Some of my favorite architectural images of all time come from a series of photos taken by Fred R. Conrad for the New York Times, showing the remains of an 18th-century ship that was uncovered in the muddy depths of the World Trade Center site, a kind of wooden fossil, splayed out and preserved like a rib cage, embedded in the foundations of New York City.

[Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

[Images: Photos by Fred R. Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times].

Although it’s almost embarrassing to admit how much I think of this—hoping, I suppose, that some vast wooden fleet will someday be discovered beneath Manhattan, lying there in wait, disguised as basements, anchored quietly inside skyscrapers, masts mistaken for telephone poles, perhaps even slowly rocking with the tidal rise of groundwater and subterranean streams—it came to mind almost immediately while re-reading a short book by art historian Indra Kagis McEwen called Socrates’ Ancestor.

Really more of an etymological analysis of spatial concepts inherited from ancient Greece, from the idea of khôra to the myth of Icarus, McEwen’s book has at least two interesting moments, the first of which relates directly to ships.

[Image: Greek triremes at war, via Pacific Standard].

[Image: Greek triremes at war, via Pacific Standard].

“At one important point in its history,” she writes, “Athens literally became a fleet of ships.”

When Themistocles evacuated Athens in 481 B.C. in the face of the Persian threat, the entire city put out to sea, taking with it its archaion agalma [or cult statue] of Athena Polias. And when, according to Plutarch, a certain person said to Themistocles “that a man without a city had no business to advise men who still had cities of their own” Themistocles answered,

It is true thou wretch, that we have left behind us our houses and our city walls, not deeming it meet for the sake of such lifeless things to be in subjection; but we still have a city, the greatest in Hellas, our two hundred triremes.

That is, the city took to the waves, physically and literally abandoning solid ground—leaving the earth behind, we might say—to go mobile, en masse, cutting through the water like Armada from The Scar, novelist China Miéville‘s “flotilla of dwellings. A city built on old boat bones.” In The Scar, Miéville envisions “many hundreds of ships lashed together, spread over almost a square mile of sea, and the city built on them… Tangled in ropes and moving wooden walkways, hundreds of vessels facing all directions rode the swells.”

Incredibly, in the very origins of Western urbanism, this offworld—or at least offshore—scenario actually played itself out, with the evacuation and subsequent becoming-maritime of the entire city of Athens, Greece.

The whole city just picked up, left dry ground, and sailed off for the horizon.

Briefly, McEwen’s book has at least one other detail worth mentioning here: a comparison between ancient shipbuilding techniques and weaving—or, as she says, “the way ancient shipwrights assembled their craft is clearly analogous to the techniques of weaving. To edge-join planks with mortise-and-tenon joints is, essentially, to interlace pieces of wood.”

In the shipyard, planks laid in one direction were fastened to other planks by tenons that penetrated, or interlaced, the planks at right angles in order to bind them together. Similarly, on a loom, the warp threads (analogous to planks) extended in one direction are bound together by weft threads (analogous to tenons and pegs) traveling orthogonally, which interpenetrate the warp threads at right angles to make the cloth.

The word histos, she points out, which can mean “anything set upright, is at once the mast of a ship and a Greek loom… Histos or histion is the web woven on the loom, and histia also are sails.”

[Image: “The first builders wove their walls.” From Socrates’ Ancestor by Indra Kagis McEwen].

[Image: “The first builders wove their walls.” From Socrates’ Ancestor by Indra Kagis McEwen].

This was translated into an architectural technique, she suggests. Citing the historical conjecture of Vitruvius, who wanted to discover where and how architecture truly began, McEwen adds that “the first builders wove their walls… In Vitruvius’ anthropology, community is consolidated when people began to build: ‘And first, with upright forked props and twigs put between, they wove their walls.’ Vitruvius’ first structure is that of an upright Greek loom.”

That is, they “wove their walls” with wood—making some of the Western world’s earliest architectural structures, as McEwen summarizes, both the product of and identical with “an upright Greek loom.”

They were textiles—as were ancient Greek ships. Like floating pieces of oversized clothing woven together from fallen forests.

The ship, the building, the city: they are “a linked series of looms.”

I feel compelled to mention here that some of the most advanced techniques in architectural fabrication today involve, as it happens, a return to looms, or the 3D-weaving of architectural parts and spaces using, in some cases, technologies—such as carbon fiber weaving—borrowed from the automobile industry (as seen in the eye-popping video embedded above).

In any case, it is quite a heady thing to consider all this at once: vast looms at the southern tip of Manhattan, weaving in real-time an interlocking lacework of carbon fiber ship-buildings that depart immediately for the rising seas of the north Atlantic.

The city reveals its inner logic is not that of a grid but of a fleet—not landlocked buildings but patient ships—as silent streets peer out at the sea with longing.

(Vaguely related: Ground Conditions).

[Image: A carved sandstone model of the incredible walled fortress-city of

[Image: A carved sandstone model of the incredible walled fortress-city of  [Image: Model of Jaisalmer; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Model of Jaisalmer; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Monumentalizing mismeasurement in Ecuador; photoby

[Image: Monumentalizing mismeasurement in Ecuador; photoby  [Image: The grid arrives before the streets it surveys].

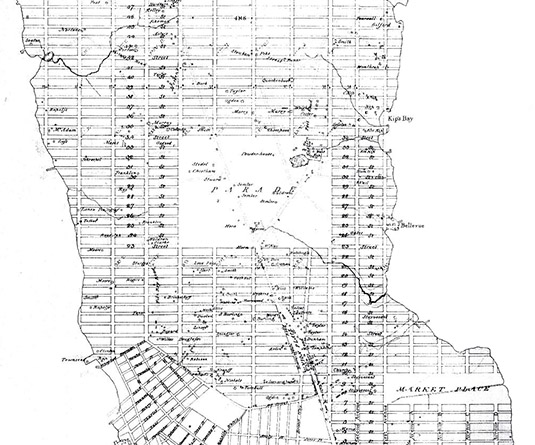

[Image: The grid arrives before the streets it surveys]. [Image: From Laura Kurgan’s

[Image: From Laura Kurgan’s

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

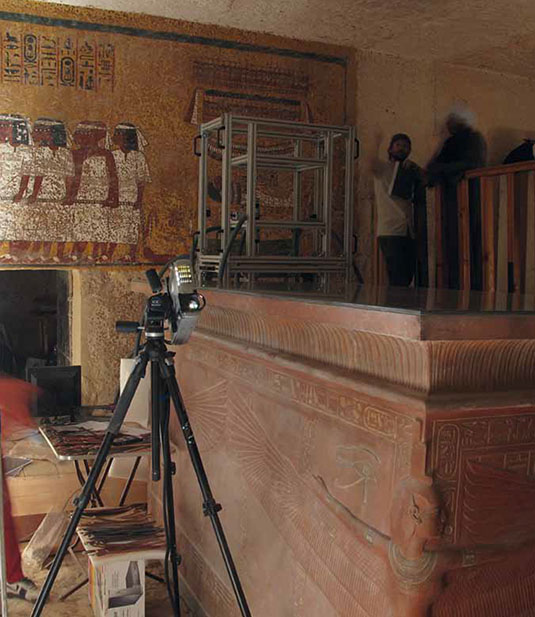

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the  [Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the  [Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the  [Image: Routing tomb details into polyurethane, courtesy of the

[Image: Routing tomb details into polyurethane, courtesy of the  [Image: One of the scanning set-ups used to “record” the tombs, courtesy of the

[Image: One of the scanning set-ups used to “record” the tombs, courtesy of the  [Image: Printing the facsimile, courtesy of the

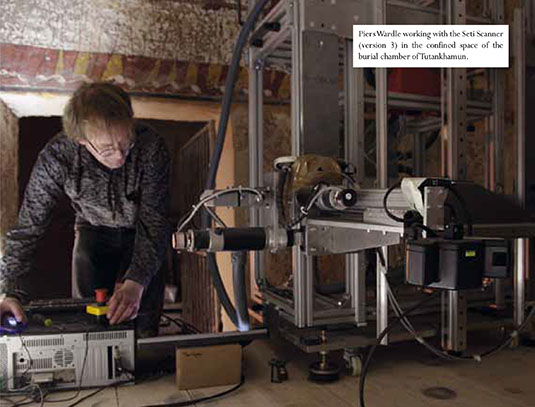

[Image: Printing the facsimile, courtesy of the  [Image: 3D-printed replicant cuneiform tablets by Hod Lipson and David Owen at the Cornell

[Image: 3D-printed replicant cuneiform tablets by Hod Lipson and David Owen at the Cornell

[Image: A robot strawberry harvester, courtesy of

[Image: A robot strawberry harvester, courtesy of  [Image: A banana-ripening room photographed by

[Image: A banana-ripening room photographed by  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: An otherwise only conceptually related photo by

[Image: An otherwise only conceptually related photo by

[Image: “Salvage Architecture” by production designer

[Image: “Salvage Architecture” by production designer

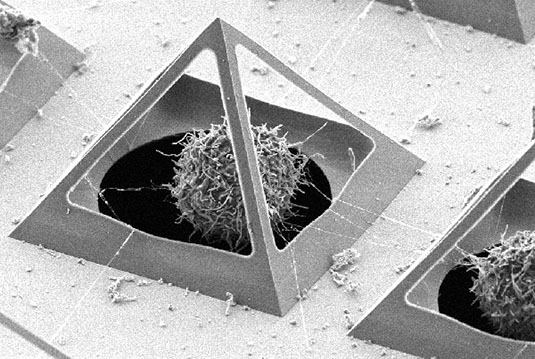

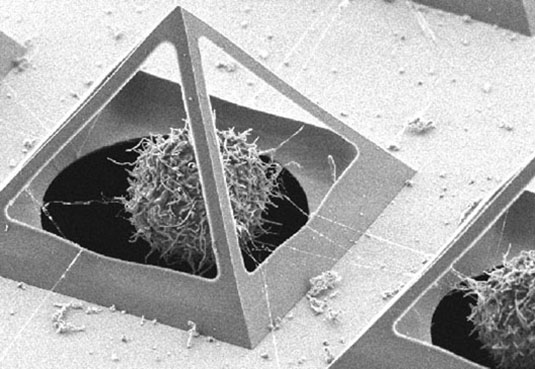

[Image: A pyramidal “cell trapping device,” via

[Image: A pyramidal “cell trapping device,” via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside

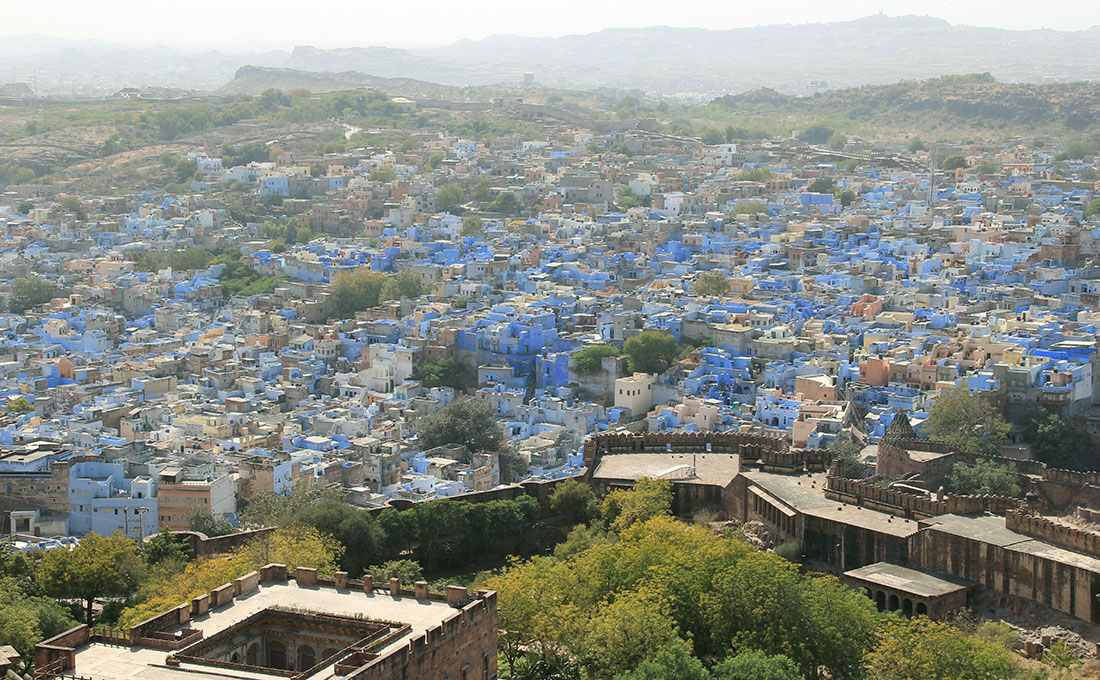

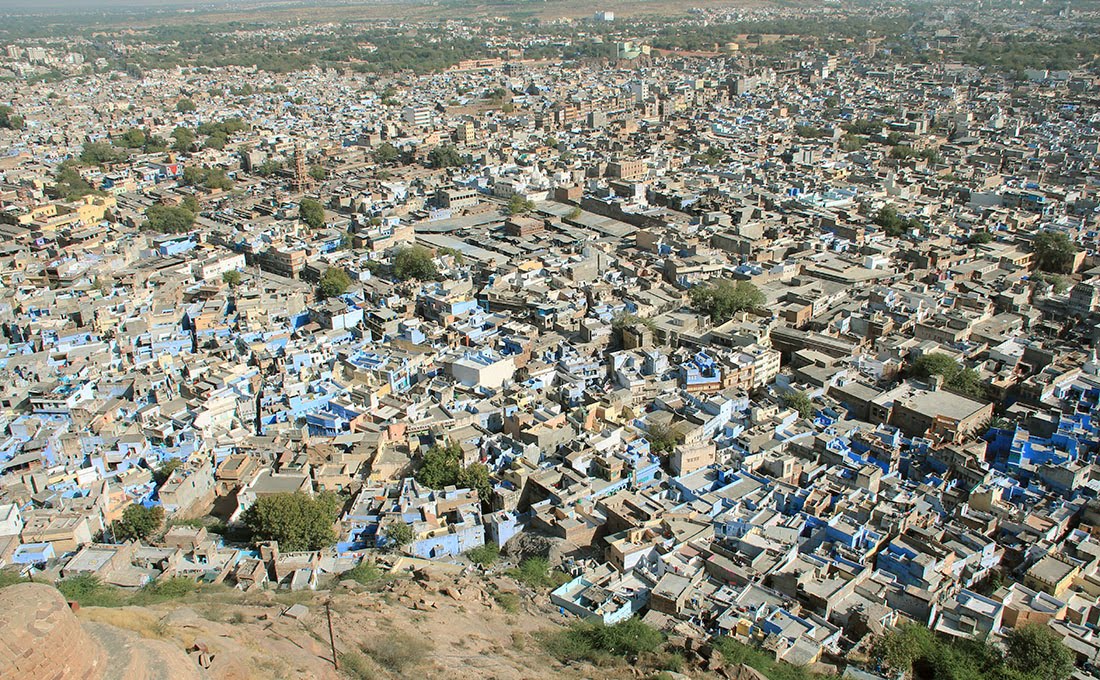

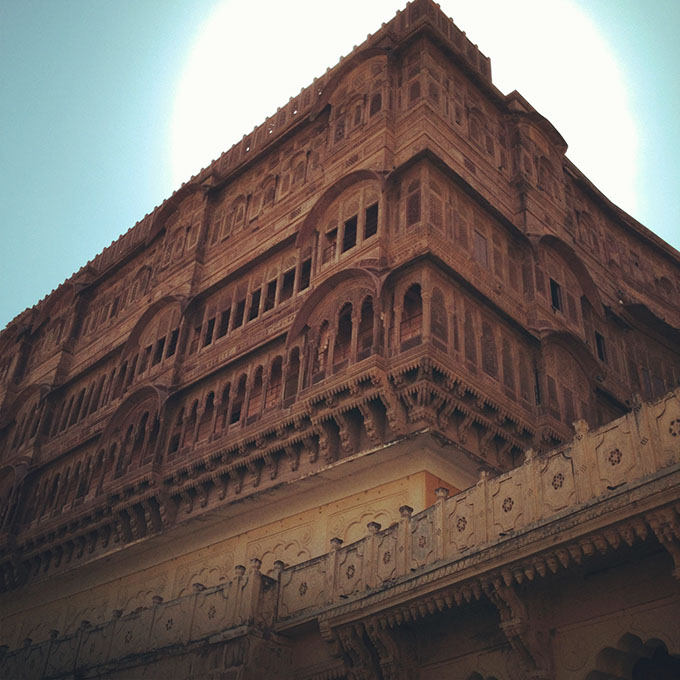

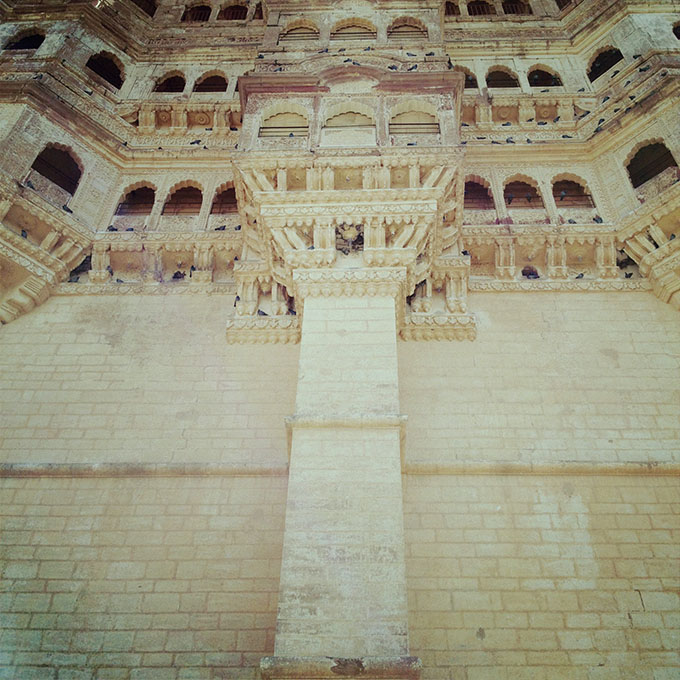

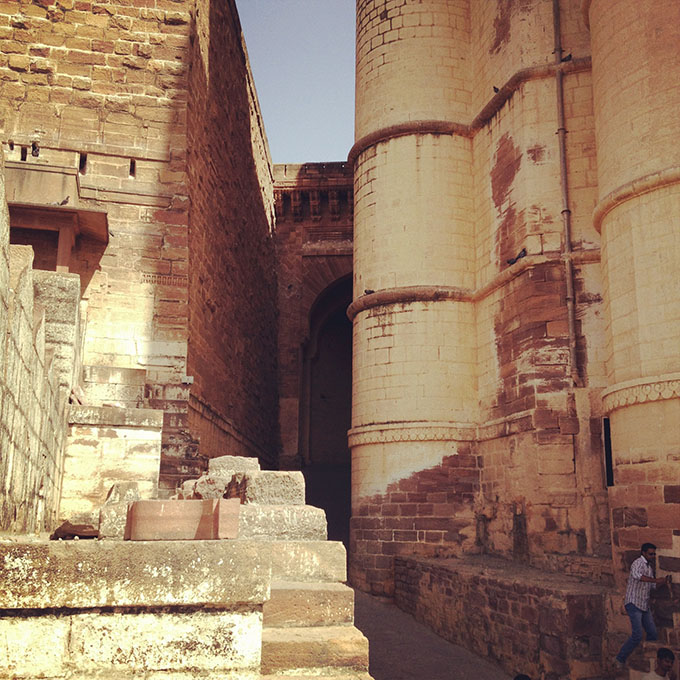

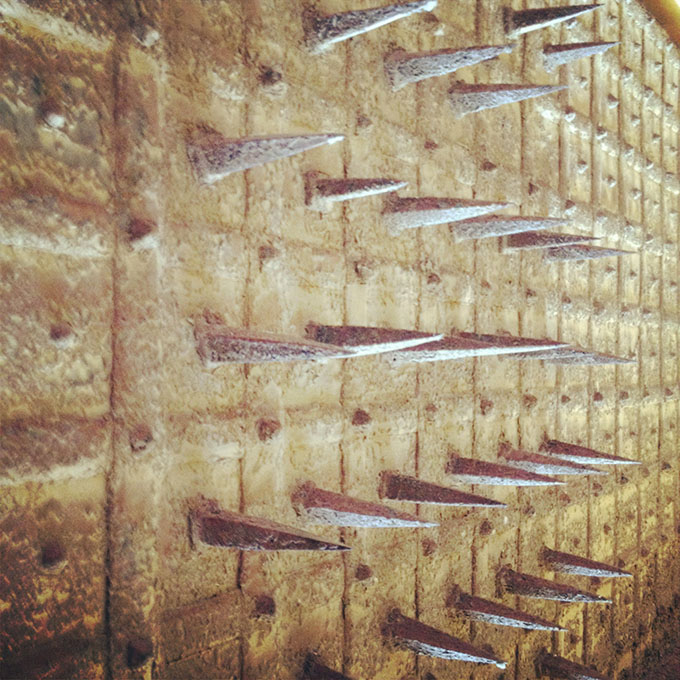

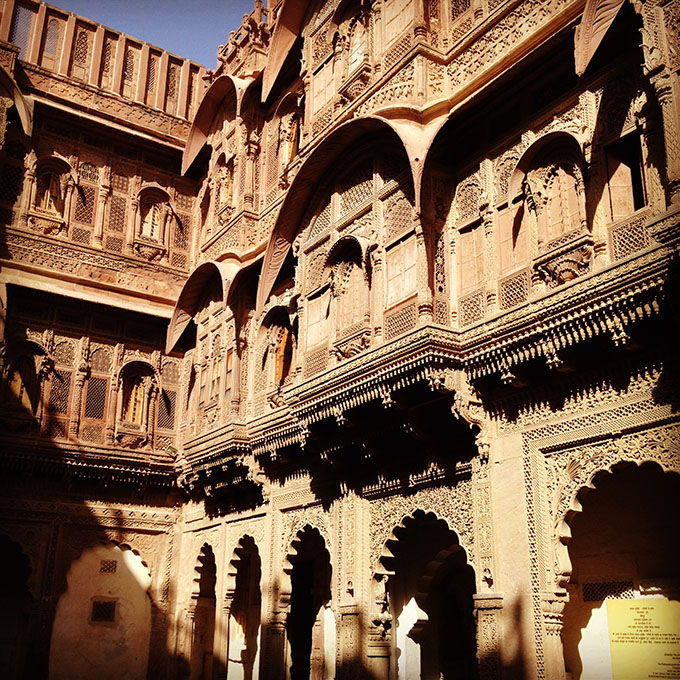

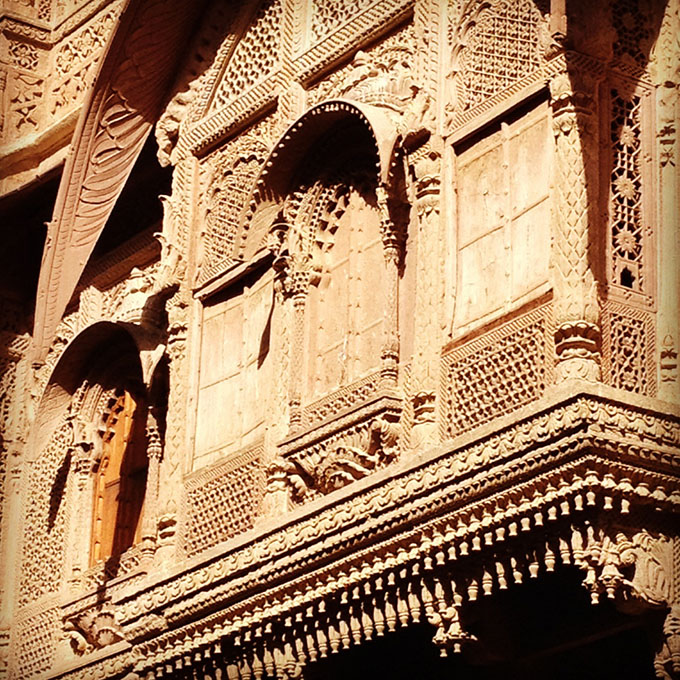

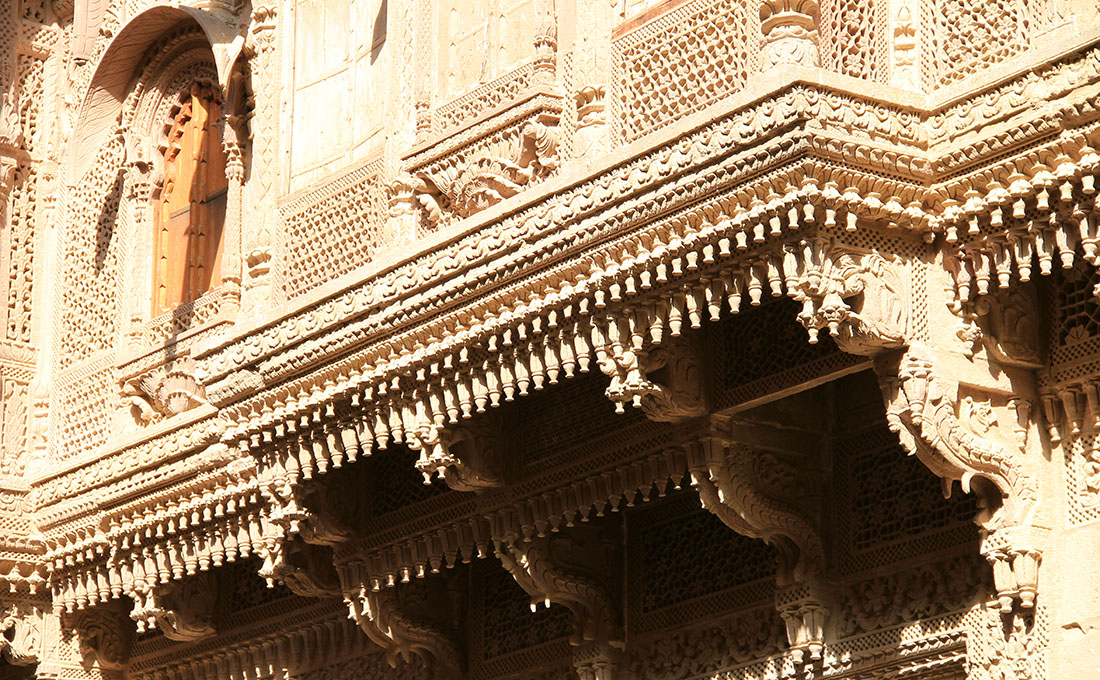

[Images: Overlooking Jodhpur, including the city’s many blue

[Images: Overlooking Jodhpur, including the city’s many blue

[Images: Walking around Jodhpur; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Walking around Jodhpur; photos by BLDGBLOG]. [Image:

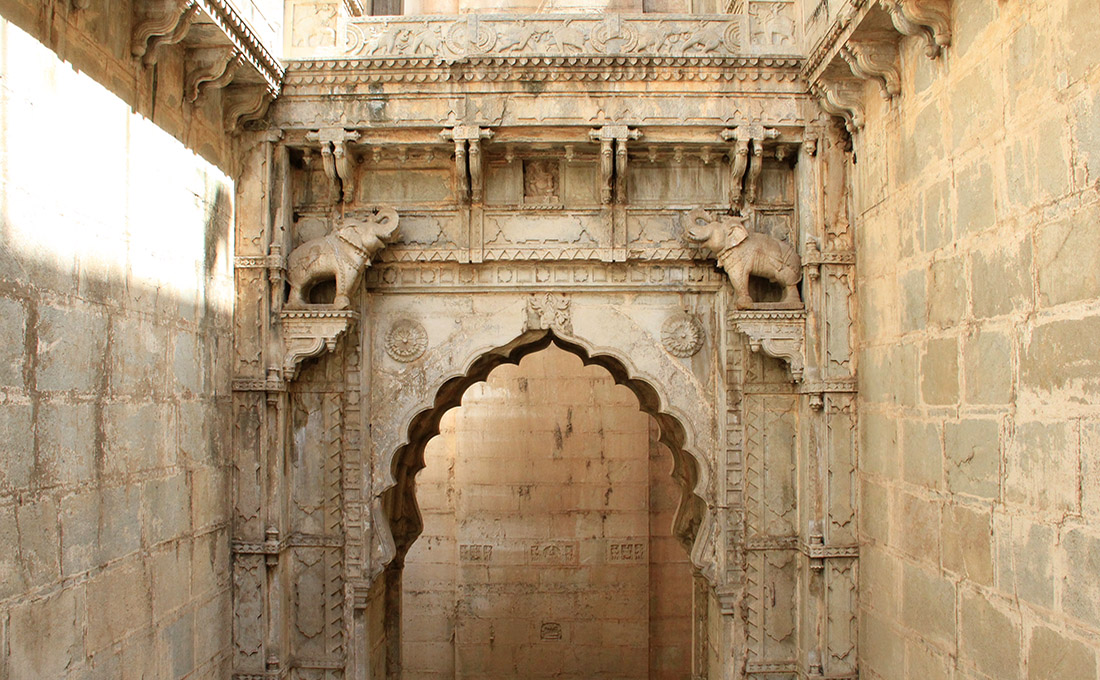

[Image:  [Image: Birds flying over

[Image: Birds flying over  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG]. [Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: The Raniji ki stepwell, Bundi, India; photos by BLDGBLOG].

[Images: Inside the stepwell; bottom photo (by

[Images: Inside the stepwell; bottom photo (by