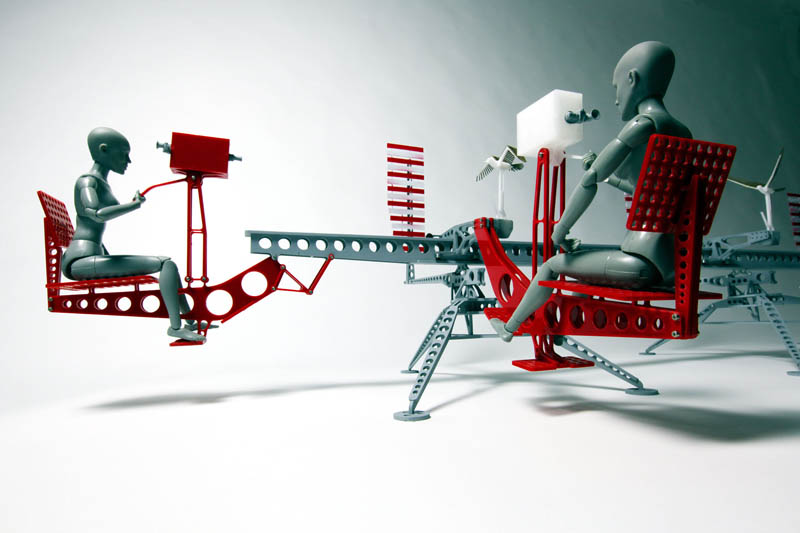

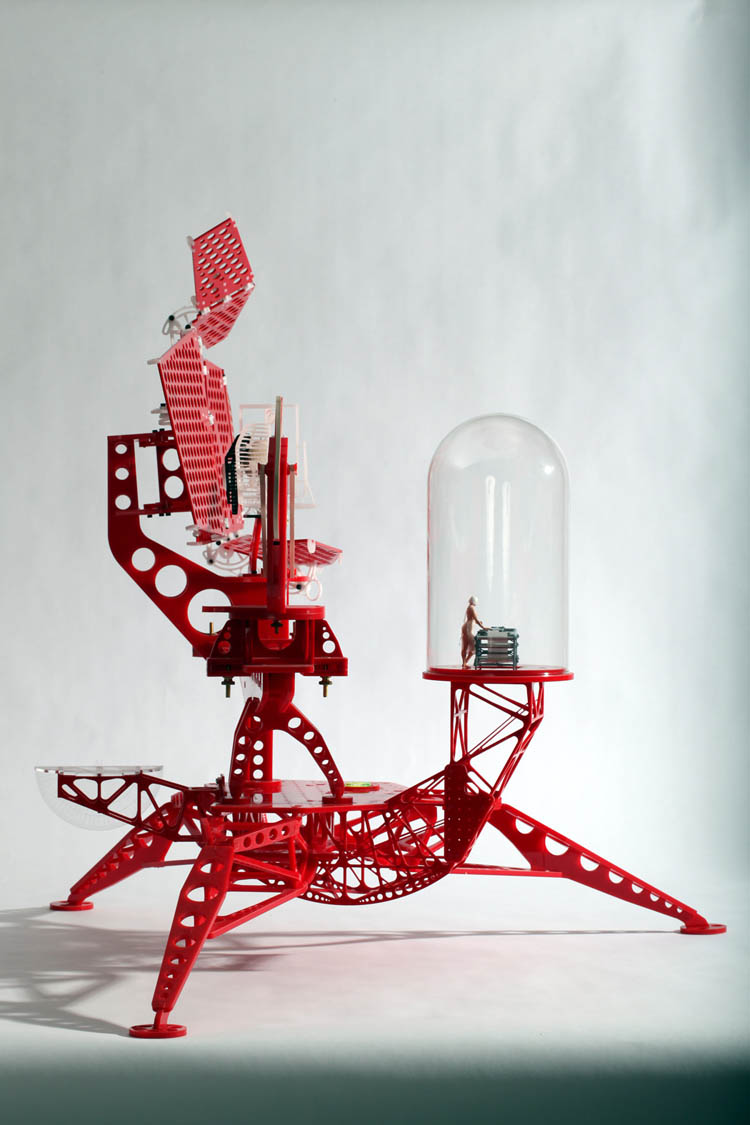

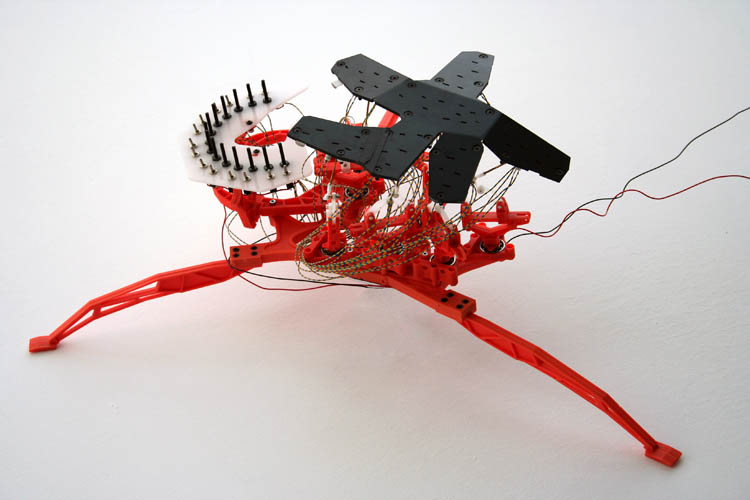

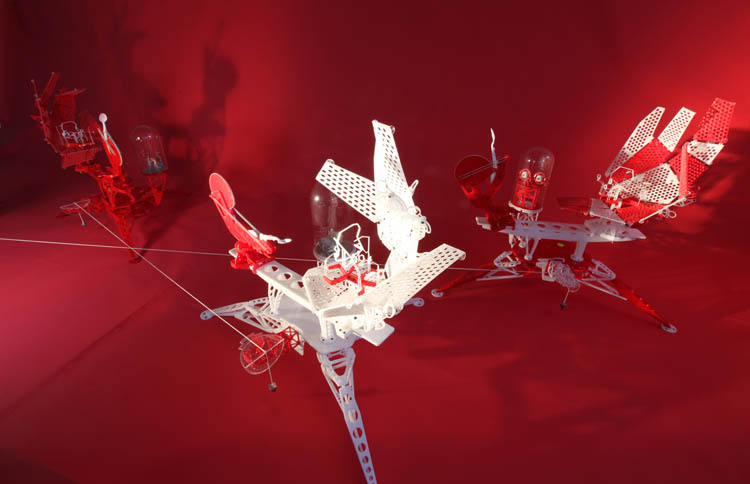

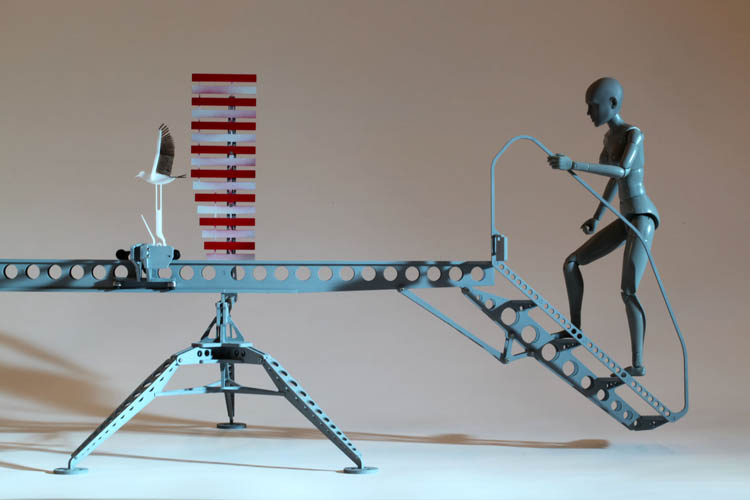

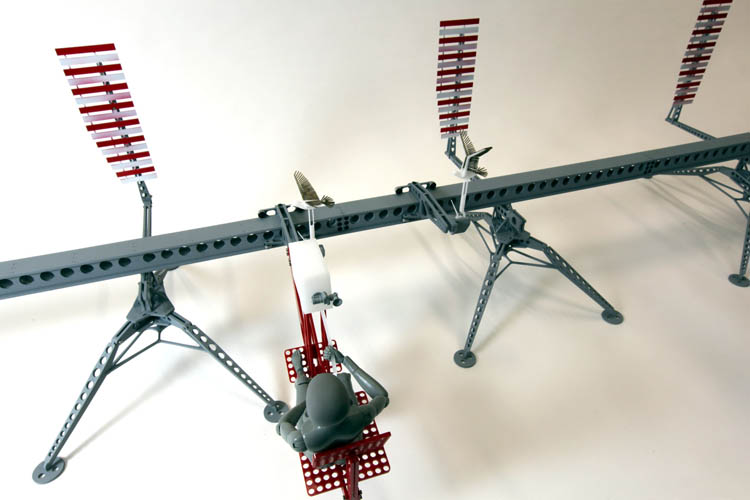

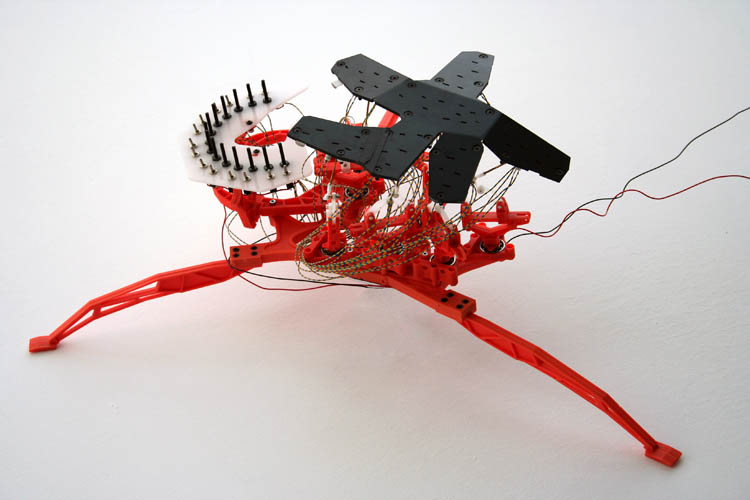

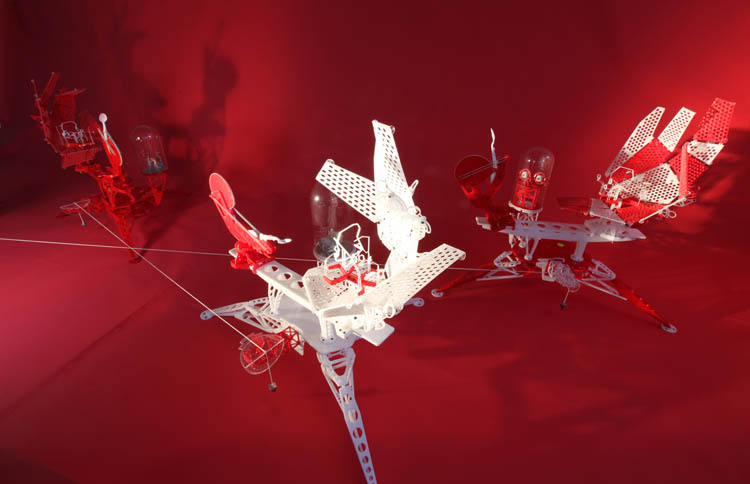

[Image: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

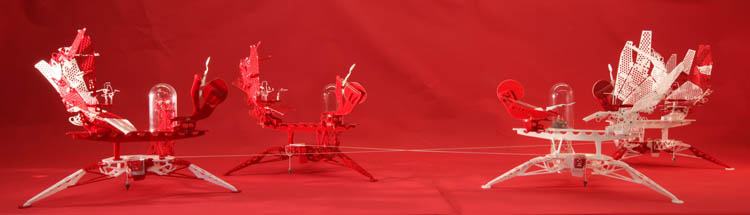

