[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

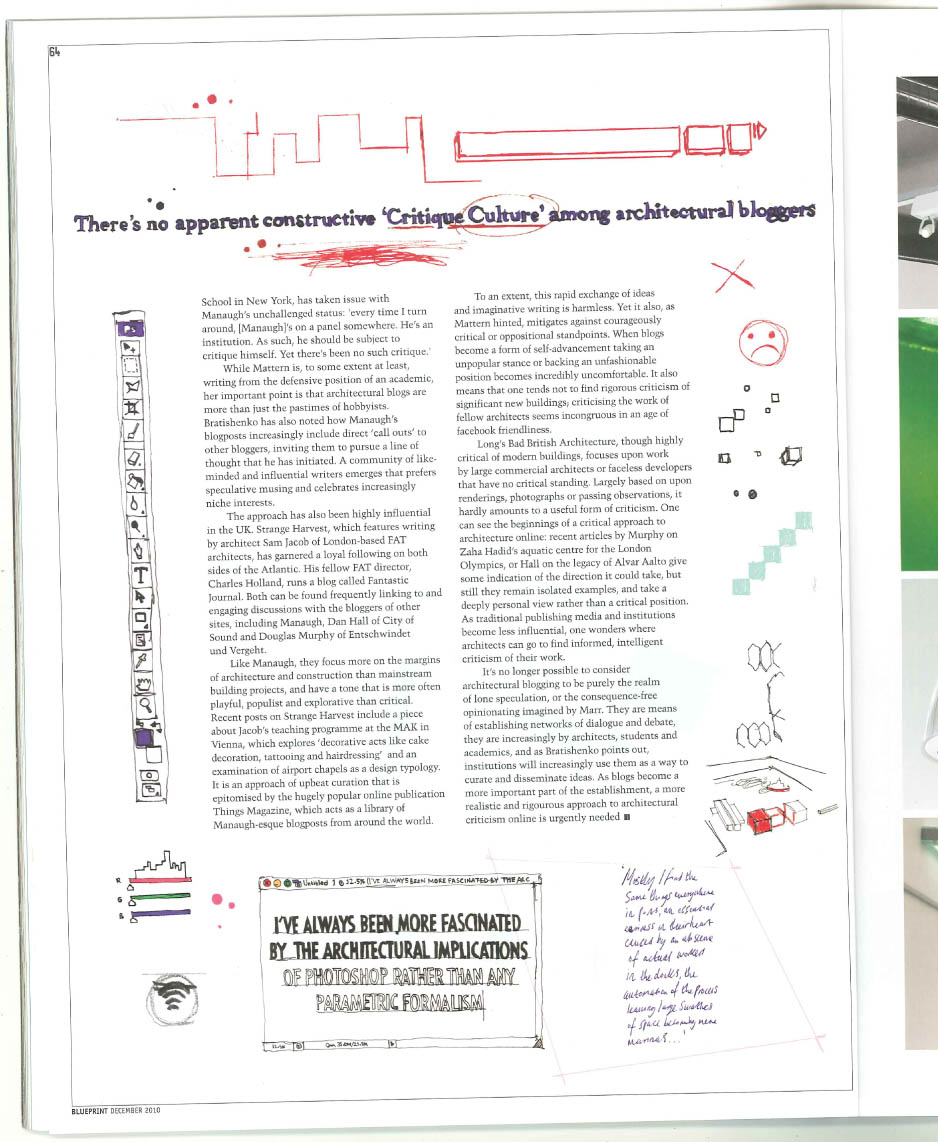

There’s an interesting and provocative article in the most recent issue of Blueprint called “The New Establishment,” by Peter Kelly. In it, Kelly takes issue with the lack of formal criticism in architecture blogging today, writing that “one tends not to find rigorous criticism of significant new buildings” on sites such as Strange Harvest, things magazine, and BLDGBLOG.

