhere. There is actually something nice about finding these anomalies because it really feels like a unique discovery, proving that you are wandering your own, individual version of the game world.”

Jim Rossignol has discussed the game in more detail in several interesting interviews—such as with WhatCulture and Rock, Paper, Shotgun—where you’ll find more background and info, and a convincing glimpse of the game designer as landscape theorist.

For now, here are some further shots of the British Countryside Generator at work.

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

[Images: From Sir, You Are Being Hunted by Big Robot].

Briefly, I can’t let this post end without mentioning another, admittedly entirely unrelated project, something that itself could easily be described as a “British countryside generator.” I’m referring to the massive wetland redevelopment on Wallasea Island, using “approximately 6.5m tons of spoil,” in the words of London Reconnections, that have been sucked, scraped, and excavated from deep beneath London as part of the Herculean Crossrail tunneling project.

In other words, the island is literally being expanded through an open-air terrestrial 3D-printing exercise, using dirt from the foundations of London as its ink.

[Image: Wallasea Island Map from Google Maps, via London Reconnections].

[Image: Wallasea Island Map from Google Maps, via London Reconnections].

As the BBC explains, the Wallasea wetland project is “making good use of the excess earth being generated from the separate £14.8bn Crossrail project. The twin-bore tunnels being dug out to link east and west London would have seen six million tons of earth in need of a new home—but three-quarters of this will head to Wallasea Island via freight trains and ships to create the new reserve.”

There is something absolutely mind-boggling in the idea of huge, artificial hollows under London being sprayed out over a coastal site—no doubt according to Big Robot-like formal rules, where “different textures are assigned to areas according to altitude, slope and region type,” as the game designer explains, above—to form, nearly from whole cloth, a new ecosystem.

A British Countryside Generator, indeed.

(An earlier version of this post mistakenly attributed many quotations to Jim Rossignol, rather than to Tom Betts—my apologies to Tom for the oversight!)

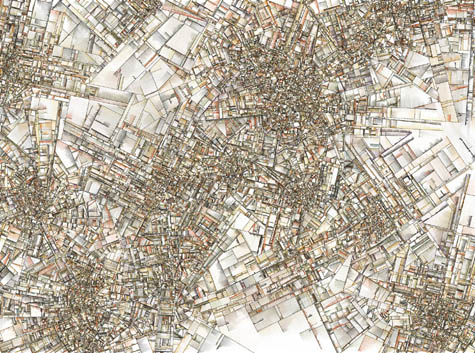

[Images: From @strangethink23].

[Images: From @strangethink23]. [Images: From @strangethink23].

[Images: From @strangethink23].

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Wallasea Island Map from Google Maps, via

[Image: Wallasea Island Map from Google Maps, via  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From Jared Tarbell’s

[Image: From Jared Tarbell’s

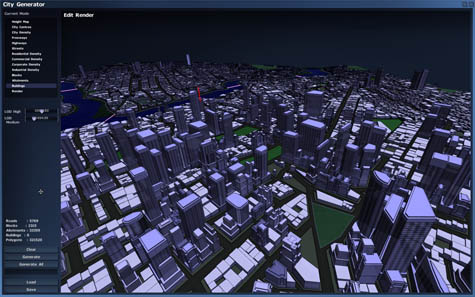

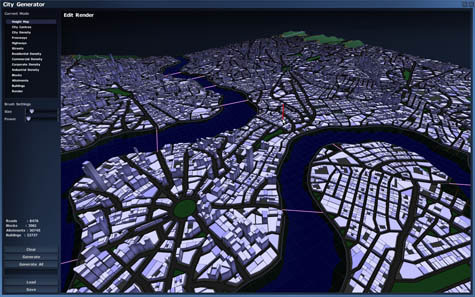

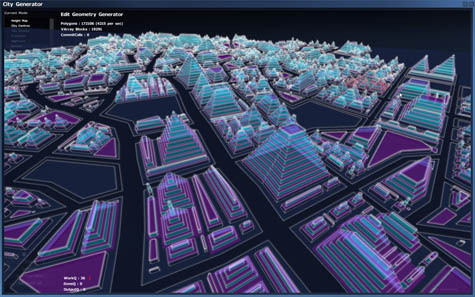

[Images: From Chris Delay’s

[Images: From Chris Delay’s  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From Chris Delay’s

[Image: From Chris Delay’s  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: From Marco Corbetta’s Structure].

[Image: From Marco Corbetta’s Structure].