[Image: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

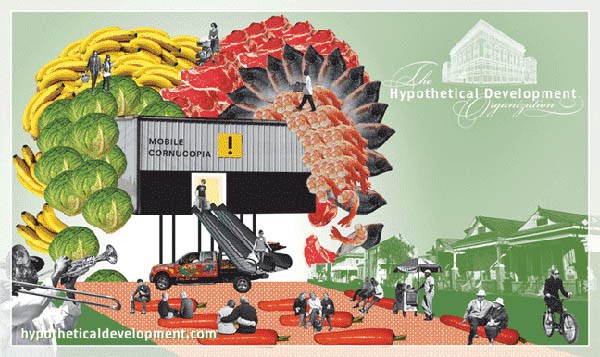

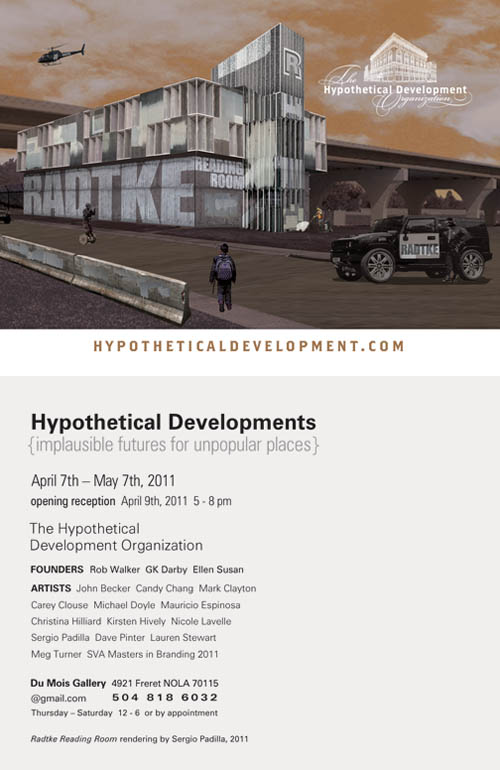

Fabricate is underway over in London, wrapping up in only a few hours (read a bit more about it here).

One of the conference’s many speakers is Nat Chard, from the University of Manitoba, who recently got in touch with some fantastic project images, showing mechanisms and devices of various functions and scales.