Instead, he suggests, a “like-minded” community of writers has arisen, one “that prefers speculative musing and celebrates increasingly niche interests.” He adds, with not a small shade of foreboding, that, “as blogs become a more important part of the establishment, a more realistic and rigorous approach to architectural criticism online is urgently needed.” After all, “As traditional publishing media and institutions become less influential, one wonders where architects can go to find informed, intelligent criticism of their work.”

These are absolutely valid points. I agree wholeheartedly that a more vigorous critique of the built environment is needed, as it will always be; I’ve said this before, in fact, and I have not changed my mind since then. Infrastructure, the growth of police power in urban space, pedestrianization and mass transit schemes, improved access to cultural institutions, the politics of military landscapes, healthy housing projects, aging and the city—all of these topics need more coverage and broader public discussion. Kelly is right to suggest as much.

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

But what I find deeply confusing about Kelly’s article is that, rather than read websites or blogs which do, in fact, offer “criticism of significant new buildings,” as he puts it, Kelly specifically and only focuses on websites that claim to do nothing of the sort (with perhaps one exception: Kieran Long’s Bad British Architecture).

As such, Kelly’s article feels a bit like listening to someone who’s just spent two weeks looking around the classical music section only to come out complaining that he couldn’t find any death metal. Well, no shit: you were in the wrong section, and it’s your mistake not ours.

In fact, it is illogical to assume that, because this site in particular is more likely to post about topics like weaponized climate modification, Greek mythology, strange infestations, narrative film, haunted house novels, paleontology, and so on, rather than about a new suite of renderings released by Rem Koolhaas, or a new museum in outer Rome, that I am therefore uninterested in seeing buildings and their architects held accountable to rigorous standards of design. As it happens, I am very interested in that; I just don’t tend to write those pieces myself.

To draw an analogy, Kelly seems to be assuming that, because someone plays guitar, they must be willfully obstructing the careers of people who instead play saxophone. Kelly, in this context, plays saxophone; he wants a bigger audience for people who play saxophone; so he writes an article not critiquing other people who play saxophone but deliberately selecting a group of guitar players so that he can make the obvious point that they don’t play sax—and this is what passes for serious architectural criticism? No wonder its audience has evaporated.

What amazes me about these sorts of critiques of blogging—and they are becoming more and more common and predictable today, now that interest in academic architectural discourse has faded (if there was ever interest in it) in favor of other, more energetic, unapologetically interdisciplinary writing styles—is that these critics are actually complaining about the lack of something they themselves purport to do.

Put another way, writers like Kelly are complaining about the unacknowledged side-effects of their own inadequacy as architecture critics. If they had actually known what they were doing in the first place, then people would never have lost interest in “rigorous criticism of significant new buildings.”

That is, speaking directly to Peter Kelly, if you want to see a more vigorous critique of real buildings, then, by all means, go ahead and show us how it’s done. Make it popular again. Find an audience for that type of writing and cultivate it. Convincingly demonstrate the power of the genre you so openly wish to celebrate.

But for Kelly to complain that BLDGBLOG doesn’t tour Alice Tully Hall, for instance, and offer constructive feedback for the architects is like complaining that Point Break doesn’t have anything to say about the design of the High Line, or that The Hobbit lacks exegetical interludes about the theories of Walter Benjamin—but neither of those things are about that, and they’re not without value because of it. They are, we might say, valued otherwise: performing an altogether different cultural function than the one whose absence Kelly mourns.

In fact, it’s a serious methodological flaw for critics like Kelly to read only the blogs that aren’t about building criticism—he cites BLDGBLOG, Pruned, Tim Maly’s Quiet Babylon, and so on—in order to make the point that today’s blogosphere is lacking in building criticism. Talk about shooting your own skeet. It’s not only lazy, it’s tautological and it betrays a total lack of commitment to original research.

To use another musical analogy, it’s like listening to smooth jazz for six years and then complaining that not one of those songs had vocals by Dave Mustaine—well, you were listening to the wrong kind of music.

