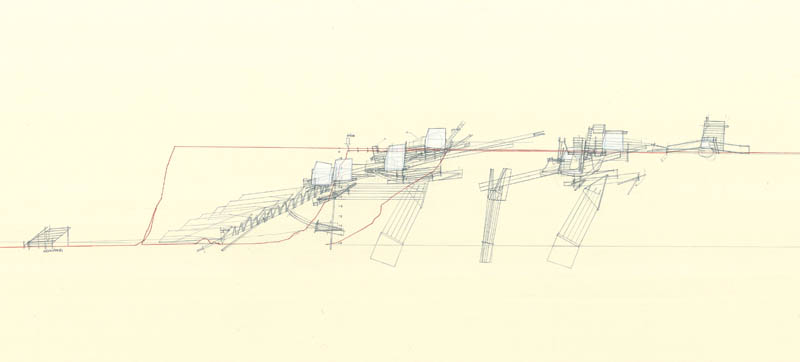

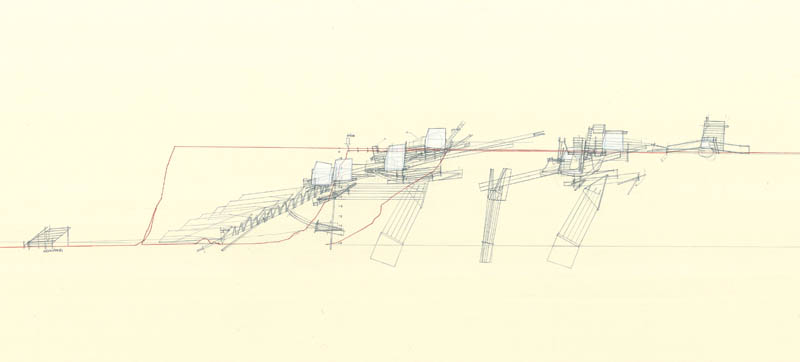

[Image: “Retreating Village” by Smout Allen, a mobile settlement for a collapsing landscape].

[Image: “Retreating Village” by Smout Allen, a mobile settlement for a collapsing landscape].

For the past few months, I have been working behind the scenes here on something that I am finally able to announce: starting tonight, and lasting for the next seven days, I will be helping to lead a Los Angeles-based design “super-workshop” with a spectacular line-up of participants.

Mark Smout and Laura Allen of Smout Allen & the Bartlett School of Architecture, along with 14 students; David Benjamin of The Living, along with 6 of his students; and the Arid Lands Institute in Burbank, California, along with 12 students will be here in Los Angeles, participating in a solid week of intensive workshops, discussions, site visits, design challenges, hikes, symposia, dinners, presentations, and crits.