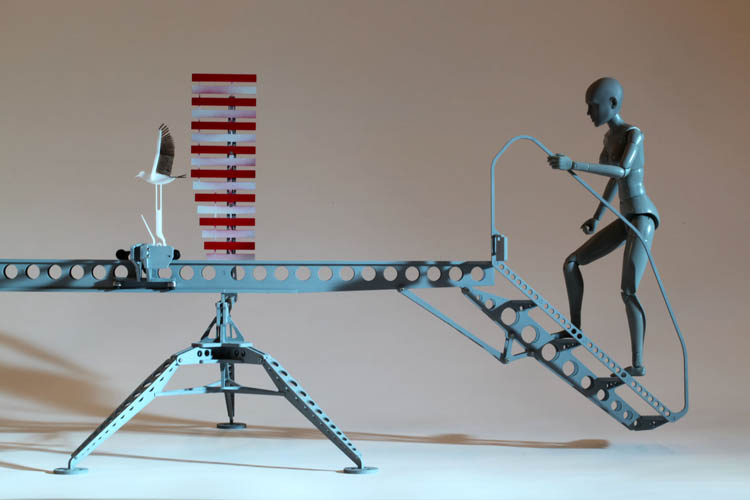

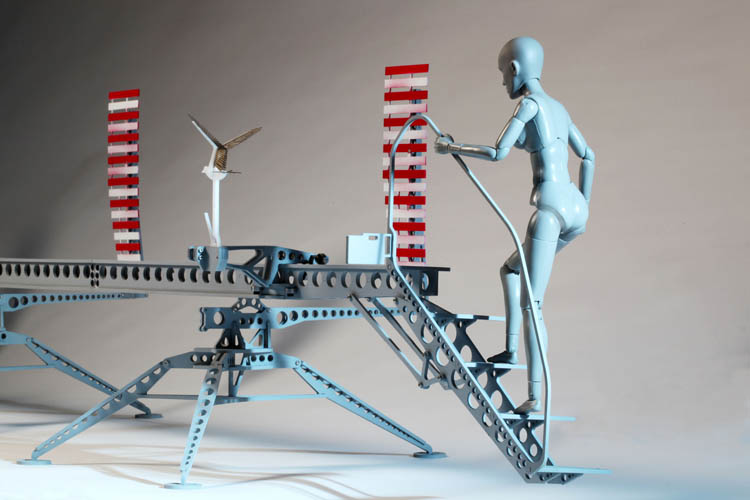

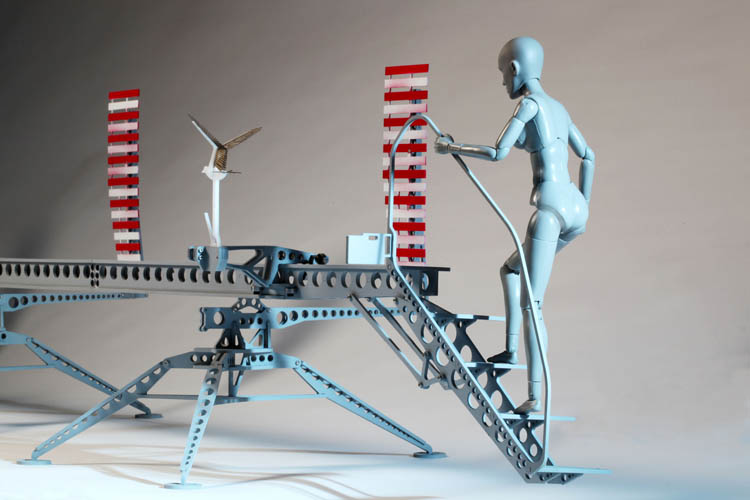

[Images: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

[Images: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

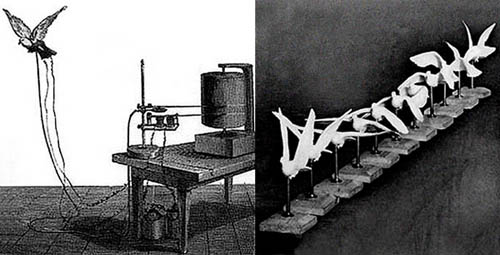

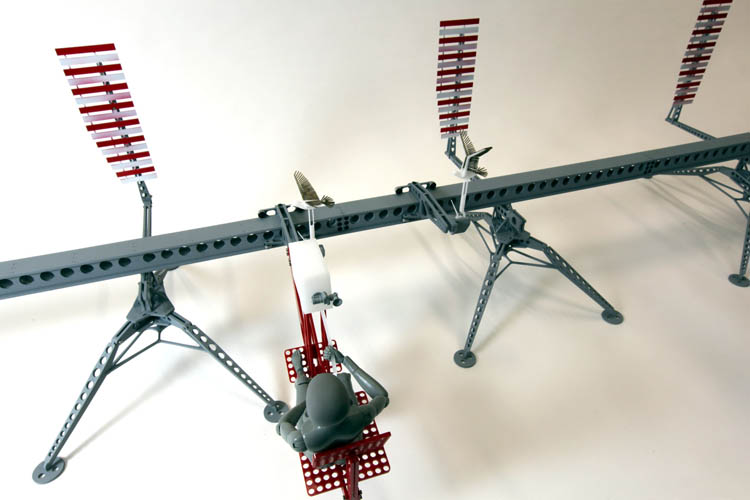

The first project seen here is the “Bird Automata Research Test Track.” It’s a spatial condensation and narrative reenactment of early attempts to photograph the anatomical movements associated with bird flight.

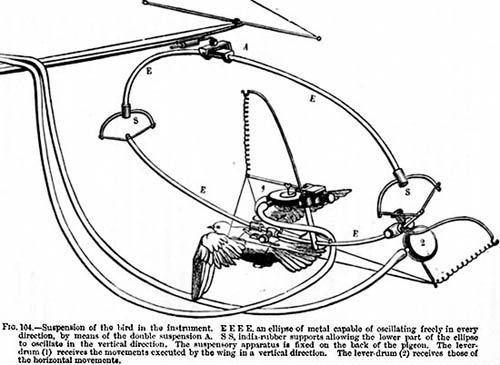

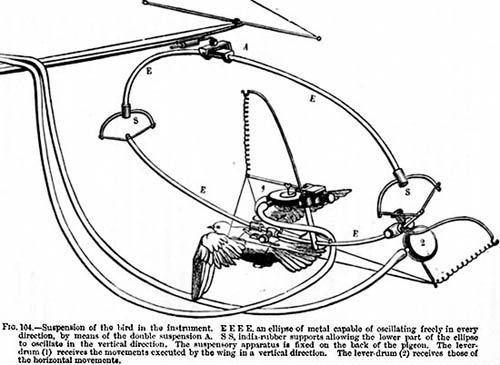

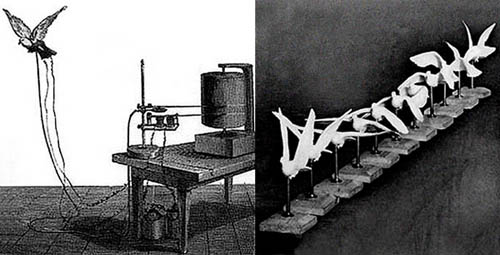

The set-up is a reference to the work of early artist-scientists such as Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, who sought to develop a technical means for analyzing physiological activity as a series of discrete, individual moments—or bodily freeze frames, if you will—using chronophotography.

[Image: A chronophotograph by Étienne-Jules Marey].

[Image: A chronophotograph by Étienne-Jules Marey].

As Jussi Parikka describes this in his recent book Insect Media, for late 19th-century and early 20th-century scientists, animal life represented “a microcosmos of new movements, actions, and perceptions”—it was seen as “something akin to a foreign planet of perceptions waiting to be excavated and reproduced.”

Whole new branches of technology were therefore developed in order to record and study how these unfamiliar anatomies interacted with the surrounding environment.

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography].

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography].

Chard’s bird track is thus an exploration of “representational stop animation… witnessed by researchers from two camera positions.” But the birds are not natural, living creatures; they are automata, machines: “A researcher tracks one of the birds in elevation, the other camera is sited at the end of the track watching the approaching birds. There is a stair cantilevered off the start of the track to allow access to set up the automata for a flight.”

[Images: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

[Images: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

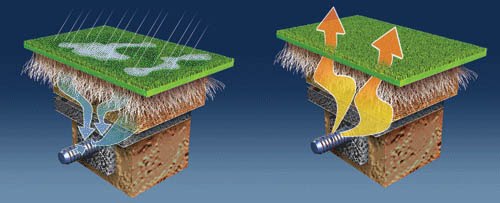

The spatial implications of chronophotography—which visually shatters the passage of time into a series of discrete moments extracted from an event-sequence of otherwise unfixed length and duration—leads to a reference, in a text on Chard’s website, to the fact that criminologists, physicists, and even paranormal investigators all also began to use “the emerging potential of photography to further their research.” In the process, those researchers “developed new sorts of architecture particular to the demands and opportunities of the medium and the way they were using [them]. There are many research institutions that display the emergence of a new architecture with very little typological precedent.”

I might refer to this instead not as architecture, though, but as spatial equipment for the measurable demarcation of fixed events. Or, if it is architecture, it is architecture as a piece of gear—a device, an instrument—that lets you measure the very thing it simultaneously helps set into motion.

[Image: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

[Image: From the “Bird Automata Research Test Track” by Nat Chard].

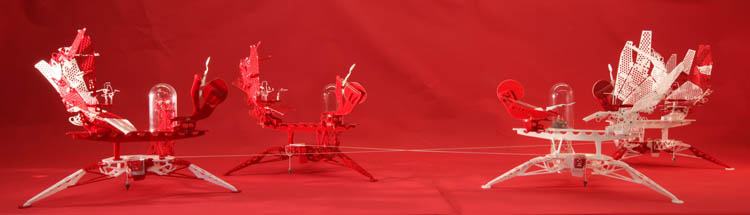

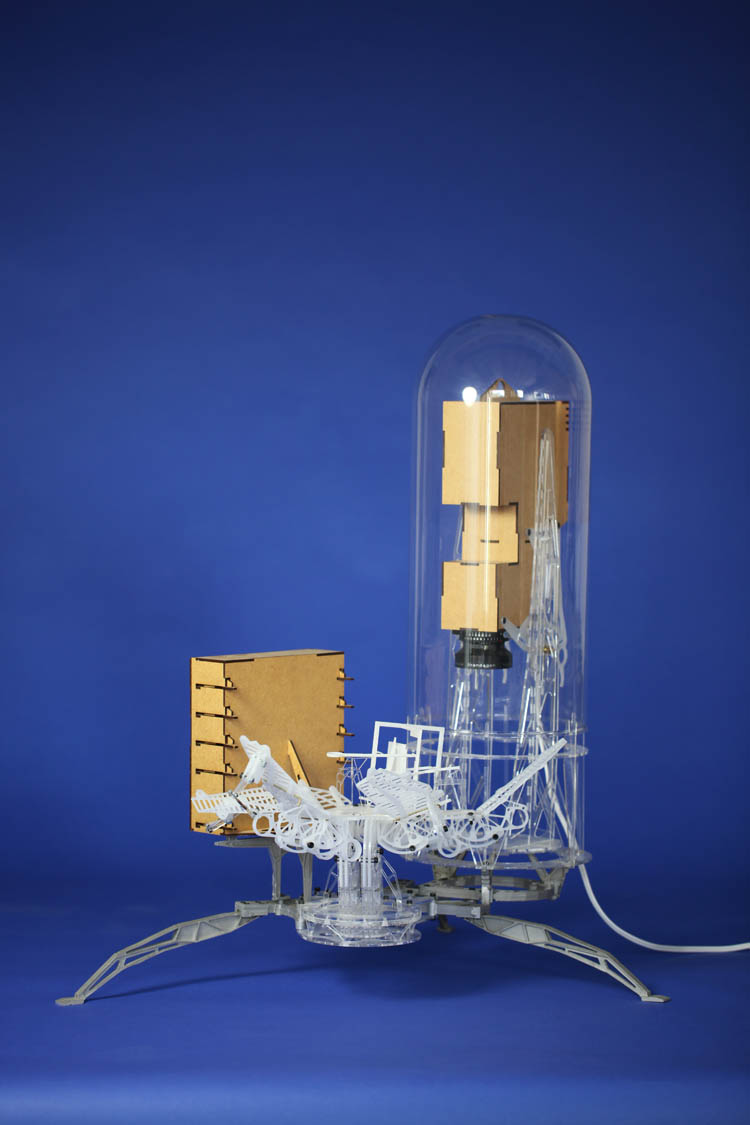

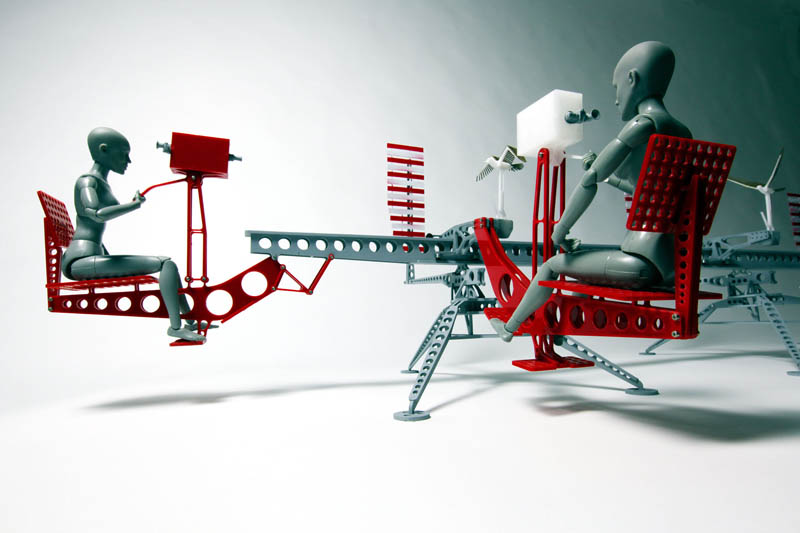

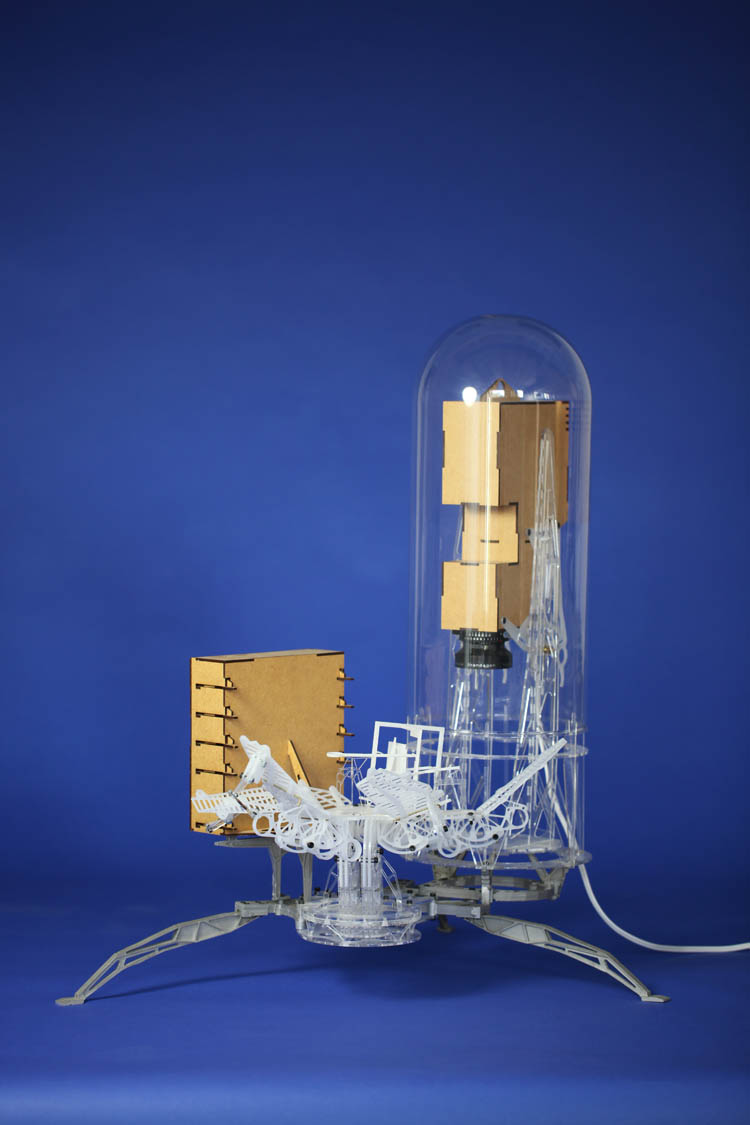

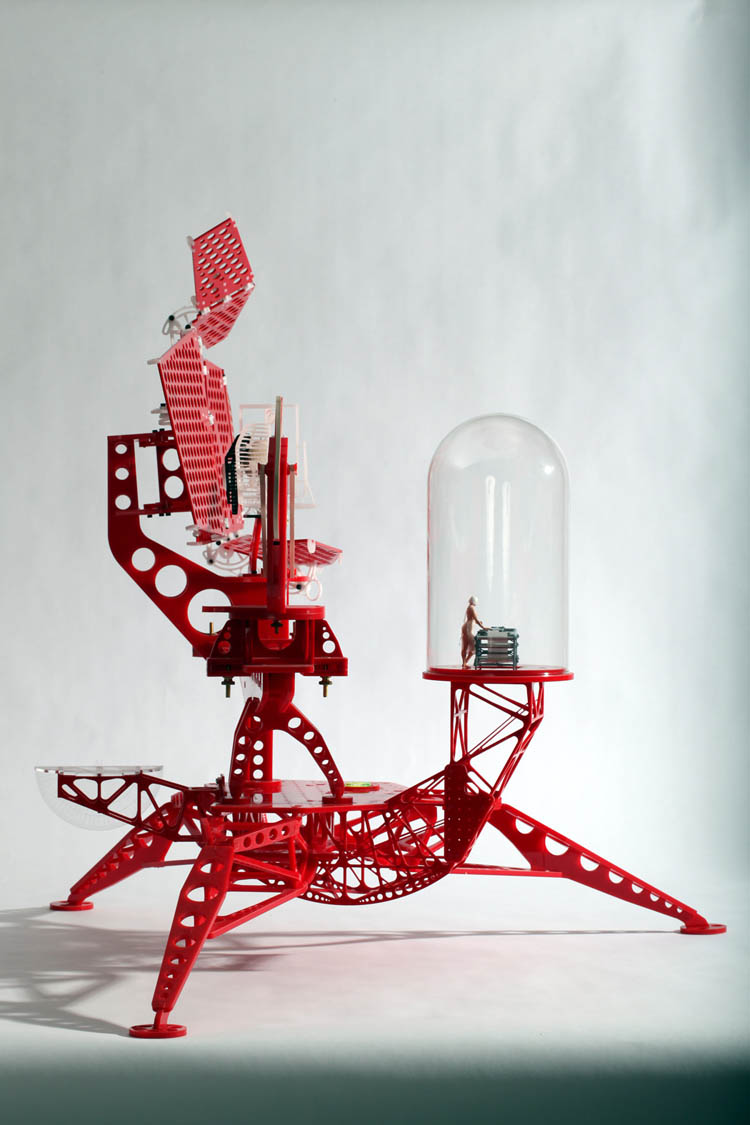

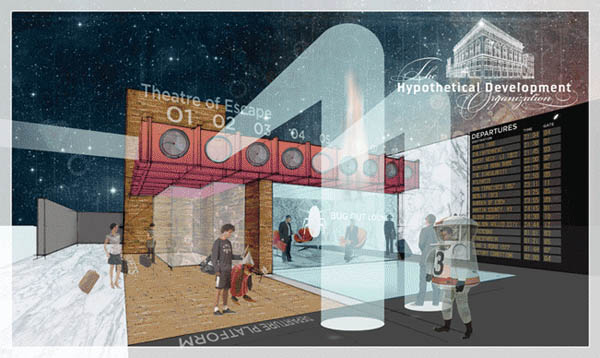

In any case, these ideas also animate Chard’s other, ongoing work: designing “variable picture plane drawing instruments” that graphically record spatial events.

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

They are optical devices that seem to flicker in and out of phase with themselves—little stage-sets that whir, self-camouflage, and take photos of their own future repositions and alterations.

Here, where we see that the equipment is actually photographing itself, I’m reminded of Edward Gordon Craig, a stage-set designer (and the son of an architect), whose “architectonic scenery,” as M. Christine Boyer describes it in The City of Collective Memory, turned the architectural backdrops themselves into the only action an audience was meant to watch, even proposing the elimination of actors altogether.

Craig “proposed that a stage in which walls and shapes rose up and opened out, unfolded or retreated in endless motion could become a performance without any actors,” Boyer writes. “The stage thus became a device to receive the play of light rhythmically, creating an endless variety of mobile cubic shapes and varying spaces. Deep wells, stairs, open spaces, platforms, or partitions created a stage of complete mobility, which Craig believed appealed to the imagination.”

The fascinating thing here is the idea of “a performance without any actors”—it would be pure space, pure architecture, pure equipment, pure device.

You’d simply sit in the dark and watch mechanized stage sets endlessly self-transforming.

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

Chard sent along parts of a still in-process essay that will soon be published in an issue of AD, edited by architect Bob Sheil, of sixteen*(makers), whose “probe field” project was featured on BLDGBLOG back in December.

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

Chard’s essay throws a variety of ideas into the mix, including the mystical (and unfortunately nonexistent) technology of “thoughtography,” i.e. the direct translation of thoughts into photographic images; the myth of the “genius sketch,” an image produced by someone (or, as his work intriguingly suggests, something) uniquely qualified and technically skilled enough to pull off instantaneously perfect acts of visual representation; and the geometric difficulties of representing 3D urban space on 2D surfaces, specifically looking at back at the history of drawing and surveying equipment, with references to the trigonometry of modern aerial bombers and Renaissance artillerymen, both of whom relied upon precise spatial calculations in order to map the targets that they would then set about trying to destroy.

At the heart of all these examples is the trick—the magic, one might say—of spatial representation: how to distill, translate, carry across, or otherwise re-enliven something from one field or context into another.

Chard’s devices are spatial equipment that document the very places they also frame and help define.

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

Chard’s machines are surprisingly playful—indeed, almost toylike—inhabited by small human figures and seemingly ready for mass-assembly (which would be amazing: imagine a generation of children raised not on Lincoln Logs but on Chard Devices, rewiring kids’ brains through the toys they play with).

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

The issue of AD edited by Bob Sheil, featuring Chard’s essay, should be out at some point in the near future, so keep your eyes peeled for that. In the meantime, I’ve posted some images of Chard’s work to give you a sense of the project’s ongoing directions and research possibilities.

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by Nat Chard].

Until then, check out Nat Chard’s website for a bit more info, or check out his book Drawing Indeterminate Architecture, Indeterminate Drawings of Architecture (though I should note that I have not yet seen a copy myself).

[Image: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson].

[Image: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson].

[Images: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson].

[Images: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson]. [Image: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson].

[Image: From Canal Street Cross-Section by Alan Wolfson].

[Image: From the “

[Image: From the “

[Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image: A chronophotograph by

[Image: A chronophotograph by

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography].

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography]. [Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image: From the “

[Image: From the “ [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by  [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by  [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: An abandoned golf course leaves traces in the landscape in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: An abandoned golf course leaves traces in the landscape in northern Los Angeles]. [Image: The system goes from suck to blow; images courtesy of

[Image: The system goes from suck to blow; images courtesy of  [Image: A path originally meant to follow a now-abandoned golf course in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: A path originally meant to follow a now-abandoned golf course in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ But there are many ways in which the

