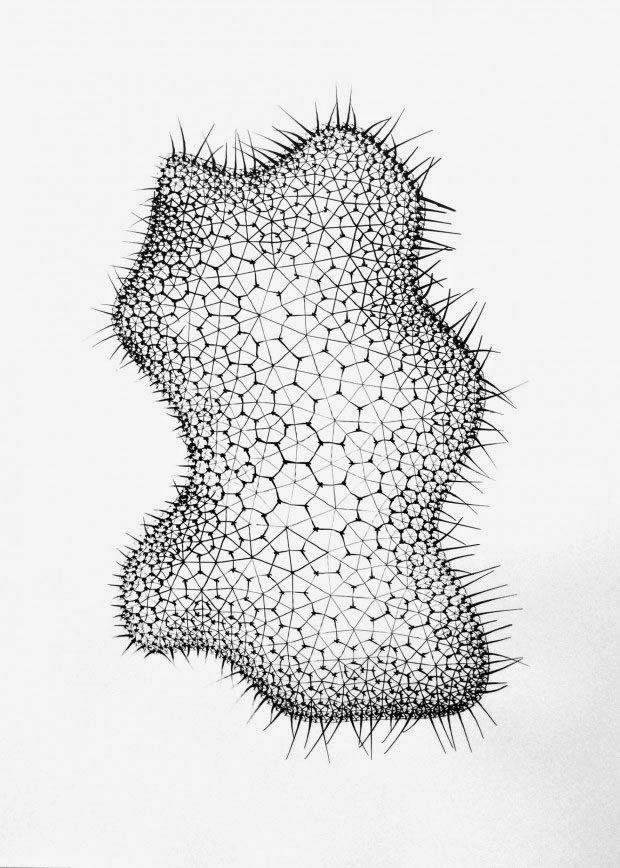

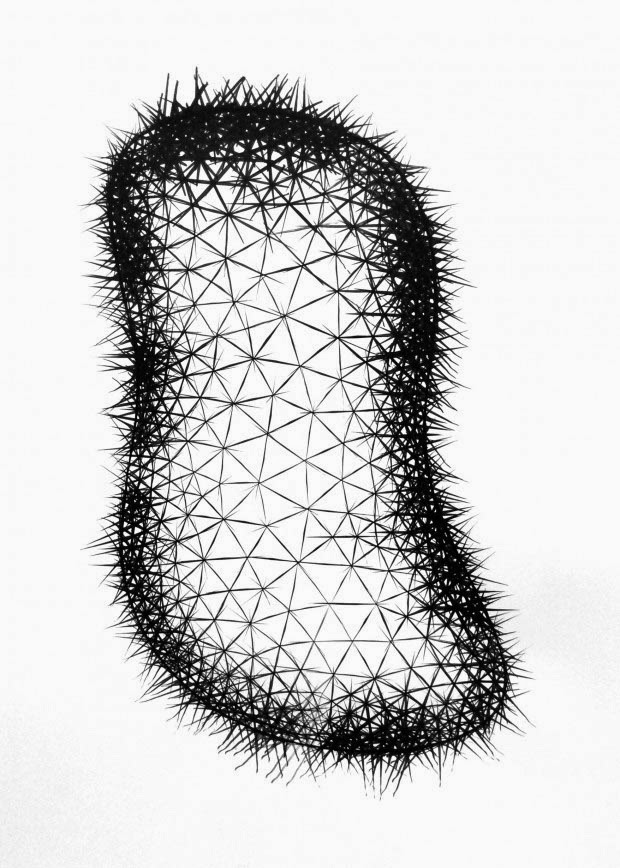

[Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

[Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

A new exhibition opens next week at the Hubbell Street Galleries in San Francisco, part of the California College of the Arts, called Drawing Codes: Experimental Protocols of Architectural Representation. The idea behind the group show is to look at “the relationship between code and drawing” (emphases theirs), or “how rules and constraints inform the ways we document, analyze, represent, and design the built environment.”

Drawing Codes is curated by Andrew Kudless and Adam Marcus, with Clayton Muhleman, and it features work by Erin Besler, Elena Manferdini, Jimenez Lai, the Oyler Wu Collaborative, Rael San Fratello, and many more.

As Kudless—of Matsys fame—pointed out to me over email, the curators “gave all of the participants a set of codes that they had to follow (e.g. all black and white, orthographic projection, 25″ x 25″, etc.),” using this set of constraints to, among other things, foreground differences in approach between each participating architect.