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

Pointing out that BLDGBLOG doesn’t offer traditionally recognizable formal criticism of the built environment misses the fact that the modus operandi of this blog is all but precisely not to do that. Indeed, this blog is and always has been very consciously about architecture and landscape in a representationally broad sense: exploring how spatial environments appear in film, literature, mythology, games, dreams, and comics, and to write about the otherwise radically under-reported side-effects of buildings and cities, from freak local weather systems and invasive species to psychiatric disorders and rodents. In fact, I would say that BLDGBLOG has never claimed to be a place “where architects can go to find informed, intelligent criticism of their work.” I don’t want to do that; that is not my goal as an architecture writer. But that doesn’t mean—nor does it in any way imply—that I don’t want to see other writers successfully demonstrate how that sort of criticism is done.

Again, to address writers and critics such as Kelly: you all have had so long to prove your point about the value of serious architectural research. You claim absolute, if not unique, critical priority for a style of architecture writing that you yourselves fail to produce in any convincing manner, and you’ve failed to find any real audience for the very thing you are hoping to promote. Even now, you have blogs, zines, pamphlets, international magazines, Ph.D. funding, radio shows, whole university departments, conferences, and teaching opportunities at your disposal. You can make documentaries for the BBC. Your words and ideas should speak for themselves.

With that in mind, how exactly is your failure to find an audience—indeed, even to find more writers like yourselves willing to write this stuff, surely a damning absence if there ever was one—the fault of a loose group of bloggers who prefer “speculative musing” and “increasingly niche interests”? What exactly are you saying here—that we are Katy Perry to your Shostakovich? Is that a universally negative thing?

To use a wildly overblown historical metaphor, it’s a bit like seeing a lost group of battle-shocked British troops suffering from amnesia as they wander down the streets of Philadelphia in the summer of 1778, asking, in all seriousness, why there isn’t more British influence on display. But one of the reasons we came here in the first place was to get away from people like you.

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of Blueprint].

In any case, having said all that, I want to reiterate that I actually agree with the underlying premise of Peter Kelly’s article: that we need more direct and engaged criticism of the built environment. This is true, and Kelly is right. We need more Christopher Hawthornes and fewer Nicolai Ouroussoffs. We need more Matthew Coolidges and fewer Philip Jodidios. We need the next J.G. Ballard.

But until architecture critics can find a way to make formal building criticism interesting, entertaining, emotional, funny, adventurous, sexy, or thrilling, it—and its popular appeal—will languish. If people like Kelly can’t bring it upon themselves to reinvigorate their chosen discipline, then it’s not the fault of Sam Jacob or Alex Trevi if they fail. We’re back to the saxophone/guitar thing: what you need to do, Peter Kelly, is learn to play your saxophone so well that everyone else stops liking guitar; you can’t just complain about successful guitar players. Or, in market-speak: put us guitar players out of business by offering the world better music. If you can do something amazing, then I want to hear it, too.

Consider this an open appeal, then, to all architecture critics unnecessarily scared of blogs: produce the texts you want us to read & study. Find writers working in the genre you’re actually talking about and constructively team up with them to promote good and rigorous criticism. Use multiple media. Cast your net wide. Don’t assume that to entertain is to lose critical insight. Remember that sometimes the most “significant new buildings” in public life today are not museums and concert halls, but film sets and game environments.

Indeed, Alex McDowell is a more influential architect than David Chipperfield, which means covering McDowell’s work is not just fringe speculation. Grand Theft Auto generates more conversations about crime and the city than the writings of Adolf Loos, which means discussing GTA is not just self-indulgent musing.

After all, there is absolutely no reason in the world why we can’t have blogs that “celebrate increasingly niche interests” alongside blogs that offer “rigorous criticism of significant new buildings”—in fact, there is no reason in the world why a single blog couldn’t simultaneously perform both functions. It would be a dream to read.