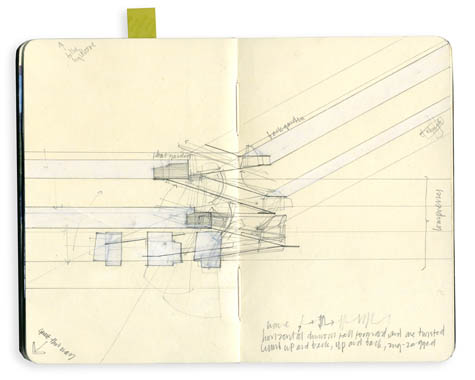

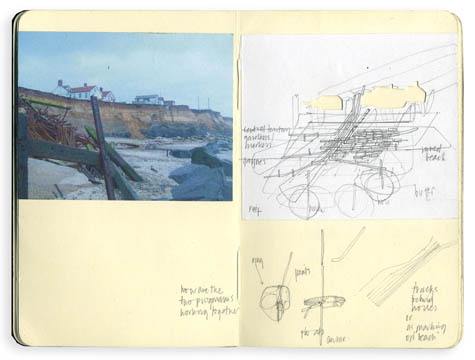

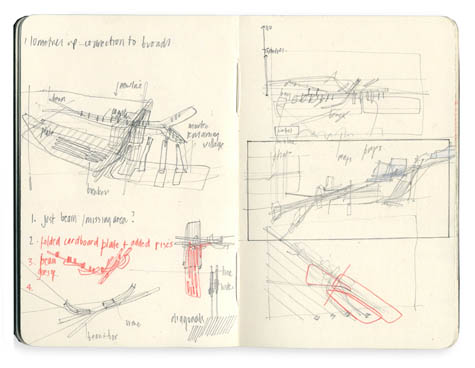

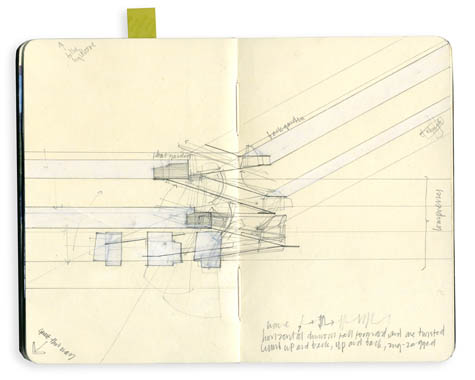

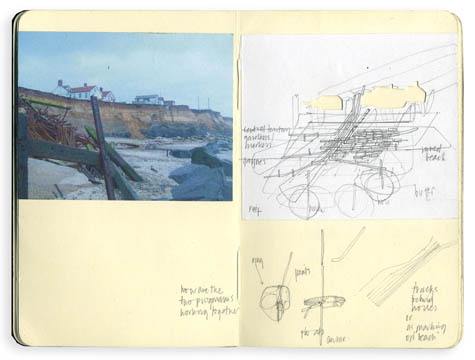

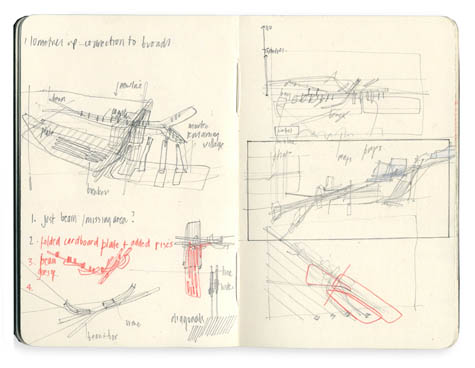

[Images: Sketches by Smout Allen].

[Images: Sketches by Smout Allen].

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Smout Allen, David Benjamin, and the Arid Lands Institute will be joined in this collaborative, multi-institutional undertaking by:

—David Gissen, California College of the Arts/Author of Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (htcexperiments.org)

—Matthew Coolidge and Sarah Simons, Center for Land Use Interpretation (clui.org)

—Christopher Hawthorne, Architecture Critic, Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

—Elizabeth Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse, Smudge Studio/Friends of the Pleistocene (smudgestudio.org/fopnews.wordpress.com)

—Ed Keller, AUM Studio/Parsons, New School for Design (aumstudio.org)

—Liam Young, Architectural Association/Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today (tomorrowsthoughtstoday.com)

—Alex Robinson, Office of Outdoor Research (orscapes.com)

—Emily White and Lisa Little, Layer (layerla.com)

—Nicola Twilley, Edible Geography/GOOD (ediblegeography.com/good.is)

—Christian Chaudhari (cargocollective.com/ccd)

—Tim Maly, Quiet Babylon (quietbabylon.com)

Getting this many people to Los Angeles has also been made possible in part with the generous support of Virgin America.

[Images: From Living Light by The Living].

[Images: From Living Light by The Living].

The super-workshop will be run in close parallel to the themes of a forthcoming exhibition that I am in the process of curating for the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, called Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices, and Architectural Inventions. That exhibition—on display from August 2011 to Spring 2012—has received grants from the Graham Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Needless to say, I am unbelievably excited about the exhibition and will be posting more about it as the year develops.

In brief, both the exhibition and this week’s super-workshop will examine how landscapes and our perceptions of them can be radically transformed by architecture, technology, and design. Specifically, participants and exhibitors alike will explore the multitude of ways through which landscapes can be read, cataloged, interpreted, mapped, and understood using specialty equipment, both speculative and real.

A central question of both the exhibition and the super-workshop will be how future tools of landscape investigation—new spatial devices on a variety of scales, from the inhabitable to the portable—can be imagined, designed, and fabricated. These include objects, models, prototypes, graphics, and speculative proposals, ranging from the physical to the digital, from the geological to the conceptual, from the felt to the heard, and from deep-time to the hand-made.

Workshop readings and discussions will include a mix of natural history, materials science, contemporary and historical landscape investigations, and an overview of existing landscape sensing & measurement technologies; we will also examine design projects by Smout Allen, The Living, Shin Egashira, Protocol Architecture, the United States Geological Survey, Caltech Robotics Lab, NASA’s Apollo Project, and more.

[Image: ”A crewman operates an Electrotape, circa late 1960s… a precise electronic surveying device that used microwaves to measure distance… It yielded centimeter accuracy over distances from 100 meters to 40 kilometers, and in all weather conditions, day and night. Two units were needed, one to send the signal and the other to receive it. A brass triangulation station marker is visible directly below the Electrotape.” Courtesy of the USGS].

[Image: ”A crewman operates an Electrotape, circa late 1960s… a precise electronic surveying device that used microwaves to measure distance… It yielded centimeter accuracy over distances from 100 meters to 40 kilometers, and in all weather conditions, day and night. Two units were needed, one to send the signal and the other to receive it. A brass triangulation station marker is visible directly below the Electrotape.” Courtesy of the USGS].

In the process, the workshop will maintain a strong focus on the built and natural landscapes of Los Angeles, a region prone to forest fires, drought, and flash floods, smog, landslides, and debris flows, climatic extremes, seismic activity, surface oil seepage, and methane clouds. These tacit connections with nature, even in the apparently manufactured terrains of greater Los Angeles, will be scrutinized.

To begin, workshop participants will visit a series of flood-control dams and landslide remediation structures in the San Gabriel Mountains; we will move from there to explore remnant urban oil fields, camouflaged drilling rigs, the La Brea Tar Pits, and other spatial side-effects of the region’s fossil fuel industry; we will study Southern California’s seismological sensing infrastructure; we will visit designers and engineers at the Caltech Robotics Lab; we will walk the streets of a once-thriving neighborhood that collapsed into the sea long ago due to relentless coastal erosion; and we will discuss the city’s troubled history with water diversion schemes—including dry lakes and dust storms—through a sustained look at the role of water in California’s landscapes of agri-business.

Recommended readings and references include but are not limited to:

—Smout Allen, Pamphlet Architecture 28: Augmented Landscapes (Princeton Architectural Press)

—Paul Thomas Anderson (dir.), There Will Be Blood

—Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (Vintage)

—Keller Easterling, Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and its Political Masquerades — Chapter 3 (MIT Press)

—Shin Egashira and David Greene, Alternative Guide to the Isle of Portland (Architectural Association)

—William L. Fox, Making Time: Essays on the Nature of Los Angeles (Shoemaker & Hoard)

—David Gissen, Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (Princeton Architectural Press)

—InfraNet Lab/Lateral Office, Pamphlet Architecture 30: Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism (Princeton Architectural Press)

—cj Lim, Devices: A Manual of Architectural + Spatial Machines (Architectural Press)

—John McPhee, Assembling California (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

—John McPhee, “Los Angeles Against the Mountains” in The Control of Nature (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

—Michael Novacek, Time Traveler: In Search of Dinosaurs and Ancient Mammals from Montana to Mongolia (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) — Chapters 1 and 10

—Fred Pearce, When the Rivers Run Dry: Water, The Defining Crisis of the Twenty-First Century (Beacon) — Chapters 1, 3, 6, 24, 27, 28, 30

—Roman Polanski (dir.), Chinatown

—Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water (Penguin)

—Kim Stringfellow, Greetings from the Salton Sea: Folly and Intervention in the Southern California Landscape, 1905–2005 (Center for American Places)

—Chris Taylor and Bill Gilbert, Land Arts of the American West (University of Texas Press)

—David Ulin, The Myth of Solid Ground: Earthquakes, Prediction, and the Fault Line Between Reason and Faith (Penguin)

Needless to say, I suspect some fantastic student work, conversations, and more will come out of the next seven days, and I will do my best to keep track of it all here on the blog. But if things fall quiet for a few days here, now you’ll know why.

Finally, stay tuned for information about a public event here in Los Angeles this coming weekend, bringing many of these participants together.

[Images: (top) “A helicopter makes access easy in southern Utah, circa early 1960s.” (bottom) “Scribing roads on a topographic map.” Courtesy of the USGS].

[Images: (top) “A helicopter makes access easy in southern Utah, circa early 1960s.” (bottom) “Scribing roads on a topographic map.” Courtesy of the USGS].

So thanks again to Virgin America for their generous support, and, of course, to all our participants. More information coming soon.

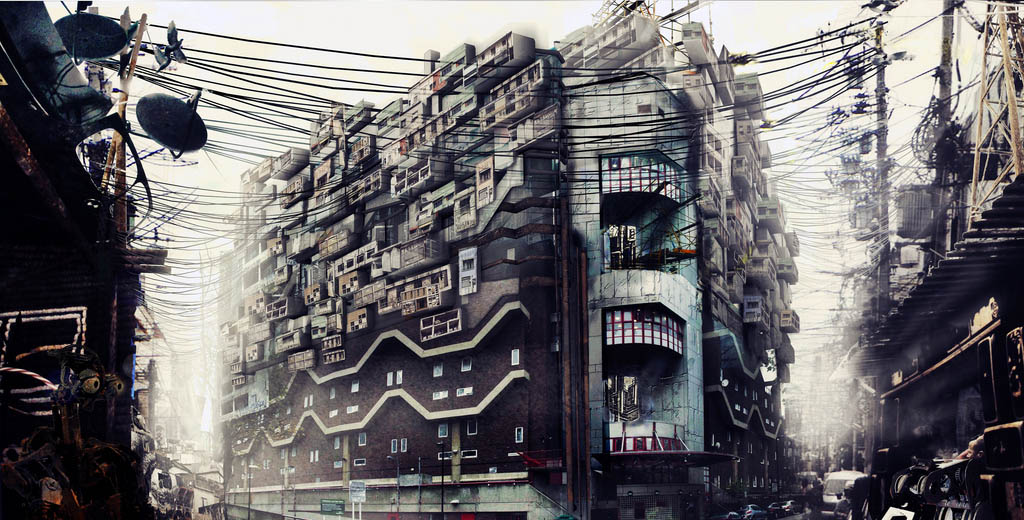

[Image: “Southwyck House,” “inhabited by London’s new robot workforce,” by Kibwe X-Kalibre Tavares of Factory Fifteen].

[Image: “Southwyck House,” “inhabited by London’s new robot workforce,” by Kibwe X-Kalibre Tavares of Factory Fifteen]. [Image: “Brixton High Street” by Kibwe X-Kalibre Tavares of Factory Fifteen].

[Image: “Brixton High Street” by Kibwe X-Kalibre Tavares of Factory Fifteen].

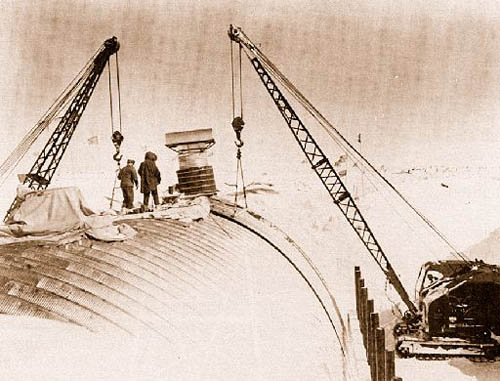

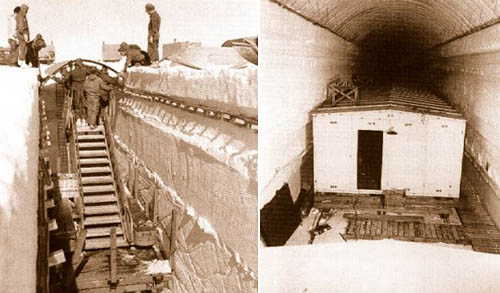

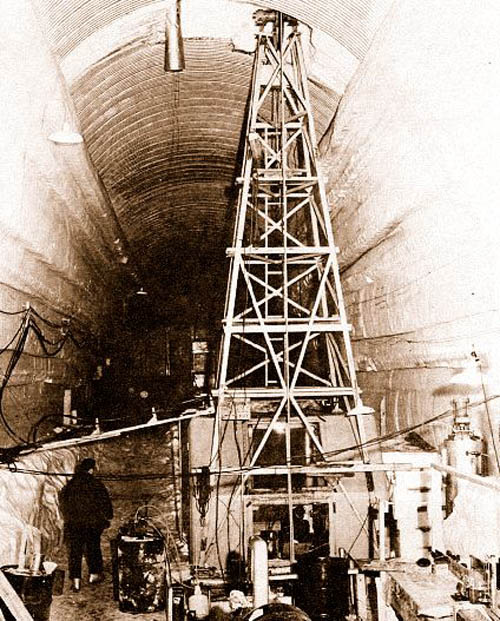

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

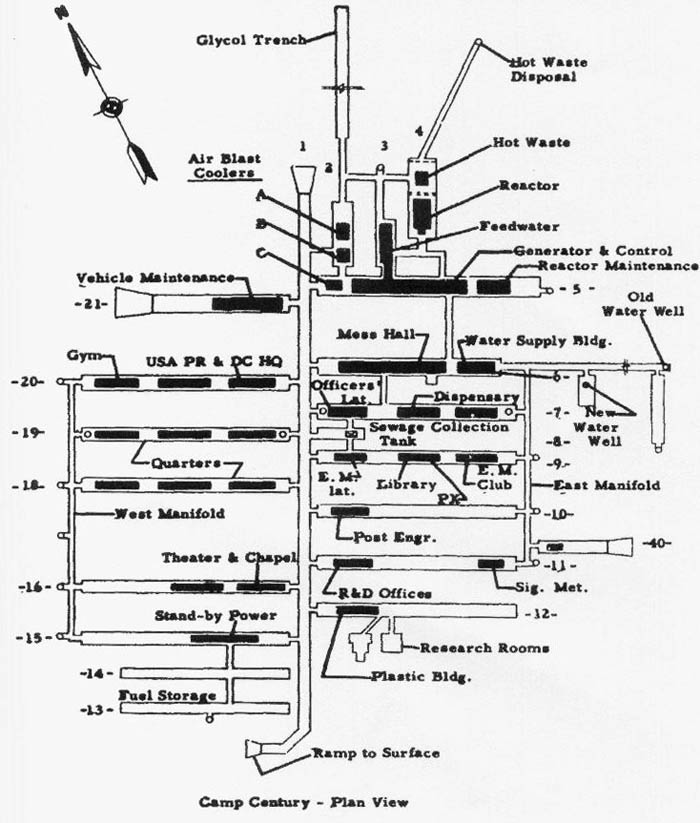

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via  [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

Specifically, the

Specifically, the

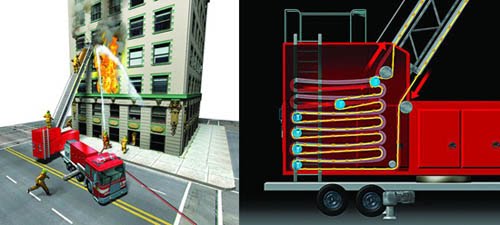

[Images: Illustrations by

[Images: Illustrations by

[Image: From a presentation by

[Image: From a presentation by

[Image: The electromagnetic infrastructure of Los Angeles; photo by the

[Image: The electromagnetic infrastructure of Los Angeles; photo by the  [Image: “Topping-out ceremony” at the Onkalo nuclear-waste sequestration site, Finland; photo by

[Image: “Topping-out ceremony” at the Onkalo nuclear-waste sequestration site, Finland; photo by

[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

[Image: A bubbling tar seep near Wilshire Boulevard].

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits].

[Images: Skulls and bones at the La Brea Tar Pits]. [Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: A “satellite tracking station” near the headwaters of the L.A. River]. [Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the

[Image: Learning about water infrastructure courtesy of the  [Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Image: The headwaters of the L.A. River].

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].

[Image: Super-workshoppers descend the Hansen Dam].  [Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

[Image: Debris basin at the top of Pine Cone Road].

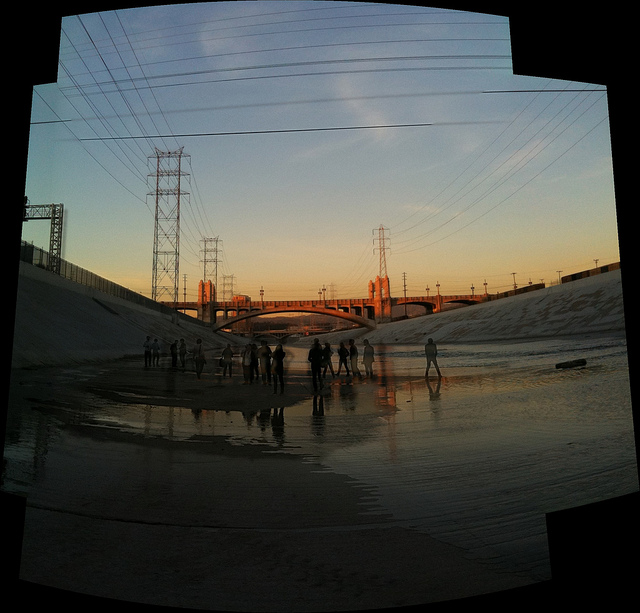

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].

[Images: The L.A. River at sunset].

[Image: “Retreating Village” by

[Image: “Retreating Village” by

[Images: Sketches by

[Images: Sketches by

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: ”A crewman operates an Electrotape, circa late 1960s… a precise electronic surveying device that used microwaves to measure distance… It yielded centimeter accuracy over distances from 100 meters to 40 kilometers, and in all weather conditions, day and night. Two units were needed, one to send the signal and the other to receive it. A brass triangulation station marker is visible directly below the Electrotape.” Courtesy of the

[Image: ”A crewman operates an Electrotape, circa late 1960s… a precise electronic surveying device that used microwaves to measure distance… It yielded centimeter accuracy over distances from 100 meters to 40 kilometers, and in all weather conditions, day and night. Two units were needed, one to send the signal and the other to receive it. A brass triangulation station marker is visible directly below the Electrotape.” Courtesy of the

[Images: (top) “A helicopter makes access easy in southern Utah, circa early 1960s.” (bottom) “Scribing roads on a topographic map.” Courtesy of the

[Images: (top) “A helicopter makes access easy in southern Utah, circa early 1960s.” (bottom) “Scribing roads on a topographic map.” Courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise unrelated temple complex in Indonesia].

[Image: An otherwise unrelated temple complex in Indonesia].

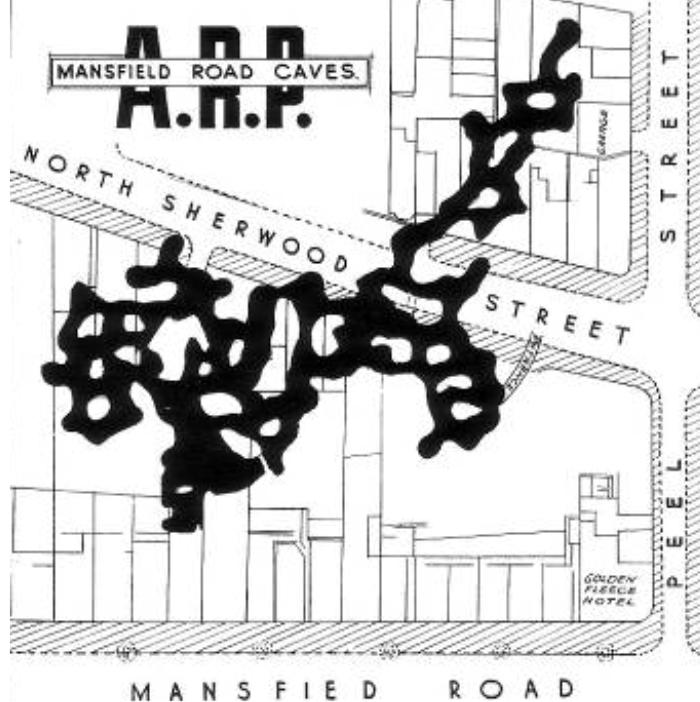

[Image: A 3D laser scan of the

[Image: A 3D laser scan of the  [Image: Plan of the

[Image: Plan of the