If everyone’s doing the same thing, then how each person does it becomes more revealing.

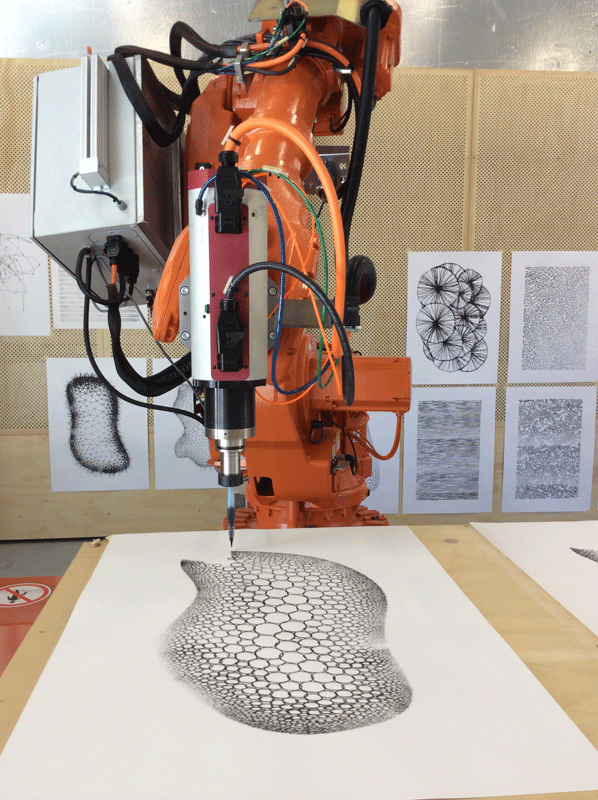

[Image: “Half-Hearted Diamonds” by Jimenez Lai/Bureau Spectacular].

[Image: “Half-Hearted Diamonds” by Jimenez Lai/Bureau Spectacular].

Perhaps ironically, it was actually the drawing by Kudless himself—which I first saw on Instagram—that caught my interest.

Called “The Walled City (10-Mile Version),” that project imagines an entire metropolis that is nothing but one, continuous wall.

Kudless explained that it came about by posing himself a rhetorical question: “What would a city look like if it was a wall and nothing else? I’ve been fascinated with walls that have grown thick enough to be buildings in themselves. From medieval European city walls to the Great Wall in China, there is something really interesting about taking something that is ostensively about separating two territories and turning into an inhabitable space in its own right.”

[Image: Close-up from “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

[Image: Close-up from “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/Matsys].

The results: a rule-constrained exploration of how a wall could become a city.

I started to play around with slowly increasing a wall’s length while preventing it from moving outside a site or intersecting itself. At a certain point in the growth process, the wall takes over the entire site. There is still an inside and outside to the wall, but sometimes the outside is deep inside the site boundary or vice versa. At that point, I was left with a big squiggly wall, but realized that I needed some sort of roofscape to make it read as a city and not just a thick wall. That’s when I turned to Google’s autocomplete feature to give me suggestions on what programs [spatial functions] a rooftop might support. I worked my way from A to Z pretty much accepting whatever suggestion Google’s autocomplete gave me and started designing parametric definitions that could implement that program on a number of different sites along the wall’s top.

The various social and architectural functions distributed around the massive roofscape included, for example, Rooftop Antenna, Rooftop Bar, Rooftop Cafe, Rooftop Deck, Rooftop Exhaust, Rooftop Film, Rooftop Garden, Rooftop Hotel Pool, and so on.

Interestingly, Kudless also pointed out that, if he were to run the same generative script again, it would likely produce “a similar, but not identical city,” and it would almost certainly not result in a wall exactly ten miles in length (which, in this case, was purely a coincidence, he explained).

In any case, I’ve been impressed by Kudless’s work for a long time; check out these older posts on his projects Nevada Sietch and robotic drawing protocols, for example, and then stop by the exhibition when it opens next week. There will be a reception on January 19 at 5:30pm at 161 Hubbell Street. More info.

[Image: “Design for the Water Clock of the Peacocks,” from the Kitab fi ma’rifat al-hiyal al-handasiyya (Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices) by Badi’ al-Zaman b. al Razzaz al-Jazari, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art].

[Image: “Design for the Water Clock of the Peacocks,” from the Kitab fi ma’rifat al-hiyal al-handasiyya (Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices) by Badi’ al-Zaman b. al Razzaz al-Jazari, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art]. [Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/

[Image: “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/ [Image: “Half-Hearted Diamonds” by Jimenez Lai/

[Image: “Half-Hearted Diamonds” by Jimenez Lai/ [Image: Close-up from “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/

[Image: Close-up from “The Walled City (10-Mile Version)” by Andrew Kudless/ [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

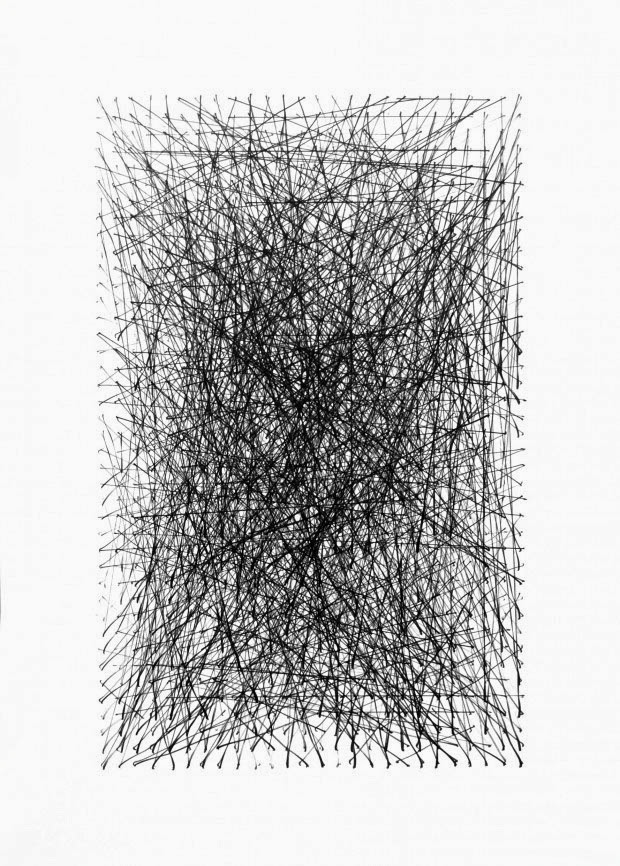

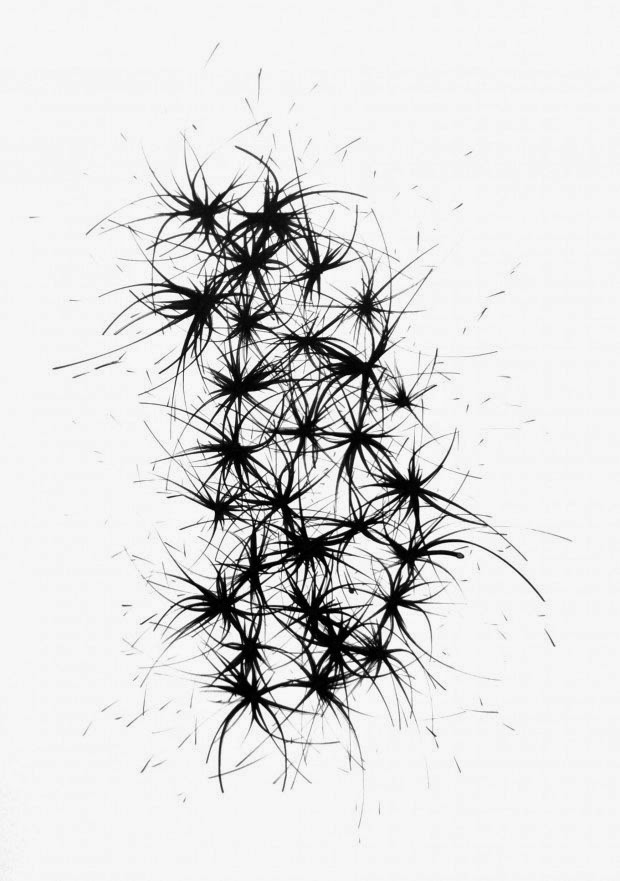

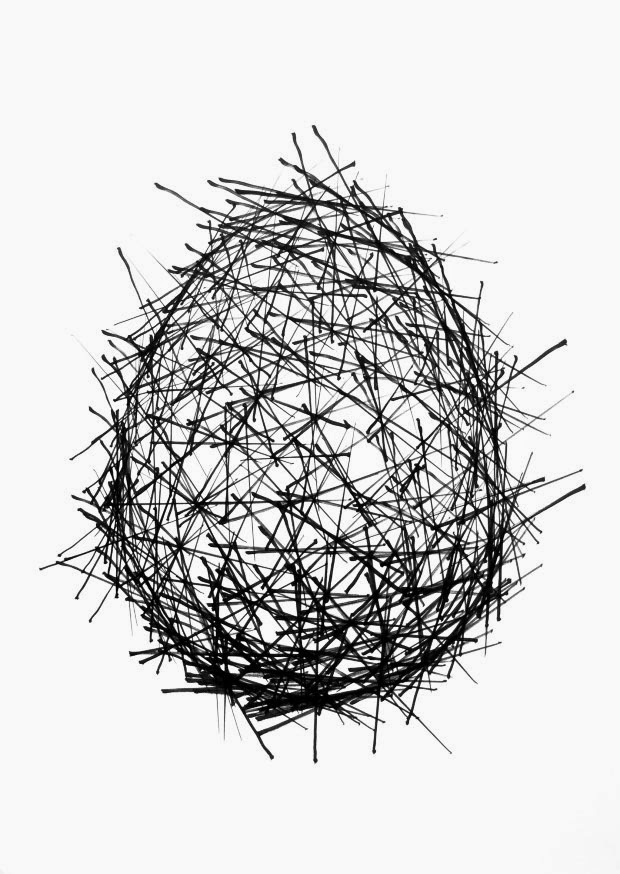

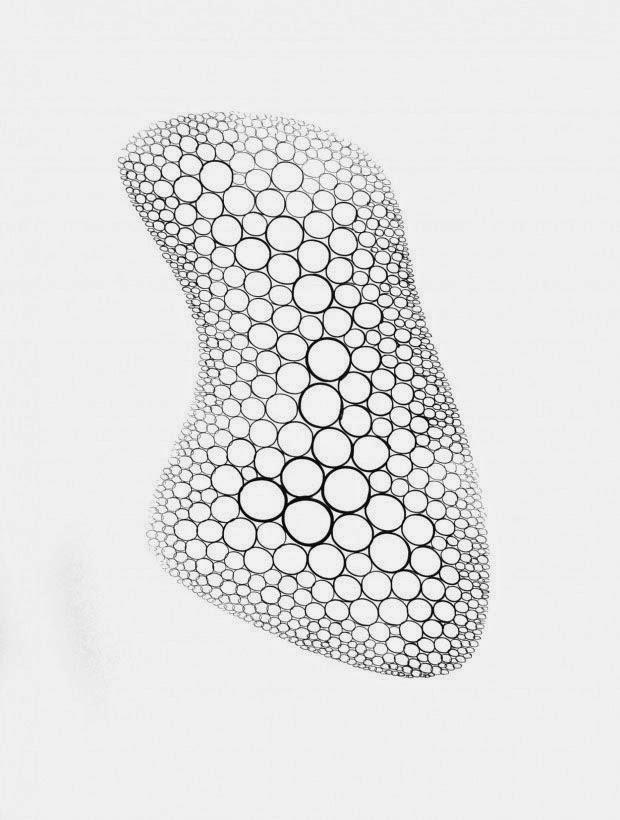

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “

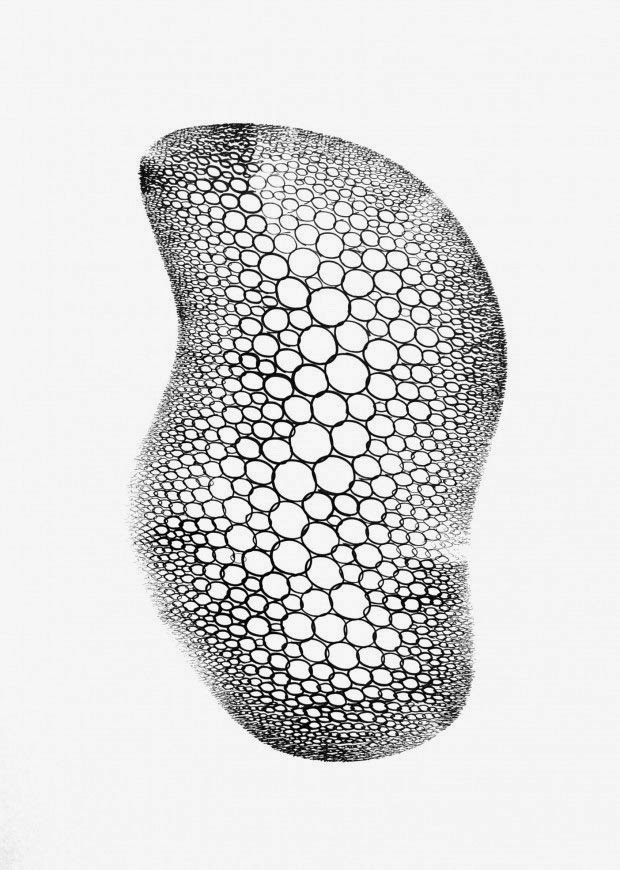

[Image: “Untitled #13,” from “ [Image: The robot at work, from “

[Image: The robot at work, from “ [Image: “Untitled #16,” from “

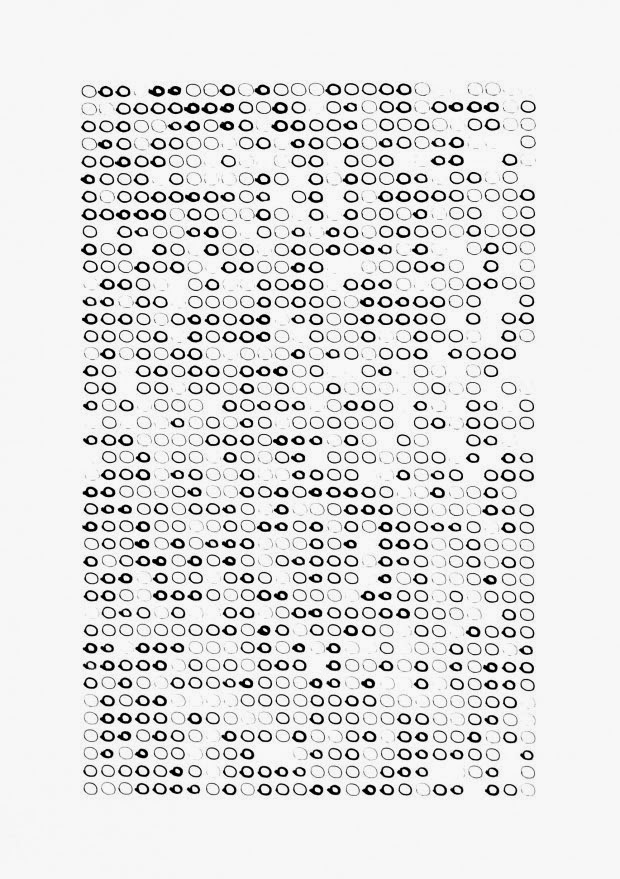

[Image: “Untitled #16,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “

[Image: “Untitled #6 (1066 Circles each Drawn at Different Pressures at 50mm/s),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “

[Image: “Untitled #7 (1066 Lines Drawn between Random Points in a Grid),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “

[Image: “Untitled #15 (Twenty Seven Nodes with Arcs Emerging from Each),” from “ [Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “

[Image: “Untitled #3 (Extended Lines Drawn from 300 Points on an Ovoid to 3 Closest Neigh[bor]ing Points at 100mm/s)” (2014) from “ [Image: “Untitled #12,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #12,” from “ [Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

[Image: “Untitled #14,” from “

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called  [Image: The

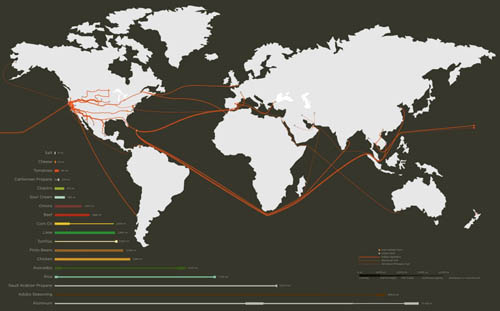

[Image: The  Like a culinary version of

Like a culinary version of  [Image: “There are two basic types of taco trucks,” we read; “the first and most common is the transient truck which is a truck that stops at approximately 20 different locations at 20-minute intervals during an 8-hour shift, typically beginning at 6am and ending at 2pm. The second type is the semi-permanent truck, which is a truck that has found a location that has a density of clientele to sustain it for an extended period of the day, creating a nearly fixed presence in a particular community.” From

[Image: “There are two basic types of taco trucks,” we read; “the first and most common is the transient truck which is a truck that stops at approximately 20 different locations at 20-minute intervals during an 8-hour shift, typically beginning at 6am and ending at 2pm. The second type is the semi-permanent truck, which is a truck that has found a location that has a density of clientele to sustain it for an extended period of the day, creating a nearly fixed presence in a particular community.” From