Imagine a world, then, where critics like Peter Kelly actually step up and demonstrate how to do the things they so enjoy pointing out as lacking in others. If they could succeed at this—and find an audience, and push an agenda, and gather influence, and raise the stakes of what it means to be an architecture blogger—then we would all, as writers and readers and builders, be stronger because of it.

And, if they don’t succeed—if they can’t pull it off—then they should do better than to pin the blame on others.

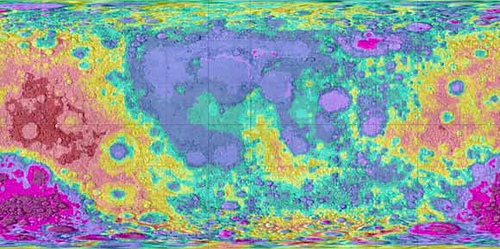

[Image: Lunar topography, courtesy of the USGS].

[Image: Lunar topography, courtesy of the USGS].

[Image: From the video, which appears below, showing the

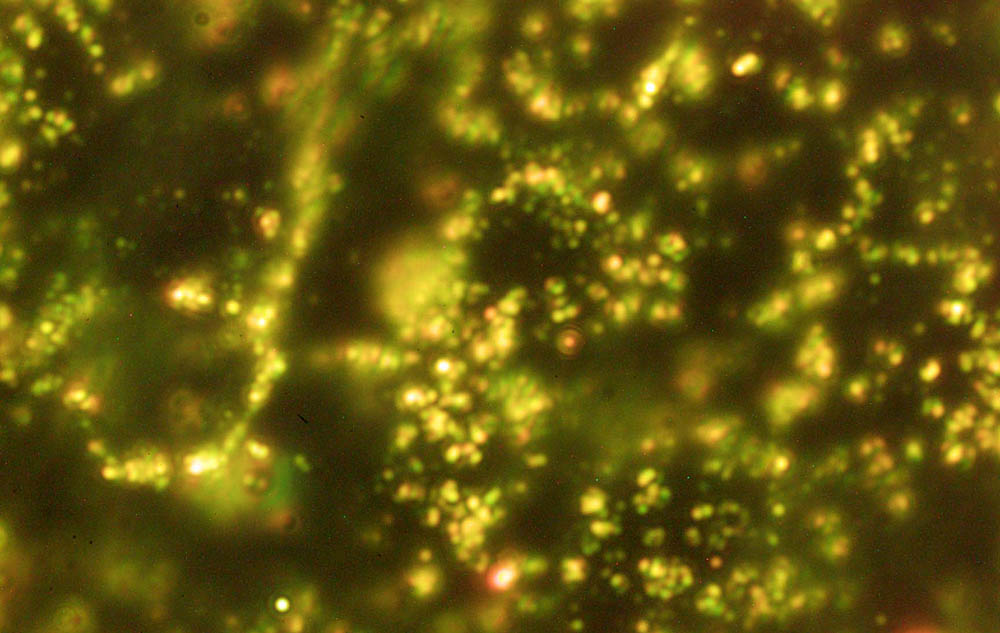

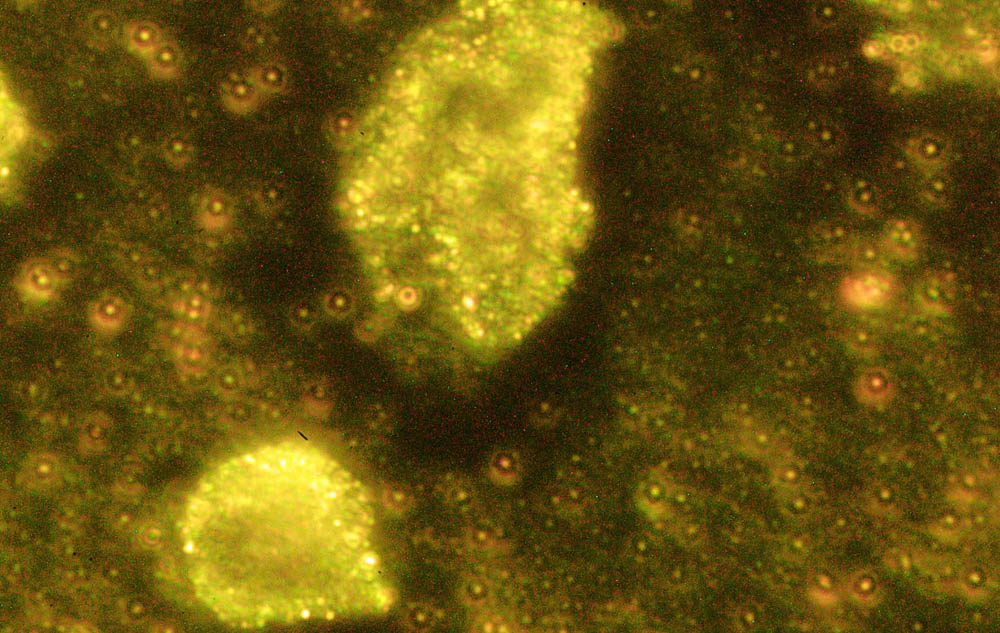

[Image: From the video, which appears below, showing the  [Image: Gold nanoparticles, courtesy of