But there are many ways in which the

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

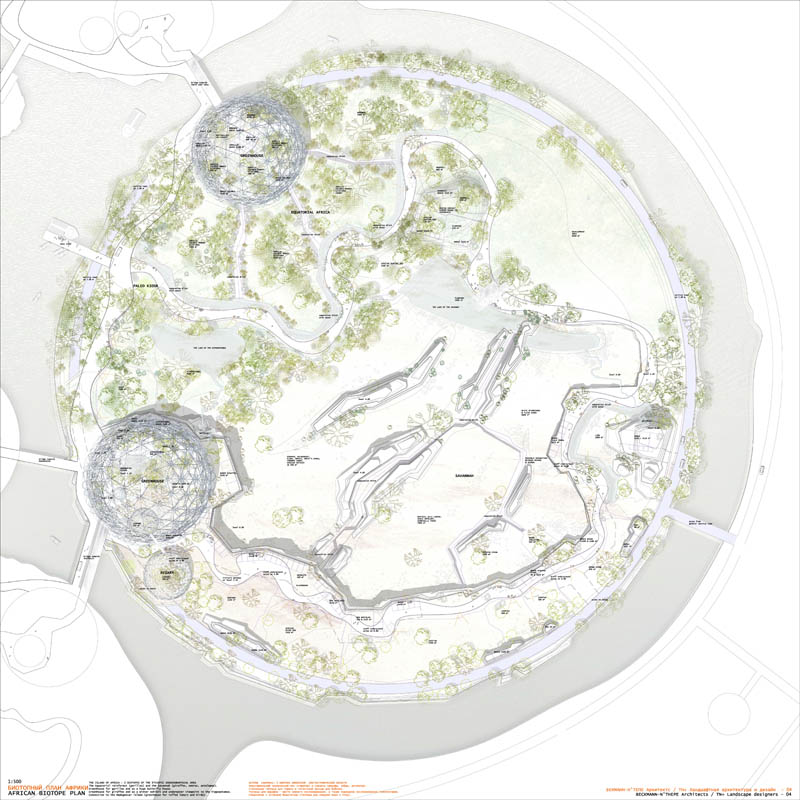

[Images: From a design for a zoo in St. Petersburg, Russia, by

[Images: From a design for a zoo in St. Petersburg, Russia, by  [Image: An archipelagic zoological park in St. Petersburg by

[Image: An archipelagic zoological park in St. Petersburg by

[Images: A future zoo in St. Petersburg by

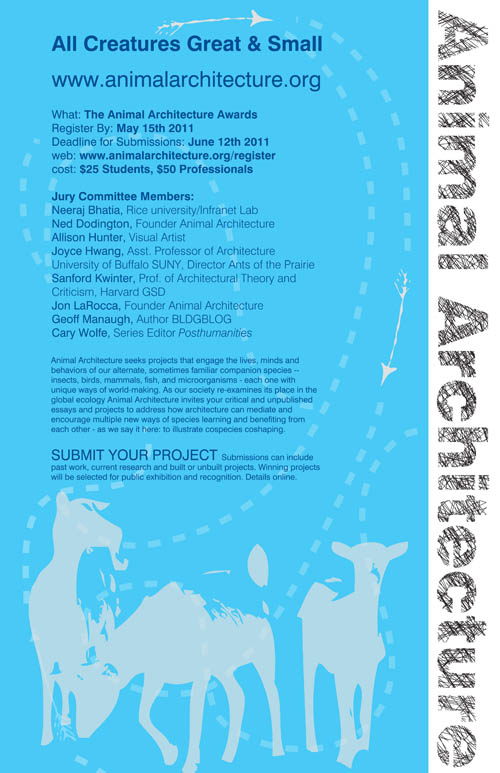

[Images: A future zoo in St. Petersburg by  In any case, there are so many directions to go with this discussion of “animal architecture”—theoretical, practical, speculative, critical, and otherwise—that I can’t wait to see what sort of things are submitted to the Animal Architecture project. Register by 15 May 2011 to submit your own essays and designs.

In any case, there are so many directions to go with this discussion of “animal architecture”—theoretical, practical, speculative, critical, and otherwise—that I can’t wait to see what sort of things are submitted to the Animal Architecture project. Register by 15 May 2011 to submit your own essays and designs.

[Images: A linear wooden forest instrument playing Bach, by

[Images: A linear wooden forest instrument playing Bach, by

[Image: Tokyo at night, courtesy of NASA’s

[Image: Tokyo at night, courtesy of NASA’s

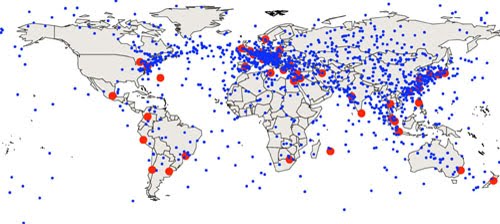

[Image: Global map of “optimal intermediate locations between trading centers,” based on the earth’s geometry and the speed of light, by

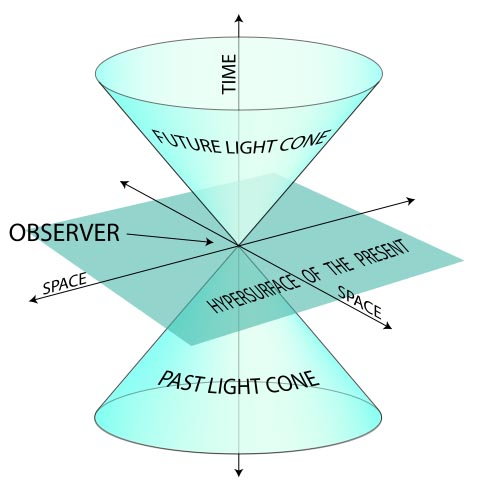

[Image: Global map of “optimal intermediate locations between trading centers,” based on the earth’s geometry and the speed of light, by  [Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a “light cone,” courtesy of

[Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a “light cone,” courtesy of  [Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic

[Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image: