[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

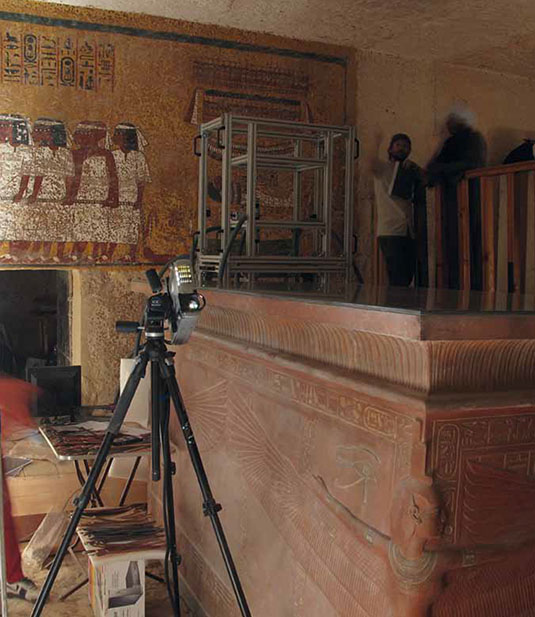

On the 90th anniversary of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, an “authorized facsimile of the burial chamber” has been created, complete “with sarcophagus, sarcophagus lid and the missing fragment from the south wall.”

The resulting duplicate, created with the help of high-res cameras and lasers, is “an exact facsimile of the burial chamber,” one that is now “being sent to Cairo by The Ministry of Tourism of Egypt.”

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

This act of architectural replication-at-a-distance has been described in a fascinating booklet—from which these quotations come—just released by the Factum Foundation as an extreme act of conservation, “a new initiative to safeguard this and other [Egyptian] tombs… through the application of new recording technologies and the creation of exact facsimiles of tombs that are either closed to the public for conservation reasons or are in need of closure to preserve them for future generations.”

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: Laser-scanning King Tut’s tomb, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

Assembling the back-up tomb took place further south, in Luxor, requiring a step-by-step process. Laser-equipped conservationists first had “to digitize the tombs, archive and transform the data and then re-materialize the information in three dimensions at a scale of 1:1.”

[Image: Routing tomb details into polyurethane, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: Routing tomb details into polyurethane, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

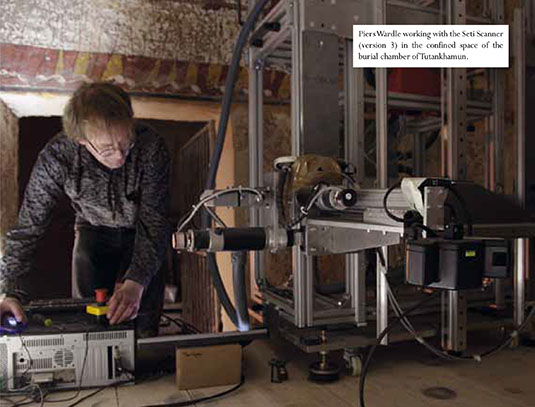

And it’s quite a meticulous process.

The booklet both describes and visually documents the time and attention that went into everything from milling minute details into polyurethane sheets to printing full-color replica wall images onto “a thin flexible ink-jet ground backed with an acrylic gesso and then an elastic acrylic support… built in seven layers [that are then] rolled onto a slightly textured silicon mold” that serves as the artificial tomb walls.

Even that skips the thousands of hours devoted purely to laser-scanning.

[Image: One of the scanning set-ups used to “record” the tombs, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: One of the scanning set-ups used to “record” the tombs, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

Taken all together, this has proven, the Foundation explains, “that it is possible, through the use of digital technology, to record the surfaces and structure of the tombs in astonishing detail and reproduce it physically in three dimensions without significant loss of information.”

Interestingly, we read that this was “done under a licence to the University of Basel,” which implies the very real possibility that unlicensed duplicate rooms might also someday be produced—that is, pirate interiors ripped or printed from the original data set, like building-scale “physibles,” a kind of infringed architecture of object torrents taking shape as inhabitable rooms.

However, equally interesting is something else the project documentation mentions: that every historical monument—every tomb, artifact, or even outdoor space—comes with “specific recording challenges,” and these challenges include things like humidity, temperature, and dust. This, then, further implies that the resulting “exact replicas” could very well include what we would, in other contexts, refer to as render glitches, or simply representational mistakes built into the final product due to flaws of accuracy in the equipment used to produce it.

As such, given enough time, a huge budget, and lots of interns, we could perhaps expect to see a series of these “exact” copies gradually diverge more and more—a detail here, a detail there—from the original reference space, a chain of inexact repetitions and flawed surrogates that eventually come to define their own architecture, with, we can imagine, no recognizable original in sight.

[Image: Printing the facsimile, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

[Image: Printing the facsimile, courtesy of the Factum Foundation].

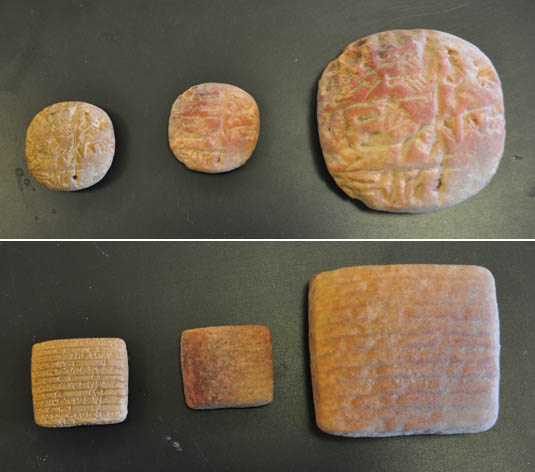

This story of King Tut’s duplicate tomb brings to mind—amongst other things, including multiple complete replicas of the prehistoric cave paintings at Lascaux—a collection of 3D-printed cuneiform texts at the Cornell Creative Machines Lab.

For that project, professors Hod Lipson and David I. Owen “had the idea of implementing 3D scanning and 3D printing technology to create physical replicas of the tablets [using ZCorp powder-based ink-jet printers] that look and feel almost exactly like the originals.”

[Image: 3D-printed replicant cuneiform tablets by Hod Lipson and David Owen at the Cornell Creative Machines Lab].

[Image: 3D-printed replicant cuneiform tablets by Hod Lipson and David Owen at the Cornell Creative Machines Lab].

The idea is that, with the right networks of scanners and printers, as well as curatorial access to museum collections around the world, perhaps we might be able to reproduce, more or less at will, otherwise unique historical objects. We could download ancient stone tools, for instance, print out a quick wall fragment to use in a lecture, or sew together expertly aged carpets and clothes.

Why go to a museum at all, then, when you can simply buy the right printhead?

The nature of how we might encounter historical objects in an era of near-exact 3D recording technologies—that is, that such objects might not be encountered at all, having long ago been replaced by “authorized facsimiles”—returns, in many ways, to an earlier mode of object conservation and inheritance.

In their book Anachronic Renaissance, for instance, Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood write of what they call a long “chain of effective substitutions” or “effective surrogates for lost originals” that nonetheless reached the value and status of an icon in medieval Europe. “[O]ne might know that [these objects] were fabricated in the present or in the recent past,” Nagel and Wood write, “but at the same time value them and use them as if they were very old things.” They call this seeing in “substitutional terms”:

To perceive an artifact in substitutional terms was to understand it as belonging to more than one historical moment simultaneously. The artifact was connected to its unknowable point of origin by an unreconstructible chain of replicas.

These replicas—for example, painted panels, statuettes, and even architectural models—could thus still hold the aura, if you will, of a timeless past, the weight of true history, not simply that of a souvenir, despite being nothing more than references and echoes of what often turned out to be very different originals.

King Tut’s facsimile tomb, meanwhile, is an interesting variation on this idea of substitutional thinking, a decoy spatial antiquity that could very well outlive the place it was meant to help preserve.

Read a bit more over at the Factum Foundation, or download the PDF from which I’ve been quoting.

They were doing it in Victorian times, often on a monumental scale:

http://www.vam.ac.uk/users/node/15151

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/r/cast-courts-room-46a/

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/r/cast-courts-room-46b/