[Image: Gold nanoparticles, courtesy of  [Image: Gold nanoparticles, courtesy of

[Image: Gold nanoparticles, courtesy of

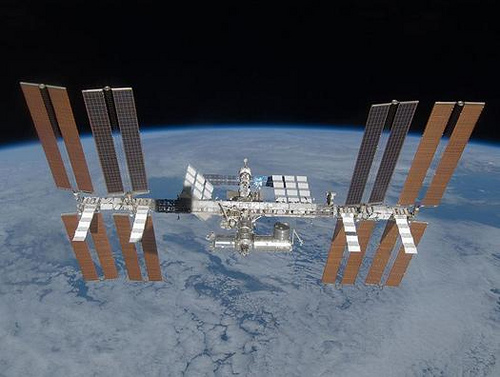

[Image: The International Space Station, courtesy of

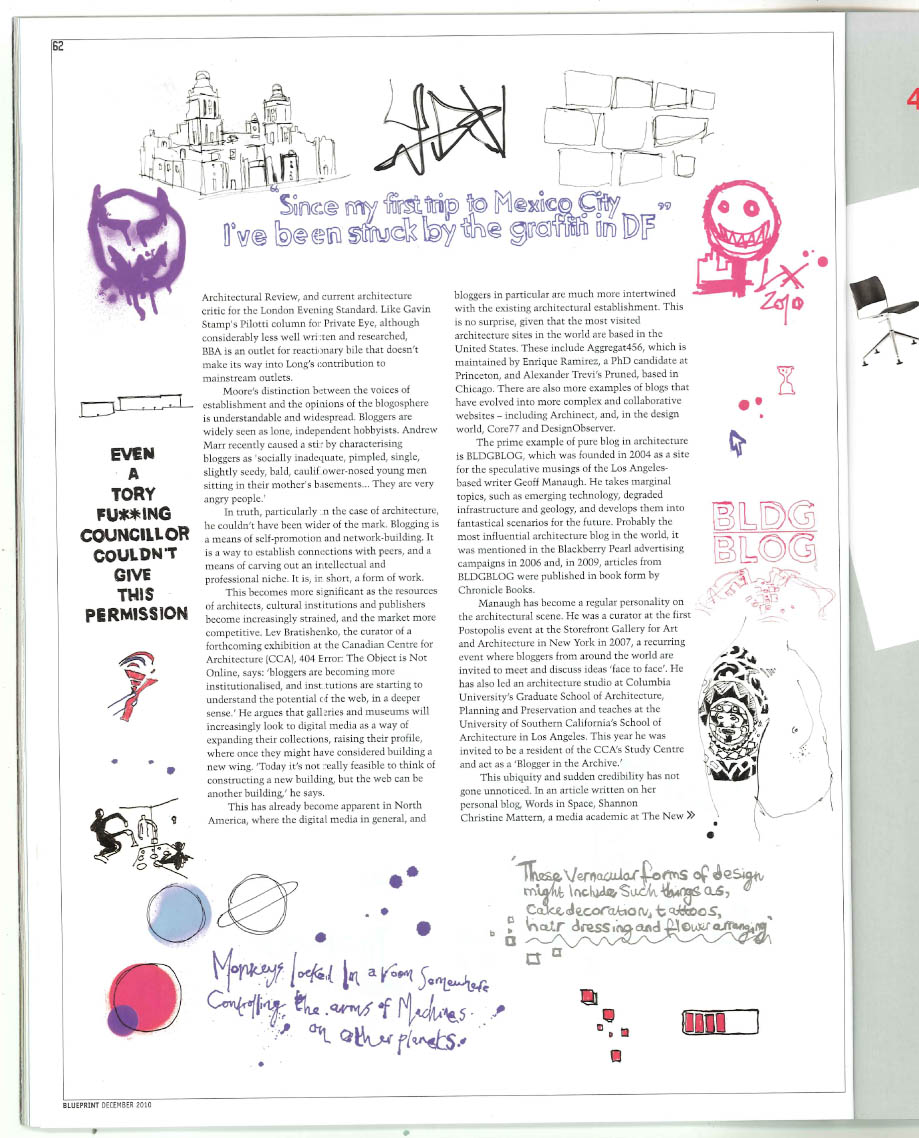

[Image: The International Space Station, courtesy of  [Image: Mars rover and its gadgets, courtesy of

[Image: Mars rover and its gadgets, courtesy of  [Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of  [Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of  [Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of  [Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of

[Image: “The New Establishment” by Peter Kelly, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The harp-like cabled insides of a New York bridge footing interior, courtesy of the

[Image: The harp-like cabled insides of a New York bridge footing interior, courtesy of the

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: From Gordon Matta-Clark’s

[Image: From Gordon Matta-Clark’s

[Image: Honey drips from the electrical sockets of a home in California; courtesy of

[Image: Honey drips from the electrical sockets of a home in California; courtesy of  [Image: A close-up of the honeycombs now tormenting a family in California; courtesy of

[Image: A close-up of the honeycombs now tormenting a family in California; courtesy of

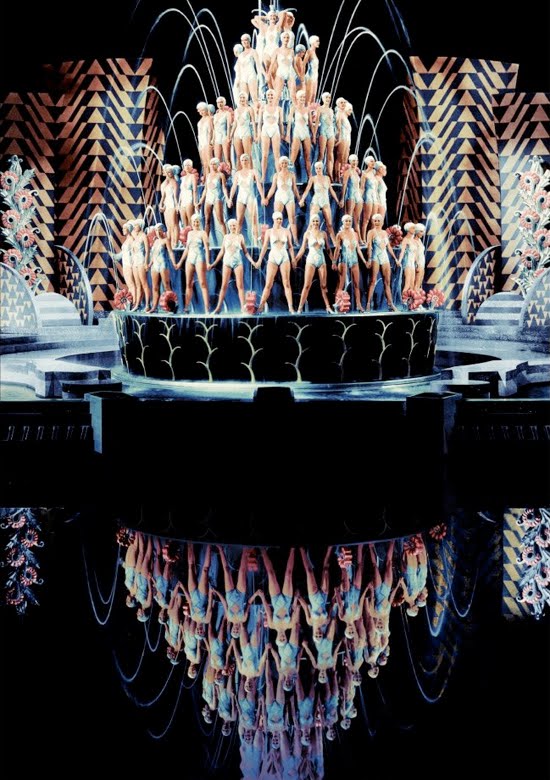

[Image: A mountainous display of women closely choreographed with water by Busby Berkeley, via Alexander Trevi’s

[Image: A mountainous display of women closely choreographed with water by Busby Berkeley, via Alexander Trevi’s  [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “